No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

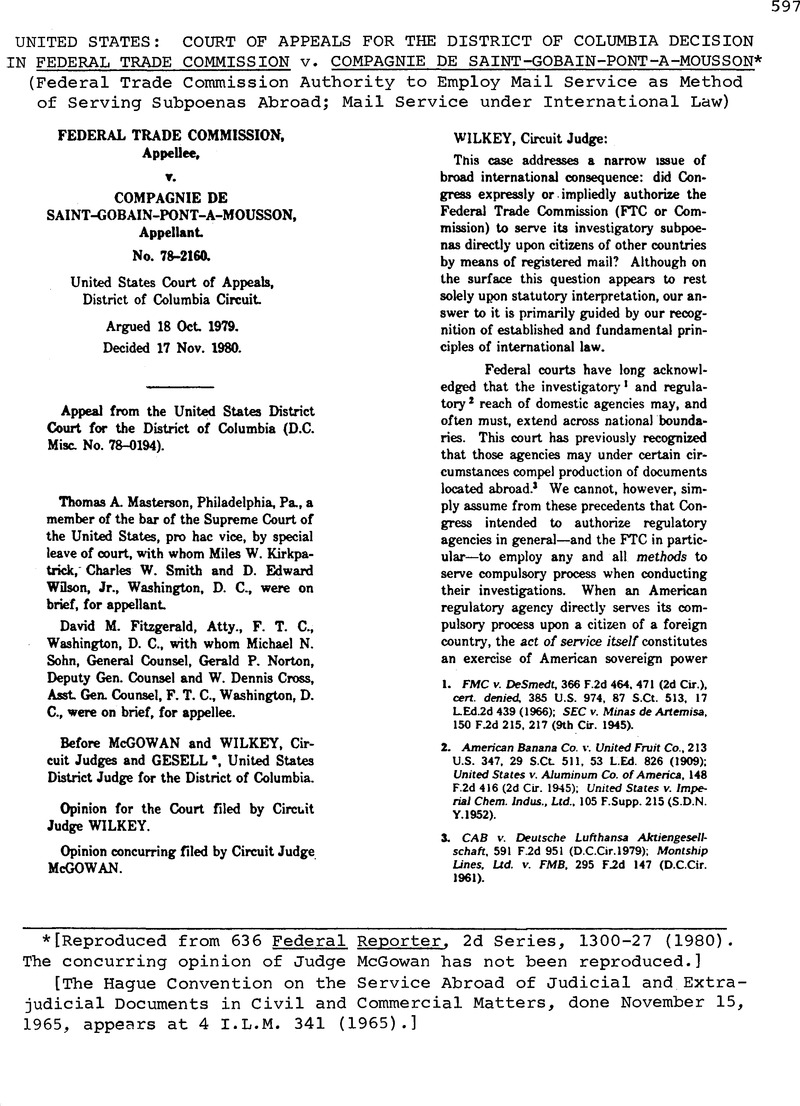

United States: Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Decision in Federal Trade Commission v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1981

Footnotes

[Reproduced from 636 Federal Reporter. 2d Series, 1300-27 (1980). The concurring opinion of Judge McGowan has not been reproduced.]

[The Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil and Commercial Matters, done November 15, 1965, appears at 4 I.L.M. 341 (1965).]

References

1. FMC v. DeSmedt, 366 F.2d 464, 471 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 385 U.S. 974, 87 S.Ct. 513, 17 L.Ed.2d 439 (1966); SEC v. Minas de Artemisa, 150 F.2d 215, 217 (9th Cir. 1945).

2. American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., 213 U.S. 347, 29 S.Ct 511, 53 L.Ed. 826 (1909); United Stales v. Aluminum Co. of America, 148 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945); United States v. Imperial Chem. Indus., Ltd., 105 F.Supp. 215 (S.D.N. Y.1952).

3. CAB v. Deutsche Lufthansa Aktiengesellschaft, 591 F.2d 951 (D.C.Cir.1979); Montship Lines. Ltd. v. FMB, 295 F.2d 147 (D.C.Cir. 1961).

4. 15 U.S.C. § 45 (1976).

5. In particular, the FTC has sought

[t]o determine whether Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corporation, Certainteed Corporation [SGPM’s American subsidiary], Johns-Manville Corporation, Compagnie de Saint-Gobain-Pont-a-Mousson, or others engaged directly or indirectly in the manufacture, distribution or sale of insulation are engaging or have engaged in acts or practices which may have restricted competition in the manufacture, distribution or sale of insulation ... including but not limited to acts or practices relating to licensing of patents applicable to the manufacture of insulation or textile fiberglass, the exchange of technology or know-how applicable to the manufacture of insulation and textile fiberglass, the availability of technology and know-how to potential entrants into the manufacture of insulation, the availability and price of raw materials used to manufacture insulation, the expansion and utilization of insulation manufacturing capacity, and the distribution, allocation and pricing of insulation products.

Resolution Directing Use of Compulsory Process in Nonpublic Investigation, attached as Exhibit 1, Petition for an Order Requiring Respondent to Produce Documentary Evidence in a Federal Trade Commission Investigation, reprinted in Joint Appendix (J.A.) at 36.

6. The subpoenas were issued pursuant to an FTC resolution directing the Commission to use “all compulsory processes available to it” to carry out the investigation. See Resolution Directing Use of Compulsory Process in Nonpublic Investigation, attached as Exhibit 1, Petition for an Order Requiring Respondent to Produce Documentary Evidence in a Federal Trade Commission Investigation, reprinted in J.A. at 36. Each subpoena contained the following language:

You are hereby required to appear before John R. Hoagland, an Attorney and Examiner of the Federal Trade Commission ... to testify in the Matter of Owens-Coming Fiberglas Corporation, et al.

. . . . .

and you are hereby required to bring with you and produce at said time and place the following books, papers, and documents....

Fail not at your peril.

Exhibit 4, Petition for an Order Requiring Respondent to Produce Documentary Evidence in a Federal Trade Commission Investigation, reprinted in J.A. at 126 (emphasis added).

The letter which accompanied each subpoena further stated:

You will take notice that the delivery of this subpoena to you by hand delivery is legal service and subjects you to the penalty imposed by law for failure to appear. For your information, duplicate subpoenas are being served upon you by other means and at other addresses.

Letter from Carol M. Thomas, Secretary, to Compagnie de Saint-Gobain-Pont-a-Mousson, 26 September 1977. attached as Exhibit A. Supplemental Memorandum of Appellant (emphasis added).

7. Petition for an Order Requiring Respondent to Produce Documentary Evidence in a Federal Trade Commission Investigation, reprinted in J.A. at 3.

