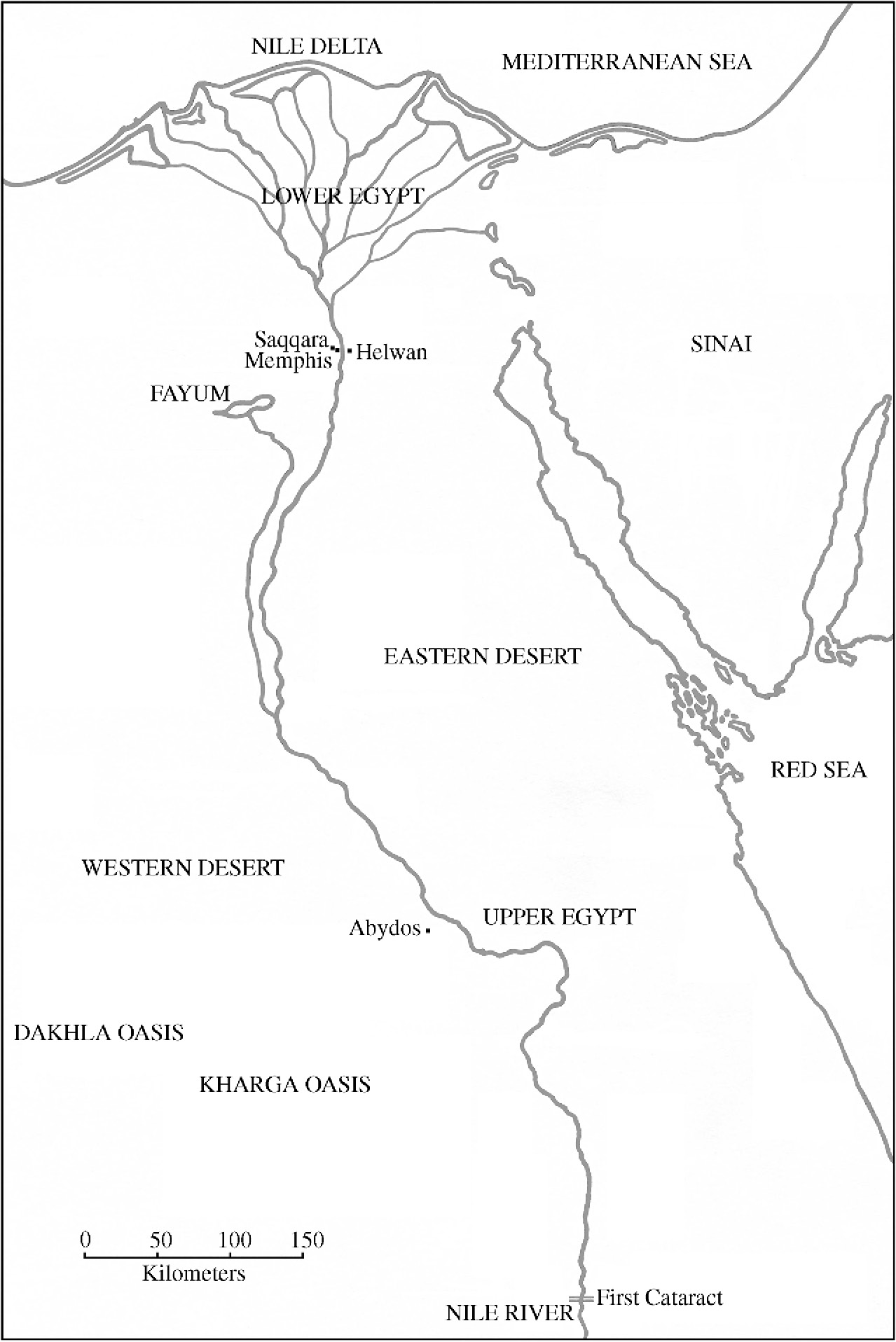

The Early Dynastic Period consists of the First and Second Dynasties (c. 3000–2686 BCE). These dynasties ruled over Egypt from a royal court at the city of Memphis, but the kings of the First Dynasty continued to build tombs at their ancestral cemetery at Abydos in Upper Egypt, while those of the Second Dynasty alternated between Saqqara to the west of the Memphis, and Abydos. Nonetheless, many of the officials of the First- and Second-Dynasty kings built their tombs at Saqqara to the west of Memphis or at Helwan to the east of it. (See Map 1.1 and Table 1.1.)

