Everyone in the world belongs to at least two families: The one in to which we were born and the ones we create in adulthood. Underlying this shared global experience is a wealth of individual diversity in how family shapes us emotionally, physically, and economically throughout our lives and, in turn, the lives of our children. The first goal of this chapter is to present a holistic conceptual frame for comparing the group inequalities in inputs, family processes, and outcomes discussed in the other chapters of this volume. Crucially, the frame highlights that relative group differences over time and across countries are configured at the intersections of family, market, and state institutions.

Much research in this area, including some of the chapters in this volume, implicitly or explicitly view recent family changes as examples of the “pathology of matriarchy” first raised in Moynihan’s Reference Moynihan1965 report on The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. The basis of this perspective is the strong and persistent correlation between female-headed families and negative outcomes for children (McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013). The point to stress, though, is that these ill effects are particularly acute in the United States with its unique ideological acceptance of large class, gender, racial, and other group inequalities. As revealed in this and other chapters in the volume, the magnitude of the family changes and especially their negative outcomes varies across cultural, economic, and political contexts.

The second goal of this chapter is to argue that the pattern of this cross-context variation does not point to an inherent pathology of matriarchy. Indeed, the differences in life chances across family types are minimized where institutional arrangements, unlike in the United States, support greater gender along with class equality (Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado 2018). Furthermore, gendered responses to the interrelated institutional changes over the past half-century suggest instead it is the pathology of patriarchy disproportionately hurting the life chances of boys and men. I draw broadly on Connell (Reference Connell1987; Connell and Messerschmidt Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005) to define patriarchy as men’s historically institutionalized dominance over women in the family, labor market, and state.Footnote 2 As the institutional support for patriarchy gives way, a sizeable minority of men struggle to adapt in healthy ways, undermining family formation and stability.

Next I outline the conceptual frame for situating family processes and outcomes in their institutional contexts. Then I use the existing literature and other chapters in this volume to highlight how structural changes over the past half-century make patriarchal assumptions untenable for a growing proportion of men. In conclusion, I argue that only fully institutionalizing gender equality will minimize negative outcomes associated with family change. In part, fully-institutionalized gender equality ensures children have access to more economic and emotional resources regardless of family form. More importantly, fully institutionalized gender equality encourages development of new normative masculinities that support greater family stability in evolving institutional contexts.

Dynamic Institutional Intersections

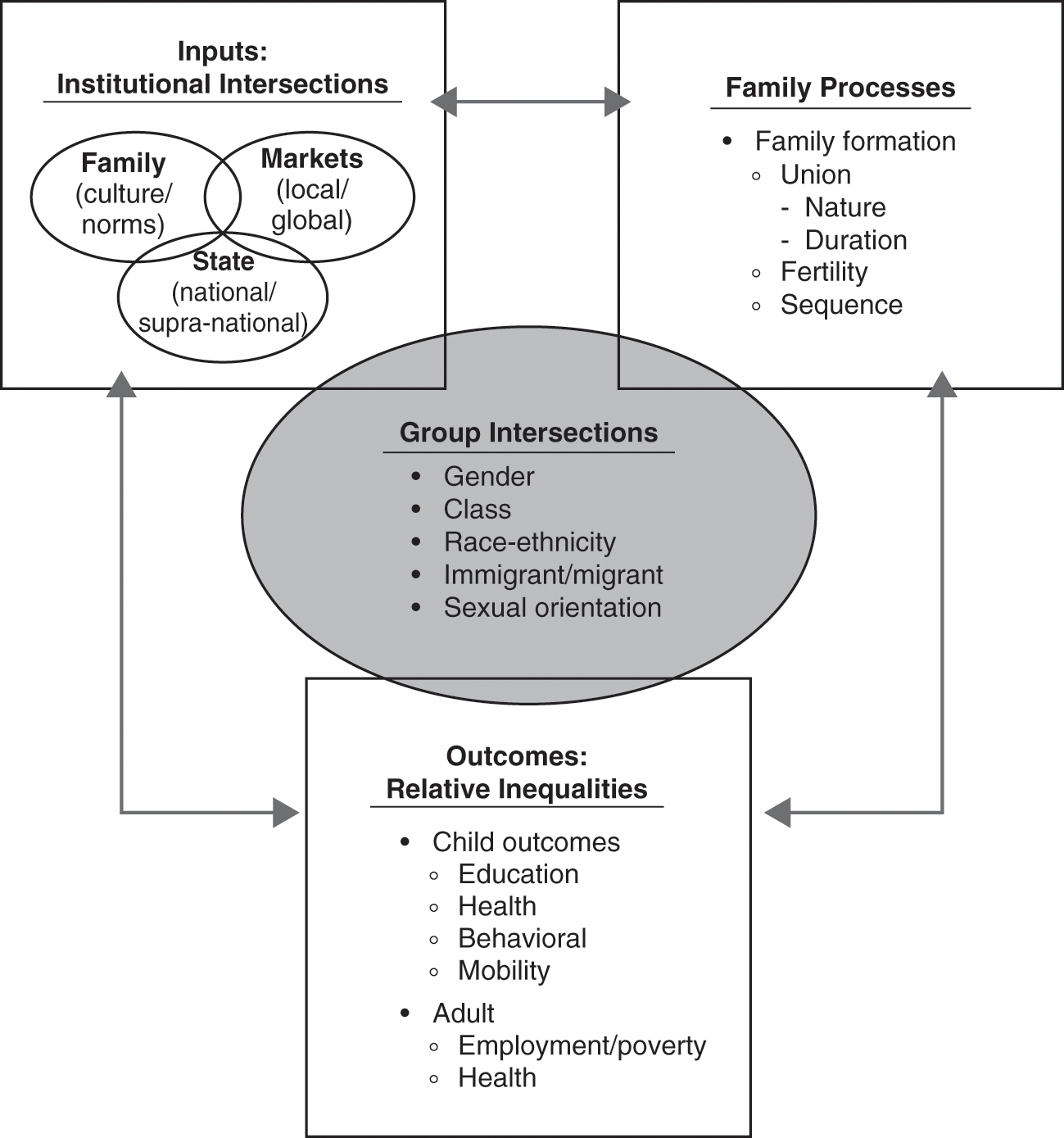

Figure 11.1 diagrams the “nested intersections” of institutions, family processes, and child and adult outcomes. The first box in the diagram indicates the socioeconomic structures that affect family formation and dissolution noted in the second box, which create the group differences in inequalities in individual outcomes outlined in the lower box. The structural effects occur at the intersections of family, market, and state institutions in a dynamic interplay that varies across and within national contexts over time.

Figure 11.1 Nested intersections of institutions, family processes, and outcomes

Intersectionality is not commonly used to refer to institutional effects. Conventionally, intersectionality is a feminist paradigm emphasizing that no single master social category such as gender or class depicts the different experiences and social locations of all group members (McCall Reference McCall2005). Consequently, intersectionality demands that we consider identities and experiences at the intersection of an individual’s group memberships (Collins Reference Collins2002; McCall Reference McCall2005). Hence, Figure 11.1 includes a shaded circle spanning institutions, family processes, and outcomes to indicate that effects vary at the intersection of an individual’s gender, class, race–ethnicity, immigrant status, sexual orientation, and the like. Due to space constraints, discussion in this chapter is primarily limited to gender and class differences, with education used as the main proxy for class.

Similarly, no master institution accounts for institutional effects on people’s lives. Instead, individual and group differences are nested in the intersections of family, market, and state institutions, and supra-national institutions such as the European Union and World Bank. This may seem like common sense, but bears emphasizing when comparing possible causes and consequences of family inequalities across Europe and the Americas as done in this volume. For example, the institution of family includes norms about what or who constitutes a family, along with the expected behavior of family members. During early industrialization, the patriarchal heterosexual, nuclear, male breadwinner/female carer model of family became hegemonic in many, but not all Western economies.

Men’s economic dominance under this model was theoretically enshrined in US economist Gary Becker’s (Reference Becker1981) specialization theory of family. Becker argued that families in industrial societies optimize household production and reproduction when one partner specializes in paid work and the other in unpaid family work such as housework and child care. The math behind the theory is gender-neutral in that either partner could specialize in paid or unpaid work depending on their individual aptitudes and preferences. However, reflecting the patriarchal world in which he was raised, Becker (Reference Becker1981) ultimately concluded women’s childbearing gives them a comparative advantage in family work, whereas the gender wage gap indicates men’s comparative advantage in employment. Governments in most, but not all, countries reinforced the patriarchal order in the post-World War II expansion of employment-based welfare provisions payable to the primary breadwinner (Cooke Reference Cooke2011).