8. Section 9 of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C § 49 (1976), empowers the Commission:

to require by subpoena the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of all such documentary evidence relating to any matter under investigation....

Such attendance of witnesses, and the production of such documentary evidence, may be required from any place in the United States, at any designated piece of hearing. and in case of disobedience to a subpoena the Commission may invoke the aid of any court of the United States in requiring the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of documentary evidence. (emphasis added).

9. FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, Misc. No. 78-0194, Order to Show Cause (D.D.C. 9 June 1978), reprinted in J.A. at 242.

10. At that time, however, SGPM did not contest the district court’s jurisdiction, for the district court’s order to show cause was served on SGPM’s agent in New York pursuant to Fed.R. Civ.P. 4(i). FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, Misc. No. 78-0194. Order Enforcing Subpoena as modified (D.D.C. 29 Sept 1978). reprinted in J.A. at 421-22.

11. Id.

12. FTC v. Compagnie De Samt-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, Misc. No. 78-0194, Order Denying Respondent’s Motion for Stay Pending Appeal (D.D.C. 30 Oct. 1978). reprinted in J.A. at 450.

13. FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson. No. 78-2160 (D.C.Cir. 26 Nov. 1979) (per curiam).

14. Id., mem. op. at 2 n.2.

15. Id. at 2.

16. Id.

17. Id.

18. The relevant text of the French note read as follows:

The Embassy of France informs the Department of State that the transmittal) by the FTC of a subpoena directly by mail to a French company (in this case Saint-Gobain Pont-à-Mousson) is inconsistent with the general principles of international law and constitutes a failure to recognize French soverignty [sic]. Moreover, the French Government has expressed formal reservations regarding the application in France of the principle of pre-trial discovery of documents characteristic of common law countries.

Furthermore, the response to certain of the requests from the FTC could subject the directors of Saint-Gobain Pont-i-Mousson to civil and criminal liability and therefore ex» pose them to judicial proceedings in France.

Consequently, the Embassy of France would be grateful if the Department of State would make this position known to the various American authorities concerned by informing them that the French Government wishes such steps both in this matter and in any others which may subsequently arise, to be taken solely through diplomatic channels.

Note to the U.S. State Department from the? French Embassy Regarding the FTC Investigation of SGPM, 10 January 1980, (translated by Department of State Division of Language Services) attached as Exhibit B, Supplemental Memorandum of Appellant.

As of this writing, the State Department have offered no response to the French government: note. See note 139 infra.

19. FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson. 493 F.Supp. 286. 290 (D.D.C.1980).

20. Id. [slip opinion] at 14 [unpublished order].

21. See SGPM Brief on Remand at 3-6; SGPM Reply Brief on Remand at 3-4; FTC Memorandum on Remand at 12 n.7. See also FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, 493 F.Supp. 286, 290-291, 293, 294 (D.D.C. 1980). But see note 140 and accompanying text infra.

22. Complaints, orders, and other processes of the Commission under this section may be served ... either (a) by delivering a copy thereof to the person to be served, or to a member of the partnership to be served, or the president, secretary, or other executive officer or a director of the corporation to be served; or ... (c) by mailing ä copy thereof by registered mail or by certified mail ad dressed to such person, partnership, or corporation at Ms or its residence or principal office or place of business. The verified return by the person so serving said complaint, order, or other process setting forth the manner of said service shall be proof of the same, and the return post office receipt for said complaint, order, or other process mailed by registered mail or by certified mail as aforesaid shall be proof of the service of the same. 15 U.S.C. § 45(0 (1976) (emphasis added).

23. See Resolution Directing Use of Compulsory Process in Nonpublic Investigation, reprinted in J.A. at 36 (citing FTC’s statutory authority to issue investigatory subpoenas).

24. See Brief for Appellee at 17; Supplemental Brief of Appellee at 6. See also FTC v. Rubin, 145 F.Supp. 171, 175-76 (S.D.N.Y.1956). rev’d on other grounds, 245 F.2d 60 (2d Cir. 1957) (section 5(f) does not apply to subpoenas).

25. 15 U.S.C. § 46(g) 1976) provides:

The Commission shall also have power—

. . . . .

(g) From time to time to ... make rules and regulations for the purpose of carrying out the provisions of sections 41 to 46 and 47 to 48 of this title.

26. In Hunt Foods & Indus., inc. v. FTC, 286 F.2d 803 (9th Cir. 1960), cert. denied. 365 U.S. 877, 81 S.Ct. 1027, 6 L.Ed.2d 190 (1961). the Ninth Circuit noted:

In our opinion [section 6(g)] is broad enough to authorize the [Federal Trade] Commission to provide by rule for the manner of service of process with respect to those activities and duties concerning which there is no statute expressly applicable.

Id. at 810.

27. At the time the challenged subpoena was served, section 4.4(a)(1) of the FTC’s Rules of Practice and Procedure provided:

Service of subpoenas ... may be effected as follows:

(1) By registered or certified mail—A copy of the document shall be addressed to the person, partnership, corporation or unincorporated association to be served at his, her or its residence or principal office or place of business, registered or certified, and mailed...

16 C.F.R. § 4.4(a) (1978)

Subsequent to the service of the instant subpoena and the district court’s decision, the Commission amended rule 4.4 to provide:

§ 4.4 Service

(a) By the Commission. (1) Service of complaints, initial decisions, final orders, and other processes of the Commission under 15 U.S.C. 45 may be effected as follows:

(i) By registered or certified mail.—A copy of the document shall be addressed to the person, partnership, corporation or unincorporated association to be served at his, her or its residence or principal office or place of business, registered or certified, and mailed; or

(ii) By delivery to an individual.—A copy thereof may be delivered to the person to be served, or to a member of the partnership to be served, or to the president, secretary, or other executive officer or a director of the corporation or unincorporated association to be served; or

(iii) By delivery to an address.—A copy thereof may be left at the principal office or place of business of the person, partnership, corporation or unincorporated association, or it may be left at the residence of the person or of a member of the partnership or of an executive officer or director of the corporation, or incorporated {sic] association to be served.

(2) All other orders and notices including subpoenas, orders requiring-access orders to file annual and special reports, and notices of default, may be served by any method reasonably certain to inforoute affected person. partnership, corporation, or unincorporated association including any method specified is paragraph (a)(1) of this section

43 Fed.Reg. 56.903 (1978) codified at 16 C F R. § 4.4(a)). (emphasis added)

28. 15 U.S.C. § 49 (1976) (emphasis added) For full text, see note 8 supra.

