There has been an important impetus in the field of business ethics to justify why companies should pursue corporate beneficence (Bowie Reference Bowie1999, Reference Bowie and Frederick2010; Buchanan Reference Buchanan1996; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2004, Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Lea Reference Lea2004; Mansell Reference Mansell2013, Reference Mansell2015; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Strudler Reference Strudler2017). However, it has been typical to conceptualize initiatives concerning corporate beneficence as conflicting with the obligations that managers have toward shareholders (Arnold Reference Arnold2003; Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019; Bowie Reference Bowie1999; Friedman Reference Friedman1970; Friedman, Mackey, and Rodgers Reference Friedman, Mackey and Rodgers2005; Heath Reference Heath2014b; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2009a, Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Rodin Reference Rodin2005; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2010; Strudler Reference Strudler2017). In this article, I intend to show that you do not need to go beyond the paradigm of shareholder primacy to ground a good deal of the duties of beneficence that scholars in the field expect managers to fulfill in their corporate roles.

Two conceptual roadblocks have prevented scholars in the field of business ethics from recognizing this: first, a lack of clarity about the different varieties of beneficence, and second, a failure to recognize that the mandate to increase shareholder value, a mandate that does not have any explicit reference to morality, nevertheless imposes significant moral constraints on what managers are supposed to do on shareholders’ behalf. Let me briefly expand on each.

The discussion on the topic of beneficence in the literature of business ethics has suffered from what Wittgenstein called “a one-sided diet of examples” (Wittgenstein [1953] Reference Wittgenstein1967, §593). Discussions on corporate beneficence usually focus only on one specific type of the duty of beneficence (typically the wide duty of charity). However, as I will show in this article, there are structurally different types of duties of beneficence, and each of these imposes different demands. This fact has been obscured by the assumption that all duties of beneficence are “imperfect.” At the heart of the idea that a duty is imperfect is that it offers a certain amount of leeway. However, I will argue that to properly understand the demands imposed by duties of beneficence, one needs to distinguish between two different notions of “leeway” that are almost always conflated: discretion concerning whether to fulfill it and latitude in how one may fulfill it. Distinguishing between these two senses of leeway is critical to properly understanding the demands imposed by beneficence on shareholders and managers.

Scholars committed to shareholder primacy, in particular, to the view that managers should act on behalf of shareholders, often claim that managerial duties are exempt from duties of beneficence (Friedman Reference Friedman1970; Rodin Reference Rodin2005; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2000). Within this perspective, corporate beneficence has often been presented as a violation of the manager’s fiduciary duties to shareholders, even as a form of (altruistically motivated) theft (Friedman Reference Friedman1970; Minow Reference Minow1999; Rodin Reference Rodin2005; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2000; Strudler Reference Strudler2017). I will argue that there is some truth to this view: to the extent that managers act on behalf of shareholders, they are not required to fulfill (and may sometimes be prohibited from fulfilling) “wide duties of beneficence,” that is to say, duties of beneficence that afford discretion and latitude. However, what these scholars miss is that such managers are nevertheless required to fulfill “narrow duties of beneficence,” that is, duties of beneficence that do not afford latitude. Furthermore, because some of these narrow duties do not afford discretion, they should actually be conceptualized as perfect duties of beneficence.

As such, this article makes two important contributions to the field: 1) it refines our understanding of the duty of beneficence (and, by way of this, of imperfect duties more generally), and 2) it sheds light on the duties of beneficence that are imposed on managers who act on behalf of shareholders. Because most of the arguments I provide rely only on the abstract relationship between agents/trustees and principals/beneficiaries, it can be seen as providing a blueprint for analyzing the duties that bind managers who act on behalf of a wider set of stakeholders beyond just shareholders.

The article contributes to our understanding of the moral duties that apply to managers in their corporate capacity. It is not concerned with legal questions concerning whether duties of beneficence are required or forbidden by law or prudential questions concerning the way in which beneficence affects the company’s bottom line or its long-term success.

One may justify duties of corporate beneficence in many different ways. My aim here is not to offer a definitive or superior justification but rather to show that the agency relationship between managers and shareholders is sufficient to ground a wide variety of duties of corporate beneficence that business ethicists expect managers to discharge.

Finally, when one discusses perfect and imperfect duties, audiences typically assume that one’s theoretical background is Kantian. This is unwarranted. Although Kant is the most prominent scholar associated with this distinction, such a distinction predates him (Schneewind Reference Schneewind1990). The arguments put forth in this article rely not on the Kantian theoretical apparatus but on a strong pretheoretical intuition that belongs to what one may call “ordinary morality.” As such, the article is meant to operate within a thin normative framework that is compatible with the views held by most moral philosophers.

The first two sections of the article provide its theoretical framework. Section 1 describes the normative principles that should guide one to identify the obligations that bind managers who act on behalf of shareholders. Section 2 discusses the most important features of the duty of beneficence, explains why it has been typically conceptualized as an “imperfect duty,” explores a variety of misconceptions in the literature about its nature, and distinguishes two types of leeway associated with its “imperfect” nature: discretion and latitude.

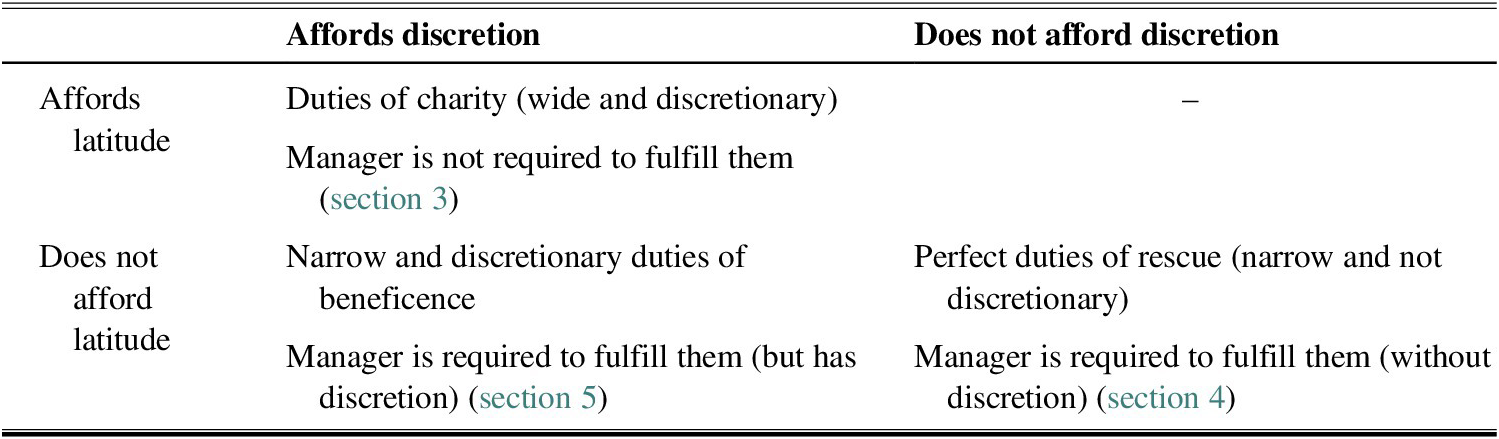

Section 3 focuses on the wide duty of charity, the paradigmatic duty of beneficence, a duty that offers both latitude and discretion. I argue that the manager is not required to fulfill (and may actually be forbidden from fulfilling) duties that allow for discretion and latitude. Section 4 discusses duties of rescue that offer no discretion and no latitude and that, I argue, should be recognized as perfect duties of beneficence. Finally, section 5 discusses duties of beneficence that afford discretion but don’t offer much latitude. I argue that the manager is required to fulfill narrow duties of beneficence (without discretion in the former case and with discretion in the latter). Table 1 (section 2.3) condenses this taxonomy and maps out to the different sections of the article.

