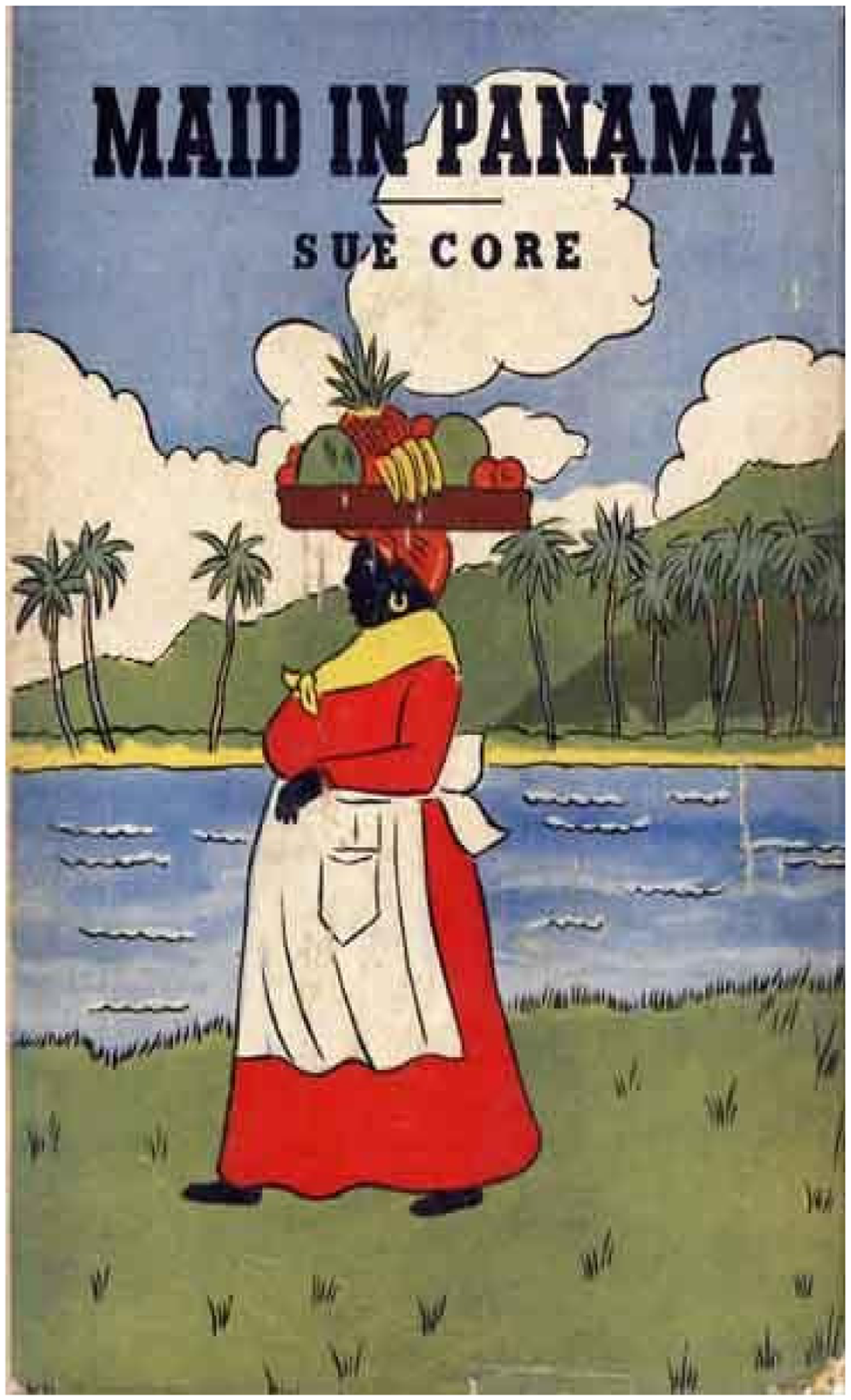

The cover of Maid in Panama depicts a West Indian higgler as a “mammy.” Her skin is an exaggerated ink-black, her body is large, her face round, and she wears a servant's uniform, including headscarf and apron. The higgler walks across an open field carrying a tray of tropical fruits on her head, with a background of palm trees, a placid river, and fluffy clouds.

The higgler on this cover introduces a 1938 edited collection of short memoirs by white Americans, primarily white women, reminiscing about their Black workers and servants during the Canal construction era. During this decade, from 1904 to 1914, Black women from the West Indies provided the domestic and intimate labor that sustained the American imperial colonization of the area under US sovereignty, called the Panama Canal Zone. Their labor in homes, river laundries, and kitchens took place beyond the purview of the Canal administration and mostly went unremarked in official sources, but their consistent presence in memoirs like Maid in Panama belies their importance to Canal Zone society.

Their portrayal in these memoirs, however, obscures as much as it reveals. Memoirs by white American women remain one of the few sources that speak at length about Black women's labor in the Canal Zone. In their recollections, white women are overwhelmingly concerned with the Black women who work for them, from their maids to the local higglers and laundresses of the area. These memoirs privilege the perspectives of white women, who frequently insult and misunderstand the Black women around them. The authors associate Black women with racial and sexual excess, uncleanliness, and barbarism. They rhetorically attempt to put Black women “in their place” by ridiculing and denigrating their labor, relegating them to an inferior status.Footnote 1

In the Canal Zone, the higgler as cartoonish mammy romanticized Black female workers as primitive, uncorrupted beings. Scholars of the US South have argued that the mammy served as a nostalgic fiction that erased the violence of the slave system, hiding it underneath the veil of a happy slave.Footnote 2 As in the South, Black women in the Panama Canal Zone served as a central symbol of imperial nostalgia, romanticizing the “happy” relationship between Black workers and white American employers in this enclave.Footnote 3 The higgler-mammy effaced Black women's work and Americans’ dependence on it. Though ostensibly a tribute to Black “mammies” and maids, memoirs like Maid in Panama rather serve to cement and justify Black women's inferior position in the Canal Zone, naturalizing their role as servants. The mammy then provided visual proof of the need for the “civilizing influence” that white Americans provided to their “backwards” servants during the construction era.

Figure 1. Cover, Sue Pearl Core, Maid in Panama (Dobbs Ferry, 1938) [This item is a work of the US federal government and not subject to copyright pursuant to 17 U.S.C. §105, Courtesy of the University of Florida's Digital Library of the Caribbean]

Yet white women's attempts at dictating Black women's experiences in the Canal Zone unwittingly provide a record of how Black women transgressed and rejected their employers’ standards of civility and “proper” labor. Reading these memoirs against the grain, Black women emerge not as compliant servants and satisfied “mammies” but as mediators and entrepreneurs, negotiating their relationship with their bosses to receive better pay, assert their sexual autonomy, and control the conditions of their labor. I argue that while white women upheld fictions of Panama as a wild domestic frontier to control their maids’ movement and sustain white American supremacy in the Canal Zone, West Indian women rejected these impositions. Instead, they asserted their occupational mobility and economic self-determination by developing their own businesses networks and using a repertoire of entrepreneurial practices they had brought from the West Indies and adapted to their situation in Panama. I show not only how US empire in Panama came into being through white women's domesticity, but also how Black women sidestepped white women's authority and carved out autonomous realms of labor.

