No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

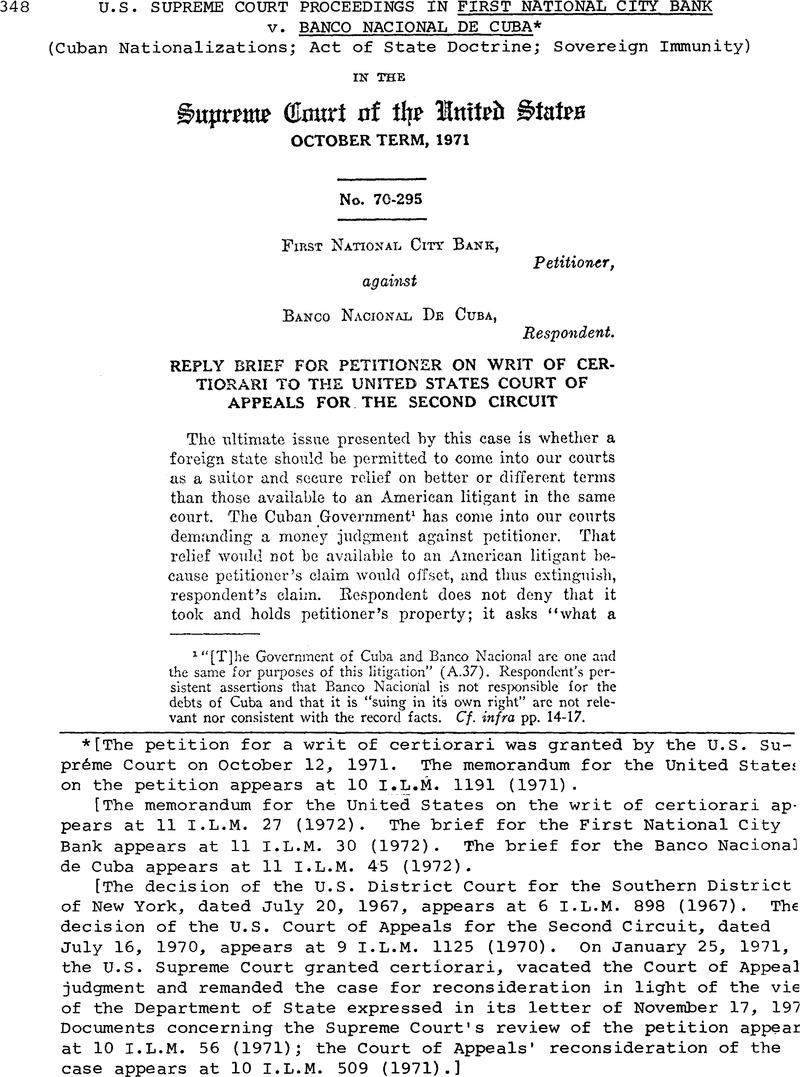

U.S. Supreme Court Proceedings in First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1972

Footnotes

[The petition for a writ of certiorari was granted by the U.S. Supréme Court on October 12, 1971. The memorandum for the United States on the petition appears at 10 I.L.M. 1191 (1971).

[The memorandum for the United States on the writ of certiorari appears at 11 I.L.M. 27 (1972). The brief for the First National City Bank appears at 11 I.L.M. 30 (1972). The brief for the Banco Nacional de Cuba appears at 11 I.L.M. 45 (1972).

[The decision of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, dated July 20, 1967, appears at 6 I.L.M. 898 (1967). The decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, dated July 16, 1970, appears at 9 I.L.M. 1125 (1970). On January 25, 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari, vacated the Court of Appeal judgment and remanded the case for reconsideration in light of the vie of the Department of State expressed in its letter of November 17, 197 Documents concerning the Supreme Court’s review of the petition appear at 10 I.L.M. 56 (1971); the Court of Appeals’ reconsideration of the case appears at 10 I.L.M. 509 (1971).]

References

1 “[T]he Government of Cuba and Banco Nacional are one and the same for purposes of this litigation” (A.37). Respondent’s persistent assertions that Banco Nacional is not responsible for the debts of Cuba and that it is “suing in it’s own right” are not relevant nor consistent with the record facts. Cf. infra pp. 14-17.

2 White House Press Release, January 19, 1972, entitled “Policy Statement: Economic Assistance and Investment Security in Developing Nations.”

