In 2015, booing and heckling mid-performance at Covent Garden reverberated in classical music circles around the world. Never before, pronounced the London critics, had they seen an English audience driven to shout during the performance the way audiences on the continent do. Typically, we are assured, Londoners have the good manners to wait until the curtain call to voice their malcontent. The offending production was Damiano Michieletto's new staging of Rossini's French grand opéra Guillaume Tell for the Royal Opera House (ROH). Michieletto updates Schiller's story of the fourteenth-century Austrian oppression of the Swiss people to a non-specific twentieth-century occupation by a brutal military force. During the open dress rehearsal, the audience erupted into jeers and shouts during the ballet in the third act when a group of soldiers singled out a young woman from the chorus and sexually abused her. While the size and scope of the critical response to Michieletto's Tell was exceptional, the rape scene itself is not. Representations of sexual violence proliferate on opera stages, especially in productions that can be categorised with that much-maligned moniker Regietheater. Regietheater productions share a disregard for an opera's specified stage directions and mise en scène in favour of directorial interpretation and expression that tends to draw parallels between old works and contemporary ideas.Footnote 1 Yet Regietheater, though defined in part by unconventionality, has developed its own set of conventions and a common currency of violence, sex and nudity.Footnote 2

This article considers the relationship between war and sexual violence in four Regietheater productions of canonic operas, including Michieletto's Guillaume Tell. The other productions are: Tobias Kratzer's 2019 production of Verdi's La forza del destino for Oper Frankfurt, in which the third act takes place during the Vietnam War; Tilman Knabe's 2007 production of Puccini's Turandot for the Aalto-Theater Essen, set in a non-specific contemporary authoritarian state; and Calixto Bieito's 2000 production of Verdi's Un ballo in maschera for the Gran Teatre del Liceu, set in a non-specific contemporary police state.Footnote 3 All four productions take place under military rule, either amidst combat or occupation, and feature acts of sexual violence supported and condoned by military structures. Staging sexual violence in wartime operas is not merely a result of Regietheater's economy of shock and scandal; these stagings frequently enact cultural anxieties about war and occupation and about the opera canon itself. Representing rape in wartime operas can function to challenge and critique the normalisation and valorisation of warfare on operatic stages. But there are risks and drawbacks to putting rape on stage. Through analysis and comparison of these four productions, I explore the stakes of staging sexual violence in the opera canon today.

I will make the distinction throughout between an opera's ‘written text’ and its ‘performance text’. Following David Levin, I adopt Roland Barthes's distinction between texts and works, and conceive of operas as the former insofar as they are ‘mobile, plural, and furtive, resistant to encapsulation and commodification’.Footnote 4 Levin distinguishes between what he calls the ‘opera text’, comprising the score, libretto and stage directions, and the ‘performance text’, for operas in performance.Footnote 5 While I am indebted to Levin for this framework for discussing opera in production, I prefer ‘written text’ to ‘opera text’ because I believe that the category ‘opera’ exists in performance just as much as (indeed, more than) it exists on the page. It is for this reason that I refer to the four productions of this article together as ‘wartime operas’ even though two of them acquire wartime settings only in their performance texts.

Tropes of wartime rape on the opera stage

Sexual violence has always occurred alongside war, but attitudes about the relationship between these atrocities has shifted over time. In 1977, an amendment to the Geneva Conventions explicitly outlawed the rape of victims of armed conflicts, but it was only in the 1990s that, in response to a number of specific conflicts, international governing bodies began to recognise the full scope of wartime sexual violence.Footnote 6 In 1993, instances of widespread gang rape and sexual slavery of Muslim women in Bosnia and Herzegovina were classified as crimes against humanity for the first time. Then in 1998, the United Nations ruled that rape could be an element of genocide, after witnessing how during the Rwandan Genocide Tutsi women were systematically raped in an attempt to destroy their ethnic group. Finally, in 2008, the United Nations adopted language that categorises rape and sexual violence as war crimes. These landmark decisions have led to gradual acceptance of the idea that sexual violence is not a side-effect or coincidence of war, but a weapon of war employed systematically in military conflicts for purposes up to and including genocide.

The idea that sexual violence could be a weapon of war came to wide public attention during the Balkan Conflict, and these four wartime opera productions capitalise on the popular association between rape and war that followed. In her ground-breaking volume on the rape camps in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Alexandra Stiglmayer argues that although popular wisdom has typically excused wartime rape as a natural result of enforced chastity among young soldiers, we might better understand the motivations for these rapes in terms of existing structures of misogyny. She writes:

[The soldier] rapes because he wants to engage in violence. He rapes because he wants to demonstrate his power. He rapes because he is the victor. He rapes because the woman is the enemy's woman, and he wants to humiliate and annihilate the enemy. He rapes because the woman is herself the enemy whom he wishes to humiliate and annihilate. He rapes because he despises women. He rapes to prove his virility. He rapes because the acquisition of the female body means a piece of territory conquered.Footnote 7

Stiglmayer's justifications here touch on issues of objectification, dehumanisation and male dominance common to many feminist interpretations of wartime rape. Indeed, the feminist scholars who populate this article have shaped popular understandings about the nature of rape and its interaction with military conflict, and their interpretations of wartime rape in terms of power, dominance and misogyny are at work in the operatic representations of sexual violence by Michieletto, Bieito, Kratzer and Knabe.

Many nineteenth-century operas are set at wartime. British opera critic Hugo Shirley's assertion that French grand opéra ‘tended to favour history and its battles for the scenic opportunities they afforded rather than for the lessons they taught’ may be suitably applied to nineteenth-century opera genres more broadly.Footnote 8 Regietheater also loves a wartime context, but these are more often stark and dystopian modern-day war or occupation settings. Amplifying and even inventing violence in productions of canonic operas can function as a criticism of opera's tendency to dramatise scenarios of human suffering for the sake of entertainment. Treating these stories seriously (in the opinion of many critics, too seriously) points out and problematises opera's predominantly aesthetic preoccupation with stories of war and oppression. Sexual violence is proving to be a popular way for directors to achieve this level of increased seriousness. But in recent years, the sexual violence that pervades the opera canon has become more visible and increasingly political.Footnote 9 Staging sexual violence in wartime operas can make the setting more realistic and can allow directors to represent suffering on a more intimate scale, but such practical justifications do not tell the whole story.

Through analysis of these productions, I have noticed several emergent tropes in the way wartime rape is represented on the contemporary opera stage, which I refer to as: Rape as Performance, Alienation, Power and Control, and Dehumanisation of the Other. These four tropes offer different lenses through which to consider representations of wartime sexual violence, and each has its own theoretical backdrop. Whereas Rape as Performance is primarily focused on the way the representation of rape impacts the stories of the operas, the other tropes have more to do with the way these stories are seen, heard and understood by their audiences in terms of ideas from scholarship on Regietheater, feminist conceptions of sexual violence, and intersectional politics. Shifting between these different lenses allows my analysis to be nimble and to navigate concerns about the story being told on stage and the implications of the representations to their audiences.

Rape as performance

Catherine MacKinnon describes the sexual violence at the Serbian rape camps in Bosnia and Herzegovina as representing ‘live pornography’. In addition to filming the rapes, MacKinnon claims, the Serbian forces would invite their fellow officers to come and watch them. One soldier compared this experience to going to a movie theatre.Footnote 10 Michieletto's Guillaume Tell and Kratzer's La forza del destino both stage sexual assaults in the context of performance and evoke these real-world stories.Footnote 11

In Act III scene 2 of Guillaume Tell, the libretto specifies that during a celebration of the anniversary of Austrian rule, the Austrian soldiers force some of the Swiss women to dance.Footnote 12 This is an act of violence and coercion predicated on sex, and it is also a performance. In Michieletto's production, the undercurrents of sexual coercion are brought to the surface: in place of a dance, he stages the sexual assault of one Swiss woman. At the beginning of the ballet movement, Governor Gessler, the Austrian Commander, whispers something to the captain of his guard, who, with the help of a few other soldiers, selects a Swiss woman from the chorus and drags her forward. They offer her a glass of champagne, and when she refuses it and runs, about half a dozen soldiers surround her and force her to drink while they pour their own champagne over her head. She runs again, and this time is caught by a soldier sitting at the table who holds her in his lap while others grope her and try to reach up under her dress. Now when she breaks free, it is Rodolphe, the captain of the guard, who catches her and brings her to Gessler. Gessler initially presents a veneer of kindness, touching her shoulder as if to comfort her and moving her wet hair out of her face. He draws his gun and taunts her with it playfully. In the presence of the gun, the terrified woman momentarily stops fighting. Gessler tries to kiss her mouth, and she pushes him away. Furious, he gestures for his men to take her back over to the table. They force her onto the tabletop and strip her, obscuring her from the audience with their bodies. She stands up and wraps the tablecloth around herself, crying and shaking her head no. The men jump and dance around below her, beating their fists on the table in unison. They seize her, pull her to the ground and pile on top of her, pulling the cloth away. Suddenly, Tell appears in the fray as if from nowhere, and the woman escapes off stage.

