Archaeology, and specifically excavation, is a destructive endeavour. Often, ‘to understand something, we have to destroy that very thing in the process’ (Lucas Reference Lucas2001, 35). Yet archaeology is simultaneously constructive. Archaeologists use material remains, notes, drawings and photographs to interpret and produce narratives about the past. Photography has been a particularly important though often under-theorized aspect of archaeological research. Although seemingly simple representations, photographs are paradoxical. They are simultaneously objective and subjective, truthful and creative. Rather than simply recording the past, photographs help construct it.

This article considers the contradictory nature of photography generally and the specific relationship between photography and archaeology. It then looks at the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico and examines how various individuals and projects have photographed ancient Maya sites, architecture and artifacts. In the mid nineteenth century, explorers recorded photographs to support diffusionist theories of Maya origins. In the mid twentieth century, professional archaeologists recorded photographs to document the Maya past—and the practice of archaeology—faithfully, neutrally, and scientifically. And, over the last two decades, researchers have used photography for additional purposes, including to share power more equitably with members of local communities and to make archaeology a more inclusive and more relevant endeavour.

Indeed, several have demonstrated that photography is a useful tool for engaged archaeology—archaeology that is ‘community-serving rather than strictly research-generating’ (Chesson et al. Reference Chesson, Ullah and Iiriti2019, 422). This article argues that the reverse is also true: insights from engaged archaeology are useful tools for archaeological photography generally. By making photographic choices explicit and asking, ‘photography for whom?’ and by including people and other aspects of the contemporary world in their photographs, scholars can emphasize that archaeology is a decisively human and necessarily political endeavour, and that archaeological sites and artifacts are dynamic and efficacious parts of the contemporary world. The article concludes by looking beyond engaged archaeology to suggest that scholars can also use photography to represent the past dialectically, and thereby avoid problematic linear notions of progress and decline (Benjamin Reference Benjamin and Redmond1974; 1999; Lucas Reference Lucas2005; Olivier Reference Olivier2004).

Taking photographs

Be they of people, places, or things, photographs are ubiquitous. Indeed, ‘photography has become so common to our world that we hardly see it’ (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 15). Perhaps because of their prevalence, photographs are often taken for granted or assumed to be self-evident forms of representation. Yet they are profoundly complicated and, in many ways, contradictory. Photographs are simultaneously objective and subjective. Unlike other types of images, photographs capture physical traces of their subjects. As Susan Sontag (Reference Sontag1973, 154) notes in her famous rumination On Photography, ‘a photograph is never less than the registering of an emanation (light waves reflected by objects)—a material vestige of its subject’. Photographs are compelling, in part, because they are tangibly linked to their subjects. Unlike a painting or drawing, a photograph is a physical manifestation of its subject, a ‘trace, something stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask’ (Sontag Reference Sontag1973, 154).

Nevertheless, photographs are undoubtedly subjective and selective interpretations of the world (e.g. Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Papadopoulos, Stewart and Szegedy-Maszak2005; Parno Reference Parno2010; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2006). The photographer must decide what to photograph and what to ignore, what should be in the frame and what should remain beyond it. The photographer must also decide how to photograph. She or he must make conscious choices about lighting, angles and staging, among other factors. Further, a photographer must necessarily represent her or his subject out of context, unmoored from its surroundings. A photograph is selective, in part, because it is a spatial and temporal fragment that ‘accomplishes its representation only by isolating one portion from the otherwise organic and continuous visual world’ (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 119).

Photographs are contradictory in other ways. They, for instance, simultaneously make significant and devalue their subjects. The mere act of photographing suggests that a subject is of consequence and worth recording. As Sontag (Reference Sontag1973, 28) writes, ‘to photograph is to confer importance’. Yet photography also makes the unique reproducible (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 119) and the inaccessible consumable (Sontag Reference Sontag1973, 68). In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin (Reference Benjamin1936) considers how photography transforms a unique moment in space and time into an object that can be replicated and possessed. By ‘making many reproductions it [photography] substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence’ (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1936, pt. II). Such reproductions—and their distribution throughout the world—interfere with the subject's aura, ‘its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be’ (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1936, pt. II). The result, for Benjamin and others, is that the subject depreciates in value (Benjamin Reference Benjamin1936, pt. II; but see Berger Reference Berger1972).

Further, photographs are at once stable and ever changing. The images themselves remain constant, capturing and preserving past moments for eternity. Yet the meanings of those images change dramatically over time, with different viewers and in different contexts (e.g. Guha Reference Guha2013; Parno Reference Parno2010; Sontag Reference Sontag1973,105–7). This ambiguity of meaning suggests another reason why photographs are so potent. Indeed, ‘it is their muteness that reinforces their seductiveness’ (Parno Reference Parno2010, 118), their indeterminacy that leaves them open to interpretation (Sontag Reference Sontag1973, 23). This lack of inherent meaning is particularly evident when the same photograph acquires multiple captions over its lifetime.

Archaeological photography

Despite—or perhaps because of—its many contradictions, photography has been an integral aspect of archaeology since the inception of the discipline (e.g. Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011; Hall Reference Hall2017; Hamilakis et al. Reference Hamilakis, Anagnostopoulos and Ifantidis2009; Shanks & Svabo Reference Shanks, Svabo and Gonzales-Rubal2013). Temporally, photography and archaeology developed together. But they are also intertwined in more deep-seated ways. As others have noted, photography and archaeology ‘share a common structure’ (Shanks & Svabo Reference Shanks, Svabo and Gonzales-Rubal2013, 90) and partake ‘of the same ontological and epistemological principles’ (Hamilakis et al. Reference Hamilakis, Anagnostopoulos and Ifantidis2009, 285). Both photography and archaeology make sense of the world through fragments—be they pottery sherds or images. And both are attempts to document and preserve the past, to make what is now absent present again. Indeed, ‘archaeological photography pairs the technology of picturing absence with the science of deciphering absence’ (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 8).

At least historically, photographs have had two primary functions in archaeology. First, they have served as documentation of sites, features and artifacts (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 141; Guha Reference Guha2013; Parno Reference Parno2010; Pétursdóttir & Olsen Reference Pétursdóttir and Olsen2014, 11). Put differently, archaeologists have often understood photographs as raw data to be analysed and do ‘not look at the photograph so much as to look through it to the object pictured’ (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 26, italics original; see also Scorer Reference Scorer2017, 145). Second, archaeologists have used photographs to generate interest in, and support of, archaeology and to communicate their findings with non-specialists. Put simply, photography has been an integral aspect of archaeological public engagement.

