Article contents

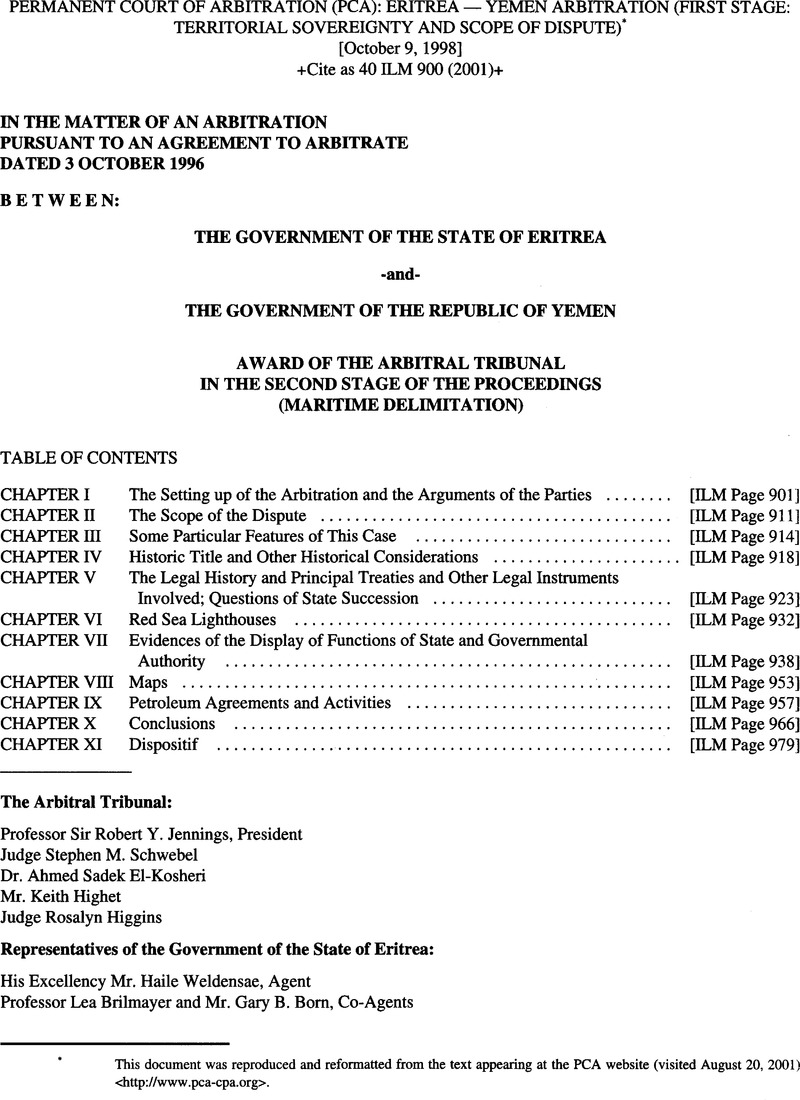

Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA): Eritrea — Yemen Arbitration (First Stage: Territorial Sovereignty and Scope of Dispute)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2001

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the PCA website (visited August 20, 2001) <http://www.pca-cpa.org.>

References

1 The identification of the specific islands or island groups in dispute between the Parties has been entrusted to the Tribunal by Article 2 of the Arbitration Agreement (see para. 7, above), and is dealt with in the part of this Award dealing with the scope of the dispute. References to “the Islands” in this Award are to those Islands that the Tribunal finds are subject to conflicting claims by the Parties. The geographic area in which these islands are found is indicated on the map opposite page 1.

2 Although Eritrea has also submitted cartographic evidence showing the Islands to be Ethiopian, Eritrean or, in any event, not Yemeni, it places relatively little weight on this type of evidence. Eritrea takes the position that maps do not constitute direct evidence of sovereignty or of a chain of title, thereby relegating them to a limited role in resolving these types of disputes.

3 Legal Status of Eastern Greenland (Den. v. Nor.), 1933 P.C.I.J. (Ser. A/B) No. 53.

4 In a letter dated 4 January 1996, Yemen formally protested an Eritrean oil concession to the Andarko Company which, according to Yemen, constituted” a blatant violation of Yemeni sovereignty over its territorial waters in so far as it extends to the exclusive territorial waters of the Yemeni Jabal al-Tayr and al-Zubayr islands, in addition to the violation of the rights of the Republic of Yemen in the Exclusive Economic Zone.“

5 Chile, Argentina v. (9 Dec. 1966), 16 R.I.A.A. 111,115; 381.L.R. 16, 20 (1969).Google Scholar

6 Throughout this award, the date used for the Treaty of Lausanne is its date of signature, in 1923, rather than that of its entry into force (1926).

7 Island of Palmas (Neth. v. U.S.) 2 R.I.A.A. 829 at 867 (Apr. 4, 1928). Professor Max Huber, at the time President of the Permanent Court of International Justice, acted as sole arbitrator in proceedings conducted under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, pursuant to the 1907 Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes.

8 Sir Frederick Pollock, A First Book Of Jurisprudence 177 (6th ed., 1929).

9 See, in particular, John, B Aldry, One Hundred Years of Yemeni History: 1849-1948, in L'arabie Du Sud Vol. II at 85 (J. Chelhod Etal., Eds. 1984)Google Scholar; Roger Joint Daguenet, Histoiredelamerrouge:Delessepsanos Jours, 113-116, 186-190, 240-241(1997).