This scene feels like a performance because it takes the place of a ballet and is scored by music that functions as dance music in the world of the opera. But Michieletto's production also lays bare the real-world elements of performance in wartime rape. While the woman is assaulted by a group of soldiers, the stage is filled with a much larger chorus comprising the whole company of Gessler's men. Gessler presumably orders this assault when he whispers into Rodolphe's ear at the beginning of the ballet. In the context of this scene, this order may be readily understood as a means for Gessler to raise the morale of his men. For these Austrian soldiers, the audience on stage is important: the assault serves both to entertain the other soldiers and to terrorise and threaten the Swiss chorus. This element of the rape scene is a part of what makes it so difficult to watch. We in the opera's audience are made to be spectators of this abuse that is being self-consciously performed for spectators. We find ourselves suddenly and uncomfortably sharing the perspective of the soldiers who are titillated by the abuse.

Tobias Kratzer's 2019 production of Verdi's La forza del destino for Oper Frankfurt also stages sexual violence in the context of performance, but with a significantly different tone. The third act of this opera is set during the eighteenth-century War of the Austrian Succession, but Kratzer transposes the action to the Vietnam War. Act III scene 3, in which the soldiers have a moment of rest and recreation, becomes for Kratzer a performance given for the troops by a trio of Playboy Bunnies who are airlifted in, in an allusion to a similar scene in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now.Footnote 13 In a performance area amidst the transfixed soldiers, the women don rubber masks and play out a short mime scene. Two dancers wearing JFK and Marilyn Monroe masks flirt over a birthday cake until they are interrupted by a dancer in a Nixon mask. Nixon takes the cake from Marilyn and shoves it into JFK's face, who collapses. The woman who had been wearing the JFK mask trades it in for an Asian conical hat and slinks around the stage menacingly as the soldiers boo. The dancer in the Marilyn mask takes it off and hands an oversized strap-on dildo to Nixon. As the chorus bursts into a refrain of ‘viva, viva la pazzia che qui sola ha da regnar’ (‘long live the madness of war’), Nixon grabs the dancer in the conical hat by the hips and simulates raping her, while the third dancer stands behind Nixon with a hand on her shoulder, egging her on. The soldiers dance and thrust along with the mock rape as they sing, and they burst into laughter and applause as the number concludes.

Like the rape scene in Michieletto's Guillaume Tell, this is an instance of rape being used in performance to raise morale. However, whereas the Tell rape appeared to excite and titillate the soldiers because they found the woman being raped sexually desirable, the Forza mock rape excites and titillates because the performers are scantily clad women. They do not pretend that the rape they act out is sexy, rather the costumes and props are comic and crass. What this display shares with the Tell ballet is a basic assumption that sexual violence is an effective tool of peer bonding for soldiers. Susan Brownmiller, in her landmark 1975 book on rape, suggested that gang rape may even have been one of the earliest forms of male bonding.Footnote 14 Though Tell's attempted rape and Forza's rape skit are drastically different in tone, both rely on our recognition that sexual violence, and gang rape in particular, can function to sow solidarity among the perpetrators.Footnote 15

Alienation

The impact of Regietheater productions of canonic operas often depends on a disjunction between an audience's expectation and the production's realisation of a scene. Studies of Regietheater frequently connect this aesthetic of defamiliarisation with Berthold Brecht's alienation or estrangement effect (Verfremdungseffekt).Footnote 16 Joy Calico explains that in nonliteral stagings of canonic operas, the experience of estrangement comes from the disruption of expectation, and specifically the ‘rupture between what is seen and what is heard’.Footnote 17 The goal of estrangement is not only the disorientation of thwarted expectations, but also the re-cognition that follows. Regietheater, like Brecht's epic theatre, bestows agency on its spectators by asking them to rethink what they have previously taken for granted. This kind of spectating can be pleasurable, and it can also be used to forward a socio-political critique.Footnote 18 In each of these four wartime productions, the potential political scope of Regietheater estrangement can be seen most clearly in three large ensemble scenes that represent nationalistic sentiment as violent jingoism.Footnote 19 Regietheater in general frequently takes aim at excessive nationalism especially, in the German context, through use of Nazi iconography, as is the case in two of the productions here.Footnote 20

The aforementioned scene in Kratzer's La forza del destino is part of a large ensemble set piece. The soldiers drink and relax in the camp while merchants sell their wares and the Playboy Bunnies offer amusement. The musical numbers on the whole are rollicking and cheerful. One of the Bunnies is a singing role – Preziosilla, who appears twice in the opera to encourage the men to enlist and then enjoy military life. In this scene she wears a stars-and-stripes corset teddy in addition to her Playboy Bunny trimmings, and she represents an unflattering view of American patriotism and militarism. There are two chorus numbers in the third act in which Preziosilla leads the soldiers in a gleeful celebration of war. The first is the Tarantella, ‘Nella guerra è la follia’. This is the scene discussed above, in which Preziosilla and two other women perform a skit in which Nixon rapes a Vietnamese person to the cheers and laughter of the crowd. The second Preziosilla chorus number is ‘Rataplan’, in which the soldiers sing, ‘le gloriose ferite col trionfo il destin coronò … La vittoria più rifulge de’ figli al valor’ (‘your glorious wounds will be rewarded by your triumph … Victory shines brighter for the courageous soldier’).Footnote 21 During this chorus, Preziosilla brings a group of Vietnamese POWs forward to sit cowering amidst the American soldiers. She produces a revolver, loads the chamber with a single bullet, and spins the cylinder. Surrounded by the company of soldiers, she selects one of the Vietnamese prisoners, drags him forward, aims and pulls the trigger, but the gun does not fire. Then she passes the gun to another soldier and gestures for him to follow suit. He hesitates, but the other soldiers egg him on and pump their fists in the air. He aims and shoots, and the prisoner falls dead. The most explicit statements of pro-war sentiment in this scene are thus undercut in Kratzer's production by depictions of violence: first a shared rape fantasy, then a brutal execution. The cheerful strains of folk dances in the Tarantella and the victorious martial motifs in ‘Rataplan’ align with the experiences of the soldiers and of Preziosilla in their froth of jingoistic pride and anger. But for an audience shocked by the presence of these violent depictions, the music here is jarring. The affect of celebration and triumph in these numbers sits uncomfortably with the scenes they depict in Kratzer's production. And this discomfort asks us to think more critically about the patriotic pro-war sentiments that these musical numbers have always advanced.

While the rapes in Un ballo in maschera and Turandot happen in private, as will be discussed below, both of these productions also feature chorus scenes whose celebratory music is made dark and menacing by the violence of their stagings. Both Bieito's Ballo and Knabe's Turandot are set in fascist police states. In the Act I finale of Ballo, King Gustavo (Ricardo) is undercover, seeking out the advice of the fortune teller Madame Arvidson (Ulrica).Footnote 22 When his identity is revealed, the chorus enters singing ‘Viva Gustavo’ and then a triumphant hymn to the glory of their leader, ‘O figlio d'Inghilterra’. As soon as the full crowd is amassed on stage, they perform a group Sieg Heil to Gustavo. Their ringing cries of ‘Gloria’ become unsettling when accompanied by the Nazi salute. Bieito's cynical opinion about this kind of nationalistic fervour for the monarch is clear.