Perpetuation of the male breadwinner model of family, though, requires a labor market that enables all members of a family to survive on a single income. This became possible for the newly-created European and North American middle classes beginning in the nineteenth century (Cooke Reference Cooke2011). The possibility extended to the working classes as well in the brief postwar period when workers enjoyed the fruits of their growing productivity (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014; Gottschalk and Smeeding Reference Gottschalk and Smeeding1997). Since then, the evolution from industrial to postindustrial labor markets made the patriarchal male breadwinner model of family increasingly unsustainable.

Deindustrialization and deunionization made less-skilled men the first to lose their ability to support a family. High-wage manufacturing jobs disappeared, replaced by growing employment in low-wage service sector jobs (Carlson, Chapter 1; Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). Neoliberal policies exacerbated less-skilled workers’ labor market losses. For instance, in a bid to enhance employer flexibility in competitive global markets, some governments eased employment protections and allowed the real value of minimum wages to fall (Immervoll Reference Immervoll2007). Wage inequalities widened further as returns to a university degree sharply increased beginning in the 1980s in the United States and Great Britain, and in the 1990s in other Western countries (Gottschalk and Smeeding Reference Gottschalk and Smeeding1997; Machin Reference Machin, Gregg and Wadsworth2010).

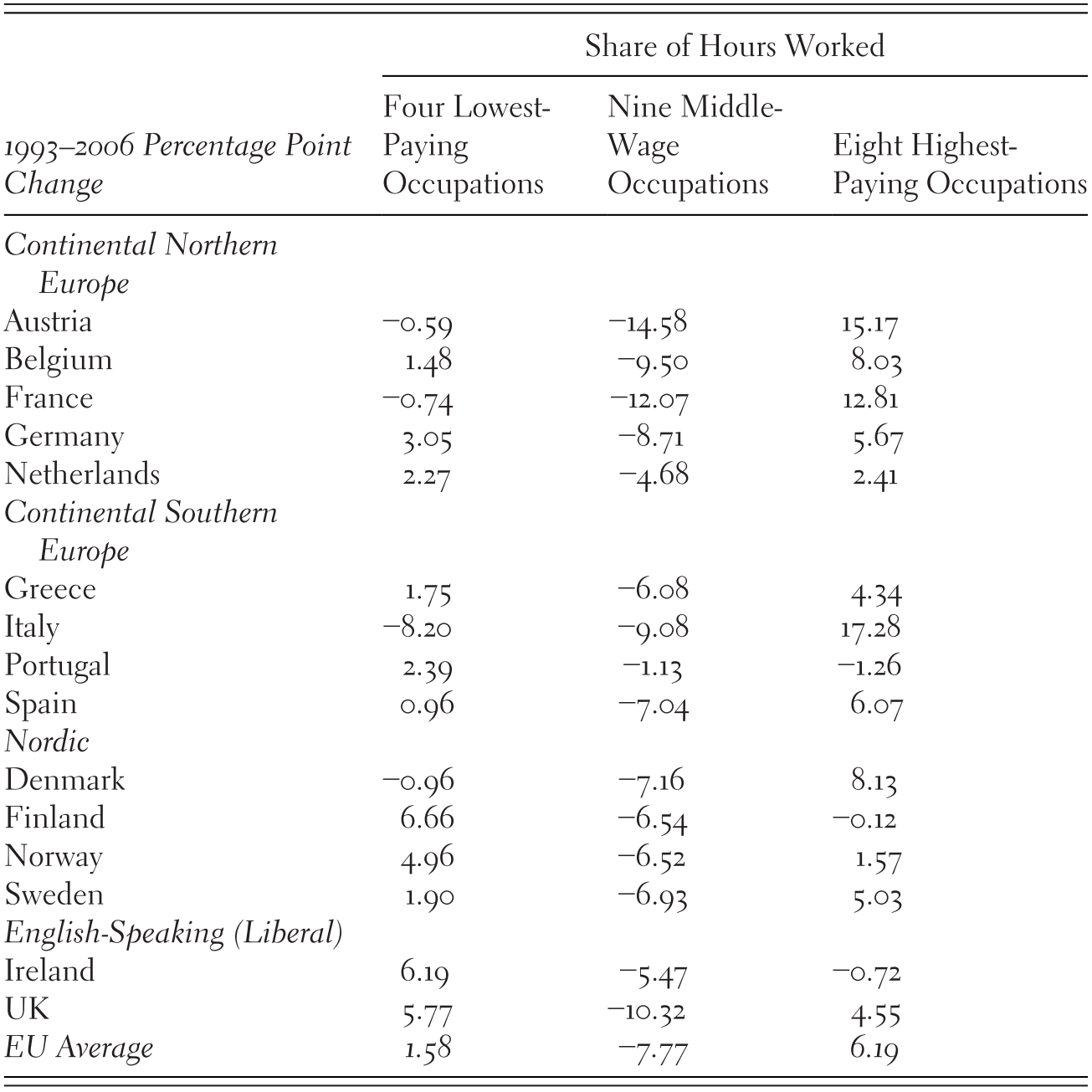

Nonetheless, the middle classes are not safe either. Since the late 1980s, technological expansion has led to falling employment shares among middle-waged occupations in North America (Autor Reference Autor2010) and Europe (Goos, Manning, and Salomons Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2009), but the specific pattern of polarization varies across Western labor markets, as indicated in Table 11.1. The loss of middle-waged occupations in Austria, France, and Italy was offset by strong growth in the highest-waged occupations. In contrast, the middle-wage job loss in Finland and Norway was offset by growth in only low-wage occupations. In the United Kingdom as in the United States (Autor Reference Autor2010), shrinking middle-wage employment was offset by approximately equal growth in both low- and high-wage jobs.

Table 11.1 Labor market polarization across Europe

Consequently, to varying degrees, postindustrial labor markets no longer support the patriarchal male breadwinner model as did the postwar labor markets. In almost every OECD country, the employment rate of prime-age (25 to 54) men decreased since the 1970s (OECD 2016b; see also Eberstadt, Chapter 5). The trajectories of younger adults making critical decisions about education, employment, and family are more precarious than at any other time during the past half-century (Eurofound 2016). The evolving labor markets, coupled with cultural and policy shifts, eroded men’s comparative advantage in employment. Simultaneously, gendered divisions of paid work narrowed.

Evolving Family Divisions of Labor

Any gender and other group hierarchies embedded in the institution of family are constantly contested (Connell and Messerschmidt Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005; Ferree Reference Ferree2010). In 1963, Friedan’s book on The Feminine Mystique struck a chord with Western housewives who felt trapped, alienated, and vulnerable inside their homes and economically dependent on husbands. Friedan (Reference Friedan1963) called for a revolution, for women to seize education and return to paid work. Friedan’s timing was perfect, coinciding with the introduction of the birth control pill, coupled with the easing of anti-contraception laws in many Western nations (Cooke Reference Cooke2011).

Women particularly embraced higher education. By the 1990s, women’s educational attainment in most Western countries had caught up with men’s. By 2011, college attainment among women aged 25–34 exceeded that of men in twenty-eight of thirty-four OECD countries (OECD 2013a). A consistent pattern across countries is that educated women are more likely to be employed than less-educated women (Cooke Reference Cooke2011; Harkness Reference Harkness, Gornick and Jantti2013; Pettit and Hook Reference Pettit and Hook2009). Nevertheless, growth of the service sector expanded job opportunities for less-skilled women, who take these jobs more often than similarly-skilled men (OECD 2016b). Consequently, and in contrast to men, women’s labor force participation rates steadily increased from the 1970s, as shown in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2 Female labor force participation rates over time (age 25 to 54)

The intersection of the state with family and market institutions is evident in the regional variation in these trends. As noted earlier, most postwar welfare state policies reinforced a male breadwinner model. The exception to this was the Nordic model offering extensive policy supports for maternal employment such as public provision of child care and paid parental leave (Cooke and Baxter Reference Cooke and Baxter2010). Consequently, Finnish and Swedish women’s labor force participation rates already exceeded 70% in 1975. The link between women’s education and employment is also weaker in these more egalitarian countries (Harkness Reference Harkness, Gornick and Jantti2013; Pettit and Hook Reference Pettit and Hook2009). At the other end of the policy spectrum, the very low 1975 labor force participation rates of Dutch, Italian, and Spanish women reflected the national policy reinforcement of the male breadwinner model at that time.

