1 Introduction

Change agents: Applying cross-sector collaboration.

Video available at www.cambridge.org/Kritz_2nd_edition

Every urban slum creates challenges too complex for governments to resolve when working alone. Old Fadama, an informal settlement in Accra, Ghana, was established in the 1980s by migrants fleeing tribal violence in the north. It has grown steadily with spikes for a variety of reasons, including a period of intense domestic conflict in 1994 and drought conditions in 2015. Home to 79,684 residents when last enumerated in 2009 (Reference Farouk and OwusuFarouk & Owusu, 2012), in 2015 the Accra municipal government estimated that the number of residents expanded to 150,000. These included long-term settlers and multigenerational families as well as seasonal migrants coming from throughout the country. These short-term residents were motivated by regular crop cycles to sell produce at the nearby Agbogbloshie green market. Others sought access to health care, education, or work. Many Old Fadama residents did not speak English or the local languages in Accra.

Old Fadama had virtually no water or sanitation infrastructure (see Figure 1), so excreta were collected in plastic bags and disposed of in the river that bordered the slum, creating heavy silting in the nearby Korle Lagoon. Residents infilled the lagoon – packing the banks with car chassis, refuse, and sawdust – to create space for additional housing, which in turn led to flooding that spread fecal matter to the nearby Agbogbloshie market, the largest green market in the city. This cycle led to frequent outbreaks of cholera that spread throughout the country, resulting in hundreds of deaths. By 2015, when the research director for this project identified stakeholders who selected Old Fadama as a complex challenge they would like to address, the slum – which was locally known as “Sodom and Gomorrah” – was a government “no-go zone” due to the generally lawless environment.

Figure 1 Old Fadama informal settlement, May 2017

In the words of the director of public health (2007–2016) of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA, the mayor’s office), Simpson A. Boateng, MD:

Sodom and Gomorrah was not meant for human habitation, and all attempts to remove the people failed. It was an unorganized community; for example, there were no sanitation facilities, and there were illegal electrical connections that were fire hazards. I wanted to enter the cross-sector collaboration to help improve the conditions and standard of living. And there was a need to collaborate effectively with the community in order to achieve something. The project provided an environment for the Ghana Health Service, judiciary, police, and other stakeholders to meet so that we could discuss the problems that were confronted.

My main priorities were to make sure every individual felt safe, physically and mentally. The public health department was set up to support public health in Accra by protecting the environment, food safety, making sure the food vendors were clean and making safe food for people, and ensuring sanitation policies by making sure everyone had a toilet in their home. Lack of toilets is a major problem and results in people defecating into plastic bags and throwing them into the streets and nearby river.

In February 2015, Boateng was frustrated by the repeated cholera crises that began in Old Fadama and swept throughout the city and the country. When approached by the research director for this project, he leaped at the opportunity to create a cross-sector collaboration with the community.

Grand challenges require grand strategies. In cases such as Old Fadama, no one sector – including government – can address the complex development challenges. Complex challenges are largely social, affecting many people, systems, and sectors (Reference Rittel and WebberRittel & Webber, 1973). They can seem difficult or impossible to resolve, and typical top-down intervention strategies are not sufficient. Cross-sector collaboration, incorporating multiple stakeholders and viewpoints, is necessary to create effective solutions.

Cross-sector collaboration occurs when governments, nongovernmental organizations, communities, and citizens come together to achieve more than they could if they worked alone (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006). These diverse entities must collaborate effectively to impact complex challenges. In the United States and Europe, collaboration research has expanded dramatically over the past fifteen years, improving the practice and the way Western governments function (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). There are many well-developed examples of how the evidence base has been woven into the fabric of developed-country governance.

In low- and middle-income countries, many international development projects involve complex challenges, with multiple stakeholders representing various, sometimes competing, interests (Reference KritzKritz, 2018). However, collaboration research is not widely conducted, and in practice, governments and international development programs have not effectively adopted collaboration tools. Consequently, complex challenges in developing countries are being addressed without the advances of this new, yet robust, field. Development researchers agree that rigorous approaches to development are badly needed (e.g., Reference OstromOstrom, 2014). This Element reports such a rigorous project – an exploratory project, created in 2015 to respond to the critical evidence gap around cross-sector collaboration. The research director’s goal was to develop an evidence-based, stakeholder-driven participatory action research (PAR) intervention that resolved complex challenges in Old Fadama, could be evaluated at the process level, and had the potential to be scaled up sustainably. The intervention was subsequently piloted in 2018–2019 and replicated in 2020–2022.

In PAR, researchers and participants work together to define problems and formulate research questions and solutions (Reference Cornwall and JewkesCornwall & Jewkes, 1995). This research method couples knowledge generation – such as would occur in traditional research – with an additional component: a process to create or support organizational action and change (Reference Cornwall and JewkesCornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Reference Greenwood and LevinGreenwood & Levin, 1998). Counter to the typical international development approach, in the concept phase this PAR project required the stakeholders to resource their own participation and make all the strategy decisions by consensus, including where to work and what projects to undertake: to create their own solutions for the problems they wanted to resolve. For this project, the term “stakeholders” is used to mean the local group of research participants and others (who were not research participants, usually because the research team believed saturation was reached) who saw themselves as people who had a “stake” in resolving the challenge Old Fadama was facing. With this novel approach, the initial research questions included the following:

1. Would stakeholders around a complex challenge in Ghana build a cross-sector collaboration, if invited to do so (but not provided the resources to do so, other than a facilitator and a research director to help them)?

a. What would the stakeholders need from a facilitator?

b. What was the role of the research director (who was not providing resources or making decisions about the direction of the project)?

2. How would the stakeholders identify a challenge?

a. Which stakeholders would be involved in that decision making? Why?

b. What kind of challenge would they choose (e.g., would they choose “low-hanging fruit” or would they choose to work on something more difficult)?

3. Would the stakeholders expand the collaboration? And if so, how?

a. Would the stakeholders contribute resources to the collaboration? And if so, what?

b. Would the stakeholders take actions to resolve the challenge they identified? And if so, who would take them? What actions would they take?

When the research director for this project approached Boateng, he immediately saw the potential that this kind of research might improve his office’s results in Old Fadama. The Old Fadama collaboration began with three research participants: Boateng; his officer-in-charge for Old Fadama, Imoro Toyibu; and Sr. Matilda Sorkpor, HDR, a Ghanaian Catholic sister who worked to build a bridge between the government and the community. Peter Batsa, a researcher and project manager for the National Catholic Health Service, was engaged as a facilitator and to collect data on the project. Boateng described the beginning as follows:

We were able to start approaching the community by involving a community health officer, Imoro Toyibu. He was from the Sodom and Gomorrah community and trained in environmental health in northern Ghana. I had just hired him … and I was excited to have a link into the community. He led us into the community and convinced the people (because he was one of them) to enter into conversations with the government [and this project’s research director].

The project had the full political support of the former mayor and current mayor, as well as the new Minister of Sanitation. The Sodom and Gomorrah community was fierce and violent and did not trust the government at all; it was a no-go area. This is because the government made a lot of promises that were not fulfilled. The people also felt insecure because they thought the government was bent on getting them out of the area they occupied.

In June 2015, heavy flooding that killed hundreds of people in Accra was attributed to Old Fadama, and the AMA bulldozed the portion of the settlement that was encroaching on the river. The media captured images of violence and signs such as “Before 2016 You’ll See ‘Buku Harm’ [Boko Haram] In Ghana.” Residents rioted in response to having their homes demolished. In July 2015, the AMA hosted the first meeting with community leaders, facilitated by Batsa. As Boateng described:

We had a meeting in my office with Imoro, the Catholic Sisters, and the community leaders. This first meeting was very tense, but, gradually, they have become our friends. Normally, the AMA would make a decision and impose it on the people. The cross-sector collaborations approach involved everybody and made them part of the decision-making process; therefore, they see it as their own. And the government showed good faith and inclusiveness by coming to the meetings and discussing the projects with the community. That is one reason why this project is working.

