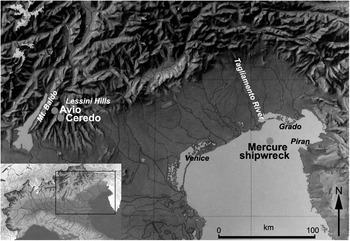

This paper describes and discusses a group of gunflints recovered during underwater excavations carried out in 2004–11 on the 16-gun brig Mercure (later renamed the Mercurio) found in the northern Adriatic. The vessel, built for the French navy in Genoa in 1806, entered the Napoleonic Italic Kingdom fleet, based in Venice, in 1809–10.Footnote 1 The ship was sunk on the morning of 22 February 1812 by the British brig Weasel (or Weazel) in the Grado (also known as the Pirano) battle while it was on a mission to escort the 80-gun vessel Rivoli out of the Venetian lagoon.Footnote 2 The Mercurio was commanded by Lieutenant Palinucchia (or Palincucchia) and the crew consisted of ninety-two men, including five officers.Footnote 3 The wreck was discovered accidentally in 2001 at the depth of 16–17m below sea-level, some 7 miles (11km) off the Punta Tagliamento, in the delta of the River Tagliamento, along the present coast of Friuli, south of the city of Lignano Sabbiadoro (fig 1).Footnote 4 At the time of its discovery the shipwreck was in a good state of preservation (fig 2), protruding from the sand on the seabed, with only a tumulus of concretions and some iron carronades around it. Although split in two main parts, lying some 70m apart (excavation Zones A and B respectively),Footnote 5 the Mercurio is so far one of the best-preserved underwater wrecks of this period in the Mediterranean Sea.

Fig 1 Location of the Mercurio shipwreck and of the flint sources and workshops discussed in the text. Drawing: E Starnini

Fig 2 The Mercurio: the left-hand side of the hull in the prow area. Photograph: S Caressa

As well as the remains of seven crewmen, ranging in age from sixteen to forty-five,Footnote 6 some 900 objects were brought to light during excavations carried out by Ca’ Foscari University, Venice.Footnote 7 These included a large number of firearms: one bronze swivel gun, eight 24-pounder iron carronades, two 8-pounder iron guns, five pistols (pistolet de bord) model 1786, made in Tulle,Footnote 8 one musket (mousqueton de hussard) model 1786, probably made in Brescia,Footnote 9 one musket butt plate, three plate locks of small arms, some iron cannon balls and hundreds of lead musket balls, as well as the gunflints that are the subject of this paper. The gunflints come from the bow (Zone A, squares 8 and 9), where the pistols, musket and human remains were found.Footnote 10 Although the gunflints could be used for artillery, none of the carronades of the An xiii model or the 1786 model guns found aboard the Mercurio were equipped with a gunlock.Footnote 11 However, the brass fragment (see fig 9, bottom) is clearly a piece of a gunlock produced in Paris, suggesting that there were cannons on board the Mercurio that were equipped with this technological innovation.

The study of gunflints from shipwrecks has slowly gained ground during the last fifteen years.Footnote 12 Nevertheless papers on this specific topic are still few, despite their importance for the recognition of gunflint production centres, their raw material provenance, the trajectories of military supply and trade routes, and their exploitation and use by crew members of different nationalities. Locating the raw material sources for the manufacture of gunflints, their production methods and typological analysis are all important steps in the study of the weaponry utilised on Italic Kingdom Napoleonic vessels, which depended also on the nationality of the crew members (we know that Dalmatian, Istrian, Venetian, Genoese and French sailors served on the Mercurio). Problems that could hamper such studies derive from their deposition, patination and state of preservation in Mediterranean seawaters,Footnote 13 as well as the occasional presence of concretions.Footnote 14

The study of gunflints has so far been concerned mainly with British,Footnote 15 French,Footnote 16 Danish,Footnote 17 Dutch,Footnote 18 East European,Footnote 19 South BalkanFootnote 20 and American assemblages,Footnote 21 although the provenance of the raw material sources employed for their manufacture is sometimes difficult to assess.Footnote 22 By contrast, insufficient attention has been paid to the Lessini Hills (Ceredo) and Monte Baldo (Avio) production centres,Footnote 23 the most important suppliers of the imperial army of the Habsburg monarchy.Footnote 24 Millions of pieces were produced and exported every year from the workshops located around Ceredo (Verona) and Avio (Trento) that were active mainly during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.Footnote 25