Though American memoirists emphasized the narrative of the domestic sphere as a racialized frontier that they tamed, West Indian women in these stories consistently rejected the colonization of their time, independence, and bodies. The hidden subversions of West Indian women problematize the nostalgic, nationalist spaces these American women disseminated in their memoirs. They show how understandings about race, gender, and nation in Panama were in fact produced through labor relations between Black female workers and white female bosses in the context of a growing transnational migratory labor economy. Moreover, this article shows that West Indian women's labor extended far beyond the limited scope of the American home that white women represented in their memoirs. Instead, West Indian women often worked as semi-independent contractors or independent businesswomen, defining their own economic landscapes.

In the decade of the Canal construction, approximately 150,000 West Indian immigrants supplied the bulk of the labor on and off the Canal as part of the segregated “Silver” workforce.Footnote 4 The term “Silver” denotes the common designation for Black laborers in the Canal Zone, who were paid in silver coin rather than in the gold white Americas received, and who faced strict racial segregation in housing, cafeterias, commissaries, and recreational facilities. Historians have attended to the experience of Black male “Silver” workers, who labored under contracts for the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC).Footnote 5 They have given much less attention to the Black West Indian women who also traveled to Panama and provided the essential domestic and intimate labor that sustained the construction project.Footnote 6

Historian Lara Putnam decried how the continued assumption of Black men's predominance in early twentieth century Caribbean migration “has distorted the breadth of Caribbean historical experience” and silenced Caribbean women's experiences.Footnote 7 It has distorted, as well, our understanding of large-scale imperial projects, which solidify as struggles between a fully-formed imperial administration and their contracted male laborers. Looking at West Indian women during this period turns our focus away from the desires of empire, the boundaries of the nation-state, and the narrowness of patriarchal Caribbean mythographies.Footnote 8 This article instead elucidates the US empire as an “on the ground” cultural process and shines a light on women who often skirted US imperial oversight.

White American women in the Canal Zone, as in other contexts, were not bystanders to the project of imperialism, but rather played an active role in maintaining its structures of power and racialized hierarchy.Footnote 9 Some attention has been paid to white American women in the Zone, and scholars argue that they were key in importing “middle-class values” to the Zone, and that they “defined their identity through the distinctions they discerned between themselves and those who served them.”Footnote 10 This scholarship has been scant and overwhelmingly focused on the white women themselves, not taking into account the historical context of their writings nor the presence of Black women in their narratives. While the relationship between Black working women and white female bosses lies at the center of this article, my work focuses primarily on how Black women resisted the impositions of their bosses. Following the work of Thavolia Glymph, this article is more interested in reading the “hidden transcripts” of Black women's resistance and negotiation.Footnote 11

The article further highlights the Canal Zone American household as a site of converging experiences, where women from islands colonized by the British and French met the wives of US imperial workers and bureaucrats, each learning how to navigate this new “contact zone.”Footnote 12 Here, the “freedom dreams” of Afro-Caribbean immigrants escaping the drudgery of plantation labor and colonial surveillance clashed with US visions of anti-Blackness and imperial expansion.Footnote 13 Coming from majority-Black islands, the Zone presented a new racial landscape for West Indian migrants, who had likely never encountered “American-style” discrimination. White American women, some with no prior experience having household help, learned of their role in the “conquest of the tropics” through their interactions with their West Indian maids.Footnote 14 Their joint experience in the Canal Zone home cemented these racial and gendered categories.

Since the 1970s, Latin American and Caribbean historians have expanded notions of labor, exploring women's political participation, their negotiation of work and family life, and the construction of gendered categories of work.Footnote 15 Yet these histories still neglect the realm of domestic and reproductive work in favor of more centrally organized labor.Footnote 16 The Black West Indian women in this article did not engage in overtly political action or organize as workers during this period; they did not strike, or make legal claims on their bosses. However, this does not make their resistance any less of a political statement against the impositions of their bosses. As Stephanie Camp has argued regarding enslaved women's resistance in the plantation American South, though these “everyday forms of resistance” could be seen as merely individual expressions, their outsize importance in their bosses’ accounts confirm their centrality to both bosses’ and workers’ interpretations of their labor and the workspace.Footnote 17

Working in the Canal Zone

The official records of the Canal administration rarely recorded West Indian women's presence or labor. The available data, though incomplete, nevertheless contextualizes their association with the field of domestic labor. More importantly, the data's inadequacies highlight the importance of looking beyond the statistical records to understand the centrality of West Indian women's labor to the everyday operations of Canal Zone society and the women's own relationship to their work. West Indian women often migrated and worked beyond the scope of US imperial authority—a dynamic that silenced their contributions, but also created an opening for their relative autonomy as workers.

The 1912 US Census of the Canal lists that, out of 71, 682 residents:

The census only counts the men and women who lived inside the Canal Zone or worked for the Isthmian Canal Commission while living in Panamanian territory. Most West Indian women likely did neither. The census does not provide a full picture of Black women's presence in Panama and the Zone, but it highlights some important demographic circumstances.Footnote 19 Black women were by far the most populated racial group of women in the Canal Zone. They outnumbered white women two to one. They were also far more likely to be workers. The census counted 3,274 West Indian women from Barbados, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Martinique, Grenada, and other islands as workers.Footnote 20 Meanwhile, according to the census, only 285 American women worked in the Canal Zone.Footnote 21

The most common category of labor for women was in domestic service. The census lists 3,206 foreign-born women as “Laborers, Domestics, etc. (not employed by the Isthmian Canal Commission or Panama Railroad).” Eighty percent of these domestic servants were West Indian, with a handful of native Panama women.Footnote 22 This demographic concentration hints as to why residents of the Canal Zone associated West Indian women with this trade. However, the number inevitably underestimates the number of Black women actually at work in the Canal Zone—of all the Black women residents in the Zone, the census only accounts for 47 percent as employed at all. The census did not include the many West Indian women who did temporary and piece work in American households, providing cooking, cleaning, and laundry to several families during flexible hours, nor the women who walked across Zone towns bringing food to workers and residents. Some West Indian women did indeed work for the Canal Commission, as hired laundresses or cleaning staff in hospitals and hotels, or as teachers for the segregated “Silver” schools that serviced West Indian children.Footnote 23 These positions were relatively few—the great majority of West Indian immigrant women worked in private domestic service and were not individually recorded as Commission employees.

The all-encompassing term of “West Indian” masks these women's different origins from across British and French West Indian islands, each with its own unique historical circumstances, legislation, and established routes of migration. Migrants traveled with their own prejudices toward West Indians from other islands—divisions exacerbated by differences in language, class, and skill level. However, the great majority of West Indian women in the Zone—60 percent—came from Barbados and Jamaica.Footnote 24 White Americans also repeatedly expressed a preference for English-speaking servants, further explaining their predominance in these narratives. But while these regional differences proved occasionally significant, they were far less present in the eyes of white American bosses, who mostly referred to domestic servants as Black, “negro,” or “colored.”

Unlike with Black women, the Commission actively encouraged white women's migration. They paid for white women's passage to the Zone. They provided free married housing and furniture in spacious, suburban homes. They built a female ward in Commission hospitals.Footnote 25 They fostered recreational activities, employing Helen Varick Boswell of New York to build a network of women's clubs throughout the Canal. They eventually expanded the offerings of Zone commissaries to encourage women's consumption by offering linens, hats, fabrics, and other luxury goods alongside food. One journalist even remarked, “it would take another article to relate the rhapsodies of the Zone women over the prices at which they can buy Boulton tableware, Irish linen, Swiss and Scandinavian delicatessen, and French products of all sorts.”Footnote 26 With each of these incentives, the Commission reinforced their commitment to white women's colonization of the Canal Zone. These same benefits were not extended to Black West Indian women.

