When the science fiction writer Frank Herbert approached publishers with his second novel, they were far from enthusiastic. Twenty-three rejected the work in various incarnations.Footnote 1 It was unusually long – 215,000 words – and it was weird. The publisher that finally took it, Chilton, was best known for its auto-repair manuals. Chilton did little to push the book; the first print run in 1965 was 2,200 copies, and there wouldn't be another for three years.Footnote 2 Reviewers didn't take to it, either. It was a “sort of third rate Civil War novel” swaddled in “mystic confusion,” wrote one.Footnote 3

Still, the weighty book won prizes – the Hugo and Nebula awards – and collected readers. “Word is spreading on the West Coast grapevine about an epic science fiction novel titled Dune,” the Boston Globe's youth column reported in 1969.Footnote 4 You could see why. The novel's characters took psychedelic drugs, meditated, communed with nature, practiced mysticism, and staged orgies. As the counterculture grew, Dune's sales swelled. By Herbert's death in 1986, Dune and its sequels – he wrote five – had collectively sold thirty-five million copies.Footnote 5

Dune still sells briskly. Wired magazine recently declared it “one of the most influential sci-fi books ever,” and a BBC Arts panel placed it among the hundred “most inspiring” novels.Footnote 6 Major figures across the political spectrum – environmentalist Stewart Brand, television host Stephen Colbert, mogul Jeff Bezos, white power advocate Richard Spencer – have declared their love for Dune. George Lucas channeled many of its ideas into his Star Wars films, and Dune spawned major films of its own, in 1984 and 2021.Footnote 7 It has also been adapted for television, made into an influential video game, and analyzed endlessly online. There are whole countries whose Wikipedia pages are shorter than Dune's.

Unsurprisingly, Dune has attracted scholarly attention, too, much of it about the novel's ecological themes.Footnote 8 Dune started to appear in serial in 1963, just a year after Rachel Carson's breakthrough Silent Spring. Like Carson (whom Herbert read), Herbert promoted ecological consciousness.Footnote 9 Dedicated “to the dry-land ecologists,” Dune told of a once-verdant planet, Arrakis, that had grown barren yet might, with sensitive intervention, bloom again.Footnote 10 Herbert called Dune “an environmental awareness handbook,” and he spoke at the first Earth Day in 1970.Footnote 11

Ecology is indeed important to Dune, yet it doesn't appear unaccompanied. Herbert tells his environmental parable as a saga of empire. Like much science fiction, Dune highlights war, colonization, and clashing cultures – not entirely a surprise for a genre with roots in the history of imperialism.Footnote 12 Scholars have thus sought to make sense of Dune as a reflection on empire from the heyday of decolonization.Footnote 13

In this article, I argue that empire is not only a textual theme of Dune but a deeply contextual one, too. Before becoming a full-time novelist, Herbert worked as a political aide, which brought him close to the men who ran the United States’ overseas empire.Footnote 14 At the same time, he lived in a region – the Pacific Northwest – where settler colonialism's legacy was vividly on display, which brought him close to Indigenous interlocuters, particularly from the extended Quileute community. To see what's most fully at stake in Dune, this article turns to contexts overlooked in studies of Herbert, including oil extraction on the continental shelf, Mexican agriculture, and the Quileute reservation's environmental history. And it turns to new sources, such as interviews, ethnographies, and Indian rolls. Together, these allow us to tell an ampler story about Dune and empire. They also help explain Herbert's environmentalism.

Reading Dune in the light of Herbert's imperial entanglements is a reminder that, for men like him, empire wasn't an abstraction but a series of material investments around which lives were lived and careers made. Their country was engaged in an ongoing project of settler colonialism, maintained overseas territories, and intervened by various means abroad. These were not auxiliary facts but controlling ones, marking many aspects of twentieth-century US history. The enormously popular Dune is a potent example of empire's insistent presence within the politics and culture of the United States.Footnote 15

Empire was on Herbert's mind from the start. Much like Joseph Conrad, who as a boy was transfixed by the blank spaces on the map of Africa, Herbert had a “lifelong fascination with remote regions of the Earth, from frozen locales to tropics to deserts,” according to his son and biographer, Brian Herbert.Footnote 16 On his eighth birthday, in 1928, Frank announced his intention to be an author. That day, he wrote his first short story, “Adventures in Darkest Africa,” about a hero facing various jungle hazards.Footnote 17