A manuscript written in 1820 by Dr Bourgoin reports: Dans le Veronais on traitait des silex de Montebaldo, lequel était grisâtre, d’une pâte assez fine e dure, ressemblant à l’agate; les pierres à fusil ne pouvaient fabriquer qu’au rouet et leur prix était trop élevé pour pouvoir être adoptées dans l’usage général (‘In the Verona region they also work flint from Montebaldo, which is greyish, of very fine and hard texture, similar to agate; the gunflints can be produced only by hammering, and their price is too high for them to be adopted for general use’). Some half a century earlier, General J-J Gassendi had observed that Veronese gunflints were more than twice as large as French specimens and their quality inferior.Footnote 26 According to J Emy, author of the seminal volume on gunflint production from Verona province,Footnote 27 they were roughly made, and their shape was irregular.Footnote 28

Mitchell was the first to describe British gunflint manufacturing,Footnote 29 followed some forty years later by Skertchly.Footnote 30 Salmon did the same in France before the end of the century.Footnote 31 Blade gunflints were produced in both countries using similar techniques.Footnote 32 Although good information was already available for gunflint manufacture from a few other European countries before the 1980s,Footnote 33 data on the topic were still very poor for the Lessini Hills gunflint workshops until the publication of the excavations carried out near Ceredo by J N Woodall et al.Footnote 34 These revealed the importance of the Ceredo production centre, as well as helping to define the different manufacturing stages and the characteristics of the final products; these are somewhat similar to those from Britain, but broader and thinner.Footnote 35

THE MERCURIO GUNFLINTS

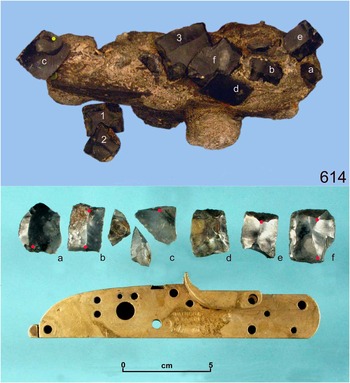

The Mercurio chipped stone assemblage discussed in this paper consists of eighty-five gunflints (figs 3 to 7; tables 1 and 2). They were all recovered from excavation Zone A, squares 8 and 9 (fig 8). Nine specimens were retrieved from a single concreted block together with a metal fragment of French cannon gunlock (fig 9).Footnote 36

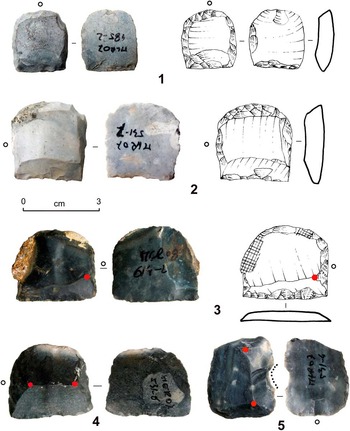

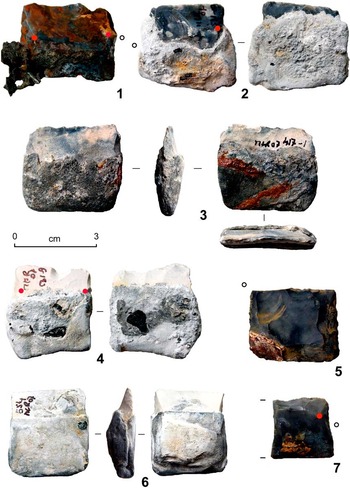

Fig 3 D-shaped gunflints of Class 1 (nos 1–4) and utilised gunflint of Class 3 (no. 5), with indication of the percussion bulb (black circles) and bevel arrises (red dots). Drawings: P Biagi and E Starnini; photographs: E Starnini