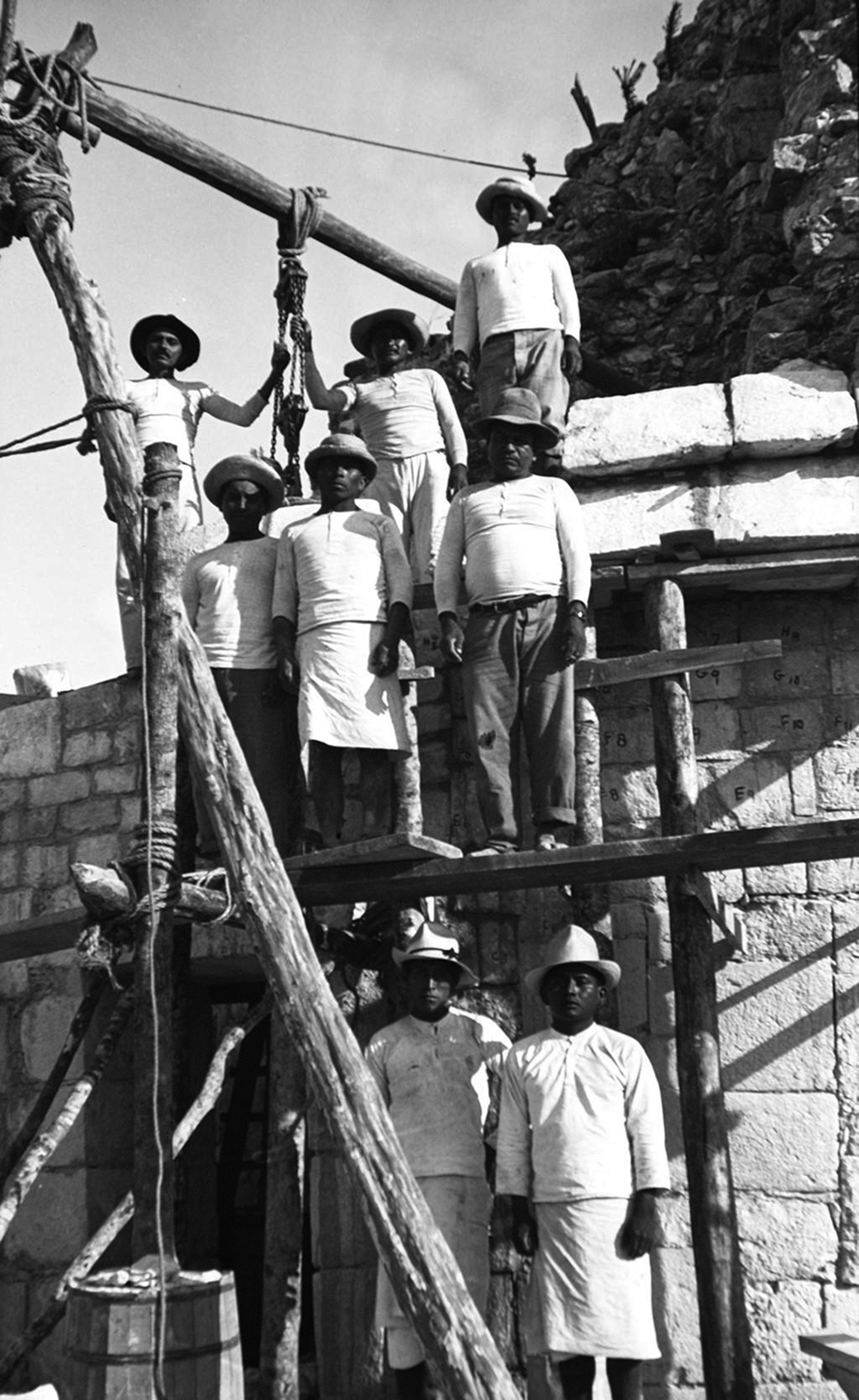

Whether photographing for colleagues or non-specialists, archaeologists generally follow a set of conventions first established in the beginning of the twentieth century (e.g. Petrie Reference Petrie1904, 73–84). These conventions are often implicit rather than explicit and frequently taken for granted rather than critically analysed. Notably, archaeological photographs tend to focus on objects and exclude contemporary people and their traces (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 81; Pétursdóttir & Olsen Reference Pétursdóttir and Olsen2014, 13). Nevertheless, there does exist a body of historical photographs from around the world that depict Indigenous workers. These workers are often recorded massed together in a large group, ‘testifying not only to the scale of organized archaeology, but also to the lack of individual identity attributed to workers’ (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 73). When photographed individually, Indigenous workers are often shown as human scales and arrows indicating the size and location of archaeological objects (Castañeda Reference Castañeda2000, 51; but see Riggs Reference Riggs2017). In their well-known analysis of archaeological photographs published in National Geographic, Joan Gero and Dolores Root (Reference Gero, Root, Gathercole and Lowenthal1990, 30) note that Indigenous peoples are frequently ‘posed either standing or striding in front of ruins, human scales for more than the size of archaeological features—scales, too, for the differences in the human condition’.

Also notable is the convention of extensively preparing and staging artifacts and excavation units prior to photographing them (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 81–4; Parno Reference Parno2010; Pétursdóttir & Olsen Reference Pétursdóttir and Olsen2014). Footprints are brushed away, leaves are removed and buckets, trowels and other tools are placed out of sight. In 1904, W.M. Flinders Petrie (Reference Petrie1904, 76) wrote that ‘the preparation of the object is a very important point’ of archaeological photography and advised archaeologists to dust reliefs with sand to smooth them, pack the ground between artifacts with dark dirt to improve contrast and fill inscriptions with white powder to make them more legible. As Þóra Pétursdóttir and Bjørnar Olsen (2014, 13) write,

the very peculiar aesthetics of site-styling long institutionalized in archaeology … the imperative of cleaning surfaces, removing disturbing debris and modern traces, and thus temporarily dressing sites in a neat and tidy way can hardly be described as representative for how the site ever has been (either during fieldwork or in the past).

Consequently, archaeological photographs often record not how a site actually looks, but how its excavators would like it to be (Bohrer Reference Bohrer2011, 84). Rather than documenting a site, artifact, or feature as it appears, such photographs instead create something new (Hall Reference Hall2017). Even attempts at unbiased representations ‘overlook the actual archaeology in the pursuit of some elusive objectivity’ (Parno Reference Parno2010, 124).

If photography has helped construct rather than merely document the archaeological record, how have photographs impacted our understanding of past peoples? More specifically, how have archaeologists photographed ancient Maya sites, architecture and artifacts, and how have such images influenced our understanding of the Maya past and present?

Photography and Maya archaeology

The ancient Maya were a diverse group of people who spoke Mayan languages and who lived in the area occupied by contemporary Guatemala, Belize, portions of Mexico including the Yucatan peninsula, and the western areas of Honduras and El Salvador, between approximately 1000 bce and 1500 ce.Footnote 1 Foreign groups have studied ancient Maya peoples from the time of contact until the present, and the ‘Maya past has proven to be a bottomless horn of plenty—a boundless source of inspiration, ideas, and iconography’ (Lerner Reference Lerner2011, 5).

