Introduction

Current scholarship offers two strikingly different angles to look at the political repercussions of structural economic change. Some observers highlight the ever-growing share of highly educated citizens whose coveted skills guarantee aggregate prosperity and growth in modern knowledge economies. At the same time, an influential literature emphasizes that the gains of economic modernization are distributed in a highly unequal way, which produces a rising pool of dissatisfied voters. The two accounts suggest fundamentally distinct prospects for political stability in advanced capitalist democracies. While widespread upskilling in the knowledge economy promises growing prosperity and, thus, a symbiotic relationship between capitalism and democracy, the second perspective paints a much more fragile picture. It stands to reason that both narratives hold some truth: stability and contestation hinge on the relative importance of the constituencies which either perceive that they have what it takes to thrive in the knowledge economy or are worried about their future place in a dynamic and fast-changing society.

This paper studies the structural foundations of party system change in postindustrial democracies by investigating how perceptions of long-term social and economic opportunity relate to electoral preferences. How does the position of voters in a changing economy affect their support for the political status quo? In the early twenty-first century electoral context, mainstream parties – and incumbents in particular – represent continuity, while radical parties fundamentally contest the existing economic and political order. Mainstream opposition parties might call for policy adaptation within the confines of the existing system, but they do not question long-term structural trajectories in the way that radical parties do (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). By looking at support for mainstream incumbent parties, mainstream opposition parties, and radical parties, we focus on expressions of varying degrees of willingness to upend the political status quo.

Focusing on prospective evaluation of opportunities, we build on recent contributions on long-term party system change that have increasingly recognized the limited explanatory power of immediate material circumstances for individual political behaviour. A rapidly growing literature has started to look beyond objective socioeconomic status and introduced subjective, relational, and long-term understandings of societal position to identify ‘winners’ and, especially, ‘losers’ of structural change (Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon2019; Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Gest Reference Gest2016; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016; Kurer Reference Kurer2020; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew2017; Rooduijn and Burgoon Reference Rooduijn and Burgoon2018; Smith and Pettigrew Reference Smith and Pettigrew2015; Steenvoorden and Harteveld Reference Steenvoorden and Harteveld2018; Teney, Lacewell, and Wilde Reference Teney, Lacewell and Wilde2014). What these studies have in common is a conceptualization of voter perceptions that refers to their present or retrospective experience. We argue that many of the core conflicts arising from the emerging knowledge economy are of an equally relational and long-term oriented but inherently forward-looking nature: voters' belief in the political system is based on perceptions of prospective opportunities – for themselves as well as the next generation.

The expectation of a system-stabilizing effect of positive future opportunities is in line with core insights of the literature on economic voting, which concludes that voters' perceptions of economic conditions (versus their objective material conditions) and their short-term prospective (alongside retrospective) evaluation of the economy most consistently relate to support for incumbent government parties (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke2004; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Reference Lewis-Beck, Stegmaier, Dalton and Klingemann2007). However, the fundamental, long-term nature of ongoing transformations of the economy and electoral realignments implies that beyond the familiar distinction between incumbent versus opposition parties, we should further distinguish between more versus less radical forms of opposition (Hernández and Kriesi Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). Moreover, the above-cited literature on changing social hierarchies in times of structural change indicates that voters' sense of (lacking) opportunity relates to deeper grievances linked to questions of dignity, identity and belonging in a changing society. Such sentiments, in particular, provide a link to support for the radical right, which has posed the primary challenge to mainstream parties in recent decades. Consequently, our study integrates insights from the economic voting literature on government support with the findings of a growing literature highlighting the implications of a more structural backlash against economic change and the political elite.

More specifically, we argue and demonstrate that perceptions of economic opportunity cross-cut objective socioeconomic indicators, resulting in political coalitions that transcend vertical divisions of society. We discuss the relevance of two key constituencies emerging from our conceptual framework: aspirational and apprehensive voters. Aspirational voters are not immediate beneficiaries in the ongoing economic-structural context, but they are confident enough about their (and their children's) prospects to support a reformist, system-sustaining approach to policies and governance. They may play an important – perhaps even decisive – role in stabilizing democratic capitalism across advanced societies (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019).

However, we argue that there is also a highly relevant flipside to this line of reasoning: Apprehensive voters are relatively well-off in immediate material terms but are concerned about seeing society develop in a direction that threatens their and their children's sources of status and well-being. Consequently, they are wary of long-term structural change and its societal implications, perceiving ‘the system’ to steer in the wrong direction. Given that these voters perceive mainstream parties as complicit in the general thrust of economic and social change, we expect them to be generally more likely to support a radical contestation of mainstream parties' politics and policies. Specifically, a more diffuse sense of social dislocation should make these voters particularly receptive to the appeals of the radical right. In sum, we go beyond Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2019) by arguing that evaluations of prospective opportunities matter at lower and higher levels of material well-being.

Drawing on original survey data fielded in eight Western European countries, we provide evidence that positive perceptions of long-term economic opportunity – intra- as well as intergenerational – are consistently related to lower support for radical parties (but not to mainstream opposition, as expected). Notably, ‘aspirational’ voters support radical (especially radical right) parties at below-average levels, in stark contrast to well-off but ‘apprehensive’ voters. Only voters who are both doing well and are confident about the future support incumbents at above-average levels. We discuss the political implications of these findings by pointing to the cross-national distribution of these groups: while a coalition of confident and aspirational voters makes up for 60–70 per cent of the electorate in the Nordic and Continental European countries, more than 55–60 per cent of voters in Spain and Italy evaluate economic and social long-term prospects negatively.

Since this study is based on observational data, we cannot exclude that radical parties themselves generate and sustain negative views of the future among their supporters. However, while especially radical-right parties certainly mobilize such sentiment, our data indicate that the share of pessimistic voters does not relate to the size and strength of radical parties across countries. Rather, the shares of voters with optimistic versus pessimistic perceptions of future prospects seem to reflect structural context conditions: majority coalitions of optimistic voters emerge where welfare states are generous and accessible and where national knowledge economies provide labour market opportunities to match expanding skill supply.

Opportunity Perceptions and Electoral Choice

Empirical research on party system change in advanced democracies increasingly agrees that focusing on voters' objective and immediate socioeconomic status (for example, current income or employment status) is insufficient for explaining radical versus mainstream voting. Against many of the early hypotheses in this literature, according to which the unemployed, the poor and nonstandard ‘cheap labour’ was the recruiting ground for radical challenger parties (for example, Betz Reference Betz1993; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1999; King and Rueda Reference King and Rueda2008; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Mughan, Bean, and McAllister Reference Mughan, Bean and McAllister2003), we now know that the economic situation of voters needs to be theorized in their temporal and cross-sectional context. Accordingly, a burgeoning literature has adopted a more contextualized perspective on how socioeconomic circumstances might shape electoral choices.

To situate our perspective, we outline three ways in which researchers have so far adapted conceptualizations of socioeconomic status as a driving factor of political behaviour by (1) highlighting the importance of status relative to others, (2) emphasizing dynamic changes in status over time, or (3) focusing on the subjective nature of status perceptions.

First, research on relative deprivation emphasizes that voters compare their economic situation to others in society (Runciman Reference Runciman1966). If such comparisons lead voters to conclude that they are – unjustly in their view – dis-advantaged, this may fuel resentment and receptiveness for political appeals that play on that sentiment (Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon2019; Kurer Reference Kurer2020; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew2017). The importance of relative judgments of economic well-being is also evident in ethnographic studies, for instance, of members of rural or declining industrial communities who emphasize the struggles of their own working life while drawing comparisons to the (‘unfairly’) comfortable lives of professionals or public employees in thriving city centres (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Gest Reference Gest2016; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016).