Boyhood fantasies of brave scouts in forbidding locales weren't uncommon then.Footnote 18 But for Herbert, they were more than fantasies; hunting and camping formed a regular part of his young life in Washington State. At some point in the 1930s, while fishing on Fox Island in Puget Sound, Herbert met a Hoh man named “Indian Henry” in his late forties, who “semi-adopted Frank,” Brian Herbert writes. Henry “hinted at something troublesome in his past,” though Frank never learned what. The two became “fast friends,” and for two years Henry taught Frank “the ways of his people,” including how to identify useful plants and find food.Footnote 19

This story, told by Frank Herbert to his son, has the air of a tall tale. The historian Philip Deloria has written of the all-too-familiar trope: “an old Indian person who, for whatever reason, turns, not to other Indians, but to a good-hearted white writer to preserve his or her sacred knowledge.”Footnote 20 An Indian living alone in the woods, waiting to pass on his wisdom to a plucky white boy, seems clichéd enough that it's tempting to file the story alongside “Adventures in Darkest Africa” among Herbert's juvenilia. Yet Herbert's story aligns with the historical record, a record which fills out the story of “Indian Henry” in a less bucolic, though more plausible, way.

The Hoh are a small band of Quileute people from the Olympic Peninsula on Washington State's west coast. Their early twentieth-century Indian rolls contain only one Henry: a fisherman named Henry Martin, known also as Han-daa-sho, Han-duo-sho, or H'an-Daa-Shoh, and identified racially on the federal census as “full blood Quileute.”Footnote 21 Martin was born around 1890, the right time to have been in his forties when he met Herbert in the 1930s. The 1920 federal census records Martin as living on the Quileute reservation at La Push with his wife, Bolítsa, and her parents, Tqlakas and Bolíłaks Eastman.Footnote 22

The Eastmans were a couple with a powerful spirit identity – Tqlakas was a gifted elk hunter and one of the Olympic Coast's most respected fur sealers. Henry Martin's Quileute name, Han-daa-sho in its various spellings, suggests he shared that quality with his in-laws. The Quileute language is highly unusual in its lack of nasal m and n sounds, those phonemes having shifted respectively to b and d long ago, according to the anthropologist Jay Powell. The only nasal phonemes left, mb and nd (as in Han-daa-sho) refer to spirit powers. That Martin received the name Han-daa-sho indicates that he “was a recognized individual with a powerful guardian spirit,” Powell notes.Footnote 23

What carried Henry Martin from living with an eminent family at La Push to an old smokehouse on Fox Island, eager for the company of a teenager? Henry Pettitt's 1950 ethnography, The Quileute of La Push, 1775–1945, tells a story of dissolution. Not long after the US government set aside a square mile at La Push for the Quileute in 1856, a land-hungry white trader burned the Quileute village there to the ground. Quileutes held their ground and rebuilt their homes, but starting in the 1910s they experienced “general white pressure” from Forks, the nearby logging town.Footnote 24 Relations with the federal government deteriorated. Meanwhile, alcohol flowed into La Push from Forks.

Census records, Indian rolls, and even sympathetic ethnographies such as Pettitt's are limited in what they can say about Indigenous experiences. They offer outsiders’ glimpses, not detailed internal accounts. Still, one page of Pettitt's book casts light on Henry Martin's life. As Pettitt explains, the federal government sent an agent to La Push as a multipurpose functionary: teacher, judge, and police officer. In that last capacity, the agent monitored alcohol traffic by stopping cars entering La Push at night. In 1927, he arrested Martin and, the next day, as judge, sentenced him to sixty days’ labor. Martin, consulting a lawyer, concluded that this was illegal, so he refused to serve his sentence. Shortly after, another Quileute man continued Martin's defiance by refusing to stop his car when the agent commanded. The agent “fired several shots at the tires,” Pettitt writes.Footnote 25

Such episodes of governmental abuse prompted Quileute parents to leave La Push, triggered the Indian school's closure, and led to difficult days, Pettitt further explains. Conditions there were “extremely bad,” a visiting governmental representative reported in 1929, with a collapse of all state services and a rise of alcoholism.Footnote 26 The next federal census, from 1930, found Henry Martin living elsewhere, on the nearby Quinault reservation.Footnote 27 It's not hard to imagine how the hardships of the Quileute community and his brushes with the law might have led Martin to move once again, perhaps after his wife's departure, to nearby Fox Island, where he met Herbert and hinted at his “troublesome” past.

