I. Introduction

Major international institutions such as the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Bretton Woods institutions are suffering from a crisis of legitimacy (Börzel and Zürn Reference Börzel and Zürn2021; Dingwerth et al. Reference Dingwerth, Witt, Lehmann, Reichelt and Weise2019; Lake, Martin and Risse Reference Lake, Martin and Risse2021; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). Their procedures, policies, and principles are increasingly contested. Attacks on international institutions are no longer confined to civil society actors and rising non-Western powers (Bäckstrand and Söderbaum Reference Bäckstrand, Söderbaum, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Daßler, Zangl and Kruck Reference Daßler, Zangl and Kruck2019; Kumm et al. Reference Kumm, Havercroft, Dunoff and Wiener2017; Stephen and Zürn Reference Stephen and Zürn2019; Zangl et al. Reference Zangl, Heußner, Kruck and Lanzendörfer2016). Rather, public criticism of international institutions has also been growing among established Western powers, which used to present themselves as key supporters of the ‘liberal international order’ (LIO).Footnote 1 Of the international institutions underpinning the LIO, many have become contested by established Western powers. For instance, French President Emmanuel Macron declared NATO ‘braindead’ (cited by Erlanger Reference Erlanger2019), British Prime Minister Boris Johnson alleged that the EU wanted ‘to carve up our country’ (cited by Scott Reference Scott2020) and Italy’s then-Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini called the International Monetary Fund (IMF) ‘a threat to the worldwide economy’ (cited by ANSA 2019). So far, the biggest challenge to the LIO from an established Western power stemmed from the United States under President Donald Trump, who attacked numerous of its underlying institutions (Havercroft et al. Reference Havercroft, Wiener, Kumm and Dunoff2018; Heinkelmann-Wild, Kruck and Daßler Reference Heinkelmann-Wild, Kruck, Daßler, Böller and Werner2021).

Two strands of literature yield different expectations about how established Western powers criticize international institutions. The liberal hegemony literature (Fioretos Reference Fioretos2019; Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2012; Mastanduno Reference Mastanduno2019) emphasizes that international institutions disproportionately reflect their builders’ ideas and interests. Therefore, Western powers are expected to use these institutions to cloak and legitimize their exercise of power rather than actively de-legitimize them. If they do so at all, established Western powers should engage in moderate criticism of specific institutional policies or procedures rather than fundamental principles, calling for gradual reform in the name of the international community. The populist-nationalism literature highlights how illiberal forces within Western societies shape their leaders’ stance towards international institutions and instigate a backlash against liberal internationalism (Copelovitch and Pevehouse Reference Copelovitch and Pevehouse2019; Hooghe, Lenz and Marks Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019; Koch Reference Koch2020; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). As populism rises, leaders present themselves as putting the interests of their nation first to restore an allegedly glorious past. Established Western powers experiencing a populist backlash should thus attack the very existence of international institutions in the name of national sovereignty.

While the populist-nationalism and the liberal hegemony literatures capture important aspects of institutional contestation by established Western powers, we observe considerable variation beyond their expectations. As suggested by the liberal hegemony literature, established Western powers have sometimes criticized specific practices of international institutions in the name of the international community. Italy’s criticism of the IMF for its ‘economic recipes featuring mistaken forecasts’ (Salvini, cited by ANSA 2019) provides an example, as does the Trump Administration’s criticism of the IMF’s allegedly inefficient and ineffective, and thus universally harmful, lending practices (Mayeda and Mohsin Reference Mayeda and Mohsin2018). As indicated by the populist-nationalism literature, established Western powers have at other times attacked core institutional principles from a nationalist point of view. Examples include the United Kingdom’s principled objections against the EU in the context of Brexit or the Trump Administration’s attacks of the Paris Agreement on climate change. However, we see institutional contestation that clearly deviates from the two literatures’ expectations. In some instances, established Western powers cloaked their fundamental rejection of institutions in globalist terms. For example, Germany forcefully rejected the International Energy Agency’s adherence to its principle of promoting nuclear and fossil energy for being harmful for the global fight against climate change, and the Trump Administration criticized the ‘Iran Deal’ as a danger to global security. In yet other cases, established Western powers confined their contestation to demanding reforms of particular practices while drawing on nationalist language. Take as examples France’s and Germany’s criticism of banking standards promulgated by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which they considered biased in favour of Anglo-Saxon banking systems (Kruck Reference Kruck2011: 149–52), or the Trump Administration’s criticism of the Universal Postal Union for China’s allegedly unfair postal rates.

This considerable variation in established Western powers’ contestation of international institutions matters as different contestation frames yield differential implications for the contested institution’s legitimacy – that is, the belief that its rules and procedures are appropriate (Hurd Reference Hurd2019; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). Scholarship on framing (de Bruycker Reference de Bruycker2017; Entman Reference Entman1993; Goffman Reference Goffman1974; Klüver, Mahoney and Opper Reference Klüver, Mahoney and Opper2015; Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981), as well as on rhetorical action and arguing (Deitelhoff Reference Deitelhoff2009; Hurd 1999; Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2003) emphasizes that public speech acts are performative by inviting or dis-encouraging particular responses. Whether contestation undermines institutional legitimacy thus likely depends, inter alia, on the type of and response to contestation (Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019; Wiener Reference Wiener2018). While institutional legitimacy in general, and the (re-)legitimation of a contested institution in particular, are contingent on multiple and diverse factors, different contestation frames structure the discursive space for institutional re-legitimation in important ways.