Turandot's second act ends with a similar scene. The foreign prince, Calaf, has successfully answered all of Princess Turandot's riddles and is now primed to marry her as long as she cannot guess his name by the next morning. The reigning Emperor makes a statement lending his support to Calaf, and the gathered crowd sings praises to the Emperor's wisdom and goodness in ‘Ai tuoi piedi ci prostriam’. In Knabe's staging, the Emperor exits while the chorus is singing, and in his absence, it becomes clear that the crowd is not addressing the Emperor at all, but Calaf. The crowd rushes forward, through barriers set up by the military police, and they lift Calaf up on their shoulders. He leads them in a Sieg Heil salute. As in Ballo, this moment of relatively uncritical musical patriotism for a leader becomes fanatical in performance. But Calaf is a different kind of leader to Gustavo: he is a foreign conqueror. Ping-hui Liao has pointed out that in this scene, the crowd expresses their enthusiastic desire ‘to be ruled over by the foreign Prince’.Footnote 23 Puccini and his librettists have represented a bloodthirsty and irrational people who ‘cannot free themselves from their evil past but must seek a solution from outside’.Footnote 24 The imperialist message is clear: Calaf's influence ‘civilises’ Turandot and her people, freeing them from their backward, primitive ways. The fervent support of the crowd for the conquering foreigner is further amplified in Knabe's production because this final chorus of the second act, which in the written text addresses the old emperor, now exalts Calaf instead.

These three chorus scenes from Forza, Ballo and Turandot feature conventional operatic use of the chorus, but Kratzer, Bieito and Knabe mine a darker message out of these scenes, which they represent by comparison with real-world fascism.Footnote 25 This effect is particularly pronounced in Turandot because the presence of Nazi iconography sits uneasily in the dramatic context of this staging. Knabe's setting does not appear to be a particular real-world location or moment in history.Footnote 26 And the relationship between the kingdoms of China and Tartary is unclear: the principal characters are not racially differentiated based on their Chinese or Tartar origin. The evocation of Nazism with its hyper-racist brand of fascism is odd in this context. And within the world of the opera, how does the Chinese crowd immediately know what to do when this foreign conqueror makes this gesture? In Ballo, we might imagine that Gustavo's military leaders taught and enforced the salute among the citizenry, as in Nazi Germany. But Calaf has just arrived in the kingdom of a foreign power. The Sieg Heil in Turandot seems to operate entirely as a signifier of fascism for the audience in Essen.Footnote 27 Its dramatic incoherence with the fictional world of the opera pronounces the effect of alienation for an audience that is moved by the symbolism of the Sieg Heil but unable to neatly reconcile it with Turandot's written text or even Knabe's production.

The ballet movement in Michieletto's Guillaume Tell can also be understood in terms of the estrangement effect. Ballet movements in general are popular sites for directorial addition and reinterpretation. And as Micaela Baranello has pointed out, ‘the staging of the violent, often sexually suggestive abuse of women during ballet interludes, usually to jaunty music, has become a virtual obsession of recent productions’.Footnote 28 Baranello cites this production of Tell among her examples of this phenomenon, but it is important to note that the written text of Guillaume Tell also features elements of estrangement between music and libretto, even prior to Michieletto's intervention. This movement in the drama is a serious one for the Swiss people, with whom the audience's sympathies lie: we watch Tell's people being forced to dance for and with the Austrian soldiers. The music does not reflect this element of the scene. Instead, it is light-hearted, folk-inspired dance music. Michieletto's production certainly pushes this disjunction between light-hearted music and troubling stage action much further, but the difference with Michieletto's violence is one of degree and not kind. Sarah Hibberd argues that Michieletto's approach actually takes the audience back to the Paris Opéra at the time of Guillaume Tell's premiere in ‘the use of pantomime in the ballet sequences; the contrast of music and dramatic situation in shocking juxtaposition, and the attempt to bring home to a modern audience the dark undercurrent running through the ballet sequence’.Footnote 29 Michieletto engages with details not just of Tell's libretto, but of Rossini's music in this ballet interlude in a sensitive and compelling way, even given the estrangement effect. His approach to staging this scene seems to imply that the orchestral music of the ballet is music that the characters on stage can hear. It is functional music which Gessler calls for, and to which the Austrian company is relaxing and celebrating at the expense of the Swiss people.

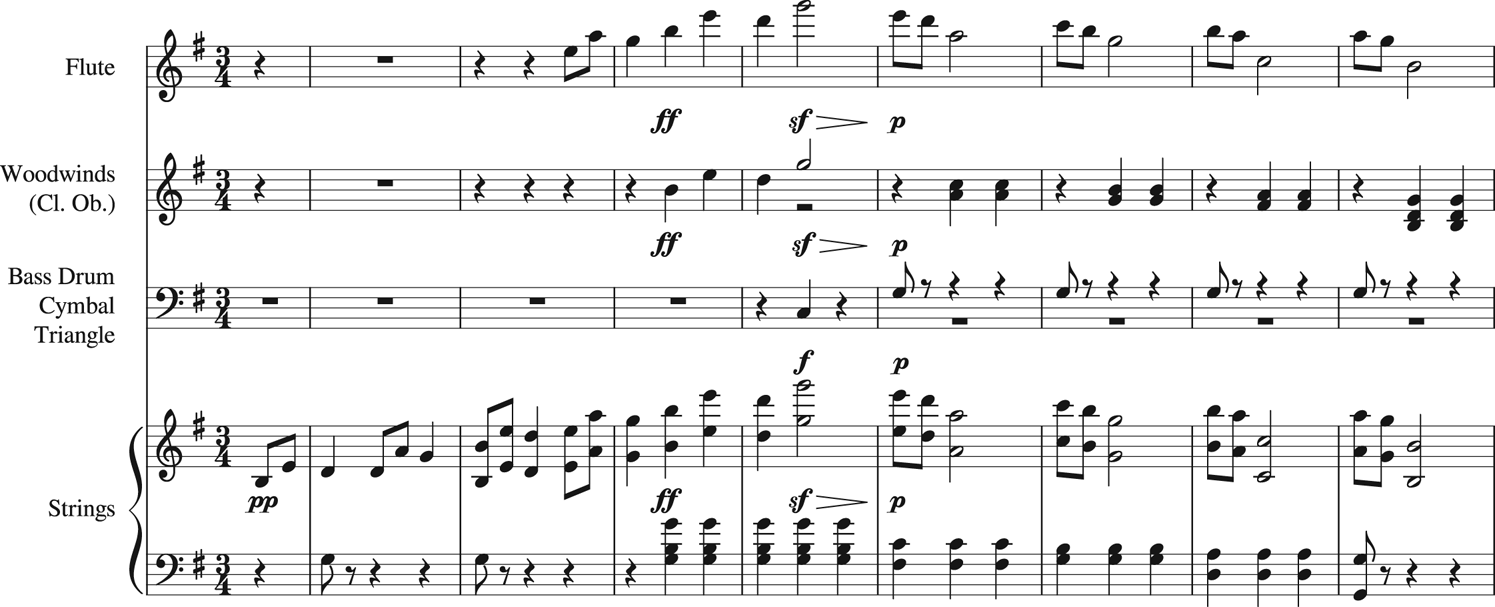

Michieletto capitalises on the general character but also on specific features of Rossini's score to unite his staging and concept with the music in Act III scene 2. The connection is particularly sophisticated when Gessler interacts with the Swiss woman whom his men are tormenting. When the woman is presented to Gessler, the orchestral texture thins, and a short unison scalar passage of descending semiquavers in the strings (the first bar of Example 1) corresponds with Gessler running his fingers down the woman's arm. In the next bar, a high-pitched tremolo figure for the flute and first violin scores the woman shivering in response. Then the same descending figure accompanies Gessler stroking her arm again before this figure is picked up by the rest of the strings and woodwinds. Michieletto is depending on a Regietheater technique in which staging choices are legitimated by their alignment with musical structures.Footnote 30 The concordance emphasises that while this music has an estranging effect on the audience and the Swiss characters, it fluently scores the actions and motivations of the Austrian soldiers.