Also, including the Catholic Sisters helped because they are respected and are seen as leaders. As I’ve mentioned, the community had a high level of mistrust of the government, but including the Catholics and involving the community in the initiative allowed for an effective collaboration. And it is working very well.

Partners in government agencies.

Video available at www.cambridge.org/Kritz_2nd_edition

From the beginning, the stakeholders expressed their frustration with short-term international development interventions that took time and resources from the community, but “nothing changed.” They shared a different perspective that cut across technical sectors. They took a challenge-focused approach, and their goal was to address the root cause of the challenges facing the settlement. In this heavily conflicted environment, with the fear of AMA bulldozers, a government policy against slum upgrading, and ongoing resettlement efforts that led to violence, the early stakeholders exhibited significant courage in joining this research study.

The PAR proceeded as follows: the research director introduced the concept of cross-sector collaboration and trained Batsa on the evidence base and how to serve as facilitator. They were the research team and worked with the initial research participants in a purposive, consensus-based process to expand the collaboration. In an iterative process, the research team continued to introduce the concept of cross-sector collaboration and educate the stakeholders about the existing evidence. The stakeholders used the evidence to inform their decision making – either to validate their decisions or, when they departed from the evidence base, as a prompt to explain to the research team why they were doing so. This PAR process created a “stakeholder platform,” a forum for discussions between different stakeholders to identify and prioritize community issues and develop solutions (Figure 2). The PAR process taught participants to stand in the shoes of others, learn from one another, develop a shared understanding of the challenge, and work together.

Figure 2 Stakeholder meeting

As the collaboration took shape, the PAR process continuously expanded the number of participants. The process allowed government officials to interface with the chiefs – the tribal elders – of sixteen tribes of Old Fadama. Through a series of focus group discussions (FGDs), the research participants identified numerous priorities: sanitation, community violence, the need to support vulnerable populations of kayayei women who carry goods in the markets (typically balanced on their heads), solid waste management, and a clinic. Their first priority, sanitation, led to a sanitation strategy and latrine and bathhouse project.

A local Catholic sister, Sr. Rita Ann Kusi, HDR, joined the research team as community liaison, and she and Batsa worked with community leaders (chiefs and others) to conduct a community survey of fifty-nine research participants to expand the community stakeholders and design a public latrine and bathhouse project. The latrine and bathhouse installation created a local policy change, and this is where the results became surprising: local sanitation businesses learned of the project, saw it as workable, and wanted to participate in the policy change. On their own initiative and with their own resources, the businesses began to install latrines and bathhouses in Old Fadama, creating a path to local sustainability and freeing the stakeholders to address the next priorities, creating new strategies and projects.

This Element describes in detail how the PAR process expanded the number of stakeholders from three to three hundred research participants. The initial results are consolidated into a PAR intervention that incorporates results from the process as well as the stakeholders’ first strategy, sanitation, and project, latrine and bathhouse installation. The Element then describes how the PAR process was replicated multiple times, creating novel results on a low budget and presenting new avenues for resolving complex challenges in Ghana. This Element is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the robust field of cross-sector collaboration in developed countries, and the nascent evidence from developing countries. This section highlights and synthesizes the evidence to explain the interdisciplinary research approach to create a model for addressing complex challenges – the challenges of Old Fadama – at their root cause.

Section 3 contains the research context, including a brief historical, political, environmental, and social description of Old Fadama. The PAR methods and results of each PAR phase are described in detail.

Section 4 presents a flowchart of the PAR intervention and an evaluation of PAR as a tool for creating and supporting cross-sector collaboration. The section also explains how the latrine installation project shaped the collaboration process.

Section 5 discusses the continued work of the collaboration, 2018–2022. Stakeholder decision making about the additional priorities (community violence, solid waste management, and a clinic) was used to refine the PAR intervention and plan network analysis.

Section 6, the Conclusion, describes the theoretical and policy significance of this project, and how the process will be further scaled with government support.

2 Why Cross-sector Collaboration?

Cross-sector collaboration occurs when governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), communities, and citizens come together to achieve more than they could if they worked alone (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006). Challenging to research and practice, this sort of collaboration is recommended when there is a clear advantage to be gained, for example, when complex challenges have defeated sectoral efforts (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). In 2015, the Old Fadama informal settlement of Accra presented just such an environment. Boateng had already identified many sectoral international development projects that had failed. Waste-picking machines installed by an international NGO at the nearby e-waste dump were unused (see Figure 3). Repeated cholera outbreaks were traced to the slum. Large infrastructure development projects in northern Ghana failed to attract Old Fadama residents back to their homes and communities of origin. Boateng attributed these failures to the fact that they were all sectoral approaches. The cholera epidemic was a driving force for the stakeholders to take a new approach: to create a process for addressing Old Fadama’s complex challenges at their root.

Figure 3 View of Old Fadama and municipal and e-waste dump

2.1 Complex Challenges

In the United States and Europe, the study of complex challenges began in the 1970s, when they were characterized as “wicked problems” (Reference Rittel and WebberRittel & Webber, 1973). These challenges are recognizable by their seemingly contradictory requirements, with complex interdependencies that take significant time and sustained effort even to define. Reference Rittel and WebberRittel and Webber (1973) transformed the thinking with the idea that a formulation of these kinds of problems was, necessarily, the solution to these problems, because the solution creation is what leads to definition. The leadership literature describes complex challenges as “adaptive” – because of their complexity, stakeholders may not only perceive the solutions differently but may even have difficulty agreeing on the problem (Reference HeifetzHeifetz, 1994).

By contrast, Reference Rittel and WebberRittel and Webber (1973) identified “tame” challenges as those that a manager, who had the right education and competencies, could understand and solve through a formulaic process. The leadership literature calls these “technical” challenges, those that groups or a technical community would perceive and tend to design a solution the same way (Reference HeifetzHeifetz, 1994).

According to Rittel and Webber and Heifetz, understanding complex challenges comes through a deep knowledge of context, and the context is used to give the problem scope and to understand what solutions are possible. Solutions are best identified according to individual and group interests, values, and ideologies through a process involving multiple parties who are equipped, interested, and able to create the solutions.

2.2 Cross-sector Collaboration

The study of complex challenges evolved into the study of cross-sector collaboration. This new field began to develop rapidly in 2006, aided by an important literature review by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone that coalesced the fragmentary evidence from many disciplines into a picture catapulting the research funding and interest at the municipal, state, and federal levels in the United States. They defined cross-sector collaboration as “the linking or sharing of information, resources, activities, and capabilities by organizations in two or more sectors to achieve jointly an outcome that could not be achieved by organizations in one sector separately” (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006, p. 44). They structured their review around a number of “propositions” that they constructed based on their own research, weaving the nascent evidence from multiple fields into a picture that was accessible to both researchers and practitioners.

In 2015, this team published an updated review explaining the evolution of the field and how this research and practice, although challenging, vastly improved the way that governments – and other collaborating partners – respond to public challenges in developed countries (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). They identified seven holistic theoretical frameworks created in the prior ten years and honed important concepts, such as design, strategic management, and governance, that had come about during that time. Elaborating on the theme that diverse entities must collaborate effectively to impact and ultimately resolve complex challenges, the review identified a number of important areas for future research focus.