Second, some researchers have looked at how dynamic changes in voters' (objective or subjective) socioeconomic status might explain political preferences. Burgoon et al. (Reference Burgoon2019) study ‘positional deprivation’, defined as a situation where the increase in disposable income of an individual is smaller relative to the growth in income of other groups in the same country's income distribution. Kurer (Reference Kurer2020) explores the employment trajectories of threatened routine workers, distinguishing relative and absolute changes in status. Gest, Reny, and Mayer (Reference Gest, Reny and Mayer2017) explicitly ask survey respondents to compare the status of ‘people like them’ today to what they think it was 30 years ago, while a dynamic perspective is also implicit in other studies on subjective social status and nostalgia (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Steenvoorden and Harteveld Reference Steenvoorden and Harteveld2018). Again, ethnographic work has captured perceptions of relative status loss using qualitative methods. Hochschild's (Reference Hochschild2016) metaphor of a social escalator on which members of the ‘old’ middle classes feel that they are overtaken by members of ethnic minorities, immigrants, women, or public sector workers vividly illustrates how changes in relative social status might matter to individuals (for Germany, see also Nachtwey Reference Nachtwey2016).

A third related strand of work has more generally emphasized the importance of subjective measures of immediate, relative, or dynamic deprivation (Teney, Lacewell, and Wilde Reference Teney, Lacewell and Wilde2014); or of subjective social status (Engler and Weisstanner Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021; Mutz Reference Mutz2018). Notably, Gidron and Hall (Reference Gidron and Hall2017) show that lower levels of subjective social status are associated with support for the radical right. They trace how the self-perceived status of men without a college education (relative to women) has declined in the past decades due to structural social transformations. Even if the relevant temporal reference points are not always discussed upfront, these concepts inherently include a relational element. Subjective judgments of status are also ever-present in the aforementioned ethnographic studies, focusing on individuals’ interpretations of their economic circumstances.

We learn from these contributions that to understand better how voters' economic situation affects their political behaviour, we need to capture how voters perceive their situation in context. And while this insight represents important progress, many status threats voters invoke when assessing their economic situation refer to the future – for example, work conditions deteriorating, risks of automation, prospects of ‘increasing’ immigration etc. Similarly, radical parties tend to operate with prospective narratives and scenarios of threat.

Consequently, we explore how voters' expectations for their future relate to their electoral preferences. This prospective focus shares similarity with the economic voting literature, which emphasizes the relevance of subjective evaluations of economic circumstances for incumbent party support (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke2004; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Reference Lewis-Beck, Stegmaier, Dalton and Klingemann2007). Our approach is complementary in that it adds a more long-term structural perspective on evaluations of the economy. We distinguish between mainstream incumbent, mainstream opposition and radical parties because the contestation of established mainstream parties by radical challengers is at the core of a fundamental realignment of European party systems that cannot be conceptualized in terms of incumbent versus opposition (Hernández and Kriesi Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016).

In theorizing the electoral implications of perceived prospects, we directly build on the argument that ‘aspirational voters’ play a vital role in stabilizing advanced capitalist democracies (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019). According to Iversen and Soskice, aspirational voters are voters who are not (yet) direct beneficiaries of democratic capitalism but who believe that they or their children have good prospects of someday joining the ranks of skilled workers employed in knowledge-intensive sectors. Aspirational voters believe they will benefit from structural change in the longer run. In the authors' account, this segment of voters stands for political continuity and ‘reformism’, thereby enabling the growth that eventually fuels demand for skilled and educated labour.

Conversely, Iversen and Soskice argue that anti-system appeals fall on fertile ground among those who feel excluded from the metaphorical escalator of progress. In this vein, the authors also point to the rapid spread of populism in the aftermath of the Great Recession. This observation resonates well with the findings of Hernández and Kriesi (Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016): With the economic crisis undermining confidence in incumbent parties, support for opposition forces is particularly likely to take the form of radical party support when voters cease to see a place for themselves and their children in an ever more knowledge-intensive, globalized society. Shorter-term, economic voting dynamics can hence accelerate the rise of radical parties.

We build on the conceptual contribution of Iversen and Soskice but differentiate more explicitly between subjective prospects and current socioeconomic status. While a positive evaluation of future opportunities may function as a buffer against supporting radical parties even among lower-status voters, a negative view of future opportunities may also drive well-off voters towards the fringes of the political spectrum. There is no reason to think that economically secure individuals should be immune from losing confidence in the capacity of the political-economic order to provide prosperity for themselves and their children. Differentiating prospects and status develops our theoretical expectations beyond a median voter argument towards conceptualizing different groups, their preferences and – importantly – their relative weight in society. It also extends a classical economic voting perspective by identifying two groups (mainstream opposition voters and radical opposition voters) who might be equally prone to punish incumbent parties for short-term economic downturns but who differ in whether their rejection of the incumbent extends to a more fundamental contestation of the political-economic system as a whole.

Theoretical expectations

Lacking confidence in the system's capacity to provide opportunities likely results in opposition against parties representing this system. However, beyond this hypothesized general anti-system effect, we are interested in whether and how the impact of voters' opportunity perceptions on party preferences varies with their immediate economic circumstances. Can confidence in future prospects compensate for a less-than-ideal present? Even lower-status voters in today's knowledge-based economy might support the current economic framework based on a positive evaluation of social mobility prospects – for themselves or the next generation. At the same time, even someone with a relatively high economic status today need not necessarily believe in a bright future. This reasoning (which extends to Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019) results in a two-by-two table in which we distinguish voters with positive and negative expectations regarding their opportunities on the one hand and high versus low current income on the other (we will consider finer breakdowns later on in the empirics). Table 1 summarizes our main expectations regarding distinctive electoral preference hierarchies for each quadrant.Footnote 1 Our expectations are fairly straightforward regarding the two unconflicted quadrants where economic circumstances and expectations about opportunities reinforce each other. First, high-income voters with a positive evaluation of future opportunities are beneficiaries of today's political-economic set-up, and they do not expect this to change. On average, these voters (whom we label ‘comfortable voters’) have every reason to support mainstream parties, particularly incumbent parties, because these have built and defended a system that delivers for them.

