To the Editor—The main mode of transmission of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is via droplets, Reference Gandhi, Lynch and del Rio1 and to prevent droplet transmission, universal mask wearing has been advised for healthcare workers and those in the community. 2,3 Transmission other than droplet transmission have also been suggested, although evidence is limited. Reference Klompas, Baker and Griesbach4 We observed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients who were less likely to be infected via droplet transmission through outbreak investigation of COVID-19 in healthcare settings.

Between November 20, 2020, and February 22, 2021, 7 hospitals in 3 cities in Japan experienced outbreaks of COVID-19. In these institutions, 9 healthcare workers were diagnosed with COVID-19. They were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR or antigen test at a local public health laboratory or at the hospital.

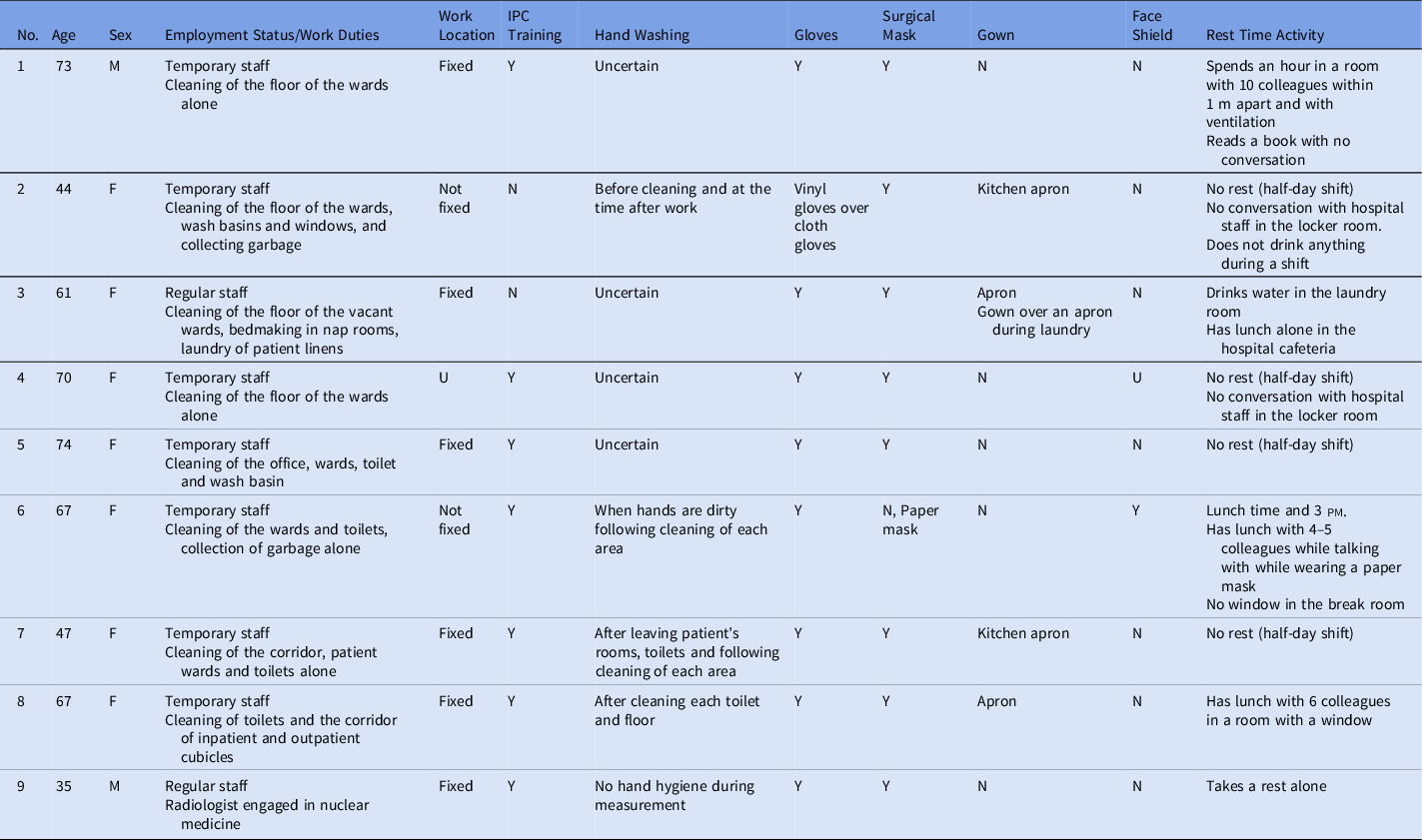

The 9 cases included 7 females (78%), and their overall median age was 67 years (interquartile range [IQR], 35–74) (Table 1). Among these 9 cases, 7 were temporary staff (78%). All of them reported no contacts with other symptomatic people nor groups in their private time in the past 14 days before symptom onset. Notably, 8 of these cases were cleaning staff, and 1 was a radiologist engaged in radiation measurement of the garbage collected from the wards containing suspected COVID-19 cases. None of the subjects had entered COVID-19 wards. Only 1 case entered the ward where an intubated patient without COVID-19 was managed, and none of the others entered wards with patients who underwent aerosol-producing procedures. 5 One case of cleaning staff collected garbage from each patient’s room, but she denied talking to patients. All other cases denied talking with COVID-19 cases and other ill patients. Four cases did not take rest breaks including at lunch time (44%), but the other 5 cases had a rest break every work day. Of these 5 cases, 1 had talked with his colleagues during the break. Hand hygiene status during work was uncertain in 4 cases. The radiologist did not use alcohol-based hand rubs nor wash hands during measurements. During work, 8 cases wore a surgical mask (89%) and 1 wore a paper mask while working. Also, 5 cases did not wear a gown (56%) and the other 4 cases wore an apron; only 1 wore a face shield (11%). Personal protective equipment (PPE) was provided for these workers by outsourcing companies but was not adequate and alcohol-based hand rubs were not provided. Thus, some of them bought PPE for themselves, such as eye protection. They had limited opportunities for infection prevention and control (IPC) training. Information about the COVID-19 outbreak was not provided for them in a timely manner.

Table 1. Summary of the Nine Cases of COVID-19 possibly infected via contact transmission

