No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

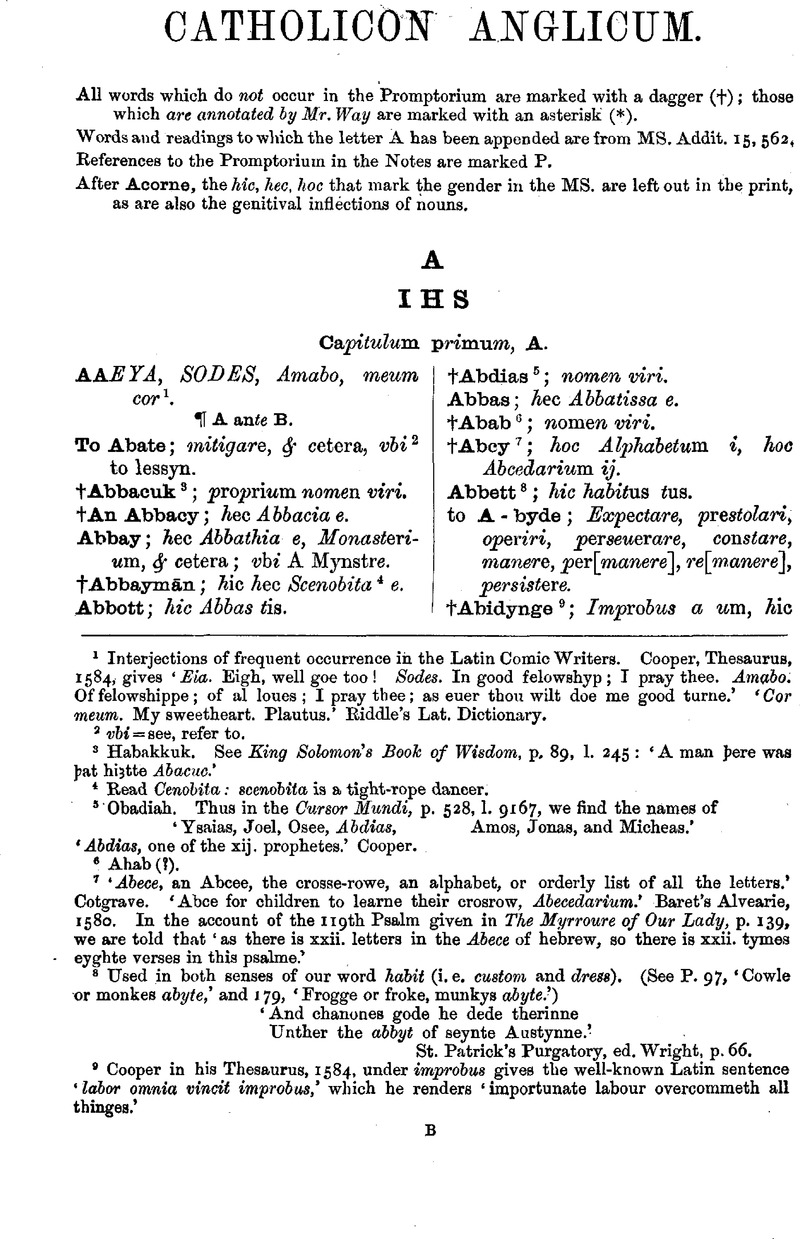

Catholicon Anglicum

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Catholicon Anglicum

- Information

- Camden New Series , Volume 30: Catholicon Anglicum an English-Latin Wordbook, Dated 1483 , December 1882 , pp. 1 - 428

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Historical Society 1882

References

page 1 note 1 Interjections of frequent occurrence in the Latin Comic Writers. Cooper, Thesaurus, 1584, gives ‘Eia. Eigh, well goe too! Sodes. In good felowshyp; I pray thee. Amabo. Of felowshippe; of al loues; I pray thee; as euer thou wilt doe me good turne.’ ‘Cor meum. My sweetheart. Plautus.’ Riddle's Lat. Dictionary.

page 1 note 2 vbi = see, refer to.

page 1 note 3 Habakkuk. See King Solomon's Book of Wisdom, p. 89Google Scholar, 1. 245: ‘A man pere was þat hiþtte Abacuc.’

page 1 note 1 Read Cenobita: scenobita is a tight-rope daneer.

page 1 note 5 Obadiah. Thus in the Cursor Mundi, p. 528Google Scholar, 1. 9167, we find the names of ‘Ysaias, Joel, Osee, Abdias, Amos, Jonas, and Micheas.’ ‘Abdias, one of the xij. prophetes.’ Cooper.

page 1 note 6 Ahab(?).

page 1 note 7 'sAbece, an Abcee, the crosse-rowe, an alphabet, or orderly list of all the letters.’ Cotgrave. ‘Abce for children to learne their crosrow, Abecedarium.’ Baret's Alvearie, 1580. In the account of the 119th Psalm given in The Myrroure of Our Lady, p. 139Google Scholar, we are told that ‘as there is xxii. letters in the Abece of hebrew, so there is xxii. tymes eyghte verses in this psalme.’

page 1 note 8 Used in both senses of our word habit (i.e. custom and dress). (See P. 97, ‘Cowle or monkes abyte,’ and 179, ‘Frogge or froke, munkys abyte.’)

'sAnd chanones gode he dede therinne

Unther the abbyt of seynte Austynne.’

St. Patrick's Purgatory, ed. Wright, , p. 66.Google Scholar

page 1 note 9 Cooper in his Thesaurus, 1584, under improbus gives the well-known Latin sentence ‘labor omnia vincit improbus,’ which he renders ‘importunate labour overcommeth all thinges.’

page 2 note 1 Chaucer, Prologue to Cant. Tales, 167, describes the monk as ‘A manly man, to ben aft abbot able.’ Cotgrave gives ‘Habile. Able, sufficient, fit for, handsome in, apt unto any thing he undertakes, or is put unto.’ In ‘The Lytylle Childrenes Lytil Boke,’ pr. in the Babees Boke, p. 267, 1. 44, we are told not to

'sspitte ouer the tabylle,

Ne therupon, for that is no thing abylle.’

In Lonelich's History of the Holy Grail, xxx. 382, a description is given of Solomon's sword, to which, we are told, his wife insisted on attaching hangings

'sso fowl … and so spytable,

That to so Ryal a thing ne weren not able.’

'sAptus. Habely.’ Medulla. ‘Tille oure soule be somwhat clensid from gret outewarde synnes and abiled to gostely werke.’ Hampole, , Prose Treatises, p. 20.Google Scholar

page 2 note 2 MS. eṛupere.

page 2 note 3 That is, the o in the oblique cases is long.

page 2 note 4 See also Serge-berer. The duties of the Accolite are thus defined in the Pontifical of Christopher Bainbridge, Archbishop of York, (1508–1514), edited for Surtees Society by Dr. Henderson, 1875, p. 11: ‘Acolythum oportet ceroferarium ferre, et luminaria ecclesiae accendere, vinum et aquam ad eucharistiam ministrare.’ See also the ordination of Acolytes, Maskell, Monumenta Ritualia, iii. 171. Thorpe, Ancient Laws, ii. 348, gives the following from the Canons of Ælfric: ‘xiv. Acolitus is gecweden seþe candele oððe tapor bẏrð to Godes þenungum þonne mann godspell rǽt. oððe þonne man halgað ![]() husl æt þam weofode.’ Wyclif speaks of ‘Onesimus the acolit.’ Prol. to Colossians.

husl æt þam weofode.’ Wyclif speaks of ‘Onesimus the acolit.’ Prol. to Colossians.

'sDe accolitis.

The ordre fer the accolyt hys

To bere tapres about wiзt riзtte,

Wanne me schel rede the gospel

Other offry to oure Dryte.’

Poems of William de Shoreham, p. 49.

page 3 note 1 The division of life into the two classes of active life or bodily service of God, and contemplative life or spiritual service, is common in mediæval theological writers. It ocours frequently in William of Nassyngton's ‘Mirror of Life,’ and in Hampole's Prose Treatises, see Mr. Perry's Preface, p. xi, and p. 19 of text; at p. 29 we are told that ‘Lya es als mekill at say as trauyliouse, and betakyns actyfe lyfe. Rachelle hyghte of begynnynge, þat es godd, and betakyns lyfe contemplatyfe.’ Langland in P. Plowman, B-Text, Passus vi. 251, says:—‘Contemplatyf lyf or actyf lyf cryst wolde men wrouзte:’ see also B. x. 230, A. xi. 80, C. xvi. 194, and Prof. Skeat's notes. In the ‘Reply of Frier Dan Topias,’ pr. in Political Poems, ed. Wright, ii. 63, we find:—

'sJack, in James pistles

al religioun is groundid,

Ffor there is made mencion

of two perfit lyres.

That actif and contemplatif

comounli ben callid

Ffulli figurid by Marie

and Martha hir sister,

By Peter and bi Joon,

by Rachel and by Lya (Leah).’

The distinction seems to have been founded upon the last verse of the ist chapter of the Epistle of St. James. Wiclif (Works, i. 384) says:—‘This is clepid actif liif, whanne men travailen for worldli goodis, and kepen hem in rightwisnesse.’

page 3 note 2 'sAimant, the Adamant, or Load-stone.’ Cotgrave. Cooper says, ‘Adamas. A diamonde, wherof there be diuers kindes, as in Plin. and other it appereth. It's rertues are, to resiste poison, and witchcrafte: to put away feare; to geue victory in contention: to healpe them that be lunatike or phrantike: I haue proued that a Diamonde layed by a nedell causeth that the loode stone can not draw the needel. No fire can hurte it, no violence breake it, onles it be moisted in the warme bludde of a goote.’

page 3 note 3 Tusser in his Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, p. 51Google Scholar, stanza 6, says:—

'sWhere ivy embraseth the tree very sore, Kill ivy, or tree else will addle ho more:’ and in ‘Richard of Dalton Dale’ we read:—‘I addle my ninepence every day.’ The Manip. Vocab. gives ‘to addil, demerere; to addle, lucrari, mereri.’ Icel. ödläsk = to win, gain. Cleasby's Icel. Dict. See note by Prof. Skeat in E. Dialect. Soo.'s edition of Ray's Glossary, p. xxi. ‘Hemm addlenn swa þe maste wa þatt aniз mann maзз addlenn.’ Ormulum, 16102. See also ibid. 6235, and Towneley Myst. p. 218.Google Scholar

page 3 note 4 We are told in Lyte's Dodoens, , p. 649Google Scholar, amongst other virtues of this plant, that ‘the ashes of the burned roote doo cure and heale scabbes and noughtie sores of the head, and doo restore agayne vnto the pilde head the heare fallen away being layde therevnto.’ ‘Aphrodille. The Affrodill, or Asfrodill flower.’ Cotgrave. Andrew Boorde in his Dyetary, ed. Furnivall, , p. 102Google Scholar, recommends for a Sawce-flewme face ‘Burre rotes and Affodyl rotes, of eyther iij. unces,’ &c.

page 4 note 1 Used here apparently in the sense of ‘to bridle, restrain,’ but in Early English to Affrayn was to question; A. S. offreinen, pt. t. offrœgn.

page 4 note 2 It is curious that the common meaning of this word (iterum) should not be given.

page 4 note 3 MS. octo, octogenti.

page 4 note 4 A sore either on the foot or hand. Palsgrave has ‘an agnayle upon one's too,’ and Baret, ‘an agnaile or little corn growing upon the toes, gemursa, pterigium.’ Minsheu describes it as a ‘sore betweene the finger and the nail., Agassin. A corne or agnele In the feet or toes. Frouelle. An agnell, pinne, or warnell in the toe.’ 1611. Cotgrave. ‘Agnayle: pterigium.’ Manip. Vocab. According to Wedgwood ‘the real origin is Ital. anguinaglia (Latin inguem), the groin, also a botch or blain in that place; Fr. angonailles. Botches, (pockie) bumps, or sores, Cotgrave.’ Halliwell, s. v. quotes from the Med. MS. Lincoln, leaf 300, a receipt ‘for agnayls one mans fete or womans.’ Lyte in his edition of Dodoens, 1578, p. 279, speaking of ‘Git, or Nigella,’ says:—‘The same stieped in olde wine, or stale pisse (as Plinie saith) causeth the Cornes and Agnayles to fall of from the feete, if they be first scarified and scotched rounde aboute.’ ‘Gemursa. A corn or lyke griefe vnder the little toe.’ Cooper.

page 4 note 5 This word occurs in H. More's Philosoph. Poems, p. 7:

'sThe glory of the court, their fashions

And brave agguize, with all their princely state.’