The power of policy to change behavior across diverse cultural and historical contexts is evident in the wake of the European Union’s 2000 Lisbon Treaty. The Lisbon Treaty contained an explicit goal of 60% female labor force participation in all member states by 2010, supported by expansion of public child care and other family policies found in the Nordic model.Footnote 3 The over-time trends presented in Table 11.2 indicate the Lisbon strategy had some success. By 2015, the labor force participation rate of women in almost all European countries exceeded that in the United States. Yet one downside of the employment growth in the service economy is the increase in part-time rather than full-time jobs. In all countries, women are more likely than men to work part-time. Still, the percentage of women’s total employment that is part-time varies from a low of 7.4% in the Czech Republic to a high of more than 60% among Dutch women (Table 11.2).

Persistent gender differences in hours employed contributes to the persistent gender wage gap in median earnings, indicated in the final column of Table 11.2. Even in the Nordic countries, the gender wage gap varies from a low of 6% in Norway, to a high of 20% in Finland. Finland’s gender wage gap is in fact larger than the gender wage gap in the less-regulated British and US economies. Nevertheless, women’s gains in employment and relative earnings over the past half-century are extraordinary, although gender employment equality remains elusive under even the most supportive policy framework to date.

One likely reason women made greater employment gains over the past few decades as compared with men is because of their greater predilection for education. Women might also navigate changing labor markets more successfully than men because of the growing employer demand for social in conjunction with cognitive skills (Deming Reference Deming2015). The gender response to US job polarization provides an example of women’s better adaptation. The decrease in middle-wage employment between 1979 and 2007 was more than twice as large for US women as men, 15.8% vs. 7%, respectively (Autor Reference Autor2010, p. 10). Nevertheless, female employment overwhelmingly moved up the occupational wage distribution as middle-wage employment fell. The decrease in US men’s middle-wage employment led to a more even split in employment growth in men’s low- and high-wage occupations (Autor Reference Autor2010). This highlights that the most-skilled men continue to make gains in the new economy, sustaining their advantage over high-skilled women. However, Autor (Reference Autor2010) found evidence of losses even among university-educated men, more of whom became employed in middle- and low-wage occupations. Future comparative work is needed to confirm whether these gender differences occurred in countries with varying patterns of polarization.

In any event, changing gender divisions of paid labor require some adaptation in how unpaid family work gets done. In this area as well, women have made greater behavioral changes than men. Unfortunately, men’s failure to become full partners in unpaid family work encourages greater class inequality among women within and across labor markets.

Gender–Class Redistribution of Unpaid Work

Goldscheider and Sassler (see Chapter 9) laud the continuing gender revolution indicated by slow but somewhat steady increases in Western men’s unpaid child care, most recently among less-educated men who historically professed the most conservative gender attitudes. Yet the decrease in women’s total domestic time during the revolution has been greater than the increase in men’s (Kan, Sullivan, and Gershuny Reference Kan, Sullivan and Gershuny2011). Multinational time diary data from the early 1970s through the early 2000s are available for the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, and United States. These data show that women in these countries on average reduced their 337 minutes per day of housework and child care by 60 minutes between the two time periods. Men in these countries increased their 117 minutes per day domestic contribution by 40 minutes across the period (Kan, Sullivan, and Gershuny Reference Kan, Sullivan and Gershuny2011, p. 236).

Not even the Nordic model has yet to eliminate gender inequality in unpaid work. Norwegian women in the early 2000s spent a similar amount of time as US women doing daily domestic tasks. Divisions were slightly more equal in Sweden, but because Swedish women spent appreciably less time doing these tasks than Norwegian or US women. The net result of these over-time shifts is that partnered women in all countries still perform 60% or more of household unpaid work. If future progress continues at the same rate as past progress – and this is a big “if” that Goldscheider and Sassler (see Chapter 9) fully embrace – gender equality in unpaid work would not be achieved for another half-century (Kan, Sullivan, and Gershuny Reference Kan, Sullivan and Gershuny2011).

The void created by men’s failure to contribute fully to family unpaid work is filled by the service sector, encouraging a growing class divide in women’s domestic equality gains. Gupta and his colleagues (Reference Gupta, Evertsson, Grunow, Nermo, Sayer, Treas and Drobnič2010) found that high-wage German, Swedish, and US women spend significantly less time doing routine housework than their lower waged peers. The institutional context matters, as differences among women are greater where aggregate income inequality is greater as in the United States (Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Evertsson, Grunow, Nermo, Sayer, Treas and Drobnič2010). The demand for market substitutes for domestic work is undoubtedly one driver of the low-wage job growth in Great Britain and the United States.

Class and also racial–ethnic divisions among women increasingly span continents, as the use of migrant domestic workers in affluent economies surged since the 1990s (Williams Reference Williams2012; Zimmerman, Litt, and Bose Reference Zimmerman, Litt and Bose2006). This includes an increase in the Nordic countries after governments introduced cash transfers to reduce the high cost of providing public care services (Williams Reference Williams2012). As a result, the number of migrant care workers increased in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden as well as other European and North American countries (Williams Reference Williams2012; Zimmerman, Litt, and Bose Reference Zimmerman, Litt and Bose2006).

The growth in migrant care work highlights that family inequalities in paid and unpaid work span First and Third World countries. If women in affluent economies struggle to balance employment and family, imagine the challenges for women doing so across national borders. Regardless of the care drain migrant work imposes on families in the sending countries, many governments actively encourage the migration of women over men (Williams Reference Williams2012; Zimmerman, Litt, and Bose Reference Zimmerman, Litt and Bose2006). This is because migrant women on average send more of their earnings back to their families, which improves the national balance of payments required under international financial aid packages. Migrant male workers, in contrast, are more likely to spend more of their earnings in the host country (Zimmerman, Litt, and Bose Reference Zimmerman, Litt and Bose2006).Footnote 4

Despite the downsides, all of the trends indicate that a growing number of women worldwide increasingly take advantage of postindustrial global labor markets. Of course, the highest-skilled men still benefit the most, but global markets increasingly tip the employment balance in favor of moderate- and less-skilled women over similar men. Global markets also allow high-wage women to fill the care deficit created by men’s limited unpaid work by purchasing support from less-advantaged women. At the same time, the proportion of younger less-skilled women continues to shrink at a faster rate than men’s (OECD 2013a). Policies also nudge women more than men. These evolving institutional effects shaping gender equality at its intersection with class (and race–ethnicity) are brought to bear on family formation patterns.

Institutional Effects on Class Inequalities in Family Forms

Becker (Reference Becker1981, Reference Becker1985) believed that the mutual dependence created by gender specialization in paid or unpaid work enhances marital stability and fertility. Certainly, the three-institutional reinforcement of Becker’s patriarchal model in the postwar decades reinforced a family formation sequence of marriage, childbearing, and children being raised by the two biological parents. This anomalous period in modern industrial history comprised the “golden age of marriage” in Western societies (Festy Reference Festy1980). Couples married earlier, leading to a spike in fertility in many countries (Van Bavel and Reher Reference Van Bavel and Reher2013). Whether the sequence reflected choice or constraint is debatable. Few women had the independent economic resources to remain single or to leave an unhappy or abusive marriage. Conception outside marriage was deeply stigmatizing for both the mother and the child, and most often resulted in either a “shot-gun” wedding or putting the child up for adoption.

Yet institutional intersections are dynamic. They vary across countries at any given point in time, as well as over time within countries. Esteve and Florez-Paredes (see Chapter 2) note that marriage was not historically preeminent in Central and Latin America. Instead, cohabitation and union instability were structural dimensions of family life when marriage reached its zenith in the West (Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2). During that time in the West, pronatalist policies combined with supports for maternal employment in Nordic and socialist countries correlated with higher nonmarital fertility rates (Cooke Reference Cooke2011; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). Relatedly, cohabitation in social democratic Denmark and Sweden began to increase in the 1960s, a decade ahead of other countries in Europe (Hall and White Reference Hall and White2005, p. 30).

Over the past fifty years, more women throughout Europe and the Americas cohabit rather than marry and raise children outside marriage whether because of divorce or nonmarital childbearing (Carlson, Chapter 1; Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). What intrigues or worries many social scientists and policymakers are the educational and/or racial–ethnic disparities in these family patterns that reflect and/or magnify inequalities among families. For most Whites in the United States and non-Nordic European countries, avant-garde family arrangements in the 1960s such as cohabitation or divorce were the purview of a small elite. As alternative family forms became more culturally acceptable and legally possible, Goode (Reference Goode1970) anticipated they would become more prevalent among the less- rather than highly educated. His prediction has largely been borne out, although educational gradients in marriage, cohabitation, nonmarital childbearing, and divorce vary in their institutional context (Carlson, Chapter 1).

Within a patriarchal structure, men’s economic capacity predicted by education still plays an important role in women’s family choices as Cherlin argues here and elsewhere (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). For example, Cherlin (see Chapter 3) attributes changes in the educational gradient in US single motherhood to the disparate gender earnings effects of job polarization. His prima facie case seems convincing. Recall that moderately educated women improved their earnings position in response to polarization while that of moderately educated men deteriorated (Autor Reference Autor2010). The percentage of US children living with moderately educated single mothers increased in each decade since the 1980s, whereas that for both the least- and most-educated women remained fairly stable since the 1990s (Cherlin, Chapter 3).