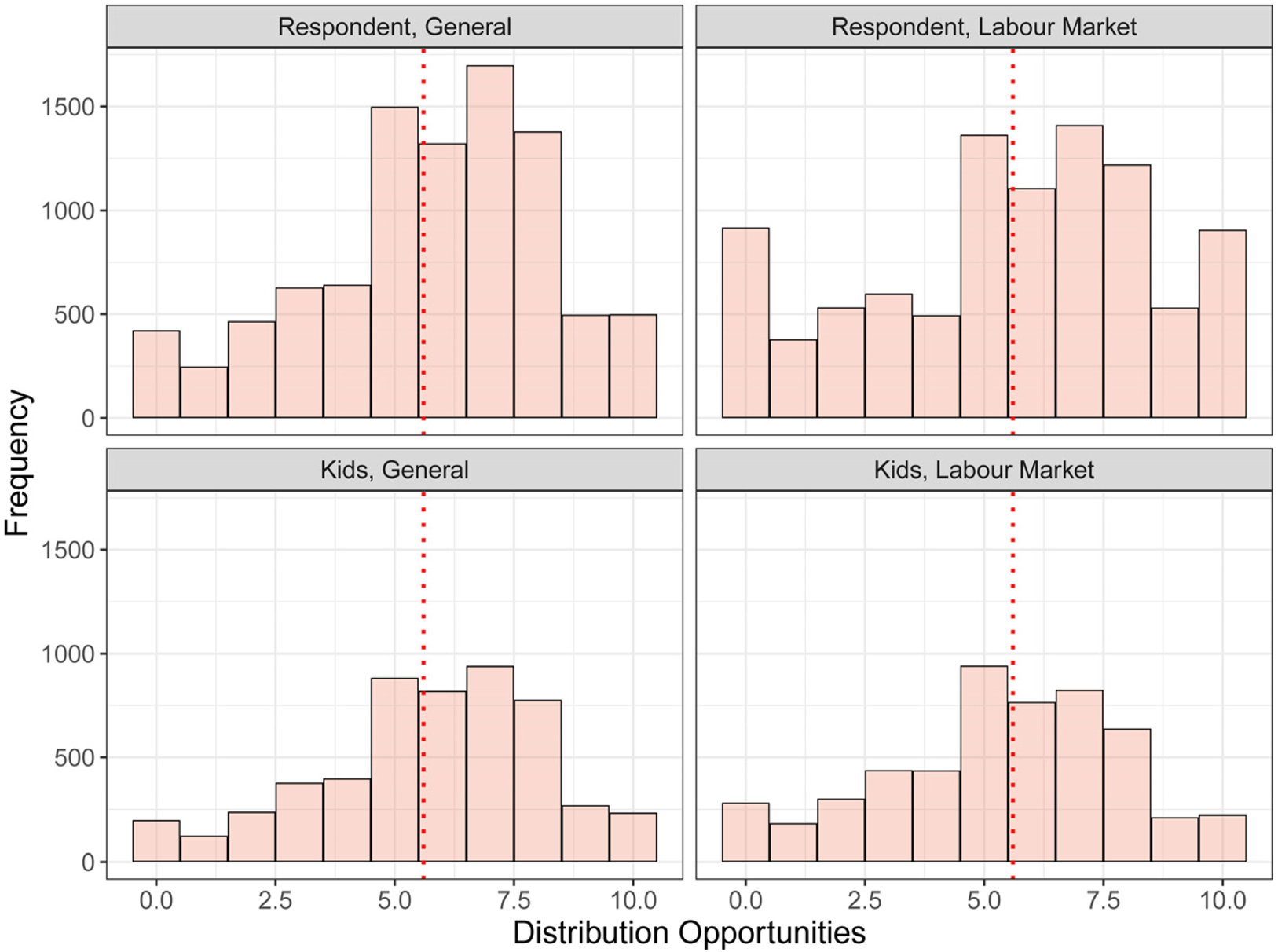

Figure 1. Distributions by opportunity type (vertical dotted line indicates mean value).

Diametrically opposed are low-income voters with negative evaluations of their future opportunities, whom we expect to be prone to opposition support (or to abstention). Even more so than mainstream opposition voices, we expect the appeals of radical parties to resonate particularly with this group. Voters in this quadrant (whom we call ‘burdened voters’) are not faring well in the modern knowledge economy and they perceive their long-term perspectives to be as bleak. Hence, we expect them to support radical parties over-proportionally, followed by mainstream opposition parties.

The remaining two quadrants are interesting because of how perceptions of opportunities might counterbalance immediate economic conditions. This makes them potentially pivotal for coalitional electoral dynamics sustaining advanced capitalist democracies. For these two quadrants, we have no strong expectations about incumbent versus mainstream opposition support per se. In our view, cross-pressures stemming from current status as opposed to future opportunity perceptions, ideological considerations, or short-term economic voting might turn these groups in favour of either incumbent or mainstream opposition parties. However, these two conflicted groups' diverging confidence in opportunities delivered by the knowledge society results in clear expectations about their propensity to support radical parties over-proportionally.

Lower-income voters who are nevertheless optimistic about opportunities correspond to Iversen and Soskice's aspirational voters: they have not (yet) fared particularly well, but they are confident that the existing political framework generates opportunities for them and their children. Such voters' bet on the knowledge economy should be associated with general support for parties that defend this order, that is, both mainstream incumbent and opposition parties while working as a buffer against radical parties. Radical disruption to the ‘rules of the game’ may obstruct already internalized visions for upward mobility.

Lastly, we are left with higher-income voters who evaluate future prospects negatively (our ‘apprehensive voters’): these are ‘winners’ of the prevailing political-economic order, but they nevertheless worry about what the future might hold for them or their children. These worries may be rationally founded (think of skilled but relatively lower-educated routine workers in declining industries) or more culturally based on perceived threats to lifestyles and norms (for example, with regard to a male breadwinner role model, belonging to the ethnic majority group, etc.) We expect the perceived threat of economic and status decline to predispose these voters towards radical parties rather than established mainstream parties (whether in government or opposition).

In terms of the mechanisms translating ‘apprehensive voters' negative evaluations of the future into support for radical parties, we can build on the rich and growing literature on how subjective and relational concepts of well-being contribute to explaining voting behaviour. Precisely because we define apprehensive voters as being well-off in terms of immediate material conditions (notably having relatively higher income), we would expect their concerns to take a more diffuse form, spreading to (and easily directed at) the more encompassing ways in which the economy and society are changing. Rather than worrying about immediate risks that might be mitigated within the existing system of advanced democratic capitalism – for example, with social insurance and transfers (cf. Gingrich Reference Gingrich2019) – these voters experience a more fundamental sense of dislocation as occupational status hierarchies, family models, gender roles, and other aspects of social life transform. This should translate into a more profound and encompassing sense of discontent with the direction in which established political forces are taking society. We expect such disaffected but well-off voters to see mainstream parties (incumbents and opposition, left and right) as broadly complicit in the transformation towards a knowledge-based modern society, pushing them towards the radical (and often anti-eliteFootnote 2) fringes of the party spectrum in general.

Data and operationalization

We rely on original survey data collected in eight West European countries (1,500 respondents each): Denmark, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, the UK, Italy, and Spain (http://welfarepriorities.eu/). This country selection not only maximizes variation in terms of welfare regimes and electoral institutions but, importantly, also encompasses countries with strongly differing structural and cyclical economic performance. In particular, Spain, Italy, and Ireland were on a strong upward macroeconomic trajectory in the years leading up to the survey while facing deep-rooted structural economic challenges, especially in terms of labour market performance. At the same time, Sweden, Denmark and Germany exhibit stronger structural performance but overall stability in the immediate period leading up to the survey year. This variance delivers suggestive evidence to demarcate our perspective from short-term retrospective economic performance as a determinant. The target population was a country's adult population (>18 years), with quotas on age and sex (crossed) and educational attainment. The total sample counts 12,506 completed interviews that were conducted between October and December 2018.

Independent Variables: Perceptions of Opportunities

We asked respondents about perceptions of economic opportunity concerning their own future and their children's (if any). The survey questions asked about both labour market opportunities (‘If you think of your future, how do you rate your personal chances of being in good, stable employment until you will retire?’) and general social opportunities (‘Now think beyond the labor market to your overall quality of life. How do you rate your personal chances of having a safe, fulfilled life over your life course?’) The questions were repeated to query respondents about their assessment of their children's chances on labor markets and life more generally. The precise wording and a correlation matrix of the various opportunity items is provided in Appendix B. Figure 1 shows the distributions of the four opportunity measures. The general skew to the left with mean values above the mid-point suggests that most respondents have rather positive evaluations of economic opportunity for themselves and their children.

