Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Beginnings

- 2 Modernist Experiments: Gertrude Stein and Others

- 3 H.D. and the Limits of Vision

- 4 Ernest Hemingway: The Observer's Visual Field

- 5 Success and Stardom in F. Scott Fitzgerald

- 6 William Faulkner: Perspective Experiments

- 7 John Dos Passos and the Art of Montage

- 8 Dreiser, Eisenstein and Upton Sinclair

- 9 Documentary of the 1930s

- 10 John Steinbeck: Extensions of Documentary

- 11 Taking Possession of the Images: African American Writers and the Cinema

- 12 Into the Night Life: Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin

- 13 Nathanael West and the Hollywood Novel

- Bibliography

- Index

11 - Taking Possession of the Images: African American Writers and the Cinema

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Beginnings

- 2 Modernist Experiments: Gertrude Stein and Others

- 3 H.D. and the Limits of Vision

- 4 Ernest Hemingway: The Observer's Visual Field

- 5 Success and Stardom in F. Scott Fitzgerald

- 6 William Faulkner: Perspective Experiments

- 7 John Dos Passos and the Art of Montage

- 8 Dreiser, Eisenstein and Upton Sinclair

- 9 Documentary of the 1930s

- 10 John Steinbeck: Extensions of Documentary

- 11 Taking Possession of the Images: African American Writers and the Cinema

- 12 Into the Night Life: Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin

- 13 Nathanael West and the Hollywood Novel

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

The Birth of a Nation and Beyond

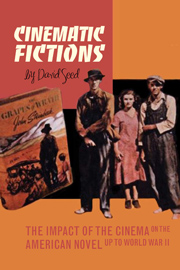

During his campaign for the governorship of California in 1934 Upton Sinclair was partly defeated by bogus newsreels showing unkempt migrants heading for that state. He was, in other words, defeated by images over which he had no control. And when the migrants in The Grapes of Wrath are called ‘Okies’ they are being framed by an abusive label, which Steinbeck's visual techniques are designed to counter. African American writers at the beginning of the twentieth century were even more severely disadvantaged by the fact that they were operating within a culture in which they were already colonized by hostile stereotypes. Their self-images were not their own, nor did their situation improve with the coming of the cinema. Thomas Cripps has shown in his 1977 study Slow Fade to Black that, after a brief period of relatively free imaging in early films, from the mid-1910s into the twenties the cinema ‘continued to draw on old Southern stereotypes of Negroes as happy, lazy workers on the plantation’. This situation lasted at least up to the Second World War. As late as 1943, answering his question ‘Is Hollywood Fair to Negroes?’, Langston Hughes declared: ‘for a generation now, the Negro has been maligned, caricatured, and lied about on the American screen, and pictured to the whole world […] as being nothing more than a funny-looking, dull-witted but comic servant’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Cinematic FictionsThe Impact of the Cinema on the American Novel up to World War II, pp. 212 - 233Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2009