There is reason to think that Martin meant a great deal to Herbert. Herbert's fiction contains numerous accounts of whites, usually boys, befriending Native men and learning their ways. The first story Herbert published under his own name told of an Alaska Native guiding a white sergeant through the perilous landscape.Footnote 28 Similarly, Dune features a fifteen-year-old offworlder, Paul Atreides, who masters the desert planet's inhospitable environment with the help of the native-born Stilgar. In a later novel, Soul Catcher (1972), Herbert captures the relationship even more precisely. In the novel, a Hoh man, Katsuk, kidnaps a thirteen-year-old white boy, befriends him, and teaches him to live in the forest – imparting the specific lessons Martin had taught Herbert.Footnote 29

In Soul Catcher, Katsuk seethes at the whites who stole his people's land and raped his sister. We don't know if Martin spoke this way to Herbert, but Herbert came to view settler colonialism critically. As a newspaperman in Santa Rosa, Herbert used a review of a Jimmy Stewart western to indict the federal government for having “violated the humane provisions of the Genocide Convention by acts against more than 11 Indian nations.” “We used whiskey, broken promises, class distinction, lies, subterfuge, indirection, half truths, and more whiskey,” he wrote. Herbert particularly noted the “avaricious and conscienceless whites, including the army and the Indian Service,” who had burned Indians’ homes and killed their babies.Footnote 30

This was not a normal way to review a western in 1951. These were not normal views for white journalists to hold. It was a hint that the young writer would be unusually open to Indigenous perspectives.

If Herbert was open to Indigenous perspectives, he was also open to imperial ones. In the 1950s, he worked in politics, always for Republicans. He first went to Washington, DC in the employ of the US Senator Guy Cordon of Oregon. The pro-business, pro-military, and anti-labor Senator was “bedrock conservatism's standard bearer for the state,” writes the historian Jeff LaLande – Richard Nixon stumped for him.Footnote 31 Much of Cordon's career was dedicated to wresting timber-rich public lands away from the federal government. He opposed the large-scale Columbia Valley Authority, which aimed to provide electricity via hydroelectric dams, as part of a communist “red flood” overrunning the world.Footnote 32 Mainly, he feared that the dams would interfere with logging.

“My father jumped at the opportunity to join Cordon's staff,” Brian Herbert has written.Footnote 33 And when Frank Herbert did, he encountered the United States’ territorial empire. Cordon was the chair of the Senate's Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, which supervised the overseas territories. He traveled regularly to Hawai‘i, observed the July 1946 atomic tests at Bikini Atoll, and nearly died in a plane crash visiting Micronesia. Cordon also took great interest in the submerged lands the United States claimed off its coasts. As one of his aides wrote, “Our new empire is the continental shelf.”Footnote 34

That aide was Frank Herbert. He researched the underwater empire extensively for Cordon.Footnote 35 He also drafted, under his own name, a gushing article about the seabed's imperial possibilities. The “scramble for riches under the sea” would be, Herbert predicted, “our modern-day land rush.” Oil, natural gas, and rare minerals glimmered over the horizon of “this new frontier.” The fish, he warned, “had better move over”; humanity was claiming those resources. “We have an empire to develop.”Footnote 36

This aquatic imperialism fed straight into Herbert's first novel, Dragon in the Sea (1956). In it, he imagines the Cold War becoming a duel over resources. The United States feels a “pressing need for oil,” but shortages have required an “almost interminable list of regulations on oil conservation.”Footnote 37 The solution is offshore drilling, and the plot follows a submarine crew trying to tap a rich oil reservoir off the enemy's coast. The novel, a thriller, plunges the reader deep into the underwater frontier.

Before arriving in DC, Herbert had set stories in the Territory of Alaska.Footnote 38 Working in politics only deepened his interest in the overseas territories. Guy Cordon's secretary, Dorothy Jones, had lived in American Samoa, and Herbert became “especially obsessed” with moving there, his son wrote. Herbert aggressively pressed his contacts for a colonial post in American Samoa. He had many contacts to press. Stewart French, the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee's chief counsel, was “a personal friend” whose home Herbert had visited multiple times, according to Brian Herbert. Douglas MacKay, the Interior Secretary, who administered the territories, was a longtime acquaintance.Footnote 39