1. MANAGERS ACTING ON BEHALF OF SHAREHOLDERS: A NORMATIVE APPROACH

1.1 Managers Acting on Behalf of Shareholders

Numerous scholars have defended the view that managers are meant to act on behalf of shareholders (Friedman Reference Friedman1962, Reference Friedman1970; Goodpaster Reference Goodpaster1991; Hansmann and Kraakman Reference Hansmann and Kraakman2001, Reference Hansmann, Kraakman, Rasheed and Yoshikawa2012; Heath Reference Heath2011; Hessen Reference Hessen1979; Jensen and Meckling Reference Jensen and Meckling1976; Kaler Reference Kaler2003; Langtry Reference Langtry1994; Mansell Reference Mansell2013, Reference Mansell2015; Marcoux Reference Marcoux2003; McMahon Reference McMahon1981; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2000, Reference Sternberg2010; Von Kriegstein Reference Von Kriegstein2015).Footnote 1 There are two main ways in which scholars spell out this idea. The first, often favored by economists and some moral philosophers, is to conceptualize the manager as the agent of shareholders. The second, often favored by legal scholars and some moral philosophers, conceives of managers as fiduciaries, stewards, or trustees of shareholders. In the first, the manager is meant to be directly answerable to shareholders. In the second, the manager administers the company in their interest even if she is not directly answerable to them. Common to both perspectives is that the manager has been delegated authority to act on behalf of the principal.Footnote 2 In what follows, I use the term agent in a broad sense to refer to a person who acts on behalf of another, a broad usage that encompasses the case where the agent is directly answerable to shareholders or where she acts as their fiduciary/trustee.Footnote 3

1.2 Normative Managers and Shareholders

To the extent that managers are meant to administer the company on behalf of shareholders, the managerial decision-making process should be guided by the question: “Is this what shareholders would want the manager to do on their behalf?”Footnote 4 Because our investigation in this article is normative, this question should be addressed from a normative perspective. From such a perspective, the claim that managers are required to do “what shareholders would want” should not be construed as an empirical question of what actual shareholders effectively want. It is a normative question that implies moral scrutiny of, and in turn possible limits upon, “what shareholders are entitled to want.”Footnote 5

Failing to recognize this leads to an untenable moral view of the agency relationship. When a manager acts on behalf of a shareholder, she is guided by the fundamental principle qui facit per alium (he who acts through another acts himself). Among the implications of such a principle is that the obligations of the manager do not override the moral obligations of shareholders or allow behavior by managers that would be prohibited to shareholders (Goodpaster Reference Goodpaster1991; Von Kriegstein Reference Von Kriegstein2016). Built into any agency relationship is the fact that there are moral limits on what principals can demand from their agents. An agent is not allowed to pursue an action on behalf of a principal that would be morally prohibited for the principal to pursue on her own. Consequently, to think of shareholders in normative terms involves thinking that, even if their motivations may be driven by self-interest, such motivations need to be constrained by morality. Thus, from a normative perspective, the decision-making process of managers should be guided by the following:

Guiding managerial question: Is this what moral shareholders would want the manager to do on their behalf?

1.3 Caveats and Potential Objections

One may worry that my account is unrealistic because it assumes that all shareholders abide by moral norms. This worry is displaced because my aim here is not empirical but normative; it is not to identify how individuals effectively act but to articulate how they should act.Footnote 6

One may also have worries of whether this normative approach is consistent with principles of fiduciary law that appear to forbid fiduciaries from 1) imposing normative views of their own on their managerial practices and 2) favoring the interests of one group of shareholders (normative or otherwise) over those of another group of shareholders. This objection is misguided. It is a misunderstanding of the nature of morality to think that when the manager acts within moral constraints, she is imposing her own views on shareholders. It is a similar misunderstanding to think that “normative shareholders” are a special kind of “interest group.” What differentiates normative shareholders from all the others is that they want the manager to act as morality dictates. A group constituted by shareholders who are not “normative shareholders” is a group who wants the manager to pursue immoral business practices. If fiduciary law forbids favoring the interests of normative shareholders over the interests of other shareholders, such a law would encourage immoral behavior and should, thereby, be reformed.

2. BENEFICENCE

In this section, I provide a basic sketch of the most important features of the duty of beneficence, explain why it has been typically conceptualized as an “imperfect duty,” and discuss a variety of misconceptions in the literature about its nature. I conclude by offering two main distinctions, latitude and discretion, that will help us identify the duties of beneficence that bind managers who act on behalf of shareholders.

2.1 An Overview

The duty of beneficence is concerned with norms, actions, and dispositions whose ultimate aims are to promote the good of others, quite often in the form of alleviating their suffering (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019). Beneficence, however, is not merely “wishing well”; it involves “active practical” steps to further the benefit of others (Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018, 6). Not all activities where we promote the good of another person are instances of beneficence. For my action to be grounded on the duty of beneficence, my ultimate goal has to be the promotion of this person’s good or the alleviation of her suffering. Helping a person in need with the ultimate aim to make a good impression is not an instance of beneficence. “Corporate beneficence” aimed at increasing the financial returns of shareholders or the company’s reputation is also not an instance of beneficence (Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018, 3–4; Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006, 200–201; Rodin Reference Rodin2005, 175).Footnote 7

While there is considerable disagreement in the scholarship about the magnitude of the sacrifices that beneficence requires of us,Footnote 8 there is widespread agreement that 1) a moral agent ought to be beneficent, but 2) the demands of beneficence should not be overly demanding (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019; Buchanan Reference Buchanan1996; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Hill Reference Hill1971; Hsieh Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Miller Reference Miller2004; Schmitz Reference Schmitz2000). The first claim is often grounded in the fact that our shared humanity requires us not to be indifferent to the suffering of others (Herman Reference Herman1993; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012; Stohr Reference Stohr2011). The second is grounded in the acknowledgement that each of us is entitled to a certain degree of partiality toward ourselves, to give our own projects and well-being a certain priority (Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Schmitz Reference Schmitz2000; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012).

2.2 Imperfect Duties of Beneficence

There are conceptual difficulties to offer a satisfactory characterization of the duty of beneficence, difficulties that have led to confusion in the literature of business ethics. At the heart of these difficulties is the fact that while beneficence is a duty (and therefore obligatory), it allows for discretion (so that we can pursue our own personal projects and well-being). These two commitments appear to be in tension; the duty’s discretion appears to undermine its mandatoriness (cf. Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012, 61–62).

Scholars have usually appealed to the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties to address this tension (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019; Bowie Reference Bowie1999, Reference Bowie and Frederick2010; Buchanan Reference Buchanan1996; Cummiskey Reference Cummiskey1996; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1992; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Herman Reference Herman1993; Hill Reference Hill1971; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2017b; Kaler Reference Kaler2003; Lea Reference Lea2004; Mansell Reference Mansell2013, Reference Mansell2015; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Rainbolt Reference Rainbolt2000; Schroeder Reference Schroeder2014; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012; Stohr Reference Stohr2011; White Reference White and White2019). Their shared use of terminology may suggest a certain uniformity in their approach, but this uniformity is merely apparent. The labels “perfect” and “imperfect” occlude a wide variety of (often inconsistent) uses of these terms.