Maintaining an American household in Panama required a massive amount of work, and domestic servants, laundresses, and household help were in high demand. They found their jobs by applying directly to American housewives, by word-of-mouth, or through newspaper and posted advertisements, as there was no central recruiting station for this work. Domestic servants in the Canal Zone not only had to cook, clean, wash, and perform childcare, they had to do this in an environment of incessant rain, mud, and dust from dynamite blasts, among rampant ants and bugs that proliferated in the humid climate, and with a limited or difficult to acquire supply of food and basic necessities. The work of a domestic servant in the Zone then was not only constant but required a nimble adaptability to the often-unanticipated domestic disasters that befell them.

Many Black West Indian women provided domestic labor as semi-independent contractors, hiring out their services as laundresses to American housewives and businesses in the Zone. Others sold food, provisions, and small trinkets door-to-door as higglers. West Indian women also combined several jobs—as one woman, Ferdilia Capron put it, “I do any work that comes in handy.”Footnote 27 As many scholars of the Caribbean have shown, Black women's enterprising market activity was not a new phenomenon. In fact, enslaved and free Black women had dominated markets during the period of slavery, from New Orleans to Kingston to Antigua.Footnote 28 As early as the mid-seventeenth century, white shopkeepers and merchants felt threatened by Black women's market dominance and tried to control and criminalize it.Footnote 29 After abolition in the British West Indies, Shauna Sweeney argues, higglers fostered Black economic independence from the plantation economy through their leadership in the market system. Throughout the West Indies, higglers would sell prepared foods like bread, fritters, pepper sauces, cassava, and “grater-cake” for a few farthings, as well as cold beverages and small household items out of their small shops that opened up into well-transited public lanes.Footnote 30 Susan Proudleigh, the title character of De Lisser's 1915 novel about a Jamaican woman's migration to Panama, established and ran a small food stall in Kingston before migrating, “a little shop,” which she “stocked with the things she knew would sell.”Footnote 31

A “good cook” in Jamaica earned only twenty-four shillings a month, or around six dollars.Footnote 32 Meanwhile, maids in the Zone earned approximately twelve to fifteen dollars per month, so moving to Panama could easily mean a doubling in pay. A typical “pick and shovel” man earned ten cents per hour doing backbreaking labor, which, on an average of ten hours a day, would mean approximately $24 to $30 a month.Footnote 33 This means that a West Indian maid could significantly add to a household economy, earning about half a male laborer's income. West Indian laundresses often set their own prices and could reportedly make as much six dollars in one day.Footnote 34 For comparison, a white Gold Roll nurse earned fifty dollars a month.Footnote 35 West Indian women could rarely hope to make “Gold Roll” wages or be hired in equivalent skilled positions. Nevertheless, Panama held good opportunities to increase their income. Though not employed by the Isthmian Canal Commission, a laundress could potentially replicate a white laboring woman's earnings through her work. Their earnings, sent back as remittances to the islands along with men's wages, also contributed to the increased circulation of “Panama Money” and the ensuing transformations in bank usage and Black land ownership in places like Barbados.Footnote 36

In the Canal Zone, migrant Black women utilized these same skills to ensure survival and carve spaces of economic autonomy. They worked as in-house domestic servants, sold prepared food to workers and produce to white American housewives, and hired out their laundry services. Yet migration to Panama also provided some unique benefits—a high and urgent demand for their domestic labor and substantially higher prices and salaries for their services than they could get in the islands. This not only provided the motivation to move, it also created a labor dynamic that held particular advantages for Black women. West Indian women were often able to turn down jobs, quit abruptly when they became pregnant, or find new employment. American women's memoirs display the clashes that arose when white bosses’ assumptions about appropriate labor came into conflict with Black women's own expectations.

The Domestic Frontier

Sue Core's Maid in Panama (1938), Elizabeth Parker's Panama Canal Bride (1955), and Rose Van Hardeveld's Make the Dirt Fly! (1956) narrate the nostalgic memories of white American women who lived in the Canal Zone during the era of construction.Footnote 37 All three narratives evince a deep preoccupation with the presence and labor of Black West Indian women. Black women served as the locus of concern for white American women for two reasons. First, they represented symbols of racial difference within a “feminine” sphere in the male-dominated environment of the Canal Zone. They provided a mirror for white women to work out their gendered and racialized anxieties about how to maintain proper standards of domesticity and femininity in a context where these notions had been thrown into disarray by the challenges of the early years of construction.

Second, Black women's independent labor and successful navigation of the chaotic Canal Zone “frontier” jeopardized the romanticized, coherent narrative of American dominance of Panama in which white women were invested.Footnote 38 By defying American notions of productivity and respectability, Black West Indian women called into question the basis of American sovereignty in the Canal Zone, which depended on the characterization of Black and brown subjects as uncivilized and unable to prosper without American aid. The memoirs find narrative ways to contain the perceived threat of Black West Indian women's difference by casting them as pre-modern. They show how the project of producing racial difference and upholding racial ideology in the Canal Zone depended on white women's practices of domination in the home. Through the rhetorical device of nostalgia, white women saw themselves as pioneers of civilization and Black West Indian women as the problem to be solved.

The stories these white women told relied on emphasizing racial difference and celebrating white American's technical dominance over their perceived “uncivilized” servants. Yet, as Tara McPherson says about America's relationship to the South, the Panama Canal Zone of the construction period is “as much a fiction, a story we tell and are told, as it is a fixed geographic space.”Footnote 39 The memoirs were all published decades after the Canal's completion. The authors’ concern with the presence and mobility of their West Indian servants betrays a deep anxiety about the political changes of the post-construction period and the ambiguous triumph of the Canal enterprise. The memoirs showcase the nostalgic stories these authors told themselves—that they tamed the wild jungle and successfully brought civilization to their backward West Indian domestic workers. They also betray the tenuousness of these fictions.

In the United States, the Canal was widely perceived as an achievement of American technological and military might, and its completion was celebrated in events such as the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915. Growing unrest in Panama after the end of construction called this triumphal narrative into question, disrupting notions of the Canal Zone as an undisputed success. The nostalgic remembrances of the three memoirs emerge out of this tension. The authors used the trope of the “frontier” to reaffirm a coherent narrative of successful conquest by replaying that encounter as one between white and Black women, where white women “civilized” their unwieldy Black servants.

Zonians perceived the post-construction period as an attack on their benevolent project from West Indian workers, the US government, and the Panamanian nationalist movement. On February 24, 1920, almost seventeen thousand West Indian workers organized a walk-off strike protesting the dramatic drop in wages that followed construction. They were propelled by the organizing of the Detroit-based United Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way and Railway Shop Employees and the racial nationalist politics of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).Footnote 40 Though the strike lasted only a week, it brought work to a standstill and pressured Congress to demand an investigation into Canal management. Black West Indian worker organizing would continue throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The economic depression following the completion of the Canal also fostered the growth of political party Acción Comunal in 1923. This group backed the 1931 coup d’état that put Harmodio Arias in power, a representative of the nationalist mestizo middle class. Marixa Lasso argues that it was during the 1930s that a sense of national identity arose in Panama through a combination of anti-imperialism and anti-Black racism brought together by nationalist, middle-class politicians as a notion of Panamanian-ness.Footnote 41 Though the Canal Zone was always a contentious and conflicted space, by the 1930s and through the rest of the twentieth century, Zonians faced massive labor strikes, Panamanian nationalist fervor, and a growing hostility toward American imperial presence. In response, Core, Parker, and Van Hardeveld wrote memoirs as nostalgic souvenirs of their “civilizing project,” catalyzed by a felt sense of crisis and criticism.