Example 1. Rossini, Guillaume Tell, Act III scene 2, no. 16, 16–21 bars after Reh. C.

Gessler continues to be attuned to the music of Rossini's ballet through the remainder of this scene. The following section, Allegro Vivace, is a little waltz that begins with an eight-bar theme in the strings and woodwinds that hurtles up an arpeggio to a towering peak emphasised by a cymbal crash on the second beat of the bar, before winding its way back down the scale to repeat (Example 2). In the introduction to this new section, Gessler draws his gun from his holster behind the woman's back; the musical change corresponds with a change in stakes when Gessler's gun appears. As the crashing top note in the first occurrence of this phrase sounds, Gessler thrusts his gun suddenly in front of the woman's face, and she screams. He pulls the gun back to himself and out of her sight as the melody winds back down to its starting point. On the repeat of the theme, Gessler does the same thing with his other hand, surprising the woman with the gun again on the same emphasised beat. A different eight-bar theme is now introduced, and during this time Gessler tries touching the woman all over, as if testing her. Terrified after seeing his weapon, she stands still. Then, the original arpeggiated melody returns twice more (17 bars before Reh. A in the Allegro Vivace). The first time, the emphasised beat at the top of the arpeggio coincides with Gessler suddenly grabbing the woman's face. He holds her tightly and slowly moves in to kiss her lips. The phrase repeats for a final statement, and this time the woman, in a desperate attempt to escape, pushes Gessler away just before the accented beat. It is possible that this was simply a small mistake in the execution of the complicated choreography of this scene, but I interpreted her timing as an interruption of his next intended move, which likely would have happened cleanly on beat two. It begins to feel as if, in the world of the opera, Gessler is intentionally mapping his movements onto the dance music he hears for fun. He certainly conceives of his torture of this woman as a game; is it also a dance?

Example 2. Rossini, Guillaume Tell, Act III scene 2, no. 16, beginning of Allegro vivace.

Gessler's ability to interact meaningfully with the music in this scene extends to his men in the next portion of the staging. When the woman stands up on the table wrapped in the tablecloth, the waltz concludes and the next section begins, a Presto in 2/4. This section repeats the pastoral music from the beginning of the Pas de soldats, but faster. At the new tempo, this already rapid-fire melody feels increasingly frenetic. The soldiers pound the table rhythmically with the crotchets, dancing to the music as they keep time with their fists. In this moment, it is especially clear that the characters on stage can hear the music; they are able to dance and play tabletop percussion on the beat. Within the world of the opera, this music is being played for the Austrian soldiers, because to their minds this scene is a celebration and a bit of fun. The music does not narrate the story from our perspective; in fact, it stands in opposition to our experience of the mood of this scene. But there is one element of the sound world of the ballet that does align with the experience of the audience and of the Swiss spectators. Michieletto has the victimised Swiss woman contribute to the aural dimension of this scene as she grunts with exertion and screams, interrupting the oblivious frivolity of the dance music. By adding something new to the soundscape, the woman's vocalisations decentre music as the only sonic source of meaning in this scene. The uncomfortable juxtaposition of the soldiers’ celebration and the Swiss prisoners’ terror is translated into sound as these vocalisations of pain and fear punctuate and disrupt the dance music.

Power and control

Eileen Zurbriggen posits that war and rape are correlated because they are both supported and justified by what she calls the traditional or hegemonic model of masculinity. One of the dimensions of masculinity that she explores in relation to both war and rape is dominance/power/control. She cites a number of studies that have found that men with high levels of power motivation (a chronic concern with impact and control) were more likely to display coercive sexual behaviours, and were also more likely to enter a war and have success as soldiers.Footnote 31 Power motivation is a common and tangible element of the representations of war rapes discussed in these opera productions. When Governor Gessler orchestrates the rape of the Swiss woman in Michieletto's Tell, it is not just for the pleasure of his men: it is an implicit threat to the other Swiss people who are watching, and a reminder of their powerlessness. While rape is a crime against an individual, the meaning of rape in war is not individualistic. The women who are raped in armed conflicts are representatives of their ethnic groups and stand-ins for their husbands, brothers and fathers.Footnote 32 Their individual domination is a metaphor for the large-scale domination of their homes and people. In this way, martial rape is an act of terrorism toward the enemy group at large, used to maintain and express control.Footnote 33

Calixto Bieito's production of Verdi's Un ballo in maschera for the Gran Teatre del Liceu in 2000 features the rape of a young man by police in a military state. Though not strictly a war setting, this production is still closely related to the theme insofar as it shows state-sanctioned sexual violence as a tactic to punish civilian disobedience under a military government. It is relatively unusual to see a man depicted as the victim of rape on the opera stage, but this character's representation sexualises and objectifies him in a way that closely aligns him with the women who are more typically the receptors of operatic sexual violence. We are first introduced to the young man in a large ensemble scene at the home of the witch and fortune teller Madame Arvidson. In this production, Bieito has set this scene in a brothel and made Madame Arvidson its proprietor. The young man appears to be a sex worker. He is costumed in leather trousers and a shiny silver shirt unbuttoned and hanging off his shoulders. Throughout this scene, he is used quite literally as a prop; various characters physically move him around the stage as they caress his body. At the end of this scene, he gets on his knees in front of King Gustavo and steals Gustavo's wallet under the pretence of offering to perform fellatio.

The next act begins with a long orchestral interlude introducing the new setting: a dark field at the outskirts of town where the gallows are located. Amelia describes this as the place where ‘s'accoppia al delitto la morte’ (‘crime and death are joined together’). The young man from the brothel runs on stage, pursued by four police officers. They catch him, beat him and strip him naked. Three officers hold the young man down while the fourth lowers his trousers and rapes him. Anckarström (Renato), who in this production is the King's military captain, enters and watches from upstage. After the rape, another of the officers fishes the man's belt from his clothes and strangles him with it. The officers retrieve the stolen wallet from the dead man's trousers and deliver it to Anckarström as they leave the stage. Although Anckarström appears to be the only witness to the rape, the officers leave the naked body in the field. This public display demonstrates the power of the police to carry out retributive justice against civilians without consequences. The rape and murder may also communicate a direct threat to Madame Arvidson, the young man's employer, who was in some tension with Gustavo in the previous scene. Finally, this scene shows the audience further evidence of what Bieito thinks about the fanatical devotion paid to King Gustavo in the opera. The previous scene ended with a company Sieg Heil for Gustavo, and the next thing we see is a brutal act of sexual violence and murder enacted by the police on the orders of a military commander as punishment for petty theft of the King's property. Here, sexual violence is a tool of the military state to punish crimes committed against the King and to keep dissenters in line.

This scene in Bieito's Ballo portrays rape as primarily a means of asserting dominance and power. Susan Brownmiller uses the prevalence of rape within male prisons to support her argument that rape is not a crime of passion but of violence. Prison rape, she argues, is ‘an acting out of power roles within an all-male authoritarian environment in which the younger, weaker inmate … is forced to play the role that in the outside world is assigned to women’.Footnote 34 Brownmiller's argument here appears reductive in light of contemporary conversations about the imprisonment of transgender women in men's prisons, who we now know suffer sexual violence at much higher rates than men.Footnote 35 Yet Brownmiller's view of prison rape as primarily about violence and control rather than primarily about sex is still widely held, and is at work in the portrayal of the rape of this sex worker in Bieito's Ballo.Footnote 36 In this production, rape is a tool used to maintain the power dynamic in this exclusively male political structure. Bieito suggests that sexual violence exists alongside and intermingled with political violence. The ease with which his soldiers transition from rape to murder and Anckarström's utter lack of surprise suggest that the military system of Gustavo's Sweden does not meaningfully distinguish sexual violence from other means of control and punishment.