However, education predicts much more than economic outcomes – even in the United States – that also have a bearing on family commitment and stability. These associations should not be given short shrift in discussions of educational gradients in family formation because they offer much deeper insights as to the causes as well as consequences of observed family patterns. To date, Kalmijn (Reference Kalmijn2013) is the only demographer to explore the interplays between the institutional context and the possible meanings of education behind the gradients.

Beyond the Economics of Education

Kalmijn (Reference Kalmijn2013) noted that education predicts not only economic prospects, but more egalitarian attitudes as well. He subsequently hypothesized that the degree of gender inequality in a society determines which aspect of education accounts for educational gradients in family formation. In the twenty-six European countries analyzed, Kalmijn found that highly educated women in male breadwinner contexts were less likely to have ever married and, if they married, more likely to have divorced. In contrast, less-educated women in these contexts have fewer nonmarital economic alternatives and hence were more likely to have married and less likely to have divorced. Education had little impact on men’s marriage or divorce risks (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2013). This pattern is consistent with the educational scenarios in the United States at the height of the 1950s’ male breadwinner model.

In more egalitarian contexts, however, highly educated women and men were more likely to have married and less likely to have divorced (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2013).Footnote 5 Kalmijn (Reference Kalmijn2013) also found that highly educated individuals were more likely to be married to one another as gender equality increased. He concluded the stronger effect of men’s education on marriage in egalitarian countries relates to its cultural rather than economic implications. Educated women married educated men because the latter are more involved in child care and hold more egalitarian attitudes about their wives’ employment (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2013).

Missing from Kalmijn’s study due to data limitations are the many other characteristics associated with education that also affect marriage probabilities. Lower education predicts a range of problems, from disability and poor health (Eurofound 2016), to greater illicit drug use and binge drinking, particularly among young men (Duncan, Wilkerson, and England Reference Duncan, Wilkerson and England2006). Men with less education are more likely to commit domestic violence as well (Aizer Reference Aizer2010; Costa et al. Reference Costa, Hatzidimitriadou and Ioannidi-Kapolou2016).

These associations do not mean that forcing men to gain additional education will reduce the negative behaviors, as the causal arrow goes in the other direction. Behavioral and socio-emotional factors account for both education and employment outcomes, and behavioral problems are more prevalent among boys than girls (see Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013). Once young adults are engaged in illicit behaviors, they are the most difficult to reach with any education, training, or employment program (Eurofound 2016). At the same time, Cherlin (Reference Cherlin2014) summarized US qualitative research indicating that the persistent pressure on less-skilled men to fulfill the elusive patriarchal economic norm pushes them into illicit activities. This suggests outdated patriarchal norms do not support positive employment behavior among men.

Some academics and policymakers believe marriage “improves” men by encouraging them to give up bad habits and encourage their efforts to earn more money under the male breadwinner norm (Wilcox and Price, Chapter 8). For example, many studies find that married men earn more than either their single or divorced counterparts (Ahituv and Lerman Reference Ahituv and Lerman2007), although the magnitude of this marriage premium varies across countries (Schoeni Reference Schoeni1995) and among men within countries (Cooke Reference Cooke2014). However, a growing body of research finds that it is more a case of “better” men selecting into marriage rather than a causal effect of marriage. Duncan, Wilkerson, and England (Reference Duncan, Wilkerson and England2006) found that US men’s legal and illegal substance abuse significantly decreased before entering cohabitation or marriage, not after. In Norway, men who ultimately married had chosen higher wage occupations years before they partnered. Consequently, partnered men did not earn higher wages as compared with single men in the same occupations (Petersen, Penner, and Høgnes Reference Petersen, Penner and Høgnes2014). Similarly, US men tend to marry during periods of high wage growth, which plateaus (Dougherty Reference Dougherty2006; Killewald and Lundberg Reference Killewald and Lundberg2017) or even declines after the year of marriage (Loughran and Zissimopoulos Reference Loughran and Zissimopoulos2009).

All in all, more desirable men are selected into stable marriages, either because men who are particularly keen to have a family actively prepare for it earlier in the life course, or because savvy women actively pursue such men for marriage. Women who remain in education have the greatest opportunity to meet a large number of potentially desirable partners over several years before deciding on one. As societal gender equality increases and cultural norms about family evolve, less-educated women feel less compelled to legally commit to someone from their pool of likely partners. Less-educated women do marry, of course, but women most frequently cite drug or alcohol abuse, domestic violence, as well as poor employment prospects as reasons for divorce (Härkönen Reference Härkönen, Treas, Scott and Richards2014). The greater likelihood of these family-deleterious behaviors among less-educated men therefore contributes to educational gradients in marriage as well as divorce.

Patriarchy vs. Gender Equality

The body of evidence outlined above suggests the patriarchal norm of fathers as economic heads of households is incongruous with the educational and employment trends that highlight growing female advantage among low- to moderately educated adults. Men’s paid work is still important for family formation and stability, but it is increasingly important for women as well. For example, studies cited in Cooke and Baxter (Reference Cooke and Baxter2010) found that the unemployment of either husbands or wives increased the risk of divorce in Finland and Norway. What is at odds with labor market trends is the assumption of men’s wage advantage over women in general and their opposite-sex partner specifically.

A further problem with the patriarchal norm is that it precludes equally-valued roles for men’s expressive as well as economic contribution to family. Indeed, a new norm of family men as emotionally engaged and domestically involved has become pervasive since the 1970s, but it still sits subordinate to the patriarchal norm of breadwinning (Gerson Reference Gerson1993; Segal Reference Segal2007). As long as the patriarchal norm dominates, couples will find it culturally difficult to enact different divisions of household labor that might better suit their individual capabilities within postindustrial markets. Goldscheider and Sassler (see Chapter 9) discuss the compelling evidence that men in particular would enact more egalitarian domestic divisions if they believe that other men support these. This highlights that even the most-entrenched norms of masculinity can shift with public support from other men.

The economic and social trends together suggest that full institutional support for gender equality will ultimately support greater family stability in the postindustrial global economy. There is already some evidence that this is the case among younger cohorts. For example, US marriages where the woman has more education than the man are no longer more likely to divorce as they were a generation or two ago (Schwartz and Han Reference Schwartz and Han2014). At the same time, a US wife’s employment still increases the risk of divorce (Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Erola and Evertsson2013; Killewald Reference Killewald2016). This contrasts, however, with the effect of wives’ employment in countries with greater policy support for equality. In Finland, Norway, and Sweden, wives’ employment in fact lowers the risk of divorce (Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Erola and Evertsson2013). Even within the United States, Cooke (Reference Cooke2006) found that first marriages were most stable when couples had more equal divisions of paid and unpaid work. The optimal mix during the 1990s was when the wife contributed 40% to family earnings and the man 40% to unpaid domestic tasks (Cooke Reference Cooke2006).

However, it would be naïve to expect a smooth or rapid normative transition from patriarchal dominance to egalitarianism, particularly when some view the changes as entailing loss of public and private power. As noted by Carlson (see Chapter 1), cohabitation in lieu of marriage is widespread across the more egalitarian Nordic countries and cohabiting unions everywhere are less stable than married ones. In addition, Carlson’s (see Figure 1.3) data showed that the 2014 divorce rate per 1,000 people was higher in Denmark than in the notoriously divorce-prone United States. Even when limiting comparisons to the smaller proportion of Nordic couples who marry, Finnish and Swedish divorce rates are among the top of the list, although not as high as in the United States and Russia (Fahey Reference Fahey, Eekelaar and George2014, Figure 2).

In addition, other signs point to greater benefits of institutionalizing gender equality over patriarchy. Aizer (Reference Aizer2010) found that US domestic violence decreased when the gender wage gap decreased, whereas a traditional grab for patriarchal power would have predicted an increase. Esping-Andersen and Billari (Reference Esping–Andersen and Billari2015) highlight the recovery in fertility rates in the Nordic countries as compared with persistent low fertility in more gender-traditional European contexts.