Map 1.1. Egypt in the Early Dynastic Period

Table 1.1. The Early Dynastic Period

| Protodynastic Period (c. 3200–3000 BCE) |

| Owner of Tomb U-j |

| Iry-hor |

| Early Dynastic Period (c. 3000–2686 BCE) |

| Dynasty 1 (c. 3000–2890 BCE) |

| Narmer |

| Aha |

| Djer |

| Djet |

| Den |

| Queen Merneit |

| Anedjib |

| Semerkhet |

| Qaa |

| Dynasty 2 (c. 2890–2686 BCE) |

| Hetepsekhemwy |

| Raneb |

| Ninetjer |

| Weneg |

| Sened |

| Sekhemib-Peribsen |

| Khasekhemwy |

The Early Dynastic Period witnessed the first relatively limited use of writing in Egypt. Short monumental inscriptions on stone stelae labeled the tombs of kings and courtiers; short inscriptions on ivory, bone, stone, and wooden tags labeled some objects in the tombs of kings and officials; short commemorative inscriptions appeared on some objects found in tombs and shrines at various sites; and names written inside a royal serekh were incised on pottery and stone vessels. Secondary evidence for writing consisted of impressions of inscribed cylinder seals left on clay used to seal various containers in the tombs of kings and officials, which did not require literacy on the part of the users.1

Documentation and Enforcement

There is little inscribed evidence concerning judicial administration in the Early Dynastic Period. The title of vizier, the highest official under the king and the head of the central judicial administration in the Old Kingdom, may appear already in the Early Dynastic Period, but it is not securely attested until the Third Dynasty.2 There is some evidence that the state made use of writing to document and enforce community tax obligations to the state, through surveys and censuses of objects of taxation. The limited use of writing, however, probably prevented it from being used more widely to document and enforce individual tax obligations or private transactions, for example.

Field Surveys and Censuses: Some evidence for surveys and censuses for tax purposes in the Early Dynastic Period comes from several fragments of royal annals. These royal annals record the names of successive years, which consisted of one or two significant events in each year. The annals were inscribed in the Fifth Dynasty at the earliest, but the year names were probably assigned in the Early Dynastic Period, because there are wooden and ivory tags and labels from the tombs of First Dynasty kings and officials at Abydos and Saqqara, respectively, that contain similar year names, suggesting that the royal annals accurately preserved older records.3 In the best preserved fragment of royal annals known as the Palermo Stone, every second year entry in the fourth row on the recto is identified by a combination of two events: the Following of Horus (šms Ḥr), which was probably a religious ceremony or a royal procession through the country, and the fourth through tenth occasions of the count (zp X ṯnwt).4 These entries are clearly labeled as belonging to King Ninetjer of the Second Dynasty. The term “count” in isolation is ambiguous, but every second year entry in the beginning of the fifth row on the recto of the Palermo Stone refers to a combination of the following of Horus and the sixth through eighth occasions of the count of gold and fields (zp X ṯnwt nbw sḫt).5 These entries are not labeled but must belong to the king preceding Djoser, who should be either Khasekhemwy of the Second Dynasty or Nebka of the Third Dynasty if he precedes rather than follows Djoser. The qualification “of gold and fields” argues that these counts were fiscal. The count of gold could represent an inventory of existing wealth, but the count of fields probably represented a survey of income sources, from which revenue was collected at the harvest.

In the Second Dynasty, the occasion of the count is closely associated with the Following of Horus, but the Following of Horus is already attested in the First Dynasty. It appears without an accompanying occasion of the count already in every second year entry in the second row on the recto of the Palermo Stone, which is unlabeled but is often attributed to King Djer of the First Dynasty. Neither the Following of Horus nor the occasion of the count appears in the third row on the recto, which is also unlabeled and is often attributed to King Den of the First Dynasty. Some have suggested that the Following of Horus already included an inventory for tax purposes in the First Dynasty,6 although if that were true it would hardly have been necessary to refer to the inventory separately as “the occasion of the count” alongside the Following of Horus in the Second Dynasty. Others argue that an inventory did not accompany the biennial Following of Horus until the Second Dynasty, when the count is explicitly mentioned alongside it on the Palermo Stone.7 Wilkinson suggests that a census or survey may have grown out of the Following of Horus, since a ceremonial progress through the country would have been a good opportunity to assess its wealth,8 but the limited use of writing in the Early Dynastic Period argues against countrywide censuses or surveys of individual people, fields, or other properties for tax purposes. Indeed, there is no evidence of registration of individual people or properties for tax purposes even in the following Old Kingdom, when there is far more extensive use of writing, only of estates (ḥwwt) and towns (niwwt) that were collectively responsible for taxes.