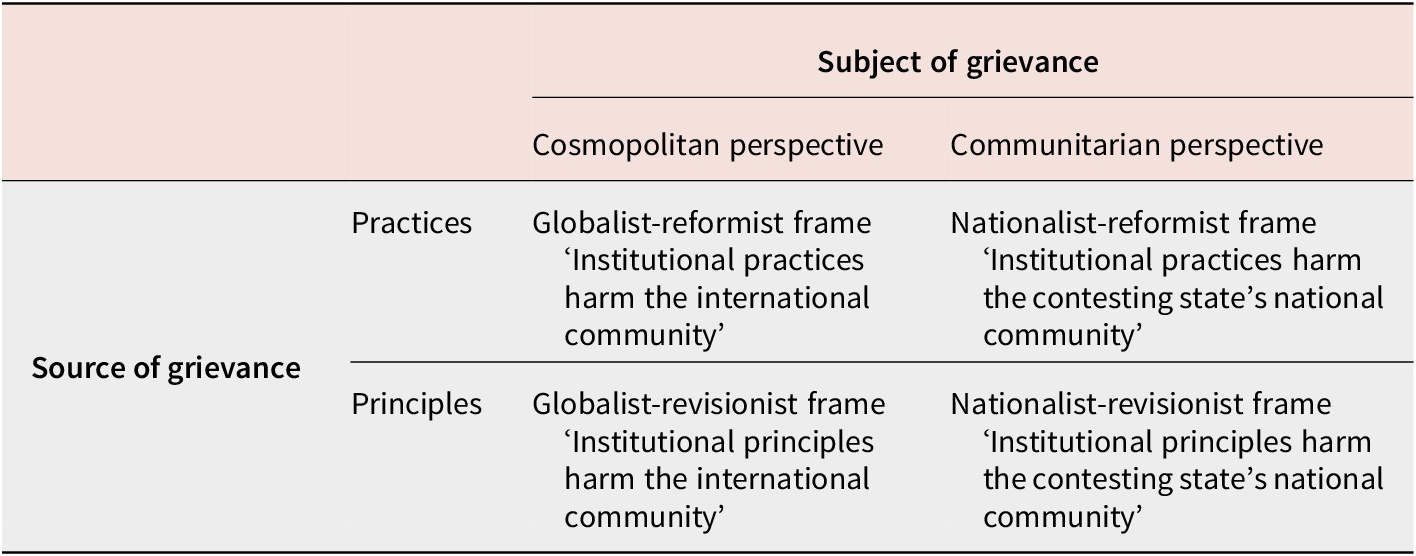

We therefore ask: How can we grasp the varying contestation of international institutions pursued by established Western powers? And how do different contestation frames shape the discursive opportunities to re-legitimate the contested institution? To provide answers to these questions, this article proceeds in two stages. We first combine insights of International Relations literature on institutional contestation as well as comparative politics literature on the ‘new cleavage’ between cosmopolitans and communitarians to develop a typology of institutional contestation frames. While institutional contestation always entails public criticism of an international institution that challenges its authority, it differs regarding, first, whether the contesting state attributes the source of grievances to specific institutional practices or underlying principles of the institution and, second, whether the contesting state presents itself or the international community as the subject of grievances. These distinctions constitute four institutional contestation frames: a globalist-reformist frame; a nationalist-reformist frame; a globalist-revisionist frame; and a nationalist-revisionist frame. In a second step, we claim that institutional contestation frames shape the discursive opportunities to re-legitimate the contested institution. We argue that the different contestation frames open up or shrink the discursive space for responses by defenders of the contested institution and are thereby associated with different opportunities to re-legitimate the institution. Different contestation frames are thus more or less conducive to a discursive re-legitimation of the contested institution.

We illustrate both steps of our argument by drawing on institutional contestation frames adopted by the Trump Administration. As an extreme case of institutional contestation by Western established powers, the numerous instances of contestation by the Trump Administration allow us to examine the whole array of contestation frames under the same government. Moreover, we can exploit the ‘breaching experimental character’ of the Trump era (Havercroft et al. Reference Havercroft, Wiener, Kumm and Dunoff2018) to demonstrate how different contestation frames by the most powerful state shape institutional defenders’ responses and thus the de-/re-legitimation discourse about contested institutions. We analyse four major international institutions that underpin the LIO, which were contested by the Trump Administration very differently: the World Bank, NATO, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and the WTO. We conclude by outlining avenues for future research.

II. A typology of institutional contestation frames

To grasp the contestation of international institutions, we propose a typology of institutional contestation frames. Communicative framing produces social meaning through the representation of an object in a specific way (Entman Reference Entman1993; Goffman Reference Goffman1974; Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981). ‘To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described’ (Entman Reference Entman1993: 52). By selecting a specific frame, the speaker emphasizes a particular point of view, thereby weakening other interpretations. Institutional contestation comprises public criticism of an international institution that challenges its authority (Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Stephen and Zürn Reference Stephen and Zürn2019; Wiener Reference Wiener2018; Zürn Reference Zürn2018). The framing can differ, depending on the source of grievance (‘What is wrong?’) and the subject of grievance against whose interests the international institution is argued to act (‘Who suffers?’).

First, drawing on the International Relations literature on institutional contestation, we distinguish whether the dissatisfied state attributes the source of grievances to institutional practices or the principles at the core of the international institution (Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019; Wiener Reference Wiener2018). Research on the contestation of international norms distinguishes two points of criticism: the contestation of their ‘validity’ and their ‘application’ (Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Wiener Reference Wiener2018, Reference Wiener2019). Along similar lines, research on the legitimacy of international institutions distinguishes between an institution’s fundamental authority and its more specific procedures or performance (Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019).

Building on these insights, we distinguish between (1) contestation frames that accept an institution in general but criticize the current practices within it and (2) contestation frames that reject the institution in general by dismissing its constitutive principles. The contestation of (procedural or policy-related) practices implies that specific grievances can be remedied within an institution through limited reforms. For instance, in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, Germany criticized the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact as too lax and therefore dangerous for the Eurozone’s stability (Buschschlüter Reference Buschschlüter2010). Rather than questioning its very principles, Germany called for reforms (Crespy and Schmidt Reference Crespy and Schmidt2014). By contrast, the contestation of institutional principles demands an institution’s large-scale change or even abolition. For instance, instead of criticizing specific practices or rules of the ‘Iran Deal’, the Trump Administration rejected its constitutive principle of allowing Iran the civil use of nuclear power and called for its termination.

Second, drawing on the comparative politics literature on the ‘new cleavage’, we conceptually distinguish whether the contesting established power presents only itself or the entire international community as the subject of grievances stemming from an international institution. Scholarship suggests that political conflicts over international institutions are increasingly fought along the lines of communitarians and cosmopolitans (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; de Wilde et al. Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel and Zürn2019; Hooghe, Lenz and Marks Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019). International institutions can be criticized from both perspectives: from a communitarian perspective, they can be contested as they infringe upon the interests and values of a particular national community (Copelovitch and Pevehouse Reference Copelovitch and Pevehouse2019); from a cosmopolitan perspective, they can be criticized for violating universal values (Kreuder-Sonnen Reference Kreuder-Sonnen2019).

Drawing on these insights, we distinguish between (1) contestation frames that operate with a nationalist point of reference presenting international institutions as damaging one’s own national community; and (2) contestation frames that operate with a globalist point of reference presenting institutions as inducing harm not only on a particular state but the entire international community. Nationalist contestation frames criticize an institution from the perspective of a particular state or its population. They claim to represent a national community that is particularly impaired by an international institution. For instance, contestation frames employed by the UK government after the Brexit referendum referred to the EU as an institution that was harmful for UK citizens. Prime Minister Theresa May framed the EU as an ‘out-of-touch class of politicians and commentators dismissive of the interests of regular [British] people’ (cited by Lewis, Clarke and Barr Reference Lewis, Clarke and Barr2019). By contrast, globalist contestation frames criticize an institution from the perspective of the society of states or even global society. They attack an institutional status quo for being harmful for all states and claim to criticize the institution in the name of all. For instance, during debates about a reform to the UN Security Council (UNSC) in the mid-2000s, the G4 (Brazil, Germany, India, Japan) criticized its lack of representativeness and stated that a more inclusive UNSC ‘would strengthen the problem-solving capacity of the Security Council’, which ‘would be in the interests of everyone’ (cited by Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2020: 97).

Combining the two dimensions – source of grievances and subject of grievances – results in four ideal-typical frames of institutional contestation (see Table 1):

-

• Globalist-reformist frame. The contesting state can criticize particular practices of an international institution, arguing that its policies or procedures create harm for the entire international community of states or individuals around the world. The contester refrains from challenging the principles of an institution but calls for reforms to specific policies or procedures. Taking a cosmopolitan perspective, it purports to voice its criticism in the name and interest of the international community rather than (only) its national community. The key message is that current institutional practices harm states and people around the world.

-

• Nationalist-reformist frame. The contesting state can also criticize specific institutional practices, but emphasize the disadvantages for its own country. While voicing its dissatisfaction with specific institutional procedures or policies, it does not question the institution’s underlying principles or purposes. Taking a communitarian view, the contester depicts the institution as harmful for its own national community. The key message is that current institutional practices harm the contesting state and its citizens.

-

• Globalist-revisionist frame. The contesting state can also criticize the fundamental principles of an institution from a globalist perspective. It then depicts the entire international community as a victim of a deeply flawed institution. The contester not only criticizes specific institutional practices, but questions the institution’s raison d’être – its core norms, principles and purposes. The purported goal is not to reform the institution, but to abolish or replace it. Taking a cosmopolitan perspective, the dissatisfied state claims that it is not (only) its own national community but the entire international community that is suffering from the institution. The key message is that the institution harms states and people around the world.

-

• Nationalist-revisionist frame. The contesting state can finally attack the underlying principles of an institution from a nationalist perspective. It then presents itself and its citizens as prime victims of the institution. The contester openly rejects the constitutive norms and principles at the heart of the institution and challenges the rationale for its continuity. Employing a communitarian perspective, the contesting state depicts its own national community as the key subject of grievances stemming from the institution. The key message is that the institution as such harms the contesting state and its citizens.