Even though their review specifically excluded developing-country evidence, looking at the developed-country progress offers new avenues for thinking about how to implement the research and practice of cross-sector collaboration in developing countries. However, even with such a comprehensive and inspiring review as a starting point, when this project began, it was difficult to see how the results could be applied in Ghana. For example, one influential case study, used to advance the theory and practice, involved a $1.1 billion demonstration project to reduce congestion on an urban transportation corridor in Minneapolis, Minnesota (Reference Bryson, Crosby, Stone, Saunoi-Sandgren and ImbodenBryson et al., 2011b). This funding implies a level of infrastructure and human resources that does not exist in developing countries. This resource disparity explains why it is challenging to apply the collaboration literature in developing countries and points to, perhaps, why development industry norms have not yet evolved to incorporate collaboration best practices.

2.3 Development as Usual

Debate among critics and proponents of international development funding has been focused on whether, or the extent to which, international aid funding and development programs should exist (Reference Flint and zu NatrupFlint & zu Natrup, 2019). Critical works such as Damisa Moyo’s Dead Aid demand an end to aid, arguing that it exacerbates poverty (Reference MoyoMoyo, 2010). Academic Jeffrey Sachs champions the other side of the debate in The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time – that aid can transform developing economies (Reference SachsSachs, 2006). Some argue development programs should exist but adapt, taking into account evidence from social capital theory (Reference Woolcock and NarayanWoolcock & Narayan, 2000). Others advocate reducing overall aid and point to alternatives like social entrepreneurship and civic innovation (Reference FowlerFowler, 2000). The debate continues, with general agreement that current aid-funded programs do not achieve desired results, and vast improvements are needed if these systems are to end poverty (Reference EasterlyEasterly, 2008). This project started with the premise that international development programs lack efficacy and fail to become sustainable because international development funding mechanisms and projects do not take into account the evidence base on how to resolve complex challenges.

While international development models call for work across sectors, development agencies – and therefore their grantees, including researchers and practitioners – have not yet adapted to incorporating best practices from cross-sector collaboration literature and cases. Virtually every development funding agency operates with a sectoral approach, requiring proposals around predetermined issues and preferencing predesigned projects with established metrics. These factors fail to account for the human relationships (Reference EybenEyben, 2010) and conflicts that must be worked through to resolve complex challenges. Thus, complex challenges are not – and cannot be – addressed effectively.

Few, if any, funders offer the flexibility of a stakeholder-driven, strategic approach that is suitable for actually resolving complex challenges. Compounding this issue, funders hinder the time-consuming process of creating sustainable solutions by imposing short timelines for reporting results (Reference Airing and TeegardenAiring & Teegarden, 2012). Thus, when development researchers or practitioners try to address complex challenges and at the same time attempt to complete their predefined program of work within a standard three- or five-year funding cycle, they run into the issue of deadlines. How would one manage the relationships and the necessary conflict that arise in the resolution of these challenges? It is not possible. Instead, the researchers and practitioners try to “tame” the “wicked” problems (to use Rittel’s and Webber’s language), defaulting to outdated evidence as they treat these problems as standard projects. This approach is designed to fail.

Alternatively, they may try to conduct evidence-based cross-sector collaboration, but on a shortened timeline, thus resorting to practices that are rigid, lack rigor, and misapply or do not use current evidence. In the implementation literature, this is called “rival framing”; for purposes of this discussion, it means that performance measurements and donor reports distort the activity – the work of collaboration – to comply with desired new collaboration norms (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). In one glaring example, dozens of articles touted the efficacy of a major international collaboration with the laudable goal of treating and preventing HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Yet, when local stakeholders were later interviewed, researchers discovered that the Dutch project leader worked extensively in South Africa but lacked cultural competence in Botswana. The top-down approach did not readily incorporate practices that would work locally, and project results were prioritized over relationships. It took several years for the project to achieve some “mutuality” so that local government leaders believed they were valued partners (Reference Ramiah and ReichRamiah & Reich, 2006). These issues were compounded by enormous external pressure due to short funding timelines.

Cross-sector collaboration research is needed to improve these sorts of international development programs. A more robust, contextually relevant evidence base could identify collectivist cultures that are more suited to collaboration, available resources, personnel, government structures, key jobs for international and donor organizations, and many other opportunities. This research would strengthen relationships and ultimately improve program results. This project was developed in part to address these issues.

2.4 Cross-sector Collaboration Evidence in Developing Countries

This research began with a literature review of the developing-country cross-sector collaboration evidence. The goals of the review were to find out how collaboration research was conducted in developing countries and to identify collaboration interventions that could be used as a model for Old Fadama.

The literature search began with health literature, which is robust and particularly well organized. A broadly constructed search identified 20,000 articles mentioning collaboration-related topics in their title or abstract. However, only 165 articles contained data on how cross-sector collaboration was implemented, and just a handful of those articles included rigorous study of the collaboration itself (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). Because of the lack of evidence, the review then incorporated an extensive hand search in a number of other fields, yielding little additional data. Thus, the most important outcome from the review was to illustrate how little rigorous collaboration process research has been done in developing countries.

Nonetheless, the results, described in Figure 4 were interesting in that they explained how contextual factors differed in developing countries, while generally mirroring the developed-country theory. Thus, the results related to how to construct collaboration process were organized around the Bryson, Crosby, and Stone team’s themes of design, strategic management, and governance (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006, Reference Bryson, Crosby and Stone2015; Reference Stone, Crosby, Bryson, Cornforth and BrownStone, Crosby, & Bryson, 2013).

Figure 4 Systematic review model

Analyzing the results of the review combined theoretical understanding and empirical evidence and focused on explaining the relationship between the context, mechanisms, and outcomes (Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and WalshePawson et al., 2005). Regarding how to conduct the collaboration research, the small number of research studies that were deemed to be rigorous had several commonalities that were used to construct this project (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). The studies (1) used mixed methodology including interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, and observation; (2) incorporated a high degree of contextual complexity into the research design; (3) involved multi-level participation in the research, including nongovernmental organizations, grassroots community organizing, and government offices; and (4) captured mechanisms, the often-unstated emotional reactions activated by the cross-sector collaboration intervention (Reference Ahmed and AliAhmed & Ali, 2006; Reference Campbell, Nair and MaimaneCampbell, Nair, & Maimane, 2007; Reference Manning and RoesslerManning & Roessler, 2014; Reference Pridmore, Carr-Hill and Amuyunzu-NyamongoPridmore et al., 2015; Reference Sanchez, Perez and CruzSanchez et al., 2009). Because of the limited developing-country evidence, both the developed-country evidence base and the systematic review were used to establish the previous evidence base and the collaboration principles that undergirded the PAR process.

2.5 Collaboration Principles

Rittel and Webber explain how “the analyst’s ‘world view’ is the strongest determining factor in explaining a discrepancy and, therefore, in resolving a wicked problem” (Reference Rittel and WebberRittel & Webber, 1973, p. 166). With that said, it is important to understand the “world view” – the collaboration principles – that undergirded this research. At the beginning, these were not clearly articulated ideas but rather areas where a stakeholder-driven approach, informed by the evidence, with data collected based on the stakeholders’ decision making, might advance the existing evidence. Some of these principles did not work (and are not discussed in this Element). Those described in Sections 2.5.2–2.5.8 (see Figure 5) became part of the PAR intervention results (see Figure 10).

1. Asking stakeholders to identify something they were not able to do within their own sector will lead to identification of a complex challenge.

2. Through cross-sector collaboration, a facilitator can create a value-neutral understanding of the conflict between the government and the community and work develop a shared understanding. With shared understanding, complex challenges become a series of technical challenges for which the stakeholders can work as a “technical” team to design solutions.

3. “Middle-out” collaboration is necessary when there is a conflicted relationship between government and community stakeholders, and neither is positioned to develop the most effective strategic response to complex challenges.