Estates: In the reign of Djer in the First Dynasty, clay container sealings and a few tags, labels, and vessel inscriptions from tombs of kings and officials at Abydos and Saqqara begin to bear the names of districts, whose determinatives categorize them as estates (ḥwwt). These names probably indicated the sources of the contents of the containers and vessels and the objects formerly associated with the tags.9 Estates (ḥwwt) are well known from the following Old Kingdom, when they frequently appear along with towns (niwwt) in lists in royal and private funerary chapels, often personified as offering bearers in tomb scenes. The funerary attestations suggest that revenues from specific estates and towns were assigned to specific royal and private funerary cults.10 Estates predominated in the early Old Kingdom, while towns became more common in the late Old Kingdom, suggesting a trend away from estates toward towns.11 Inscriptions and scenes from late Old Kingdom tomb-chapels reveal that estates and towns were both managed by relatively low-ranking chiefs (ḥḳꜣw), who were beaten for nonpayment of taxes.12 Estates and towns were also the basis for unit formation in military service, which was a form of compulsory labor.13 Estates and towns thus appear to have been collectively responsible for payment of harvest taxes and compulsory labor, and their representatives were held personally responsible for nonpayment.

Distribution

Grave goods in tombs provide archaeological evidence that forms of distribution took place in Egypt for centuries before the appearance of writing shortly before the Early Dynastic Period. Nonetheless, the size and wealth of tombs of kings and officials started growing rapidly around the time that writing appeared, indicating that the systems of distribution were also developing and expanding in this period. The appearance and increasing complexity of written distribution records on grave goods in the Early Dynastic Period thus may track the development of these distribution systems, as well as the development of new applications for writing. These distribution records on labels and sealings attached to offering containers in tombs, and sometimes on the containers themselves, may preserve the names of the districts and institutions responsible for producing and distributing the offering goods. Texts do not seem to refer private transactions in this period, however. This is a logical consequence of the restricted use of writing in this period, which only later in the Old Kingdom spread beyond the royal court and its agents.

Tomb U-j: The earliest written records of distribution known from Egypt come from elite Tomb U-j at Abydos, which dates one or two centuries before the First Dynasty and which may have belonged to an anonymous chief or king of a proto-state centered on Abydos.14 The tomb contained vessels inscribed with names written inside royal serekhs, possibly indicating the institutions responsible for the vessels;15 impressions of nontextual cylinder seals in the clay used to seal vessels, possibly identifying the individuals responsible for the contents of the vessels;16 and ivory, bone, and stone tags that were once attached to other now vanished grave goods, and that were incised with numbers or possible place names, perhaps indicating the origins of the goods.17

Tax-Marks and Other Inscriptions: From the reign of Iry-hor just before the First Dynasty to the reign of Den in the First Dynasty, some incised vessels, clay seal impressions, and incised tags and labels found in royal and private tombs bear inscriptions that have been called tax-marks. The tax-marks identify a type and quality of a product, most often oil, and describe it as received (iw.t), counted (ipw.t), brought (inw), delivered (nḥb, ḏḥꜣ), or food (ḏfꜣ) from either Upper Egypt (Šmꜥw) or Lower Egypt (Mḥw). Tax-marks on tags and labels sometimes also include a year name with the names of the king and of an official. Other inscriptions from this period, however, simply give the name of the king and of an official.18

Royal Domains: In the reign of Djer in the First Dynasty, some jar sealings from royal and private tombs begin to name estates (ḥwwt), discussed previously, and institutions whose names were written inside a hieroglyph resembling a fortified wall.19 The reading of the hieroglyph is uncertain, so these institutions have been called royal domains.20 They should not be confused with the estates and later towns that have also been called domains.21 Indeed, the royal domains may have received their revenues from estates and other sources, and may have been the institutional ancestors of the later royal mortuary temples.22 In the reign of Den in the First Dynasty, sealings also start to give the names and titles of the officials who managed the royal domains, usually an administrator (ꜥḏ-mr) or controller (ḫrp) or executive (ḥry-wḏꜣ), each coupled with the name of the domain.23