Dehumanisation of the other

Sexual violence can be understood as inherently an act of dehumanisation. Ann Cahill defines rape as ‘an act that destroys (if only temporarily) the intersubjective, embodied agency and therefore personhood of a woman’.Footnote 37 The dehumanisation and objectification inherent to sexual violence is reinforced in wartime settings as women are commonly perceived as representations of an enemy nation or race. Brownmiller describes the bodies of raped women during war as ‘ceremonial battlefields’ on which conflicts between men are played out in miniature.Footnote 38 The rape-as-war metaphor here portrays women as symbols more than people. We have seen already that the victims of rape and attempted rape in Ballo and Tell are both unnamed and non-singing supernumeraries who are introduced to the story for the purpose of being raped as symbols of the ravages of war. In Forza and Turandot, the dehumanisation inherent to rape is concomitant with dehumanisation on racial and political grounds. Sexual violence acts as a natural ally to racism when the goal is dehumanisation of the other.

The rape skit in Forza is an example of how using rape as a metaphor for war can be tied up with dehumanising narratives about rape victims. What begins as a bawdy burlesque crashes into a stunning display of sexualised racial animosity. The Forza rape skit depicts Nixon taking over from JFK – who is portrayed as flamboyant and feminine – and dominating the Vietnamese enemy. When the woman in the Nixon mask mimes raping the woman in the Asian conical hat, the unmasked Preziosilla stands at Nixon's shoulder, offering support. The rape is transparently symbolic: the woman who is raped represents the whole nation of Vietnam, or maybe the Vietnam War; the rapist is Nixon, America's final Vietnam president; and Nixon is being supported by Preziosilla dressed in the American flag. The reduction of Vietnam to a single costume piece alone reflects the dehumanisation at work in the way the Americans represent the enemy to each other in this scene.Footnote 39 Although in the written text Preziosilla is Roma, in Kratzer's production she is not marked as racially distinct from the soldiers. Instead, she is blonde and curvaceous, attired in an exaggeratedly patriotic Playboy outfit: an unflattering reflection of a commodified American patriotism.

Although the three dancers who perform this skit are all women, gender nonetheless weighs heavily on this representation. Inger Skjelsbæk has argued that war rape must be understood in terms of the masculinisation of the perpetrator and the feminisation of the victim. She writes, ‘the ways in which masculinization and feminization polarize other identities are intimately linked to the overall conflict structure, and it is this mechanism which can make rape a powerful weapon of war’.Footnote 40 While the rape fantasy represented here is an allegorical one, it is an unnamed, non-singing woman in a sexy costume who takes on the role of the Vietnamese enemy. Her already objectified body, which had moments before been titillating the amassed soldiers, easily transitions from a sexual object meant to draw the men's lust to a despised object meant to draw their hatred. To heighten the gendered dynamics of Forza's mock rape, the dancer in the Nixon mask wears a comically oversized phallus, and struts around the stage flexing her muscles. Nixon's supreme, symbolic masculinity is further accentuated in contrast with the effeminate and ineffectual portrayal of JFK. JFK's representation highlights how binary this conception of gender and power is: political and military might are synonymous with masculinity, and to fall short of the former is to relinquish the latter. The skit leverages the idea of rape as a vehicle to express hatred of the Vietnamese other by mapping racialised identity onto femininity.

Turandot does not feature the same racialised dehumanisation that is at work in the Forza rape skit, but in Knabe's production, Calaf dehumanises and ultimately rapes Turandot in order to achieve his political goals. Knabe's Turandot is set in a totalitarian state, whose ageing dictator is near death. Calaf, exiled from a foreign kingdom, wins Turandot's hand and thereby a seat of political power. Knabe states clearly in the programme that Calaf's desire for Turandot is about the power of her position, and not love; Calaf is not a ‘schmachtender Liebhaber’ (‘languishing lover’), but ‘ein raffinierter, hochstrategischer Politiker’ (‘a clever, highly strategic politician’).Footnote 41 In the final act of Turandot, after Calaf has answered the riddles and Turandot has failed to guess his name, Knabe sets the final scene in a small bedroom on an otherwise dark and empty stage. Everything until this point has taken place out in the open, under constant surveillance of guards and the populace. Now, Turandot and Calaf are alone. In the libretto, Calaf kisses Turandot despite her violent protestations. She pleads, ‘non profanarmi’ (‘do not profane me’), ‘mai nessun m'avrà’ (‘no one will ever possess me’) and ‘non mi toccar, straniero’ (‘stranger, do not touch me’). In Knabe's staging, Calaf throws Turandot down on the bed, kneels between her legs and rapes her. Whereas the stage directions in the libretto specify that Turandot is transfigured by the stolen kiss, Knabe's Turandot is broken and resigned through the opera's conclusion. This production cuts the portion of the ending when Turandot sings about her awakening to love, so she sings only a few short lines after the rape, including ‘onta su me’ (‘I am ashamed’).Footnote 42 As the chorus sings a climactic reprisal of the melody of Calaf's aria ‘Nessun dorma’, Calaf walks away from Turandot carrying a baby doll smeared with what looks like blood and afterbirth. He holds the child up triumphantly over his head on one side of the stage as the climactic music swells.Footnote 43

Both Knabe and the musical director Stefan Soltesz refer to Turandot as a vehicle for power in Calaf's eyes.Footnote 44 After the kiss, or in this case rape, Turandot tells Calaf that he has won his victory and that now he can leave. She does not understand that the rape itself is not the prize, it is simply politically expedient. It binds Turandot to Calaf and assures he will reign as Emperor in her father's place, and the resultant child ensures the continuing power of his political dynasty. Calaf wants to conquer Turandot, and he does this not just by outsmarting her but by impregnating her. During the war in the Balkans, likewise, the aggressors ‘used rape not only as a tool of war, but also to implement a policy of impregnation in order to further the destruction of one people and the proliferation of another – a policy of genocide by forced impregnation’.Footnote 45 Turandot is a vehicle for power for Calaf, and she is also a vessel for his politically legitimate heirs. To Calaf, Turandot is not a person with autonomy: she is only her bloodline and her fertile body. Turandot's dehumanisation is especially jarring because she is not only a named character, unlike the rape victims in the other productions, but the opera's eponymous character. Her immense power and agency from the opera's start are stripped away after Calaf answers her riddles. In the opera's final scene, after the rape, Calaf and Turandot pose in their wedding clothes as if for a portrait before Calaf walks away with the baby to celebrate his victory. Turandot stands motionless in her white dress like a photograph of herself reduced to a single purpose – providing legitimacy to Calaf's reign.

What's the harm?

The tropes above communicate cultural ideas about war and sexual violence. Through these tropes, Michieletto, Bieito, Kratzer and Knabe share critiques of masculinity, militarism and misogyny. But staging sexual violence is risky, and the act of representing atrocities on stage does not necessarily function as critique of those atrocities. Reviewers of Regietheater productions frequently condemn graphic depictions of rape in the same breath and with the same exasperated tone as they condemn nudity, toilet humour and drug use. But viewers and critics who equate staged depictions of rape with nonviolent spectacles perceived to be in poor taste fail to recognise the different stakes at play. When Michieletto's Guillaume Tell opened in London in 2015, many reviewers launched the familiar Regie criticisms, but there was also a refreshingly nuanced discussion about the stakes of staging sexual violence in opera.