4. Emergent design and governance — characterized by stakeholders making strategic choices about research methodology, participant selection, context, and projects — will build a strong PAR process.

5. Stakeholders that resource their own participation will have “buy-in,” and be more committed to a long-term collaboration process.

6. A process and projects resourced by local stakeholders will build sustainability.

7. Facilitation of consensus through the PAR process provides rigor necessary for collaboration around a complex challenge.

Figure 5 Collaboration principles

2.5.1 Identifying a Complex Challenge

In their first review of the evidence, Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006, p. 45) looked at the factors preceding cross-sector collaboration and explained two ways that organizations go about pursuing it:

On one hand, our own view is that organizational participants in effective cross-sector collaborations typically have to fail into their role in the collaboration. In other words, organizations will only collaborate when they cannot get what they want without collaborating. The second response is to assume that collaboration is the Holy Grail of solutions and always best. Often, governments and foundations insist that funding recipients collaborate, even if they have little evidence that it will work. [internal citations omitted]

These two characterizations are consistent with the findings from the literature review for this project (Reference KritzKritz, 2017, Reference Kritz2018). The developed-country evidence now offers a number of ways to assess the need for, and potential efficacy of, a cross-sector collaboration, which is recommended when there is a clear advantage to be gained – for example, when there is sector failure (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006, Reference Bryson, Crosby and Stone2015). However, in a developing-country setting, where technical sectors are not as strong and indicators can vary widely based on the population, geography, and other factors, it was not clear how to identify sector failure.

In this project, the research director asked the initial stakeholders from multiple sectors, Boateng, Sr. Matilda, and Imoro Toyibu, to identify a challenge that they were not able to address on their own to identify a true complex challenge and sector failure. They identified Old Fadama as the challenge that they wanted to address. However, because urban slums are such a pervasive and growing issue, it was not clear whether any slum would be perceived as sector failure – perhaps these were environments where each sector could point to another that had failed. Or, perhaps slums had replaced rural areas as the “end of the road,” areas the government needed to address, to take a next step in providing services, but not necessarily perceived as failures.

However, Old Fadama stood out for one particular reason: multiple times per year, cholera epidemics began in the slum and swept throughout the country. The local government received constant negative local media attention, and more recent epidemics were reported in the international media, worrying high-level government officials that the reports would have a negative effect on tourism and the choice of Ghana as a venue for hosting international meetings. The director of public health documented how similar efforts combatted cholera in other slums but did not work in Old Fadama. He perceived these repeated epidemics as reflecting sector failure.

2.5.2 Creating Shared Understanding

Cross-sector collaboration creates shared understanding of complex challenges (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015), but it is not an easy task to create shared understanding in a high-conflict environment such as Old Fadama. This context requires a conflict-sensitive approach (Reference AndersonAnderson, 1999; World Health Organization, 2019). Conflict can be value neutral and is important in that it surfaces issues that need to be addressed for those in conflict to begin to collaborate (Reference CarpenterCarpenter, 2019). However, these conflicts need to be handled with care to achieve solutions (Reference BinghamBingham, 2009). The PAR interviews were used in part to infuse the process with references to local culture and values regarding the importance of working together, respecting others, and seeking understanding across divisions. The research team used the PAR process to build on these norms and create a shared understanding of Old Fadama’s challenges. To do so, the facilitator focused on the stakeholders’ shared interests rather than their “positions,” by identifying each stakeholder’s basic human and organizational needs and focusing attention on doing the best “for Mother Ghana” (see Figure 6). Thus, the PAR process was used to create a value-neutral understanding of the conflict between the government and the community, which provided the opportunity to develop a shared understanding of the challenges.

Figure 6 Old Fadama community meeting

These norms have further developed and include both a shared terminology and a value system based on mutual respect and understanding (Reference Thomson and PerryThomson & Perry, 2006). As the norms grew, new stakeholders were able to more rapidly expand their perspective, understand the PAR process, share their ideas, and see these ideas incorporated, because of the shared understanding of and language around Old Fadama’s challenges.

2.5.3 Middle-out Collaboration

In developing countries, cross-sector collaboration often works “top-down” consistent with the flow of development aid funding, or “bottom-up,” through work with communities (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). These processes are anchored in powerful constituencies that help to orient the work. Because of the conflicted relationship between the municipal government and Old Fadama, neither government nor community was positioned to lead the other. An organization was needed to bridge this divide, and the research director created the term “middle-out collaboration” to define this leadership role.

If government does not mandate cross-sector collaboration, the literature suggests starting with a small group of stakeholders and expanding the collaboration as the momentum grows (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). This approach requires strategic relationship building (Reference Magrab, Raper, Blau and MagrabMagrab & Raper, 2010). The research director designed the middle-out stakeholder identification to determine those organizations best positioned to bridge the divide around Old Fadama. Catholic sisters – because of their moral leadership, demonstrated capacity to work with communities and reputation for long-term commitment to fill gaps in government social service delivery – were enrolled as research participants to sit in the “middle” and build a bridge “out” between government and the community.

2.5.4 Emergent Design and Governance

The collaboration literature describes a range of design and governance possibilities from formal structures to informal interactions through which decisions can be made (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006; Reference Provan and MilwardProvan & Milward, 1995; Reference Stone, Crosby, Bryson, Cornforth and BrownStone, Crosby, & Bryson, 2013). Employing deliberate, formal design and governance in the context of already planned interventions is consistent with the literature on developing-country collaborative projects (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). By contrast, emergent design allows missions, goals, roles, and action steps to emerge over time within a network of involved or affected parties to overcome problems in a system (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015).

Leading journals identify a significant research gap around public participation in developing countries. When the gap is viewed from the field of psychology, it is clear that this sort of participation requires both processes and readiness of those whose participation is sought (Reference MoghaddamMoghaddam, 2016). Ideally, a citizen must be guided by a critical and open mind, while government must accept and respond to appropriate criticism. Emergent design addressed both the readiness of the governing (city government and slum leadership) and the governed (slum leadership and residents) to participate in a more transparent process that evolved to meet their needs at the same time (Reference Kritz and MoghaddamKritz & Moghaddam, 2018).

Because Old Fadama was an informal settlement that developed on land set aside as an eco-zone or preserve, government infrastructure planning did not include that geographic area. Civil servants were unable to take up the challenge of infrastructure planning for a variety of reasons. For example, the government created its budgets around city planning maps that did not include the settlement, so creating a budget for slum improvement would require changing the city plan. More immediately, solid waste pickup or installing water pipes and sanitation required creating road access, which would displace residents with nowhere else to go.

More recent scholarship explains how informal norms of settlement and belonging – specifically the interaction between indigenous landowners and migrants – structure everyday politics and spill over into formal elections (Reference PallerPaller, 2019). Because the slum contained a large population of voters with ties throughout the country, politicians were wary about angering the community. Politicians had historically made promises about slum upgrading, but these promises had not been kept. Slum leadership resorted to leveraging media attention to demand dialogue with the government and advocate for better infrastructure, but this only created more tension and led to at least one failed infrastructure project.

Conflict is value neutral; if managed productively, it can be used as an opportunity to galvanize stakeholders to try different solutions (Reference CarpenterCarpenter, 2019). However, learning to use conflict productively takes time. Emergent design and governance, where stakeholders make strategic choices about research methodology, participants, context, and projects allowed stakeholders time to learn to work through their conflicts, thus building a strong PAR process.