Our procedure to test the theoretical expectations summarized in Table 1 is twofold. First, we create a categorical variable that emulates the four groups of voters at the centre of interest (aspirational, apprehensive, burdened and comfortable voters). To do so, we combine a dichotomized measure of perceived opportunities (positive versus negative) and a dichotomous measure of income level (above versus below the country-specific median income). In our main analysis, we rely on social opportunities for respondents themselves as the main indicator of positive/negative prospective evaluations. In additional analyses, we also define these groups on the basis of respondents' perceived labour market opportunities and on the basis of perceived opportunities for respondents' children to probe the robustness of our results and to discuss implications of the varying strength of the relationship depending on the precise operationalization of opportunity perceptions.

Table 1. Theoretical expectations: distinctive electoral preference hierarchies by quadrant

Second, we use the full, continuous information on respondents' income and opportunity perceptions and run regression models that include the interaction of these two variables. Note that, regardless of the level of current socioeconomic status, our framework suggests that positive evaluations of future opportunities should relate to higher mainstream party support (incumbents or opposition). We consider a possible interactive effect in the sense that high socioeconomic status and positive evaluations of future prospects may reinforce each other in how they relate to support for incumbents and mainstream parties more generally. However, our most important expectation is that negative opportunity perceptions relate to radical opposition support at high as well as low levels of socioeconomic status (that is, ‘apprehensive voters’ constitute an important group alongside ‘aspirational voters’).

Socio-demographic control variables

In order to assess how evaluations of opportunities affect electoral preferences at different levels of economic conditions, we must control for the socio-demographic profile of aspirational, apprehensive, burdened and comfortable voters. While we cannot establish the importance of opportunity perceptions without controlling for the composition of these groups, these socio-demographic profiles themselves are of interest. In advancing their original ‘aspirational voter’ argument, Iversen and Soskice (Reference Iversen and Soskice2019) hardly characterize aspirational voters other than saying they want to join the ranks of skilled workers. However, for the stability of advanced democratic capitalism, the question of who occupies our four quadrants is critical.

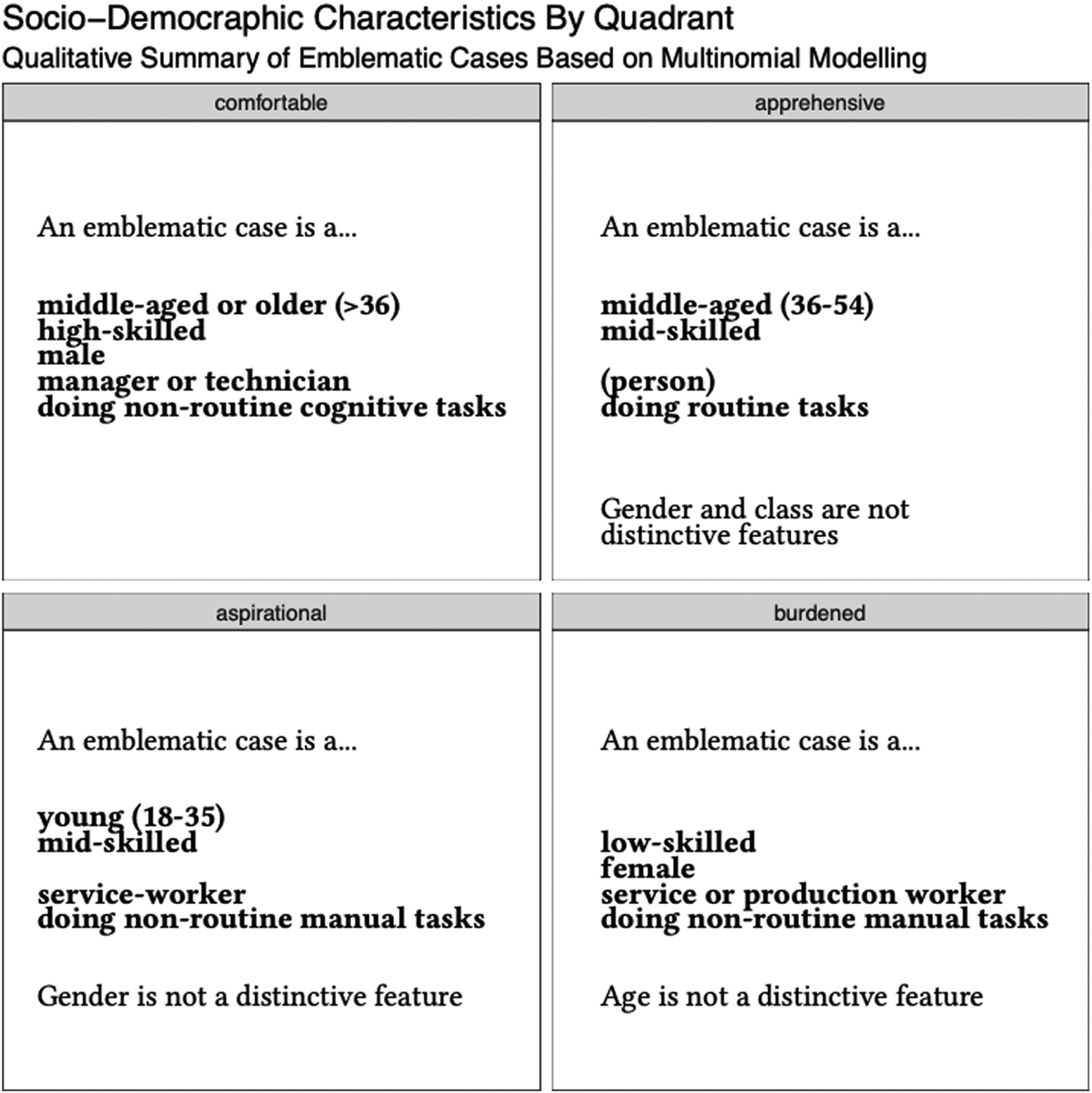

Figure 2 provides a general sense of each group's defining socio-demographic characteristics. The presented attributes give a qualitative summary of the characteristics of a ‘typical’ representative of the respective quadrant. The presented typical attributes are the result of a large number of descriptive quantitative analyses in which we ‘predict’ belonging to one of the four groups based on a range of important socio-demographics (see Appendix F for details).

Figure 2. Socio-demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of voter groups.

Although our four voter groups are, of course, heterogeneous in all of these respects, specific socio-demographic groups are clearly over-represented in each quadrant. For example, the over-represented among comfortable voters include managers, technicians, and sociocultural specialists. More generally, these are people with non-routine cognitive work. Meanwhile, service and production workers – in other words, people with non-routine manual or routine task profiles – are typical burdened voters. Comfortable voters are also disproportionately male and older (>55), while burdened voters tend to be younger and female. These two quadrants encompass a contrast between direct beneficiaries of the knowledge economy and those groups most clearly excluded from knowledge-intensive sectors of the economy, providing a first validation of how we operationalize our two-by-two table.

Age emerges as a key difference between aspirational and apprehensive voters. Aspirational voters are typically relatively young (18–35), while apprehensive voters are typically middle-aged (36–55). Service workers (and small business owners, but not production workers) or people in non-routine manual work are also well-represented in the aspirational group, as are people with medium levels of education. On the other hand, routine work is typical for apprehensive voters. The contrast between aspirational young service employees and apprehensive middle-aged routine employees bolsters our confidence in the operationalization of these quadrants.

Dependent variable: party preference

Following our theoretical framework, we group our dependent variable into three broad categories of political parties: mainstream incumbent parties, mainstream opposition parties and radical parties (see Appendix Table A.1 for the full classification).

