No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

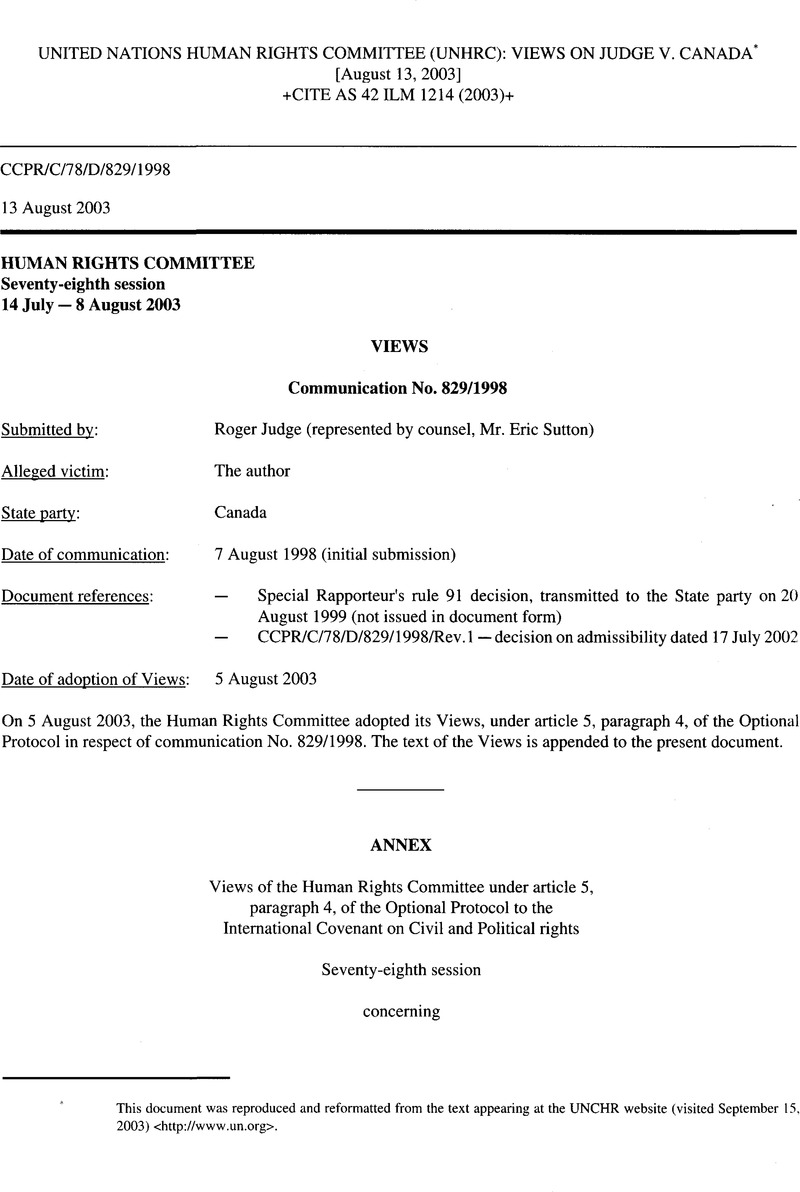

United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC): Views on Judge v. Canada

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2003

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the UNCHR website (visited September 15, 2003) <http://www.un.org>.

References

Endnotes

** The following members of the Committee participated in the examination of the present communication: Mr. Abdelfattah Amor, Mr. Prafullachandra Natwarlal Bhagwati, Mr. Alfredo Castillero Hoyos, Mr. Franco Depasquale, Mr. Maurice Glèlè Ahanhanzo, Mr. Walter Kälin, Mr. Ahmed Tawfik Khalil, Mr. Rajsoomer Lallah, Mr. Rafael Rivas Posada, Sir Nigel Rodley, Mr. Martin Scheinin, Mr. Hipolito Solari Yrigoyen and Mr. Roman Wieruszewski.

Pursuant to rule 85 of the Committee's rules of procedure, Ms. Ruth Wedgwood did not participate in adoption of the views.