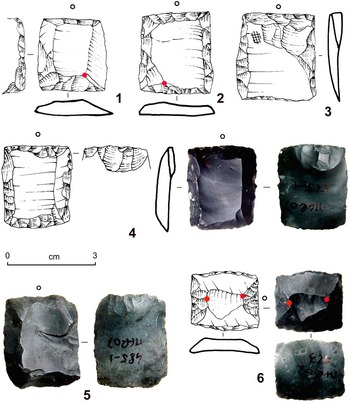

Fig 4 Gunflints of Class 2 (nos 1–5) and Class 3 (no. 6), with indication of the percussion bulb (black circles) and bevel arrises (red dots). Drawings: P Biagi and E Starnini; photographs: E Starnini

Fig 5 Gunflints of Class 2 (no. 1), Class 3 (nos 2, 4 and 5) and Class 4 (no. 3), with indication of the percussion bulb (black circles), bevel arrises (red dots) and ventral bulbar scar (yellow dot). Drawings: P Biagi and E Starnini; photographs: E Starnini

Fig 6 Gunflints of Class 4 (nos 1–7), with indication of the percussion bulb (black circles) and bevel arrises (red dots). Drawings: P Biagi and E Starnini; photographs: E Starnini

Fig 7 Gunflints of Class 4 (nos 1, 5 and 7) and Class 3 or 4, partly covered by a lead sheath (nos 2–4 and 6), with indication of the percussion bulb (black circles) and bevel arrises (red dots). Photographs: E Starnini

Fig 8 Distribution of the gunflints recovered from excavation Zone A, squares 8 and 9. Class 1: green dot; Class 2: red dot; Class 3: blue dot; Class 4: black dot; Class 3 or 4: black and red dots. Drawing: S Manfio

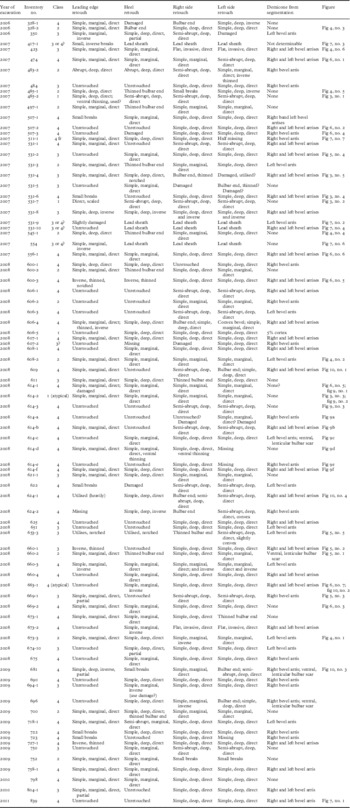

Table 1 Class attribution and retouch characteristics of the Mercurio gunflints

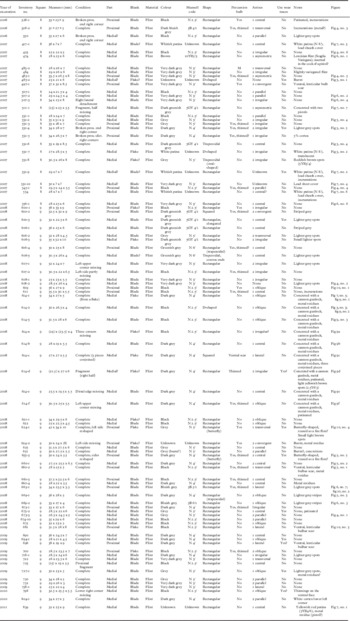

Table 2 Provenance, material, manufacture and raw material characteristics of the Mercurio gunflints

All the gunflints except one are obtained from black/dark-grey/bluish-grey flint, with small whitish spots or lighter grey variegations or stripes (see table 2). The precise flint source exploited for their manufacture is so far undefined. According to our present knowledge, only one Mercurio gunflint was knapped from the brown spotted Lessini flint,Footnote 37 characteristic of the ‘Biancone’ and ‘Scaglia Variegata’ flint formations of the Veronese Lessini Hills and Trentino,Footnote 38 whose geological location is well known.Footnote 39 The remainder are more like Monte Baldo gunflints in their use of a distinctive type of greyish flint,Footnote 40 the outcrops of which might be those that are described by Barbieri et al,Footnote 41 consisting of greyish spotted flint formations in the Scaglia Variegata deposits that supply nodules of ‘sufficient’ quality for knapping.Footnote 42 Furthermore, black and dark grey flint is available from the moraines of the River Tagliamento and from the Carnic Pre-Alps, in the Friuli region of north-eastern Italy.Footnote 43 These were exploited for making chipped stone tools as far back as the beginning of the Holocene.Footnote 44