Table 1. Institutional contestation frames

III. The Trump Administration and varying frames of institutional contestation

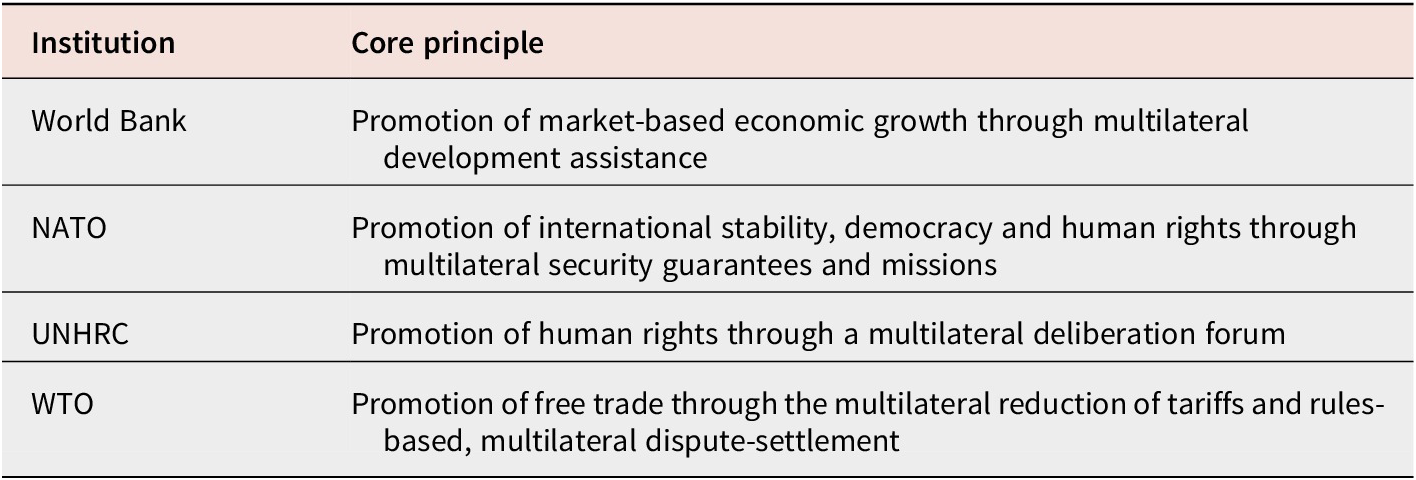

We use our typology to empirically map variation in the Trump Administration’s institutional contestation. We focus on four major international organizations (IOs) that are building blocks of the LIO, as they are multilateral in their procedures and pursue liberal objectives (see Table 2). The World Bank promotes market-based economic growth through multilateral development assistance (Marshall Reference Marshall2008); NATO not only constitutes a collective defense organization, but a ‘Western Community of liberal-democratic and multilateralist values and norms’ (Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig1998: 198) that aims at fostering international stability and liberal values by multilateral means (Lake, Martin and Risse Reference Lake, Martin and Risse2021: 8); the UNHRC promotes human rights by the means of inclusive multilateralism (Tistounet Reference Tistounet2020); and the WTO aims at trade liberalization through multilateral tariff reductions and the judicialization of dispute settlement (Hopewell Reference Hopewell2021).

Table 2. Selected international institutions and their liberal core principles

To study their contestation, we conducted a frame analysis. As an instrument for analysing public discourse and the various lines of argumentation therein, a frame analysis focuses on the production of social meaning through communicative framing (de Bruycker Reference de Bruycker2017; Entman Reference Entman1993; Klüver, Mahoney and Opper Reference Klüver, Mahoney and Opper2015; Schön and Rein Reference Schön and Rein1994). Analysing frames used by political actors allows us to retrace how speakers highlight some aspects of a perceived reality and make them salient in their statements. A framing analysis thus sheds light on how actors promote particular problem definitions, interpretations, and evaluations, while also implying recommendations for action.

We studied public statements by President Donald Trump and high-level government representatives. We drew on official press releases, the President’s Twitter account and newspaper coverage using the Factiva database. We searched for the terms ‘US’, ‘Trump’, and the name of the respective institution with a timeframe demarcated by the period from Trump’s inauguration (January 2017) to his electoral defeat (November 2020). We considered statements that referred to a source of grievances stemming from one of the four IOs and a subject of grievances. We then assessed whether criticism was limited to an institution’s practices or extended to its principles, and whether it took a primarily globalist or nationalist perspective. When one of us was uncertain about how to code a particular utterance, we jointly sought intersubjective agreement. Wherever possible, we looked for similar statements in different media outlets by different Administration officials. For each institution, we qualitatively assessed which frame was predominant in the critical statements by the Trump Administration. In the case studies below, we provide a summary of the predominant frame in our own words and numerous direct quotes from the Trump Administration that best represent the relevant frame. The observed variation in contestation frames across institutions underscores the analytical value of our typology.

The globalist-reformist contestation of the World Bank

The Trump Administration’s contestation of the World Bank took a globalist-reformist frame. It criticized specific practices in the World Bank as inefficient or inappropriate and depicted the international community and poor people around the world as prime victims. This globalist-reformist framing is epitomized by Treasury Secretary for International Affairs David Malpass’s criticism that the World Bank and other multilateral development organizations ‘spend a lot of money. They’re not very efficient. They’re often corrupt in their lending practices and they don’t get the benefit to the actual people in the countries’ (cited by Lowrey Reference Lowrey2018).

As source of grievances, the Trump Administration’s contestation targeted the World Bank’s practices, especially its lending to emerging economies such as China and its alleged bureaucratic inefficiency. It did not target its institutional principles of promoting market-based economic growth through multilateral development assistance; the Trump Administration even explicitly ‘applaud[ed] the World Bank’s emphasis on the private sector as the engine of growth’ (Mnuchin Reference Mnuchin2017: 2). Instead, Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin (Reference Mnuchin2017: 2) criticized the World Bank for its continued lending to countries that would obtain ‘substantial access’ to other sources of finance while simultaneously calling for a ‘shift in allocation towards lower middle-income countries’. Trump (Reference Trump2019e) questioned the World Bank’s lending at comparatively low rates to China: ‘Why is the World Bank loaning money to China? Can this be possible? China has plenty of money … STOP!’ However, the Trump Administration never questioned US commitment to the World Bank’s underlying principle – the promotion of market-based economic growth through multilateral development assistance – but rather criticized its inefficient or inappropriate application, as in the case of China.

Regarding the subject of grievances, the Trump Administration framed its criticism of the World Bank in globalist terms. It depicted not (only) the United States, but the international community, as the victims of the institutional status quo. The Trump Administration emphasized that it was the countries in need of development aid that were primarily suffering from the ineffective and inappropriate allocation of development funding by the World Bank. Mnuchin (Reference Mnuchin2017) demanded that the World Bank ‘strengthen its focus on outcomes, results, and accountability … to ensure that adequate resources … are available for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable’. Similarly, Malpass criticized the World Bank’s lending policies for not improving the situation of ‘the actual people in the countries’ (cited by Lowrey Reference Lowrey2018). Trump (Reference Trump2019c) also employed a globalist frame when he pushed for the so-called ‘Ivanka Fund’, which would be instrumental in ‘empowering women all across the globe’. This was echoed by Mnuchin (Reference Mnuchin2019), who demanded more instruments like the ‘Ivanka Fund’, which ‘shows commitment globally’ in order ‘to break down systemic barriers for women-owned small and medium enterprises’. The contestation of the World Bank clearly contrasts with a counterfactual nationalist framing, whereby the Trump Administration would have depicted only the United States as victim by, for instance, emphasizing that other states would take advantage of the United States as the largest contributor, thereby harming US welfare.

In sum, the Trump Administration framed its contestation of the World Bank in globalist-reformist terms by calling for reforms to the World Bank’s lending practices in the name and (presumed) interest of the poor around the world.