When applied to duties that one party has to another, the labels “perfect” and “imperfect” have been used to distinguish whether the duty is negative or positive (Buchanan Reference Buchanan1996); whether it requires concrete and specific actions or the adoption of general ends, principles, or maxims (de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Hill Reference Hill1971; Kant Reference Kant and Gregor1998; Mansell Reference Mansell2013; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Stohr Reference Stohr2011); whether the other party is (or is not) owed the duty and has (or does not have) a right to demand that the duty be discharged (Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Kaler Reference Kaler2003; Lea Reference Lea2004; Pufendorf [1672] Reference Pufendorf, Oldfather and Oldfather1964); whether the duty’s violation requires us to “think a contradiction” or merely to “will a contradiction” (Bowie Reference Bowie1999; Herman Reference Herman1993; Kant Reference Kant and Gregor1998; Lea Reference Lea2004); whether the duty can (or cannot) be the basis for state legislation (Lea Reference Lea2004; Mansell Reference Mansell2013; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012); whether the duty allows (or does not) one to be excused from fulfilling it by appealing to one’s inclinations (de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Herman Reference Herman1993; Hill Reference Hill1971; Kant Reference Kant and Gregor1998); and whether the duty’s fulfillment is stringent or whether it allows for latitude concerning how, when, and whom to benefit (Buchanan Reference Buchanan1996; de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1992; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Hill Reference Hill1971; Hsieh Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Kant Reference Kant and Gregor1998; Lea Reference Lea2004; Mansell Reference Mansell2013; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Rainbolt Reference Rainbolt2000; Schroeder Reference Schroeder2014; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012; Stohr Reference Stohr2011).

A cursory look at the variety of these distinctions shows that they do not all carve conceptual space in the same way and, therefore, that they do not all track the same distinctions (Rainbolt Reference Rainbolt2000).Footnote 9 To clarify the nature of duties of beneficence, I will start by discussing two important confusions in the scholarship of business ethics concerning their “imperfect” nature.

The first confusion concerns their obligatoriness. It has been argued that because duties of beneficence allow for discretion, they are merely optional and, therefore, should not be considered a duty at all (Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Ross Reference Ross1954). This argument is mistaken; it is attempting to shoehorn all duties into the mold of perfect duties. As such, this argument fails to see that duties can be obligatory in more than one way. Even if the duty of beneficence allows for discretion about how to fulfill it, it is nevertheless obligatory (cf. Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018, 7). The distinction between types (i.e., classes) and tokens (i.e., particular instances of that class) helps to shed light on the issue. As a type, both perfect and imperfect duties are obligatory. But whereas every token of a perfect duty is also obligatory, this is not the case with imperfect duties. One has discretion to determine whether to fulfill a token of an imperfect duty; when faced with a specific situation where one has an opportunity to discharge an imperfect duty, one is not necessarily required to discharge it.

This does not entail that discretionary duties are optional or involve minimal commitment. Although we are not required to “act on the duty of beneficence all the time” (Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018, 7), we would be failing to fulfill this duty if we never acted on it or if our willingness to fulfill it were lukewarm (cf. Herman Reference Herman1993). Beneficence is a duty because it demands a serious and continuous commitment to promoting the good of others (Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018, 11; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012). It follows, contra Ohreen and Petry (Reference Ohreen and Petry2012, 369), that beneficence is not optional and that the extent of one’s beneficent commitment matters; doing too little or failing to identify the duty’s demands on different circumstances shows that one is not fulfilling this duty.

A second important confusion in the literature on business ethics associated with imperfect duties has resulted from an influential characterization by Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1996). In an otherwise excellent paper, Buchanan suggests that to combat the moral laxity that imperfect duties open us to, we should “perfect” them by taking determinate steps to make sure that we fulfill them (31–32). This phrasing has led to a conceptual confusion among several scholars in the field (see, e.g., Lea Reference Lea2004; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012). While we should agree with Buchanan on the importance of taking definite steps to ensure that one fulfills one’s imperfect duties, it is a conceptual mistake to think that, when one does this, imperfect duties become perfect. The fact that one has taken determinate steps to fulfill, say, the duty of charity does not mean that the structural way in which this duty requires us to fulfill it has changed. To use “perfect” and “imperfect” to carve out whether one has (or does not have) a specific plan of action to fulfill a duty is to confuse the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties with the distinction between having a clear plan of action and not having one.

2.3 Discretion and Latitude

Although business ethicists have recognized that duties of beneficence allow for leeway (Buchanan Reference Buchanan1996; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1992; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Hsieh Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Lea Reference Lea2004; Mansell Reference Mansell2013; Mejia Reference Mejia2019; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Rainbolt Reference Rainbolt2000; Schroeder Reference Schroeder2014), they have not distinguished between two important and structurally different types of leeway that I will call discretion and latitude.

Discretion: Although the duty of beneficence makes demands on us, these demands are meant to be sufficiently lenient to allow us to pursue our personal projects and well-being. In allowing for such leniency, the duty is meant to make room, not merely for my fundamental needs and rights, but also for my inclinations, passions, and sensibilities. As Hill (Reference Hill1971, 59) remarks, we are justified to “sometimes pass over an opportunity to make others happy simply because we would rather do something else” (cf. White Reference White and White2019). I will say that a duty of beneficence offers discretion if it allows the agent to appeal to her inclinations, passions, and sensibilities to determine whether to fulfill the duty on a particular occasion. I will sometimes refer to this discretion as subjective discretion to highlight that what explains whether or not the agent fulfills the duty may depend on her subjectivity, that is, on her inclinations, passions, and sensibility.

Latitude: I will say that a duty of beneficence offers latitude if it allows for a wide variety of ways to fulfill it, in terms of how the duty is to be fulfilled, when it should be fulfilled, and whom it should benefit. I will say that a duty is wide if it affords latitude and narrow if it does not.

The distinction between duty types and duty tokens helps to clarify the preceding distinction. Discretion tells you whether you have leeway to fulfill a particular duty token. Once you’ve decided to fulfill a duty token, latitude indicates how much leeway you have in how you effectively discharge it. Having discretion concerning whether to fulfill a duty is different from having latitude concerning when to fulfill a duty. The former has to do with a decision about whether a particular duty token should be discharged, the second with when a duty token you have already decided to fulfill should be carried out.

A duty may afford much discretion but little latitude. Imagine a stranger asking for directions in a foreign country where passersby do not speak his language. You speak his language and overhear him. You have a duty to help (this duty type is obligatory); if you never help in these kinds of cases, you would be callous and could not be said to fulfill the duty of beneficence instantiated here. But this duty affords discretion because you are not obligated to discharge this duty token. A variety of reasons, many related with subjective considerations, may justify passing on this opportunity to help. Suppose now you decide to help. Once you have decided to discharge the duty on this particular occasion (this duty token), you have little latitude in terms of how you ought to fulfill it (you ought to provide directions), when you are to help (the directions are needed now), or whom you should benefit (you need to help the foreigner).

Within business ethics, research into duties of beneficence has typically been approached in a binary fashion. Scholars in business ethics have often argued either that managers are or are not bound by duties of beneficence. As I will show in this article, we need a more granular approach to understanding the duties that managers need to discharge when they act on behalf of shareholders. In the next sections, I examine three families of duties of beneficence that are structurally different: duties of charity that are wide and afford discretion (section 3), perfect duties of rescue that do not offer discretion or latitude (section 4), and duties of beneficence that are narrow but allow for discretion (section 5). Table 1 offers an overview of the conceptual landscape that we will explore.

Table 1: Latitude and Discretion in Duties of Beneficence

Note. Discretion allows the agent to determine whether to fulfill the duty in a particular occasion. Latitude allows for leeway in terms of how the duty is to be fulfilled, when it should be discharged, and whom it should benefit.

3. WIDE DUTIES OF BENEFICENCE THAT AFFORD DISCRETION

3.1 Do Wide Duties of Charity Bind Shareholders?

The wide duty of charity, which is typically fulfilled by making a financial contribution to a charitable organization, is perhaps the paradigmatic example of a duty of beneficence. This duty affords the agent not only discretion to decide whether to fulfill the duty in any particular circumstance but also latitude concerning how, when, and whom to benefit.Footnote 10

To assess whether the manager needs to fulfill an obligation when she is acting on behalf of shareholders, one needs first to establish that this obligation arises in the context of the activities that the manager conducts on behalf of shareholders (Marcoux Reference Marcoux2003; Von Kriegstein Reference Von Kriegstein2016). Arguably, the duty of charity arises in the context of shareholders’ joint venture, at least when the company in which they have invested is financially successful. The fact that shareholders are increasing their wealth through their investment brings with it a moral obligation to share some of their proceeds with those who are less fortunate. Thus, at least when the business is financially successful, shareholders have a moral obligation to fulfill the wide duty of charity.