Opera singer Catharine Woodward (Catharine Rogers at the time) made two public blog posts sharing her correspondence with then-artistic director of the ROH, Kasper Holten, detailing her qualms about the production after attending the dress rehearsal, which was open to industry professionals and friends of the company. The dress rehearsal featured a different version of the ballet scene than the one I analysed above. In the first version of the scene, the Swiss woman's naked body was exposed in full to the audience and the stage action included Gessler molesting the Swiss woman with his gun. Woodward submitted a customer service form on the ROH website, writing that she was in ‘tears of shock’ during the ballet scene, which she found to be ‘the worst kind of gratuitous’. She advises that ‘at the very least … the performance should come with a strong warning, as I have many friends I would love to take to the opera, who have been the victims of sexual violence, I would never forgive myself if I subjected them to what I saw on Friday’.Footnote 46 Kasper Holten responded to Woodward directly in an email, which she reproduced on her blog. He also wrote an open letter addressing Woodward and others who were upset, which was published on Norman Lebrecht's popular classical music blog, Slipped Disc. Holten defends the production for representing ‘the reality of warfare’, but he also apologises ‘for not issuing a strong and clear enough warning’.Footnote 47 He reflects that audience members ‘should be able to make an informed choice about what they want to see or not, and if an audience member does not want to be exposed to sexual violence, it should be their choice’.Footnote 48

Woodward focuses her argument on the risks that representations of rape pose to survivors of sexual violence. In her blog post, she cites an article reporting that approximately one in two women in Britain have been physically or sexually assaulted.Footnote 49 In his first response to Woodward's letter, Holten writes that given the opera's topic of war and oppression, ‘it is important that we do not only allow [Rossini's] opera to become harmless entertainment today’.Footnote 50 Holten seems to be using language of harm in a figurative way here – he wants audiences to be made uncomfortable so that they will think critically about this opera's politics. But Woodward is calling attention to real psychological and physiological harm when she talks about her fear for survivors of sexual assault who will attend this production. The phenomenon Woodward is referring to is a kind of retraumatisation in which post-traumatic stress reactions can be triggered or exacerbated by stressors that are not necessarily traumatic in and of themselves. These stressors can include reminders of the original traumatic experience like, in this example, a staged representation of a sexual assault. Potential symptoms are wide-ranging, including ‘posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, depressive symptoms, physical complaints, grief reactions, and/or general anxiety’.Footnote 51 Holten writes in his Slipped Disc letter that although the scene was meant to be upsetting, he had ‘no intention to disturb people in the way Catharine describes’.Footnote 52

Woodward's and Holten's different uses of language about harm in relation to viewing a representation of sexual violence amounts to a misunderstanding about the stakes at play. Holten seems initially reluctant to issue a specific warning about the sexual violence in Tell because he believes that the scene should be shocking and should make audience members uncomfortable, in service of the director's gritty commentary on the reality of war and war crimes. But Woodward is not advocating for herself in her discomfort, but for sexual violence survivors who may be living with PTSD. Her position essentially echoes a foundational idea of modern psychiatry, that ‘trauma is qualitatively different from stress and results in lasting biological change’.Footnote 53 When Woodward asks Holten to warn audiences about the explicit display of sexual violence in this production which is not present in the opera's written text, she is not worried about discomfort. She is aiming to give survivors of sexual violence the opportunity to make an informed decision about their capacity to engage with this production.

Woodward's exchange with Holten highlights the risks of putting sexual violence on stage, especially in an opera where even audience members already familiar with the written text would not expect it. But there are reasons to stage sexual violence that directors and producers must weigh against these risks. Holten's defence of Michieletto's staging hinges on the critical commentary about war that the production engages in. Essentially, he argues that it is important to include rape in this production because it is set in the midst of a war, and we know that during wartime women of the enemy group are frequently raped. The implication is that because rape exists in war in real life, it is necessarily appropriate to include scenes of rape in representations of war on stage. But I would argue that there is something more sophisticated at work in Michieletto's representation as well. Yes, the sexual assault serves the sense of realism in Michieletto's approach to the setting and functions in the plot to illustrate how bad the Austrian occupation is. But the ballet scene can also be read as a critique of the written text of Guillaume Tell and other war operas in general, which all too often glorify and romanticise war and the military. Many stagings feature a corps of dancers who perform a charming folk-inspired dance number, extraneous to the plot, in which the men happen to wear military costumes and the women wear peasant attire. By highlighting the darkness that is already in this story about resistance under a brutal oppressor, Michieletto challenges our tendency to see this opera as something primarily optimistic. His staging of the ballet holds an unflattering mirror up to the audience. He seems to ask, why are you so shocked to see a prisoner of war being abused, when you came to an opera about a violent and unjust military occupation? Michieletto's ballet foregrounds the spectacle of suffering and makes it impossible to ignore.

Woodward is ultimately un-swayed by Holten's defence of the rape scene in Tell. To Holten's point that it is important to highlight violence against women in war zones, she explains, ‘it feels like I am having it highlighted at me all the time, often in a way that serves just to make me feel more vulnerable’.Footnote 54 Woodward is pointing out here that the potential harm caused by exposure to depictions of sexual violence does not end with trauma survivors. There are the familiar fears that exposure to violent imagery desensitises spectators to real-world violence, but what Woodward is getting at here is something more akin to hyper-sensitisation. New understandings about what constitutes rape have made the prevalence of sexual violence in our culture increasingly visible in recent years. That visibility is positive insofar as it encourages changes in the ways we think about and legislate sexual violence, which has long been normalised or ignored. But for women who are socialised under the threat of sexual violence, this visibility may not always feel so progressive. Cahill argues that ‘the threat of rape is a formative moment in the construction of the distinctly feminine body, such that even bodies of women who have not been raped are likely to carry themselves in such a way as to express the truths and values of a rape culture’.Footnote 55 While the inclusion of rape in this Guillaume Tell acts as a critique of nationalist and misogynistic oppression, it does so by reinforcing gender roles ascribed by rape culture: the soldiers have all the power and there is nothing the Swiss woman can do to stop them. And within this representation of yet another nameless woman being senselessly abused there is the pornographic potential of the exposed body of the dancer, writhing with exertion and wet with prop champagne. Here is the tension present in so many operatic representations of sexual violence: staging sexual violence can capitalise on the popularity of beloved operas to deliver scathing cultural and political critiques of misogyny and rape culture, but it also risks desensitising audiences to sexual violence through overexposure, reinforcing harmful stereotypes, and retraumatising assault survivors in the theatre. An ethical approach to representing sexual assault on the opera stage involves the careful balancing of these risks and benefits. This equation will look different based on not only the contemporary cultural moment, but the context of the opera in question. Let us ask, does the sexual violence in these productions come from a reading of the opera itself, or is it imposed from outside? And in either case, what critical work is being done by the representation?

Excavating sexual violence from the canon

Critics of Regietheater are quick to dismiss productions that interpolate acts of violence or sexual content into familiar works with claims about the authorial intent of the composer (and, less often, the librettist). In general, I do not find arguments about authorial intent particularly useful for judging the efficacy or quality of Regietheater concepts. However, it can be particularly powerful and compelling when a director uses the tools of production and staging to illuminate or uncover elements of a familiar work that are often disregarded. Guillaume Tell and Turandot both thematise sexual violence already – albeit obliquely. Michieletto and Knabe are not so much inventing rape stories within these familiar classics as calling attention to the rape stories that were always there. Liane Curtis and Kassandra Hartford have theorised the dangers of obscuring sexual violence in the way operas are taught, and they encourage a pedagogical approach that foregrounds and names sexual violence for students.Footnote 56 Production is another important tool for drawing the sexual violence out of works and making it impossible to ignore.

In the third-act ballet in Guillaume Tell, the Austrian soldiers force the Swiss women to dance for them. But even outside of this scene, Tell's libretto alludes to other acts of sexual violence. Early in the opera's first act, the shepherd Leuthold explains that he killed one of the Austrian soldiers because that soldier had attempted to abduct his daughter. Given the context of a military occupation, this alone may be readily interpreted as intent to rape, but there is even more clarity in the libretto's source material. In Schiller's play it is not Leuthold but Baumgarten who kills an Austrian soldier, and it is in defence of his wife, not his daughter. Baumgarten explains that he did what any man would do: ‘I exercised my rights upon a man / Who would befoul my honor and my wife's’.Footnote 57 In the credits for the DVD of Michieletto's ROH Tell, the woman that is raped in the ballet scene is called ‘Leuthold's daughter’, so the inclusion of the rape scene is linked directly to the existing allusion to sexual violence in the first act of the opera. Michieletto capitalises on this undercurrent of sexual violence in a number of ways throughout his production in addition to the attempted gang rape in the ballet. In the written text, the opening scene depicts the bucolic bliss of the Swiss people who are happy at work while a fisherman sings a love song. Michieletto's production opens grimly: the fisherman is intoxicated and staggers through the assembled company as he sings, stopping at one point to roughly grope the breasts of a woman in the chorus. She resists and he leaves her alone, but there is little response from anyone else on stage. From the opera's first scene, we see that sexualised violence is not unusual here, and that the Swiss women do not occupy a social position of much respect, even in their own community. Later on, Mathilde, an Austrian woman in a relationship with one of the Swiss men, is threatened and harassed by both her lover and Governor Gessler. Michieletto avoids making sexual and gendered violence exclusively the problem of the enemy Austrians and shows that it is also pervasive within the ranks of the Swiss themselves. This is an interesting perspective for a wartime story. Michieletto's production offers some resistance to Tell's romantic narrative of the heroic Swiss people overcoming their oppression.Footnote 58 The heroes are not themselves immune from oppressive behaviour along gender lines.