29. Section 9 of the FTC Act derives its language from Interstate Commerce Act § 12, 49 U.S.C. § 12(2) (1976), and incorporates phrases identical to provisions conferring subpoena authority on other agencies, including the CAB, 49 U.S.C. § 1484(c) (1976), the FMC,-46 U.S.C. § 826(a) (1976), and the SEC. 15 U.S.C. § 77s(b) (1976).

30. 366 F.2d 464 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 385 U.S. 974. 87 S.Ct. 513. 17 L.Ed.2d 439 (1966).

31. Section 27, Shipping Act of 1916, 46 U.S.C. § 826 (1976).

32. 49 U.S.C. § 12 (1976) As originally enacts ed, 24 Sut. 383 (1887), and as first amended, 25 Sut. 859 (1889). the ICC Act did not contain the phrase “from any place in the United States.” See 366 F.2d at 470-71.

33. Id.

34. Circuit Judge Moore, dissenting in DeSmedt, observed:

When Congress authorized the production of evidence “from any place in the United States.” it is to be presumed that it was aware of the territory embraced within the United States. If Congress had intended to enact legislation authorizing such production “from any place in the world,” it is again to be presumed that it had available sufficiently skilled draftsmen who could have used “world” instead of “United States”—a not altogether too difficult bit of draftsmanship. The real difficulty which seems to have faced the majority ... is to demonstrate that the “plain” meaning of “United States” is “world.” Even in this day, when these terms appear to be becoming congruous, I find the supposition that Congress could not understand the difference, and hence requires judicial legislation to express in real intent, quite incongruous.

Id. at 474.

In the same dissent Judge Moore commented (hat the Senate had “recognized that the expansion of the FMC’s subpoena power under Section 27 in the face of the strongest possible objection from the Sute Department and explicit directives not to produce documents from numerous friendly maritime nations (including the United Kingdom, Italy and Japan) ‘would only muddy the waters and do violence to our foreign policy ... ’” Id. (citations omitted).

35. 591 F.2d 951 (D.C.Cir.1979) (per curiam) (discussing the CAB’s subpoena authority, conferred by 49 U.S.C § 1484(c) 1976)).

36. Id. at 953.

37. An American court has the power to compel a person over whom it has personal jurisdiction to appear, see, e. g., Blackmer v. United States. 284 U.S. 421. 52 S.Ct. 252, 76 L.Ed. 375 (1932). discussed at notes 110-19 infra and accompanying text, or to produce documents outside the court’s jurisdiction. see SEC v. Minas de Artemisa. 150 F.2d 215, 217 (9th Cir. 1945). See also 5A Moore’s Federal Practice 45.01. 45.07 (2d ed. 1976); Smit, International Aspects of Federal CMI Procedure, 61 Colum. L. Rev. 1031, 1052 (1961); W. Fugate, Foreign Commerce and the Antitrust Laws §§ 3.10-.13 (1958); Gill, Problems of Foreign Discovery, in K. Brewster, Antitrust and American Business Abroad 474-88 (1958); Note. Subpoena of Documents Located in Foreign Jurisdiction where Law of Situs Prohibits Removal, 37 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 295 (1962).

38. In DeSmedt, Judge Friendly relied upon an early case holding that section 19b of the Securities Act of 1933, 15 U.S.C. § 77s(b) (1976), was intended broadly to empower the SEC to require attendance of witnesses or production of documents 366 F.2d at 469. In that case, however, the Ninth Circuit accompanied its finding with the proviso “only that service of the subpoena is made within the terrestrial limits of the United States.” SEC v. Minas de Artemisa, 150 F.2d 215, 218 (9th Cir. 1945) (emphasis added). See also Ludlow Corp. v. DeSmedt, 249 F.Supp, 496. 501 (S.D.N.Y.). aff’d sub nom. FMC v. DeSmedt, 366 F.2d 464 (2d Cir.). cert, denied, 385 U.S. 974, 87 S.Ct. 513, 17 L.Ed.2d 439 (1966) (the sole territorial limitation on the subpoena is that “it be served within the United States”).

39. See FTC Memorandum on Remand at 12 & n.7; Supplemental Memorandum of Appellant at 4. But see text accompanying note 140 infra.

40. FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, 493 F.Supp. 286. 290-291 (D.D.C. 1980).

41. Id. at 291.

42. Id. at 292.

43. Id.

44. Id. at 292-293. citing CAB v. Deutsche Lufthansa Aktiengesellschaft, see notes 35-36 supra and accompanying text; FMC v. DeSmedt, see notes 30-34 supra and accompanying text; and SEC v. Minas de Artemisa, see note 38 supra.

45. FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Cobain-Pont-A-Mousson. 493 F.Supp. 286. 293 (D.D.C. 1980).

46. Id.

47. Id. at 294.

48. Id. at 294-295.

49. See Part B.1 infra.

50. See Part B.2.a infra.

51. See Part B.1 intra.

53. Formal FTC adjudicative proceedings are governed by Part 3 of the FTC Rules of Practice. 16 C.F.R. §§ 3.2 et seq. (1978).

54. See 15 U.S.C. § 21 (1976) (enforcement provisions).

55. Unlike ‘litigative” subpoenas issued in adjudicative agency proceedings, see 16 C.F.R. § 3.34 (1978). investigatory subpoenas are issued under Part 2 of the FTC Rules of Practice, id. at §§ 2.1 et seq., governing nonadjudicative procedures.

56. The Federal Trade Commission Act authorizes a fine of $1000 to $5000 or a year’s imprisonment or both, upon conviction by a court of competent jurisdiction, for any person who refuses to attend or produce documentary evidence “in obedience to the subpoena or lawful requirement of the Commission.” 15 U.S.C. S 50 (1976).

57. The Procedures and Rules of Practice for the Federal Trade Commission, as amended to 1 February 1980, provide the following range of penalties for noncompliance with compulsory processes:

§ 2.13 Noncompliance with compulsory processes

(a) In cases of failure to comply with Commission compulsory processes, appropriate action may be initiated by the Commission or the Attorney General, including actions for enforcement, forfeiture, or penalties or criminal actions.

(b) The General Counsel, pursuant to delegation of authority by the Commission, without power of redelegation, is authorized.

(1) To institute, on behalf of the Commission, an enforcement proceeding in connection with the failure or refusal of a person, partnership, or corporation to comply with, or to obey, a subpoena, if the return date or any extension thereof has passed;

(2) To institute enforcement proceedings on behalf of the Commission and to request on behalf of the Commission the institution of civil actions, as appropriate, in conjunction with the Commission’s quarterly financial reporting program, if the return date or any extension thereof has passed;

(3) To approve and have prepared and issued, in the name of the Commission when deemed appropriate by the General Counsel, a notice of default in connection with the failure of a person, partnership, or corporation to timely file a report pursuant to section 6(b) of the Federal Trade Commission Act [section 46(b) of this title), if the return date or any extension thereof has passed;

(4) To institute, on behalf of the Commission, an enforcement proceeding and to request, on behalf of the Commission, the institution, when deemed appropriate by the General Counsel, of a civil action in connection with the failure of a person, partnership, or corporation to timely file a report pursuant to an order under section 6(b) of the Federal Trade Commission Act [section 46(b) of this title], if the return date or any extension thereof has passed; and

(5) To seek civil contempt in cases where a court order enforcing compulsory process has been violated.