Some scholars in the field have suggested that, when all shareholders are bound by a particular obligation, the manager who is acting on their behalf is required to fulfill it (Goodpaster Reference Goodpaster1991, 68; Mansell Reference Mansell2013, 596; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012, 368; Von Kriegstein Reference Von Kriegstein2016, 446). Goodpaster (Reference Goodpaster1991, 68), for instance, has claimed, “The conscience of the corporation is a logical and moral extension of the consciences of its principals.” Mansell (Reference Mansell2013, 596) has argued that “if shareholders have a ‘duty of beneficence’ to make the interests of non-shareholders their end, then ipso facto these interests become part of the corporate objective.” While this may seem like a natural conclusion to draw, it is mistaken. The fact that every shareholder is bound by an obligation does not necessarily entail that this obligation should be fulfilled by their agent. An obligation that falls on shareholders should only be fulfilled by the manager if (moral) shareholders would want her to fulfill it on their behalf. There are, of course, cases where shareholders may have explicitly or tacitly agreed to this.Footnote 11 However, barring such explicit or tacit agreement, there are compelling reasons to think that shareholders who live up to what morality requires may not want the manager to fulfill the wide duty of charity on their behalf.

3.2 Why Shareholders May Not Want to Fulfill Their Duty of Charity through Their Manager

Not requiring the manager to do charity (i.e., a wide discretionary duty) on behalf of shareholders may be seen as warranted, even morally warranted, because 1) this is a personal matter into which managers have no insight and 2) this allows shareholders to better express themselves morally.

3.2.1 A Personal Matter

As I discussed earlier, it is typically taken for granted that, in deciding how to fulfill one’s duty of charity, every individual person is supposed to be guided by his own inclinations and subjectivity, as well as by his specific financial situation. If a shareholder’s inclinations and sensibility incline him to help children, he will want to focus his beneficent efforts on initiatives that help children. But if his inclinations and sensibilities incline him to help the elderly then he may focus his beneficent efforts on serving elders. A shareholder’s financial situation may also impose different constraints concerning how much he is supposed to contribute. Wealthier individuals are expected to contribute more to charity than those less well-off (Lea Reference Lea2004, 214–15).

Thus, discharging the duty of charity depends on shareholders’ own inclinations and personal circumstances. In most managerial decisions, the manager is better positioned than shareholders to know or decide how to allocate corporate resources. This is not the case with the duty of charity that binds shareholders. If the manager has to decide how to fulfill this duty on shareholders’ behalf, she has to attend, not to the business and its needs, but to shareholders’ individual subjectivities and personal circumstances. Because how a shareholder fulfills the duty of charity is closely tied with individual considerations about each shareholder, it is typically outside of the scope of the managerial responsibilities (unless, of course, shareholders have agreed, either tacitly or explicitly, to have the manager discharge this duty on their behalf).

3.2.2 Respecting the Moral Freedom and Moral Autonomy of Shareholders

Different authors in the literature have recognized that wide duties of charity provide agents with a space to express themselves morally. Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1996, 30), for instance, mentions that the wide latitude afforded by discretionary duties “allows us to pick our moral battles.” Similarly, Lea (Reference Lea2004, 210) claims that such latitude preserves agents’ freedom, individual autonomy, and “moral choice.” Finally, Rainbolt (Reference Rainbolt2000, 248) has argued that by giving us the latitude to decide whom to help and how to help, the duty of charity allows us to exercise “moral freedom” by offering us a space to express ourselves morally.

When a manager fulfills the duty of charity on behalf of shareholders, she is actually constraining their ability to express themselves morally in this way (unless shareholders have exercised this autonomy by agreeing, either tacitly or explicitly, to have the manager fulfill this duty on their behalf). Thus the manager’s refusal to fulfill the duty of charity on behalf of shareholders is not merely morally justified; it is morally recommended when it is a manifestation of her recognition of the autonomy and freedom of shareholders to express themselves morally.

3.3 Objections and Caveats

3.3.1 Aren’t Shareholders, in This View, Morally Callous?

It may be objected that by claiming that shareholders will not want the manager to fulfill the duty of charity on their behalf, I end up portraying such shareholders as morally callous. This objection is misguided. I am not denying that shareholders are obligated and should be committed to fulfilling the duty of charity. All I am saying is that, because this duty affords wide latitude, shareholders are not required to fulfill it through the company in which they have invested. If shareholders adequately fulfill their duty of charity individually, their moral standing need not be compromised, and the attribution of “callousness” is misguided.

Of course, what I have said is not meant to discourage shareholders from coordinating efforts to fulfill their duty of charity through their joint venture. It is meant to show that coordinating such efforts is not morally required and that not trying to do it need not be morally objectionable.

3.3.2 Subjective Discretion, Needs, and Efficiency

The claim that shareholders should have subjective discretion to determine how to fulfill their wide duties of charity does not entail that the fulfillment of such a duty should be responsive only to their subjective preferences. Beneficence should not be guided merely by the personal preferences of the giver; it should also be guided by the actual needs of the potential receivers. Thus, the subjective discretion that the duty affords cannot be untethered from the needs of those whom the beneficent deeds are meant to serve. Moreover, the subjective latitude concerning how, when, and whom to help has to take into account considerations about impact, effectiveness, and efficiency. As I discussed earlier (section 2), beneficence is not merely “wishing well.” It has to involve “active practical” steps to further the benefit of others. These steps involve the person’s reflection and responsiveness to issues concerning the impact, effectiveness, and efficiency of her beneficent deeds.

3.3.3 The Limits of My Argument

In this section, I have shown that you cannot ground the manager’s obligation to fulfill the duty of charity on the principal–agent relationship between manager and shareholders. My argument is limited to the duties that emerge from the principal–agent relationship alone. It is open to scholars to argue that managers have additional beneficent obligations beyond these. For instance, one might argue that the government provides certain benefits to companies in exchange for which the company is obligated to give back to society in the form of charitable contributions (Ciepley Reference Ciepley2013; Ireland Reference Ireland1999); that by incorporating as a company, the company acquires corporate agency and, with it, has the same obligations that apply to human persons (Hsieh Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012); or that managers’ fiduciary duties are limited to generating reasonable financial returns for shareholders, but that the manager is required to pursue corporate charity with the surplus from these returns (Lee Reference Lee2020; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Strudler Reference Strudler2017).

3.3.4 Effective Altruism

Defenders of effective altruism are likely to object to the account of charity that I offered in this section.Footnote 12 In particular, they may object that beneficence should not include considerations about the personal idiosyncrasies of the giver but should be based exclusively on the particular needs of the recipients and the overall amount of good that can be done. The objector would argue that we should not be given latitude to decide how to fulfill our duty of beneficence and should, instead, seek the way to do charity that creates the most good.

My aim in this article is to offer a taxonomy that organizes what diverse scholars in the literature of business ethics have said about beneficence and to use this account to articulate which of these duties bind managers when they act on behalf of shareholders. As such, my aim is not to determine which account of beneficence is superior but to articulate what each of these accounts entails for the corporate duties of beneficence that managers, qua agents of shareholders, are required to fulfill.

Most business ethicists agree that the duty of charity affords discretion and latitude, and I have shown that, when charity is conceptualized in this way, the principal–agent relationship between shareholders and managers does not require managers to fulfill (and in some cases even forbids them from fulfilling) this duty on behalf of the shareholders. But those who endorse effective altruism deny that charity affords latitude and, thereby, conceptualize all duties of charity as narrow duties. What are the managerial obligations in this case? The next two sections flesh this out. In section 4, I discuss narrow duties of beneficence that afford no discretion. In section 5, I investigate narrow duties of beneficence that do afford discretion.