The massive popularity of frontier nostalgia in the 1950s also powerfully shaped the memoirs. At the time, Westerns dominated publishing, television shows (1955's Gunsmoke), and film (1955's Davy Crockett). By 1959, Westerns accounted for around 24 percent of prime-time programming.Footnote 42 The narratives drew inspiration from the early stories of James Fenimore Cooper and repeated the same tropes of the lone white frontiersman dominating the “noble savage,” usually through superior technology.Footnote 43 These women invested themselves in a feminized version of the frontier narrative, locating themselves on “the home front” in what Parker called “the Battle of the Maids and Houseboys.”Footnote 44 The women saw their interactions with maids as a symbolic struggle of civilization against the encroaching “jungle” of Panama. In their first encounters with Black West Indian women, these authors cast themselves as the lone pioneers with superior intellect and technology and Black women as the “savages” to be dominated.

Rose Van Hardeveld, author of Make the Dirt Fly!, was a Nebraskan homesteader originally born in Alsace-Lorraine. Although Rose was an immigrant to the United States, she portrayed herself repeatedly as an “American woman” and felt kinship with other white women in the Zone. As a homesteader, she would have participated in earlier American colonization efforts throughout the West as a project of bringing “civilization” to an “untamed” territory, asserting white geographical supremacy, and displacing indigenous people.Footnote 45 She moved to Panama in late 1906 to accompany her husband Jan. They lived in House Number One in the married quarters of Las Cascadas with their four children.Footnote 46 Van Hardeveld comments extensively on Black women within the first few pages of her book. On her first outing alone to the commissary shop, Van Hardeveld met two Black women who she referred to as “Fuzzy-Wuzzys,” after a Rudyard Kipling poem: “Two black women in ragged dirty dresses had come in and were jabbering at the Chinese, but he paid no attention to them. I was reminded of Kipling's ‘Here's to you, Fuzzy Wuzzy’ when I glanced at these two black faces with their hair standing up in a stiff fuzzy brush.”Footnote 47 Kipling wrote the poem of the same title in 1892 as a celebration of imperial might. The poem gives sarcastic praise to Sudanese Beja warriors who won a battle during the late nineteenth-century Mahdist War, only to eventually lose the war and come under British imperial control. Van Hardeveled's reference implicitly compared the two Black West Indian women (and thus, herself) to soldiers in a colonial war—one that the Black subjects were bound to lose despite momentary gains. As in the Kipling poem, the primary identifier of the Black “other” was their hair of “stiff, fuzzy brush.”

It turned out, however, that the “jabbering” Black women were multilingual, and helped the newly-arrived Van Hardeveld negotiate with the Chinese commissary salesperson, who only spoke Spanish. They served as intermediaries and translators, showing their competence in the face of Van Hardeveld's inexperience.Footnote 48 It was precisely this that compelled Van Hardeveld to characterize the two women as losing warriors in a colonial war. Van Hardeveld saw the women's easy understanding of the rules and customs of Panama and her own reliance on them as a threat to her natural authority. To call them “Fuzzy-Wuzzys” reset the stage for Van Hardeveld. She placed the women as the Beja warriors and herself as the representative of the empire meant to eventually win the war for dominance. Van Hardeveld continued to rhetorically assert her supremacy by referring to most other Black women throughout the memoir as “Fuzzy-Wuzzys.” Though she manifested anti-Black racism repeatedly throughout the memoir, she saved particular distaste for Black women, such as the one who often sat near the local cantina, about whom Van Hardeveld said, “She reminded me of a fat spider waiting for someone to devour. She often smiled and nodded at me in a friendly way, but I hated her.”Footnote 49

Both the women at the commissary and the woman at the cantina occupied spaces that epitomized the Canal Zone as a “contact zone” of clashing encounters defined by asymmetrical relations of power and miscomprehension, translation, and heterogeneity.Footnote 50 Van Hardeveld was particularly compelled to establish the inferiority of the Black women she encountered in interstitial, public spaces where she (and the Isthmian Canal Commission as a whole) lacked overwhelming power. The commissary, staffed by a Chinese man who spoke no English, and the cantina, typically a gathering space for workers and women looking for entertainment, drinking, and sex, were spaces that threatened the idea of a cohesive, homogeneous space contained by the laws and morality of the Canal Zone. Van Hardeveld saw Black women, who so easily traversed these spaces, as enemies, even when they offered their knowledge to her.

Elizabeth Kittredge Parker's memoir contains less overtly imperialistic tones, but she similarly positioned Black women as ignorant workers desperately in need of training by white women. Parker, the “Panama Canal Bride,” was a recent Wellesley grad from Dover, Maine. She arrived in the Canal Zone on February 13, 1907, following her fiancé, Charlie, whom she married on the day of her arrival.Footnote 51 Parker met her first maid soon after her arrival, during her wedding breakfast:

As we sat down to our wedding breakfast, I was aware of more contrasts—the long table on the narrow screened porch, thick white china, plated silver, paté de fois gras, champagne, roast turkey,—all served awkwardly by a little Jamaican maid in a gingham dress.Footnote 52

Unlike Van Hardeveld, Parker first met this young Black West Indian woman inside her own newly-established home and immediately after her wedding. Thus, her encounter was less plagued with anxiety than Van Hardeveld's commissary conversation and instead served to reaffirm her dominance of a domestic American space. The extravagant array of furniture, silverware, and food seemed to her one of a whole, with the “awkward” maid as the disparate outsider. The rest of her memoir reiterates this contrast and finds Parker attempting to maintain the “standard” of civilization she presumes stands against the encroaching otherness of West Indians and the Panamanian “jungle.”

Later, Parker relates a conversation with a friend who was trying to find a new maid. Her friend, Kay, says about West Indian women that,

They seem so stupid, but when I tried to do without one, I decided they weren't so dumb after all. We have to realize they've never seen the inside of a civilized home before. They've always cooked on charcoal braziers, washed their clothes in the river, and used gourds for dishes.Footnote 53

Parker and her friend Kay both agreed that West Indian women provided an invaluable service and admit that they had misjudged their maid's skills. However, they also undercut these comments by simultaneously characterizing West Indian women as uncivilized. They associated Black women with nature (gourds, the river), while implicitly positioning themselves as more technologically advanced and masters of the “civilized home.” As in Van Hardveld's encounters, Parker and her friend designated West Indian women as uncivilized precisely in the moments when their dependence on them became most explicit. As Parker later finds out, however, some of these “uncivilized” processes worked better than she had imagined.