16 C.F.R. § 2.13 (1980).

58. Fed RCiv.P. 81(a)(3) states, in part:

These rules apply to proceedings to compel the giving of testimony or production of documents in accordance with a subpoena issued by an office or agency of the United States under any statute of the United States except as otherwise provided by statute or by rules of the district court or by order of the court in the proceedings;.

59. Fed.R.Civ.P. 45(f).

60. See FTC v. Corpagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, 493 F.Supp. 286, 295-296 (D.D.C. 1980).

61. The general attitude of the federal courts is that the provisions of Rule 4 should be liberally construed in the interest of doing substantial justice and that the propriety of service in each case should turn on its own facts within the limits of the flexibility provided by the rule itself. This is consistent with the modem conception of service of process as primarily a notice-giving device.

62. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 4(d) (giving seven options); 4(e) (giving two options); 4(i) (giving five options).

4 C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil § 1083, at 332-33 (1969 & Supp.1977) (emphasis added). See also id § 1063. at 204:

The primary function of Rule 4 is to provide the mechanisms for bringing notice of the commencement of an action to defendant’s attention and to provide a ritual that marks the court’s assertion of jurisdiction over the lawsuit.

(emphasis added).

63. Compare Fed.R.Civ.P. 45(c) with Fed.R. CİV.P. 4(d)(1).

64. See, e. g., Muilane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306, 314, 70 S.Ct. 652, 657, 94 L.Ed. 865 (1950) (due process permits service of process by mail so long as such service provides “notice reasonably calculated ... to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action”).

65. See note 61 supra.

66. Thus, Professor Miller notes that the Swiss, for example, carefully distinguish between “legal documents issued in connection with the proceedings before a foreign tribunal that are of an informational nature, such as papers notifying the recipient of a tax deficiency or of probate matters, [which] may be served privately in Switzerland without the assistance or intervention of the federal or cantonal authorities” and documents relating to any phase of civil litigation that attempt to command the addressee to appear or perform an act, which may not be served privately. See Miller, International Cooperation in Litigation Between the United States and Switzerland: Unilateral Procedural Accommodation in a Test Tube, 49 Minn.L.Rev. 1069. 1075 (1965) (emphasis added) [hereinafter Miller].

67. “[T]he first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that—failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary—it may not exercise its powers in any form in the territory of another State.” Case of The S.S. “Lotus.” [1927] P.C.I.J. Ser. A., No. at 18. 2 M. Hudson. World Court Reports 20. 35 (1935) [hereinafter The S.S. Lotus]. See also 1 L. Oppenheim, International Law § 144b (8th ed. Lauterpacht 1955) (“States must not perform acts of sovereignty within the territory of other States”).

68. See, e. g., Smit, International Aspects of Federal Civil Procedure, 61 Colum. L. Rev. 1031, 1042 n.58 (1961): “since service [of process] by mail requires activity only on the part of a foreign country’s postal authorities, it is one of the forms of service least likely to be prohibited.” See also 4 C. Wright & A. Miller, note 61 supra, § 1134. at 564 (1969 & Supp.1977): “[S]ervice by mail may be less objectionable than some other method of service to the authorities in a foreign country that frowns upon the performance of ‘sovereign’ or ‘judicial’ acts within its borders on behalf of foreign litigation.”

69. We should note here that direct service of American subpoenas abroad does not always violate international law. A nation may give general consent to service of compulsory process upon its nationals by another nation’s government agencies by signing an international convention. See, e. g., Multilateral Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil and Commercial Matters, done 15 November 1965, [1969] 20 U.S.T. 361, T.I.A.S. No. 6638. 658 U.N.T.S. [hereinafter Hague Convention]. The Hague Convention specifically recognizes, however, a signatory’s right to refuse to honor any particular foreign request for service of judicial documents “if it deems that compliance would in fringe its sovereignty or security.” Id. at art. XIII. See also note 136 infra.

Alternatively, a nation may consent to a particular request for service, and specify an appropriate procedural mechanism whereby the serving nation’s compulsory process may be served on its own citizens, thus minimizing the infringement upon its own sovereignty caused by the service itself. One example of specific consent occurred in November 1961, when the Swiss Embassy delivered an aide-memoire to the Department of State protesting the service by mail of judicial documents on Swiss residents by a U.S. government agency. Observing that “the service of judicial documents on persons residing in Switzerland is, under Swiss law, a governmental function to be exercised exclusively by the appropriate Swiss authorities,” and that “service of such documents by mail constitutes an infringement of Switzerland’s sovereign powers, which is incompatible with international law,” the aide-memoire requested that “documents destined for Switzerland should be transmitted by the U.S. Embassy in Berne to the Federal Division of Police.” The Department of State officially apologized to the Swiss Embassy for its inadvertent violation of applicable Swiss law and directed the responsible American agency to “avoid any future transmittals of such documents in a manner inconsistent with Swiss law.” Dept of State, MS file 711.331/11-1661, 28 Nov. 1961, reprinted in Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law, 56 Am.J. Int’l. 793, 794 (1962).

70. See, e. g.. Professor Wigmore’s discussion of “Compelling an unwilling witness residing abroad”:

For states without the United States ... apart from letters rotatory, what method can be used for compelling the testimony of an unwilling witness there residing?

[T]he forum court in the United States can notify the witness, requesting him to appear before the United States consul for deposing, and upon his failure there to appear or to answer can punish him for contempt (by fine or forfeiture), provided the witness is a citizen of the United Sutes and otherwise is subject to a testimonial duty in the forum court, for his civic duty may extend to conduct abroad as well as at home.

But ... the forum court cannot issue a subpoena to a witness commanding him to appear before the consul, for this would be an attempted exercise of state power within the territory of the foreign state—an intrusion impossible in legal theory and in international understanding.

J. Wigmore, Evidence § 2195c, at 101 (McNaughton rev. ed. 1961) (emphasis added).

71. It is precisely to avoid such bypassing by foreign governments that the Swiss authorities, for example, insist on examining the contents of all judicial documents sent into their country.