Spenser uses it as a verb: thus, Faery Queen, II. i. 21, we read, ‘to do her service well aguisd.’ See also stanza 31, and vi. 7. Indula is a contracted form of ‘inducula, a little garment.’ Cooper.

page 5 note 1 In the XI Pains of Hell, pr. in An Old Eng. Miscellany, p. 219Google Scholar, 1. 280, our Lord is represented as saying—‘Of aysel and gal зe зeuen me drenkyn;’ and in the Romaunt of the Rose, 1. 217, we read—

'sThat lad her life onely by brede, Kneden with eisell strong and egre.’

In the Forme of Cury, p. 56Google Scholar, is mentioned ‘Aysell other alegar.’ Roquefort gives ‘aisil, vinegar.’ In the Manip. Vocab. the name is spelt ‘Azel,’ and in the Reg. MS. 17, c. xvii, ‘aysyl.’ In Mire's Instructions to Parish Priests, p. 58Google Scholar, l. 1884 we find, ‘Loke þy wyn be not eysel.’ A. S. eisele, aisil.

page 5 note 2 Lyte in his edition of Dodoens, 1578, p. 746, says of Oak-Apples:—‘The Oke-Apples or greater galles, being broken in sonder, about the time of withering do forshewe the sequell of the yeare, as the expert husbandmen of Kent haue observed by the liuing thinges that are founde within them: as if they fmde an Ante, they iudge plentie of grayne: if a white worme lyke a gentill, morreyne of beast: if a spider, they presage pestilence, or some other lyke sicknesse to folowe amongst men. Whiche thing also the learned haue noted, for Matthiolus vpon Dioscorides saith, that before they be holed or pearsed they conteyne eyther a Flye, a Spider, or a Worme: if a Flye be founde it is a pronostication of warre to folowe: if a creeping worme, the scarcitie of victual: if a running Spider, the Pestilente sieknesse.’

page 5 note 3 'sDoloir. To grieve, sorrow: to ake, warch, paine, smart.’ Cotgrave. Baret points out the distinction in the spelling of the verb and noun: ‘Ake is the Verbe of this substantive Ache, Ch being turned into K.’ Cooper in his Thesaurus, 1584, preserves the same distinction. Thus he says—‘Dolor capitis, a headache: doletcaput, my head akes.’ The pt. t. appears as oke in Plowman, P., B. xvii. 194Google Scholar; in Lonelich, 's Hist. of the Holy GrailGoogle Scholar, ed. Furnivall, and in Robert of Gloucester, 68, 18. A. S. acan.

page 5 note 4 'sAlablastrites. Alabaster, founde especially aboute Thebes in Egipte.’ Cooper.

page 5 note 5 'sPronephas. Alas ffor velany.’ Medulla.

page 5 note 6 The following account of the origin of the name of Albania is given by Holinshed, Chronicles, i. leaf 396, ed. 1577:—‘The third and last part of the Island he [Brutus] allotted vnto Albanacte hys youngest sonne …‥ This latter parcel at the first toke the name of Albanactus, who called it Albania. But now a small portion onely of the Region (beyng vnder the regiment of a Duke) reteyneth the sayd denomination, the reast beyng called Scotlande, of certayne Scottes that came ouer from Ireland to inhabite jn those quarters. It is diuided from Lhoegres also by the Humber, so that Albania, as Brute left it, conteyned all the north part of the Island that is to be found beyond the aforesayd streame, vnto the point of Cathenesse.’ Cooper in his Thesaurus gives, ‘ Scotia, Scotlande: the part of Britannia from the ryuer of Tweede to Catanes.’

page 6 note 1 See P. Awbe. Cooper explains Poderis by ‘A longe garmente down to the feete, without plaite or wrinckle, whiche souldiours vsed in warre.’ Aphot is of course the Jewish Ephod, of which the same writer says there were ‘two sortes, one of white linnen, like an albe,’ &c. Lydgate tells us that the typical meaning of

'sThe large awbe, by record of scripture,

Ya rightwisnesse perpetualy to endure.’ MS. Hatton, 73, leaf 3.

See Ducange, s. v. Alba.

page 6 note 2 'sBalista. A crossebowe; a brake or greate engine, wherewith a stone or arrow is shotte. It may be vsed for a gunne.’ Cooper. See the Destruction of Troy, ll. 4743, 5707. In Barbour's Bruce, xvii. 236Google Scholar, Bruce is said to have had with him ‘Bot burgess and awblasteris.’ In the Romance of Sir Ferumbras we read how the Saracens

'sHure engyns þanne þay arayde,

& stones þar-wiþ þay caste.

And made a ful sterne brayde,

wiþ bowes & arbelaste’.

'sBalestro. To shotyn with alblast. Balista. An alblast; quoddam tormentum.’ Medulla.

page 6 note 3 'sAlburn-tree, the wild vine, viburnum.’ Wright's Prov. Dict. In the Harl. MS. 1002 we find ‘Awberne, viburnum.’ See note in P. s. v. Awbel, p. 17. Cotgrave gives ‘Aubourt, a kind of tree tearmed in Latine Alburnus, (it beares long yellow blossomes, which no Bee will touch),’ evidently the Laburnum.

page 6 note 4 Gower, , C. A., ii. 88Google Scholar has—

'sThilke elixir which men calle

Alconomy as is befalle

To hem that whilom were wise;’

and Langland, P. Plowman, B. x. 212, warns all who desire to Do-wel to beware of practising ‘Experimentз of alkenamye, þe poeple to deceyue.’ With the meaning of latten or white-metal the term is found in Andrew Boorde's ‘Introduction of Knowledge,’ ed. Furnivall, p. 163, where we are told that‘ in Denmark their mony is gold and alkemy and bras In alkemy and bras they haue Dansk whyten.’ Jamieson gives ‘Alcomye s. Latten, a kind of mixed metal, still used for spoons.’ ‘Ellixir. Matere off alcamyne.’ Medulla.

page 6 note 5 Cooper in his Thesaurus, 1584, gives ‘Silicernium. A certayne puddynge eaten onely at funeralles. Some take it for a feast made at a funerall. In Terence, an olde creeple at the pittes brincke, that is ready to have such a dinner made for him.’ Baret too has ‘an old creple at the pittes brincke, silicernium.’ and again, ‘verie old, at the pits brinke, at death's doore, decrepitus, silicernium.’

page 6 note 6 'sZyme. Leauen.’ Cooper. The reference evidently is to 1 Corinthians, v. 7, 8.

page 6 note 7 Properly only the first seven Books of the Old Testament.

page 7 note 1 'sAlgorisme, m. The Art, or Use of Cyphers, or of nnmbring by Cyphers: Arithmetick, or a curious kinde thereof.’ Cotgrave. In Richard the Redeles, iv. 53Google Scholar, we read—

'sThan satte summe as siphre doth in awgrym,

That noteth a place, and no thing availith.’

Chaucer, describing the chamber of the clerk ‘hende Nicholas,’ mentions amongst its contents— ‘His Almageste, and bookes grete and small,

His Astrelabie longynge for his art,

His Augrym stones layen faire a-part

On shelues couched at his beddes head.’ Millers Tale, 3208.

Gower, , C. A., iii. 89Google Scholar says—

'sWhan that the wise man acompteth

Aftir the formal proprete

Of algorismes a be ce.’

In the Ancren Riwle, p. 214, the covetous man is described as the Devil's ash-gatherer, who rakes and pokes about in the ashes and ‘makeð þerinne figures of augrim ase þeos rikenares doð þat habbeð mochel uorto rikenen.’

page 7 note 2 'sAmbulatio. A walkinge place; a galery; an alley.’ Cooper. ‘Allée, f. An alley, gallery, walke, walking place, path or passage.’ Cotgrave.

page 7 note 3 'sWith ostes of alynes fulle horrebille to schewe.’

Morte Arthure, 461.Google Scholar

'sAn alyane, alienus, extraneus.’ Manip. Vocab. ‘Alieno. To alienate: to put away: to sliene or alter possession.’ Cooper.

page 7 note 4 In the Paston Letters, i. 144, are mentioned ‘Lord Moleyns, and Alianore, his wyff.’

page 7 note 5 MS. missam; corrected from A.

page 7 note 6 Compare ‘Broder by the moder syde onely (alonly by moder P.)’ in P. p. 54. In the Gesta Romanorum, p. 49Google Scholar, Agape, the King of France, having asked Cordelia, Lear's youngest daughter, in marriage, her father replies that, having divided his kingdom between his other two daughters, he has nothing to give her. ‘When Agape herde this answere, he sente agayne to Leyre, and seide, he asked no thinge with here, but alonly here bodie and here clothing.’ See also the Lay-Folks Mass-Book, B. 210.

page 8 note 1 See Wedgwood, Etymol. Dict. s. v. Aumbry, and Parker's Glossary of Gothic Architecture. Dame Eliz. Browne in her Will, Paston Letters, iii. 465, bequeaths ‘vij grete cofers, v chestis, ij almaryes like a chayer, and a blak cofer bounden with iron.’ ‘An Ambry, or like place where any thing is kept. It seemeth to be deriued of this Frenche word Aumosniere, which is a little purse, wherein was put single money for the poore, and at length was vsed for any hutch or close place to keepe meate left after meales, what at the beginning of Christianize was euer distributed among the poore people, and we for shortnesse of speache doe call it an Ambry; repositorium, serinium.’ Baret. Cooper renders Scrinium by ‘A coffer or other lyke place wherein iewels or secreate thynges are kept, as euidences, &c. Scriniolum, a basket or forcet: a gardiuiance.’

page 8 note 2 MS. alnetam; corrected by A. Alnus is properly an elder-tree, and there is no such word as ulnus. Danish olm, an elm.

page 8 note 3 Hampole, Pricke of Conscience, 3609, amongst the four kinds of help which will assist souls in purgatory, mentions ‘Almus þat men to the pure gyves.’ And again, I. 3660, he speaks of the benefit of ‘help of prayer and almusdede.’ See also the Lay-Folks Mass-Book, p. 157Google Scholar. A. S. œlmesse, œlmes.

page 8 note 4 Harrison, in his Description of England, ii. 67Google Scholar, mentions amongst the minerals of England, ‘the finest alume …. of no lesse force against fire, if it were used in our parietings than that of Lipara, which onlie was in use somtime amongst the Asians & Romans, & wherof Sylla had such triall that when he meant to haue burned a tower of wood erected by Archelaus the lieutenant of Mithridates he could by no means set it on fire in a long time, bicause it was washed ouer with alume, as were also the gates of the temple of Jerusalem with like effect, and perceiued when Titus commanded fire to be put vnto the same.’

page 8 note 5 'sEousque. In alsmekyl.’ Medulla.

page 8 note 6 'sAn ambling horse, hacquenée.’ Palsgrave. Baret says, ‘Amble, a word derived of ambulo: an ambling horse, tolutarius, gradarius equus: to amble, tolutim incedere.’ In Pecock's Repressor, Rolls Series, p. 525, we have the form ‘Ambuler.’ ‘An ambling horse, gelding, or mare; Haquenée, Cheval qui va les ambles, ou l'amble; hobin.’ Sherwood. ‘Gradarii equi. Aumblyng horses.’ Cooper. In the following quotation we have amblere meaning a trot: ‘Duc Oliver him rideþ out of þat plas;

in a softe amblere,

Compare also,

’His steede was al dappel, gray,

It gooth an ambel in the way

Ne made he non oþer pas;

til þey wern met y-fere.‘

Sir Ferumbras, l. 344.Google Scholar

Ful softely and rounde

In londe.’