In this is a case series, workers with COVID-19 did not have a clear history of direct contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases in this healthcare setting during outbreaks. It was less likely that the cases were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the community because the incidence of COVID-19 in the cities was low (˜1–8 cases per 100,000 population per day) and they were mainly the elderly who denied going out after work and in weekends. We identified 3 possible transmission routes for these cases: indirect contact transmission, transmission via conjunctivae, and airborne transmission. Indirect contact transmission is highly likely because all but 1 case wore medical masks during their work; they frequently touched contaminated surfaces in their daily work; their levels of hand hygiene were suboptimal; and SARS-CoV-2 can be infectious on environmental surfaces for as long as 3 days. Reference van Doremalen, Bushmaker and Morris6 Direct contact or droplet transmission via conjunctivae is also possible because 8 orf these 9 cases did not wear eye protection; Reference Chu, Akl and Duda7 however, the case infected via conjunctivae has not been reported so far and it is a theoretical possibility. The other possible route of transmission was airborne. Reference Samet, Prather and Benjamin8,Reference Katelaris, Wells and Clark9 However, none of these 9 cases had entered the COVID-19 wards, and only 1 had entered the wards where patients were receiving aerosol-generating procedures for only a short time. Thus, it is not likely that they were infected through airborne transmission.

This report also highlights the importance of IPC training for temporary staff in healthcare settings. One study reported that hospital cleaning staff have a higher rate of seropositivity (12 of 96, 6%) compared to other professions. Reference Alkurt, Murt and Aydin10 Most of the study participants had received basic IPC training at least once, but none had received COVID-19–specific IPC training. Information about COVID-19 including the disease itself, preventive measures, and the outbreak situation was not shared frequently, and adequate PPE was not provided for these workers. In many healthcare facilities, the temporary staff are often neglected population in terms of IPC training; however, they are also at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. COVID-19–specific IPC training for temporary staff is needed in every hospital and facility not only to prevent their infection but also to guarantee the prevention of the spread of disease by these workers.

Our study has several limitations. First, we could not test environmental samples for each event. Second, there was possible recall bias for contact within 2 weeks before symptom onset. However, most of the participants were elderly people who were unlikely to have had an enjoyable personal life after work during the national state of emergency. Third, this finding was based on the wild-type variant circulating before February 2021 in Japan and may not reflect the transmissibility of other variants.

In summary, contact transmission of SARS-CoV-2 can occur among healthcare workers including temporary staff, and they need to be trained to strictly implement hand hygiene and to use appropriate PPEs for SARS-CoV-2, including eye protection.

Acknowledgments

We thank the infection prevention and control specialists at each hospital, public health officers at the local public health center, and officers at the responsible local governments. We also thank the laboratory staff at the local public health laboratories who conducted RT-PCR.

Financial support

This study was funded by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (grant no. 20CA2036).

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.