2.5.5 Creating “Buy-In”

The evidence from psychology suggested that stakeholders’ investment in various projects would increase their likelihood of continuing to participate, thus strengthening their bonds to the projects (Reference FestingerFestinger, 1962). Thus, to increase stakeholder commitment or buy-in, the collaboration principle was that the stakeholders must find the necessary human and physical resources for their own participation and projects. Previously, the stakeholders were accustomed to development projects, funded by northern governments and international donor organizations, that supported all local participation and project costs. The idea of resourcing their own participation and projects challenged their thinking in a positive way. Early in this project, consistent with old expectations the international development projects created, stakeholders made numerous requests for payments and asked for laptops, smart phones, and other tools. Over time, however, these requests diminished. As the facilitator introduced the project to new stakeholders, he explained that the project was a “public good” being done “for Mother Ghana,” so “we all should put in our own resources.” As new stakeholders “bought in” to this shared vision, they did so with the understanding that they would be developing projects based on the resources at their disposal or that they raised together.

2.5.6 Building for Sustainability

A growing body of research offers perspective on process-oriented studies such as this one (Reference Brownson, Colditz and ProctorBrownson, Colditz, & Proctor, 2012; Reference Peters, Adam, Alonge, Agyepong and TranPeters et al., 2013; Reference SpiegelmanSpiegelman, 2016). However, implementation of sustainable projects in developing countries has proven to be challenging, despite the focus on this concept (Reference Gruen, Elliott and NolanGruen et al., 2008; Reference Shediac-Rizkallah and BoneShediac-Rizkallah & Bone, 1998). A frequently documented challenge is that when northern international development funding ends, the projects stop working, thus erasing the supposed gains from the effort. One factor of this issue is that the international development funding drove the project. Stakeholders resourcing of their own participation through all phases of a project is one key to sustainability (Reference FowlerFowler, 2001). For this PAR project, the principle was that if the stakeholders resourced their own participation, the process would be created with local funds, building toward sustainability.

2.5.7 Requiring Consensus

Collaborative governance is an explicit strategy for incorporating stakeholders into government policy and planning through “multilateral and consensus-oriented decision processes” (Ansell & Gash, 2008, p. 548). Collaboration requires a commitment to process that goes beyond the initial design (Reference Bryson, Crosby, Stone and Saunoi-SandgrenBryson et al., 2011a; Reference Mintzberg, Ahlstrand and LampelMintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, 1998). The research director trained the local facilitator on the collaboration evidence and together they began to develop the PAR process. The evidence suggests that these kinds of “bridging social capital” roles are one important facet of development (Reference CarpenterCarpenter, 2019; Reference Woolcock and NarayanWoolcock & Narayan, 2000). The research director, facilitator, and community liaison (the research team) collected all data and engaged the stakeholders through interviews, focus groups, a survey, and continuous data collection and triangulation. Throughout the PAR process, the research team used the cross-sector collaboration evidence base as a guide, to support the PAR process, educate the stakeholders, and inform their decision making. The principle was that a consensus-based PAR process would provide a level of rigor suitable for collaboration around a complex challenge.

2.5.8 Application of the Collaboration Principles

The research director introduced the concept of cross-sector collaboration at the outset of the project. The research team educated the stakeholders about the developed- and developing-country evidence base; supported the stakeholders through PAR in forming a cross-sector collaboration; and developed priorities, strategies, and projects with the stakeholders. This process generated the data that the research team collected, analyzed, and shared with the stakeholders so that they could understand their own decision making. Utilizing grounded theory helped to make sense of the data and to develop a theoretical account of the process. The social sciences employ grounded theory as an “inductive, theory discovery methodology that allows a researcher to develop a theoretical account of the general features of a topic while simultaneously, grounding the account in empirical observations or data” (Reference Martin and TurnerMartin & Turner, 1986, p. 141). Section 3 describes how the PAR process unfolded, and the role of these collaboration principles in expanding the process.

3 The Accra Stakeholder Platform: Designing a Cross-sector Collaboration Intervention

Rapid urban migration, leading to the growth of urban slums, is a worldwide phenomenon. Africa has been urbanizing at a rate of 3.5 percent per year during the past two decades, a rate that is expected to continue until 2050 (African Development Bank Group, 2012). In Ghana, migration to urban areas coupled with a severe housing shortage has given rise to rapidly growing slums (Reference PallerPaller, 2015). Hundreds of thousands of people have flooded the cities seeking liberation from increasingly difficult lives. As of 2014, an estimated 37.9 percent of Ghana’s urban dwellers (United Nations Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014a) or 5,349,300 people lived in slums (United Nations Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014b).

The United Nations Human Settlement Program defines slums by physical conditions including lack of durable and permanent housing, sufficient living space, access to safe water and sanitation, and security of tenure that prevents forced evictions (United Nations Human Settlement Program, 2006). These conditions contribute to a multitude of development challenges, including high rates of environmental deterioration, poverty, and unemployment; high levels of conflict and gender-based violence; overcrowding; and poor sanitation and waste management. These complex challenges impact all sectors and often result in protracted and entrenched conflicts.

The research director’s initial goal for this project was to develop an evidence-based, stakeholder-driven PAR intervention to create cross-sector collaboration.Footnote 1 This meant that the research needed to incorporate analysis of the PAR process, as well as the way that any projects shaped it. Additional goals that were developed through the PAR process, with the facilitator, community liaison, and stakeholders, were that the collaboration should work to resolve complex challenges in Old Fadama and that the PAR process had the potential to be scaled up sustainably. See Figure 7 for definitions of this terminology.

1. Evidence-based means that, throughout the process, the stakeholders were informed of the developed- and developing-country evidence, were given an opportunity to reflect on the options presented by the evidence base and the situation they were evaluating, and made decisions that they understood were consistent with the evidence base or departed from the evidence base.

2. Stakeholders are those who are engaged in cross-sector collaboration, providing time or resources to resolve a challenge. The Old Fadama stakeholders call their form of organization their “collaboration” or “stakeholder platform.” Research participants are stakeholders who participated in formal data collection; some stakeholders did not participate in formal data collection, usually because the research team felt the process reached saturation.

3. Stakeholder-driven means that the stakeholders selected the location and focus of the study and made all strategy and project decisions including stakeholders to involve, projects to undertake, and when to move to the next stage of the process. When this Element describes how the stakeholders or “the collaboration” took an action, that means that all research participants — who make up the collaboration — reached consensus on that course of action and those taking the action were considered to be doing so on behalf of “the collaboration.”

4. Intervention means a package of collaboration principles and a PAR process to build cross-sector collaboration. The intervention was designed without a focus on one sector so the stakeholders could identify new challenges and create new strategies and projects to resolve them.

5. Analysis at the process management level means that data was collected in order to feed back into and strategically manage the collaboration. Evaluation at the project level means that projects needed to be analyzed as to their impact on the collaboration.

6. The facilitator, Mr. Peter N. Batsa was engaged to collect data and serve as the collaboration’s facilitator. His organization, National Catholic Health Service, was a research organization that brought significant planning and research skills to the process. They served as a bridging organization (Carpenter, 2019; Manning & Roessler, 2014), needed because of the conflicted relationship between the municipal government and the community. The facilitation literature describes this vital role as creating consultative meetings and platforms for discussion to build relationships and accountability between differently resourced organizations with different capacities (Kritz, 2017).

7. The community liaison, Sr. Rita Ann Kusi, HDR, of the Handmaids of the Divine Redeemer congregation of Catholic sisters, was engaged to collect data and serve as the collaboration’s community liaison. Her congregation served as a bridging organization (Carpenter, 2019; Manning & Roessler, 2014), needed because of the conflicted relationship between the municipal government and the community.

8. Resolved means that the stakeholders wanted to resolve challenges at the strategic level or root cause. “Social problems are never solved” (Rittel & Webber, 1973), so stakeholders’ programmatic solutions were developed based on strategy that they considered would lead to sustainability.