The need to examine the contents of foreign documents is ... defended as an integral element of Swiss sovereignty and essential to the national policies of neutrality and protection of commercial and industrial secrets. The theory appears to be that if requests for service were not channeled through and scrutinized by appropriate Swiss officials, there would be no effective way to insure the service of the foreign documents was not contrary to Swiss public policy.

Miller, note 66 supra, at 1076-77.

72. FTC v. Campagnie De Saint-Cobain-Pont-A-Mousson, 493 F.Supp. 286, 294-295 (D.D.C 1980).

73. Fed.R-Civ.P. 4(i)(I)(D).

74. Federal Rule 4(i) provides for five alternative methods by which a party may serve process abroad: in the manner prescribed by the foreign country for service there in a domestic action; as directed by the foreign authority responding to a letter rotatory from the federal court: by personal service; by mail; and as directed by order of the federal court. Rule 4(i) was originally proposed by the Commission and Advisory Committee on International Rules of Judicial Procedure, an official organization having State Department representation, and the text adopted grew out of the cooperation between that agency and the Columbia Project on International Procedure.

The intention of these provisions [was] to provide American attorneys with an extremely flexible framework to permit accommodation to the widely divergent procedures for service of process employed by the various nations of the world. This accommodation is necessary in order to avoid violating the sovereignty of other countries by committing acts within their borders that they may consider to be “official” and to maximize the likelihood that the judgment rendered in the action in this country will be recognized and enforced abroad.

J. Cound. et al. Civil Procedure: Cases and Materials 173 (2d ed. 1974) (emphasis added). See also Miller, supra note 66, at 1075-86.

The Reporter to the Advisory Committee on the Civil Rules at the time rule 4(i) was adopted bas further verified this concern for the territorial sovereignty of foreign countries which led to adoption of the rule. See Kaplan, Amendments of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 1961-1963(1), 77 Harv.L.Rev. 601, 635-36 (1964). See also Smit, International Aspects of Federal Civil Procedure, 61 Colum.L.Rev. 1031, 1047 (1961).

75. See note 74 supra.

76. Cf. Ings v. Ferguson. 282 F.2d 149, 152 (2d Or. 1960) (when foreign procedure for subpoena service exists in a foreign country, the parties should use that procedure rather than running the risk of violating foreign law).

77. See note 18 supra.

78. Restatement (Second) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States §§6-7 (1965) [hereinafter Restatement (Second)]. For a discussion of a third type of jurisdiction, adjudicative jurisdiction, see notes 97-105 and accompanying text infra.

79. See id. at § 6, comment a.

80. Id.

81. Id at §§ 6-7.

82. The Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 116. 136, 3 L.Ed. 287 (1812) (Marshall, C.J.) (“The jurisdiction of the nation, within its own territory, is necessarily exclusive and absolute”).

83. The Appollon, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 362, 370. 6 L.Ed. 111, 112 (1824) (Story, J.) (emphasis added).

84. Restatement (Second) § 17.

85. Id. at § 18. This is the so-called “effects doctrine.” See, e. g., United States v. Aluminum Co. of America, 148 F.2d 416. 444 (2d Cir. 1945) (agreements made abroad between foreigners may violate Sherman Antitrust Act if “intended to affect imports and did affect them”). See also The S.S. Lotus, note 67 supra (criminal offenses committed by perpetrators in another state’s territory may be regarded as committed in the national territory if the effects of the offense are felt in the national territory).

86. Restatement (Second) S 30.

87. See text accompanying note 80 supra.

88. Restatement (Second) at § 7(1). See generally Mann. Prerogative Rights of Foreign States and the Conflict of Laws, 40 Transactions of the Grotius Soc’y 25. 46 (1954).

89. Restatement (Second) at § 20. For exceptions to this rule, see id. §§ 24-25 (jurisdiction conferred by agreement); § 32 (national forces, vessels, and aircraft); § 44(b) (consent by the territorial state).

The problem of enforcement jurisdiction arises when a State acts in foreign territory itself or at least takes measures which, though initiated in its own territory, are directed towards consummation, and require compliance, in the foreign State...

It is in line with the difference in the nature of the problems that entirely different legal principles govern legislative and enforcement jurisdiction respectively. A State which actually attempts to give effect to its legislation in the territory of another State conies into conflict with the latter’s sovereignty. The problems of enforcement jurisdiction, therefore, fail to be considered exclusively from the point of view of the international rights of that State in which the enforcement takes place or is intended to take place.

Mann, The Doctrine of Jurisdiction in International Law. 1 Rec. Des Cours 1, 128 (1964) (emphasis added).

90. M. Restatement (Second) § 7. illustration 1 (emphasis added).

91. Restatement (Second) §§ 8, 3(1).

92. Restatement (Second) § 8, illustration 4 (emphasis added).

93. Onkelinx, Conflict of International Jurisdiction: Ordering the Production of Documents in Violation of the Law of the Situs. 64 Nw.U.L. Rev. 487. 498-99 (1969) (emphasis added) [hereinafter Onkelinx].

This reasoning can perhaps be better understood within the context of out federal system. If a state regulatory agency analagous to the FTC—for example, the New York State Consumer Protection Agency—wanted to compel the appearance, testimony, and production of documents by a California corporation at one of its proceedings, it could issue compulsory process to assist its investigation. Clearly, the New York state legislature would have prescriptive jurisdiction to authorize its Consumer Protection Agency to investigate those activities of out-of-state companies which affect New York commerce. Furthermore, the legislature would have prescriptive jurisdiction to specify the penalties to be imposed upon such companies for any violations of New York unfair trade practice laws.

Yet the existence of New York’s prescriptive jurisdiction over the out-of-state conduct harmful to New York commerce would in no way confer upon the New York courts jurisdiction to enforce, in California, particular subpoenas served upon particular West Coast companies, until some showing could be made that their . activities had harmful effects in New York.

94. Report of the Fifty-First Conference, International Law Association 403, 407 (Tokyo 1964) (emphasis added).

95. See notes 30-34 supra and accompanying text.

96. Report of The Fifty-Second Conference, International Law Association 109, 112 (Helsinki 1966) (emphasis added).

97. Jurisdiction to adjudicate, or “judicial jurisdiction”. refers to a state’s authority to subject persons or things to the process of its courts or administrative tribunals, usually for the purpose of rendering a judgment. Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws 2d §§ 24-26 (1971).

While never renowned as a legal scholar, President andrew Jackson epigrammatically caught the distinction between jurisdiction to enforce and jurisdiction to adjudicate when be said: “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” H. Hockett, Political and Social Growth of the United States (1492-1852) at 502 (1937); M. James, The use of andrew Jackson: Portrait of a President 603 (1937). This remark was made in regard to Chief Justice Marshall’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia. 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515. 8 L.Ed. 483 (1832).