Here, ‘radical’ does not exclusively mean ideologically extreme (in the sense of being radically to the right or left of the political spectrum). Under this label, we also classify parties that profoundly contest the existing political system. Rather than aiming for gradual change within the confines of democratic competition, radical parties demand more fundamental system change. Of course, this type includes the various radical populist parties from both the left and the right; but it also includes a party like the Italian Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S), which promises to go after the ‘caste’ of mainstream politicians based on an ideological position that seems to escape the traditional left-right dimension. With its strong anti-establishment and anti-corruption discourse, the M5S is in many respects comparable to its twin movements at both ends of the ideological spectrum in other advanced democracies (Font, Graziano, and Tsakatika Reference Font, Graziano and Tsakatika2021; Ignazi Reference Ignazi2021; Mosca and Tronconi Reference Mosca and Tronconi2019). In keeping with this theoretical distinction, we file contemporary green parties (present in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden) under mainstream parties. While ecological movements entered the political scene as radical parties challenging the status quo, we count them among the mainstream (left) here because they take a reformist stance on economic policies and democratic governance in the knowledge economy.Footnote 3 In line with the view that long-term economic and social change evaluations are associated with more fundamental endorsement versus rejection of the status quo, party type dominates incumbency status in our classification. This means that in the (rare) constellation where radicalism and incumbency come together, we continue to treat those cases as radical. When our survey was in the field (fall 2018), this primarily applied to the M5S and the Northern League in Italy (coalition partners in the Conte I government). At that time, these parties epitomized non-mainstream politics: Scholars have noted that the M5S-Lega coalition was seen as a ‘government of change’ that created ‘enthusiastic expectations concerning its capacity to overhaul politics’ (Giannetti, Pinto, and Plescia Reference Giannetti, Pinto and Plescia2020). Due to this demand for a complete political overhaul, we classify support for M5S and Lega as radical voting even though they had incumbency status simultaneously. In addition, we also classify the Danish People's Party as radical (rather than incumbent) even though they provided parliamentary support to the minority government in charge between 2015 and 2019. Following a similar logic, we expect that their passive participation in the government does not sufficiently dilute their radical(-right) profile in the views of supporters.

The presented results are based on respondents' vote choices in past elections, but they are robust to studying respondents' vote intention if there were elections next Sunday instead. The main difference is higher baseline levels of radical opposition support in vote intentions compared to past vote choices. In that sense, showing results based on actual vote choices in previous elections is a conservative modelling strategy. Aggrieved voters – or voters with a pessimistic outlook about their own and their children's opportunities – are quick to mention an intention to protest their grievances at the ballot box if they had the chance. However, supporting those radical parties on election day is a tougher test of our argument. Due to the categorical nature of the dependent variable, the main analysis relies on multinomial logistic regression models. We can recover all our results when using a set of separate logistic or linear probability models, in which the vote choice for each party is coded as either voting for a party or not. Note that the main difference of our set-up compared to traditional economic voting models is differentiation within the zero categories: rather than studying whether or not a respondent supports the incumbent party, we are also interested in different types of incumbent defection (mainstream versus radical opposition parties).

Results

We start by presenting the direct relationship between prospective economic opportunities and individual vote choice. We then take a closer look at the voting behaviour of our four groups of voters and at interactions between continuous measures of income and opportunity perceptions. This sets the stage for a subsequent investigation of the political implications of our findings, for which we will first break down our outcome variable into parties on the left and right and then discuss the relative importance of the four voter groups across countries.

‘Aspirational’ Versus ‘Apprehensive’ Voting

The direct effect of opportunity perceptions on voting provides initial evidence that prospective evaluations matter for radical versus mainstream voting, also allowing us to demonstrate the importance of looking beyond support for incumbent versus opposition parties when concerned with the political effects of voters' perceptions of the future. Table 2 (visualized in Panel (a) in Fig. 3) provides initial evidence that votes choice in favour of mainstream incumbent and opposition parties as opposed to radical parties is structured along a dimension of perceptions about future economic and social opportunity. Among respondents with more pessimistic views of future prospects, support for mainstream opposition parties is only marginally significantly higher than for incumbents (the reference category in the underlying multinomial model). However, these voters are significantly more likely to vote for radical parties.

Figure 3. General social opportunity and party choice (Multinomial).

Table 2. Opportunity respondent and party support (Multinomial, Reference: Incumbent Voting)

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. Multinomial Specification. All models include country-fixed effects.

Within country and net of income, age, gender, education, and occupational class, positive evaluations of opportunity are hence clearly associated with higher support for parties who broadly buy into the existing political-economic system (whether or not they are currently in government). Panel (b) in Fig. 3 demonstrates that these patterns are similar irrespective of whether voters were asked about their own or their children's general social prospects.

Figure 4 illustrates the importance of extending the economic voting literature's traditional measure of rejection/endorsement of the incumbent with the radical versus mainstream opposition distinction that is of key interest to the literature on structural transformations of party systems in advanced democracies. Negative prospective opportunities appear to be associated with a quite fundamental rejection of the political mainstream as a whole, not just with rejection of incumbents. As is evident from Fig. 4, failing to disentangle mainstream versus radical opposition to mainstream incumbents yields a moderately negative effect of perceived opportunities on support for the opposition as a whole. However, this moderate effect is an average of a strong negative association with radical party voting and a weak negative relation with mainstream opposition support. These findings thus provide initial support for the idea that positive evaluations of future opportunities among ‘aspirational voters’ may stabilize the political system by boosting mainstream party support in general.

Figure 4. Comparison to traditional economic voting: opportunity and party choice.

These findings hold when controlling for objective economic experience, which corroborates our interpretation that perceptions of long-term economic opportunity are more than just a correlate of past and current economic conditions. While we lack a survey item that directly asks how respondents see the current economic context, we present additional models that capture whether respondents (a) are currently affected by labour market vulnerability (unemployment or underemployment), (b) have ever received unemployment benefits or (c) believe in fiscal constraint by agreeing that ‘governments should not impose any further tax burden on citizens’. In the Appendix, we demonstrate that our results are entirely robust to the inclusion of these variables, either separately or jointly (Fig. D.1 and Table D.1).

Next, we further unpack the relationship between opportunity perceptions and electoral preferences by examining positive/negative expectations for voters at different income levels. We are interested in the extent to which the electoral implications of prospective economic opportunity depend on current material circumstances. Do negative evaluations of future opportunities only increase support for radical parties among less well-off voters, or do their appeals also resonate with higher-status voters? Beyond support for the mainstream opposition, can negative perceptions of long-term life prospects turn such higher-status voters against the political mainstream overall?