4. NARROW DUTIES OF BENEFICENCE THAT AFFORD NO DISCRETION

Because the wide duty of charity has been the paradigmatic example of the duty of beneficence, and because of the central stage that this duty has occupied in the literature, scholars have tended to conceptualize all duties of beneficence on its likeness. With few exceptions (de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1992; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012), business ethicists tend to think that norms concerning beneficent activities should be voluntary and, consequently, that duties of beneficence should be characterized as imperfect.

My two main aims in this section are 1) to show that some duties of beneficence should be conceptualized as perfect duties and 2) to show that fulfilling these obligations is something that managers are required to do when they are conducting the company on shareholders’ behalf.

4.1 A Drowning Child

Let me start by discussing perfect duties of beneficence in general before focusing on the corporate case. Singer (Reference Singer1972) offered a powerful example to motivate the intuition that some duties of beneficence should be conceptualized as perfect duties:

Drowning: A passerby is walking past a child who is drowning in a small pond. All it takes for the passerby to save the child is the inconvenience of getting her clothes muddy. There is nobody around; if she does not save the child, the child will drown.

Nearly every scholar who has discussed this example agrees that, in this case, the agent does not have any subjective discretion to decide whether or not to rescue the child (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019; de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1992; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006; Herman Reference Herman1993; Hill Reference Hill1971; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2009a, Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Scanlon Reference Scanlon1998; Schmitz Reference Schmitz2000; Schroeder Reference Schroeder2014; Singer Reference Singer1972; Stohr Reference Stohr2011). Fulfilling this duty of rescue does not afford much latitude either, since what the rescuing agent is supposed to do is pretty narrow in terms of what to do, when to do it, and whom to help. Given that this duty affords neither subjective discretion nor latitude, it should be conceptualized as a “perfect” duty.

Scholars have pointed to at least four features of this situation that, in combination, account for why this situation does not leave room for subjective discretion (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019; de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Donaldson Reference Donaldson1992; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006; Herman Reference Herman1993; Hill Reference Hill1971; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Rainbolt Reference Rainbolt2000; Scanlon Reference Scanlon1998; Schroeder Reference Schroeder2014; Singer Reference Singer1972; Stohr Reference Stohr2011):

1. Grave consequences: There are grave consequences for the victim if he does not get rescued.2. Minor sacrifice: The sacrifice required of the rescuing agent is minor.3. Ability: The rescuing agent has the required abilities and capacities to rescue the victim.4. Uniquely well-placed agent: The agent is uniquely placed to aid the victim.

As I argued earlier (section 2), an inherent tension is built into the duty of beneficence, a tension between furthering the good of our fellows and pursuing our personal projects and well-being. Grave consequences and minor sacrifice reflect the two poles of this tension. Their combination amounts to the claim that, when there is a significant disproportionality between the grave consequences that would otherwise ensue for the victim and the minor sacrifices that the rescuing agent is required to make, the duty of rescue becomes strongly binding. The third secures the conditions of possibility for its exercise, and the fourth ensures that the duty is stringent by establishing that the agent is uniquely placed to provide help.Footnote 13

4.2 Perfect Corporate Duties of Rescue

In a seminal paper, Dunfee (Reference Dunfee2006) drew parallels between instances like Drowning and corporate examples where a company has the possibility to help victims of a catastrophe with limited financial sacrifices for shareholders. Business ethicists have disagreed with some of the specifics of Dunfee’s account (de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Dubbink Reference Dubbink2018; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2009a). My interest is not to lay out the precise conditions to ensure that a duty of rescue is or is not discretionary but to establish the existence of perfect duties of beneficence, duties of beneficence that afford no discretion and no latitude. For this purpose, I will appeal to what is, arguably, a less controversial example that aligns closer with Drowning and is not liable to the charges that have been raised against Dunfee’s examples:

Earthquake: A country is devastated by an earthquake, and thousands of local residents need blood transfusions. The branch of a highly profitable multinational company that has an important footprint in this country has the capacity to provide and distribute blood on a short-term basis to residents. This operation poses little risk to the company and is not particularly costly. Although the country’s geography is difficult to navigate, the company has unique access to a network of medical workers that know the country’s difficult geography and can do the transfusions. No other organization has the competency to provide and distribute the required blood. If the company does not act, thousands of people will die.Footnote 14

This example fits all four criteria discussed with respect to Drowning:

1. Grave consequences: There are grave consequences for the victims if the company does not provide aid (thousands of people would die).

2. Minor sacrifice: The multinational is highly profitable, and providing aid poses few risks. The sacrifice required from shareholders would be minor.

3. Ability: The company has the ability to provide aid on a short-term basis, given its footprint in the country.

4. Uniquely well-placed agent: The company is the only one with the ability to provide and distribute blood on a short-term basis, an ability that neither the government nor any other company has.

4.3 The Manager Is Required to Fulfill It

Hsieh (Reference Hsieh2009a) claims that Dunfee (Reference Dunfee2006) accounts for our intuition that companies should be held responsible for alleviating human misery, “even if at the expense of shareholder interests” (Hsieh Reference Hsieh2009a, 554). His claims echo a standard view in the literature, namely, that fulfilling corporate duties of beneficence, including the perfect duty of rescue, is not an instance of their acting on behalf of shareholders and actually violates the duties that managers have toward them (Arnold Reference Arnold2003; Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019; Bowie Reference Bowie1999; de los Reyes Reference de los Reyes2019; Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006; Friedman Reference Friedman1970; Friedman, Mackey, and Rodgers Reference Friedman, Mackey and Rodgers2005; Heath Reference Heath2014b; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2009a, Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Minow Reference Minow1999; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2010; Strudler Reference Strudler2017). This, as I will now argue, is a mistake. Fulfilling the perfect corporate duty of rescue is something that the manager is required to do because she is acting on behalf of (moral) shareholders.

I argued in section 1 that the manager’s decision-making process should ultimately be oriented by the question, is this what moral shareholders would want managers to do on their behalf? Let’s apply it to this case. The company is uniquely placed to remedy a very grave situation; thousands of lives would be saved if the manager were to provide aid on shareholders’ behalf; the sacrifices involved are minor for the company (and therefore to its shareholders) since it is highly profitable and providing aid does not pose significant risks to it; and the company has the competency to provide aid. If shareholders do not want the manager to provide aid and the manager complies with what they want, thousands of people will die. It should be obvious that shareholders who abide by what morality recommends would want the manager to provide aid on their behalf (cf. Brophy Reference Brophy2015).

Unlike with wide duties of charity, shareholders cannot fulfill this duty on their own because they do not have access to the resources and know-how needed to provide aid. Even if an individual shareholder volunteers to donate blood, this blood would not be readily available on a short-term basis. Moreover, no individual shareholder has the access and knowledge required to navigate the country’s difficult geography and do the transfusions in the area. Only the company, which the manager administers on shareholders’ behalf, has the capability to aid the victims. Because of this, shareholders cannot fulfill this duty on their own but need to fulfill it through their company. Consequently, the manager is obligated to discharge this duty on their behalf.

I conclude with a caveat similar to the one discussed in section 3.3.3. Some scholars think that managers should fulfill these perfect duties of rescue regardless of their fiduciary duties to shareholders. My argument is not meant to challenge (or support) this view. My aim is merely to show that one can ground this managerial duty solely in the principal–agent relationship.