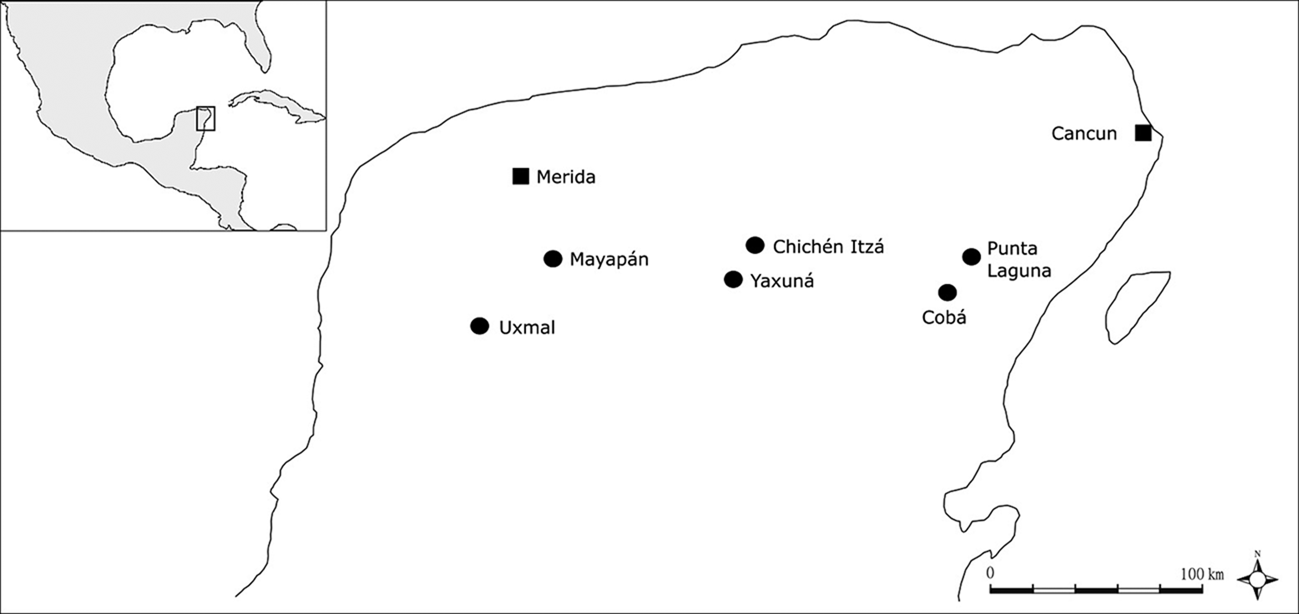

The history of Maya studies can usefully be divided into three broad periods: the time of explorers and adventurers (1821–1913); the institutional period (1914–1957); and an era of more recent research (1958–2000).Footnote 2 To understand how ancient Maya places and objects have been photographed, this article examines photographs taken by two different individuals or projects during each of these three time periods, before reviewing current trends. To facilitate the analysis, the article limits itself to one geographic area—the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico (Fig. 1). Specifically, the article considers photographs taken by Désiré Charnay, Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon, the Carnegie Institution of Washington programme at Chichén Itzá, the Carnegie Institution of Washington programme at Mayapán, the Cobá Archaeological Mapping Project and the Selz Foundation Yaxuná Project.

Figure 1. Map of the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, showing the location of all sites mentioned in the text. Archaeological sites are marked by circles and contemporary cities are marked by squares.

Explorers and adventurers: 1821–1913

After Mexico declared its independence from Spain in 1821, foreign explorers and adventurers began travelling throughout the Maya area and documenting sites, structures and monuments then unknown in the United States and Europe. These individuals sought to explain the existence of Maya ruins and ascertain who built them (Evans Reference Evans2004, 2–4, 10–12). The ‘primary question facing nineteenth-century scholars of the Mesoamerican past concerned the monuments’ ethnic and historical authorship’ (Evans Reference Evans2004, 11).

Désiré Charnay

Désiré Charnay, a French explorer working under American patronage, was among the first to photograph archaeological sites in the Yucatan peninsula. Between 1857 and 1860, he travelled throughout Mexico, photographing places such as Mitla and Palenque. While in the Yucatan peninsula, he visited Chichén Itzá and Uxmal and published the resulting photographs as part of his Cités et ruines américaines (Charnay Reference Charnay1863). This volume, with the ‘first widely available photographic images of the ancient Mesoamerican monuments’ (Evans Reference Evans2004, 105), included nine photographs of Chichén Itzá and fifteen of Uxmal.Footnote 3