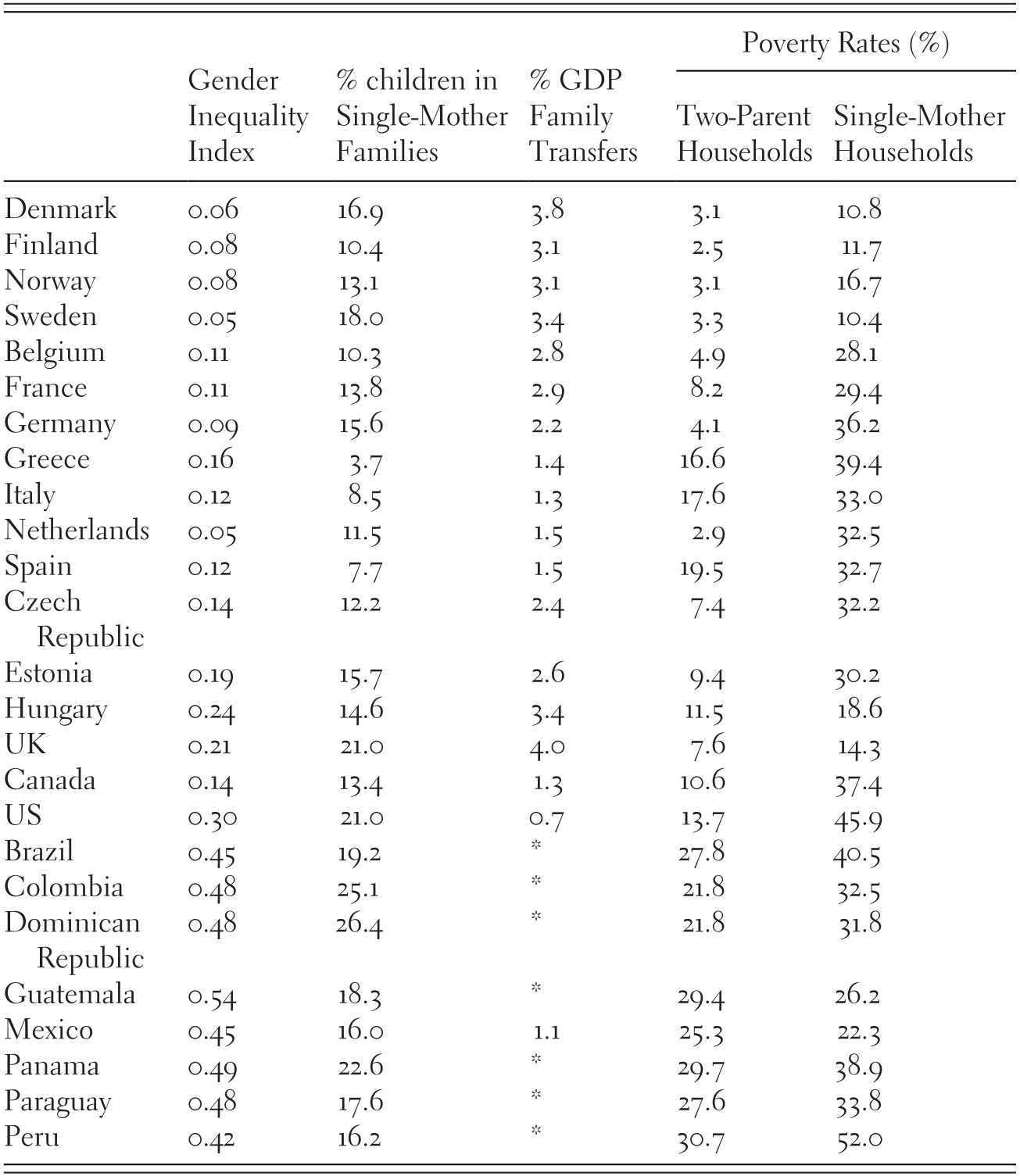

Further aggregate evidence of a positive link between gender equality and partnered households is contained in Table 11.3. The first column displays the United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index rating for numerous countries in Europe and the Americas. The index rates countries on women’s reproductive health, empowerment, and economic status,Footnote 6 and ranges from zero, indicating perfect gender equality, to one, indicating extreme gender inequality. The ratings confirm the high degree of gender equality in the Nordic countries, along with the Netherlands and Germany. Most of the rest of Europe along with Canada have moderately high gender equality, whereas it is noticeably lower in Hungary, the United Kingdom, and United States. It is lowest in familistic Latin America.

Table 11.3 Gender inequality, social expenditures, and percentage of children under 17 living in poverty in two- vs. single-parent families, circa 2010

The second column displays the percentage of children under the age of 17 who are living in a single-mother household. The percentage is smallest in Greece at less than 4% and greatest in Colombia and the Dominican Republic where more than one quarter of children reside with a lone mother. The United Kingdom and United States are more similar to Latin America, with more than one fifth of young children residing in single-mother households. Overall, the percentage of children residing in single-mother households increases as gender inequality increases (correlation 0.64, p <0.000).

Whether institutionalized gender equality or patriarchy supports greater family stability in postindustrial societies is much more than an academic debate. The core issue behind the debate is the relationship between family forms and the individual outcomes noted in the bottom box of Figure 11.1 (see also Chapter 10). A sizeable literature documents that father absence predicts greater risks of behavioral, educational, and employment problems in the next generation. My final argument, building on an insight from Moynihan, is that any pathology associated with residing in single-mother households is an artifact of patriarchy that limits these households’ access to resources. Proof of this conjecture is that the negative outcomes are minimized where cultural, market, and state institutions instead support greater gender equality.

Institutional Intersections and Group Differences in Family Outcomes

Senator Moynihan’s Reference Moynihan1965 report for the US Department of Labor brought discussion of child outcomes associated with single-mother households into the public debate. In that report, he noted the very high divorce and nonmarital birth rates among African–American families as compared with Whites, and the strong correlations between father absence and children’s low intelligence scores, school truancy, crime, drug addiction, etc. (Moynihan Reference Moynihan1965). There were very strong educational gradients in effects that he attributed to the deep-seated US racism undermining African–American men’s access to education and employment and, in turn, their relative employment advantage over African–American women. Moynihan (Reference Moynihan1965, p. 29) concluded the poor intergenerational outcomes were indicative of the “pathology of matriarchy” within a society that presumed and rewarded male leadership in public and private life. Moynihan did not consider patriarchy superior or inevitable, just normative at the time. One of his key insights was that it was the mismatch between individual and current normative circumstances that accounted for the ill effects, not a pathology inherent to matriarchy.

In this chapter, I have detailed the similar dismantling of economic rewards since Moynihan wrote his report for a growing proportion of men based on education, along with the sizeable increase in women’s public participation and private power. Yet the assumed pathology of matriarchy persists in much of the US literature even as accumulating evidence indicates norms are giving way to more gender-egalitarian family arrangements. McLanahan (Reference McLanahan2004) gave it a less provocative name of “diverging destinies,” with the likelihood of father absence predicated on mothers’ education rather than race–ethnicity.Footnote 7

To be sure, studies from a range of Western countries confirm that parental separation and subsequent family transitions predict some risk of negative effects on children’s psychological well-being, behavior, grades, test scores, educational attainment, own early onset of sexual activity, early childbearing, and risk of divorce in adulthood (Garriga and Berta, Chapter 6; Härkönen, Bernardi, and Boertien Reference Härkönen, Bernardi and Boertien2017; McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). McLanahan (Reference McLanahan2004) contends the negative outcomes derive from the lower resources of single-parent households, in terms of both money and parental attention. As less-educated women are more likely to be single parents, their children face a larger resource deficit.

Confirming the causal direction of effects, however, is tricky (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Figlio, Karbownik, Roth and Wasserman2016; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). Lower socioeconomic status already predicts worse outcomes for children whether in two- or single-parent households. Another possibility is that some other characteristic might account for both family instability and children’s outcomes (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Figlio, Karbownik, Roth and Wasserman2016; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). Analyses controlling for children’s stable unobserved characteristics, prior behavior, or school performance indeed find smaller effects than when comparing across children (Härkönen, Bernardi, and Boertien Reference Härkönen, Bernardi and Boertien2017; McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013). In other words, these children would have done worse regardless of family structure.

Furthermore, like patriarchy, the negative effects associated with spending time in a single-mother household are not inevitable. Most studies report “average” effects. In all countries, a sizeable minority if not majority of children experiencing family instability do just fine or perhaps better than had their fathers been present (Härkönen, Bernardi, and Boertien Reference Härkönen, Bernardi and Boertien2017). Furthermore, more redistributive welfare states and greater policy support for maternal employment minimize the negative intergenerational effects because they increase available resources (Härkönen, Bernardi, and Boertien Reference Härkönen, Bernardi and Boertien2017; Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado Reference Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado2018). In Europe, this realization resulted in the adoption of a policy discourse around social investment rather than social protection. Whereas traditional welfare policies aimed to reduce current family poverty, social investment policies aim to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty (Jenson Reference Jenson2009). The goal is to ensure current and future employment growth within a (skilled) knowledge economy (Bonoli Reference Bonoli2005). Patterned on the Nordic model, social investment policies stress greater education and skills for the next generation, simultaneous with current high levels of female labor force participation facilitated by more policy supports for employed parents and carers (Bonoli Reference Bonoli2005; Jenson Reference Jenson2009).