Sue Core, the compiler of Maid in Panama, worked as a fifth-grade teacher in Ancon Elementary School in the Canal Zone for thirty-three years, from 1919 until her retirement in May of 1952.Footnote 54 Themes of jungles and frontiers abound in many of her works. Though her works never circulated widely in the United States, her teaching and writing continues to be fondly remembered in ex-Zonian circles, such as the online group “Canal Zone Brats.”Footnote 55 Maid in Panama contains a collection of stories submitted by Canal Zone “old-timers” which relate their experiences with all sorts of Black workers, but primarily domestic servants. It relates humorous anecdotes about the intriguing differences that Americans perceived in their servants, emphasizing at every turn the hierarchy of “civilized” whites to “raw” Black workers, such as in a story titled “The Millinery Art”:

Another trial was the raw, inexperienced household servants who were the best to be had, then; brawny and cheerful, but appallingly ignorant Black women fresh from the bush country of the various island hinterlands from which they had come. Training and teaching them the habits and customs of American households was almost as much a job as the digging of Culebra Cut itself.Footnote 56

By listing white women's trials, the narrator of this story elevated white women's domestic and social labor to that of the men building the Canal. They, even more so than the men, were responsible for rearing the Canal from its “infancy”—the mothers of its civilization. The “infancy” did not just refer to the Canal project, but to the “raw” state of the landscape and the servants, who originated in the “bush country.” The story presents Black women as pre-historical, from a “hinterland” in the infancy of development, and thus requiring training from white American women. As in the memoirs, Black women's “brawn” goes hand in hand with their “ignorance”; their physical appearance again presented as evidence of their lack of civilization and lack of femininity. Nostalgic remembrances like Maid in Panama attempted to fix Black womanhood to natural servitude by positioning Black women as ignorant, inexperienced, and wild. In this representation, Black women were barely considered humans, but rather as animalistic and “fresh from the bush.”

The majority of the stories in Maid in Panama tell short accounts of language mishaps or mistranslations. In eerily similar narratives, a Black maid given an order by her boss humorously fails at her task by misunderstanding a keyword. For example, Mabel the maid, after being asked to “put the flowers in water to keep them fresh,” dunked rose buds face down in a bowl of water, to the great dismay of Mrs. Brown.Footnote 57 These stories suggest the domestic frontier as an area that required intervention because of West Indian maids’ ineptitude. Maids were repeatedly shown as “uncivilized,” unable to use technology, understand “correct” English, or interpret social cues that seemed natural to American housewives. Though they might seem mostly silly or humorous, it is really these stories that center the collection—everyday mishaps between maid and boss provided the “common sense” justification that West Indians were naturally inclined to be subservient and in need of teaching. Moreover, the stories all obscure any force white bosses exerted over Black maids—not a single maid was shown to be reprimanded in the stories for any of their mistakes, as the stories all end before the punishment that likely followed these ostensibly humorous mishaps. Core referred to the relationship between “white boss and colored worker” as one of “mutual exasperated tolerance,” erasing the implied power dynamics by implying symmetry between the two responses. The relationship these authors present is rather one of benevolent maternalism, where white bosses struggle to train childlike and inept Black maids in the frontline of the battle against the dangerous and “disordered” frontier.

Despite Parker's invocation of “houseboys,” her and Van Hardeveld's memoirs rarely refer to male servants. Maid in Panama, on the other hand, does include some stories about male West Indian domestic workers—the odd chauffeur or gardener. These stories follow some of the same beats as the ones about women, such as mocking West Indian speech patterns and using a tone of benevolent condescension.Footnote 58 Nevertheless, that the book is primarily concerned with West Indian women is clear from its cover and title. Though West Indian men sometimes worked in American households, in their nostalgic memoirs, white Americans emphasized the Black West Indian woman as the symbolic figure of a Canal Zone “maid” and mammy. Thus, these writings about empire reinforced a gendered and racialized division of labor—white men managed the digging, white women managed the household; Black men did the digging, Black women worked in the household.

The context of growing unrest in the 1930s and 1940s and the popularity of frontier stories explain the emergence of these various memoirs, but it is the labor relation between white American women and Black West Indian workers that structures the narratives they tell. These authors used the genre of women's memoir to assert their importance alongside men in crafting and perpetuating the project of American progress. To do this, they positioned themselves as frontiers-women, and Black women as the “raw” materials that they dominated discursively and spatially. The stories repeatedly try to contain Black women within white American domestic spaces, where bosses could reiterate their powerful notions of a “superior” Western civilization and their maid's infant-like inferiority. However, the stories also betray white women's deep anxiety about Black women when these workers stepped outside of the boundaries set by their bosses, as this questioned the narratives of successful dominance they sought to perpetuate in their memoirs. As the next section will show, Black women resisted white women's project of containment by taking advantage of the high demand on their labor and their mobility.

“The Battle of the Maids and Houseboys”Footnote 59

Live-in domestic servants had to negotiate a more difficult position than other Black West Indian women working in the Zone. In exchange for guaranteed housing and the semblance of “respectability” and protection that came with working for an American employer, domestic servants faced increased surveillance and a constant demand on their time and labor. They were subject to the whims of their employers and to specific rules about time off, recreation, dress, and behavior. They also had the closest relationship to white American families, assisting them in their everyday lives, seeing their moments of frustration and difficulty, cooking their meals, taking care of their young children.

Scholars have affirmed the role of “everyday forms of resistance,” particularly in the study of slavery, repositioning personal actions, such as working slowly, as an integral and public part of slave insubordination.Footnote 60 Though West Indian maids did not face the same violent repression and abuse that slave women did, their bosses nevertheless denigrated their work and tried to limit their freedom. In response, West Indian women utilized some of these same tactics of resistance, making their bosses’ dependence on them visible and obvious, and rejecting impositions on their mobility by working slowly, expressing their distance, or outright refusing to do certain work. For example, Miriam, one of Van Hardeveld's first maids, “treated us with condescending tolerance.”Footnote 61 She lived within walking distance from her bosses’ house and Van Hardeveld complained that “Miriam, fat and dignified, made the trip in twenty or thirty minutes” where it should have, in her opinion, only taken five.Footnote 62 Miriam rejected her boss's understanding of timeliness, working at her own pace while understanding her work's centrality to the maintenance of her boss's expectations of “civilized” life in Panama.

White American women's memoirs are primarily concerned with domestic servants, as they were the people with whom they had the most intimate contact. Their stories show both this perceived intimacy and the subtle defiance of West Indian women against narratives that positioned them as “one of the family.” For example, Mrs. Morrison's spoke about her first “girl,” Jasmine, a young woman from Barbados, saying that:

What Jasmine knew about the ways of white folks could have been incorporated on the point of a needle without undue crowding. However, be it said to her credit, she was willing. So much so that she became practically one of the family . . .

One of her lady's earliest memories of Jasmine harks back to the first Sunday she was with them. A day or so before, one of her boys had upset a bottle of red ink on the kitchen table, and his mother, having nothing else handy, grabbed a sponge lying near, and mopped it up. The sponge, being brightly crimson, was tossed into the garbage pail. Not to repose there unblossomed and unseen, however. On Sunday morning Mrs. Morrison spied it gaily and triumphantly decorating the hat of Jasmine as she went proudly off to church.Footnote 63

For white American women, managing the household meant keeping some version of “order.” As scholars have described, for the nineteenth-century British imperial context, it meant creating an idea of “order” and maintaining clear boundaries between order and disorder.Footnote 64 Cleaning “is not a negative movement, but a positive effort to organize the environment . . . making it conform to an idea.”Footnote 65 Mrs. Morrison perceived the sponge as a used and dirty item after cleaning up the red spill and sees her disposal of it as a “positive” act of cleaning. Due to Jasmine's “mistaken” assumption that the sponge had other uses, the narrator implicitly characterized her as part of the disorder, an “other” that needed to be organized into the boundaries created by these housewives. Jasmine did not conform to the ideas of order and civilization that her white employer espoused, but instead repurposed Mrs. Morrison's discarded sponge as a fashionable accessory.