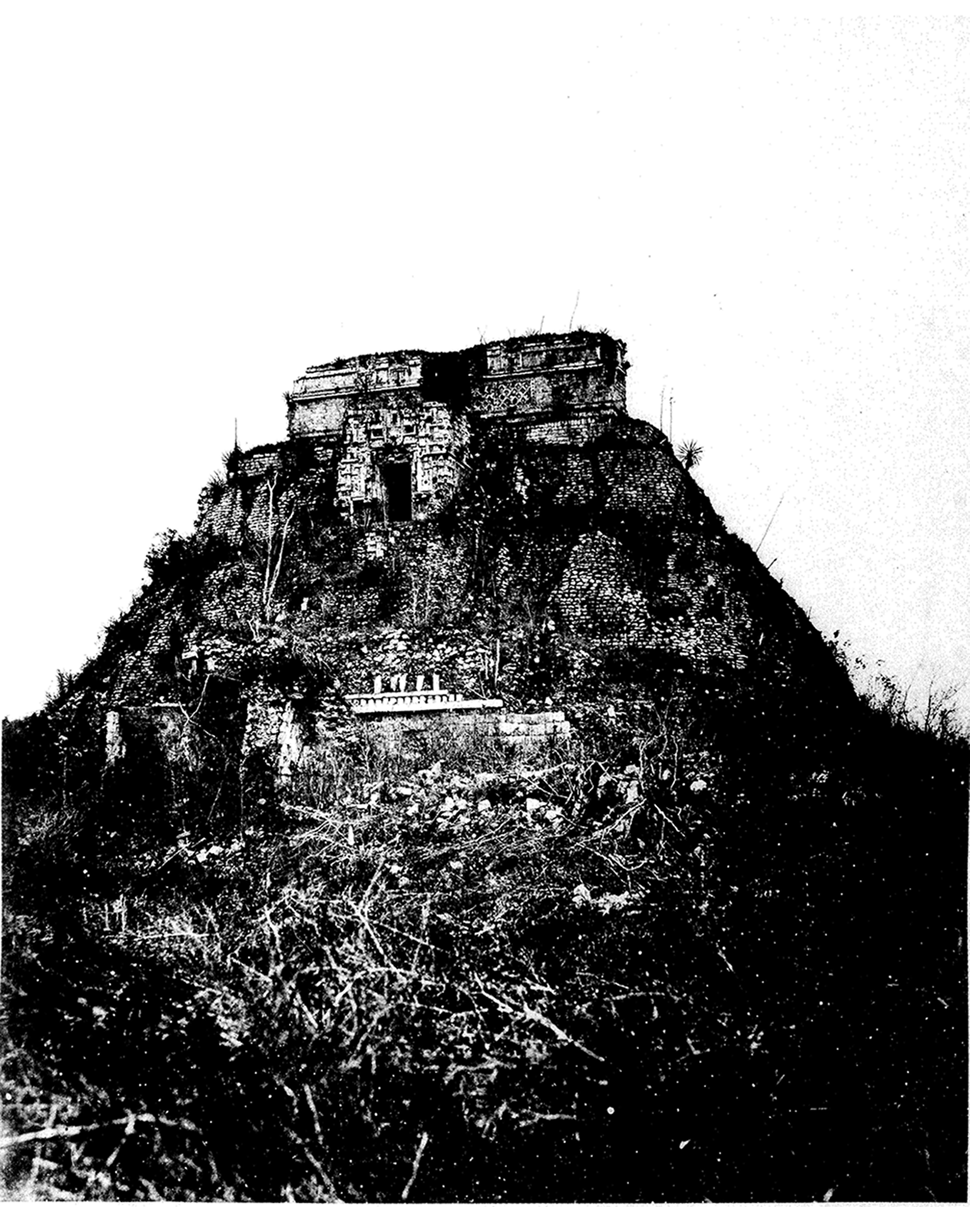

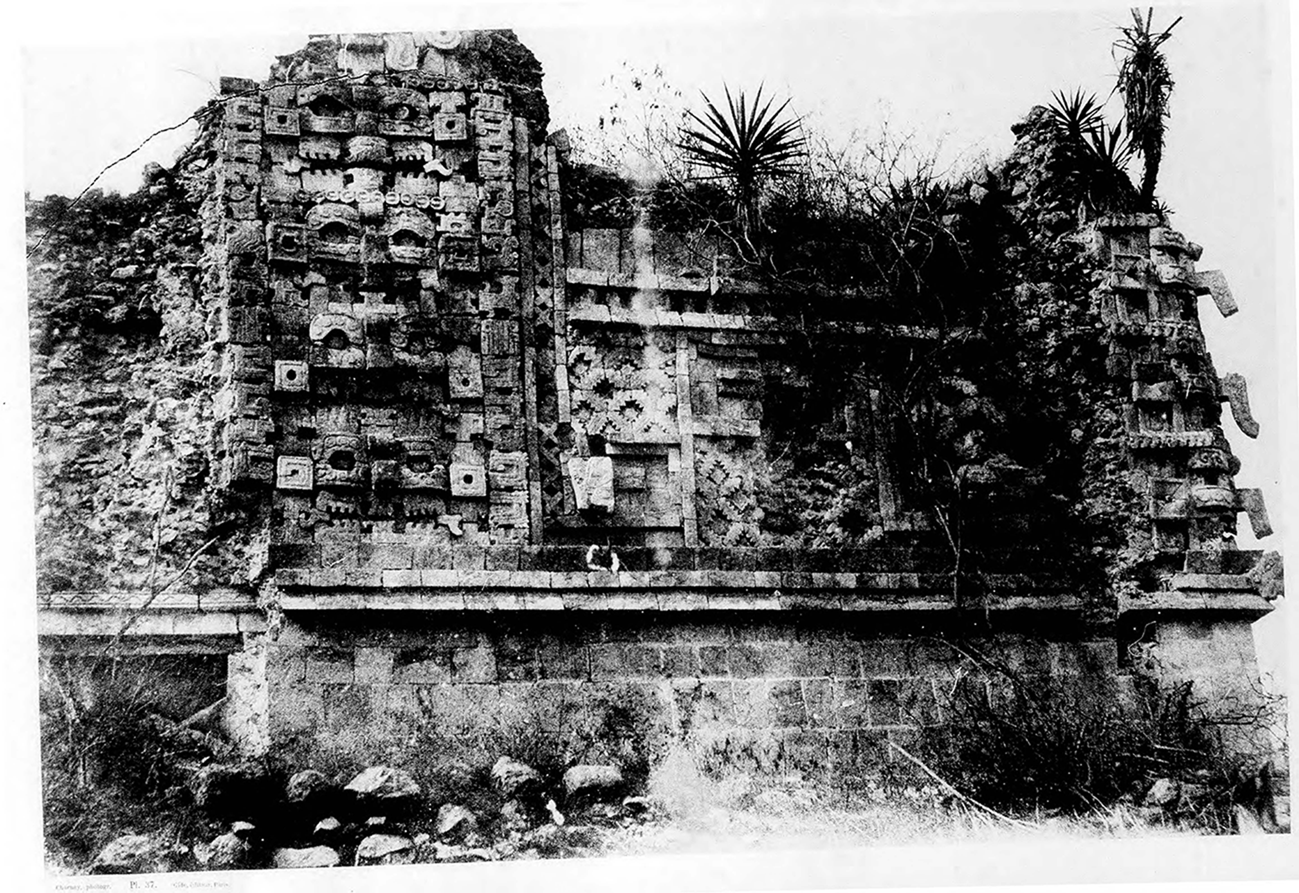

At both sites, Charnay photographed the tallest structure from a distance: the Castillo at Chichén Itzá and the Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmal (Fig. 2). The resulting images suggest the monumentality and inaccessibility of these buildings. Charnay took the other photographs at close range to document architectural and iconographic details, and specifically Puuc mosaics (Fig. 3).Footnote 4 Importantly, not all structures are represented equally in Charnay's photographs. At Uxmal, for example, nine of the 15 photographs are of one building, the Nunnery Quadrangle (Davis Reference Davis1981, 127). Further, only four of the 24 photographs include people. In each of these instances the person is minuscule, posed in the doorway of a structure, and serves only as a scale for the size of the architecture.

Figure 2. Désiré Charnay's photograph of the Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmal. (From Charnay Reference Charnay1863, pl. 35. In the public domain.)

Figure 3. Désiré Charnay's photograph of a Puuc mosaic at Uxmal. (From Charnay Reference Charnay1863, pl. 37. In the public domain.)