5. NARROW DUTIES OF BENEFICENCE THAT AFFORD DISCRETION

In section 3, I argued that the manager is not required to fulfill wide duties of beneficence, such as charity, that afford discretion and latitude. In section 4, I showed that the manager is required to fulfill duties of beneficence, such as perfect duties of rescue, that offer no discretion and no latitude. I conclude the article by turning my attention to discussing the managerial responsibilities concerning narrow discretionary duties of beneficence, that is, duties that afford discretion but no latitude.

I start the section by discussing two examples of such duties: discretionary duties of rescue and discretionary duties to business partners. I argue that although the manager is required to fulfill them, she has discretion to determine, on particular occasions, whether or not to fulfill them. I then discuss the structural differences and similarities between discretionary duties of rescue and discretionary duties to business partners, articulating more generally why narrow duties of beneficence carry over from shareholders to managers. After elaborating on the decision-making strategies that the manager should deploy in deciding whether to fulfill narrow discretionary duties, I conclude by applying the framework I have developed to one of the most widely taught and discussed cases in the business ethics literature: Merck’s donation of Mectizan, an effective drug to cure river blindness.

5.1 Discretionary Duties of Rescue

Four conditions in Earthquake justified the fact that the duty of beneficence did not afford discretion: 1) grave consequences, 2) minor sacrifice, 3) ability to provide aid, and 4) uniquely well-placed agent. As you relax these conditions, the demands on the rescuing agent become less stringent. If the sacrifices and risks to the company are not minor (say, because they involve significant investments, long-term commitments, or significant legal or reputational risks), if the victims’ needs are not as grave (say, if these needs concern victims’ overall well-being but not their basic needs), and if the company is not uniquely placed and its competencies not so clearly aligned with the victims’ need (say, if other companies would have competencies that put them in a better place to provide help), there may still be a duty to provide help, but this duty may no longer be nondiscretionary. If you relax these conditions even more, the rescue may not even be deemed obligatory. Arguably, a manager is not morally required to devote most of the company’s resources to address a minor need in the community if doing so would risk the long-term survival of the firm. In this case, addressing this need would be considered, at best, supererogatory. There is, of course, “considerable controversy. . . about where obligation ends and supererogation begins on the continuum” (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp and Zalta2019) and about where to draw the line that separates a discretionary from a nondiscretionary duty of rescue. The important point in this article is not to delineate where to draw such a line but to point out that there are duties of rescue that are discretionary and others that are not and that whether a duty of rescue is or is not discretionary will depend on a number of factors, such as the sacrifice required, the risks and costs involved, and the capabilities and position of the company to provide the requisite aid.

To show that managers should be required to fulfill discretionary duties of rescue on behalf of shareholders, we can replicate the structure of the argument provided in the previous section. To do so, we have to show that the duty binds shareholders in virtue of the fact that they have investments in the company and that shareholders who abide by morality would want the manager to discharge this duty on their behalf.

The first condition is easy to establish since the obligation to provide aid emerges from the company’s specific competencies. Shareholders have the ability to remedy, through the company in which they have invested, a bad situation where humans are suffering. If the sacrifices required and potential risks incurred are moderate, and the social need addressed is significant enough, addressing this need falls under the duty of beneficence.

Because the duty to provide aid is narrow and arises from the competencies of the company, shareholders would not, in general, be able to fulfill this duty on their own and can only fulfill it through their company, via the manager.Footnote 15 This entails that (moral) shareholders would recognize that their only way to fulfill this duty is through the company in which they have invested. Thus they would want the manager to fulfill this duty on their behalf. However, because we are assuming that this duty affords discretion concerning whether or not to fulfill it, the duty that the manager is supposed to discharge is a discretionary duty.Footnote 16 I will discuss in section 5.4 how the manager could confront the difficult practical problem concerning how to deal with such discretion. However, before doing this, I will discuss a structurally different duty of beneficence that is narrow and discretionary.

5.2 Narrow Discretionary Duties to Business Partners

Scholars who favor shareholder primacy often argue that beneficence is out of place in market interactions (Friedman Reference Friedman1970; Heath Reference Heath2014a; McMahon Reference McMahon1981). It has been suggested that market interactions are “competitively structured and, therefore, require an adversarial orientation on the part of actors” (Heath Reference Heath2014b, 174). These adversarial relations are not limited to competitors but also include suppliers, financiers, and consumers. Fostering these adversarial relationships is meant to promote a more efficient allocation of resources and products. It is important to note, however, that appeals to the “implicit morality of the market” that rely on the first theorem of welfare economics assume that all the market agents are replaceable and anonymous. As McMahon (Reference McMahon1981, 269) notes, “the proper names of consumers and firms (and the products of firms) must play no role in decisions to buy or sell. Consumers must purchase a given product from whichever producer offers it at the lowest price, and producers must sell to the highest bidder.” In this spirit, Donaldson (Reference Donaldson1992, 277) notes that, whereas in intimate communities, benevolence and solidarity tend to play an important role, in business contexts, these virtues are much less important.

To think, however, that they play no role whatsoever would be to take things too far. As Heath (Reference Heath2007, 368) has remarked, “there are significant cooperative elements in market transactions, especially in cases where long-term contracts are in place.” Not all business transactions take place between anonymous strangers. We build relationships with our business partners. And as these relationships strengthen, they lose their adversarial edge, and there is a moral pressure for us to care for our business partners for their own sake. When a loyal employee is getting married, he may ask the manager for a cash advance to help him fund the wedding party. When the warehouse of a trusted supplier gets flooded, he may request a few days to fulfill his order. Complying with these requests need not be guided by strategic reasons; rather, it is guided by beneficence, by a genuine desire to promote the good of those with whom we interact. It seems callous not to care at all for our long-term business partners, to be indifferent to their plights, in the name of market efficiency.

Like with discretionary duties of rescue, discretionary duties of beneficence to associates 1) bind shareholders qua shareholders and 2) carry over to managers. Moral shareholders would recognize, as principals/beneficiaries of the company that has established these relationships with these business partners, that they are bound by these duties. Shareholders would also recognize that they should not aim to fulfill these duties independently because it is either not feasible or not practical for shareholders to do so. It would not be feasible for shareholders to fulfill some of these duties on their own because the beneficent action may require the use of corporate resources. For instance, only the manager can reorganize the production process to produce other products while the supplier cleans up his warehouse. It would not be practicable for shareholders to fulfill these duties individually, even when shareholders could theoretically fulfill this duty on their own. The transaction costs, logistical difficulties, and overall inconvenience of fulfilling the duty individually speak against doing so. In the foregoing examples, shareholders could, theoretically, pool money to provide the cash advance to the employee (cf. Benabou and Tirole Reference Benabou and Tirole2010, 10). But, as we mentioned earlier, proceeding in this fashion undermines one of the main motivations to “separate ownership and control” at the heart of the principal–agent relationship. Shareholders pool together their resources to, on one hand, reduce the transaction costs that shareholders would incur if they did not have a centralized manager making decisions about the administration of the company on their behalf and, on the other hand, be able to partake of a business venture despite lacking the time, willingness, or competency to play an active role in its administration.

Two caveats are in place. First, saying that in business contexts some adversarial relationships lose their edge need not entail that they lose their adversarial nature altogether. It is open to those who ground the moral legitimacy of markets on considerations about efficiency to insist that market exchanges should generally be conducted in an adversarial fashion where products and services are bought and sold because of their price and quality, not by how long the company has done business with them. From this perspective, if you have a long-term relationship with your provider and another provider offers lower prices and better quality, you ought to switch to the new one. My point is that, within this adversarial environment, beneficence makes demands of us, even if such demands are significantly more limited in their application and demandingness than in our interactions with friends or neighbors.

Second, what grounds these obligations of beneficence toward our business associates are structural features of the situation that have to do with the roles played by the business actors involved. The manager is required to be beneficent to the loyal employee or long-term supplier not because of her personal feelings for the employee or supplier; the obligation arises from her role as a manager, a role that brings with it a (discretionary) moral duty to be beneficent with this employee and supplier, given their loyalty working at or with the company. This discretionary duty of beneficence would bind the manager even if it were her first day on the job and if she lacked any emotional connection to this employee or supplier.