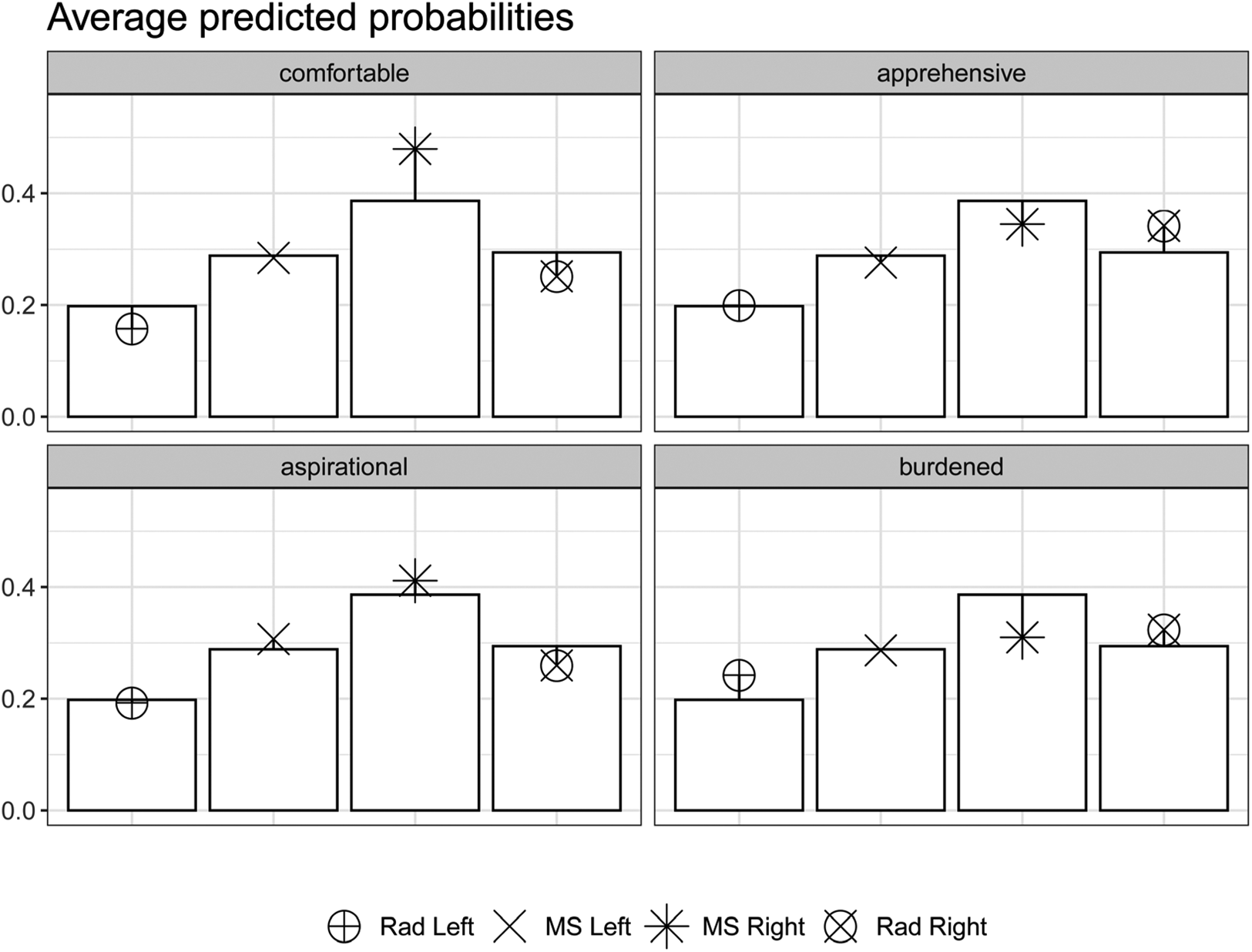

To that aim, we look at voting behaviour among the four types of voters introduced in the theory section by looking at predicted probabilities of party support by quadrant, controlling for age, gender, education, class, and country. Figure 5 shows predicted probabilities of support for mainstream incumbents, mainstream opposition, and radical parties. Table 3 shows full regression results. Here, we show our findings based on a set of separate logistic models to avoid a presentation of results relative to a reference category. Appendix Table C.3 shows the same results based on a multinomial regression. The figure displays unweighted average probabilities across all possible combinations of gender, class, education group, age group and country of residence. The white bars in the figure represent the average predicted vote shares for each of the three outcomes across the entire sample, offering a rough baseline probability of support. The shapes indicate quadrant-specific deviations from these baseline probabilities (corresponding to the ‘distinctive’ electoral preferences listed in Table 1).

Figure 5. Average predicted probabilities of support for different party types.

Note: Probabilities are unweighted averages across all possible combinations of gender, class, education group, age group and country of residence. The baseline (white bars) are average predicted vote shares by party family across the entire sample.

Table 3. Opportunity types and party support

***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. All models include country-fixed effects.

These predicted probabilities confirm that negative evaluations of opportunity increase radical party support. Support for radical parties is always higher on the right-hand side (negative evaluations) than on the left-hand side (positive evaluations). The reverse is true for mainstream parties, especially for incumbents.

As hypothesized, comfortable voters display above-average support for incumbents, below-average support for radical parties, and more average support for the mainstream opposition. For burdened voters, this is reversed. Next, among our cross-pressured voters (aspirational and apprehensive), the radical versus mainstream distinction appears to be more relevant than that between incumbents and mainstream opposition. Apprehensive voters support radical parties at above-average rates (but not the mainstream opposition), while the opposite is true for aspirational voters. Also viewed in absolute terms, aspirational voters – like apprehensive voters – have a similarly high probability of supporting mainstream incumbent and opposition parties.Footnote 4 This brings us to an important observation, namely that only the combination of high income and confidence in future opportunities appears to be associated with above-average levels of support for incumbent parties. This double-endorsement of the status quo is only truly characteristic of comfortable voters (and to a much smaller degree of aspirational voters). Voters who are well-off but ‘apprehensive’ about their future support incumbents at below-average rates (less clearly so than burdened voters, but in contrast to aspirational voters). Another important observation follows from this but draws attention to radical parties. While high socioeconomic status tends to reduce support for radical parties for both worried and confident voters, it only compensates for negative evaluations of future opportunities to a limited extent.

In sum, these findings support the idea that aspirational voters may join the existing ‘winners’ of the knowledge society. However, they also highlight that asking whether the median voter is aspirational is not enough. Well-off voters, too, might punish the established political elite as a whole when disenchanted with their prospects. This is a crucial addition to the original aspirational voter argument. Negative views of future opportunities among higher-income voters are associated with a pattern of voting behaviour that resembles that of outright ‘losers’ of the knowledge society more than that of comfortable voters.

Interacting Income and Opportunity

Interaction models, including the full range of both explanatory variables, are an evident alternative to creating discrete groups from dichotomized levels of income and opportunity (see Appendix Table C.4 for full regression results). Remember that our theoretical argument is consistent with but does not require that income and opportunity perceptions reinforce each other's effects. The four stylized groups of voters could also result from an additive process, where one dimension simply comes on top of the other. In that case, current economic circumstances and evaluations of future opportunities would be robust yet separate predictors of vote choice, implying that they are substitutes rather than direct moderators of each other.

The first visualization in Fig. 6 emulates the theoretical framework by showing predicted probabilities only for combinations of high/low income and positive/negative social opportunity perceptions. For example, the estimate corresponding to low-income/positive opportunity approximates an aspirational voter's voting behaviour. The three panels in Fig. 6 provide evidence of a partly reinforcing impact of our two explanatory variables. Panel (a) confirms our interpretation that the combination of high-income and positive opportunity perceptions markedly increases support for parties in government. The pattern regarding mainstream opposition support is less pronounced and does not suggest significant interaction effects (Panel b). When it comes to radical voting, Panel (c) confirms that opportunity perceptions are a key determinant of support. Clearly, voters with positive opportunity perceptions are much less likely to support radical parties, and this difference is even slightly accentuated among high-income voters.

Figure 6. Interaction income × Opportunity perception.