Rime of Sir Thopas, 2074.Google Scholar

page 9 note 1 In the Romance of Sir Ferumbras, Charlemagne orders Alorys to go down on his knees to Duke Rayner, ‘and his amendes make,’ i. e. make an apology to him. Alorys accordingly, we are told,

'sþe amendes a profrede him for to make

At heз and low what he wold take,

And so thay acorded ther.’ l. 2112.

See also P. Plowman, B. iv. 88.

page 9 note 2 MS. correptor.

page 9 note 3 'sUpon his heed the amyte first he leith,

Which is a thing, a token and figure

Outwardly shewing and grounded in the feith.’

Lydgate, MS. Hatton 73, leaf 3.

Ducange gives ‘Amictus. Primum ex sex indumentis episcopo et presbyteris communibus (sunt autem ilia amictus, alba, cingulum, stola, manipulus, et planeta, ut est apud Innocent III. P. P. De Myster. Missœ); amict.’ Cotgrave has ‘Amict. An Amict, or Amice; part of a massing priest's habit.’ In Old Eng. Homilies, ii. 163, it is called heued-line, i.e. head-linen.

page 9 note 4 See P. Onde. In Sir Ferumbras, p. 74Google Scholar, 1. 2237, we find ‘So harde leid he far on is onde;’ that is, he blew so hard on the brand; and in Barbour's Bruce, xi. 615Google Scholar, we are told that ‘Sic ane stew rais owth thame then

Of aynding, bath of hors and men.’

See also ll. iv. 199, x. 610. Ayndless, out of breath, breathless, occurs in x. 609. In the Cursor Mundi, p. 38Google Scholar, the author, after telling us that Adam was made of the four elements, says, l. 539:—

'sþe ouer fir gis man his sight,

þat ouer air of hering might;

þis vnder wynd him gis his aand,

þe erth, þe tast, to fele and faand.’

See also p. 212, where, amongst the signs of approaching death, we are told that the teeth begin to rot, ‘þe aand at stinc’ l. 3574. ‘Myn and is short, I want wynde.’ Townley Myst. p. 154Google Scholar. See also R. C. de Lion, 4843, Ywaine & Gawain, 3554. ‘To Aynd, Ainde, Eand. To draw in and throw out the air by the lungs.’ Jamieson. Icel. önd, ondi, breath; cf. Lat. anima. ‘Aspiro: To ondyn.’ Medulla.

page 9 note 5 In Religious Pieces in Prose and Verse from the Thornton MS., p. 13, l. 22, we are told that fornication is ‘a fleschle synne betwene an anelepy man and an anelepy woman;’ and in the Cambridge University Library MS. Ff. V. 48, leaf 86, we read—

'sWele more synne it is

Then with an analepe, i-wis.’

To synne with a weddid wife,

In Havelok, l. 2106, we have—

'sHe stod, and totede in at a bord, Ner he spak anilepi word,’

where the word has its original meaning of one, a single; and also in the following:—

'sA, quod the vox, ich wille the telle, On alpi word ich lie nelle.’ Reliq. Antiq. ii. 275Google Scholar. A. S. anelepiз, single, sole. ‘Hi true in God, fader halmichttende …‥ and in Thesu Krist, is ane lepi sone hure laverd.’ Creed, MS. Cott. Cleop. B. vi. Y 201b. ab. 1250. Reliq. Antiq. i. 22Google Scholar. Wyclif has ‘an oonlypi sone of his modir.’ Luke vii. 12. ‘þer beo an alpi holh þat an mon mei crepan in.’ O. B. Homilies, i. 23Google Scholar. See also Laзamon, ii.92, iii. 264, Ayenbite, p. 21Google Scholar, Ancren Riwle, pp. 116, 296Google Scholar, &c.

page 10 note 1 See note to Antiphonare.

page 10 note 2 The following is from Ducange:—‘Dindimum vel potius Dindymum, Mysterium. Templum. Vita S. Friderici Episc. Tom. 4, Julij, pag. 461: Ineptas, fabulas devitans, seniores non increpans, minores non contemnens, habens fidei Dindimum in conscientia bona. Allusio est ad haeo Apostoli verba 1 Timoth. 3.8: “Habentes mysterium fidei in conscientia bona. Angelomus Praefat. in Genesim apud Bern. Pez. tom. i. anecdot. col. 46:

“Hic Patriarcharum clarissima gesta leguntur,

Mystica quae nimium gravidis typicisque figuris

Signantur Christi nostraeque et dona salutis.

Hic sacra nam sacrae cernuntur Dyndima legis

Atque evangelica salpinx typica intonat orbi.

Papias: “Dindyma, mons est Phrygiae, sacra mysteria, pluraliter declinatur. Notus est mons Phrygiae Cibelae sacer Dindyma nuncupatus; unde Virgilius. “O vere Phrygiae, neque enim Phryges, ite per alta Dindyma. ’ See also Sete of Angellis.

page 10 note 3 The word anger or angre in Early English did not bear the meaning of our anger, but rather meant care, pain, or trouble. Thus in P. Plowman, B. xii. 11, we find the warning:

'sAmende þe while þow hast ben warned ofte,

With poustees of pestilences, with pouerte and with angres,’

and in the Pricke of Conscience, 6039, we are told of the apostles, that for the love of Christ, ‘þay þoled angre and wa,’ O. Icel. angr.

page 10 note 4 MS. vilose.

page 10 note 5 MS. vilosus.

page 10 note 6 In Sir Degrevant (Thornton Romances, ed. Halliwell), p. 179Google Scholar, l. 63, we read,

'sAs an anker in a stone He lyved evere trewe.’

The same expression occurs in the Metrical Life of St. Alexius, p. 39, l. 420. ‘As aneres and heremites þat holden hem in here selles.’ P. Plowman, B. Prol. 38. The term is applied to a nun in Reliq. Antiq. ii. I. Palsgrave has ‘Ancre, a religious man: anchres, a religious woman.’ A.S. ancor. ‘Hec anacorita, a ankrys.’ Wright's Vol. of Vocab. p. 216.

page 10 note 7 'sHis cote …. ennurned vpon veluet vertuus stoneз.’ Sir Gawaine, 2026. Wyclif has the subst. enournyng in Esther ii. 9 to render the V. mundum; and again he speaks of ‘Onychen stoonus and gemmes to anourn ephoth.’ Exodus xxv. 7. ‘Thanne alle the virgynis rysen vp, and anourneden her laumpis.’ Matth. xxv. 7. ‘Whan a woman is qnourned with rich apparayle it setteth out her beauty double as much as it is.’ Palsgrave. ‘I am tormentide with this blew fyre on my hede, for my lecherouse anourement of myne heere.’ Gesta Roman, p. 384Google Scholar. ‘With gude ryghte thay anourene the for thaire fairenes.’

Lincoln MS. p. 199. In Lonelich's History of the Holy Grail, xxxi. 151Google Scholar, we read

'sзit was that schipe in other degre

Anoured with divers Jowellis certeinle;’

and Rauf Coilзear, when he enters the Hall of Charlemagne, exclaims

'sHeir is Ryaltie …. aneuch for the nanis,

With all nobilnes anournit, and that is na nay.’ I. 690.

See also the Lay-Folks Mass-Book, ed. Canon Simmons, Bidding Prayers, p. 65, I. 4, p. 71, I. 20, &c, Allit. Poems, B. 1290, and Cursor Mundi, l. 3922. ‘Anorne, to adorn.’ Jamieson. O. Fr. aorner, aourner; Latin adornare. The form anorme is used by Qustrles, Shepherd's Eclogues, 3, and enourmyd in the Babees Book, p. 1.

page 11 note 1 Antiphoner, an anthem-book, so called from the alternate repetitions and responses.

'sHe Alma Redemptoris herde singe,

As children lerned hir antiphoner.’

Chaucer, Prioresses Tale, 1708.

In the contents of the Chapel of Sir J. Fastolf at Caistor, 1459, are entered ‘ij antyfeners.’ Paston Letters, i. 489. See also Antym, below, and Anfenere.

page 11 note 2 In the Myrroure of Our Lady, p. 94Google Scholar, Anthem is stated to be equivalent to both antehymnus and ἀντίφωνα. ‘Antem ys as moche to say as a wownynge before, for yt ys begonne before the Psalmes. yt is as moche to saye as a sownynge ayenste …… Antempnes betoken chante, The Antempne ys begonne before the Psalme, and the psalme ys tuned after the antempne: tokenynge that there may no dede be good, but yf yt be begone of charite. and rewled by chnrite in the doynge, &c.

page 11 note 3 An Apostata was one who quitted his order after he had completed his year of noviciate. This is very clearly shown by the following statement of a novice:—

'sOut of the ordre thof I be gone.

Apostata ne am I none,

Of twelve monethes me wanted one,

And odde dayes nyen or ten.’

Monumenta Franciscana, p. 606.

'sApostata, a rebell or renegate; he that forsaketh his religion.’ Cooper. The plural form Apostataas is used by Wyclif (Works, ed. Arnold, iii. 368). See Prof. Skeat's note to Piers Plowman, C-Text, Passus ii. 99. ‘Julian the Apostata’ is mentioned in Harrison's Description of England, 1587, p. 25. ‘Apostat, an Apostata.’ Cotgrave. In the Paston Letters, iii. 243, in a letter or memorandum from Will. Paston, we read: ‘In this case the prest that troubleth my moder is but a simple felowe, and he is apostata, for he was sometyme a White Frere.’ See also i. 19, i. 26. From the latter passage it would appear that an apostata could not sue in an English Court of Law.

page 11 note 4 'sApostume, rumentum.’ Manip. Vocab. ‘Aposthume, or brasting out, rumentum.’ Huloet. ‘A medicine or salve that maketh an aposteme, or draweth a swelling to matter.’ Nomenclator, 1585.

page 11 note 5 'sPrunelle, the balle or apple of the eye.’ Cotgrave. ‘Als appel of eghe зheme þou me.’ E. E. Psalter, Ps. xvi. 8.Google Scholar

page 11 note 6 Applegarthe, appleyard, pomarium.’ Manip. Vocab. A. S. зeard, O. H. Ger. gart, Lat. hortum.

page 11 note 7 Chaucer, Miller's Tale, says of the Carpenter's wife that—

'sHir mouth was sweete as bragat is or meth,

Or hoord of apples, layd in hay or heth.’

l.3261.

page 12 note 1 Hampole, Pricke of Conscience, 9346, says, that in addition to the general joys of heaven each man will have

'sHis awen ioyes, les and mare,

Þat til hym-self sal be appropried þare.’