1 The author states that the mode of execution was subsequently changed to execution by lethal injection.

2 As later explained by the State party, pursuant to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, a prisoner in Canada is entitled to be released after having served two thirds of his sentence (i.e. the statutory release date). However, the Correctional Services of Canada reviews each case, through the National Parole Board, to determine whether, if released on the statutory release date, there are reasonable grounds to believe that the released prisoner would commit an offence causing death or serious harm. Correctional Services of Canada did so find with respect to the author.

3 As later explained by the State party and evidenced in the documentation provided, the Minister informed the author that there was no provision under sections 49 and 50 of the Immigration Act to defer removal pending receipt of an extradition request or order. However, in the event that an extradition request was received by the Minister of Justice, the removal order would be deferred pursuant to paragraph 50(1 )(a) of the Immigration Act. An extradition request was never received.

4 The State party refers to the following cases Pratt and Morgan v. Jamaica, Communication Nos. 210/1986, 225/1987, Barrett and Sutcliffe v. Jamaica, Communication Nos. 270/1988, 271/1988, Kindler v. Canada, Communication No. 470/1990, Views adopted on 30 July 1993, Johnson v. Jamaica, Communication No. 588/1994 and Francis v. Jamaica, Communication No. 606/1994.

5 The State party refers to Pratt and Morgan, supra, Wallen and Baptiste (No. 2) (1994), 45 W.I.R. 405 at 436 (C.A., Trinidad & Tobago).

6 Kindler, supra.

7 Reid v. Jamaica, Communication No. 250/1987.

8 McTaggart v. Jamaica, Communication No. 749/1997.

9 The State party refers to M. Nowak, U.N. Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: CCPR Commentary (Strasbourg: N.P. Engel, Publisher, 1993) at 266.

10 The State party refers to Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Deemer, 705 A. 2d 627 (Pa. 1997)

11 Pratt and Morgan v. Jamaica, supra.

12 .Kindler v. Canada, supra, Ng v. Canada, Communication No. 469/1991, Views adopted on 5 November 1993, Cox v. Canada, Communication No. 539/1993, Views adopted on 31 October 1994, G.T. v. Australia, Communication No. 706/1996, Views adopted on 4 November 1997.

13 According to the State party, with respect to the conditions under which the death penalty is applied in the State of Pennsylvania, the Committee found in paragraph 7.7 of its decision on admissibility that the author had the right under Pennsylvanian law to a full appeal against his conviction and sentence and that the conviction and sentence were reviewed by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. The Committee held that the author's claim based on article 14, paragraph 5 was inadmissible.

14 HRI/GEN/1/Rev6.

15 The State party refers to Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, U.N. Doc. A/Conf. 39/27 (1969) which states that a “treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in light of its object and purpose.” Article 31 requires that the ordinary meaning of the terms of a provision of the treaty be the primary source for interpreting its meaning. The context of a treaty for the purposes of interpreting its provisions includes any subsequent agreement or practise of states parties that confer an additional meaning to the provision (art. 31, paragraphs 2 and 3).

16 Supra.

17 Supra.

18 Supra.

19 G. T. v Australia, supra.

20 [1991] 2 S.C.R. 779.

21 [1991] 2 S.C.R. 858.

22 Ibid., at page 840.

23 U.N. Doc A/RES/45/116, adopted 14 December 1990.

24 Kindler v. Canada, supra.

25 Kindler v. Canada, supra.

26 The State party refers to Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s. 24(1) which, in a similar manner to the Covenant, protects individuals’ right to “life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice” (s. 7) and the right “not to be subjected to any cruel and unusual treatment or punishment” (s. 12). Anyone who claims that his or her rights or freedoms have been infringed may apply to a competent court to obtain such remedy as the court considers just and appropriate in the circumstances.

32 Supra.

33 [2001] FCT 148 (March 6, 2001).

34 Supra.

35 Supra.

36 Supra.

37 Supra.

38 Communication No. 692/1996, A.R.J. v Australia; No. 706/1996, T. v. Australia; No. 470/1991, Kindler v. Canada; No. 469/1991, Chitat Ng v. Canada and No. 486/1992, Cox v. Canada.