The impact of public investment on families’ economic resources is evident in the final three columns of Table 11.3. The third column indicates the percentage of GDP spent on family transfers in each of the countries (information not available for Latin America). Note the particularly low level of US public investment (0.7% of GDP in 2010) as compared with Europe and Canada. With this low level of public investment comes a high level of poverty even among US two-parent households – commensurate with the far less affluent Mediterranean countries struggling under austerity measures. The poverty rate for US single-mother households was a staggering 45.9% in 2010, exceeding that of any country in the table except Peru. In contrast, poverty rates of single-mother households in the redistributive Nordic countries were on average similar to the US poverty rate for two-parent households.

These aggregate differences manifest at the individual level. McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider’s (Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013) review consistently found significant negative effects of father absence on US children’s educational and mental health outcomes, but effects were often weaker or entirely absent in other countries. For example, the educational penalty for father absence is twice as large in the United States as in Germany or the United Kingdom (Bernardi and Boertien Reference Bernardi and Boertien2017a). What research is just beginning to untangle is how child outcomes differ systematically at the intersection of gender and class (and race–ethnicity).

Gender–Class Gaps in Effects

Ascertaining possible gender or class differences in the impact of family structure on child outcomes is difficult because both characteristics predict behavioral and educational differences irrespective of family structure. As already mentioned, children benefit from economic and parental resources, the level of which increases as parents’ education increases. Consequently children of less-educated parents on average have more behavioral problems and complete less education than children of highly educated parents. Whether father absence magnifies this class disadvantage is unclear.

Two recent literature reviews found that approximately half of the reviewed studies concluded that children of less-educated single parents fare worse, whereas the other half concluded that the absence of a highly educated father is more detrimental (Härkönen, Bernardi, and Boertien Reference Härkönen, Bernardi and Boertien2017; McLanahan, Tach, and Schneider Reference McLanahan, Tach and Schneider2013). Bernardi and Boertien (Reference Bernardi and Boertien2017a) contend the varying conclusions stem from the different methods used in the analyses. Once controlling for this, they found that father absence had the least impact on the educational attainment of children of less-educated mothers in Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and United States (Bernardi and Boertien Reference Bernardi and Boertien2017a). Whether future research with similar attention to methodological issues will reinforce this conclusion is an empirical question.

Gender differences in the impact of residing with a single mother are apparent, however, at least in the United States. These develop from biological differences wherein boys do worse than girls on a range of noncognitive measures affecting school success (Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013). US boys are more likely than girls to be diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and have lower levels of inhibitory control and perceptual sensitivity, which equates to greater aggression (see Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013). US girls also have a slight but reliable advantage in delaying gratification (Silverman 2003, cited in Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013). Bertrand and Pan (Reference Bertrand and Pan2013) contend that some of the growing gender differences in educational attainment discussed earlier can be traced to these noncognitive gender differences in children.

The source of the gender behavioral differences may be biological, but as with all essentialist differences, behaviors are responsive to environmental factors. US evidence indicates that boys’ outcomes deteriorate further with the reduction in parenting resources of single-mother households (Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013; Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Osborne, Beck and McLanahan2011). Not only is there just one parent, but single US mothers engage less with boys than girls from a very young age, although parental time investment increases with mothers’ education (Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013). Consequently, US girls generally fare better than boys in single-parent households. Girls’ greater resilience in the face of family change contributes to their educational success and adaptability to changing labor markets that demand high skills (Bertrand and Pan Reference Bertrand and Pan2013).

Looking at effects at the intersection of gender and class using detailed Florida student records, Autor and colleagues (Reference Autor, Figlio, Karbownik, Roth and Wasserman2016) found that the gender gaps in academic and behavioral outcomes in both single- and two-parent families shrink as parental socioeconomic status increases. Overall, boys’ outcomes are more strongly contingent on family structure as well as economic resources, although high-quality schools can somewhat narrow the gender gap (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Figlio, Karbownik, Roth and Wasserman2016). The smaller impact of schools as well as neighborhoods on US boys’ behavioral and academic outcomes indicates that Reeves’ (see Chapter 10) suggestion of sending disadvantaged children to boarding schools would not rectify the inequalities. Doing so may particularly harm boys because it would remove both parents from their daily lives.

These gender differences in child outcomes may be another case of US exceptionalism, driven by the high levels of class and gender inequality in that country. Comparative research is needed to ascertain whether the more egalitarian policy contexts specifically minimize the negative impact of single motherhood on boys. It does seem likely that the perpetuation of the patriarchal norm in unequal contexts such as the United States contributes to the intergenerational gender differences. The expectation that men should be the primary family breadwinner in markets with a high degree of income inequality sharply reduces women’s perceived benefit of committing to less-educated men. Men’s failure to achieve the patriarchal ideal coupled with their biological predisposition to act out increases the risk they will engage in further negative behaviors that limit their time with residential or nonresidential children. The next generation of boys suffers the most from father absence in contexts of high inequality, perpetuating the cycle of maladaptation as institutional support for patriarchal entitlement in the family, market, and state continues to ebb. However, the solution is not to return to the patriarchal system built on gender inequality. Instead, what is needed is to fully institutionalize gender equality in which new, more adaptive masculinities can develop.

Family Futures: Making Gender Equality a “Complete” Institution

In this chapter, I have highlighted how group inequalities configured at the intersections of family, market, and state institutions vary across place and evolve over time. My argument is that the institutional arrangements supporting patriarchy in the postwar decades have been crumbling for quite some time. A high-skill, technologically-driven global economy requires brains rather than brawn, and adaptable, socially engaged service providers. In Western societies, many of the requisite traits are traditionally feminine. Indeed, in the past half-century we have seen a remarkable ascendancy of women in the economic, social, and political order.

As the new institutional order unfolds, the value of education continues to increase (Autor Reference Autor2010; Gottschalk and Smeeding Reference Gottschalk and Smeeding1997; Machin Reference Machin, Gregg and Wadsworth2010). Education not only imparts skills, but encourages more egalitarian attitudes and predicts more positive social behaviors as well. Yet men’s educational attainment has not kept pace with women’s over the past few decades. Consequently a sizable proportion of men struggle to adapt to the new socioeconomic demands in and outside the home.

The gender revolution is far from complete, but many women perceive themselves as sufficiently independent to go it alone at some stage of raising their children when their partners fall short of economic or behavioral expectations. Although much more comparative research is needed, available evidence finds that boys’ essentialist behavioral problems magnify when fathers are absent from the household. These behavioral problems eclipse boys’ educational development, which blunts the possibility that a larger proportion of the next generation can enjoy the greater family stability associated with greater educational attainment.

This vicious circle of intergenerational inequality down the male line does not indicate a pathology of matriarchy as initially suggested by Moynihan in the mid-1960s. It instead point to the growing pathology of patriarchy in postindustrial economies, because better institutional supports for gender along with class equality yield the best intergenerational outcomes. The reason we have not yet eradicated the risks is because gender equality remains an “incomplete institution” even in the most progressive contexts. I borrow this term from Cherlin’s (Reference Cherlin1978) seminal article on remarriage after divorce. In that article, Cherlin argued that remarriages were less stable than first marriages because they lacked the institutional support in language, law, and custom that benefited first marriages. Similarly, I hold that the detrimental behaviors among boys and men will be staunched only once gender equality has become fully institutionalized in the family, market, and state. Institutionalizing gender equality eases the pressure on men to dominate paid work, allowing more adaptive masculinities to develop in which men’s equal contributions to both paid and unpaid work support family stability. I conclude with some brief thoughts on the major market and policy challenges to achieving this.

The first challenge is to enhance children’s and particularly boys’ educational engagement from preschool that will carry them through to complete higher levels of education. This perspective is core to the EU’s social investment strategy, but as someone who worked on educational reform in her pre-academic career, I can attest that the challenge is not the what, but the how. Most compulsory educational systems developed with the assumption of an at-home mother (Cooke Reference Cooke2011), and that children would adapt to the school structures and processes. Both of these assumptions undermine academic achievement.

Instead, educational processes need to adapt to children’s and families’ needs. This includes additional public funding for more aides of both genders in the classroom, innovative approaches to curriculum delivery, high-quality care and learning opportunities before and after standard school days, further supports for children with any type of special need (including behavioral), and coordinated extracurricular activities that do not require parents to shuttle children to and from venues. These supports should extend through adolescence, during which young persons are at greatest risk of becoming NEET – not in education, employment, or training (Eurofound 2016).