Charnay popularized images of ancient Maya architecture and allowed viewers to visit the sites vicariously: ‘For a crucial decade or more, the world came to know these structures through Charnay's eyes’ (Davies Reference Davies2014, 162). Critically, Charnay's photographs ‘conveyed both the mystery of the structures and the romance of adventure’ (Davis Reference Davis1981, 160). The size of the published photographs—71 cm by 54 cm—and their resolute focus on monumental structures and elaborate iconography suggest they were intended to impress rather than merely inform (Aguayo Hernández Reference Aguayo Hernández2020). Further, by selectively emphasizing certain types of structures and certain types of iconography, Charnay portrayed sites throughout Mesoamerica as homogeneous and argued that the Maya and all other Mesoamerican peoples derived from the Toltecs, a group he thought to be ethnically linked to ancestral populations of northern Europe. Put differently, Charnay thought all Mesoamerican achievements could be credited to the Toltecs, who he understood—obviously incorrectly—as the ‘New World Aryan culture bearers’ (Evans Reference Evans2004, 112). He thus used his photographs to support the diffusionist and ethnocentric argument that Maya ruins were ultimately the result of European ingenuity.

Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon

A decade after Charnay published Cités et ruines américaines, Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon travelled to Mexico to explore archaeological sites throughout the Yucatan peninsula. From 1873 to 1884, the married couple visited and documented Chichén Itzá, Uxmal and Mayapán, among other places. They recorded a multitude of photographs, including approximately 500 at Chichén Itzá alone (Desmond & Messenger Reference Desmond and Messenger1988, 30). Unlike Charnay, they also learned to speak Mayan and established a rapport with local Maya peoples (Desmond Reference Desmond1983; Reference Desmond2009; Desmond & Messenger Reference Desmond and Messenger1988). The Le Plongeons’ photographs appeared in several of their own publications, including Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx (A. Le Plongeon Reference Le Plongeon1896), The Monuments of Mayach and their Historical Teachings (A.D. Le Plongeon Reference Le Plongeon1896) and Sacred Mysteries among the Mayas and the Quiches (A. Le Plongeon Reference Le Plongeon1909). Their photographs also appeared in contemporary reports on their explorations (e.g. Salisbury Reference Salisbury1877) and in popular publications such as Harper's Weekly (Evans Reference Evans2004, 129).

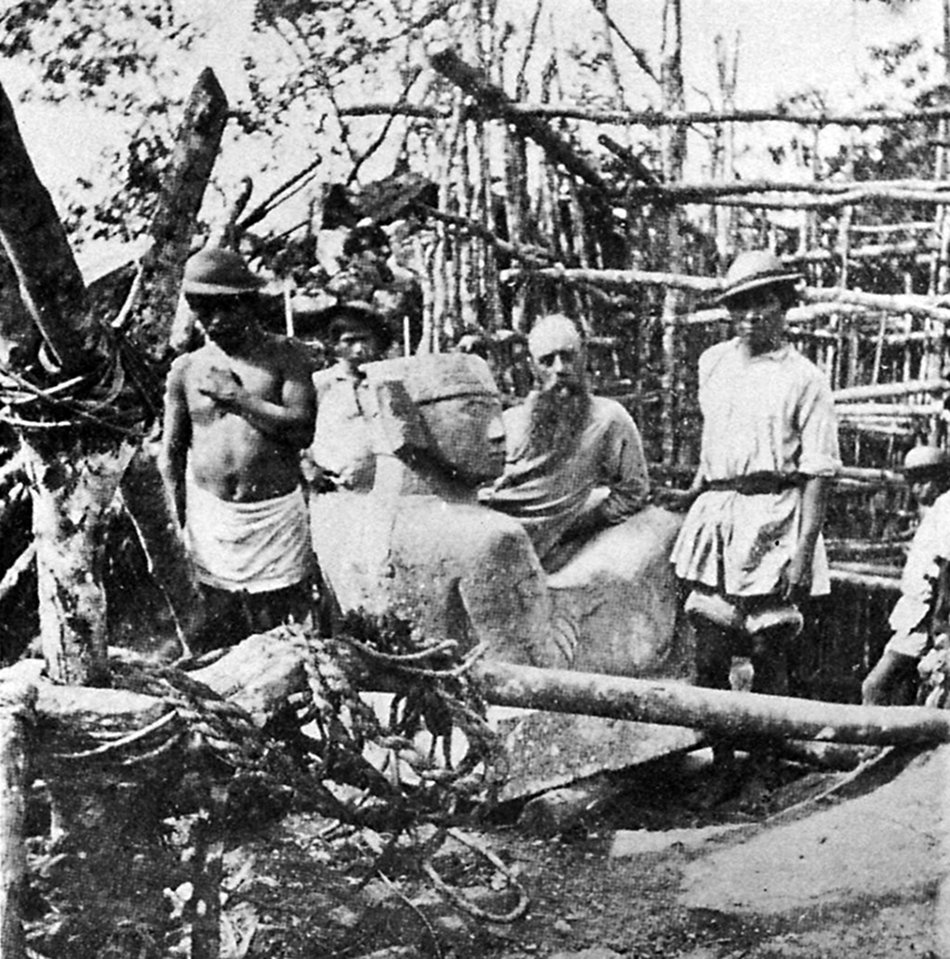

The Le Plongeons recorded images not only of architecture and iconography, but also of artifacts and the practical aspects of their work. For example, they photographed the relocation, after excavation, of a large and heavy Chacmool sculpture and their living conditions in the Governor's Palace at Uxmal (Fig. 4). The Le Plongeons also photographed people, and in roles beyond human scales for architecture. They recorded images of the Maya individuals who assisted them as workers and guards, and they recorded images of themselves. Some of these photographs are organic, including one showing Augustus photographing an architectural frieze from a precarious position atop a ladder. Others were intentionally staged, including one showing Augustus and several unnamed Maya individuals posing by the Chacmool sculpture (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon's living conditions at Uxmal. (From A.D. Le Plongeon Reference Le Plongeon1896, fig. 8. In the public domain.)

Figure 5. Augustus Le Plongeon and Maya individuals posing with a Chacmool sculpture. (From Salisbury Reference Salisbury1877, pl. 9. In the public domain.)

Like Charnay, the Le Plongeons used their photographs to support diffusionist claims. They did not, however, suggest Maya ruins ultimately derived from European ingenuity. Instead, the Le Plongeons argued the reverse, that Maya peoples were ‘world culture bearers, descendants of the Atlanteans, and founders of the Babylonian and Egyptian civilizations’ (Desmond Reference Desmond1983, 2). Absurdly, the Le Plongeons created a narrative of the Maya past based on the actions of Queen Móo and Prince Coh. This invented story ‘tells of the love between Queen Móo and Prince Coh, of Prince Coh's death at the hands of his brother Aac, and of Queen Móo's final escape to Egypt where she is welcomed as Isis’ (Desmond Reference Desmond1983, 167). Even more absurdly, the Le Plongeons suggested that they themselves were Queen Móo and Prince Coh reincarnated (Desmond & Messenger Reference Desmond and Messenger1988, 119). For the Le Plongeons, ‘the remains of ancient Mexico and Central America represented nothing less than the seeds of world civilization … and the former kingdom of their own reincarnated souls’ (Evans Reference Evans2004, 127). It is in part for this reason that they—unlike Charnay—so often photographed themselves with ancient Maya architecture and sculpture: The Le Plongeons literally inserted themselves into Maya history.