The story repeats the myth of domestic servants being “one of the family.”Footnote 66 This phrase obscures power dynamics and positions the domestic servant as an always conditional, unequal member. Jasmine could never gain the benefits of actual family. The phrase here serves not to incorporate Jasmine but to infantilize her, positioning her as an ignorant child-like figure (what she knew could fit “on the point of a needle”). The myth of “the family,” as Anne McClintock has argued, serves to sanction social hierarchy within a presumably organic, ahistorical institution that placed men as patriarchal leaders of naturally subservient women and children.Footnote 67 The image of the family guaranteed “social difference as a category of nature” that could be extended to legitimize exclusions in nationalist and imperialist projects.Footnote 68 In the case of Jasmine, her boss granted her status within the family only by characterizing her as uneducated, ultimately reinforcing that she was only part of the family in the sense that she was a subordinate. The comment merely serves to emphasize that Jasmine was not family, nor privy to its benefits, and that only white Americans had the power to designate others as insiders. Positioning maids as “one of the family” is, like “the frontier,” a tenuous fiction built by white women to maintain the racial hierarchies of the employer-domestic relationship.

The story ends with a hint of jealousy in the narrator's last phrase—though she made fun of Jasmine, it was ultimately Jasmine who proudly and “triumphantly” displayed her new accessory on the way to church while Mrs. Morrison was left in the awkward position of “spying” on her maid. Though seemingly inconsequential, the story implies that American women saw domestic interactions of keeping order, both in terms of cleanliness and in terms of social hierarchy, as supremely important in conquering the Canal Zone. More importantly, it shows how domestic servants like Jasmine endured and confronted these attempts at control, physically rejecting the unspoken laws of cleanliness in the American household and engaging with her own community at church. Miriam, Rose, Jasmine, and other Black women like them worked against fictions of being “one of the family” by refusing to quietly acquiesce to the demands of their bosses, and thus questioning the supposedly natural state of their servitude.

As with other encounters in the memoirs, Mrs. Morrison saw Jasmine's clothing as a particularly significant site of contention. The frequent mentions of Black women's clothing in these memoirs always occur as white women observed Black women at work. Thus, their remarks were always enmeshed with understandings about “proper” behavior and labor. For white women, Black women's often extravagant clothing was proof of their banality, indulgence, and poor economic sense, which also manifested in their labor practices. Van Hardeveld made this connection explicit when discussing the washer-woman she had hired:

She was a Barbadian girl named Princess Brown. She came dressed in a bright pink silk dress with a straw sailor hat pinned to her hair. Without removing any of her finery, or losing any of her dignity, she sat in a chair beside the tub of clothes and began a leisurely rubbing between her hands; although she remained several days, she never accelerated her pace nor finished the tub of clothes.Footnote 69

Van Hardeveld went on to say she promptly fired Princess Brown, though she continued to face the same issues with her “successors,” commenting that “With the whole Isthmus teeming with Black women and girls who should have been glad to obtain work, we could not find one person that was efficient or dependable.”Footnote 70 Van Hardeveld suggested that Black women's exuberant clothing and self-presentation was a result of their laziness and implied a certain underserved pompousness in Princess Brown's demeanor. Van Hardeveld and other white American women thus portrayed Black women as their opposite—vain, whereas white women were Spartan; lazy and slow, whereas white women were hardworking. Princess Brown prioritized maintaining her finery and dignity over completing the laundry work on her bosses’ timeline. Perhaps Princess was unused (or averse) to doing manual labor; perhaps she chafed at Van Hardeveld's expectations; perhaps she merely wanted to look fabulous. Whatever the case may be, the story makes clear that Princess Brown was less than concerned with a white woman's authority over her dress and labor.

White women in the Zone failed to perceive what the elegant dresses and headpieces might have meant to Black West Indian women, materially and symbolically. Rather than deference to the labor hierarchy between Black and white women as the predominant framework of their lives, Black women's exuberant clothing displayed an assertive commitment to public expression. That is, while white Americans tried to discursively and materially contain Black women's movement and expression, these women were instead “able to define their own version of freedom that included self-determination and personal pride” through their clothing purchases and display.Footnote 71 Moreover, they emphatically occupied both public spaces and private American homes, despite attempts to denigrate their existence and discipline their behavior. This was not merely banal consumption and personal ostentatiousness but a representation of Black women's investment in the “rituals of status and self-presentation” that they had brought with them from the islands.Footnote 72 White women's obsession with Black women's clothing further reiterated its importance, at least to their own understandings of their relations with their workers. For white women, their maid's colorful clothes were both a marker of their cultural difference and an affront to the standardized norms of “civilization” the American Canal project tried to promote. But the clothes represented the material fruits of these women's labor, particularly in the early years of the Canal Zone, when fine cloth and dresses were not easily acquired. The rules of consumption during construction instructed white women to be thrifty and resourceful, to “make do” without the fineries of life stateside. Black women instead flaunted colorful, extravagant clothing, while also performing hard labor, defying the easy categorizations of frontier life in which white women were invested.

Higglers and Laundresses as Market Entrepreneurs

Black West Indian women found agency within the racialized labor hierarchy of the Canal Zone and functioned beyond the fictionalized frameworks of subservient nostalgia that white women remembered. The same stories, read from the perspective of Black women's experiences, show how these women used their position as flexible labor to cultivate financial and spatial self-determination. Though the Commission ostensibly provided food and laundry to Canal Zone residents, it was in fact Black West Indian women who filled the gap in the high demand for these services. This labor directly served white Americans, but also provided for West Indian needs. As higglers and laundresses, Black West Indian women engaged in entrepreneurial practices adapted from the islands that fostered commercial and social networks in the Zone beyond the purview of the Canal Commission.

White American women such as Rose Van Hardeveld repeatedly disavowed the labor of West Indian women, arguing that American women did most of the housework themselves “because they could not bear the messy negress around.”Footnote 73 White women were in fact heavily dependent on Black West Indian women's labor. In one instance, for example, Parker despaired about her ruined dinner party after the commissary informed her they were out of leg of lamb. Back in her house, she saw Marie, a Martinican higgler, coming up the path: “Much to my joy, she had a beautiful Spanish mackerel in her basket. Wonderful, I thought. At least, we can have a fish course! Sarah [her maid] could fry fish beautifully. I gave a sigh of relief.” Her dinner party was saved by the provisions and service of two West Indian women.