10 See in this respect, Blum, Yehuda Z., Historic Rights, in 7 Encyclopedia Of Public International Law 120 et seq:, and Historic Titles in International Law 126–129 (1965)Google Scholar

11 See in particular, Charles Forster, The Historical Geography of Arabia, Vol. 1 at 113, Vol. n at 337 (1984) (first published in 1844); Joseph Chelhodetal.,L'Arabiedusud—Histoireet Civilisation, Vol. I, at 63,67-69,252-255 (1984); Roger Joint Daguenet, Histoire De La Mer Rouge: De Moise A Bonaparte 20-24, 86-87 (1995); and Yves Thoraval Et Al., Le Yemen Et La Mer Rouge 14-16,17-20, 35-37,43-47, 51-54 (1995).

12 See in particular, A. Sanhoury, Le Califat, 22,37,119,163,273,320-321 (1926); Kadouri, Majid, Islamic Law, 6 Encyclopedia of Public International Law, 227 Google Scholar et seq.; and Ahmed S. El Kosheri, History of Islamic Law, 7 Encyclopedia Of Public International Law, 222 et seq.

13 Compare the policy objective that was explored by the Foreign Office for the islands of Sheikh Saal, Kamaran, and Farsan, and for Hodeidah, namely occupation. In the event, a 1915 telegram from the Viceroy of India indicates that the British flag had been hoisted on Jabal Zuqar and the Hanish Islands. These events were characterized, in a message to the Foreign Office from the British Resident in Aden as a “temporary annexation.” By 1926 Britain did not regard itself as holding sovereign title.

14 The Treaty of Lausanne, entered into five years after the end of hostilities, in fact uses the term “High Contracting Parties” rather than Allied Powers. Those High Contracting Parties were the British Empire, France, Italy, Japan, Greece, Roumania and the Serb-Croat-Slovene State on the one hand, and Turkey on the other.

15 See Reilly, Aden And Yemen, Colonial Office 1960,69-70.

16 The Dutch had not been signatories to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and had in fact remained neutral in the First World War.

17 The Tribunal notes, however, that prior to Italian occupation, the islands off the African coast were administered by the Khedive of Egypt on behalf of the Ottoman Empire.

18 Nor has Italy or, for that matter, any state asserted that it considers itself to be “a party concerned” for this purpose. The Tribunal therefore concludes that, with respect to the islands in dispute, the only present-day “parties concerned” are the Parties to this arbitration.

19 Eritrea has submitted two translations of this document, one of which refers to “jurisdiction” and the other to “sovereignty.“

20 Map 3 (dated November 1993) shows Area 10 (“Bera'isole“) and Area 11 (“Beilul“), but Area 12 is actually “Assab-Dumeira.“

21 The samples of fishing and boat licenses supplied by Yemen are not helpful; when they specify fishing areas, they only state “Red Sea.“

22 In one example, it appears that the officer of the watch has helpfully added estimated radar ranges of distance, e.g.: “Ø Jabal at Tair Isl. 045 ° 6.0 by radar,” and “Ø Haycock Isl. 106° 15 by radar,” showing that the vessel (H.I.M.S. PC-12) was far offshore on both occasions.

23 According to a witness statement submitted by Yemen,”… any disputant who seeks to avoid an unfavorable decision of the Council may find himself subject to action by the State, including, under certain circumstances, prison.“

24 Fisheries Case (U.K. v. Nor.) 19511.C.J. 116 (Dec. 18) at 133.

25 The Tribunal wishes to note the sheer volume of written pleadings and evidence received from the Parties in this first phase of the arbitral proceedings. Each Party submitted over twenty volumes of documentary annexes, as well as extensive map atlases. In addition, the Tribunal has carefully reviewed the verbatim transcripts of the oral hearings, which together far exceed 1,000 pages. The Tribunal further notes that the majority of documents were submitted in their original language, and the Tribunal has relied on translations provided by the Parties.

26 Minquiers and Ecrehos (U.K. v. Fr.), 19531.C.J. 47.

27 Island of Palmas (U.S. v. Neth.), 2 R.I.A.A. 829 (1929).

28 Legal Status of Eastern Greenland (Den. v. Nor.), 1933 P.C.I.J. (Ser. A/B) No. 53.

29 32 B.Y.I.L. (1955-56) 73-74.

30 D. O'Connell, The International Law Of The Sea 185 (1982).

31 In this connection it is interesting to see the statements made in the 1977 “Top Secret” memorandum of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of The Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, discussed above in para.. This memorandum refers to islands in the southern part of the Red Sea that “have had no recognized owner,” with respect to which Ethiopia “claims jurisdiction” and “both North and South Yemen have started to make claims.“South Yemen's position is that the islands were illegally handed over to Ethiopia by the British when Britain was giving up its rights in the protectorate of Aden.” It adds “the North Yemen government has now raise the question of jurisdiction over the islands. It goes on to recommend bilateral negotiations which seem in fact to have been entered into before the time of this memorandum for it goes on to say that” [b]oth states … have informally mentioned the possibility of dividing the islands between the two of them. The proposal is to use the median line, which divides the Red Sea equally from both countries’ coastal borders, as the dividing line …. Ethiopia rejected this proposal as disadvantageous.“

32 See Bowett, D., The Legal Regime Of Islands In International Law 48 (1978),Google Scholar where he says of islands lying within the territorial sea of a state, “Here the presumption is that the island is under the same sovereignty as the mainland near by;” and he also interestingly Quotes Lindley, The Acquisition And Government Of Backward Territory In International Law 7 (1926), writing, it may be noted, in the mid-1920s that “An uninhabited island within territorial waters is under the dominion of the Sovereign of the adjoining mainland.“

33 Foreign Office Memorandum dated 10 June 1930, prepared by Mr. Orchard.

- 1

- Cited by