The nationalist-reformist contestation of NATO

The Trump Administration framed its contestation of NATO in nationalist-reformist terms by claiming that specific institutional practices have harmed the United States. The following statements are illustrative in this regard:

The United States is spending far more on NATO than any other Country. This is not fair, nor is it acceptable … Germany is at 1%, the U.S. is at 4%, and NATO benefits Europe far more than it does the U.S. By some accounts, the U.S. is paying for 90% of NATO, with many countries nowhere close to their 2% commitment. (Trump Reference Trump2018g)

The president wants a strong NATO … Why is Germany spending less than 1.2 percent of its GNP? When people talk about undermining the NATO alliance, you should look at those who are carrying out steps that make NATO less effective militarily. (Bolton, US National Security Advisor, cited by Hirschfeld Davis Reference Hirschfeld Davis2018)

Just as in the case of the World Bank, the main source of grievances put forward by the Trump Administration was specific practices. It did not attack NATO’s core principles of the promotion of stability, democracy and human rights through multilateral security guarantees and missions. The most prominent criticism was that other member states failed to live up to the 2014 objective of spending at least 2 per cent of GDP for defence by 2024. For instance, Trump (Reference Trump2018b) claimed that NATO members ‘are not only short of their current commitment of 2% (which is low) but are also delinquent for many years in payments’. By contrast, the institutional principle of multilateral security guarantees for the protection of the ‘liberal West’ was hardly contested in public.Footnote 2

In contrast to the World Bank case, the Trump Administration framed the subject of grievances in nationalist rather than universal terms. Trump portrayed the United States as a ‘sucker’ (Trump Reference Trump2019b) because other NATO members would take advantage of US contributions and, at the same time, ‘rip us off on trade’ (Trump Reference Trump2018a). Trump demanded ‘fairness’ (Trump Reference Trump2018d) and that ‘Europe should … pay its fair share of NATO’ (Trump Reference Trump2018c). Trump even asked whether ‘delinquent’ countries would ‘reimburse the U.S.’ (Reference Trump2018b) and claimed that ‘the United States must be paid more for the powerful, and very expensive, defense it provides to Germany!’ (Trump Reference Trump2017). By contrast, a globalist contestation frame might have referred to how NATO needed to be reformed to strengthen the alliance in the interest of all members. By contrast, Trump (Reference Trump2019d) stressed that, through changed NATO practices in terms of burden-sharing, ‘tremendous things [were] achieved for U.S.’.

In sum, the Trump Administration’s criticism of NATO is a case of nationalist-reformist contestation where the source of grievances are specific institutional practices, and the subject of grievances is the contester’s national community.

The globalist-revisionist contestation of the UNHRC

In its contestation of the UNHRC, the Trump Administration framed its criticism mainly in globalist-revisionist terms. Taking a globalist perspective, US officials publicly questioned its core principle of human rights protection through an inclusive multilateralist approach. The following quote by US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley (Reference Haley2017) is illustrative:

The Human Rights Council has been given a great responsibility. It has been charged with using the moral power of universal human rights to be the world’s advocate for the most vulnerable among us. Judged by this basic standard, the Human Rights Council has failed … it has been a forum for politics, hypocrisy, and evasion – not the forum for conscience that its founders envisioned. It has become a place for political manipulation, rather than the promotion of universal values. Those who cannot defend themselves turn to this Council for hope but are too often disappointed by inaction.

With regard to the source of grievances, contestation of the Trump Administration over time shifted from a mere critique of specific practices in the UNHRC to its principled rejection. Criticism initially targeted institutional practices. Haley (Reference Haley2017) called for ‘critically necessary changes’ to ‘reestablish the Council’s legitimacy’ and characterized the repeated criticism of Israel as ‘the central flaw that turns the Human Rights Council from an organization that can be a force for universal good, into an organization that is overwhelmed by a political agenda’. Trump claimed that ‘it is a massive source of embarrassment to the United Nations that some governments with egregious human rights records sit on the U.N. Human Rights Council’ (White House 2017). The Trump Administration’s contestation did not remain restricted to specific practices as it did in its contestation of World Bank and NATO. Rather, it turned against the UNHRC’s constitutive principle of promoting human rights through an inclusive multilateral approach. Together with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Haley declared the US withdrawal from the organization: although created with a ‘noble vision’, the Council would ‘not [be] worthy of its name’ and the US commitment to human rights would ‘not allow us to remain a part of a hypocritical and self-serving organization that makes a mockery of human rights’ (US Department of State 2018). This characterization of the UNHRC as a failed institution is echoed by Trump who called it ‘a grave embarrassment’ (The White House 2018) to the UN. To be sure, the Trump Administration kept underlining its commitment ‘to defend human rights at the UN every day’ (U.S. Department of State 2018). Nonetheless, its ultimate rejection of the procedural principle of inclusive multilateralism underlying the UNHRC, which has sought to integrate also states with (highly) deficient human rights records, as well as the propagation of an alternative exclusive institution featuring only ‘worthy’ partners (Koran Reference Koran2018) amounts to an attack against the institution’s core. By contrast, a reformist frame would have remained restricted to criticizing specific practices, such as unfair treatment of particular states.

As in the case of the World Bank, the subject of grievances in the Trump Administration’s critique of the UNHRC goes beyond a narrow focus on the national community. Employing a cosmopolitan perspective, Haley (Reference Haley2017) emphasized ‘the moral power of universal human rights’ as well as the global interest in their fair and transparent enforcement. By falling short of these ‘universal values’, the UNHRC would harm ‘those who cannot defend themselves’ (Haley Reference Haley2017). Trump also referred to other states’ grievances when criticizing the UNHRC for ‘shielding egregious human rights abusers while bashing America and its many friends’ (White House 2018, italics added). This clearly contrasts with a nationalist contestation, whereby the Trump Administration would only depict the United States and its citizens as victims of, for instance, unfair condemnations by the UNHRC. Instead, it portrayed the fundamental flaws of the UNHRC as harmful for global human rights protection.

In sum, the Trump Administration’s contestation of the UNHRC constitutes a case of globalist-revisionist framing, as its criticism was directed at the institution’s core and highlighted its negative effects for the international community.

The nationalist-revisionist contestation of the WTO

The US contestation of the WTO was exceptionally radical even by the standards of the Trump Administration. Embarking on a nationalist-revisionist frame, US officials denounced the WTO’s principles of free trade through multilateral tariff reductions and rules-based dispute settlement from a communitarian perspective, depicting the United States as its main victim. This frame is epitomized by statements in which Trump characterized the WTO as the ‘worst trade deal ever’ (cited by Bloomberg 2020) while opining that ‘bilateral deals are far more efficient, profitable and better for OUR workers. Look how bad WTO is to U.S.’ (Trump Reference Trump2018f). Trump described the WTO as irremediably ‘BROKEN’ (Reference Trump2019a), since ‘[t]he WTO has been a disaster for this country. It has been great for China and terrible for the United States’ (cited by Isidore Reference Isidore2018).

The source of grievances put forward by the Trump Administration not only comprised unfair procedures and practices of the WTO’s staff and other members, but US officials also rejected its fundamental principles, namely multilateral tariff reductions and rules-based dispute-settlement. This is not to deny that Trump criticized some practices of the WTO. For example, Trump (Reference Trump2018e) claimed that the WTO granted certain emerging economies such as China an ‘unfair’ competitive advantage over the United States by considering them ‘developing nation[s]’. Moreover, Trump took issue with negative rulings of its dispute settlement body: ‘The arbitrations are very unfair. The judging has been very unfair … We always have a minority and it’s not fair’ (Trump Reference Trump2018h). Sometimes attacks on the WTO’s practices were even coupled with a commitment to free trade: ‘The president is for free trade, but it must also be fair trade’ (White House 2018). However, as in the case of UNHRC, the Trump Administration’s contestation escalated to a rejection of the WTO’s principles of multilateral, non-discriminatory trade liberalization and rules-based dispute settlement. Questioning the WTO’s raison d’être in very harsh and fundamental terms, Trump (Reference Trump2018h) called the organization an outright ‘disaster’, stating ‘I’m not a big fan of the WTO’ (cited by The Guardian 2020), and even repeatedly threatened: ‘If they don’t shape up, I would withdraw from the WTO’ (cited by Micklethwaite, Taley and Jacobs Reference Micklethwaite, Talev and Jacobs2018).