3 The New York Times, January 20, 1972, p. 1, col. 1.

4 Pet. Br. pp. 18-21.

5 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (1). The Constitution gives Congress the power to “define . . . Offences against the Law of Nations”, Art. 1, § 8, cl. 10, and to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations”, §8, cl. 3; cf. §8, cl. 18. Congress clearly has power to attach legal consequences to acts occurring abroad which affect United States interests. United States v. Aluminum Company of America, 148 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945) ; Schoenbaum v. Firstbrook, 405 F.2d 200 (2d Cir. 1968), reh. en banc 405 F.2d 215, cert. den. sub nom. Manley v. Schoenbaum, 395 U.S. 906 (1969). “This power is in accord with international law. S.S. Lotus, P.C.I.J. ser. A, No. 10 (1927), 22 Am. J. Int’l L. 8 (1928); Restatement, 2nd, Foreign Relations Law of the United States, § 18 (1965).

6 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (2).

7 (A. 41). The court of appeals believed that the Hickenlooper Amendment, 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (2), did not lift the procedural bar of the act of state doctrine in this case, but it did not disturb or question Judge Bryan’s finding that the first part of that statute, 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (1), is a substantive rule of general application.

8 Respondent’s contention that the Cuban view of international law is that no compensation need be paid for nationalized property is flatly contradicted by Article 24 of the Fundamental Law of Cuba (Pet. Br., p. 6a) and the lip-service given to the principle of compensation in the nationalization statute itself (id., p. 2a). In the light of these Cuban statutes, respondent is less than candid in its assertions that “Petitioner provides no hint as to the basis for the right of compensation on which it relies” (Resp. Br., p. 24) and that “Petitioner has not argued that it is entitled to recovery under Cuban law” (Resp. Br., p. 25, but see Pet. Br., p. 19 and Petition for Writ of Certiorari, pp. 14-15). Respondent’s argument really comes down to this: that by failing to meet the dictates of its own law and by violating the principles it has professed and solemnly proclaimed, Cuba has made those principles disappear.

9 See 307 F.2d, 863, n. 12 for a listing of other authorities on the subject, considered by the Second Circuit but not included in respondent’s list at Resp. Br. p. 41, n. 22, and 307 F.2d, 863, n. 11 for a listing of ten cases predicated upon the proposition that compensation is due for government taking. Our own courts have held the United States itself responsible for damage claims under international law even where United States local law provided no remedy. Royal Holland Lloyd v. United States, 73 C. CI. 722 (1932). See also Wortley, Expropriation in Public International Law, 33-36 (1959) for a list (which Professor Wortley characterizes as “not exhaustive”) of some thirty authorities in various countries, holding the view that compensation is required. That this is the “prevailing view”, is indicated in Baade, Indonesian Nationalization Measures Before Foreign Courts—A Reply, 54 Am. J. Int’l. 801, 808 (1960). It can hardly be said that the authorities are in “sharp conflict” (Resp. Br. p 41).

10 In reference to respondent’s version of the Indonesian Nationalization cases (Resp. Br. p. 44, n. 24), we point out that in the Rome litigation (as in the I.C.J, litigation: Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case (United Kingdom v. Iran), I.C.J. Rep. (1952) 92), the issue was discrimination against Anglo-Iranian, not whether compensation had been paid or offered. (Cf. Judge Carniero’s dissenting opinion in the I.C.J, case, at pp. 151, 159-60, 162 for a cogent statement of the rationale of the compensation rule.) Indeed, in the Venice litigation, Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Ltd. v. S.U.P.O.R. (The Miriella), Italy, Court of Venice (1955) Int’l. L. Rep. 19, 20, 23, the Court noted that Mr. Mossadegh, then head of the Persian Government, had himself offered compensation to Anglo-Iranian, and confirmed his obligation to pay before the International Court of Justice. The High Court of Tokyo, in reviewing the Tokyo District Court decision cited by respondent, indicated that it did not pass on the validity or invalidity of the nationalization law despite the alleged failure to compensate because “we do not think these matters are contrary to the public policy of this country [Japan].” This statement should be contrasted with the public policy of the United States as expressed in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1964 as amended. See, generally, 6 Whiteman, Digest of International Law, 1-54; 8 Whiteman, Digest of International Law, 1053-1057, 1170-1178, 1095, 1096. Justice White lists other examples of judicial examination of foreign acts of state at 376 U.S.. 440, n. 1.

11 Justice White has observed that “American courts have denied recognition or effect to foreign law, otherwise applicable under the conflict of laws rules of the forum, to many foreign laws where these laws are deeply inconsistent with the policy of the forum, notwithstanding that these laws were of obvious political and social importance to the acting country.” 376 U.S., 447 (dissenting opinion).