'sÞes ypocritis þat han rentes & worldly lordischipes & parische chirchis approprid to hem.’ Wyclif, English Works, ed. Matthew, p. 190; see also pp. 42, 125, &c. See also to make Awne, below.

page 12 note 2 See Are-lumes in Glossarium Northymbricum, and Ray's Gloss, of North Country Words. ‘Primigenia. The title of the ealdest childe in inheritance.’ Cooper.

page 12 note 3 O. Fr. areisnier, aragnier, to interrogate, whence our word arraign. See Kyng Alysaundre, 6751; Ywaine and Gawayne, 1094; Rom. of the Rose, 6220. ‘Arraissoner. To reason, confer, talke, discourse, &c.’ Cotgrave. Hampole tells us how at the Day of Judgment ‘Of alle þir thynges men sal aresoned be.’ P. of Conscience, 5997. And again, l. 2460, that each man shall

'sbe aresoned, als right es

Of alle his mysdedys mare and les.’

page 12 note 4 This word occurs in the Destruction of Troy, 1. 2540, and the verb arghe = to wax timid, to be afraid (from A. S. eargian) at ll. 1976, 3121, and (with the active meaning) 5148; and Allit. Poems, B. 572:

'sþe anger of his ire þat arзed monye.’

See also Plowman, P., C. iv. 237Google Scholar; Ayenbite, p. 31Google Scholar; O. E. Miscell., p. 117Google Scholar, &c.

'sþienne arзed Abraham, & alle his mod chaunged.’ Allit. Poems, B. 713.Google Scholar

'sHe ealde boþe arwe men and kene,

Knithes and serganз swiþe sleie.’ Havelok, l. 2115.

See also Sir Perceval, l. 69Google Scholar, where we are told that the death of one knight ‘Arghede alle that ware thare.’ ‘Arghness, reluctance. To Argh. To hesitate.’ Jamieson. A. S. eargh, earh; O. Icel. argr.

page 13 note 1 'sIn Chaucer, Knightes Tale, 1871, we have—

'sIt nas aretted him no vyleinye,

Ther may no man olepe it no cowardye.’

According to Cowell a person is aretted, ‘that is covenanted before a judge, and charged with a crime.’ In an Antiphon given for the ‘Twesday Seruyce,’ in The Myrroure of Our Lady, p. 203Google Scholar, we read:—‘Omnem potestatem. O mekest of maydens, we arecte to thy hye sonne, al power, and all vertew, whiche settyth vp kynges, &c.’ Low Lat. arrationare. See Sir Ferumbras, 5174; Hampole, , Prose Treatises, p. 31Google Scholar, &c.

page 13 note 2 'sArrierages is a french woorde, and signifieth money behinde yet vnpayde, reliqua.’ Baret. Arrirages occurs in Liber Albus, p. 427, and frequently in the Paston Letters.

'sI drede many in arerages mon falle

And til perpetuele prison gang.’ Hampole, P. of Conscience, 5913.

'sArrierage. An arrerage: the rest, or the remainder of a paiment: that which was unpaid or behind.’ Cotgrave. ‘God …‥ that wolle the arerages for-зeve.’ Shoreham, , p. 96.Google Scholar

page 13 note 3 Compare P. Assenel.

page 13 note 4 In John Russell's ‘Boke of Nurture,’ pr. in the Babees Booke, ed. Furnivall, p. 65, we find amongst the duties of the Chamberlain—

'sSe þe privehouse for esement be fayre, soote and clene ….

Looke þer be blanket, cotyn, or lynyn, to wipe þe nefur ende;’

on which Mr. Furnivall remarks,—‘From a passage in William of Malmesbury's Autograph, De Gestis Pontificum Anglorum, it would seem that water was the earlier cleanser.’ ‘An Arse-wispe, penicillum, anitergium.’ Withals.

page 13 note 5 In the story of the Enchanted Garden, Gesta Romanorum, p. 118Google Scholar, the hero having passed safely through all the dangers, the Emperor, we are told, ‘when he sawe him, he yaf to him his dowter to wyfe, be-cause that he had so wysely ascapid the peril of the gardin.’ See also Plowman, P., C. iv. 61.Google Scholar

page 13 note 6 Amongst the kinds of help which may be rendered to souls in purgatory, Hampole mentions ‘assethe makyng.’ P. of Conscience, 3610, and again, 1.3747, he says—

'sA man may here with his hande

Make asethe for another lyfannde.’

In the Romaunt of the Rose we find asethe, the original French being asses: other forms found are assyth, syth, sithe. Jamieson has ‘to assyth, syith, or sithe, to compensate; assyth, syth, assythment, compensation.’ ‘Icel. seðja, to satiate; Gothic saths, full; which accounts for the th. And this th, by Grimm's law, answers to the t in Latin satis, and shews that aseth is not derived from satis, but cognate with it. From the Low German root sath- we get the Mid. Eng. aseth, and from the cognate Latin root sat- we have the French assez.’ Prof. Skeat, note on P. Plowman, xx. 303. In Dan John Gaytryge's Sermon, pr. in Belig. Pieces in Prose and Verse, from the Thornton MS. p. 6, 1. 22, we are told that if we break the tenth commandment, ‘we may noghte be assoylede of þe trespase bot if we make assethe in þat þat we may to þam þat we harmede;’ and again, leaf 179, ‘It was likyng to зow, Fadire, for to sende me into this werlde that I sulde make asethe for mans trespas that he did to us.’ See also Gesta Romanorum, p. 84.Google Scholar

page 14 note 1 In Havelok, l. 2840, we read that Godrich—

'sHwan þe dom was demd and sayd

Sket was .… on þe asse leyd,

And led vn-til þat ilke grene.

And bread til asken al bidene;’

and in An Old Eng. Miscell., p. 78Google Scholar, I. 203, we are told that when the body is laid in the earth, worms shall find it and ‘to axe heo hyne gryndeþ.’

'sThynk man, he says, askes ertow now,

And into askes agayn turn saltow.’

MS. Cotton; Galba, E. ix. leaf 75.

'sMoyses askes vp-nam And warp es vt til heuene-ward.’

Genesis & Exodus, 3824.

See also Laзamon, 25989; Ormulum, 1001; Sir Gawayne, 2, &c. Lyte in his edition of Dodoens, 1577, p. 271, tells us that Dill ‘made into axsen doth restrayne, close vp and heale moyste vlcers.’ See also P. Plowman, C. iv. 125, ‘blewe askes.’ A. S. asce, œsce, axe. O. Icel. aska.

page 14 note 2 'sAn asseherd, asinarius.’ Manip. Vocab. ‘Hic asinarius, a nas-herd.’ Wright's Vol. of Vocab. p. 213.

page 14 note 3 MS. kynge. ‘Onocentanrus, a beaste halfe a man and halfe an asse.’ Cooper.

page 14 note 4 See Glossary to Liber Custumarum, ed. Riley, s. v. Assise. ‘Assises or sessions, conuentus iuridici; dayes of assise, or pleadable dayes, in which iudges did sit, as in the terme, fasti dies.’ Baret.

page 15 note 1 'sThis sodeyn cas this man astonied so,

That reed he wex, abayst, and al quaking

He stood.’ Chaucer, Clerkes Tale, 316.Google Scholar

'sEstonner. To astonish, amaze, daunt, appall; make agast; also to stonnie, benumme, or dull the sences of.’ Cotgrave. ‘Attono. To make astonied, amased, or abashed. Attonitus. He that is benummed, or hath loste the sense, and mouyng of his members or limmes.’ Cooper. Probably connected with the root which is seen in A. 8. stunian, to stun.

page 15 note 2 'sHis almagest, and bookes gret and smale,

His astrylabe longyng for his arte,

His augrym stoones, leyen faire apart

On schelues couched at his beddes heed.’ Cant. Tales, 3208.

See a woodcut of one in Prof. Skeat's ed. of Chaucer's Astrolabe.

page 15 note 3 MS. avande; corrected from A.

page 15 note 4 A word which occurs very frequently in the Gesta Romanorum: thus p. 48Google Scholar, in the version of the tale of Lear and his daughters we read that when his eldest daughter declared that she loved him, ‘more þan I do my selfe,’ “Þerfore, quod he, þou shalt be hily avaunsed; and he mariede her to a riche and myghti kyng.’ So also p. 122, the Emperor makes a proclamation that whoever can outstrip his daughter in running ‘shulde wedde hir, and be hiliche avauncyd.’ See also Barbour's Bruce, xv. 522Google Scholar. ‘Avancer, to advance, prefer, promote.’ Cotgrave.

page 15 note 5 A word of frequent occurrence in the old Romances In the sense of ‘consider, reflect, inform, teach.’ Thus in the ‘Pilgrymage of the Lyf of the Manhode,’ Roxburgh Club, ed. Wright, p. 4, we find ‘I avisede me,’ i. e. I reflected, considered. So in Chaucer, Clerkes Tale, 238Google Scholar: ‘Vpon hir chere he wolde him ofte auyse.’ See Barbour, 's Bruce, ii. 297, vi. 271Google Scholar, &c. ‘Aviser. To marke.heed, see, looke to. attend unto, regard with circumspeotion, to consider, advise of, take advice on; to thinke, imagine, judge; also to advise, counsell, warne, tell, informe, doe to wit, give to understand.’ Cotgrave.

page 15 note 6 'sAmbra. Amber gryse: hotte in the second degree, and drie in the firste.’ Cooper. ‘Ambre, m. Amber.’ Cotgrave. See Destruction of Troy, ll. 1666 and 6203. Harrison, Descript. of England, ed. 1580, p. 43Google Scholar, says that in the Islands off the west of Scotland ‘is greate plentie of Amber,’ which he concludes to be a kind of ‘geat’ (jet), and ‘producted by the working of the sea upon those coasts.’

page 15 note 7 'sAdulter. That hath committed auoutrye with one. Adultero. To committe auoutery. Adulterium. Aduouterie.’ Cooper. See Gesta Romanorum, pp. 12, 14Google Scholar. &c.

page 16 note 1 In the Will of Margaret Paston, dated 1504, we find, ‘Item to the said William Lumner, my son, ij grete rosting awndernes, iij shetes, ij brass pots with all the brewing vessels.’ Paston Letters, iii. 470. O. Fr. andier.

page 16 note 2 'sFlaxen wheate hath a yelow eare, and bare without anys, Polard whete hath no anis. White whete hath anys. Red wheate hath a flat eare ful of anis. English wheate hath few anys or none.’ Fitzherbert's Husbandry, leaf 20. ‘Arista. The beard of corne; sometimes eare; sometime wheate.’ Cooper. ‘Awns, sb. pl. aristæ, the beards of wheat; or barley. In Essex they pronounce it ails. See ails in South-Country Words, E. Dial. Soc. Gloss. B. 16.’ Prof. Skeat in his ed. of Ray's Gloss, of N. Country Words, 1691. Turner tells us that ‘ye barley eare and the darnele eare are not like, for the one is without aunes and the other hath longe aunes.’ Herbal, pt. ii. If. 17. Best tells us that we ‘may knowe when barley is ripe, for then the eares will crooke eaven downe, and the awnes stand, out stiff and wide asunder.’ Farming, &c. Book, p. 53.

page 16 note 3 MS. doxtghter.

page 16 note 4 See the Lay-Folks Mass-Book, pp. 165, 168Google Scholar, and B. P. p. 71, l. 20.

page 16 note 5 Ray in his Gloss, of North Country Words, gives ‘Axeltooth, dens molaris; Icel. jaxl:’ and in Capt. Harland's Gloss, of Swaledale, E. D.S. is given ‘Assle-tuth, a double tooth.’ Still in use in the North; see Jamieson, s. v. Asil-tooth. Compare also Wang tothe.

page 16 note 6 'sAxis. An extree. Axis. An axyltre.’ Cooper. A. S. eaxe.

page 16 note 7 In the Paston Letters, iii. 426, we read—‘I was falle seek with an axez.’ It also occurs in The King's Quhair, ed. Chalmers, p. 54:

'sBut tho begun mine axis and torment.’

with the note—‘ Axis is still used by the country people, in Scotland, for the ague.’ Skelton, Works, i. 25, speaks of

'sAllectuary arrectyd to redres

These feverous axys.’