98. Louisville & Nashville R. R. v. Motttey, 211 U.S. 149, 29 S.Ct. 42. 53 L.Ed. 126 (1908); Pennoyer v. Neff. 95 U.S. 714, 24 L.Ed. 565 (1877).

99. Hodgson & Thompson v. Bowerbank, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 303. 3 L.Ed. 108 (1809).

100. Pennoyer v. Nett, 95 U.S. 714, 24 L.Ed. 565 (1877).

101. Traditionally, the defendant’s presence within the territorial jurisdiction of a particular court and service upon that defendant within that territory were considered necessary and sufficient to satisfy due process. Id.

102. Shaffer v. Heitner, 433 U.S. 186. 97 S.Ct. 2569, 53 L.Ed.2d 683 (1977); International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310. 66 S.Ct. 154. 90 L.Ed. 95 (1945).

103. Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306. 70 S.Ct. 652. 94 L.Ed. 865 (1950); Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67, 92 S.Ct. 1983. 32 L.Ed.2d 556 (1972).

104. Although questions of service of process, jurisdiction, and venue often are closely intertwined, service of process is merely the means by which the court, having a sufficient basis for jurisdiction and venue, asserts them over the party and affords him due notice of the commencement of the action.

105. C. Wright 4 A. Miller, 1083, at 335 note 61 supra (emphasis added).

105. Cf. National Equip. Rental. Ltd. v. Szukhent, 375 U.S. 311. 84 S.Ct. 411, 11 L.Ed.2d 354 (1964) (discussing technique of service of process).

106. See notes 41-48 supra and accompanying text.

107. 284 U.S. 421, 52 S.Ct. 252, 76 L.Ed. 375 (1932).

108. FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Gobain-Pont-A-Mousson, 493 F.Supp. 286. 293 (D.D.C. 1980).

109. Id. at n.4.

110. 28 U.S.C. § 711-18 (1926) (current version at 28 U.S.C. §§ 1783-84 (1976)). For the full text of that Act, see Blackmer v. United States, 284 U.S. 421. 433-35 n.1. 52 S.Ct. 252, 253 n.l, 76 L.Ed.2d 375 (1932). The Walsh Act was amended in 1948, see Reviser’s Note, 28 U.S. C.A. § 1783 (1966), and again in 1964, Pub.L. No. 88-619. §§ 10-11. 78 Sut. 997-98. 28 U.S.C. §§ 1783-84 (Supp.1964). As amended, the Act authorizes an American court to issue a subpoena to

a national or resident of the United States who is in a foreign country ... if the court finds that particular testimony or the production of the document or other thing by him is necessary in the interest of justice, and, in other than a criminal action or proceeding, if the court finds, in addition, that it is not possible to obtain his testimony in admissible form without his personal appearance or to obtain the production of the document or other thing in any other manner.

28 U.S.C. § 1783 (1976).

111. See Blackmer v. United States, 284 U.S. 421, 434-35. 52 S.Ct. 252, 253-54. 76 L.Ed. 375 (1932).

112. Id. at 436. 52 S.Ct at 254.

113. Id. at 437-38. 52 S.Ct at 254-55.

114. “The jurisdiction of the United States over its absent citizen, so far as the binding effect of its legislation is concerned, is a jurisdiction in personam, as he is personally bound to take notice of the laws that are applicable to him and to obey them.” Id. at 438. 52 S.Ct at 255. The Blackmer Court specified, however, that [t]he instant case does not present the questions which arise in cases where obligations inherent in [national] allegiance are not involved.” Id. at 438 n.5. 52 S.Ct at 255 n.5 (emphasis added).

115. Id. at 436. 52 S.Ct at 254.

116. 28 U.S.C. § 1783. as amended to codify the Blackmer holding, expressly limited the authority of the federal courts to issue subpoenas to “national[s] or residents] of the United State« ... in a foreign country.” See note 110 supra. Because the Walsh Act had been interpreted in Blackmer as an exercise of American power over its own citizens, the Act has never been read as permitting issuance of a subpoena to an alien residing outside the United States. See, e. g., Gillars v. United States, 182 F.2d 962 (D.C. Cir. 1950) (“Aliens who are inhabitants of a foreign country cannot be compelled to respond to a subpoena. They owe no allegiance to the United States,” citing United States v. Best, 76 F.Supp. 138. 139 (D.Mass.1948)); Gallagher, Subpoena Service on Citizens Residing Abroad, 12 Int’l Law. 563 (1978) (discussing Blackmer).

Although the Walsh Act was again amended in 1964 to provide for subpoena service “in accordance with the provisions of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure relating to service of process on a person in a foreign country.” including registered mail, the express purpose of the amendment was to “substantially enhance the probability that the service can be made without offending the sensibilities of foreign sovereigns.” Smit, International Litigation Under the United States Code, 65 Colum.L. Rev. 1015. 1038 (1965) (emphasis added). Compare notes 73-75 supra (discussing policy underlying rule 4(i)). See also Smit. International Aspects of Federal Civil Procedure, 61 Colum.L.Rev. 1031. 1047 (1961).

117. The Blackmer Court’s resolution of that issue did not, therefore, dispose of the question here. The fact that a state has prescriptive Jurisdiction over a certain type of conduct does not necessarily validate every method by which that state may choose to serve compulsory process for the purposes of investigating that conduct. This is clear even within the boundaries of the United States, if the hypothetical New York regulatory agency described in note 93 supra wanted to compel the appearance of or production of documents by a California corporation in an investigation of that corporation’s anticompetitive activities, it would still have to take heed of possible infringements upon California state sovereignty resulting from it use of a particular mode of serving its compulsory process. New York’s prescriptive jurisdiction over the anticompetitive conduct in question would not validate service of compulsory process by registered mail, for example, given the requirement of personal service of subpoenas found in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. See notes 63-64 supra and accompanying text.

118. See text accompanying note 124 infra. But see note 140 infra.

119. We assume that just as a court may not validly exert its adjudicative authority over a defendant lacking “minimum contacts” with the forum, see notes 100-02 supra and accompanying text, the FTC is subject to some limitations on its personal jurisdiction—set by the due process clause of the Constitution—which bar it from exercising its investigative authority over a foreigner lacking any contacts with the United States.

For reasons that remain unclear, however, respondent here has repeatedly conceded the FTC’s power to issue an investigatory subpoena directed at obtaining the particular documents sought in this investigation. See Transcript of Oral Argument FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Cobain-Pont-A-Mousson at 14, 30-31, No. 78-2160 (D.C. Cir. 26 Nov. 1979).