The inclusion of representations of sexual violence serves the story Michieletto is telling about the harsh realities of war. He engages with the idea of sexual violence in a relatively sophisticated way by depicting smaller pervasive forms of gendered violence in addition to the shocking rape scene in the third act. But although the presence of the gang rape in the ballet may be justified by both the plot of the opera and the rest of the production, there is evidence that there were gratuitous elements in the scene as it was performed at the dress rehearsal. Holten reported that some small changes were made to the scene in light of the comments made by Catharine Woodward and others. He characterises the changes as ‘tweaks’ and insists that the scene ‘has not changed in its essence. It is the same duration and makes the same point that we find valid for the theatrical context’.Footnote 59 If we take Holten at his word, then Michieletto deemed the full nudity of the dancer and some of the more explicit gestures – such as Gessler simulating rape with his gun – to be non-essential to the drama. The choice to do without these elements is not only more sensitive to the risks of representing sexual violence on stage, but it also streamlines the staging of the ballet so that every action is necessary and in service of Michieletto's vision. With so little visible nudity and no simulation of sexual penetration on stage, this scene captures the fear and the humiliation that the soldiers achieve through this sexual violence, while side-stepping at least some of the pornographic potential of putting rape on stage.Footnote 60

Turandot's written text similarly features both allusions to sexual violence and acts that can be interpreted as sexually violent. Turandot's resistance to being married stems directly from fear of ending up like her ancestor, Princess Lo-u-Ling, who was ‘trascinata da un uomo, come te, come te, straniero, là nella notte atroce, dove si spense la sua fresca voce’ (‘dragged by a man like you, stranger, into the dreadful night where her sweet voice was silenced’). This is often read as meaning that Lo-u-Ling was raped as well as murdered by the usurper.Footnote 61 Later, when Calaf wants to kiss Turandot, she resists, saying, ‘dell'ava lo strazio non si rinnoverà’ (‘the agony of my ancestor will not be repeated’). The language of Turandot's protestations makes it clear that she perceives any kind of intimate contact with Calaf to be a dire threat to her safety, in light of what happened to Lo-u-Ling. Calaf talks about his desire for Turandot almost exclusively in terms of winning or conquering her. ‘Nessun dorma’ famously ends with his threefold repetition of ‘vincerò!’ And Calaf and Turandot's kiss in the third act of the opera is already an act of sexual violence. It is an intimate, romantic act that Turandot actively resists. It is clear from the text that Turandot understands this act as being commensurate with Lo-u-Ling's rape and murder. A production that treats this scene and the rest of the dénouement like a romance in which Turandot is radically transformed by Calaf's affections normalises the idea that women sometimes need to be forced into intimacy, that it is ultimately for their own good, and that they will be grateful in the end.

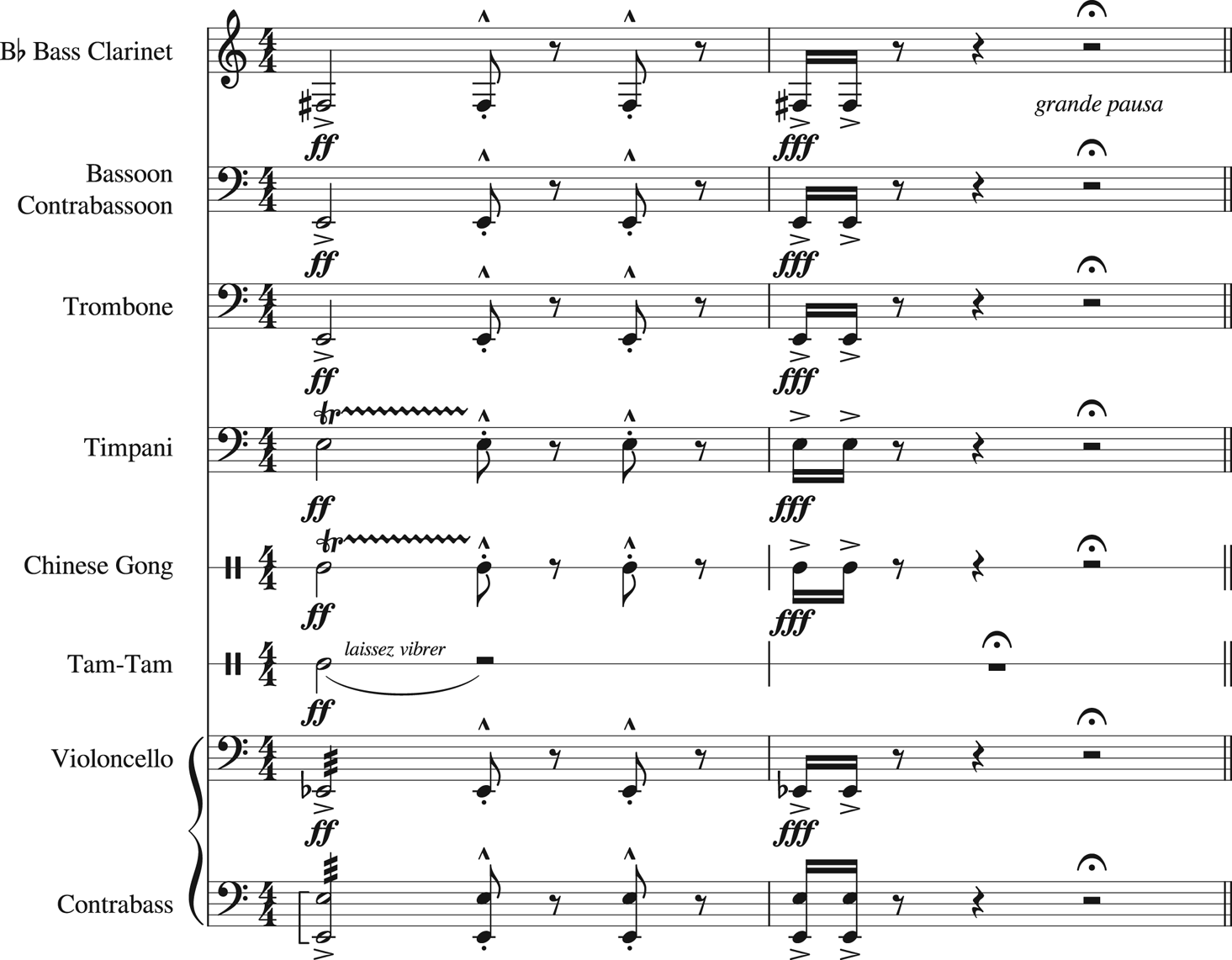

The brutal rape in Knabe's Turandot is supported by more than the character of the libretto. While Michieletto's Tell plays off the cheery dance music of the ballet to contrast the brutal stage action, Knabe's rape scene in Turandot is actually well supported by Alfano's music (Example 3). Roger Parker describes the musical realisation of this scene as ‘brief and violent to the point of brutality … Tristan-like dissonance piles on dissonance and then releases onto a sequence of rhythmically irregular, triple forte bangs on the drum, bassoons and trombones. If this is a representation of sex, then the act is a barbaric, messy business, overwhelmingly concerned with power.’Footnote 62 Knabe seems to hear this sequence of rhythmically irregular strikes at the moment of the kiss in essentially the same way that Parker does: in his production, these percussive strikes align with the sharp thrusts of Calaf's hips as he rapes Turandot. There is a long pause notated in the score at this moment, during which Knabe's Calaf stands, refastens his trousers, and leaves Turandot lying motionless on the bed. Parker's reading of the music of this scene, from its violence to its equation of sex and power, comes to life on Knabe's stage.