See Calde of the axes, below. ‘Axis, Acksys, aches, pains.’ Jamieson. ‘I shake of the axes. Je tremble des fieures.’ Palsgrave. ‘The dwellers of hit [Ireland] be not vexede with the axes excepte the scharpe axes [incolæ nulla febris specie vexantur, excepta acuta, et hoc perraro]. Trevisa, i. 333. See Allit. Poems, C. 325Google Scholar, ‘þacces of anguych,’ curiously explained in the glossary as blows, from A. S. þaccian.

page 17 note 1 Cotgrave s. v. Fol has ‘give the foole his bable, or what's a foole without his bable.’ ‘A bable or trifle, niquet.’ ibid. ‘A bable pegma;’ Manip. Voeab. ‘He schalle neuer y-thryve, þerfore take to hym a babulle.’ John Russell's Boke of Nurture, in the Babees Boke, ed. Furnivall, p. 1, 1. 12. In the Ancren Riwle, p. 388, when a certain king made efforts to gain the love of a lady, he ‘sende hir beaubelet boðe ueole and feire,’ where other MSS. read ‘beawbelez’ and ‘beaubelez.’

page 17 note 2 A Bacheler signified a novice, either in arms or in the church. Thus in P. Plowman, Prol. 87, we find ‘Bischopes and bachelers,’ and in Chaucer, Squieres Tale, 24, Cambuscan is described as—

'sYong, fresh, strong, and in armes desirous,

As any bacheler of al his hous.’

Brachet, Etymol. Dict., has traced the word from L. Lat. baccalarius, a boy attending a baccalaria or dairy-farm, from L. Lat. baeca, Lat. vacca, a cow. See also Wedgwood, &c. ‘Bachiler, or one vnmaried, or hauyng no wife. Agamus.’ Huloet.

page 17 note 3 Probably the same as batten, to beat out, flatten: see Halliwell, s. v.

page 17 note 4 In Northamptonshire a batildore means a thatching instrument.

page 17 note 5 'sOf bay colour, bayarde, badius.’ Baret. Compare P. Bayyd, as a horse.

page 17 note 6 The stickleback. In the Ortus Vocab. we find ‘Asperagus (quaedam piscis), a banstykyll.’ Huloet has ‘Banstickle, the stickleback;’ and Baret gives ‘a banstickle, trachydra.’ Cotgrave renders ‘espinoche’ (identical with the spinatieus or ripillio of the middle ages) by ‘a sharpling, shaftling, stickling, bankstickle, or stickleback.’ In Neckam De Utensilibus (Wright's Vol. of Vocab., p. 98) we find ‘stanstikel:’ and in the Suffolk dialect, the fish is still known as the ‘tantickle.’ In Wright's Vol. of Vocab. p. 189, the word ‘stytling’ is given as the equivalent of scorpio, a kind of fish, which the editor identifies with the ‘stickleback’ ot the present day: and at p. 222, the word gamerus is rendered a ‘styklynge,’ and in the Prompt, the ‘stykelynge’ is identified with the silurus. Jamieson gives ‘Bansticke, Bantickle. The three-spined stickle-back, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Linn.’ Cooper renders Gammarus by ‘a creuis of the sea.’

page 17 note 7 'sBacbitares’ we read in the Ancren Eiwle, p. 86, ‘þe biteð oðre men bihinden, beoð of two maneres …‥ þe uorme cumeð al openliche, and seið vuel bi anoðer, and speoweð ut his atter …‥ Ac þe latere eumeð forð al on oðer wise, and is wurse ueond þen þe oðer; auh under vreondes huckel.’ In An Old Eng. Miscellany, E. E. Text Soc., ed. Morris, p. 187, we are told that ‘Alle bacbytares heo wendeþ to helle.’ Chaucer, Persone's Tale (Six Text Edition, p. 628) divides backbiters into five classes.

page 18 note 1 Mr. Nodal, in his Lancashire Glossary, B. D. Society, says ‘Bak-brede, a broad thin board, with a handle, used in riddling out the dough of oatcakes before they are put on the spittle, and turned down on the bak-stone.’ See also Wright's Prov. Dict. s. v. Backboard. Jamieson gives ‘Bawbrek, Bawbrick, a kneading-trough, or a board used for the same purpose in baking bread.’ A. S. bacan, to bake, and bred, a board. According to Ducange Rotabulum is a baker's peel.

page 18 note 2 From hebes, blunt; the blunt side of the knife. ‘Blunt man. Hebes.’ Huloet.

page 18 note 3 'sBlatta, a litell wourme or flie, of the kynde of mothes, and hurteth bothe cloth and bookes.’ Cooper. ‘Chauvesouris, a batte; a Flittermouse; a Reeremouse.’ Cotgrave. Jamieson gives ‘Bak, Backe, Bakie-bird. s. The bat or rearmouse.’ Compare Dan. aftenbakke, lit. evening-bat. See Wyclif, , Levit. xi. 19Google Scholar. In the Poem on the Truce of 1444, printed in Wright's Political Poems, ii. 216, we read:

'sNo bakke of kynde may looke ageyn the sunne,

Of ffrowardnesse yit wyl he fleen be nyght,

And quenche laumpys, though they brenne bright.’

And again, p. 218:

'sThe owgly bakke wyl gladly fleen be nyght,

Dirk cressetys and laumpys that been lyght.’

In the Alliterative ‘Alexander & Dindimus,’ E. E. Text Society, ed. Skeat, l. 123, we find:

'sMinerua men worschipen, in oþur maner alse

& bringen heere a niht-brid, a bakke or an oule.’

See also Baoke. ‘Vespertilio. A bakke.’ Medulla. See Halliwell, s. v.

page 18 note 4 Properly a female baker. A. S. bœcistre. In P. Plowman, Prol. 217, we read:

'sI seiз in this assemble, as зe shul here after,

Baxsteres and bewsteres, and bocheres manye;’

And again, Passus iii. 79,

'sBrewesteres and bakesteres, bocheres and cokes.’

page 18 note 5 Pronuba, which in Classical Latin signified a ‘bridesmaid,’ in Low Latin degenerated to the meaning of a ‘procuress,’ in which sense it occurs several times in the Liber Albus (see, for instance, p. 454, ‘De pœna contra meretrices, pronubas, presbyteros adulteros, &c. and, p. 608, a record of a sentence lo the pillory of a woman ‘quia communis Meretrix et Pronuba’). In Wright's Volume of Vocabularies, p. 217, we find it given, as here, as the Latin equivalent of ‘bawdstrott’ (i.e. ‘an old woman who runs about on bawds’ errands’), and again in the French Royal MSS. 521 and 7692 it is translated by ‘bawdestrot’ and ‘bawdetrot.’ In the Pictorial Vocabulary of the 15th Century, printed in the same volume, p. 269, this is corrupted, evidently from the scribe's ignorance of the meaning of the word, into ‘bawstrop’ and in the Medulla into ‘bauds strok.’ A ‘trot’ was a common expression of contempt applied to old women in Early English; thus in De Deguileville's Pilgrymage of the Life of the Manhode, MS. of St. John's College, Cambridge, If. 71, the Pilgrim addresses Idleness as ‘þou aide stynkande tratte …. and than the olde tratt answerde me,’ &c.; and again, If. 73, ‘When this aide tratte hadde thus spoken.’ Cf. ‘This lere I learned of a beldame trote.’ Affectionate Shepherd, 1594. See Jamieson, s. v. Trat. ‘Paranympha: pronuba que viro nympham iungit. Paranymphus: dicitur qui nubentibus preest, vel eis assistit: vel amicus sponsalis qui eos coniungit: vel nuncius intertnedius.’ Ortus Vocab. See Ducange, s. v. Paranymphus.

page 19 note 1 Harrison in his Description of England, ed. 1587, p. 79a, says, ‘From hence [Milford] about foure miles is Saluach creeke, otherwise called Saueraeb, whither some fresh water resorteth; the mouth also thereof is a good rescue for balingers as it (I meane the register) Baith.’ ‘Celox. A brigantine, or barke.’ Cooper. Jamieson gives ‘Ballingar, Ballingere. s. A kind of ship.’ In the Paston Letters, ed. Gairdner, , i. 84Google Scholar, there is a letter giving an account of the capture of certain French ships, amongst which are enumerated ‘the grete shyp of Brast [Brest], the grete schyp of the Morleys, the grete schyp of Vaung, with other viij. schyppis, bargys, and balyngers, to the number of iij. mll men.’ The term also occurs in the Verse Life of Joseph of Arimathea (ed. Skeat), l. 425, where the writer addresses Joseph as ‘Hayle, myghty balynger, charged with plenty.’ ‘Balingaria. Bellicæ Species navis.’ Ducange. ‘Balinger or Balangha. A kind of small sloop or barge; small vessels of war formerly without forecastles.’ Smyth, Sailor's Word-Book, 1867Google Scholar. See also Way's note in Prompt, s. v. Hulke, p. 252. In the version of Vegecius, Reg. MS. 18 A. xii. are mentioned ‘small and light vessels, as galeies, barges, fluynnes and ballyngers:’ lib. iv. cap. 39. Walsingham relates that in the engagement between the Duke of Bedford and the French, in 1416, the former ‘cepit tres caricas, et unam hulkam, et quatuor balingarias.’ Camden, 394. See also Lyndesay, Monarche, Bk. ii. l. 3101.

page 19 note 2 'sBalke, a ridge of land betwene two furrowes, lyra.’ ‘A balke, or banke of earth raysed or standing vp betweene twoo furrowes: a foote stole or step to go vp, scamnum.’ ‘A balke in the cornefielde, grumus: to make balkes imporcare.’ Baret. ‘Porca. A ridge, or a lande liynge betweene two furroes wheron the come groweth: sometime a furrow cast to drayne water from come: also a place in a garden with sundrie beddes.’ Cooper. ‘Assilloner. To baulke, or plow up in baulkes.’ Cotgrave. See also Tusser, ed. Herrtage, p. 141, stanza 2, and P. Plowman, B. vi. 109. ‘The balke, that thai calle unered lande.’ Palladius on Husbandrie, E. E. Text Soc., ed. Lodge, p. 44, l. 15.