The institutional period: 1914–1957

By 1914, explorers and adventures like Charnay and the Le Plongeons had been replaced by professional archaeologists working at the behest of universities, museums and institutes. These organizations funded long-term, large-scale, scientific field projects to collect extensive data about the Maya past (McKillop Reference McKillop2006, 47). The Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW)—a private, non-profit organization dedicated to research—was the most prominent organization working in the Yucatan peninsula during this time (see Weeks Reference Weeks2006a).

The CIW programme at Chichén Itzá

The CIW designated Sylvanus Morley as Research Associate in Middle American Archaeology in 1914 and, in 1924, Morley initiated the Chichén Itzá Project, which ran for 17 years (Weeks Reference Weeks and Weeks2006b, 7–10). From the outset, Morley emphasized that photography would be an integral aspect of the project, writing that ‘no branch of the work except excavation will be of greater importance’ (Morley Reference Morley and Weeks2006, 36). He recommended that project members ‘make a complete photographic record of the site, showing the progress of the excavations … groups of buildings, single buildings, architectural and sculptural details, statuary, hieroglyphic inscriptions, mural paintings, etc.’ (Morley Reference Morley and Weeks2006, 36). Accordingly, project members took thousands of photographs. Some appeared in academic reports (e.g. Morley Reference Morley and Weeks2006) and others in popular publications such as National Geographic Magazine (e.g. Morley Reference Morley1925; Reference Morley1936).Footnote 5

Members of the Chichén Itzá programme sought to document the practice of archaeology and Maya history faithfully, neutrally and scientifically. Yet, despite the seeming completeness of the project's photographic records, certain omissions are conspicuous. For instance, while there exist several hundreds of photographs of excavation and architectural reconstruction, there are few if any photographs of laboratory work. Washing, drying, sorting and analysing artifacts thus remained a mostly invisible part of the archaeological work at Chichén Itzá.

Further, staff members and Maya workers were generally photographed differently. Staff members were more often, though not always, shown at work, excavating, drawing and, in some instances, photographing (Fig. 6). In these images, staff members’ faces are turned away from the camera, suggesting the photograph was intended to capture an activity rather than an individual. Maya workers were more often, though not always, shown posed, standing or sitting near architectural features with their faces towards the camera (Fig. 7). In some cases, the photographer seems intentionally to have stopped work to stage the photograph. Such posing suggests these images were intended to capture individuals rather than an activity, Maya faces rather than archaeological practice. These photographs graphically link the ancient Maya past with the contemporary Maya present. But they also exotify the Maya and suggest that it is they themselves, rather than their actions, that are most worthy of photographing (see also Castañeda Reference Castañeda2000, 51).

Figure 6. Members of the CIW Chichén Itzá staff shown at work, drawing mural paintings. (From Artstor: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Collection: Carnegie Institution of Washington. 58-34-20/31246.)

Figure 7. A posed photograph of Maya individuals working as part of the CIW project at Chichén Itzá. (From Artstor: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Collection: Carnegie Institution of Washington. 58-34-20/31760.)

The CIW programme at Mayapán

In 1949, the CIW initiated its final major project in the Maya area at Mayapán. Directed by Harry Pollock, this project aimed to ‘examine the final expression of pre-Hispanic Maya culture’ (Weeks Reference Weeks and Weeks2006b, 17). Over six years, staff members recorded thousands of photographs. These images appeared primarily in published reports (see Weeks Reference Weeks2006a) including Mayapan, Yucatan, Mexico (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962) and The Pottery of Mayapan (Smith Reference Smith1971), though Tatiana Proskouriakoff (Reference Proskouriakoff1955) included two photographs of effigy censers in an article in the popular publication Scientific American.Footnote 6

The corpus of photographs from Mayapán is in some ways similar to that from Chichén Itzá. Maya peoples, for example, continue to be photographed posed with artifacts or architectural features, and frequently standing next to a stele or the site's outer wall. And, despite the extensive photographic documentation of artifacts and features, there exist few if any photographs of the field laboratory.

Nevertheless, there are significant differences between the photographs taken at the two sites. Perhaps most notably, in the Mayapán corpus, photographs of individuals at work are almost absent. With only a few exceptions, individuals are shown either purposefully staged or at rest—not excavating, drawing, or photographing. Further, the vast majority of published photographs omit people. Throughout the extensively illustrated Mayapan, Yucatan, Mexico (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962) and The Pottery of Mayapan (Smith Reference Smith1971), only three photographs show humans. A photograph of a modern Maya house includes three barely visible individuals sitting outside its door (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, fig. 17e). A photograph of a staircase seems accidentally to include a person with his back to the camera walking away from the feature (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, fig. 20g). And a photograph of a wall includes an individual standing next to it, perhaps for scale (Pollock et al. Reference Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962, fig. 22e). Travis Parno (Reference Parno2010, 126) has suggested that this tendency to exclude people from archaeological photographs is part of a broader twentieth-century trend of depicting the products rather than the process of archaeology. Among other consequences, such photographs suggest that people are either absent from, or incidental to, archaeological sites.

More recent research: 1958–2000

The institutional period ended when the CIW terminated its research programme in the Maya area. Yet archaeological work in the region continued. Over the next half-century, archaeological projects became more numerous and more diverse. Theoretical perspectives broadened and new technologies emerged. Further, projects became more focused on answering wide-ranging anthropological questions, though often using the methods designed, and data collected, by earlier CIW projects (McKillop Reference McKillop2006, 51).

The Cobá Archaeological Mapping Project

Carried out over 20 months of fieldwork in 1974 and 1975, the Cobá Archaeological Mapping project (CAMP) sought to ‘define the settlement patterns of a Maya metropolis’ (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Kintz and Fletcher1983, 4). Directed by William J. Folan and George E. Stuart, the project consisted primarily of survey and mapping, but also included documentation of stelae and murals. Fieldwork was conducted in collaboration with Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), which excavated and reconsolidated part of Cobá's site centre. Valery Fadziewicz recorded most of the CAMP photographs, which appeared in the project's final report Cobá: A Classic Maya Metropolis (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Kintz and Fletcher1983).Footnote 7

Because CAMP did not conduct its own excavations, there are no photographs of excavation units or artifacts. Many of the published photographs depict instead the process of survey and mapping, including the difficulties associated with working in dense vegetation. Several photographs, for example, document how structures and features looked when first encountered during survey, before being cleared of vegetation. In stark contrast, other photographs document how the site centre looked after INAH excavation and reconsolidation. Such juxtaposition of images suggests that archaeological sites are not static but constantly in flux, and that their life histories are ongoing and ever changing (see Ashmore Reference Ashmore2002 for a discussion of the life histories of places).