Higglers or hucksters like Marie appear as crucial interlocutors for these white women, given that they provided many of the daily foods the commissary could not stock and often served as their primary connection to the world outside the American home. Already a common practice in the islands, higglering translated easily to the Canal, where American commissaries struggled to keep up with the demands of the ever-growing towns. Van Hardeveld complained about the difficulty of getting to her local commissary, which was located in the town of Emperador two miles away. Though she could reach it by train, “it meant lagging around in the heat for long hours, and the trip had to be made almost every day.”Footnote 74 Moreover, commissaries, which in the early years refused to import foodstuffs from Panama, offered a very limited supply of food.Footnote 75 Even if Americans made a trip to Panama, “one could buy every possible kind of food, native and domestic,” but only “at terrible prices!”Footnote 76 Meals in the early days often meant very basic canned staples and, even after more commissaries opened throughout the Zone, they were, Van Hardeveld recalled, “not much more than a shed, but gratifyingly accessible to me after these long months of having to travel long distances for food or do without. There were staples and canned goods, including milk, onions and potatoes and once in a great while a few pale shrunken cabbages.”Footnote 77 American women could have traveled or sent their maids to the commissaries early to line up and acquire perishable staples like meat, fish, and vegetables before they inevitably ran out. More likely, they acquired their fresh foods from local higglers.

Higglers traveled through American neighborhoods, selling food to the housewives who would otherwise have had to travel quite far to the commissaries where the range of wares was limited, but they also provided for their own underserved communities. Commissaries were segregated and stocked few of the foods that West Indians enjoyed. Later, in response to protests by West Indian workers, they began importing sweet potatoes, yams, and codfish.Footnote 78 Meanwhile, the mess halls served them three meals a day for nine cents each, but the food was often inedible and the mess hall offered no seats for the workers. According to a food supplier from Omaha, “the only difference I could see between the way they fed those negroes and the way I feed my hogs is that the food was put on a tin plate instead of a trough.”Footnote 79 Amos Clarke, a West Indian Silver roll worker, described the work of higglers as an essential part of his morning routine: “In those days, there were no restaurants. In the morning, two women of color would approach our place of work each one carrying a tray with hot coffee, bread and butter, selling them for ten cents.” Clarke credits two Jamaican women for his sustenance, Mariam Cunningson and Caroline Lowe.Footnote 80 Caroline remained in Panama her whole life and lived to be over one hundred years old.Footnote 81

Unlike the Canal Commission commissaries, higglers had no “official” provider and depended on the produce grown on their small, independent farms, or gathered from trustworthy farm contacts. From her porch, Rose Van Hardeveld could see a West Indian home at the edge of “the jungle” where “wild lemons, oranges, and other luscious fruit, rice and cassava grew in well-cared for profusion around the hut.”Footnote 82 West Indian women like Augusta Dunlop in Pedro Miguel owned land where she grew ackee, breadfruit, guanabana (soursop), mango, papaya, and yucca.Footnote 83 These women continued the tradition of keeping small plots of land and growing foodstuffs to sell, held over from slavery and after emancipation. Unlike white Americans, many of these West Indian women would have been familiar with the produce that grew in the tropics and could recreate their agricultural practices from the islands. Higglers like Mariam Cunningson and Caroline Lowe likely created complex commercial networks in the Canal Zone, using their farms and business relationships to provide an indispensable service.

White women's dependence on Black women's market labor is obvious in another Maid in Panama story.Footnote 84 The author tells of her daily vegetable vendor, an older Jamaican woman she calls “the Hoo-Hoo lady,” due to the energetic cry she gave in the mornings to make her presence known, which sounded “somewhat like the call of a cookoo in the jungle.” As in Van Hardeveld's memoir, the narrator made an easy and naturalized analogy between a West Indian female worker and an animal. Like many West Indian women, the Hoo-Hoo lady held two jobs to support her large family—she sold vegetables “up and down Ancon Blvd. . . . on the days that she doesn't wash clothes for her two or three customers.” The returns from individual items were small, each tomato was ten cents, a small bag of green beans fifteen cents, but they could add up cumulatively.

The narrator noted that, despite the difficulty of her work trekking in the humid tropical weather to different homes carrying a heavy load, Hoo-Hoo always seemed serene because she had become “inured to [the] disappointment” that must have been an everyday part of her job when customers did not buy her products. The story highlights the woman's skill at selling her wares—the narrator even noted that she could not control herself from buying every time the saleswoman came around.Footnote 85 The story was meant to celebrate the Hoo-Hoo lady's commercial prowess, though ultimately traffics in the same stereotypes other white women disseminated about West Indian women—their animalistic nature, their inurement to emotion. However, the scene also reinforces the fact that this West Indian woman worked energetically, that she had a large family whom she supported financially, that she worked multiple jobs and had several steady customers, and that her wares were essential and enticing for white Americans. Rather than the naturalized mammy higgler of the Maid in Panama cover, the story of the Hoo-Hoo lady tells us about a businesswoman who knowingly exploited the market need for her goods by white American residents, carving out notoriety as a local higgler.

Many West Indian women worked independently and contracted out their various services to American housewives. Some women would even ask American clients to provide the start-up costs for their business, as in this story where a housewife describes her first interaction with a new laundress:

Kate, first wash woman I had on the Isthmus, outlined for me during our initial conference, the various purchases I should make to start off our laundress-lady combination. She enumerated soap, starch, blueing, clothes pins, ironing board, iron, washboard and tub. Kate was a particular lady of definite convictions, and gave me careful instructions as to the exact brand of each commodity which she preferred. Wishing to please her, I made careful note in order not to make a mistake in their purchase.Footnote 86

The narrator centered on the importance of the “laundress-lady combination,” a crucial labor relationship in the Panama Canal Zone where steam laundries were uncommon and dirt abounded. White women complained repeatedly about the extreme difficulty of doing laundry. They often characterized the activity as a symbolic cleansing of pristine white clothes and tableware of the “dirt” and uncleanliness of Panama. The narrator recounts the story in a humorous tone, reversing the authority between her and Kate and highlighting the absurdity of the white American “lady” having to do work for the laundress. Yet, she did indeed provide these numerous implements for Kate who then used her employer's capital to set up an independent business in the Canal Zone.

In the early years of construction, the Canal Zone only had one machine-washing facility, in Cristobal. Laundry was collected daily by the district quartermasters and sent back within a week. In 1912, the company reported serving 7,260 employees monthly, so clearly many Zone residents did not rely on the Commission laundry facilities for their needs.Footnote 87 Personal household machines were virtually unheard of at the time, so most laundry had to be done outside without the aid of electricity. Most West Indian women, who contracted with American families, washed clothes in backyards using tubs and soap provided by their bosses. Others, who did not have patrons, did laundry on the river:

One of the familiar sights of this hamlet is the village washing place, a pool near the railroad tracks, formed by the swirling of the water in the Frijolita River at a point where it is turned at right angles to its previous course by the interposition of a bank of clay and rock. The method of washing clothes among the lower-class natives and the West Indians can be observed here.Footnote 88

These river laundries were meeting grounds for the women who would get together to work and pass the time while doing this difficult and monotonous task. These spots indeed became “familiar sights” to Americans, who often remarked on the community of laundresses in the press and their memoirs. Laundry, a seemingly menial task, was essential to the smooth operations of the Canal, from house to hospital to hotel. Yet white women continued to belittle this labor performed by Black women:

Getting our laundry done was another trying problem. On the far bank of the stream, squatted on the rocks, a company of women gathered each day to wash. “The city laundry,” said one of the men jocularly. Here buttons were knocked off clothing with a lavish hand, but never found or sewed on again. I watched this gabbling bunch of black women at their work and decided that our family wash should never go to the city laundry. The clothes were soused in the water, rubbed all over with soap, then placed on a rock, pounded and beaten with a mighty swack-swack. . . .Footnote 89

Rose Van Hardeveld located these river laundries as sites of dirtiness and savagery, sarcastically separating them from white American spaces, but her comment also shows how rivers functioned as social spaces for working West Indian women that white Americans could not penetrate or understand. Black laundresses could work on their own time, among friends, and were free to do as they liked. While their employers attempted to contain their movement and regulate their work inside the American home, they built social networks and carved their own public work spaces in areas Americans perceived as the outskirts. In these corners of swirling water and layered clay, West Indian women gathered and gabbed as they performed this essential service.