In describing the morphology of the Mercurio gunflints (tables 1 and 2) we have followed the typology of Seymour Joly de LotbiniereFootnote 45 who subdivided them into four main classes: 1) D-shaped; 2) squared; 3) squared with two dorsal arrises; and 4) squared with only one arris.Footnote 46 The terminology adopted in this paper is that proposed by T B Ballin,Footnote 47 while the description of the retouching on the leading edge, heel and sides follows that introduced by G LaplaceFootnote 48 for prehistoric chipped stone tools. Four Mercurio pieces have been attributed to Class 1, thirteen to Class 2, seventeen to Class 3 and forty-six to Class 4. Four have been assigned to Class 3 or 4 because they were found still inserted in their lead sheath, and thus it has been impossible to observe their entire shape and study them in detail.

The typology, number of complete tools and high percentage of medial pieces retrieved from the Mercurio suggest that most specimens (85 to 92 per cent) were obtained from blades that were long, wide and thin. The presence of one or two small dorsal scars is typical of a knapping technique involving hard hammering when the blade was positioned on a stake (fig 10, nos 1 and 2).Footnote 49 The same can be said for the presence of three specimens with wide ventral lenticular bulbar scars (fig 5, no. 1; fig 10, no. 3) consequent on violent hard-hammering detachment with a metal-pointed tool.Footnote 50 Only seven to fourteen specimens are obtained from flakes (fig 7, no. 5). Just a few pieces show an invasive thinning retouch to remove the bulb at the proximal ventral end (fig 4, nos 4 and 5; fig 5, no. 5). Most of the gunflints look new and unused, except for a few specimens with traces of wear (see table 2) or a chipped leading edge (fig 3, nos 1 and 2; fig 5, no. 4). Only two have a notch at the centre of the leading edge (fig 3, no. 5; fig 10, no. 4). Two butterfly-shaped specimens with evident traces of use, in the form of notches along both sides, might have been reutilised as fire flints (fig 5, no. 5).

Fig 10 Proximal, right bevel arris of gunflint 609 (no. 1); proximal, left bevel arris of gunflint 663-1 (no. 2); ventral bulbar scar of gunflint 681 (no. 3); and utilisation traces of gunflint 624-1 (no. 4). Micro-photographs: E Starnini

All the gunflints have been measured by orientating the piece according to its original blank axis.Footnote 51 The dimensional analysis, exemplified by the length/width and length/thickness diagrams (fig 11), show that the Mercurio samples consist not only of different types, but also that their dimensions differ, spanning 23 to 41mm in length, 21 to 34mm in width and 4 to 10mm in thickness. Their average size differs from that of both French and British types.Footnote 52 A closer comparison is with rectangular specimens from Andalucia.Footnote 53 The variable size and shape suggest that they were employed in different types of firearm.Footnote 54 Fortunately, the lead sheath into which four military gunflints of Class 3 or 4 are inserted has been preserved (fig 7, nos 2–4 and 6).Footnote 55 Three of the leaded specimens are covered by a whitish patina that rarely occurs on other samples from the same assemblage (fig 7, nos 3, 4 and 6).

Fig 11 Length/width (left) and length/thickness (right) diagrams of the seventy-two complete gunflints. The colours indicate the four different classes (1 to 4) into which they have been subdivided. The vertical lines represent the maximum and minimum dimensions of the different classes throughout the assemblage. Drawing: P Biagi

Two of the Mercurio gunflints (fig 3, nos 3 and 4) are similar in material and shape to some pieces from Castle Neugebäude, on the outskirts of Vienna, where an impressive cache of gunflints, chronologically attributed to the siege of Vienna by Napoleon in 1805, has been recovered.Footnote 56 They have been attributed to the Lessini Hills manufacture area.

DISCUSSION

The gunflints excavated from the bow (excavation Zone A) of the Mercurio represent the only assemblage of this type ever studied from a shipwreck of the Napoleonic-era Italic Kingdom. The scope of the present analysis is to shed some light on a few important topics, among which are: 1) typology; 2) manufacture; 3) raw material provenance and circulation; and 4) the function of the specimens. Our conclusions for each of these points is briefly summarised below.