The Trump Administration denounced the WTO’s multilateral, non-discriminatory approach – embodied by the most-favored-nation principle – in favor of bilateral trade agreements, which Trump (Reference Trump2018f) called ‘far more efficient, profitable and better’. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross stated that the ‘most favored nation rule hurts importers, limits U.S. trade’ (cited by Bown and Irwin Reference Bown and Irwin2018: 2). The Trump Administration’s revisionist attacks also targeted the very idea – rather than the specific procedures – of supranational rules-based dispute settlement. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer criticized the WTO Appellate Body for ‘judicial activism’, denouncing its adjudication as a ‘threat to sovereignty’ (cited by Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger2019). Trump (Reference Trump2018i) expressed his rejection of rules-based dispute settlement in statements such as ‘trade wars are good, and easy to win’. The Trump Administration lived up to its principled rejection of the WTO by blocking the appointment of new judges and thereby effectively paralysed the appeals stage in its dispute settlement (Daßler, Heinkelmann-Wild and Kruck Reference Daßler, Heinkelmann-Wild and Kruck2022).

In contrast to the globalist critique of the UNHRC, and reminiscent of the nationalist contestation of NATO, the Trump Administration hardly cloaked the subject of grievances in universalist language but depicted the United States as the victim suffering from the actions of the WTO. Trump construed the WTO as an antagonist of and danger for the American people when claiming that the organization was ‘unfair to us’ (Trump Reference Trump2018h) or ‘OUR workers’ (Trump Reference Trump2018f): ‘The WTO was set up for the benefit [of] everybody but us … They have taken advantage of this country like you wouldn’t believe’ (cited by Donnan Reference Donnan2017). By contrast, a globalist contestation frame might have referred to negative effects of the WTO’s trading system for economies or societal groups, such as workers, around the world, rather than only for the United States.

In sum, the Trump Administration employed a nationalist-revisionist framing that criticized in the name and for the sake of the US as a national community the WTO’s core principles of a multilateral, rule-based trade order.

IV. Contestation frames and re-legitimation opportunities

When established Western powers criticize international institutions, this is likely consequential for their legitimacy (Bäckstrand and Söderbaum Reference Bäckstrand, Söderbaum, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Dingwerth et al. Reference Dingwerth, Witt, Lehmann, Reichelt and Weise2019; Stephen and Zürn Reference Stephen and Zürn2019; Schmidtke Reference Schmidtke2019). Institutional contestation not only expresses the contesting actor’s disbelief in an institution’s legitimacy but may also undermine other actors’ beliefs therein. Most importantly, institutional contestation frames shape the discursive space for the contested institution’s re-legitimation (Deitelhoff Reference Deitelhoff2009; Hurd 1999; Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2003; Stephen and Zürn Reference Stephen and Zürn2019: 22–23). Each of the four contestation frames facilitates certain discursive responses by institutional defenders while constraining others. The exchange between contesters (contestation frames) and defenders (responses) constitutes distinct de-/re-legitimation discourses, which in turn affect the legitimacy of the contested institution. The framing of contestation thus ultimately matters for whether contestation turns out to be ‘proactive’, facilitating debate and (possibly) reforms of the institution that ultimately enhance its legitimacy, or whether it contributes to the ‘reactive’ unravelling of institutionalized cooperation (see Wiener Reference Wiener2018).

Two groups of actors are particularly relevant for an institution’s re-legitimation: other member states and the leadership of IOs. The leadership of IO bureaucracies matters since they have a stake in the institution (Debre and Dijkstra Reference Debre and Dijkstra2021; Gray Reference Gray2018; Hirschmann Reference Hirschmann2021; Schütte Reference Schütte2021) and will thus engage in the re-legitimation discourse to defend the institution (Heinkelmann-Wild and Jankauskas Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Jankauskas2020). Nonetheless, how they discursively engage with the contester and are able to mobilize defenders among member states are affected by institutional contestation frames. Other member states are most decisive, as the fate of the contested institution primarily hinges on their continued resource contributions and compliance (Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2007; Sommerer and Agné Reference Sommerer, Agné, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Zürn Reference Zürn2018; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). Member states, conceived as boundedly rational actors, usually prefer to stick to the familiar status quo (Jupille, Mattli and Snidal Reference Jupille, Mattli and Snidal2014) and will thus tend to defend a contested institution (Hopewell Reference Hopewell2021). The discursive space for their responses is again structured by the specific nature of contestation frames.

To be clear, in studying how contestation frames affect defenders’ re-legitimation responses, our objective is not to assess any direct effect of contestation frames on an institution’s legitimacy. Nor do we claim that different contestation frames determine a particular re-legitimation response. Other members’ commitment to an institution might vary depending on additional factors, including socialization in an institution and the material benefits from an institution, which have nothing to do with the institutional contestation frames (Fehl and Thimm Reference Fehl and Thimm2019; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni Reference Eilstrup-Sangiovanni2020, Reference Eilstrup-Sangiovanni2021). Rather, our claim is that, ceteris paribus, different contestation frames shape defenders’ discursive opportunities to re-legitimate the institution and their responses in turn matter – besides other factors – for an institution’s legitimacy.