At the official Cristobal laundry, prices could range from one cent for washing a collar to five dollars for cleaning and pressing a fancy dress.Footnote 90 West Indian women, not beholden to the laws of the Canal Commission, could and often did charge higher prices for their work. One American man described haggling prices with a Black laundress as a battle with a worthy adversary:

A week on shipboard with a baby produced considerable soiled clothing and the landlady recommended a laundress, who, after counting up to sixty-eight pieces, offered to launder them for twenty-five cents “American money” a piece. I saved her life by leaping quickly in front of my wife, and she finally consented to do the laundering for ten cents gold a piece.Footnote 91

The narrator presents himself as a victim of the laundress’ attempt at taking advantage of a young, white American family, but his story also shows that Black laundresses understood the high demand for their work and knew to haggle for higher prices. This laundress sized up her American clients and asked directly for gold coin (only given to American “gold roll” workers), thus assigning a higher value to her labor and defying the racial income discrimination of the “roll system.”

Working West Indian women faced intense surveillance of their relationship and intimate practices through local Canal Zone ordinances and police investigations.Footnote 92 They also faced habitual judgment from bosses and customers, who felt righteous in pointing out the perceived moral failings of the West Indian women around them. In a suggestive story, a white American woman named Mrs. Phelps urgently needed to get her laundry done and drove to one of the “colored” neighborhoods of the Canal Zone in search of her usual laundress, Angelina. When she walked in, Mrs. Phelps:

. . . found Angelina's room fairly swarming with progeny. Little chocolate-colored pickaninnies of every age and hue stood in wooly-headed curiosity, looking at their mammy's “White Lady” come to call. Among the brood, Mrs. Phelps noted with amazement one little white child about two years old . . . evidently a relic of some white man's disregard for the color line.

Mrs. Phelps saw the child as evidence of immoral interracial sex, or possibly sexual assault. She became taken with the child and demanded that Angelina compliment the “pretty baby,” both calling attention to the child's difference from the other children and implying that the baby was somehow more deserving of praise for its lighter skin. Angelina responded with little enthusiasm. Eventually,

. . . the stolid indifference of her face changed a trifle and she burst out, “Yes'm, he's pretty, all right. But tells you for true, Miz Phelps, I ain't never goin’ to have no more white babies. They shows the dirt too plain!”Footnote 93

Mrs. Phelps repeatedly asked Angelina to make sense of the lighter-skinned child for her, but Angelina did no such thing. She instead refuted Mrs. Phelps’ assessment of the child's beauty, flipping the implied racial hierarchy of her comment. Angelina retorted that it was whiteness, not Blackness, that “shows the dirt.” Along with inverting this racial stereotype, Angelina could have been making a subtle comment on the rape that might have resulted in this pregnancy—the baby showed “the dirt” of Black women's vulnerability and white men's sexual access. Both Angelina and the archive are silent on any instances of rape or sexual assault of Black women by white men in the Canal Zone. Indeed, in the understandings of the Canal Zone laws, Black women could not be raped, since:

it is of course a matter of common knowledge that women of the West Indian class are of a low degree of virtue, and there arises therefore a sort of moral presumption in the majority of cases that there would be no necessity for the use of forceFootnote 94

In this context of sexual vulnerability, Angelina's response parallels what Darlene Clark Hine calls the “culture of dissemblance,” a strategy wherein Black women in the U.S. protected their bodily autonomy by maintaining the semblance of openness, while keeping their intimate lives a secret.Footnote 95 Angelina similarly used humor and irony to sidestep Mrs. Phelps’ intrusion into her sexual history while also calling attention to the violence of rape, and asserting that she “ain't never goin’ to have no more white babies.” Through this rhetorical strategy Angelina laid claim to her own time, space, and erotic agency, and “resist[ed] the misappropriation” of the light-skinned child as a symbol of white beauty.

Whereas live-in domestic workers shared their daily lives with their bosses, most laundresses maintained a separate home life, traveling to American neighborhoods only to work. The “laundress-lady” relationship depended on carefully constructed boundaries. The American housewife clearly held the economic power, but the stories show that most white women behaved with a certain deference toward West Indian women because the service they provided seemed so grueling, yet so necessary. Because laundresses were semi-independent contractors, they had more authority in relation to the American “ladies” than domestic servants. Van Hardeveld commented on what she perceived as laundresses’ arrogance saying, “Washerwomen were asked to clean the kitchen floor after they finished the washing, which seemed to them an outrage.”Footnote 96 In fact, the quote highlights West Indian laundresses’ resistance to their bosses’ additional expectations and demands. West Indian laundresses could and did refuse to do extra work for their customers, along with demanding high prices for their essential labor. Despite living apart from American homes, their spaces could be invaded and criticized by their bosses, as did Mrs. Phelps with Angelina. This they also resisted, sometimes overtly calling out the “dirt” that marked the relationships between white and Black residents of the Canal Zone structured as they were by segregation and criminalization.

Conclusion

Reading these memoirs against the grain chronicles Black West Indian women's diasporic strategies of survival and entrepreneurship against the background of early twentieth century US imperial expansion. West Indian women bore the burden of social reproduction in the Canal Zone, subsidizing the responsibility of the Canal Commission to provide for the residents of the area, particularly for West Indian men who received inferior food and services. Their presence in the American home in the Zone presented a foil for white women to imagine themselves as imperial pioneers, envisioning the imperial encounter as a domestic interaction between boss and servant or the “laundress-lady combination.” But for West Indian women, migration and work in the Canal Zone was not at all understood through a narrative of the “frontier,” of a civilizing project, or of the unruly “jungle.” The Canal construction instead provided them an opportunity to work independently, save money for themselves and their families, and cultivate spaces of social and economic autonomy. These women rarely obeyed the logic of productivity, authority, and respectability that structured Canal Zone society. While limited by the constraints of a racially segregated system, they nevertheless wore colorful and attention-grabbing outfits while performing hard labor, haggled and raised their prices to meet the persistent demands of their clients, performed their work at their own pace, and often chose to leave jobs for other readily available opportunities. Their experience in this imperial enclave recasts the story of the Canal construction as part of West Indian women's long negotiation and enactment of freedom throughout the Americas, disrupting the romanticized symbols of the loyal mammy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors and blind reviewers at International Labor and Working-Class History for their helpful engagement and encouragement. The first version of this article, many years ago, was born as an essay for Sinclair Thompson's “Historical Consciousness in Latin America” class and benefited from his guidance. I also thank Michael Gomez, Barbara Weinstein, Ada Ferrer, Lara Putnam, and Rachel Nolan for reading and commenting on this article in previous stages of its life. Thank you to Jennifer Eaglin for her crucial edits on the last stage of this manuscript.