12 The stipulation provides that “if the defendant [petitioner] is lawfully entitled to the offset claimed by it, the amount thereof is such that plaintiff [respondent] will take nothing in this action” (A.4).

13 National City Bank v. Republic of China, 348 U.S. 356 (1955); A.82-86; Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae, p. 4. See, State of Russia v. Bankers Trust Co., 4 F. Supp. 417 (S.D.N.Y. 1933), aff’d sub nom. United States v. National City Bank, 83 F.2d 236 (2d Cir. 1936), cert. den. 299 U.S. 563.

14 The purpose of the Act is to provide for the determination of the amount and validity of U.S. claims against Cuba, 22 U.S.C. § 1643. There is no Congressional intent to vest Cuban property. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee struck from the Act § 1643j(b), which provided for vesting, because of the objection of the Department of State that “to vest and sell Cuban assets would place the Government of the United States in the position of doing what Castro has done. It could cause other governments to question the sincerity of the United States Government in insisting upon respect for property rights.” Sen. Rep. No. 701, 89th Cong. 1st Sess., p. 3. The Senate Committee also indicated that assets “wholly or substantially” owned by United States residents should not be blocked at all so no property of a United States citizen could be used to pay the claims of another United States citizen against Cuba. Id., p. 5. It has been pointed out that the purpose of this Act is consistent with our reading of the purpose of the Hickenlooper Amendment, and not contrary to it. Note, 42 N.Y.U. J.Int’l L. & Pol. 260 (Summer, 1971).

15 (A. 20) ; cf. Pet. Br. p. 19; note 8, supra.

16 Pp . 2-7, supra.

17 Pet. Br. pp. 18-20.

18 The Sabbatino opinion was directed only to “the validity of a taking of property within its own territory by a foreign sovereign government” [emphasis added], not to the questions of indemnity or compensation due. 376 U.S., 428.

19 (A. 39-45) ; Appendix G to Petition for Writ of Certiorari (70-295) ; see the authorities listed at p. 12, n. 5 of our main brief for an extensive listing of legislative history in support of this proposition.

20 (A. 82-86); Memorandum for United States as Amicus Curiae, p. 2.

21 See Pet. Br. p. 9. Respondent’s reliance upon Pons v. Republic of Cuba, 294 F.2d 925 (D.C. Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U.S. 960 (1962) is misplaced and its statement of that case (Resp. Br. p. 9) is misleading. Pons was a Cuban national and an agent of the Cuban government, stationed in the United States. Cuba filed, in the District Court for the District of Columbia, a claim against Pons for $120,000. Pons responded by claiming that some $63,500 had been paid by him in discharge of a debt of Cuba; he deposited the balance ($56,454.72) in the Court’s registry and asserted a counterclaim of $66,500, being the value of property in Cuba which he alleged the Cuban government had taken from him “without any legal justification and without due process of law”. 294 F.2d 925, at 926. The District Court dismissed that counterclaim and the Court of Appeals affirmed, on the ground that what another country has done in the way of taking over property of its nationals is not a matter for judicial consideration in the United States. 294 F.2d at 926, citing United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, (1937), 332. The District Court left undecided Cuba’s claim for the additional amount ($63,545.28) for which, in effect, Pons had successfully claimed an offset. In these circumstances, Pons provides no support for respondent’s arguments as to the act of state doctrine and respondent’s representation (Resp. Br. p. 14) that “the facts in the Pons case were the same as in the present case save “the party in office has changed” is not correct.

22 [T]he majority, by applying the act of state doctrine after an independent evaluation of the merits of the State Department’s decision, is usurping the same executive prerogative which it is the function of that doctrine to preserve.” A.87. (Hays, J.).

23 See Resp. Br. pp. 8-15. But see Memorandum for United States as Amicus Curiae, pp. 2, 3 ; A.86, 87

24 Resp. Br. pp. 11, 12, 14, 15.

25 Second amended reply, par. 9 (A.30) ; Pet. Br. pp. 5, 3a; Cuban Executive Power Resolution No. 2 (Def. Mot. Exh. 22) (A.42, n. 6).

26 Amended complaint, par. 8 (A. 12).

27 Amended complaint, par. 10 (A. 13).

28 827 F.R.D. 255, 258 (S.D.N.Y. 1961). The cases cited in Point V of respondent’s brief are irrelevant where, as here, the public corporation sues on behalf of the government and the counterclaim is asserted against the government.

29 In English translation, Fondo de Establizacion de la Moneda