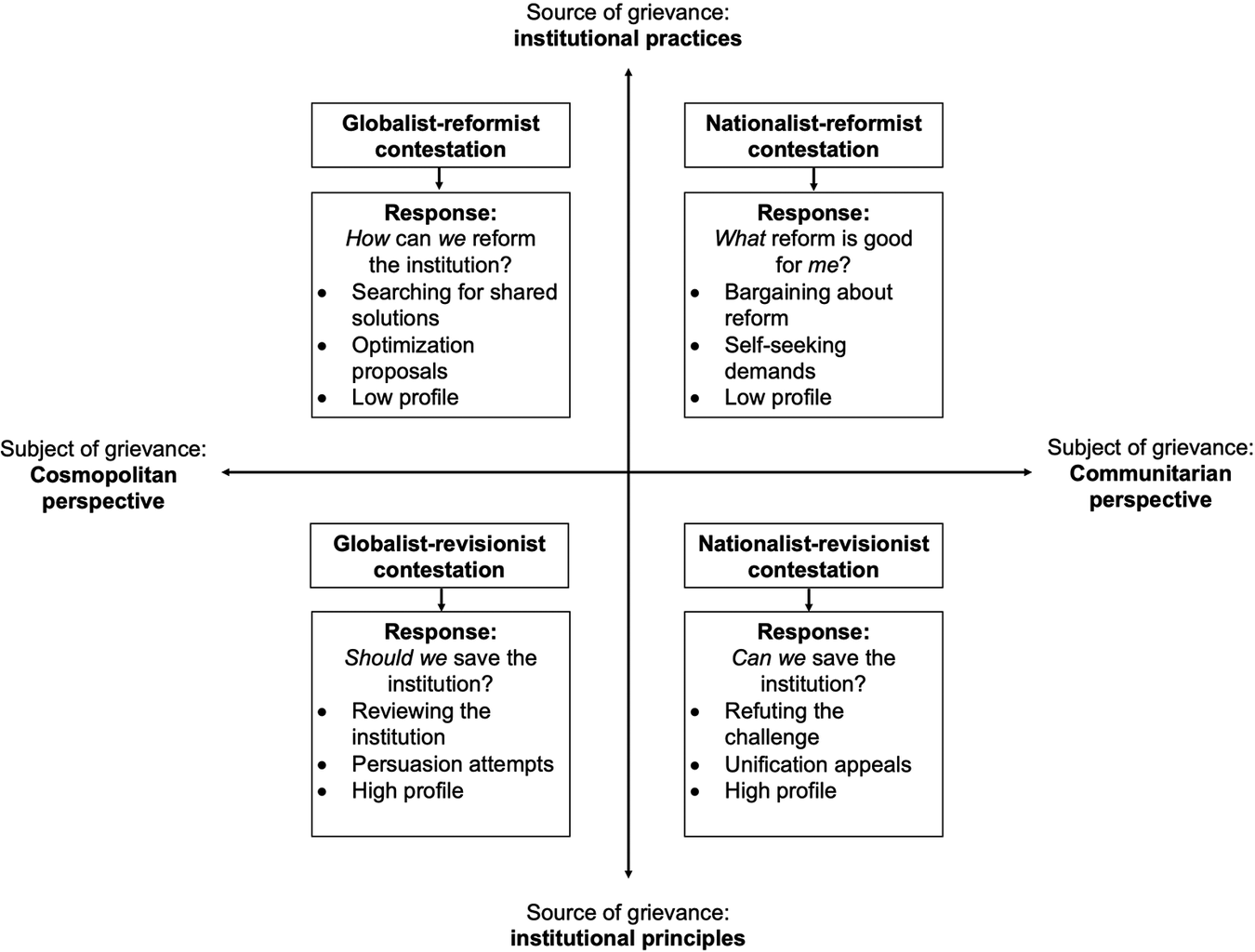

In the remainder of this section, we theorize how each contestation frame affects the discursive space for institutional defenders. When the subject of grievances is framed in cosmopolitan terms, this invites defenders to also adopt a globalist framing. By contrast, responses to contestation from a communitarian perspective will rather employ nationalist frames, too. Moreover, when the source of grievances are institutional practices, responses focusing on reforms are facilitated. By contrast, when contestation extends to institutional principles, defenders will likely be prompted to also adopt a more fundamental stance. In combination, we arrive at varying re-legitimation opportunities for defenders (see Figure 1). To illustrate our argument, we analyse IO leaders’ and other member states’ responses to the Trump Administration’s contestation of the World Bank, NATO, the UNHRC and the WTO. We again employed a frame analysis to study public statements aimed at legitimating the respective IOs, reported in newspaper coverage sourced from the Factiva database.

Figure 1 Discursive re-legitimation opportunities for institutional defenders.

Responses to globalist-reformist contestation: The case of the World Bank

Globalist-reformist contestation is unlikely to provoke stiff protest by the defenders of the institution. Rather, it invites defenders to engage in low-key debates with the contesting state, searching for shared solutions and proposing reforms that optimize the institution in the common interest.

Reformist contestation provides defenders with relatively large space for cooperative re-legitimation attempts. Compared with revisionist frames, reformist frames facilitate the search for shared solutions between contesting actors, IO leadership and defending member states. The limited dissatisfaction of contesting states and their demands for limited reform suggest a low-key response that highlights the opportunities for jointly optimizing the criticized institution. As there is a relative alignment of interests between contesters and defenders of the international institution that its key principles should not be questioned, reformist contestation keeps open avenues for gradual reform that optimizes the workings of the institution and thereby incrementally enhances its legitimacy (Kruck and Zangl Reference Kruck and Zangl2020). By contrast, a fierce response pushing back against merely reformist contestation risks being counter-productive in that it may harden the stance of the contesting actor and sour the potentially viable search for shared solutions with reformist contesting actors. Reformist frames thereby suggest responses that stress room for accommodation as well as the mutual benefits of a cooperative, legitimacy-enhancing reform. Defenders may thus respond by proposing reforms that aim at optimizing specific policies and procedures. These will likely be presented as legitimacy-enhancing, collectively desirable steps forward (see Bäckstrand and Söderbaum Reference Bäckstrand, Söderbaum, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Wiener Reference Wiener2018, Reference Wiener2019; Zürn Reference Zürn2018).

The case of the globalist-reformist contestation of the World Bank underlines the plausibility of these expectations. The World Bank’s leadership initiated discussions about joint solutions in reaction to the Trump Administration’s contestation. Regarding its criticism of the lending to China, the World Bank leadership was quick to declare that it had already fallen sharply, and that the World Bank intended to eliminate lending as countries such as China got richer and to focus its efforts more on those countries in the most pressing need (Mohsin and Harney Reference Mohsin and Harney2019). Several member states also engaged in the debate about reforming the World Bank’s lending practices to raise borrowing costs for higher-middle-income countries such as China. The United Kingdom, for instance, agreed with the reform proposal and stated that ‘the challenges and opportunities we are facing require even greater international co-operation and partnership’ (Mordaunt Reference Mnuchin2018). Even the Chinese government participated in the cooperative discursive search for acceptable solutions and supported the joint solution – a US$13 billion capital increase coupled with reforms of World Bank lending practices – as ‘a concrete measure to support multilateralism at a time when anti-globalization sentiments, unilateralism, and protectionism in trade were creating uncertainties in the global economy’ (Arab News 2018).

The other-regarding argumentation constitutive of globalist frames makes it difficult for defenders to outright reject the contesting state’s criticism. Rather, globalist frames suggest defenders discursively pick up and engage with the contester’s criticism of the institution. Phrased as a universalist argument to be shared by all, globalist frames contribute to bringing defenders into an argument about the merits and downsides of an institution for states and societies around the world. Defenders may even concede that the contester has a valid point when criticizing the institution. There is thus greater potential for deliberation about the institution, its faults and potential improvements compared with nationalist frames.

The fact that the Trump Administration framed the World Bank’s unduly favourable treatment of China and inefficiency as harmful for ‘really’ poor countries, communities and individuals around the world made it more difficult to claim this was just a power-political move to contain the growing global rival, China. Rather, the World Bank’s leadership admitted that the Trump Administration had a point. They conceded that continued lending to China was questionable and emphasized their own achievements and ambitions in ensuring that China would lose its ‘favorable lending terms’; they even promised that, as a result, China ‘will be a much smaller borrower’ in the future (Mohsin and Harney Reference Mohsin and Harney2019; Nazaryan Reference Nazaryan2019).

In sum, globalist-reformist contestation invites the defenders of the institution to ask themselves: ‘How can we reform the institution?’ Defenders will be inclined to engage in a low-key debate with the contester, searching for shared solutions and proposing reforms that optimize the institution in the common interest.

Responses to nationalist-reformist contestation: The case of NATO

In the face of nationalist-reformist contestation, the defenders of the targeted institution will likely feel prompted to engage in a low-key bargain with the contesting state, issuing their own self-seeking demands. As discussed above, grievances highlighted in reformist contestation frames invite responses from defenders that point to opportunities for cooperative, legitimacy-enhancing reform. Accordingly, German Chancellor Merkel conceded to the Trump Administration that NATO could and should be reformed. She underlined that ‘the structures in which we operate are essentially those that emerged from the horrors of the Second World War and National Socialism’. She thereby admitted the need for reform, but also emphasized that ‘I don’t think that we can simply take an axe to these structures’ (cited by Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2019). NATO’s leadership was even more explicit in embracing the Trump Administration’s reform demands. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg responded to Trump’s complaints about unfair burden-sharing within NATO by stating, ‘I welcome his [Trump’s] very strong message on defence spending, on burden sharing, and on NATO’s role in fighting terrorism, that we have to step up and do more’ (cited by McCaskill Reference McCaskill2017).