5.3 Taking Stock of Narrow Duties of Beneficence

Allow me to take stock and 1) elaborate on the relationship between the two discretionary duties of beneficence I have discussed in this section and 2) explain in a more general way why narrow duties of beneficence carry over from shareholders to managers. Duties of rescue are narrow because of a specific need that the rescuing party has the capacity to address. The duty of beneficence to business partners is narrow because it is prompted by specific social relationships in the company’s network (even if the company may not be particularly well suited to address the beneficiary’s needs). While both of these are narrow duties of beneficence, what makes each of them narrow is structurally different. In the first case, what is narrow is the type of aid required, in the second, the beneficiary.

While both these duties are narrow in very different ways, it is the fact that they are narrow that ultimately explains why they carry over from shareholders to the manager. Narrow duties carry over from shareholders to managers either because it is not possible for shareholders to fulfill such duties on their own or because, being narrow, they require shareholders to coordinate their efforts to fulfill them. Such efforts would be costly and/or impractical, undermining the separation between ownership and control that is at the heart of shareholder primacy and to which shareholders committed themselves when they bought their shares.Footnote 17

5.4 How to Fulfill Discretionary Narrow Duties of Beneficence

When I discussed the duty of charity, I highlighted that the subjective discretion that it affords allows each person to fulfill it according to the person’s inclinations and personal circumstances. I argued that one of the main reasons why shareholders should be allowed to do charity on their own is that it allows them to do so according to their particular subjective inclinations. However, in this section, I have argued that some duties that afford discretion, narrow duties of beneficence, should be fulfilled by the manager. This poses a difficult practical problem: how to fulfill them in a way that reflects the subjective inclinations and personal circumstances of each shareholder. In what follows, I mention three potential strategies to do so, together with their strengths and weaknesses.

Before doing so, however, it is important to emphasize that when a company has a diverse pool of shareholders, one can be almost certain that no strategy will properly reflect the subjective inclinations and personal circumstances of each and every one of them. Although the manager should try her best to fulfill narrow discretionary duties in ways that address the subjective inclinations of all shareholders, this will not always be possible. This result is perhaps less problematic than one may at first think, given that, by buying shares in a company, a shareholder buys in to a collective project where he puts the interests of the joint venture over his own. This includes corporate decisions concerning beneficence that may not fully conform with his particular interests (cf. Elhauge Reference Elhauge2005, 739).

5.4.1 Getting Input from Shareholders

The first and most obvious proposal would be for managers to get input from shareholders about how they would like their discretionary duties to be fulfilled (cf. Hart and Zingales Reference Hart and Zingales2017a, Reference Hart and Zingales2017b). The idea, of course, is not that shareholders would be consulted for each and every decision (this would, again, undermine the motivation to separate ownership and control by imposing high transaction costs on shareholders). The idea is, instead, to have a set of formal policies and guidelines, approved by shareholders, that would guide the manager’s beneficent decisions (Hart and Zingales Reference Hart and Zingales2017a; Mansell Reference Mansell2013).

While this proposal has much to recommend, in many cases, it will not work. First, there are cases where shareholders may fail to find policies on which they agree. Shareholders of publicly traded companies come from very different backgrounds, have different sensibilities, and are faced with widely varying personal circumstances. This diversity may interfere with their ability to agree on a similar set of policies (Brophy Reference Brophy2015, 782n4). Second, this strategy would require the active participation of shareholders in voicing their views about the direction the company should take in this regard. Given the many financial instruments and institutions separating the ultimate shareholders from the companies in which they invest, and given the extremely high diversification of their holdings, it seems implausible to expect shareholders to have this degree of involvement.Footnote 18 Finally, even if shareholders may agree on a general set of policies, these policies will often lack, because of their generality, sufficient specificity to provide adequate guidance to the manager in many specific cases.

5.4.2 Using Moral Imagination

It has been suggested that when the manager is unable to get reliable information about shareholders’ interests and circumstances, she should attempt to use her moral imagination to predict how they would want her to fulfill discretionary duties on their behalf (Brophy Reference Brophy2015). Without denying that it is valuable for managers to use their imaginative power to enlarge the perspectives from within which they make corporate decisions, it is important to acknowledge the limits on this proposal. Because our power of moral imagination is limited, a manager will often end up imagining shareholders in her own likeness (Anderson Reference Anderson2015). If she does so, this strategy will lead the manager to pursue corporate beneficent initiatives that reflect her personal preferences and not shareholders’ (Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006; Minow Reference Minow1999, 202).

5.4.3 Seek Strategic Alignment

The third proposal I want to mention starts from the recognition of the one thing on which nearly all (moral) shareholders typically coincide: wanting to get a financial return on their investment. The fact that this is a self-interested goal may lead one to think that it should play no role in how a duty ought to be discharged. This conclusion is mistaken in the case of discretionary duties of beneficence. As I discussed, discretionary duties allow the agent to appeal to his inclinations, passions, and sensibility to decide whether to fulfill them. The fact that all shareholders agree on the economic mission of the company suggests that they would all support corporate beneficence that supports such a mission. This fact can provide valuable guidance to the manager. In particular, it entails that part of what could be factored in to a managerial decision concerning when and how to fulfill discretionary duties of beneficence is an assessment of the extent to which fulfilling the duty aligns with the strategic goals of the company. By reflecting on these goals, managers would be better able to respond to the various and disparate demands of beneficence by ranking which of these demands should be given priority.

It is important to avoid a potential misunderstanding with this third proposal. I am not suggesting that beneficence should only be pursued when it serves the financial interests of the firm or that strategic decisions should be the single metric to make decisions about how, when, and whom to help. The duty of beneficence, after all, is structured by an inherent tension between the needs of the party that is being helped and the sacrifices imposed on the helping party. If the needs are grave enough, the manager’s obligation to fulfill such needs may override her aspirations to align corporate beneficence with the company’s strategic financial goals. What I am suggesting is that decisions about which discretionary duties of beneficence to fulfill should include considerations about the strategic financial advantages for the firm. Provided that the ultimate goal of the beneficent actions is to promote the good of others, the fact that this also benefits the firm financially does not entail that the manager is not, ultimately, fulfilling these duties (Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006, 200).

5.5 Merck and River Blindness

I’d like to conclude this section by applying the framework I have developed to a business case that has played a central role in the scholarly discussion in business ethics and is frequently discussed in business ethic classes: Merck’s donation of Mectizan to cure river blindness.Footnote 19

When Merck started doing research into a potential drug to combat river blindness, eighty-five million people in Africa, the Middle East, and South America were at risk. Some small towns within these regions were so severely affected that almost all their residents were infected and all adults older than forty-five years were blind.Footnote 20 Merck’s research into river blindness originated from the suspicion that ivermectin, one of Merck’s best-selling veterinary drugs at the time, could be used to address river blindness in humans. Merck’s executives knew that marketing this potential drug would not be straightforward because those afflicted by river blindness had a very limited ability to pay for the treatment. Despite this, Dr. Roy Vagelos, then head of Merck’s research labs, approved research funding into it. He recognized that failing to pursue this line of research could demoralize Merck’s scientists, many of whom had been recruited on the promise that they would be contributing to alleviating human suffering. Also, the project would enhance Merck’s knowledge of parasitology, one of Merck’s core strengths. Vagelos was hopeful that, if Merck developed a successful drug, the company would find a way to recoup the investment.

Research led to the development and successful approval of Mectizan, a powerful drug to cure river blindness. Even though the drug was cheap and relatively easy to administer, Merck’s executives were unsuccessful in finding government or nongovernmental agencies willing to buy and distribute the drug. After some deliberation, Merck’s executives decided to donate the drug under the now famous slogan “as much as needed for as long as needed.”