Figure 7 provides another illustration of the same interaction model by showing the slope of opportunity perceptions over the full range of respondents' income levels (measured in deciles). Again, the results suggest that the interaction of both dimensions is particularly relevant to explain incumbent voting. Positive opportunities significantly reinforce support for government parties but only among mid-to-high-income earners. The evidence with respect to mainstream opposition voting is weaker and not suggestive of a clear, interactive relationship between income and opportunity. Finally, we see that respondents with positive social opportunity evaluations on any income level are less likely to vote radical and particularly so if they are of higher socioeconomic status. One important implication that Figs 6 and 7 jointly provide is that higher socioeconomic status proxied by income levels cannot effectively compensate for the lack of positive opportunity perceptions when it comes to radical voting. The interaction models hence again highlight the societal and political relevance of the apprehensive voters who might feel attracted by anti-system appeals despite their relatively comfortable socioeconomic status.

Figure 7. Interaction income × Social opportunity perception (Continous).

Implications and Robustness

Our theoretical point of departure has led to a dependent variable that bundles parties with very different ideological profiles in the camp of radical parties. We might, of course, ask about the specific support for a radical right or radical left alternative to the political mainstream. The left/right distinction is likely to provide important insights regarding the mechanisms through which negative opportunity perceptions are mobilized. In line with the literature discussed above, we would expect apprehensive voters to turn specifically to radical right parties. The appeals of nativist-traditionalist radical right parties are supposed to resonate well with apprehensive voters because their negative perceptions of opportunities are likely to take the form of a more diffuse sense of unease with and rejection of broader economic and social change among these voters. Precisely because these apprehensive voters are well-off and often well-protected by the labour market institutions and welfare states in the countries we study, their sense of dislocation is unlikely to be fully mitigated by further material protection and compensation. Rather, as occupational status hierarchies, family models, gender roles, or children's mobility prospects change in the knowledge economy, forward-looking concerns related to social position, a sense of dignity and societal worth, and identity present a somewhat more obvious link to radical right parties’ programmatic profile.

From this reasoning follows the observable implication that our results should be particularly clear and strong for radical right parties. Figure 8 decomposes the mainstream and radical categories into left and right. Indeed, we see that aspirational and apprehensive voters differ clearly regarding radical right support (with apprehensive voters displaying higher support) but not regarding radical left support, where these groups are fairly average. While comfortable and burdened voters differ with regard to radical party support in general (and, unsurprisingly, regarding mainstream right support), the story of aspirational and apprehensive voters is clearly one about the radical right.

Figure 8. Average predicted probabilities of support for different party families.

Note: Probabilities are unweighted averages across all possible combinations of gender, class, education group, age group and country of residence. The baseline (white bars) are average predicted vote shares by party family across the entire sample.

We further probe the robustness and validity of our main results with various additional analyses. The following paragraphs provide a compact verbal summary; the respective Figs and Tables can be found in Appendix D.

As mentioned above, Fig. D.2 shows that our results do not depend on our classification of Green parties as mainstream parties. The main analysis results hold when treating Green parties (present in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden) as a separate party group. Next, Fig. D.3 shows that the pattern presented in Fig. 5 is even more pronounced if we look at ‘emblematic’ representatives of each of our quadrants rather than a respondent with averaged characteristics. In addition, we show in Fig. D.4 that the predictions visualized in Fig. 5 hold in a standard (multinomial) regression framework. We also demonstrate that our results do not hinge on a specific set of countries included in the analysis (Fig. D.5).

Next, we extend our admittedly simplistic dichotomous framework differentiating between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ voters by breaking average predicted probabilities down for three income levels (that is, for six different groups). Integrating a middle socioeconomic category allows for further refinements of these results. The main difference, however, is between high-income voters and the rest. The pattern among mid-income and low-income voters is relatively similar.

Finally, we exploit our detailed questionnaire to show that our results hold when looking at perceptions with respect to respondents' kids rather than their own prospects (Appendix Figs D.7 and D.9). The general pattern is very similar. We also show that we can recover most of our results with an item capturing opportunity perceptions that more specifically tap into prospects on labour markets rather than general social life chances (Appendix Figs D.8 and D.10). This alternative operationalization produces similar but somewhat weaker results, especially with regard to apprehensive voters. Their political grievances seem to be more strongly motivated by a generally negative view of social opportunities rather than their view of prospects at the workplace.

Electoral Coalitions in the Knowledge Economy

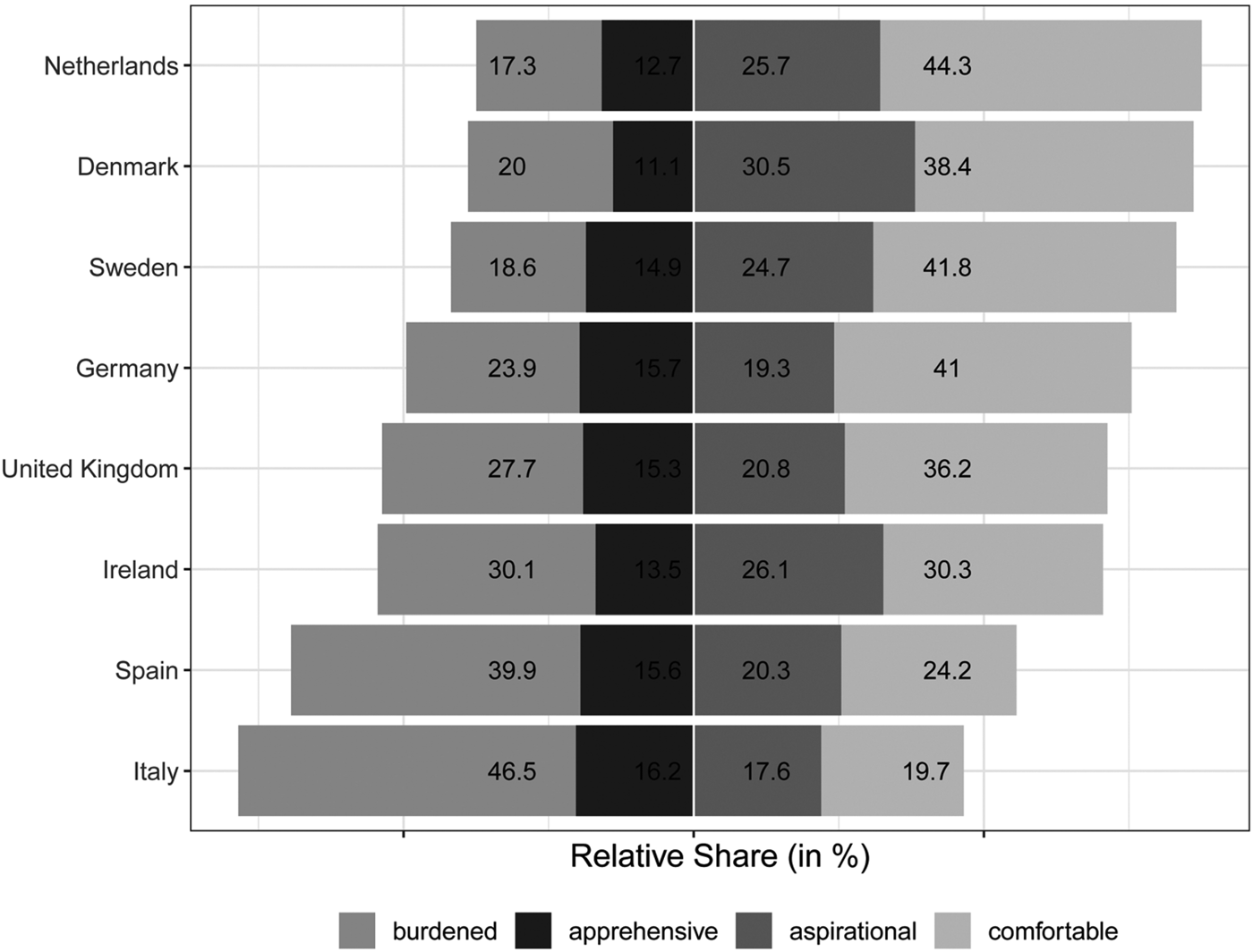

We have suggested a conceptual framework in which beneficiaries of post-industrial knowledge economies are understood not only on their objective socioeconomic standing but also on their subjective perception of future economic opportunities in a changing economy and society. As a direct implication of our analysis, the prospects of structural change and political stability depend on each of the four groups' relative size and political relevance. For example, suppose more confident pro-system forces, consisting of comfortable but also aspirational voters, dominate the democratic competition. In that case, modern knowledge economies have a fairly stable backing among the population and will be able to avoid potential disruption from the minority of voters who are and/or feel left behind by economic modernization. Figure 9 shows the relative importance of each of the four constituencies in each country under study.