Royal Palaces: In the reign of Djet in the First Dynasty, sealings and other inscriptions begin to attest to an institution known as the royal house (pr-nzwt) alongside the royal treasury (pr-ḥḏ/pr-dšr). It was probably responsible for supporting the king and his court at various palaces, analogous to the Residence in the Old Kingdom. A controller of the royal house (ḫrp pr-nzwt) is attested.24

Royal Treasuries: In the reign of Den in the First Dynasty, some sealings and other inscriptions from the tombs of kings and officials begin to refer to royal treasuries.25 Tax-marks disappear at this time, but references to estates and domains continue, indicating that they were separate though possibly subordinate institutions. The royal treasuries were alternately named the white house (pr-ḥḏ) or the red house (pr-dšr). From the reign of Den it was known as the white house, and then from the reign of Anedjib through that of Ninetjer as the red house. It was renamed the white house again under Sekhemib-Peribsen, and the red house again under Khasekhemwy, until it finally became known as the double white house (pr.wy-ḥḏ) or double treasury in the Old Kingdom. It would be tempting to see the white and red houses as the component elements of the double treasury, perhaps representing Upper and Lower Egypt, except that they are never attested together in the same place or even the same reign.26 In the Second Dynasty, the treasury appears to have contained a number of subdepartments. These included a workshop (pr-šnꜥ), a house of redistribution (pr-ḥry-wḏb), and a provisioning department (iz-ḏfꜣ).27 Royal seal-bearers or chancellors (ḫtmw-bity) may have managed the treasury and were probably the highest-ranking officials in the central administration below the king and the vizier, though the vizier is not securely attested until the Old Kingdom. An executive of the house of redistribution (ḥry-wḏꜣ pr-ḥry-wḏb) is attested in the Second Dynasty, as is a scribe of the provisioning department (zẖ iz-ḏfꜣ).28

Entrepreneurial Activities

In addition to simply redistributing goods and services, the state sometimes used them to facilitate the future acquisition of raw materials or production of goods. This usually took the form either of expeditions beyond the populated areas under the control of the Egyptian state for warfare and booty, trade or mining, or of the foundation of institutions within the populated areas of Egypt.

Expeditions: The fragment of royal annals known as the Palermo Stone contains year names apparently commemorating military expeditions, such as “smiting the bowmen,” in what is probably the reign of Den in the First Dynasty, and destroying two places called Shem-Re and Ha in the reign of Ninetjer in the Second Dynasty.29 Wooden and ivory tags and labels from the tombs of First Dynasty kings and officials at Abydos and Saqqara also preserve year names apparently commemorating military expeditions. A label of King Den reads “first occasion of smiting the easterners.”30

Foundations: The Palermo Stone also contains year names that commemorate the creation of statues, boats, and buildings, some of which may reflect the foundation of institutions if they were endowed with revenues. In the second row in what is probably the reign of Djer in the First Dynasty, there are references to planning (ḥꜣ) the building “Companion of the Gods” (smn-nṯrw) and creating (ms.t, literally giving birth to) images of the gods Iat, Min, and Anubis.31 In the third row in what is probably the reign of Den in the First Dynasty, there are references to planning (ḥꜣ) pools (šw) in the northwest, planning (ḥꜣ) the building “Thrones of the Gods” (sw.t-nṯrw) as well as stretching the cord for its great door (pḏ-šs ꜥꜣ wr) and opening its pool (wp.t-š) in three successive years, and creating (ms.t) images of the gods Sed, Seshat, and Mafdet.32 In the fourth row that is labeled the reign of Ninetjer in the Second Dynasty, there is a reference to stretching the cord (pḏ-šs) for the building “Door of Horus” (r-n-Ḥr), and in the fifth row in what is probably the reign of Khasekhemwy in the Second Dynasty, there are references to building in stone (ḳd inr) the building “the Goddess endures” (nṯrt mn), creating (ms.t) the statue “High is Khasekhemwy” (ḳꜥ Ḫꜥ-sḫm.wy), and “cutting the desert” (šd dšrt) in Duadjefa, which may refer to building a ship as it does in the reign of King Sneferu on the same annal fragment.33

Conclusions

In the Early Dynastic Period, very little is known about the state judicial administration or how written documentation affected enforcement. The state introduced the use of writing to document collection and redistribution of state revenues, presumably because the increased efficiency of extraction offset the costs of training and supporting the necessary scribes. Even so, the state probably only documented collective tax obligations. The limited use of writing, however, probably prevented it from being used more widely. The state does not appear to have used writing to document private property transfers. Such transactions were probably documented orally with local witnesses.