Thus, in our memorandum opinion remanding the record to the district court, we noted that:

Appellant did not urge, either upon this court or the District Court, that documents located abroad were beyond the reach of the Commission’s subpoena authority. Indeed, its actions in the District Court, and its representations on appeal, assume the contrary. It rather has insisted only that service of any subpoena directed at documents abroad could lawfully be made only in the United States.

120. See notes 41-46 supra and accompanying text.

121. See Parts B.1 & B.2 supra.

122. 15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(6) (1976).

123. 15 U.S.C. § 44 (1976).

124. 15 U.S.C. § 46(h) (1976).

125. See, e. g., Endicott Johnson Corp. v. Perkins. 317 U.S. 501. 63 S.Ct. 339. 87 L.Ed. 424 (1943); Oklahoma Press Publishing Co. v. Walling, 327 U.S. 186. 66 S.Ct. 494, 90 L.Ed. 614 (1946).

126. See, e. g., FTC v. Browning, 435 F.2d 96. 99-100 (D.C. Cir. 1970); Hunt Foods & Indus. Inc. v. FTC, 286 F.2d 803 (9th Cir. 1960). cert. denied, 365 U.S. 877. 81 S.Ct. 1027, 6 L.Ed.2d 190 (1961).

127. For the distinction between subject matter jurisdiction and technique of service, see notes 97-105 and accompanying text supra.

128. 336 U.S. 281, 285. 69 S.Ct. 575. 577, 93 L.Ed. 680 (1949). See also Restatement (Second) § 38.

129. See FTC v. Compagnie De Saint-Cobain-Pont-A-Mousson, No. 78-2160. mem. op. at 2 (D.C. Cir. 26 Nov. 1979).

130. See Murray v. The Schooner Charming Betsy, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 64. 118. 2 L.Ed. 61,116 (1804) (“[A]n act of congress ought never to be construed to violate the law of nations, if any other possible construction remains....”)

This principle has been adopted by this Circuit. See Pacific Seafarers, Inc. v. Pacific Far East Line. Inc., 404 F.2d 804, 814 (D.C. Cir.). cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1093. 89 S.Ct 872, 21 L.Ed.2d 784 (1968):

[I]t may fairly be inferred, in the absence of clear showing to the contrary, that Congress did not intend an application that would violate principles of international law.

131. See Restatement (Second) § 38, Reporters’ note 1.

132. See Part B.1 supra.

133. See Part B.2.a supra.

134. We cannot ignore the fact that the scope of administrative agency investigatory and regulatory jurisdiction has expanded enormously since the FTC Act was enacted in 1914. Yet it Kerns reasonable, when construing a statute potentially in conflict with international law, to assume that legislation enacted when U.S. government regulation was less pervasive is less likely than more recent legislation to reflect a congressional intent to have effect outside the nation’s borders.

135. Fed.R.Civ.P. 45(c) provides:

A subpoena may be served by the marshal, by his deputy, or by any other person who is not a party and is not less than 18 years of age. Service of a subpoena upon a person named therein shall be made by delivering a copy thereof to such person and by tendering to him the fees for one day’s attendance and the mileage allowed by law. When the subpoena is issued on behalf of the United States or an officer or agency thereof, fees and mileage need not be tendered.

136. The Hague Convention, note 69 supra, establishes standard procedures for service of judicial and extrajudicial documents in the territory of one contracting nation in aid of private commercial or civil litigation taking place in another contracting nation. For a discussion of the Hague Convention, see generally Amram. Report on the Tenth Session of the Hague Conference on Private International Law. 59 Am. J. Int’l L. 87, 90-91 (1965); Nadelmann. The United States Joins the Hague Conference on Private International Law, A History with Comments, 30 Law & Contemp. Prob. 291, 309-10 (1965) France is a signatory of the Convention.

In addition, both the United States and France have participated in a more recent effort to facilitate the process of obtaining evidence abroad—The Multilateral Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters, done 18 March 1970. [1972] 23 U.S.T. 2555, T.I-A.S. No. 7444, of which the Convention on Serving Judicial Documents is revised chapter 1.

Even if the Hague Convention does not apply to service by a United States government agency, see First Affidavit of Professor Covey T. Oliver, attached to SGPM Brief on Remand, at 5-6; Second Affidavit of Professor Pierre Mayer, attached to SGPM Brief on Remand, at 9, service by some other channel mutually acceptable to both governments is not precluded. See, e. g., Tamari v. Bache & Co. (Lebanon), 431 F.Supp. 1226 (N.D.Ill.) aff’d, 565 F.2d 1194 (7th Cir. 1977). cert, denied, 435 U.S. 905. 98 S.Ct. 1450. 55 L.Ed.2d 495 (1978).

137. See Fed.R.Civ P. 45(c), cited in full at note 135 supra.

138. See, e. g., In re Equitable Plan Co., 185 F.Supp. 57 (S.D.N.Y.), mod. sub nom. Ings v. Ferguson, 282 F.2d 149 (2d Cir. 1960) (permitting such a mode of service).

139. See note 69 supra.

Such a reading of congressional intent would have seemed flatly inconsistent with American diplomatic efforts to create regularized intergovernmental channels of international judicial assistance which enable government authorities to seek evidence abroad with a minimum of infringement on national sovereignty. See generally H. Smit & A. Miller. International Cooperation in Civil Litigation—A Report on the Practices and Procedures Prevailing in the United States (1961); Jones, , International Judicial Assistance: Procedural Chaos and a Program for Reform, 62 Yale I.J. 515 (1953)Google Scholar; Note, , Taking Evidence Outside of the United States, 55 B.U.L. Rev. 368 (1975).Google Scholar

It is worth noting that although the French government sent a note of protest to the United States State Department on 10 January 1980 with regard to the FTC’s attempt to serve its compulsory process by mail, see note 18 supra, as of this writing, the Department has yet to respond to the French protest. It seems likely that the State Department has found H difficult to defend the FTC’s willingness to circumvent established international channels for delivering its compulsory process.

140. See the new section 20(c)(6)(B) of The FTC Act, governing civil investigative demands, added by § 13 of The Federal Trade Commission Improvements Act of 1980. Pub.L.No. 96-252, 94 Stat. 381 (enacted 28 May, 1980) (emphasis added). We have become aware of the passage of these amendments without the assistance of counsel for either the FTC or SGPM. These amendments replace the FTC’s subpoena authority in certain Commission consumer protection investigation cases with C.I.D. authority virtually identical to that conferred upon the Justice Department by the Antitrust Civil Process Act, 15 U.S.C. 1312(d)(2) (1976). Ironically, these amendments to the FTC Act were viewed by the Senate as limiting rather than expanding the FTC’s authority to conduct its investigations. See S.Rep.No. 96-500. 96th Cong., 1st Sess. at 23-26 (1979). Since these amendments obviously apply only prospectively, they do not affect our analysis of the invalidity of the mode of service employed in this case.- If anything, the passage of these amendments buttresses the argument already made, for it indicates that when Congress intends to authorize extraterritorial service of investigative subpoenas, it will express that intent explicitly.