Yet, in contrast to globalist contestation, frames that emphasize national(ist) interests and corresponding unilateralist approaches to realizing them may suggest that defenders emphasize their national interests too. Nationalist contestation frames not only fail to trigger arguments about joint solutions and mutually beneficial reforms, but they may even work against them. By overtly revealing the parochial self-interest behind public criticism and reform demands, nationalist frames make it, ceteris paribus, more likely that defenders will respond in kind. This may culminate in an exchange of self-interested positions and distributive conflict – if not polarization – between contesters and defenders. We thus expect that defenders will be inclined to issue self-serving demands in response to nationalist-reformist contestation frames and a conflictual bargain about the substance of reforms, reflecting divergent national interests.

In line with these expectations, the Trump Administration’s nationalist-reformist contestation of NATO was answered with responses in which other member states pondered what Trump’s demanded reforms meant for them, emphasizing their respective self-interests rather than making proposals for mutually beneficial improvements. Emmanuel Macron diagnosed the ‘brain death of NATO’ as the narrowly self-interested and nationalist stance of the United States undermined France’s trust in the readiness of the United States to defend the alliance. Macron and other European politicians responded with self-seeking demands for institutional alternatives to NATO. Macron stated that the alliance ‘only works if the guarantor of last resort functions as such. I’d argue that we should reassess the reality of what NATO is in the light of the commitment of the United States’ (cited by Economist 2019). Similarly, Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, stated that ‘frankly EU should be grateful. Thanks to him [Trump] we got rid of all illusions. We realize that if you need a helping hand, you will find one at the end of your arm’ (cited by Glasser Reference Glasser2018). Angela Merkel also reflected on how to strengthen alternatives to a US-led NATO since ‘the days where we can unconditionally rely on others are gone’ (cited by Glasser Reference Glasser2018).

In sum, confronted with nationalist-reformist contestation, the defenders of the institution rather ask themselves: ‘What reform is good for me?’ They will tend to respond to the contester’s demands for reform in its parochial national interest with their own self-seeking demands. In a still rather low-key bargain, member states likely emphasize the reforms that suit best their own citizens’ – and not necessarily the mutual – benefit.

Responses to globalist-revisionist contestation: The case of the UNHRC

Globalist-revisionist contestation invites the defenders of an institution to review its purpose, exchanging arguments about its appropriateness. The public exchange of arguments about the institution’s value and fate will likely loom large. Revisionist contestation frames imply maximalist demands from the contesting actor – a fundamental overhaul or the abolishment of the institution. They drive a wedge through contesting and defending member states and contribute to a hardening of the discursive fronts between the contester(s) and defenders of an institution. Revisionist frames constrain the discursive room within which deliberation about reforms can take place. Ceteris paribus, they render a cooperative search for shared solutions more complicated, if not impossible (Kruck and Zangl Reference Kruck and Zangl2020). Defenders will be prompted to respond to revisionist frames in a more confrontational and less conciliatory manner than they would do with reformist frames. Moreover, the polarization between contesters and defenders of the institution incline defenders to take a strong stance to save the institution and reconstitute its legitimacy (Minkus, Deutschmann and Delhey Reference Minkus, Deutschmann and Delhey2019; Panke and Petersohn Reference Panke and Petersohn2016; Squatrito, Lundgren and Sommerer Reference Squatrito, Lundgren and Sommerer2019). Revisionist frames may thus contribute to a ‘rally-around-the-flag effect’ (Mueller Reference Mueller1970) as defenders rush to the rescue of the attacked institution. Revisionist frames suggest mobilization and outspoken responses from other actors defending the institution. Defenders should emphasize their different views about the value of the contested institution and counter-attack the contester.

In line with these expectations, the Trump Administration’s revisionist contestation of the UNHRC was criticised by almost all sides – indicating a ‘rally-around-the flag’ effect. Almost all but the Israeli government criticized the United States for weakening human rights protection and the Council as a multilateral forum to promote them. While many agreed in part with the substantial criticism and affirmed a need for reform, the Trump Administration’s revisionist contestation led to a clear commitment to the UNHRC. For instance, EU member state governments claimed that the EU

remains steadfastly and reliably committed to the Human Rights Council as the United Nations’ main body for upholding human rights and fundamental freedoms worldwide. We reaffirm our support to the effective and efficient functioning of the Human Rights Council and remain committed to cooperating with all countries and with civil society to strengthen the Council, while protecting its achievements. (EEAS 2018)

Similarly, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas emphasized that ‘at a time when other countries are withdrawing from the Council, Germany will stand up for the protection and promotion of human rights across the world’ (cited by Federal Foreign Office 2019). Fighting back against revisionist demands, defenders of the UNHRC strongly criticized the Trump Administration’s withdrawal of commitment to the Council by stating that this ‘risks undermining the role of the US as a champion and supporter of democracy on the world stage’ (EEAS 2018). Along similar lines, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein called the US retrenchment from the Council ‘disappointing’ (cited by UNHRC 2018).

However, compared with nationalist frames, globalist contestation frames still leave some room for responses that stress the desirability and possibility of legitimacy-enhancing reforms of the institution. As the contester purports to care about the interests of other member states, contesters profess their commitment to global values and portray themselves as other-regarding actors too. This invites responses that aim to persuade the contester of an institution’s value and keep them engaged in international cooperation, despite fundamental disagreements. The other-regarding argumentation of globalist contesters facilitates responses that, instead of ‘giving up’ on the contester as responsible multilateral stakeholder, plead with them to reconsider their stance and, in the interest of all, re-engage with the institution.

Indeed, the globalist framing of the Trump Administration’s contestation of the UNHRC was followed by responses which appealed to the United States to rethink its fundamental rejection of the institution for the sake of global human rights. Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein underlined that, given the worldwide state of human rights, ‘the US should be stepping up, not stepping back’ (UNHRC 2018). Western countries such as Germany not only regretted the US withdrawal from the UNHRC under Trump but also welcomed the US reengagement with the UNHRC under President Biden (Blinken Reference Blinken2021).

In sum, globalist-revisionist contestation suggests the defenders of the institution ask themselves: ‘Should we save the institution?’ They will be inclined to review the institution and its purpose, exchanging arguments about their appropriateness and the (il-)legitimacy of radical attacks against the institution. Actors in favor of the status quo are encouraged to make an effort to persuade more sceptical member states – including the contesting state – that the institution is still worthwhile.

Responses to nationalist-revisionist contestation: The case of the WTO

Faced with nationalist-revisionist contestation, defenders are more likely to outright refute the contester’s self-seeking rejection of the institution and vocally appeal to fellow member states to unify behind it and push back against the contesting state. Nationalist-revisionist frames thus predispose the defenders to engage in direct vociferous counteraction to mobilize support for the institution.

With nationalist-revisionist contestation frames, the effects of nationalist and revisionist frames (see above) reinforce each other. Defenders will be inclined to respond to revisionist frames in a more confrontational and less conciliatory manner than they would to reformist frames. Rather than looking for common ground, they should emphasize their conflicting views about the value of the contested institution. The nationalist, overtly self-seeking framing further contributes to hardening polarized stances and shrinking the space for compromise, even compared with globalist-revisionist frames. Nationalist-revisionist contestation frames are thus likely to provoke strong resistance by defenders. As hardly any common ground is shared by contesting and defending actors, re-legitimation attempts that aim at engaging with the contester to find agreement are discouraged. Rather, defenders may seek to build and stir up coalitions to push back against the contester. We expect to see frequent, prominent and unequivocal expressions of defenders’ commitments. Moreover, and in contrast to responses to globalist(-revisionist) frames, nationalist-revisionist contestation facilitates shaming of the narrowly self-interested contesting actor and unification appeals to other states to unambiguously back up the attacked institution and remain steadfast in their support (see Panke and Petersohn Reference Panke and Petersohn2016; Minkus, Deutschmann and Delhey Reference Minkus, Deutschmann and Delhey2019; Squatrito, Lundgren and Sommerer Reference Squatrito, Lundgren and Sommerer2019).