page 19 note 3 'sHic testiculus, a balok-ston; hic piga, a balok-kod.’ Nominale MS. 15th cent. ‘Couille, a cod, bollock, or testicle.’ Cotgrave. It appears from Palsgrave's Acolastus, 1540, that balloche-stones was a term of endearment.

page 19 note 4 MS. vectebra. The hinge. In Mr. Peacock's Glossary of Manley and Cottingham (E. Dial. Soc.) is given ‘Band; the iron-work on a door to which the hinges or sockets are fastened. Bands; the iron-work of hinges which projects beyond the edge of the door; frequently used for the hinge itself.’ Cooper gives ‘Vertebra, a joynte in the bodie, where the bones so meete that they may turne, as in the backe or chine.’ ‘Bands of a door; its hinges.’ Jamieson. See quotation from Ducange in note s. v. Brandyth to set byggyng on. ‘Vertebra. A dorre barre.’ Medulla. ‘And the зates of the palace ware of evour, wondir whitt, and the bandes of thame, and the legges of ebene.’ Life of Alexander the Great, Thornton MS. If. 25.

page 19 note 5 Florio has ‘Bandelle, side corners in a house.’ It seems here to be a joist. Cooper gives ‘laquear, a beame in a house. Compare P. Lace of a Howserofe. Laquearium.

page 19 note 6 'sCrusta. Bullions or ornamentes of plate that may be taken off.’ Cooper. See Copbande and Cartebaud.

page 20 note 1 'sMastive, Bandog, Molossus.’ Baret. ‘The tie-dog or band-dog, so called bicause manie of them are tied up in chaines and strong bonds, in the daie time, for dooing hurt abroad, which is an huge dog, stubborne, ouglie, eager, burthenous of bodie (and therefore but of little swiftnesse), terrible and fearfull to behold, and oftentimes more fierce and fell than anie Archadian orCorsican cur They take also their name of the Word ‘mase’ and ‘ theefe’ (or ‘master theefe’ if you will), bicause they often stound and put such persons to their shifts in townes and villages, and are the principall causes of their apprehension and taking.’—Harrison, Descrip. of England, part i. pp. 44–5. ‘We han great Bandogs will teare their skins.’—Spenser, Shep. Cal. September. See also Tusser's Fire Hundred Points, &c, E. Dial. Soc., ed. Herrtage, ch. 10, st. 19. ‘Latrator molossus. A barkynge bandogge.’ Cooper. Wyclif, Eng. Works, ed. Matthew, , p. 252Google Scholar, speaks of ‘tey dogges.’

page 20 note 2 A very literal translation of the English bonfire.

page 20 note 3 See the Chester Plays, i. 1, from which it appears that the proclamations of the old mysteries were called Banes. ‘Ban. A proclamation with voice, or by sound of trumpet.’ Cotgrave. ‘Prœludium. A proheme; in Musicke a voluntary before the Songe; a flourish; a preamble or entrance to a mattier, and as ye would say, signes and profers.’ Cooper. Compare the phrase ‘the banns of marriage.’ A. S. ban.

page 20 note 4 'sHim wol i blame and banne, but he my bales amende.’ William of Palerne, ed. Skeat, 476; see also 1.1644. In the Anturs of Arthur, ed. Robson, VII. xi. we read ‘I banne þe birde þat me bar.’ A. S. bannan, O. Icel. banna.

page 20 note 5 'sBannock, an oat-cake kneaded with water only, and baked in the embers.’ Ray's Gloss.; and see Jamieson, s. v. Gaelic bonnack.

page 20 note 6 'sBrysewort, orbonwort, or daysye, consolida minor, good to breke bocches.’ Reg. MS. 18 A, vi. leaf 72b. ‘In battill gyres burgionys the banwart wild.’ Gawin Douglas, Prologue to Book xi. of Æneid, l. 115. A. S. banwyrt. Kennett's Glossary, Lansdowne MS. 1033 explains it as the violet. According to Cooper, bellis is ‘the whyte daysy, called of some the margarite, in the North banwoort.’ Bosworth says ‘perhaps the small knapweed.’ ‘Daysie is an herbe þat sum men called nembrisworte ofer banewort.’ Gl. Douce, 290. Cockayne, Leechdoms &c, vol. ii. 371, and, iii. 313, defines it as the wall-flower.

page 20 note 7 Cotgrave has ‘Barbacane f. a casemate; or a hole (in a parrapet, or towne wall) to shoot out at; some hold it also to be a Sentrie, Scout-house, or hole; and thereupon our Chaucer useth the word Barbican for a watch-tower, which in the Saxon tongue was called, a Bourough-kenning.’

page 21 note 1 'sNefrens, a weaned pigge: maialis, barrow hogges: verres, a tame bore.’ Cooper.

page 21 note 2 A spear for boar-hunting. Cooper gives ‘Venabulo excipere aprum; to kill a boare with an hunting staffe.’ ‘Excipulum, i.e. venabulum. A spere to slee a bore with.’ Ortus Vocab.

page 21 note 3 The Addit. MS. is here undoubtedly correct. The word is the O. Fr. berfroi, from which, through the L. Lat. belfredus, comes our belfry. It was a movable tower, often of several stories high, used by besiegers for purposes of attack and defence. The following quotation from Ducange will sufficiently explain the construction of the machine, as well as the stages by which the name came to be applied in the modern sense. ‘Belfredus. Machina bellica lignea in modum excelsioris turris exstructa, variis tabulatis, coenaculis seu stationibus constans, rotisque quatuor vecta: tantae proceritatis ut fastigium oppidorum et castrorum obsessorum muros aequaret. In coenaculis autem collocabantur milites qui in hostes tela continuo vibrabant, aut sagittas emittabant: infra vero viri robore praestantes inagnis impulsibus muris inachinam admovebant. Gallicè, beffroi. Belfredi nomen a similitudine ejusmodi machinae bellicae postea inditum altioribus turribus quae in urbibus aut castris eriguntur, in quarum fastigio excubant vigiles qui eminus adventantes hostes, pulsata quae in eum finem affensa est campana, cives admonent quo sint ad arma parati. Nec in eum tantum finem statutae in belfredi campanae, ut adventantes nuntient hostes, sed etiam ad convocandos cives et ad alios usus prout reipublicae curatoribus visum fuerit. Unde campana bannalis dicitur, quod, cum pulsatur, quicunque intra bannum seu districtum urbis commorantur ad conventus publicos ire teneantur. Denique helfredum appellant ligneam fabricam in campanariis, in quibus pendent campanae. Fustibalus. Machinae bellicae species: engin de guerre, espece de fronde.’ In the Romance of Sir Ferumbras, E. E. Text Soc. ed. Herrtage, l. 3171, when Balan is besieging the French knights in the Tower of Aigremont, King Sortybran advises him to make use of his ‘Castel of tre þat hiзt brysour …

And pote þer-on vj hundred men, þat kunne boþe launce and caste.’

The tower is accordingly brought up, and is described as follows, ll. 3255–3270.

'sIn þat same tre castel weren maked stages thre:

þe hezeste hiзt mangurel; the middle hiзt launcepre;

þe nyþemest was callid hagefray; a quynte }>yng to se …

pan þe heþest stage of al fulde he with men of armes

To schelde hem by-nyþe wel fram stones and othere harmes, …

And on þat oþer stage amidde ordeynt he gunnes grete,

And oþer engyns y-hidde, wilde fyr to caste and schete.

þyder þanne he putte y-nowe, and tauзte hem hure labour,

Wilde fyr to schete and þrowe aзen þe heзe tour,

In þe nyþemest stage þanne schup he him-selue to hove,

To ordeyne hure fyr þar-inne, and send hit to hem above.’

page 21 note 4 Capt. Harland in his Glossary of Swaledale (E. D. Soc.) gives ‘Barfam, or Braffam, a horse-collar,’ as still in use. It is also used in the forms hamberwe and hamborough, and means a protection against the hames. ‘Hec epicia; Anglice, a berhom.’ Wright's Vol. of Vocab. p. 278. See Wedgwood, s. v. Hames, and Barkhaam in Brookett's Glossary. Jamieson, s. v. Brechame. A. S. beorgan, to protect, and Eng. hames. And see also Hame of an horse.

page 22 note 1 The game of prisoners'-base. In the Metrical Life of Pope Gregory (MS. Cott. Cleopatra, D ix. If. 156, bk.), we read—

'sHe wende in a day to plawe

þe children ournen at þe bars.’

In the margin of the Metrical Vocab. printed in Wright's Vol. of Vocab., p. 176, is written ‘Barri, -orum sine simgulari, sunt ludi, Anglice, bace,’ and in Myrc's Instructions for Parish Priests, E. E. Text Society, ed. Peacock, p. 11. l. 336, directions are given that games or secular business are not to be permitted in a churchyard:—

'sBal and bares and suche play,

Out of chyrcheзorde put away;

Courte holdynge and suche maner chost,

Out of seyntwary put þou most.’

Cotgrave gives ‘Barres, the martial sport called Barriers; also the play at Bace, or Prison Bars.’ In ‘How the Good Wife Taught her Daughter,’ printed in the 3rd part of Barbour's Bruce, ed. Skeat, p. 528, l. 114, children are cautioned not

'sOppinly in the rew to syng,

Na ryn at bares in the way.’

See ‘Base, or Prison-base, or Prison-bars,' in Nares’ Glossary.

page 22 note 2 According to the Medulla, cortex is the outer, liber the middle, and suber the innermost bark of a tree:—‘Pars prior est cortex, liber altera, tercia suber.’

page 22 note 3 'sGremium. A barme, or a lappe.’ Medulla.

page 22 note 4 'sLimus. A garment from the nauell downe to the feet.’ Cooper. In De Deguileville's Pilgrimage of the Lyf of the Manhode, MS. John's Coll. Camb., leaf 121, we read ‘The skynne of whiche I make my barmclothe es schame and confusioun.’ See also Napron. ‘Limas. A naprone or a barme clothe.’ Medulla.

page 22 note 5 'sBarme, or yeaste. Flos vel spuma ceruisiae.’ Baret.

page 22 note 6 'sBarnacles, an instrument set on the nose of vnruly horses, pastomis.’ Baret. ‘Camus; a bitte, a snaffle.’ Cooper. ‘Chamus. A bernag for a hors.’ Medulla. The Medulla further explains Chamus as ‘genus freni, i. capistram, et pars freni Moleyne. ‘Camus. A byt or a snaffle.’ Elyot. See Byrnacle and Molane of a brydelle.

page 22 note 7 'sCiconia. A bernag or a botore’ Medulla. ‘Barnacle byrdes. Chenalopeces.’ Huloet.

page 22 note 8 'sMercy on's, a Barne? A very pretty barne; a boy, or a childe I wonder?’ Shakspere, , Winter's Tale, III, iii. 70–1Google Scholar. ‘I am beggered, and all my barnes.’ Harrison, ed. Furnivall, i. 108.

page 22 note 9 'sVecticulus. A barwe. Vecticularius. A barwe maker.’ Medulla.

page 23 note 1 Halliwell quotes from the Romance of Sir Degrevant, If. 131:—

'sAt the baresse he habade,

'sThe folk that assalзeand wer

At mary зet, to-hewyn had

And bawndonly downe lyghte.’