Further, the published CAMP photographs depict Maya peoples, but in a very different manner from the CIW photographs. In almost all CAMP photographs, Maya peoples are shown at work rather than purposefully posed. There are no staged images of Maya individuals next to ancient Maya sculpture or architecture. Instead, individuals are shown completing mundane tasks unrelated to archaeology. A tailor is shown sewing clothing (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Kintz and Fletcher1983, fig. 10.3), a woman is shown making tortillas in her kitchen (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Kintz and Fletcher1983, fig. 9.1) and another woman is shown working in the yard outside her house (Folan et al. Reference Folan, Kintz and Fletcher1983, fig. 7.2). The CAMP photographs thus capture the actions of Maya peoples rather than solely their appearances.

The Selz Foundation Yaxuná Project

About a decade later, the Selz Foundation Yaxuná Project, directed by David Freidel and others, aimed to understand better the chronology of Yaxuná and its relationship with nearby sites, including Cobá and Chichén Itzá. Between 1986 and 1996, project members surveyed, mapped and conducted extensive excavations. Project photographs appeared in dissertations, publications and in the project's final report, Archaeological Investigations at Yaxuná, 1986-1996: Results of the Selz Foundation Yaxuna Project (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010).

Because of the project's size, duration and extensive number of associated publications, it is difficult to analyse all photographs taken by all project members. Nevertheless, the final report is instructive. It includes photographs of architecture, features such as burials and caches, and artifacts including several whole ceramic vessels. Not included are photographs of the archaeologists, of local Maya peoples, or of the archaeological process—of survey, excavation, or laboratory analysis. Only one photograph includes people, and shows four individuals excavating (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, fig. 5.218). Human traces—such as trowels (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, fig. 5.206) and knives (Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, fig. 5.251)—are occasionally included, primarily for scale.

Notably, the photographs show archaeological contexts and artifacts at different stages of excavation. Burials, for example, are shown before excavation (e.g. Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, fig. 5.180) and also during excavation with exposed offerings and human remains (e.g. Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, figs 5.181 & 5.182). Individual artifacts are also shown both in situ (e.g. Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, fig. 5.224) and also after being removed from the ground and cleaned (e.g. Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Freidel, Suhler, Ardren, Ambrosino, Shaw and Bennett2010, fig. 5.241). Among other insights, these photographs suggest that archaeology is a dynamic endeavour, and that objects are not static but mutable, variable and subject to change (see Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986 for a discussion of object biographies; and Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986 for a discussion of the social lives of things).

Current trends

Archaeological photography has changed rapidly over the last 20 years (see Morgan Reference Morgan2012, 46–55). The widespread availability of digital photography and of the internet has changed how people take and view photographs. Now, individuals can easily capture, share and view photographs almost any time, anywhere and without prior planning (Van House Reference Van House2011, 127–8). Technological advances have further allowed archaeologists to use photography for new purposes. For instance, archaeologists working in the Yucatan peninsula and beyond regularly use photogrammetry to transform two-dimensional photographs of structures and artifacts into three-dimensional models (e.g. Rissolo et al. Reference Rissolo, Lo, Hess, Meyer and Amador2017; Reference Rissolo, Hess and Herrera2019).

Beyond technological advances, theoretical developments have also led to novel uses and understandings of photography. To take one example, a recent focus on things has led some to suggest that photography offers a means to understand how objects themselves are sensuous and evoke emotions (Hamilakis et al. Reference Hamilakis, Anagnostopoulos and Ifantidis2009). Indeed, Pétursdóttir and Olsen (Reference Pétursdóttir and Olsen2014, 12, 13) have suggested that photography can help scholars ‘reconsider the place of sensation or affect in our engagement with things’ and question the ‘conviction that meaning and significance always radiate from the archaeologist/photographer rather than from the things (or images) in question’.

To take a second example, those practising engaged archaeology have suggested that photography can empower local groups. Some archaeological projects have equipped local community members with the technology and skills necessary to record their own photographs (Dedrick Reference Dedrick2018; Piccini & Insole Reference Piccini and Insole2013) and to create their own photogrammetric models (Haukaas & Hodgetts Reference Haukaas and Hodgetts2016; Karl et al. Reference Karl, Roberts and Wilson2014). Notably, the practice of providing local community members with cameras has a considerable history in cultural anthropology (e.g. Bellman & Jules-Rosette Reference Bellman and Jules-Rosette1977; Turner Reference Turner1992; Wong Reference Wong1999). Other projects have used photography to make archaeology a more inclusive endeavour. In one instance, project members requested copies of historical photographs from community members for local distribution and inclusion in publications (Diserens Morgan & Leventhal Reference Diserens Morgan and Leventhal2020). In another instance, outside the Yucatan peninsula, project members used 360° panoramas to facilitate interviews and collaborations with individuals who, for various reasons including decreased mobility, were unable to travel to the archaeological site or view the archaeological materials in person (Sesma Reference Sesma2021).

These and other scholars have used photography in efforts to share power more equitably with local communities and to make archaeology more inclusive and more relevant. Put differently, photography has been a useful tool for those practising engaged archaeology (Mickel Reference Mickel2021). But can insights from engaged archaeology enhance archaeological photography broadly? In other words, can an engaged archaeology perspective be a useful tool for all archaeologists taking photographs?

Insights from engaged archaeology

In 2010, Setha Low and Sally Merry identified several forms of anthropological engagement, including public education, collaboration and advocacy (Low & Merry Reference Low and Merry2010). Since then, several scholars have considered engaged archaeology specifically (e.g. Herr et al. Reference Herr, Lyons, Hays-Gilpin, Hays-Gilpin, Herr and Lyons2021; McAnany & Rowe Reference McAnany and Rowe2015; Mizoguchi & Smith Reference Mizoguchi, Smith, Mizoguchi and Smith2019; Smith & Ralph Reference Smith, Ralph and Smith2019). Although engaged archaeological perspectives vary, two general features commonly characterized the approach. First, engaged archaeology seeks not only to involve, but also to benefit members of local communities. Rather than just incorporating local voices into predefined research projects, engaged archaeological projects are ‘shaped by the values, visions, and agendas of the communities with whom archaeologists work’ (Mizoguchi & Smith Reference Mizoguchi, Smith, Mizoguchi and Smith2019, 229). Second, engaged archaeology recognizes that the study of the past takes place in the present; that archaeology influences and is influenced by living people; and that archaeological sites and artifacts are part of the contemporary world. In other words, engaged archaeological questions, methods and interpretations ‘clearly intersect with the contemporary world’ (Mizoguchi & Smith Reference Mizoguchi, Smith, Mizoguchi and Smith2019, 229).