9. Complex challenges or adaptive challenges are largely social, affecting many different people, systems and sectors and generally defined through finding a solution to the problem itself (Rittel & Webber, 1973).

10. The Old Fadama community of Accra was the focus of this research study. In Phase I, the community was represented by a community member who worked for the municipal government. In Phase II, three community chiefs joined as research participants in the study. In Phase III, a community survey was used to engage a broader range of community members. Later in the process, all chiefs were involved in planning latrine installation.

11. Scale-up is the stakeholder-driven and locally resourced process of expanding the project according to the stakeholder needs and interests. Additional terms include adoption and replication, which are different methods of expanding a project.

12. Sustainable, for this project, is defined as when organizations refine their operations to incorporate cross-sector collaboration into their practices, projects address the root cause of the complex challenges the stakeholders choose to address, and human resources and project costs are resourced locally.

Figure 7 Definitions

Section 3.1 describes the research director’s exploratory research to identify initial stakeholders and a slum community. Section 3.2 begins with a discussion of PAR as a tool to create and strategically manage cross-sector collaboration. The research team used the PAR process to introduce the concept of cross-sector collaboration, educate the stakeholders about the existing evidence, and support them in forming a cross-sector collaboration. The research methods and development of the PAR phases are described in detail, including interviews, focus group discussions (FGD), and a community survey. Section 3.3 explains the piloting and results of the intervention components.

3.1 Exploratory Research to Identify Stakeholders and Community

This section explains in further detail the initial stakeholder identification described in Section 1. The research director began by identifying, in a purposive process, possible research participants who could work together to identify a challenge. Catholic sisters seemed to be the nongovernmental actors best-known in Ghana for making consistent, long-term commitments to poor and marginalized communities. The National Catholic Health Service identified a purposive sample of four sisters from congregations known for their work with the poor, who might want to participate. Congregations are religious organizations of sisters dedicated to social service in the world, rather than a monastic or cloistered way of life. There has been a concerted push in international development to engage faith organizations (Reference Duff and BuckinghamDuff & Buckingham, 2015). However, they are nearly absent from the collaboration literature, so it was unclear if the sisters would enroll (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). The research director interviewed them, and Sr. Matilda Sorkpor, HDR (the “lead sister”) agreed to participate and chose Old Fadama as a place she wanted to work but was hesitant to enter because the challenge was so great. In 2018–2019, she educated and enrolled several additional sisters from different congregations.

The municipal government seemed to be a logical partner because Old Fadama was an urban slum. When the research director contacted Boateng, the director of public health of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (the AMA, the mayor’s office), he responded with enthusiasm and relief:

Thank God you are here. We need help. Everything we have tried in this community seems to fail. I am meeting with the press again this morning about the cholera epidemic that originated there. We can’t find the solution to this problem on our own. I am willing to try anything.

Little is documented about effective government partnership in the scholarly literature, so it was unclear what to expect from government participation (Reference Barnes, Brown and HarmanBarnes, Brown, & Harman, 2016). Through interviews, representatives of the Department of Public Health shared that their typical efforts combatted cholera in other areas but did not work in Old Fadama. The evidence suggests that sectoral failure is an antecedent to cross-sector collaboration, and a facilitating organization can assist collaboration formation (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006). Consistent with that evidence, and because of the research focus and Catholic sisters’ engagement, Boateng and others from the Department of Public Health became enthusiastic partners. They supported community involvement and provided public and environmental health research to inform stakeholders’ decision making. Later, when the research participants undertook a latrine project, the Department of Public Health coordinated between AMA offices that scoped the latrines, developed plans, and provided resources for permits, beginning to change the city’s policy around Old Fadama slum improvement.

As described in Section 1, the Old Fadama community was represented by Imoro Toyibu, a resident who had served for years as its secretary and has recently been hired as the municipal government’s public health officer for Old Fadama. After the initial interviews, he identified several research participants, leaders from Old Fadama community organizations. These included the Kayayei Youth Association, a community association of women and girls locally known as “kayayei,” head porters who carry goods (typically balanced on their heads) in markets and sell products on the streets throughout Accra; and the Old Fadama Youth Development Association (OFADA), the Old Fadama community association governed by the chiefs (community elders, see Figure 8) of the sixteen tribes residing in Old Fadama. OFADA did not include the chiefs of the two warring tribes that many believed were responsible for much of the organized violence in the slum. However, the association represented the majority of Old Fadama residents. Those familiar with community-based approaches know that the idea of a community may “create the illusion that people in a particular location, neighborhood, or ethnic group, are necessarily cooperative, caring, and inclusive. The reality may be very different, as power differentials in gender, race, and class relations may result in exclusion, and threaten the apparent cohesiveness of the group in question” (Reference Mathie and CunninghamMathie & Cunningham, 2003, p. 475). Consistent with the evidence, Old Fadama was not homogeneous, and decision making and negotiation often took place along tribal lines (Reference PallerPaller, 2014). A number of other community leaders and members also enrolled as research participants to offer their input on strategy and projects.

Figure 8 Old Fadama community elder

Two National Catholic Health Service (NCHS) officers served as the Ghana-based facilitation and research team. NCHS is a local organization, an association of Catholic health institutions that provides research and planning services and coordinates with government health services. The director of NCHS provided early guidance on collaboration with sisters and identified a staff member, Peter Batsa, to collect data and serve as the collaboration’s facilitator. The facilitation literature describes this vital role as creating consultative meetings and platforms for discussion to build relationships and accountability between differently resourced organizations with different capacities (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). A number of case studies in the literature detail important facilitation skills and responsibilities. These include research (Reference Campbell, Nair and MaimaneCampbell, Nair, & Maimane, 2007; Reference Pridmore, Carr-Hill and Amuyunzu-NyamongoPridmore et al., 2015; Reference Sanchez, Perez and PérezSanchez et al., 2005), as well as catalyzing (Reference Saadé, Bateman and BendahmaneSaadé, Bateman, & Bendahmane, 2001), linking (Reference Kielmann, Datye, Pradhan and RanganKielmann et al., 2014), bridging (Reference Manning and RoesslerManning & Roessler, 2014), brokering (Reference Sablah, Klopp and SteinbergSablah et al., 2012) or serving as an intermediary (Reference Murthy, Frieden, Yazdani and HreshikeshMurthy et al., 2001; Reference Probandari, Utarini, Lindholm and HurtigProbandari et al., 2011), coordinating (Reference Brooke-Sumner, Lund and PetersenBrooke-Sumner, Lund, & Petersen, 2016; Reference Thaennin, Visuthismajarn and SutheravutThaennin, Visuthismajarn, & Sutheravut, 2012), convening (Reference Li, Huikuri, Zhang and ChenLi et al., 2015), and facilitating (Reference Manning and RoesslerManning & Roessler, 2014; Reference Rangan, Juvekar and RasalpurkarRangan et al., 2004; Reference WessellsWessells, 2015).

Due to the complexity of Old Fadama’s problems, all of these responsibilities were deemed essential. As the collaboration grew, a Catholic sister, Sr. Rita Ann Kusi, HDR, joined the research team to serve in the important role of community liaison. The data later showed that her presence conveyed the message that this was a nonpolitical, public interest effort, thus building trust in the community and differentiating this project from efforts to sway voters in the lead-up to the contentious 2016 national elections. Later in the project, she received a grant to build a block of latrines in partnership with the municipal government and with input from the Old Fadama community.