The barras, and a fyre had maid

At the draw-brig, and brynt it doune.’

Barbour's Bruce, ed. Skeat, xvii. 754.

And at þe baress he hym sette.’

Sir Ferumbras, ed. Herrtage, l. 4668.

'sEnfachoun ys to þe зeate y-come,

And haueþ þat mayl an honde y-nome,

'sBarrace, Barras, Barres, Barrowis (1) A barrier, an outwork at the gate of a castle, (2)An enclosure made of felled trees for the defence of armed men.’ Jamieson. O. Fr. barres, pl. of barre, a stake. ‘Vallum. A bulwarke or rampyre.’ Cooper.

page 23 note 2 See also Berewarde. For archophilax read arctophylax. The term is generally applied to the constellation Böotes, or Charles' Wain. See Charelwayn.

page 23 note 3 A light helmet worn sometimes with a movable front. See Strutt, , ii. 60Google Scholar. It did not originally cover any part of the face, but it was afterwards supplied with visors. See Meyrick, Antient Armour.

page 23 note 4 The baselard was of two kinds, straight and curved. By Statute 12 Ric. II, cap. 6, it was provided that ‘null servant de husbandrie ou laborer, ne servant de artificer, ne de vitailler porte desore enavant baslard, dagger, nespee (nor sword) sur forfaiture dicelle.’ In the Ploughman's Tale, printed in Wright's Polit. Poems, i. 331, we read that even priests were in the habit of wearing these arms, though against the law:—

'sBucklers brode and sweardes long,

Baudrike, with baselardes kene,

Soche toles about her necke they honge

With Antichrist soche priestes bene.’

In Fairholt's Satirical Songs on Costume, Percy Society, p. 50, is a song of the 15th century beginning ‘Prenegard, prenegard, thus bere I myn baselard.’ ‘Bazelarde: ensis gladiolus.’ Manip. Vocab. ‘Sica. A short swerde.’ Medulla. See also Liber Albus, pp. 335, 554, and 555Google Scholar, and Prof. Skeat's Notes to P. Plowman, iv. 461–7. ‘Sica. A short swoorde or dagger.’ Cooper.

page 23 note 5 'sPhaselus. A little shippe called a galeon.’ Cooper.

page 24 note 1 Alexander Neckam in hia work De Naturis Rerum, Rolls Series, ed. Wright, p. 457, thus speaks of Bath:— ‘Balnca Bathoniae ferventia tempore quovis

aegris festina saepe medentur ope.’

page 24 note 2 'sSimilago; fyne meale of corne, floure.’ Cooper. Still in common use as in ‘batter-pudding.’

page 24 note 3 This line is repeated in the MS.

page 24 note 4 'sGrisard. m. A Badger, Boason, Brocke or Gray. Taieson. m. A Gray, Brock, Badger, Bauson.’ Cotgrave. See also Brokk.

page 24 note 5 I have not been able to identify this bird, but it has been suggested that the name is probably one given in imitation of the noise made by some bird of the curlew kind.

page 24 note 6 'sThou art abowteward, y undurstonde,

To wynne alle Artas of myn honde,

And Wynne my doghtyr shene.’

Sir Eglamour, l. 658.

page 24 note 7 In the fable of the Cat and the Mice, Prologue to P. Plowman, l. 161, the old rat tells his hearers that in London he has seen people walking about wearing ‘Bíзes ful brз5te abouten her nekkes.’ In Wyclif's version of Genesis xxxviii. 18, we find ‘Judas seide, What wilt thou that be зouen to thee for a wed? Sche answeride, thi ring and thi bye of the aarm, and the staffe whiche thou holdist in thin hond.’ The word also occurs in Legends of the Holy Rood, pp. 28, 29, l. 134, and in the Story of Genesis and Exodus. (E. E. Text Society, ed. Morris), i. 1390. A.S. beaз, beak, O. Icel. baugr, a bracelet, a collar. Dame Eliz. Browne in her Will, Paston Letters, iii. 464, bequeaths ‘A bee with a grete pearl. A dyainond, an emerawde . … a nother bee with a grete perle, with an emerawde and a saphire, weighing ij unces, iij quarters.’ In Sir Degrevant, Thornton Romances, ed. Halliwell, p. 200, l. 556, we find ‘broche ne bye.’

page 24 note 8 In the Anturs of Arthur, Caraden Society, ed. Robson, , xxxii. 7Google Scholar, the knight addressing the king says,

'sQuethir thou be Cayselle or Kyng, here I the be-calle,

For to fynde me a freke to feзte on my fille.’

page 24 note 9 It was not an unusual custom for men, even of the highest rank, to sleep together; and the term bed-fellow implied great intimacy. Dr. Forman, in his MS. Autobiography, mentions one Gird as having been his bed-fellow. MS. Ashmol. 208. See also Paston Letters, iii. 235, where, in a letter from Sir John Paston to John Paston, we read ‘Sir Robert Chamberleyn hathe entryd the maner of Scolton uppon your bedffelawe Converse.’ It was considered a matter of courtesy to offer your bedfellow his choice of the side of the bed. Thus in the Boke of Curtasye, printed in the Babees Boke, ed. Furnivall, , p. 185Google Scholar, we are told:—

'sIn bedde yf þou falle herberet to be

With felawe, maystur, or her degre,

þou schalt enquere be curtasye

In what part of þe bedde he wylle lye.’

page 24 note 10 'sFultrum, lecti. A bedsteade.’ Cooper. ‘Fultrum est pes lecti: sponda est exterior pars lecti.’ Wright's Vol. of Vocab., p. 242.

page 25 note 1 Bedgate, bed-time, going to bed: see Introduction to Gest Historiale of the Destruct. of Troy (E. E. Text Society, ed. Panton and Donaldson), p. xx, where the mistake in Halliwell's Dict, is corrected. ‘Corticinium. Bedde time, or the first parte of the night, when men prepare to take rest, and all thinges be in silence. After Erasmus it semeth to be the time between the first cockecrowyng after midnight, and the breake of the day. Coneubium. The stille and diepest parte of the night.’ Cooper. See Bedtyme.

page 25 note 2 'sBeddred, one so sicke he cannot rise, clinicus.’ Baret. In the Babees Boke (E E. Text Society, ed. Furnivall), p. 37, l. 19, we are enjoined ‘þe poore & þe beedered loke þou not loþe.’ And in the Complaint of Jack Upland, printed in Wright's Political Poems, ii. 22, in his attack on the friars, he says:—

'sWhy say not зe the gospel

In houses of bedred men,

As ye do in rich mens,

That mowe goe to church and heare the gospel.’

'sClinicus. A bedlawere.’ Medulla. See Stow's Survey, ed. Strype, I. bk. ii. p. 23.

page 25 note 3 'sBedstocks, bedstead.’ Whitby Glossary. Still in common use in the North. Mr. Peacock's Gloss, of Manley, &c., gives ‘Bedstockes, the wooden frame of a bed.’ ‘Three bedstoks are mentioned in the Inventory of Robert Abraham, of Kirton-in-Lindsey, 1519.’ Gent. Mag. 1864, i. 501. ‘Sponda. Exterior pars lecti.’ Medulla. See Bedfute, above.

page 25 note 4 A certain quantity of litter (rushes or straw) was always included in the yearly allowance to the chief officers of an establishment. Thus in the Boke of Curtasye, printed in the Babees Book, ed. Furnivall, amongst the duties of the Grooms of the Chamber we find they are to

'smake litere,

ix fote on lengthe without diswere;

vij fote y-wys hit shalle be brode,

Wele watered, I-wrythen, be craft y-trode,

Wyspes drawen out at fete and syde,

Wele wrethyn and turnyd agayne þat tyde:

On legh onsonken hit shalle be made,

To þo gurdylstode hegh on lengthe and brade, &c.’

In the Household Book of Edward II (Chaucer Society, ed. Furnivall), p. 14, we are told that the King's Confessor is to have ‘litere for his bede al the зere.’ ‘Hoc stramentum; lyttere.’ Wright's Vocab., p. 260. ‘Y schal moiste my bedstre with my teeris.’ Wyclif, Psalms vii. 7. See also Lyter.

page 25 note 5 'sBedde tyme, or the fyrste parte of the nyghte. Contisinium.’ 1552. Huloet.

page 25 note 6 'sCauillor. To iest: to mocke: to cauill: to reason subtilly and ouerthwartly upon woordes. Cauillator. A mocker: a bourder: a cauillar, or subtill wrester.’ Cooper.

page 26 note 1 'sPolliceor. To behestyn.’ Medulla. See P. Hotyn.

page 26 note 2 'sForasmuche as …. the king …. hath he stured by summe from his lernyng, and spoken to of diverse matters not behovefull.’ Paston Letters, ed. Gairdner, i. 34. See also Pecock's Repressor, ed. Babington, , p. 47Google Scholar. ‘Behoueable. Oportunus.’ Huloet.

page 26 note 3 MS. to Beke wandes. The Ortus Vocab. gives ‘explorare: to spye, or to seke, or open, or trase, or to becke handes.’

page 26 note 4 'sAnnuo. To agree with a becke to will one to doe a thing. Nuto. To becken, or shake the heade.’ Cooper. ‘Becken wyth the finger or heade. Abnuo, Abnuto.’ Huloet.

page 26 note 5 'sA Beacon, specula, specularium, pharus.’ Baret. See The Destruction of Troy, ed. Donaldson and Panton, l. 6037. ‘Bekin, a beacon; a signal.’ Jamieson. A. S. beacn.

page 26 note 6 In the Cursor Mundi (E. E. Text Society, ed. Morris, Gottingen MS.), p. 515,1. 8946, we read—

'sþai drow it [a tree] þedir and made a brig,

Ouer a littel becc to lig;’

and in Harrison's Descript. of England, 1587, p. 50a, the river ‘Weie or Waie’ is described as running towards ‘Godalming, and then toward Shawford, but yer it come there it crosseth Craulie becke, which riseth somewhere about the edge of Sussex short of Ridgeweie,’ &c. ‘Hic rivulus, a bek.’ Wright's Vol. of Vocab., p. 239.

page 26 note 7 Harrison, speaking of the fashions of wearing the hair in his time, says:—‘if [a man] be wesel becked, then muche heare left on the cheekes will make the owner looke big like a bowdled hen, and so grim as a goose,’ ed. Furnivall, , i. 169.Google Scholar

page 26 note 8 'sGlaber, smooth without heare; pilde.’ Cooper. ‘Beld, adj. bald, without hair on the head. Beldness, Belthness, s. baldness.’ Jamieson.

page 27 note 1 See also to Ryfte. ‘To bealke, or breake winde vpward, ructo; a bealking, ructus; to belke, ructo; a belche, ructus.’ Baret. In P. Plowman, B. v. 397, Accidia (Sloth) we are told, ‘bygan benedicite with a bolke, and his brest knokked, And roxed and rored, and rutte atte last;’

and in the Towneley Mysteries, p. 314:—

'sIn slewthe then thai syn, Goddes workes thai not wyrke, To belke thai begyn, and spew that is irke.’