The second challenge is that both parents need more workplace flexibility to ensure they can be actively involved in their children’s daily lives. At present, organizations still reinforce patriarchal expectations of an ideal worker without competing family demands (Acker Reference Acker2006). These expectations manifest in disparate gendered penalties when employees seek workplace flexibility. For example, one US study found that male employees who experienced a family conflict received lower performance ratings and lower reward recommendations, whereas ratings of women were unaffected by family conflicts (Butler and Skattebo Reference Butler and Skattebo2004).

There is also a strong class dimension to organizational gendered expectations. Glass (Reference Glass2004) found that mothers in professional or managerial occupations incurred slightly larger wage penalties when they worked reduced hours or worked from home, as compared with mothers in other occupations who took up similar workplace options. Similarly, Brescoll, Glass, and Sedlovskaya (Reference Brescoll, Glass and Sedlovskaya2013) found that employers were more likely to grant low- than high-status men’s requests for flexible work schedules for family reasons. High-status men were more likely to be granted leave for career development (Brescoll, Glass, and Sedlovskaya Reference Brescoll, Glass and Sedlovskaya2013).

This nascent literature supports Goldscheider and Sassler’s optimism (see Chapter 9) that the second half of the gender revolution is now unfolding among less-educated couples, which should ultimately reduce educational gradients in marriage and divorce. At the same time, workplaces are stymying further gender equality progress among the more highly educated, beyond providing market alternatives for domestic production that widen class gaps among women (Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Evertsson, Grunow, Nermo, Sayer, Treas and Drobnič2010). Persistent patriarchal advantage at the top of the class hierarchy blocks the thorough institutionalization of gender equality. One way to quell this is with more aggressive redistributive tax policies, the proceeds of which could be fed into the educational system.

Also needed are more aggressive positive discrimination policies, but targeted at the top of the occupational structure. Affirmative action entered US equality legislation with Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246, although it has subsequently come under fire as discriminating against unprotected groups. Positive discrimination is also allowed under the European Commission’s 2006/54/EC directive on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation. Again, however, many countries have argued against positive discrimination because in principle it violates men’s rights to equality (Cooke Reference Cooke2011).

Gender equality at the executive level remains most elusive. The European Union is ahead of the Americas in tackling this with specific targets of increasing the percentage of women in key decision-making positions (European Commission 2016). In 2003, Norway mandated that 40% of nonexecutive board positions be filled by women. Although that controversial law is now considered a success, its implementation has not trickled down to increase the percentage of women in executive positions (Bertrand et al. Reference Bertrand, Black, Jensen and Lleras-Muney2015). Women’s ability to succeed when appointed to executive positions is contingent on eliminating the patriarchal organizational norms for executives as noted above.

The resistance to positive discrimination highlights the cultural resistance to fully disavowing patriarchy, a cultural resistance that has proven slow to change. Goldscheider and Sassler (see Chapter 9) discuss the gender essentialism behind such resistance, so I will not repeat the arguments here. However, as they also argue and as indicated throughout this chapter, both markets and policies can drive us further along the path to gender equality and, in turn, better family outcomes. Only when gender equality is fully institutionalized in markets and policies can the family, however configured, and all of its members, thrive.

This volume has explored the nature, causes, and consequences of family inequality in the Americas and Europe. Family inequality, measured both in economic terms and in family structure, can be found in many countries across these three regions, but it is most pronounced in the United States and Latin America (Boertien, Bernardi, and Härkönen, Chapter 7; Carlson, Chapter 1; Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2). That is, although gaps in family income between more and less affluent families exist in all countries, they are especially large in the United States and Latin America (Carbone and Cahn, Chapter 13; Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2). Likewise, single parenthood and family instability are now more common among those without a college education throughout most of the Americas and Europe, but inequalities in these particular dimensions of family structure seem to be especially prevalent in the United States and Latin America (Carlson, Chapter 1; Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). Overall, then, less-educated men, women, and their children in these three regions are more likely to be “doubly disadvantaged” – having fewer socioeconomic resources and less family stability, compared to their better-educated fellow citizens (McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004; Perelli-Harris 2018) – and this pattern of double disadvantage is most common in the United States and Latin America.

Although this volume chronicles an array of economic, policy, and cultural factors that help to account for this dual pattern of economic and family inequality, it does not focus much on the role, if any, that the retreat from marriage unfolding across much of the globe since the 1960s (Goode Reference Goode1993; Wilcox and DeRose Reference Wilcox and DeRose2017) has itself played in fueling both family economic inequality and family structure inequality between more- and less-educated Americans and Europeans. The major exception is Eberstadt’s chapter (See Chapter 5), which touches on the ways the decline of marriage among less-educated Americans may help explain the growing divergence in labor force participation among men with and without college degrees in the United States (Lerman and Wilcox Reference Lerman and Wilcox2014). Otherwise, not much attention is paid to the role that the decline of marriage may have played in fueling or locking in patterns of economic and family structure inequality.

Nevertheless, the retreat from marriage that has been unfolding in the Americas and Europe over much of the last half-century may well be an important contributor to growing inequality in family structure between more- and less-educated North Americans and Europeans – and high levels of family inequality between Latin Americans. That is because when marriage is less likely to anchor the adult life course, and less likely to ground and guide the bearing and rearing of children, family instability and single parenthood seem to follow in its retreating wake (Heuveline, Timberlake, and Furstenberg Reference Heuveline, Timberlake and Furstenberg2003). DeRose and colleagues (Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017), for instance, find that in the United States and Europe, children born to cohabitating couples are, on average, about 90 percent more likely to see their parents split by age 12 compared to children born to married couples. Moreover, as cohabitation becomes more common and marriage becomes less common in countries across the globe, family instability generally increases (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017). In other words, less marriage seems to equal more family instability and single parenthood for children.

Why is this? Marriage is characterized by a distinctive set of norms, customs, and often legal rights and responsibilities that appear to make it more stable than cohabitation (Nock Reference Nock1998). For instance, unlike cohabitation and dating, entry into marriage is marked by a collective ritual that signals to self, partner, friends, and family that a new state in life has been entered into. Above all, marriage is generally seen to signify greater commitment than the relational alternatives: It functions as a commitment device (Lundberg, Pollak, and Stearns Reference Lundberg, Pollak and Stearns2016). Indeed, Perelli-Harris (see Chapter 4) notes that her focus groups with men and women across nine European countries indicate that “participants in all countries generally saw cohabitation as a less committed union than marriage.” This, then, is probably why in countries as different as France, Italy, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States, children born to married parents enjoy markedly more stability than children born to cohabiting parents (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017).

In turn, the rise of cohabitation and the retreat from marriage seems to have affected the less-educated more than the college-educated in many American and European nations, at least as it relates to family instability and single parenthood. The number of families headed by single parents has increased and is markedly higher among those without college degrees in countries as different as Mexico, Sweden, and the United States (Carlson, Chapter 1; Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2; Kennedy and Thomson Reference Kennedy and Thomson2010; Wilcox Reference Wilcox2010). Although the negative relationship between education and family instability/single parenthood is not universal throughout Europe and the Americas, it does seem to be increasingly the norm (Carlson, Chapter 1; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4).

Why is family structure increasingly patterned along educational lines? This development is true partly for economic reasons – for instance, less-educated men face higher levels of job instability, which affects both their marriageability and the stability of their families (Carbone and Cahn, Chapter 13; Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4; Wilcox, Reference Wilcox2010). However, cultural reasons also seem to matter: The ethos of freedom and choice related to questions of sex, parenthood, and relationships valorized amidst the “second demographic transition,” and the deinstitutionalization of marriage this ethos has fueled, can be more difficult for the less educated to navigate when it comes to childbearing, marriage, and the establishment of stable families (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004; Lesthaeghe and Neidert Reference Lesthaeghe and Neidert2006; Sassler and Miller Reference Sassler and Miller2017). Future research will have to explore how much, and to what extent, the declining cultural, legal, and economic power of marriage has contributed to growing family structure inequality in much of the Americas and Europe.

Likewise, more needs to be learned about how the retreat from marriage, along with the increasingly stratified character of family structure, has affected economic inequality between families in Europe and Latin America. In the United States, growing family structure inequality appears to have played an important role in increases in family income inequality from the 1970s to the 2000s. The scholarship suggests that between about one fifth (Western, Bloome, and Percheski Reference Western, Bloome and Percheski2008) and four tenths (S. P. Martin Reference Martin2006) of the growth in family income inequality over this period can be connected to the growing proportion of single-parent families among less-educated Americans. Because less-educated Americans have experienced much higher levels of family instability and single parenthood than their college-educated peers since the 1970s, their median family incomes are markedly lower than they would otherwise be, especially compared to their college-educated peers who are now much more likely to benefit from two incomes (Lerman and Wilcox Reference Lerman and Wilcox2014). By contrast, if they enjoyed levels of family stability as high as their college-educated fellow citizens, family income inequality in the United States would be smaller.