-

1) The tools have been described according to well-established typologies to enable comparison with other assemblages with similar characteristics in the future. Although not exactly identical, a few specimens recall D-shaped French types (fig 3, nos 1–4).Footnote 57 The typological and dimensional characteristics of all the other specimens show that they were undoubtedly produced from north Italian production centres, most probably located around Avio in Monte Baldo (Trentino), for use in military weaponry.

-

2) They have been manufactured according to a technique well known from Britain, France and the Lessini Hills (Verona),Footnote 58 in which the gunflints were produced from segments of blade that were long, wide and thin. While the British knappers (from Brandon, for exampleFootnote 59 ) were capable of obtaining four to five specimens from each blade,Footnote 60 the north Italian knappers produced only one (or two?) pieces per blade using the same knapping technique. The Italian products were made from a lower-quality flint, sometimes of irregular shape.Footnote 61 Although most of the Mercurio specimens were obtained from the central part of the blade, the bulb of the proximal pieces is always absent, or removed, or thinned by a ventral, flat, invasive retouch (see fig 4, nos 4 and 5). A few pieces show a characteristic lenticular bulbar scar on the ventral surface due to violent hard percussion with a metal hammer (see fig 5, no. 1), and one or two dorsal scars at the edge of the arrises. These latter are typical of the manufacturing technique of the British, French and north Italian knappers.

-

3) The precise location of the flint source is uncertain, though it is undoubtedly from somewhere in north-eastern Italy. Only one specimen is probably made from Lessinian, Scaglia Variegata brown flint (fig 6, no. 1).Footnote 62 All the other Mercurio gunflints have been obtained from grey and black flint, similar to that employed in the Lessini Hills and Avio workshops, whose provenance is most probably to be found within the Monte Baldo Scaglia Variegata formation or as naturally transported nodules in the Friuli Tagliamento moraines. The flint, although varying in colour and texture within the same geological formation, is easy to recognise because of its vitreous appearance and the presence of many small, lighter or white spots all over its surface. The Avio workshop is the most likely source of the Mercurio gunflints, a view supported by historical sources.Footnote 63 Gunflint workshops are reported to have been active around Avio until 1819, and the remains of gunflint workshops have been recognised at Pra di Stua.Footnote 64 Production here seems to have ceased because of the lower quality of flint supplied by the local outcrops.Footnote 65

-

4) The presence of different types of weapons and of crew members of several different nationalities on board the brig supports the idea that the Mercurio gunflints were used to arm a wide variety of firearms, probably produced from different countries, although the arms retrieved from excavation do not bear this out. The gunflint assemblage so far recovered during excavation is small compared to the quantity that was probably needed to supply such vessels during complex war operations, which probably carried several barrels of ammunition.Footnote 66 It is difficult to understand why north Italian gunflints made from lower-quality flint were used on a Napoleonic vessel moving across insecure waters, and fighting against a very difficult enemy whose weaponry was undoubtedly superior to that of the Mercurio.

CONCLUSION

The small chipped stone assemblage of Mercurio gunflints contributes to a better understanding of the weaponry used on an early nineteenth-century ship, a topic still undeveloped in present-day archaeology.Footnote 67 Furthermore it opens new perspectives on the north Italian, Veronese and Trentino gunflint industry whose products, though mostly intended to supply the Austrian imperial army, was undoubtedly utilised also on Napoleonic vessels of this period. The reason why north Italian gunflints were used on the Mercurio, instead of superior-quality, longer-lasting French ‘du Berry’ gunflints that might guarantee better results in case of a battle,Footnote 68 is difficult to explain. Further reading and knowledge of the historical sources on gunflint commerce and the provenance of the military supplies of the Italic Kingdom navy, and the political reasons behind them, is greatly needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs G Trnka and M Brandl (Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory, Vienna University) for supplying the data regarding Monte Baldo (Trentino) flint outcrops, Avio gunflint production areas and Vienna Schloss Neugebäude gunflint caches; Mr G Chelidonio (Verona University) for the information regarding the Lessini Hills (Verona) flint and gunflint workshops; and Dr B A Voytek (Berkeley University) for the use-wear analyses. Special thanks are due to Dr T B Ballin (Bradford University) for his critical review of the manuscript and useful suggestions, and two anonymous Antiquaries Journal reviewers for their additional comments.