'sRuctor, to rospyn: ructuus, a зyskyng’ Medulla.

page 27 note 2 See Burbylle in the water, and P. Burbulle. ‘Bulla, a bubble of water when it reyneth, or a potte seetheth.’ Cooper. ‘A bubble of water, bulla.’ Baret. ‘Bulla. A burbyl, tumor laticis: bullio, Bolnyng of watere. Scaleo. To brekyn vp or burbelyn.’ Medulla. ‘Bulla. A bubble rysing in the water when it rayneth.’ Withals.

page 27 note 3 A watchman. Cf. ‘the bellman's drowsy charm.’ Milton, , Il Penseroso, 83.Google Scholar

page 27 note 4 In the Satirical Poem on Bishop Boothe, printed in Wright's Political Poems, ii. 229, we read ‘Bridelle yow bysshoppe and be not to bolde,

And biddeth youre beawperes se to the same:

Cast away covetyse now be ye bolde,

This is alle ernest that ye call game:

The beelesire ye be the more is youre blame.’

See also P. Plowman, C. xi. 233, and compare Beldam in P.

page 27 note 5 Ducange gives ‘Ceston. Zona, Veneris … Latini dixerunt Cestus. Cesta. Vinculum, Ligamen … Graece κεστὸς muliebre cingulum est, praecipue illa zona, qua noya nupta nuptiarum die praecingebatur a sponso solvenda.’ Cooper renders Cestus by ‘a mariage gyrdle ful of studdes, wherwith the husbande gyrded his wyfe at hir fyrst weddynge.’ ‘Cestus. A gyrdyl off lechery.’ Medulla.

page 27 note 6 'sLiciatorium, a weaver's shittell, or a silke woman's tassell, whereon silke or threade wounden is cast through the loome.’ Cooper. ‘Liciatorium. A thrumme or a warpe.’ Medulla. ‘Weauers beame, whereon they turne their webbe at hande. Iugum.’ Huloet.

page 27 note 7 A fillet or band for the hair. The Medulla renders Amiculum by ‘A bende or a kerche,’ and Withals by ‘A neckercher or a partlet.’ The Ortus says, ‘Amicilium dicitur fascia capitis: scilicet peplum, a bende or a fyllet; id est mitra virginalis. Amiculum. A bende or a kercher;’ and the same explanation is given by Baret.

page 28 note 1 'sFressa faba, Plin. A beane broken or bruysed.’ Cooper, 1586. ‘Faba fresa. Groundyn benys.’ Medulla. Pegge gives ‘Spelch, to bruise as in a mortar, to split, as spelched peas, beans,’ &c. ‘Beane cake. Fabacia. Beane meale. Lomentum.’ Huloet

page 28 note 2 From a passage in the Paston Letters, iii. 239, this term would seem to have been in common use. William Pykenham writing to Margaret Paston, says, ‘Your son Watre ys nott tonsewryd, in modre tunge callyd Benett.’ ‘Exorcista. A benet, coniurator. Exorcismus. A coniuration aзens þe deuyl.’ Medulla.

page 28 note 3 A. S. benc, O. Icel. bekkr, a bench. ‘Benohe. Cathedra, Planca, Scamnum.’ Huloet.

page 28 note 4 'sBent, gramen.’ Wright's Vol. of Vocab., p. 191. Any coarse wiry grass such as grows on a bent, a common or other neglected ground. Under this name are included Arundo arenaria, agrostis vulgaris, triticum junceum, &c. By 15 and 16 George II. c. 33, plucking up or carrying away Starr or Bent within 5 miles of the Lancashire coast ‘sand-hills’ was punishable by fine, imprisonment, and whipping. Ger. bints, bins, a rush. See Moor's Gloss, of Suffolk Words.

page 28 note 5 'sBaiulus. A porter or cariar of bourdens.’ Cooper. ‘Baiulus. A portoure.’ Medulla. See also a Berer. ‘Beare. Baiulo, Fero, Gero.’ Huloet.

page 28 note 6 'sGenorbodum. A berde.’ Medulla. P. reads ‘genobardum’ and Ortus, ‘genobradum.’

page 28 note 7 'sImpubes. A man childe before the age of xiiij, and a woman before the age of xij yeres.’ Cooper. ‘Puber. A chyld lytyl skoryd. Pubero. To gynne to heeryn. Pubes. A chyldys skore, a chyldys age.’ Medulla. The Medulla curiously renders impubes by ‘unзong,’ and impubeo by ‘vnзyagyn. ‘Beardles, or hauing no bearde. Galbris.’ Huloet.

page 28 note 8 Baret says ‘Beer or rather Bere; ab Italico Bere, i.e. bibere quod Gallicè, Boire De la biere.’ See Mr. Riley's admirable note in Glossary to Liber Custumarum, s. v. Cerveise, where he points out the fact that hops (hoppys) are frequently mentioned in the Northumberland Household Book, 1512, as being used for brewing, some ten years before the alleged date of their introduction according to Stowe. Cogan, in his Haven of Health, 1612, p. 220, tells us that beer was ‘inuented by that worthie Prince Gambrinius; Anno 1786. yeares before the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ, as Languette writeth in his Chronicle.’ On p. 217 he gives a hint how to know where the best ale is to be found—‘If you come as a stranger to any Towne, and would faine know where the best Ale is, you neede do no more but marke where the greatest noise is of good fellowes, as they call them, and the greatest repaire of Beggers.’

page 28 note 9 'sLibitina. Deeth or the beere whereon dead bodies weare caried.’ Cooper. See note in P. s. v. Feertyr. ‘Beare to cary a dead corps to burial. Capulum.’ Huloet.

page 29 note 1 See also Berande. ‘Bearer. Lator, Portitor.’ 1592. Huloet. Abcedarium.

page 29 note 2 'sBerry, v. To thresh, i. e. to beat out the berry or grain of the corn. Hence a berrier, a thresher; and the berrying-stead, the threshing-floor.’ Ray's Glossary of North Country Words,’ 1691. See also Jamieson, s. v. lcel. berja.

page 29 note 3 'sBusto. To beryn or gravyn.’ Medulla.

page 29 note 4 See also Barrewarde. Harrison, in his Description of England, ed. Furnivall, , i. 220Google Scholar, classes bearewards amongst the rogues of the time, for he says, ‘From among which companie [roges and idle persons] our bearewards are not excepted, and iust cause: for I have read that they haue either voluntarilie, or from want of power to master their sauage beasts, beene occasion of the death and deuoration of manie children in sundrie countries …‥ And for that cause there is and haue beene manie sharpe lawes made for bearwards in Germanie, wherof you may read in other.’ By the Act 39 Eliz. cap. iv, entitled ‘An Act for punishment of Rogues, Vagabonds and Sturdy Beggars,’ § II, ‘All Fencers, Bearwards, Common Players of Enterludes and Minstrels wandering abroad …‥ all Iuglers, Tinkers, Pedlers, &c.…‥ shall be adjudged and deemed Rogues, Vagabonds, and Sturdy Beggars.’ See also Shakspeare, 2 Henry VI, i. 2 and v. 1; Much Ado about Nothing, ii. 1: and 2 Henry IV, i. 2. In the Satirical Poem on the Ministers of Richard II, printed in Wright's Political Poems, i. 364, we read:—

'sA bereward [the Earl of Warwick] fond a rag;

Of the rag he made a bag;

He dude in gode eutent.

Thorwe the bag the berewarde is taken;

Alle his beres han hym forsaken;

Thus is the berewarde schent.’

page 29 note 5 'sA besant was an auncient piece of golden coyne, worth 15 pounds, 13 whereof the French kings were accustomed to offer at the Masse of their coronation in Rheims; to which end Henry II caused the same number of them to be made, and called them Bysantins, but they were not worth a double duck at the peece.’ Cotgrave. See Gloss, to Liber Custumarum, s. v. Besantus. ‘Bruchez and besauntez, and other bryghte stonys.’ Morte Arthure, ed. Brock, 3256. In P. Plowman, B. vi. 241, a reference is made to the parable of the Slothful Servant, who

'shad a nam [mina] and for he wolde nouзte chaffare,

He had maugre of his maistre for euermore after,’

where in the Laud MS. nam is glossed by ‘a besaunt,’ and in the Vernon MS. by talentum.’ Wyclif's version of the parable has besaunt; Luke xix. 16. See also Ormulum, ed. White, , ii. 390Google Scholar, and the History of the Holy Grail, E. E. Text Society, ed. Furnivall, , xv. 237. In the Cursor Mundi, p. 246, 1. 4193, we read that Joseph was sold to the Ishmaelites ‘for twenti besands tan & tald.’Google Scholar

page 29 note 6 MS. Sillicitus, silicitudinarius.

page 29 note 7 MS. Sedudus.

page 30 note 1 In the Boke of Curtasye, printed in Babees Boke, ed. Furnivall, p. 187,1. 331, we are told ‘Whil any man spekes with grete besenes,

Herken his wordis with-outen distresse,’

and in the Destruction of Troy, ed. Donaldson and Panton, 1. 10336, we read

'sTo pull hym of prese paynit hym fast

With all besenes aboute and his brest naked;’

and Chaucer says of the Parson that

'sTo drawe folk to heven by fairnesse

By good ensample, this was his busynesse.’ C. T., Prologue, 519.

A.S. biseg, bisg; bisegung, bisgung, occupation, employment; Fr. besoigne.

page 30 note 2 'sBurdo; a mulette.’ Cooper, 1584. ‘A mule ingendred betweene a horse and a sheeasse, hinnus, burdo.’ Baret.

page 30 note 3 'sColustrum. The first milke that commeth in teates after the byrth of yonge, be it in woman or beast; Beestynges.’ Cooper. The word is not uncommon. Cotgrave gives ‘Beton. m. Beest; the first milke a female gives after the birth of her young one. Le laict nouveau. Beest or Beestings.’ Originally applied to the milk of women, it is now in common use in the Northern and Eastern counties for the first milk of a cow or other animal. See Peacock's Glossary of Manley, &c. ‘Colostrium: primum lac post partum vituli.’ Medulla.

page 30 note 4 Of Betony Neckam, in his work De Naturis Rerum (Rolls Series, ed. Wright), p. 472, says,

'sBetonicae vires summatim tangere dignum

Duxi, subsidium dat cephalaea tibi.

Auribus et spleni confert, oculisque medetur,

Et stomachum laxat, hydropicosque juvat.

Limphatici sanat morsum canis, atque trementi

Quem mule vexat, lux tertia praebat opem.’

page 30 note 5 A sheaf or bundle of flax as prepared ready for the mill. ‘To beet lint. To tie up flax in sheaves. Beetinband. The strap which binds a bundle of flax.’ Jamieson. At the top of the page, in a later hand, is written ‘A bete as of hempe or lyne; fascis.’

page 30 note 6 Occa is properly a harrow. In the Medulla it is explained as ‘A clerybetel’ (? cleybetel). See to Clotte. ‘Betle or malle for calkens. Malleus stuparius.’ Huloet.

page 30 note 7 MS. betynge. Corrected from A. ‘Bractea. Gold foyle; thinne leaues or rayes of golde, siluer or other mettall.’ Cooper. ‘Braccea. A plate.’ Medulla.

page 30 note 8 'sProdicio. A trayment. Trado. To trayen.’ Medulla.

page 31 note 1 'sIntersealaris. Betwyn styles.’ Medulla.

page 31 note 2 In a later hand, at the top of the page.

page 31 note 3 See also to Bye.