No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

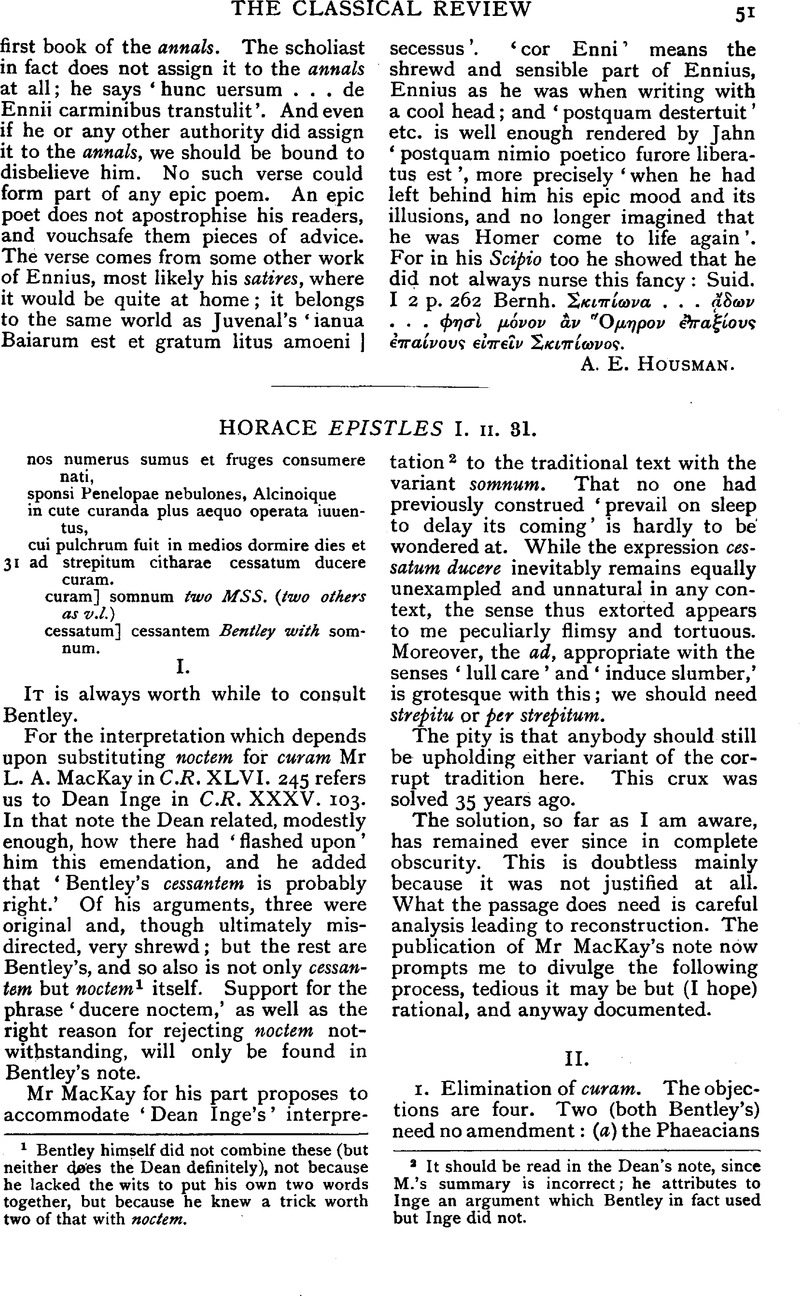

Horace Epistles I. 11. 31

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1934

References

page 51 note 1 Bentley himself did not combine these (but neither does the Dean definitely), not because he lacked the wits to put his own two words together, but because he knew a trick worth two of that with noctem.

page 51 note 2 It should be read in the Dean's note, since M.'s summary is incorrect; he attributes to Inge an argument which Bentley in fact used but Inge did not.

page 52 note 1 I believe it to be an interpolation, based on dormire, by one who, refusing (not unnaturally) to take cessatum as supine, concluded it to have been pf. ptcp. pass. in middle or ‘neuter’ sense = ‘interrupted’; as (after Schtitz, q.v.) have certain moderns, e.g. Kiessling-Heinze (ed. 4, 1914). Those who read somnum cannot account for curam.

page 52 note 2 Not to mention (e.g.) Moritz Haupt (who followed Bentley) and Munro.

page 52 note 3 See however p. 53, n. 5.

page 52 note 4 ‘The Phaeacians were not dormice’—Dean Inge, l.c.

page 53 note 1 Housman rightly insists, Introd. to Lucan p. xxxiii, that ‘Horace was as sensitive to iteration as any modern.’

page 53 note 2 Nitidi = curata cute, cf. Hor. Epist. I. iv. 15; and I may here observe that since cutem curare means ‘to give oneself a good time, treat oneself well,’ 30–31 bear out the phrase if we read cenam; they certainly do not if we read somnum.

page 53 note 3 The more so, conceivably, as cessat cantharus at Plaut. Stich. 705.

page 53 note 4 cessare, otiari et iucunde uiuere—Comm. Cruq. ad Epist. II. ii. 183.

page 53 note 5 expergisceris however is only literal in relation to 32; in regard to 32–43 generally it is metaphorical, as Kiessling-Heinze say. (They refer to ‘ps. plat. Kleitophon 408c,’ but see also the real Plato Apol. 30E … δεομνῳ γερεσθαι … ὑμς γερων.) And accordingly, if anyone should say (as one friendly critic has done) that in rejecting somnum I have removed a good link with expergisceris, I reply that in cessantes there is a far better link; for that word is the right antithesis to the figurative sense of expergiscor; cf. Ter. Ad. 4, 4, 23 (= 631) cessatum usque adhuc est, nunc porro expergiscere. For the connexion numerus … cessantes cf. Ar. Clouds 1201–3 τ κθησθ' … ριθμς and for κθημαι = to idle see Hudson-Williams, , Early Greek Elegy, p. 73Google Scholar.

page 54 note 1 If it be objected that curam is attested by the Porphyrion scholia and that P. flourished a century before A., the answer is that we really do not know for certain how much of all that matter represents the work of P. himself.

page 54 note 2 aura Peiper (followed by Evelyn White); rura V: cura Heinsius, but see line 11.

page 54 note 3 Similarly in Aul. Gell. XIX. 9, 8 Alcinous is a byword for asotia, nequitia (‘nequam et cessator Dauos’), and uoluptates cultus atque uictus. And that sleep could not consistently be more than a minor count in the indictment is also shown by Theopompus ap. Ath. XII. 531 A, where the cithara and feasting are both dwelt upon, while sleep finds no place whatever.