Herbert shipped governmental material on American Samoa and its environs back home for study. “He called Samoa ‘paradise,’ and showed us romantic color photographs from books and magazines of palm trees, thatched huts and sailing boats,” remembered his son. It doesn't seem that Herbert had a plan of what he might accomplish for the colony so much as a dream of the lackadaisical life he might lead there. In this, he partook in a Pacific sort of orientalism, seeing the colony as a space of uncomplicated leisure.Footnote 40 This was the imperialist's-eye view, alert to the sensual possibilities of the United States’ island empire but blind to its violence and exploitation.Footnote 41 Yet if his vision of American Samoa was blurry, his desire to relocate there was serious. He came “very close to getting the post,” he claimed, and was bitterly disappointed when he didn't.Footnote 42

His dream of an easy life in the colonies dashed, Herbert still “envisioned himself in a remote tropical village, pounding out a literary masterpiece on a manual typewriter,” his son has written.Footnote 43 Herbert had spent time in Mexico before, so when his American Samoa plans collapsed, he packed an automatic pistol, loaded his family into a car, and drove south to Tlalpujahua, a small mining town in Michoacán, where he lived for the better part of a year in 1955–56.

Herbert wrote two unpublished chronicles of his Mexican sojourn. Yet as neither is in his papers, the only available account comes from his son, who had access to both chronicles plus his mother's journal. The story Brian Herbert tells casts his father as a science missionary. Although the locals did not immediately welcome the Herberts, things changed when the curate came down with a grave infection, which Frank treated with sulfa drugs and antibiotics, possibly saving the man's life. “Quite suddenly Frank Herbert became a renowned wise man in those parts,” Brian has written. “Villagers consulted him on important matters and referred to him affectionately as ‘Don Pancho.’” Frank used his newfound authority to spread the gospel of scientific agriculture, translating USDA literature and showing his neighbors how to replenish the soil, prune, and spray trees.Footnote 44 When the Herberts left Tlalpujahua in 1956, “the villagers staged a big daytime fiesta in honor of my father.”Footnote 45

Much like Herbert's story about “Indian Henry,” this tale has a boastful, literary quality. It resembles widely read Cold War accounts – many fictional or fabricated – of US scientific saviors dispensing medicine and agricultural wisdom to the global South's grateful villagers.Footnote 46 This was the age of Tom Dooley, the celebrated “jungle doctor” who bragged of having won hearts and minds in Vietnam with goodwill, medical aid, and DDT powder. To be sure, the resemblance of Herbert's story to others in the air doesn't necessarily make it false. Still, it's hard to imagine a novelist from the Pacific Northwest, armed with only a few pamphlets, contributing much to the agricultural practices of central Mexico.

Whatever happened in Tlalpujahua, the orientation of Herbert's thought by 1956 is clear. He worked enthusiastically for a pro-logging Senator and championed opening a new frontier via offshore drilling. He entertained fantasies of a languorous life in the South Pacific and sought a colonial post there. And he understood himself, in Mexico, as a modernization missionary, spreading the gospel of US science and technology. In all these ways, Herbert engaged closely with US empire. It was an empire he was ready to serve.

Had Herbert published Dune in 1956, it might have resembled the Foundation trilogy by Isaac Asimov, written as short stories in the 1940s and published as novels between 1951 and 1953. In it, Asimov told of a technocratic society reestablishing a galactic empire by science, commerce, and secular missionary work.Footnote 47 Herbert praised Asimov's “beautifully constructed stories,” which seemed to reflect his own worldview at the time.Footnote 48

But Dune as Herbert published it starting in 1963 was nearly the opposite of Foundation.Footnote 49 It shares a setup with Asimov's books: a new empire's origins on the galactic periphery. Yet Dune's heroes are jihadists guided by mystical visions who conquer the galaxy by force, not cool-headed scientists who win it by technology and trade. Where had this come from?

Dune's birthplace is usually located in Florence, Oregon. There, in 1953, Herbert visited a USDA's Soil Conservation Service project to control the migration of sand dunes by planting grasses. Herbert was struck by the thought of those dunes moving “in waves analogous to ocean waves – except that they may move twenty feet a year instead of twenty feet a second.” Such slow swells of sand had menaced settlements for millennia, but Herbert believed that the Oregon scientists had won an “unsung victory” in humanity's long fight against them.Footnote 50 He began to research deserts in preparation for a novel set on a planet of dunes.