It is less clear, however, if and how increases in family structure inequality have influenced economic inequality in Europe and Latin America. In Europe, it is possible that increasing family structure inequality may not have led to greater family economic inequality, at least when it comes to family income, because welfare state spending has increased commensurate with the growth in single-parent families (Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2014). In Latin America, family income inequality has declined in recent years, largely because less-educated workers, including women, are working more and earning more, and welfare state spending has grown (Azevedo, Inchauste, and Sanfelice Reference Azevedo, Inchauste and Sanfelice2013; Lustig, Lopez-Calva, and Ortiz-Juarez Reference Lustig, Lopez-Calva and Ortiz-Juarez2013). However, given increases in women’s labor force participation among less-educated women, it is possible family income inequality in Latin America would have been reduced even more than it was were it not for the fact that more and more Latin American mothers are single, especially the less-educated (Esteve and Florez-Paredes, Chapter 2). More research is needed to determine if growing family instability in Europe and Latin America has led to greater inequality in family economic well-being between the more and less-educated. Such research needs also to extend beyond income to include considerations of how changes in family structure may influence patterns of inequality in family assets between the highly educated and the less educated.

This volume shows that families across the Americas and Europe are more fragile. This is in part because marriage is less likely to anchor the adult life course, and to ground and guide the bearing and rearing of children in countries across these three continents. What is more, in many countries in the Americas and Europe, family life is particularly fragile among the less educated. This has led to family structure inequality in many countries – from Sweden to the United States – such that highly educated men and women continue to enjoy strong and stable families whereas their less-educated fellow citizens do not. However, it is not clear that growing inequality in family structure uniformly leads to growing family economic inequality in income and assets in these three continents. More research is needed to determine if public policies can and do minimize the economic fallout of growing family structure inequality on economic inequality in Europe and the Americas. In other words, it is not clear if less marriage always need equal more family economic inequality in nations across these three continents.

Throughout the developed world, inequality is increasing and the family is changing. Yet, there is no agreement on the links between the two. Some claim that family change – particularly class-based increases in relationship instability, nonmarital cohabitation, and single-parent births – contributes to societal inequality. Accordingly, a renewed emphasis on marriage should be an important part of any solution. Others see economic change as the source of both greater inequality and family transformation, and favor solutions that provide greater support to those left behind – both for poverty alleviation and to enhance relationship stability. Both groups agree that a new information-based society has witnessed a series of overlapping changes: A greater demand for women’s market labor, an elite shift to later marriage and relatively more egalitarian relationships, declining wages for unskilled men, greater tolerance for nonmarital sexuality, and lower overall fertility. Yet, they differ in the way they address the relationship between economic change and family values. Some scholars see the values change as a product of the economic changes; elite couples have delayed marriage and childbearing and embraced more cooperative and flexible parental roles in order to be able take advantage of dual career opportunities. We call this “blue” family values (Cahn and Carbone Reference Cahn and Carbone2010). In accordance with this view, the instability in working-class families involves problems of transition; many societies do not provide sufficient support to systematize the advantages of the new family system, which depend on women’s reproductive autonomy, the creation of meaningful social roles for blue-collar men, and greater parental security irrespective of family form. Others view the change in terms of values as independent of the economic changes, and favor stronger support for more responsible decisions about partnering and child-rearing. While the approaches overlap, they differ in their identification of causation, preferred family strategies, and proposed government interventions. Accordingly, while both see increasing working-class instability in employment, residences, and family composition as bad for children, they differ as to whether greater economic insecurity or cultural shifts in family composition play the larger role in increasing that instability.

Testing the relative merits of these viewpoints in a comparative context is challenging. Academic study of the increase in inequality is relatively new, and the study of the connections between inequalities of the family is even more contemporary. Moreover, while economies and families are changing almost everywhere, they are not necessarily changing everywhere in the same ways or at the same rates (Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4). Even within the same countries, for example, urban areas tend to be earlier adopters of the new family model than rural areas; and this may be true whether the urban areas are struggling or thriving (Cahn and Carbone Reference Cahn and Carbone2010; Kurek Reference Kurek2011). Indeed, family scholars do not even agree on what to call the “new family behaviors” (Perelli-Harrris, Chapter 4), sometimes terming them the “deinstitutionalization of marriage” (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2005), “the second demographic transition” (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2010), or something else entirely.

To make sense of the inquiry, an interdisciplinary and international group of scholars came to together in Rome, Italy. In this volume, they provide a comparative analysis of the relationship between growing economic inequality in a large portion of the Western world and the process of family change. Unsurprisingly, they provide no comprehensive resolution of the debate over the implications of family change or the solution to economic inequality. Yet, they create a much more informed foundation for these discussions. Based on the contributions to this volume and our past scholarship in the area within this Commentary, we highlight where grounds emerge for at least tentative agreement, the issues likely to remain subjects of intense disagreement, and the areas which have yet to be fully explored. In doing so, we draw our examples primarily from the United States, although we recognize that it is often an outlier in both economic and family terms. Our goal is to shift the focus from the areas of disagreement toward positive policies with proven impact.

This Commentary breaks the debate down into three areas. We term the first “The View From 10,000 Feet.” This section provides an overview of where some agreement is likely. A major part of the debate to date has been between those who see family change as a product of cultural shifts and those who view it as a reaction to a new, postindustrial economic model. Our response, which frames this Commentary and which we explore in this Section, is an emphatic “yes.” Economic and cultural changes interact; viewing them as independent of each other is neither necessary nor sustainable. We conclude, therefore, that some agreement should be possible at the 10,000 foot level, and such agreement could involve recognition that the changes we see in the family are part of a transition to a new economy. There also seems to be agreement that this new economy causes reorganization of families’ division of market and domestic work, with profound implications for investments in children.

In the second section, “The Nitty-Gritty,” we consider the need to develop a dynamic analysis that examines the interaction of cultural, social, economic, and legal factors, rather than the isolation of individual causal agents. We note that determining causation in family change is always challenging. Nonetheless, most scholars agree that a significant factor underlying family composition is the status of women. However, accounting for the impact of change in women’s roles is complicated because it involves not only relationships between men and women but also how those relationships affect both men’s relative status among men, and women’s ability to command societal support for their child-rearing efforts. We conclude that international, regional, and class comparisons are incomplete unless they take into account the societal and legal context for intimate relationships, as some chapters in this volume do.

In the third section, “Why Can’t We All Get Along?” we observe the forces blocking comprehensive approaches to the family. If we see what is happening to the family as part of a process of economic and cultural change, the question should be whether it is desirable or possible to speed the transition to the new system of gender egalitarianism and public support for the transition to an information economy for those who might be left behind. In fact, some countries seem to have cushioned the transition to the new system; either because the values underlying the new system are more broadly shared, or because the society provides a greater degree of family support. In other countries however, the process of economic and family change has triggered greater divisions, blocking public support for a more comprehensive approach. We conclude by reviewing the proposals in this volume and their prospects for implementation.

The View from 10,000 Feet

Efforts to describe the family in comparative terms are a fraught enterprise, as they must account for cultural, economic, and legal changes in differing countries with diverse heritages. It is understandable therefore that the papers do not agree on an overall framework as to what exactly has caused changing family structures. Indeed, to the extent they agree on anything, it is most likely to be certain basic facts, and identification of the theories whose predictions cannot be validated. We therefore start with the factual assertions on which there is at least some agreement, then move on to the claims that do not stand up to examination, and close with the identification of the missing parts of a full analysis.

To the extent that there is a shared set of assumptions for this volume, they are basic. First, the family has changed. Between 1980 and 2000, fertility declined substantially across most of the developed world, though with greater variation after 2000. Nonmarital cohabitation and childbearing increased during the same period in every developed country. The patterns, however, are not uniform. Sweden and Iceland, which had much higher rates of nonmarital childbearing compared to other European countries in 1980, did not experience a sharp increase. The growth in nonmarital births is leveling off in both Sweden and Iceland (Perelli-Harris, Chapter 4, Figure 4.1).

Second, all developed countries experienced similar economic changes with a reduction in middle-wage jobs. The countries varied, however, in the degree to which they experienced a corresponding increase in higher or lower wage occupations (Cooke, Chapter 11, Table 11.1). France and Denmark, for example, experienced large increases in high-paying occupations, the Republic of Ireland and Finland saw their low-paying jobs expand most; while both high-paying and low paying jobs grew in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.