141. See note 119 supra.

142. See Part B.1 supra.

143. See, e. g., the reaction of the British House of Lords to American government support of Westinghouse’s efforts to take the testimony of British witnesses to an alleged uranium price-fixing conspiracy. Rio Tinto Zinc Corp. v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., [1978] 2 W.L.R. 81 (House of Lords). For a discussion of the controversy stimulated by the ongoing Westing-house litigation. In re Westinghouse Elec. Corp. Uranium Contracts Litigation (Rio Algom), 563 R2d 992 (10th Cir. 1977), see generally Mehrige, . The Westinghouse Uranium Case: Problems Encountered in Seeking Foreign Discovery and Evidence, 13 Int’l Law. 19 (1979)Google Scholar.

One commentator, remarking upon the plethora of governmental protests which followed a U. S. district court’s order to produce documents almost three decades ago. In re Investigation of World Arrangements, 13 F.R.D. 280 (D.D.C.1952). stated:

From the many protests against the attempts of United States courts to secure documents which are located abroad, one thing seems quite clear every foreign government considers this attempt as an infringement upon its sovereignty and as beyond the jurisdiction of the United States according to international law.

Onkelinx, supra note 93, at 499.

144. See, e. g., Onkelinx, supra note 93; Note, Foreign Non-disclosure Laws and Domestic Discovery Orders in Antitrust Litigation, 88 Yale L.J. 612 (1979) [hereinafter Yale Note]; Note, Discovery of Documents Located Abroad in U. S. Anti-trust Litigation: Recent Developments in the Law Concerning the Foreign Illegality Excuse for Non-Production. 14 Va. J. Intl L. 747 (1974) [hereinafter Virginia Note]; Note. Ordering Production of Documents from Abroad in Violation of Foreign Law, 31 U.Chi.L.Rev. 791 (1964); Note, Limitations on the Federal Judicial Power to Compel Acts Violating Foreign Law, 63 Colum.L.Rev. 1441. 1458-65 (1963); Note, Subpoena of Documents Located in Foreign Jurisdiction where Law of Situs Prohibits Removal, 37 N.Y.U.L.Rev. 295 (1962).

145. At the close of 1979, six foreign states and two Canadian provinces had enacted “blocking statutes,” designed to protect their citizens against official inquiries by authorities of other states. Yale Note at 613 nn.5-6. Foreign non disclosure statutes have been of two types—the first, providing that a government official may, in his discretion, prohibit the production of a class of documents, see, e. g.. Foreign Proceedings (Prohibition of Certain Evidence Act), 1976, Austl. Acts No. 121, § 5. and the second, prohibiting production of any documents requested by a foreign tribunal unless those documents are of a type normally sent out of the province in the regular course of business, see, e. g., Business Concerns Records Act, 1964, Que.Rev.Stat. c. 278 (1964).

The British legislature has recently enacted legislation of the first type, see Protection of Trading Interesu Act, 1980, c. 11 § 2, 20 Mar. 1980, while the French government has promulgated in the last few months legislation of the second type, see notes 146-47 infra.

146. French Law No. 80-538. titled “Law concerning the communication of documents or information of an economic, commercial, industrial, financial or technical nature to aliens, whether natural or artificial persons,” provides in Article 1:

Without prejudice to international treaties or agreements, a natural person of French nationality or customarily residing on French territory, or director, representative, agent or official of an artificial person with headquarters or an establishment on French territory, shall not communicate in writing, orally, or in any other form, regardless of place, to the public authorities of another country documents or information of an economic, commercial, industrial, financial or technical nature where such communication is liable to threaten France’s sovereignty, security or basic economic interests or the public order, as defined by the administering authority when necessary.

Journal Officiel de la Republique Francaise (17 July 1980) (translation provided by SGPM; uncontroverted by FTC) (emphasis added). Article 3 of that law further specifies:

Without prejudice to more serious penalties provided by law, any violations of articles 1 and 1a of this law shall be punishable by two to six months’ imprisonment and a fine of from 10,000 to 120,000 francs [$2,500 to $30,000] or either one of these two penalties alone.

id.

147. Article la of the French statute provides:

Without prejudice to international treaties or agreements and to current laws and regulations, a person shall not ask for, seek or communicate in writing, orally, or in any other form, documents or information of an economic, commercial, industrial, financial or technical nature that may constitute proof with a view to legal or administrative proceedings in another country or in the framework of such proceedings.

Id. (emphasis added).

Thus, not only would the FTC’s act of delivering its subpoena threaten French sovereignty. its request for the documents would itself constitute a prima facie violation of French law subject to enforcement by criminal penalties.

148. The district court would first have to determine whether the French statute was applicable to this subpoena (which issued prior to the passage of the French law) and to those subpoenaed documents which, though under the control of SGPM, may be within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. Furthermore, the district court would have to consider whether SGPM had made good-faith efforts to secure the permission of the French government to produce the documents despite the French statute, and then weigh the respective interests of the United States and France. See generally Restatement (Second) § 39-40. Societe internationale v. Rogers, 357 U.S. 197. 78 S.Ct. 1087. 2 L.Ed.2d 1255 (1958); In re Westinghouse Elec. Corp. Uranium Contracts Litigation (Rio Algom), 563 F.2d 992, 997-99 (10th Cir. 1977). For detailed discussion of how district judges have traditionally made this determination, see generally Onkelinx, supra note 93; Yale Note, supra note 144; Virginia Note, supra note 144.

In view of the interpretation of French law which would be necessary, see notes 146-47 supra, a district court might see fit to defer to the judgment of a foreign court regarding the applicability of the law. See, e. g., lugs v. Ferguson, 282 F.2d 149. 152 (2d Cir. 1960).

148. See, e. g., In re Chase Manhattan Bank, 297 F.2d 611 (2d Cir. 1962) (Panamanian law); First Naf’l City Bank v. IRS, 271 F.2d 616 (2d Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361 U.S. 948, 80 S.Ct 402. 4 L.Ed.2d 381 (1960) (same).

150. Principles of international comity require that domestic courts not take action that may cause the violation of another nation’s laws. See Note, Ordering Production of Documents from Abroad in Violation of Foreign Law, 31 U.Chi.L.Rev. 791. 794-96 (1964).