Close parallels between Merck’s case and Earthquake may tempt one to think that Merck was bound by a perfect duty of rescue to donate Mectizan. This conclusion, however, would be too quick; the two cases also have important dissimilarities. In what follows, I argue that, if one thinks that being uniquely placed is a necessary condition for a duty to be nondiscretionary, then Merck was under a nondiscretionary duty to address the epidemic, but only under a discretionary duty to produce and distribute the drug.Footnote 21

A significant difference between Merck’s donation of Mectizan and Earthquake is that Merck was not uniquely placed to produce and distribute the drug. This might, at first, sound surprising, given that Merck was the only company that had property rights on the drug. But having the property right to a drug and having the competency and know-how to produce it need to be distinguished here.Footnote 22 Even if Merck had exclusive property rights over Mectizan, it was not the only company that could produce and distribute the drug. Merck could have given up its property rights over the patent or simply allowed other pharmaceutical organizations to legally produce and distribute the drug.

However, even if Merck had a discretionary duty to donate Mectizan, the company was nevertheless bound by a nondiscretionary duty to address the epidemic. If Merck felt too burdened by the risks and long-term commitments involved in donating Mectizan, or if its executives thought that shareholders wanted to pass on the opportunity to help, Merck still had a perfect obligation to address the epidemic by giving up the property rights over the patent of Mectizan or, at the very least, by allowing other companies, governments, or NGOs that were willing to donate the drug to do so. The duty to do this is not discretionary because it meets all the four necessary conditions I laid out in section 4: the company was able and uniquely placed to provide help, the cost and risks of doing so were minimal, and grave consequences would follow from not doing so.

According to Bollier, Weiss, and Hanson (Reference Bollier, Weiss and Hanson1991, case C, 1), the World Health Organization would have likely bought the drug from Merck for a few cents. While this price was much lower than the official price of three dollars, it would still have allowed Merck to recoup some of the costs of the donation. Merck, however, decided instead to lead the effort directly, not only to produce and donate the drug (something on which it had expertise) but also to distribute it (something on which it did not have expertise). It is instructive to discuss some of the reasons and considerations that may have led Merck to fulfill its discretionary duty to produce and distribute Mectizan. These allow us to see the interesting ways in which altruism and self-interest can be at play in discharging this duty.

According to Bollier, Weiss, and Hanson (Reference Bollier, Weiss and Hanson1991, case C, 1), part of what led Merck to produce and distribute the drug had to do with beneficence: “Merck felt that this was the best way to get the drug to as many people as quickly as possible.” But Merck also had prudential concerns for proceeding as it did. Being directly involved in producing and distributing the drug was going to generate significant goodwill from third world nations, the World Health Organization, and the company’s own employees, who were proud of Merck’s decision (Bollier, Weiss, and Hanson Reference Bollier, Weiss and Hanson1991, case B, 4).

Merck had the expertise to manufacture the drug but not to distribute it. Despite this, Merck decided to coordinate the effort to distribute the drug. To do so, the company created the Mectizan Expert Committee, a panel of seven international experts that “established guidelines and procedures for public health programs that wished to distribute Mectizan” (Bollier, Weiss and Hanson Reference Bollier, Weiss and Hanson1991, case D, 1). This was a clever solution to address many of the risks associated with the donation. The panel, funded by Merck, allowed the company to keep control of how the drug was distributed, in particular, to ensure that the drug was promptly and adequately distributed, that adverse reactions were tracked, and that the drug was neither misused nor transacted in black markets that could cannibalize into the market for ivermectin. Because the panel was an external body, independent from Merck, it served to insulate Merck from criticisms from the decisions about who could or could not distribute the drug. Finally, by allowing organizations approved by the committee to distribute the drug, Merck avoided creating “a dependency that would place more demands on the company or restrict its options in the future” (Bollier, Weiss, and Hanson Reference Bollier, Weiss and Hanson1991, case C, 4).

6. CONCLUSION

Business ethics scholars, worried about the inordinate centrality that profits and stock prices play in corporate managerial decisions, and guided by the intuition that “corporations have a responsibility to alleviate human misery” (Hsieh Reference Hsieh2009a), have gone to great lengths to offer grounds to justify the moral duty of managers to engage in corporate beneficence. Because it has been assumed that shareholder primacy does not have the resources to ground such a duty, a wide variety of scholars in the field have proposed and defended alternative models of corporate governance (Bower and Paine Reference Bower and Paine2017; Ciepley Reference Ciepley2013; Evan and Freeman Reference Evan, Freeman, Beauchamp and Bowie1993; Freeman Reference Freeman2007; Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and Colle2010; Ghoshal Reference Ghoshal2005; Ireland Reference Ireland1999; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Stout Reference Stout2012). Other scholars have worked within the paradigm of shareholder primacy, but have tried to justify the corporate duty of beneficence by appealing to contentious notions of corporate agency or personhood (Hsieh Reference Hsieh, Orts and Smith2017a; Smith Reference Smith, Arnold and Harris2012); by showing that situations of extreme social need may justify breaking the fiduciary duties to shareholders (Dunfee Reference Dunfee2006); or by arguing that the fiduciary duties of managers are limited to making financial returns on shareholders’ investments and that, beyond a reasonable return, the manager has discretion to use the company’s proceeds for beneficent deeds (Lee Reference Lee2020; Ohreen and Petry Reference Ohreen and Petry2012; Strudler Reference Strudler2017).

Among the main contributions of this article has been to show that one need not go beyond the paradigm of shareholder primacy to ground a good deal of the duties of beneficence that scholars in the field expect managers to fulfill in their corporate roles. Moreover, the manager’s obligation to fulfill these duties is not in tension with her obligations to shareholders; it arises from the fact that she is acting on their behalf.

By showing that some duties of beneficence are wide and others are narrow, and that some offer discretion and others do not, I have provided a more granular look into the duty of beneficence. These distinctions allow one to see more clearly that, if a manager acts on behalf of shareholders, some of these duties will bind her, and others will not. Among those that do, some will allow for more discretion than others.

This approach may provide a blueprint to generalize the account offered to other types of imperfect duties. In addition, because most of the arguments I provided relied only on the relationship between agents (or trustees) and principals (or beneficiaries), they can be seen to provide a blueprint with which to analyze the duties that bind managers who act on behalf of a wider set of stakeholders beyond just shareholders.

Acknowledgements

Research on this article was partly funded by a Fordham University Faculty Research Grant. Hannah Daru contributed to this article with invaluable editorial support. Akash Jethwani and Ying Yang provided helpful research assistance. I express my gratitude to the audiences at the workshops where I presented this article: the Business Ethics in the 6ix conference, Georgetown’s GISME workshop, the Hoffman Center for Business Ethics Brown Bag Series, and the Zicklin Center Normative Business Ethics Workshop. I also thank for their conversations, ideas, and feedback Aaron Ancell, Brian Berkey, Matthew Brophy, Gaston de los Reyes, John Hasnas, Joseph Heath, Peter Jaworski, Samuel Mansell, Jeff Moriarty, Luke Semrau, David Silver, and Hasko von Kriegstein. All opinions expressed in this article are my own, and all errors should be attributed to me.

Santiago Mejia is an assistant professor of business ethics at the Gabelli School of Business, Fordham University. His research interests span moral psychology, normative ethical theories of businesses, organizational behavior, and virtue ethics. He is developing a project showing that certain forms of shareholder theory are ethically defensible. He is also doing research on the nature of character and ethical development, attempting to bring together empirical results from organizational behavior, social psychology, cognitive science, and clinical psychology with theoretical insights in virtue ethics. Finally, he is currently exploring what the Socrates of the early Platonic dialogues may have to contribute to business scholarship.