The numerous and strong responses to the WTO’s contestation confirm these expectations: China, the EU and South American states jumped to the institution’s defence with calls to strengthen rather than weaken the multilateral trading system: ‘The problems of the WTO can only be resolved with more WTO not less WTO’ (Argentine’s president Mauricio Macri, cited by Donnan and Mander Reference Donnan and Mander2017). The Trump Administration’s nationalist-revisionist contestation prompted other powers, such as the EU, to respond as ‘system-preserving power[s], leading efforts to defend the established order’ (Hopewell Reference Hopewell2021: 1025). Moreover, and in contrast to the more moderate, pleading responses to the globalist-reformist contestation of the UNHRC, the obviously self-interested criticism of the WTO by the Trump Administration made it easy for (proclaimed) defenders of the WTO to denounce and shame the US attack as being driven by mere parochial egoism.

Accordingly, Huo Jianguo, a former trade negotiator for China and now vice chairman of the state-run think tank China Society for WTO Studies, responded to US rejection of rules-based dispute settlement: ‘We must expose in this the narrow-minded intentions of the U.S.’ (cited by Chiun-Wei Yap Reference Chiun-Wei2021). Argentine’s president Mauricio Macri criticized the United States for turning away from multilateral trade cooperation to pursue the ‘primacy of national interest’ (cited by Donnan and Mander Reference Donnan and Mander2017). WTO Deputy Director-General Alan Wolff also pushed back against the Trump Administration’s criticism: ‘Whether the shock and awe of Trump Administration trade policy can be channeled into making the trading system better is an open question’ (WTO 2018).

Finally, we also found unification appeals to other states to close the ranks and continue supporting the WTO. Chinese officials pointed out that a US withdrawal from the WTO ‘might not be a bad thing, because it [the US] has constantly undermined the WTO and made it impossible for anything to get done … The WTO has 164 members, and the US is just one’ (He Weiwen, state-controlled China Society for WTO Studies, cited by Wang Cong Reference Cong2020). ‘Without the US, the WTO could operate even better … We shouldn’t view the US as anything more than just a country’ (Mei Xinyu, Ministry of Commerce, cited by Wang Cong Reference Cong2020). A joint statement of the EU, China and several other states reaffirmed their commitment to multilateral dispute settlement: ‘We believe that a functioning dispute settlement system of the WTO is of the utmost importance for a rules-based trading system, and that an independent and impartial appeal stage must continue to be one of its essential features’ (European Commission 2020). Along similar lines, WTO Director-General Roberto Azevedo responded to the Trump Administration’s criticism of the WTO’s dispute settlement body that this did ‘not mean the end of the multilateral trading system’ (cited by Swanson Reference Swanson2019).

In sum, nationalist-revisionist contestation suggests the defenders of the institution ask themselves: ‘Can we save the institution?’ It invites strong expressions of commitment to the valued institution and stark criticism of the contester by defenders. Defenders are called upon to refute the self-seeking rejection of the institution by the contesting state and appeal to other member states to unify behind the institution. Their arguments in favour of the institution will likely be frequent and public debate will be rather high-profile.

V. Conclusion

By conceptualizing four types of institutional contestation frames, this article contributes to a more nuanced grasp of the contestation of international institutions by established Western powers. Differentiating between globalist-reformist, nationalist-reformist, globalist-revisionist and nationalist-revisionist frames matters for the targeted institution’s legitimacy. Our analysis of the Trump Administration’s contestation of the World Bank, NATO, the UNHRC and the WTO demonstrates that contestation frames employed by the same government can vary considerably. It further shows that the responses by defenders of the four institutions varied in line with our expectations.

Our aim in this article was primarily conceptual and theoretical. The four case studies served illustrative purposes and do not allow for strong claims of generalizability. Still, the fact that we observe all four contestation frames by the same administration lends initial confidence to our conceptualization. Moreover, the fact that alternative explanations cannot account for the observed variation in the re-legitimation responses lends some initial confidence to our theoretical argument. One might argue that the variation in re-legitimation responses stems from other member states’ varying socialization in the institution. We should thus expect that the older an institution is, the stronger its defence will be. If this were true, the strength of re-legitimation responses should increase from the UNHRC (created in 2006) over the WTO (created in 1995) and NATO (created in 1949) to the World Bank (created in 1944). This is not what we see. Moreover, one might also argue that the individual benefits from an institution drive re-legitimation responses. The strength of re-legitimation responses should thus be a function of the material benefits an institution provides to its member states. If this expectation held, the strength of re-legitimation response should be considerably stronger in the cases of the World Bank, WTO and NATO, which provide economic or security benefits to their members, compared with the UNHRC, which does not provide any material benefits to its members. Again, this is not what we see. While our article thus provides some initial indications for the usefulness of our conceptual and theoretical arguments, they still need to be systematically validated in other cases beyond contestation by the Trump Administration and beyond the core institutions of the LIO.

This article facilitates future research along three lines of questioning. First, future research could use our typology as a springboard to map institutional contestation frames across actors and time. Which contestation frames prevail in the rhetoric of different actors? How have contestation frames employed by particular states changed over time? Do we see processes of ‘(de-)radicalization’ in contesting actors’ criticism of international institutions? Do the contestation frames employed by other contesting actors, such as rising powers and civil society actors, differ from those employed by established Western powers?

Second, while explaining the use of different frames is not the focus of this article, future research could unpack the drivers of varying contestation frames. Different audiences might lend themselves to different contestation frames. Specifically, whether governments aim to target primarily a domestic or an international audience might affect their choice between nationalist or globalist frames. Similarly, pre-existing legitimacy beliefs in an institution and its underlying (liberal) principles might condition the use of reformist or revisionist contestation frames (Börzel and Zürn Reference Börzel and Zürn2021; Sandholtz Reference Sandholtz2019). The substantive issue addressed by an international institution might also affect the frames with which it is contested. For instance, whether an issue can be framed as related to ‘national sovereignty’, such as security, or social and humanitarian issue, such as development, might impact whether contestation is nationalist or globalist.

Finally, future research could further examine the implications of different contestation frames. Our findings lend plausibility to the argument that different contestation frames affect the response by the defenders of the targeted institution. Future research could systematically probe our claim that, ceteris paribus, different contestation frames are associated with different opportunities for the re-legitimation of contested institutions and study how these discursive opportunities interact with other factors – such as socialization in, or benefits from, contested institutions. Moreover, as we did not assess the ultimate effect of defenders’ responses on the targeted institution’s legitimacy, future studies could analyse the role different re-legitimation discourses play for different audiences’ legitimacy beliefs about the institution and how these in turn translate into institutional outcomes, such as reform, abolishment, or counter-institutionalization (Daßler, Heinkelmann-Wild and Kruck Reference Daßler, Heinkelmann-Wild and Kruck2022).

These important questions highlight our key message that it is not only global civil society actors and rising powers that contest the existing international order; institutional contestation and destabilization of the LIO also stem from Western established powers. We should not simply brush over the differences in institutional contestation by established Western powers. Their critique of international institutions is expressed in globalist-reformist, nationalist-reformist, globalist-revisionist or nationalist-revisionist frames, and this variation matters conceptually, theoretically and in a practical political sense. Taking this variation seriously also enables more nuanced and differentiated assessments of the extent and possible trajectories of the current legitimacy crisis of the LIO. Different contestation frames and the responses they might provoke can shape the evolution of the LIO’s legitimacy in very different directions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Editors of Global Constitutionalism, the three anonymous reviewers and the participants in the workshop ‘The Legitimation of International Organisations in Disruptive Times’ at the 2021 ECPR Joint Sessions. We are particularly grateful to Laura von Allwörden, Tobias Lenz, Michal Parizek, Henning Schmidtke and Kilian Spandler for their valuable comments on previous versions of this article. We would also like to thank Aliaa Aly, Helena Borst and Nadia el Ghali for their excellent research assistance.