Insights from engaged archaeology suggest at least three ways that all archaeologists might photograph differently. First, rather than abiding by tacit and often under-theorized photographic conventions, archaeologists can articulate what they choose to photograph, how and why, and consider whose interests such photographs serve. Over the last two decades, engaged archaeologists (Atalay et al. Reference Atalay, Clauss, McGuire and Welch2014; McGuire Reference McGuire, Hamilakis and Duke2007; McGuire et al. Reference McGuire, O'Donovan and Wurst2005) have encouraged scholars to ask a question originally posed by Rebecca Panameño and Enrique Nalda (Reference Panameño and Nalda1979): ‘Archaeology: for whom?’ This question offers a stark reminder that archaeology is more than a ‘selfless search for knowledge’ (McGuire Reference McGuire, Hamilakis and Duke2007, 9). By asking ‘photography for whom?’, archaeologists can remain cognisant that photography, like research more generally, is not a neutral endeavour and that photographic choices should be both thoughtful and explicit.

As part of this effort, archaeologists can also devise new ways to use photography to benefit members of local communities. To take one example, the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project, co-directed by the author, hired a professional photographer to take photographs for community members. Located in the Yucatan peninsula, Punta Laguna is a contemporary village, an archaeological site, a spider monkey reserve and a tourist attraction owned and operated by Maya peoples (Kurnick Reference Kurnick2019; Reference Kurnick2020; Kurnick & Rogoff Reference Kurnick and Rogoff2020). Perhaps not surprisingly, community members asked the photographer to record images of the tourist experience for use in promotional materials such as brochures. Importantly, community members retain control over these images.

Second, engaged archaeology's focus on the values and practices of living people suggests that archaeologists devise appropriate ways to include human beings in their photographs and thereby demonstrate that people are integral—rather than incidental—to archaeology and archaeological sites. Indeed, omitting people from archaeological photographs is problematic. As Parno (Reference Parno2010, 129) notes, doing so suggests that the archaeological record exists independently of archaeologists and their collaborators, a ‘position that ignores the entanglements of practice and results’. Further, by excluding humans, archaeologists risk fetishizing the objects they photograph. Put differently, archaeological photographs that omit people can unintentionally sustain and naturalize commodity fetishism—the misunderstanding of social relationships as relationships between things (Marx Reference Marx, Engels, Moore and Aveling1906, 83)—by seemingly creating ‘autonomous objects, divorced from the [social] relationships, flows, and connections that have led to their constitution’ (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2015, 721). Like some other projects, the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project is actively experimenting with ways of incorporating people and their traces in its archaeological photographs, including intentionally showing hands, feet, tools, and tarps (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Photographs of an empty cist, mid-excavation, at the site of Punta Laguna. The bottom photograph breaks with formal conventions by including the feet of the individuals excavating the cache and part of the tarp used to modify the lighting. (Photographs: David Rogoff.)

Finally, the understanding that archaeological sites and artifacts exist in the present suggests that scholars purposefully include aspects of the contemporary world in their photographs. Scholars may also choose to record what James Scorer (Reference Scorer2017) terms images of pleasure. As Scorer argues, traditional archaeological photographs often limit sites’ political efficacy by relegating them to the past and fetishizing them as places of awe and reverence (see also Gordillo Reference Gordillo2014). As he laments, ‘the ancient ruin continues to be photographed as an aura-laden, ethereal site of decay that is lost in time’ (Scorer Reference Scorer2017, 143). But images of pleasure, ‘images that convey a sense of fun and play with and at ruins, dismantle their aura, making them politically pliable once more’ (Scorer Reference Scorer2017, 160). Several photographs of the tourist experience at Punta Laguna fit Scorer's definition of images of pleasure (Fig. 9). These photographs demonstrate that archaeological sites do more than provide information about the past. They can, among other capacities, facilitate cultural revitalization (Lopez-Maldonado & Berkes Reference Lopez-Maldonado and Berkes2017), provide livelihoods for descendent communities (Beitl Reference Beitl2005), and be spaces of political resistance (Kurnick Reference Kurnick2019). In short, images of pleasure demonstrate that archaeological sites and artifacts are dynamic and politically efficacious parts of the present-day world.

Figure 9. Tourists canoeing across the Punta Laguna lagoon. (Photograph: Conrad Erb.)

Conclusion: photography beyond engaged archaeology

Photographs are contradictory. They are simultaneously objective and subjective, stable and ever changing, and simultaneously make significant and devalue their subjects. Photographs are also constructive. Rather than simply recording the past, photographs help shape it. Perhaps not surprisingly, photography has proved a malleable tool for archaeologists. Those studying the past have used photography to bolster diffusionist theories, to document ancient structures and artifacts and to facilitate collaboration with, and empower, local groups. This article has argued that scholars can also use photography to emphasize that archaeology is a decisively human and necessarily political endeavour, and that archaeological sites and artifacts are dynamic parts of the contemporary world.

More broadly, perhaps archaeologists can use photography to help change conventional conceptions of history. Traditionally, scholars have understood time as linear and directional, and thus associated with either progress or decline (Lucas Reference Lucas2005, 9–15). As Benjamin (Reference Benjamin and Redmond1974, pt. XIII) notes, the ‘concept of the progress of the human race in history is not to be separated from the concept of its progression through a homogeneous and empty time’. Benjamin critiqued such conventional understandings of time and argued instead that time periods exist concurrently, rather than progress sequentially. For him, temporal moments are comprised of variable impositions and erasures of physical remnants of different time periods. Benjamin thus understood time as a palimpsest and human history as a montage. As he wrote, ‘it's not that what is past casts light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation’ (Benjamin Reference Benjamin, Eiland and McLaughlin1999, 462). Benjamin thus encouraged scholars to understand history dialectically rather than linearly (Olivier Reference Olivier2004, 204).

By emphasizing rather than overlooking the fragmentary nature of photography, archaeologists may be better able to represent the past dialectically and thus move beyond problematic, linear notions of progress and decline. Archaeologists can purposefully juxtapose in the same frame objects made at different times in the past. Archaeologists can also purposefully juxtapose in publications photographs recorded at different times. Because photographs are necessarily temporal, spatial and visual fragments, they can effectively depict the past as a patchwork of moments and mosaic of overlapping temporalities. Put differently, it is perhaps through photographs that archaeologists can do what Benjamin (Reference Benjamin and Redmond1974) refers to as exploding the continuum of history.

Acknowledgements

Research on photography and engaged archaeology in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico was conducted as part of the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project, co-directed by David Rogoff, and funded by the National Science Foundation (Award No. 1725340) and the University of Colorado Boulder. I would like to thank Arthur Joyce, David Rogoff, Nicholas Puente, and three anonymous reviewers for reading and commenting on earlier versions of this article. Any errors are my own.