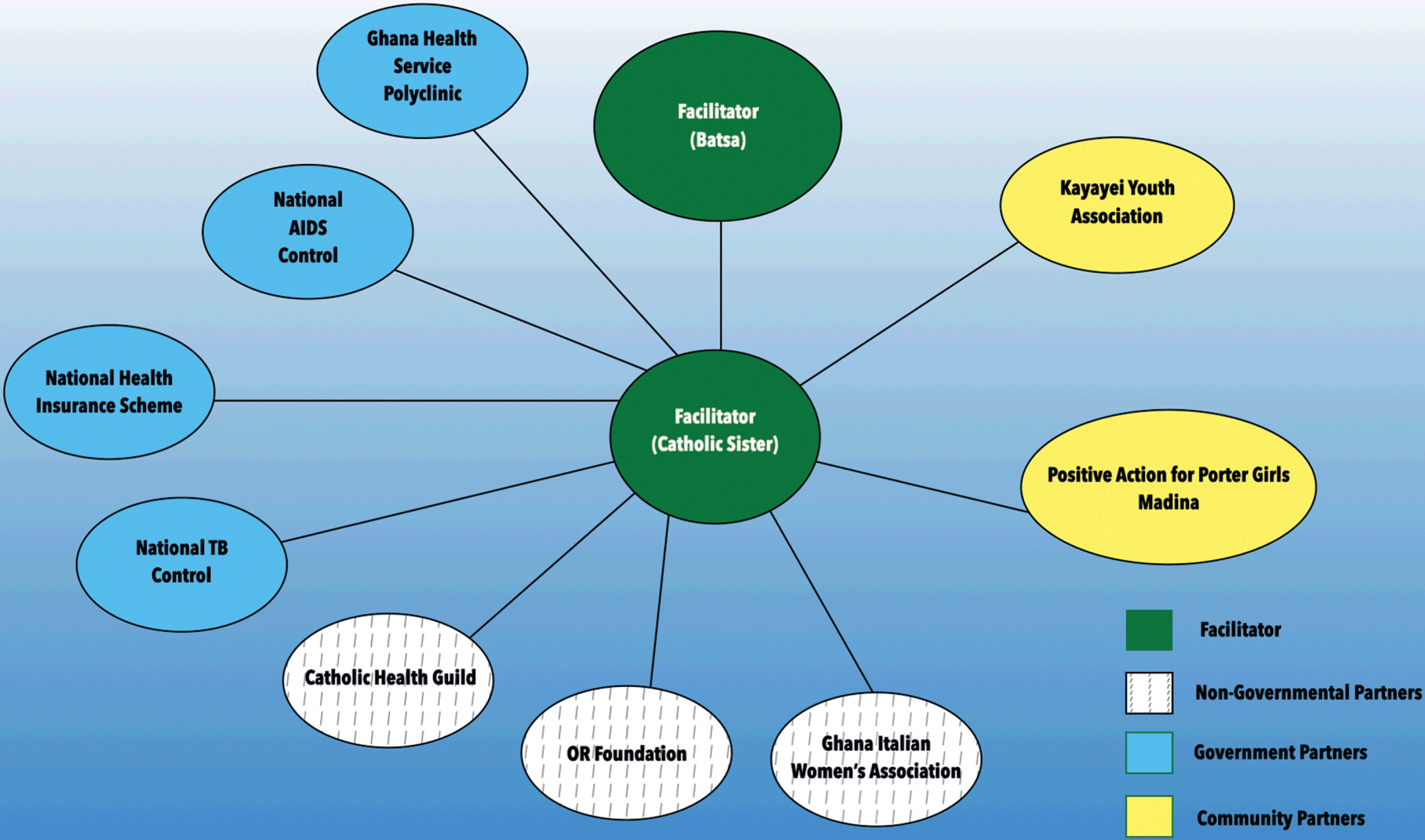

Each research participant informed and sought input from their own important constituencies – stakeholders within their own organizations as well as others. As examples, Boateng consulted the leadership of the Ga State, a politically powerful Accra group with a historic ownership interest in the Old Fadama land. NCHS and the sisters consulted the Ghana Catholic Bishops Conference and the Office of the Metropolitan Archbishop. These offices represent the hierarchy of the Catholic Church and supported the sisters’ work in a coordinated manner. In time, some constituents became stakeholders. For example, as the project progressed, Boateng liaised with the Ministry of Inner-City and Zongo Development and the Ghana Health Service, government ministries that offered their input and later became stakeholders when the community and municipal priorities aligned with their offices’ national planning goals. Figure 9 describes the research participants and their stakeholders (Ministry of Health, Archdiocese of Ghana, Ga State) who joined the collaboration between 2015, when it began, and 2017, the end of the concept phase.

Figure 9 Stakeholder diagram

3.2 Development of the Participatory Action Research (PAR) Intervention Components: Interviews, Focus Group Discussions (FGD), and a Community Survey

As described, the stakeholders began by identifying a challenge that they would like to try to address through cross-sector collaboration, using their own resources and applying for funding as needed. There were three PAR phases: (1) key informant interviews with Catholic sisters identified a location for the study, to which the municipal Department of Public Health agreed; (2) focus group discussions (FGDs) set community priorities, aligned them with the priorities of government planning, and created strategies and projects; and (3) a community survey increased community member participation and further defined project goals and measurement.

Participatory action research couples knowledge generation – such as would occur in traditional research – with an additional component: a process to create or support organizational action and change (Reference Cornwall and JewkesCornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Reference Greenwood and LevinGreenwood & Levin, 1998). PAR was identified as a methodology that could meet the stakeholders’ needs in a complex environment, including a rapidly evolving urban slum, a diffuse city agency, and multiple congregations of Catholic sisters that were taught to plan strategically and work together as they made the decision to move from better-served rural areas to an urban slum. PAR incorporates local priorities, processes, and perspectives (Reference Cornwall and JewkesCornwall & Jewkes, 1995). A PAR process involves researchers and participants working together to define the problem and formulate context-specific research questions and solutions. The research team and participants worked together to create the PAR process. They made joint decisions to establish the research agenda; collect and analyze data on stakeholders’ opinions; identify priorities, strategies, and projects; and incorporate the resulting knowledge into the PAR process.

These steps transformed each participating organizations’ practices in comparison with the way they worked in the past, and the way other similar organizations worked. The research team incorporated a holistic understanding of the context of each of the stakeholder organizations, including their structures and history with cross-sector collaboration, cultures, organizational norms, and strategies. Through the use of qualitative methods, the research team was able to understand the stakeholders’ organizations’ practices within their own contexts, why cross-sector collaboration was the tool they chose to employ, and where evidence could inform their decision making (Reference Cornwall and JewkesCornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Reference Miles, Huberman and SaldanaMiles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014).

Throughout the process, the research team used purposive sampling to select research participants based on their perspective and role (Reference StringerStringer, 1999), and intensity sampling based on the understanding of current information and the need to fill remaining gaps (Reference PattonPatton, 2015). The research team took participant observation notes at all interviews and focus groups, as well as during the survey and meetings. Most focus groups were audio recorded. The focus groups allowed the research team to observe stakeholder interactions within the context of their own organization and between organizations. As noted in the Figure 7, the terms “research participants” and “participants” are used to describe those who formally participated in data collection to inform the study. The term “stakeholders” is used to describe groups including participants as well as others who did not participate in formal data collection, usually because the process was believed to have achieved saturation. The methodology of the project included continuous data collection, and the research team remained nimble, faced with constantly shifting contextual dynamics that are common in an unstable, rapidly developing urban slum. Consistent with the evidence base, as a result, the process was reflexive, flexible, and iterative (Reference Cornwall and JewkesCornwall & Jewkes, 1995). Ghana is an Anglophone country, so the process was conducted in English except where otherwise noted.