Figure 9. Cross-national variation in relative importance of groups.

On average, the more confident coalition indeed clearly outweighs the pessimistic coalition. At the same time, however, the plot reveals striking variations in relative group sizes. Continental and Northern European countries are characterized by a large share of voters (60–70 per cent) who believe in economic opportunity for themselves and their children. However, voters in the European South show a much stronger prevalence of negative perceptions of economic opportunity. In both Italy and Spain, pro-system aspirational and comfortable voters represent a minority coalition. They are outnumbered by burdened and apprehensive voters who are relatively more likely to support radical parties. This pattern across countries is particularly telling given the fact that the Southern European countries, as well as Ireland, were on a striking path of economic upswing and recovery in the years leading up to 2018, the year of our survey. Unemployment fell sharply, and growth was robust after 2015 in these countries. Nevertheless, the share of voters with negative structural, long-term perceptions of opportunities is massive compared to the countries of Northern and Continental Europe. This pattern gives us further confidence that our concept and measure of opportunities is theoretically and empirically distinct from cyclical macro-economic performance but instead reflects a perception of structural performance, which then feeds into an assessment of whether the status quo should be radically challenged in political terms or not.

The relative strength of the four groups in Southern Europe represents a political configuration with much more limited support for creating and sustaining modern knowledge economies. However, this also points towards a potentially self-reinforcing dynamic, whereby less knowledge-based economies are less likely to create and sustain the electoral coalitions that might support pro-system agendas set to further deepen the knowledge economy within the existing framework. What is more, the share of burdened and apprehensive voters in the Southern European countries is so high that they even represent a relevant share of mainstream party electorates (around 50 per cent), whereas they are mostly confined to the more radical party constituencies in the Continental and Northern European countries (Appendix E)Footnote 5. Their impact on government formation and policies is even more likely, reinforcing the suggested self-reinforcing dynamics.

Conclusion

Widespread political disruption and the ascent of radical parties critical of the establishment in almost all advanced capitalist democracies have led to renewed interest in the structural determinants behind these electoral challenges to the political-economic status quo. The most recent body of work has produced a near consensus among scholars that studying voters' objective and immediate socioeconomic circumstances fall short of explaining radical or anti-establishment voting. Instead, researchers have highlighted the importance of relative, dynamic, and subjective perceptions of economic and social conditions. We add to this strand of research by demonstrating the electoral implications of prospective evaluations of economic opportunity for voters and their offspring.

Our empirical analysis provides robust evidence that prospective economic opportunity, net of objective material conditions, is an important channel through which radical political disruption works and can potentially be mitigated. ‘Aspirational voters’ who might not do well themselves but positively evaluate economic or social opportunities in the future, not least for their children, tend to be clearly less supportive of radical parties (but they may well support the mainstream opposition). To some extent, prospective economic opportunity and current material conditions represent substitutable factors that reduce the likelihood of supporting radical parties. Positive evaluations of opportunity could even mitigate the success and possibly the further rise of such parties. However, this prospect appears more tenuous in the long term when we consider the socio-demographic profile of aspirational voters: much appears to depend on whether this sizeable group characterized by its youth, mid-level education, and non-routine manual work in the service sector maintains high hopes for the future. Within the framework of advanced democratic capitalism, this depends largely on future growth and job creation to match continuing educational expansion. These macro-conditions can shape the subjective prospects of today's young aspirational voters and tomorrow's potentially aspirational youth. Disappointed status expectations could make people more prone than ever to vote for radical parties (Kurer and van Staalduinen Reference Kurer and van Staalduinen2022).

Another cautionary note regarding the potential of evaluations of opportunities to bolster support for the political mainstream concerns what we call ‘apprehensive voters’: We show that negative social and economic expectations are associated with higher support for radical parties even among well-off voters, suggesting that the aspirational voter argument might also be reversed. Well-off, apprehensive voters are highly susceptible to the appeals of radical parties, particularly the nativist-traditionalist appeals of radical right parties. Only the combination of both factors (high status and positive evaluations of opportunities) is associated with above-average support for mainstream incumbents. From the perspective of the political mainstream, it may be considered reassuring that the socio-demographic groups typically belonging to ‘apprehensive’ and also lower-income ‘burdened’ voters – routine workers, production workers, or the lower-educated – tend to be shrinking. Meanwhile, our ‘comfortable’ voters who staunchly support mainstream parties (especially incumbents) are made up of groups of knowledge workers that tend to be growing in the occupational structure. Our analyses at least indicate that young people, the highly educated and high-skilled voters, are not (yet) overly ‘apprehensive’ about their own and their children's future opportunities.

A key reason why we contend it is worthwhile investigating prospective evaluations relates to their policy implications: While nostalgic visions of the past may not be impossible to combat, people's prospective evaluations are arguably the more important political battleground: unlike retrospective views, parties have the chance of improving people's evaluations of opportunities not just by supplying narratives of promise and hope, but through policies that will have a tangible impact on people's lives. Hence, these findings obviously raise the question of which policies affect evaluations of future opportunities. If open education systems, social investment, and opportunities for social mobility affect these evaluations positively, this implies certain policy leverage to limit support for radical parties. Policies could even have a double effect on political preferences via perceptions of parents on the one hand and via both immediate economic circumstances and perceptions among their children on the other hand. The varying size of the aspirational voter group across the countries in our study indicates that some policy leverage may indeed exist for how younger voters, people with medium levels of education, or service sector workers view their future opportunities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000145.

Data availability statement

Replication materials for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/D2REB3

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, we would like to thank Mariana Alvarado, Peter Hall, Torben Iversen, Frieder Mitsch, Andrew McNeil, David Soskice, our editor at the BJPolS, and three anonymous reviewers, as well as participants of the ‘Populism and Capitalism’ Workshop in Konstanz, 2019, the ‘ERC Welfarepriorities/Unequal Democracy joint workshop’ in Zurich, 2019, of Harvard's ‘Seminar on the State and Capitalism since 1800’, 2021, of the ‘NORFACE Populism, Inequalities and Institutions closing keynote’, 2021, and of Harvard's Verba Lecture, 2021.

Author contributions

Silja Häusermann, Thomas Kurer, and Delia Zollinger are listed alphabetically, reflecting equal contributions to the article.

Financial support

We gratefully acknowledge support from the following funders: Silja Häusermann has received and acknowledges funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 716075, ERC-project WELFAREPRIORITIES); Thomas Kurer from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No. 185204), from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG German Research Foundation) under Germany's Excellence Strategy EXC-2035/1–390681379 and from the University of Zurich's Research Priority Program (URPP) ‘Equality of Opportunity’; Delia Zollinger from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Doc.CH Grant No. 188365)

Competing interest

None.