Example 3. Puccini/Alfano, Turandot, Act III scene 1, 10–11 bars after no. 38.

After the rape, the new cuts made to the score support the telling of a different kind of story about rape. In the written text, Turandot's initial responses to the event are exclusively negative. She says she is lost, conquered and disgraced. She is weeping. In this production, Calaf's ensuing commentary on the miracle of Turandot's first kiss and her first weeping remains intact.Footnote 63 But Turandot's response, narrating her trembling awakening to love, is gone. Instead, the next thing she says is that he has won his prize so now he can leave.Footnote 64 Losing just 70 bars of music eliminates all of Turandot's apologetics for Calaf's violence. There is nothing to soften the sense of her defeat. Her final proclamation, ‘il suo nome è Amor!’ (‘his name is Love!’), rings hollow, especially as she stands alone in the bedroom where we just saw her raped. The fact that the music of this production supports the critical dramatic project is no doubt one of the strengths of Knabe's and Soltesz's Turandot. While the alienation effect discussed above is a central aesthetic of Regietheater, some cooperation between music and drama can go a long way to making a conceptual production coherent.Footnote 65 I hope we might see more of this kind of collaboration between stage director and music director in service of interpretive projects in Regietheater productions in the future.

* * *

Two primary currents run through these four wartime opera productions featuring rape. First, rape is a metaphor for war: rape represents the domination and destruction of one group by another. Second, rape is an element of realism: because rape is common in real-world warfare, the inclusion of rape in operas about war makes them more realistic. The metaphorical weight of wartime rape has long been a useful tool in the theatre. It is not often feasible to show the larger-scale tactics of warfare on the stage; huge bloody battles typically resist live representation in this way. Wartime rape, though, is interpersonal in its scope while still representing the conflict at large. Theatre historian Jennifer Airey writes of the political resonance of rape narratives on England's Restoration stage: ‘Acts of rape in political tracts and stage plays … transform the female body into a symbol of the suffering nation, a physical representation of the horrific consequences of Catholic, Cavalier, Whig, Tory, Dutch, or Stuart rule.’Footnote 66 But while rape can certainly be an effective metaphor for war, the widespread use of rape as a way of representing other horrors is troubling. Airey goes on to warn about the potential dangers of transforming rape into ‘an artistic and allegorical symbol’, noting that these representations ‘transform that very real pain into social and political metaphors’.Footnote 67 Similarly, Lisa Fitzpatrick notices that contemporary theatre often stages rape in wartime as ‘a metaphor or as an allegory for forms of oppression other than gendered oppression’.Footnote 68 These theatrical uses of rape imagery, like the operatic uses throughout this article, depend on rape's status as a master trope for the violation of women by the patriarchy, but also of oppressed groups more generally. Literary theorist Sabine Sielke argues that such broad deployment of rape as a trope works to ‘diffuse the meaning of rape’.Footnote 69 Using rape to stand in for other harms centres a privileged position from which rape can be primarily a metaphor. The allegorical rapes in these productions demonstrate the baseness of the soldiers and lay plain the horrors of military occupation. But for some in the audience, especially those who have been or fear they may be sexually assaulted, this rape is not shocking as a symbol of another terrible thing, but as a terrible thing in itself. It is hard to see rape as standing for something else when the spectre of rape as rape is dominant in one's life. Catharine Woodward is getting at this problem when she writes that as a woman, she feels she is having the horrors of rape highlighted at her all the time.

The second current is well articulated in Kasper Holten's logic above, when he implies that the existence of rape in real-world warfare is justification enough to include rape scenes in operas set at wartime. Holten appears to be refuting Catharine Woodward's accusation that the rape was gratuitous by framing gratuitousness as a question of realism: it cannot be gratuitous if it reflects reality. The distinction between useful and gratuitous representations of sexual violence will not be consistent between different critics and spectators, but the fact of the existence of sexual violence at wartime does not itself settle the matter. There are situations in which the inclusion of sexual violence not explicitly called for in an opera's score can be ethically productive by prompting critical analysis of the opera or using an oft-performed opera as a way of advancing pertinent cultural conversations. But even from a position of accepting that adding violence to a work can be done ethically, the often sensationalised violence of the Regietheater aesthetic can feel like a bridge too far. There is undeniably a character of one-upmanship regarding the shock value of some of these productions; there are directors and producers that thrive on the controversy generated by outrageously lurid renditions of beloved operas. Sometimes these displays occur within an aesthetic of realism, as in Michieletto's Tell, but this is not always the case. In the performance of Guillaume Tell that I saw, after the changes had been made to the dress rehearsal version, the action on stage during the ballet was not, to my mind, gratuitous. I find Michieletto's and Holten's performance of the sexual violence inherent to the written text generally convincing. The production levels a devastating critique of the deeply misogynistic imperialist project of armies in occupied territories around the world. While not a particularly original concept for a contemporary take on a wartime opera, this production offers a strong political critique in the midst of a still legible interpretation of the familiar story.

All four productions considered here feature elements of rape as a metaphor and rape as realism in their depictions of sexual violence, but I am only convinced that the sexual violence is justified in two of them. The rapes in Bieito's Un ballo in maschera and Kratzer's La forza del destino both serve to criticise elements of modern warfare and soldiering, but I suspect that these directors could have accomplished their goals without recourse to such brutally explicit (Ballo) and perversely comic (Forza) scenes of sexual violence. Michieletto's Guillaume Tell and Knabe's Turandot are different cases, in large part because both Tell and Turandot contain underlying themes of sexual violence already. These operas support the directorial addition of the rape scenes, and the productions by Michieletto and Knabe offer compelling examinations of both the written texts of the operas themselves and the non-critical way in which directors and audiences often interact with them.

I asserted above that directors and producers must balance the risks of harm from depicting rape on stage with the potential benefits of dramatising social commentary. But in operas like Guillaume Tell and especially Turandot, which contain sexual violence just below the surface, there can be potential harms in ignoring the tacit allusions to rape as well. Englund refers to the strategy of pushing disturbing elements of opera into the spotlight to make them impossible to ignore a ‘hyperbolic gambit’, and he warns that ‘this mode of critique is a risk activity with high stakes: it may be potentially productive, but it is also liable to misfire in various ways’.Footnote 70 In the case of Michieletto's Guillaume Tell, I think we see such a misfiring in the dress rehearsal when, even by Holten's own account, the staging was more violent and sexually explicit than it needed to be to communicate the production's critique.

In Knabe's Turandot, there is certainly a risk that a sexual violence survivor may experience retraumatisation from witnessing Turandot's rape. But even in the absence of an explicit rape in a traditional production, this scene thematises sexual violence and reinforces harmful cultural ideas about consent. The rape in Knabe's Turandot is shocking, but it does more than just shock. Knabe calls attention to and criticises the virulent misogyny that is already foundational in this opera's text, and Soltesz's cuts to the score allow for a representation of this misogyny in which we do not have to hear the victim of forced intimacy explain that it was really for the best. To continue to perform an opera like Turandot in an ethical way demands that we engage with the dark and messy realities of the story it tells. In the house programme for Turandot, Knabe describes the opera as a male fantasy in which three men (Puccini and librettists Adami and Simoni) brutally destroy the only women in the opera: ‘Die eine bringt sich um und die andere wird missbraucht. Zynisch formuliert: Es lebe das Patriarchat’ (‘One [Liù] kills herself and the other [Turandot] is abused. To put it cynically: Long live the patriarchy’).Footnote 71 There is a rebellious quality to this kind of Regietheater that I find vital and exciting in the opera world; Turandot is an opera about sexual violence and the destruction of a powerful woman, and in this production Knabe and Soltesz refuse to pretend that it is not.