3.3 Piloting and Results of the Intervention Components

The research director suggested initial steps, with significant input by Sr. Matilda and the Department of Public Health. Reflecting PAR principles developed around priority setting, throughout the process the research team trained the stakeholders on the relevant collaboration evidence, supported their decision making, and collected data from the stakeholders to feed back into the process (Reference Patten, Mitton and DonaldsonPatten, Mitton, & Donaldson, 2006). Each phase resulted in decision making by consensus, meaning that all stakeholders came to agreement on the decision. Thus, when this Element describes how “the collaboration” took an action, that means research participants in a full FGD or smaller FGD reached a consensus-based decision, decided on a follow-up action, and designated one or more research participants to take that action on behalf of all participants in the collaboration. The results of each PAR phase are organized by the two main themes that emerged: process management of the cross-sector collaboration and strategy and project development based on the stakeholders’ priorities. There were three phases to the PAR process.

3.3.1 Phase I: Key Informant Interviews and Process Management Results

In February 2015, as described in Section 3.1, the research director conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews that lasted between one and four hours, with a purposive sample of eleven potential stakeholders: five non-governmental (four congregations of Catholic sisters and NCHS), six governmental (three AMA and three Ghana Health Service), and one community member. The scholarly literature suggested interview themes including experience with collaboration, strategic interests of each individual and their organizations, and prior relationships among the interviewees (Reference KritzKritz, 2017). The interview protocol was later adapted (Appendix A) for use in initial interviews with new stakeholders. Interviews were recorded through note-taking, along with detailed notes on emerging issues, ideas, activities, and informal conversations with key actors. This practice enhanced reflexivity, supported active listening in the interview process, and enabled triangulation with other data during the analysis stage. The research director constructed the interviews to educate the interviewees about cross-sector collaboration.

Through the interviews, the three initial stakeholders described earlier agreed to enroll as research participants. The research director triangulated the interview data with follow-up email and telephone conversations for clarification and used qualitative content analysis to identify themes, areas of consensus, important strategies to explore, cultural norms around the idea of working together, as well as terminology, common expressions, and key concepts related to cross-sector collaboration in Ghana. Two themes emerged: (1) due to the volatile nature of the slum environment, process management of the collaboration required significant attention and (2) projects were needed to address community needs, which included understanding community priorities along with prior strategies and efforts to address them.

All interviewees were unfamiliar with the term “cross-sector collaboration.” When it was described to them, 100 percent said they worked through cross-sector collaboration in the past. Each of the stakeholders understood cross-sector collaboration as a method through which they naturally operated in some cases. They all understood that it is a very challenging approach and appreciated that it is valued as highly effective when it succeeds. Agreed-upon local terminology, common expressions, and key concepts resulting from the interviews were used and refined throughout the process.

The research participants reached consensus on several process results. The first was a decision to focus on the Old Fadama slum because it presented perhaps the greatest challenge to Accra’s development. This decision shaped Collaboration Principle 1, identification of a complex challenge. The second result was the stakeholders’ willingness to participate in cross-sector collaboration to solve problems with this community. This decision, along with an agreement to resource their own participation, became Collaboration Principle 5. The third result was consensus on the importance of engaging Old Fadama community leaders to design and implement a strategy, coupled with agreement on the importance of not contacting them until the stakeholders were ready to take action so as to not “disappoint” the leaders. This decision shaped Collaboration Principle 4, to employ emergent design and governance.

In June 2015, heavy rains caused floodwaters to rise to the tops of Old Fadama buildings. Flooding throughout the city killed or injured more than three hundred people. Many Accra residents believed the slum caused the flooding. They blamed the residents specifically for infilling and silting the river and lagoon. As a result, the AMA demolished the area of Old Fadama that encroached upon the river and lagoon. They provided transport for displaced residents, even paying some of them to return to their homes in northern Ghana. The resettlement effort was ineffective: many residents jumped from the transport before even leaving Accra, while others used the transport as an opportunity for a free ride to visit home, returning to Accra later in the year. The bulldozing and resettlement caused considerable tension that erupted into violence. These developments also demonstrated that bridge building between the municipal government and the community was absolutely essential, leading to the idea of middle-out collaboration that became Collaboration Principle 3. This project’s three initial research participants considered changing locations due to the increased violence and anger. However, they decided to continue to work in Old Fadama because, after the flooding and the failed resettlement, the residents’ need was even greater.

3.3.2 Phase II: Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

As noted in Section 2.5.3, when cross-sector collaboration is not government mandated, the literature suggests starting with a small group of stakeholders and expanding as the momentum grows (Reference Bryson, Crosby and StoneBryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015). Citizen participation in government planning is known to be increasingly important (Reference FagenceFagence, 2014). However, there is a gap in research around participation in government planning in Africa (Reference Kapiriri, Ole Frithjof and KristianKapiriri, Ole Frithjof, & Kristian, 2003; Reference MalukaMaluka, 2011). The PAR process was designed to build government capacity to incorporate citizen participation, so that data from the grassroots could inform government planning.

The research director and initial stakeholders agreed that the next step should be a meeting to involve community leadership. As described earlier, due to the conflicted relationship between the municipal government and the community, it was clear that neither could facilitate the collaboration due to a lack of trust. It was at this point that Batsa was engaged as a facilitator to collect data on the PAR process and to work alongside the Catholic sisters and build bridges between these conflicted parties. In all, there were four FGDs, designed to engage the community leadership, identify community priorities, align these priorities with government planning, create strategies, and implement a project. The research director and the facilitator designed the FGDs and collected the data, audio recording the focus groups for later analysis. Participant observation was important, so interactions were captured through note-taking, including recording nonverbal expressions.

Batsa facilitated each FGD. He and the research director provided consultation on cross-sector collaboration theory and evidence to inform the research participants. During each FGD, the facilitator worked with existing research participants to identify new stakeholders, based on the criterion that they might play a long-term role in implementing the project strategy. Research participants achieved consensus on identifying additional participants to invite. Based on prior experiences with short-term interventions, the research participants’ criteria excluded international NGOs, which are generally funded for short project cycles that are unsuitable for complex challenges such as Old Fadama.

The research director and facilitator constructed the FGDs (Appendix B) to give all participants the opportunity to express their own thoughts about the collaboration process and projects. The research director used qualitative content analysis to understand participants’ shared opinions on process management, priorities, strategies, and projects. The research director triangulated the results from each FGD with the participants, facilitator, and initial stakeholders (Boateng, Imoro, and Sr. Matilda). Because the results captured decisions that were made by consensus, triangulating usually meant ensuring the language of the results matched the stakeholders’ intention and confirming their agreement (given a chance to think more about it) with the decisions they made. This cross-checking was conducted with the initial stakeholders and other participants in each FGD, until the research team believed consensus was achieved. In this way, the results were continuously updated based on developments in the community and among the stakeholders. The research team analyzed the data for each FGD separately and then together as a whole to understand differences in the FGD participants’ attitudes, beliefs, and opinions and how these changed over time. These results, too, were shared with the initial stakeholders and the participants in each FGD in an iterative way to continually update the research participants on the decision making.

FGD 1: Catholic Sisters (Eight Catholic Sisters, Purposive Sample)

The sisters’ FGD was conducted in Sr. Matilda’s offices with eight participants from three Catholic sisters’ congregations focused on community work. This FGD was interesting in that the participating congregations freely gave feedback on the Old Fadama collaboration, but other than Sr. Matilda’s congregation, they were not interested in joining as research participants. It was not clear why, at the time. However, the research director later learned from members of the Catholic Church hierarchy that there had been a history of serious collaboration failure and resulting conflict between sisters’ congregations in Accra. Neither the sisters participating in the FGD nor in fact any of the sisters currently working in Accra participated in the collaboration failure or were even aware of it. However, the failure was thought to have shaped their organizational norms. As a result, the church hierarchy perceived collaboration between sisters’ congregations in Accra as very challenging.