The Oregon dunes’ influence is plainly visible in Dune. In undated drafts of the novel, Herbert gives ample space to “Dr. Bryce Kynes,” an offworld expert in “dry land biology” who seeks to terraform the desert planet, Arrakis.Footnote 51 Kynes teaches the local population, the Fremen, to plant “mutated poverty grasses” at the dunes’ edges.Footnote 52 Despite working with the Fremen, Dr. Kynes stands apart from them, priding himself on “being a scientist to whom legends were merely interesting clues to cultural roots.”Footnote 53 Dr. Kynes is “a specialist in fine print, a mind like an official timetable.”Footnote 54 In this “man of science” from the drafts, one sees a clear reference to the Oregon ecologists, and perhaps a nebbish version of Herbert himself in Tlalpujahua.Footnote 55

Yet, by publication, Dune was no longer a story about a clever ecologist. First, Herbert shrank Kynes's role. Second, he made Kynes born on Arrakis – an offworlder's child who has “gone native” and is known also by his Fremen name of “Liet.”Footnote 56 Third, even the half-Fremen version of the character, “Liet-Kynes,” struck Herbert as an imperfect hero, and so he killed him off midway through the novel. Liet-Kynes's death was the “turning point of the whole book,” Herbert explained; Liet-Kynes represented “Western man” who “lived out of rhythm” with Arrakis's environment.Footnote 57 In his last moment, just before dying in the harsh desert he'd sought to tame, Liet-Kynes realizes that he and “all the other scientists were wrong.”Footnote 58 Control of Arrakis then passes to Paul Atreides, otherwise known as the prophet Muad'Dib, who leads not by science but by drug-induced visions.

It's easy to understand how visiting the Oregon dunes helped Herbert imagine an ecologist terraforming a desert planet. What's harder to see is where Herbert acquired his newfound skepticism of science and “Western man.” For that, it helps to turn to a less-explored origin story of Dune. Standing at Herbert's side while he pieced together his novel was his best friend, Howard Hansen, a vocal environmentalist. And Hansen, like Herbert's childhood influence Henry Martin, had lived on the Quileute reservation at La Push.

Howard Hansen, also known as cKulell, was not an enrolled member of the Quileute Nation. He had been raised from birth at La Push by various Quileute families, yet they described him, the anthropologist Jay Powell has recalled, as having “suddenly appeared” there. With neither father nor mother publicly identified, he was “raised surrounded by questions,” though his growing resemblance to a member of the tribe as he aged bolstered theories as to his parentage.Footnote 59 Whoever his parents were, Hansen lived his life “based on Quileute Indian teachings,” he wrote.Footnote 60 After displaying an early affinity for spiritual matters, he studied with the elder Lester Payne, who helped train him as a historian. “I learned Quileute mythology and legend, learned to drum and sing Spirit songs of power; to analyze Life,” Hansen remembered.Footnote 61 For a small and imperiled community, he was to be a cultural repository.

Hansen met Herbert shortly after the Second World War at a piano recital in Seattle. “I was just off the reservation and pretty wild,” Hansen recalled. “Maybe that's why Frank liked me.”Footnote 62 Whatever the attraction, the two became close, living briefly together on a houseboat and talking of sailing the world together. “Of my father's many male friends, none touched his heart like this one,” Brian Herbert wrote.Footnote 63 Indeed, Frank Herbert and his wife Beverly made Hansen Brian's godfather.

Hansen was, like Herbert, a writer. While Herbert developed Dune, Hansen was preparing his own work, Twilight on the Thunderbird (started in 1958 but published only in 2013). It told of how the Quileute reservation at La Push had changed during his lifetime. La Push, sited amid the Olympic Peninsula's rare temperate rainforests, is one of the wettest places in the contiguous United States, but Hansen noted how logging from the nearby white town of Forks was rapidly transforming it. “The raping of Forest between Village and Forks was changing everything,” he remembered. Familiar forest locales had turned to “mud” or “baked earth.” An impressive tunnel of Sitka spruces, capable of blocking out the sun, had been converted into rows of “huge stumps.” It was a “massacre,” Hansen wrote. The loss of the land, he feared, heralded the loss of traditional Quileute life.Footnote 64

Hansen's emphases on cataclysm and on the close connection between land and culture distinguished his environmentalism from the genteel Sierra Club conservationism that still reigned in the 1950s. But he was not alone. Across the US West, Native communities experienced mid-century environmental transformations as existential peril, not just threats to their recreation areas.Footnote 65 Historians have documented how much the more radical environmentalism of the 1960s and 1970s drew on Native experiences. Sometimes, Indians appeared in environmentalist thought merely as stereotypes (e.g. the “Crying Indian” who became a 1970s antipollution mascot). At other times, though, the collaboration between Native and non-Native environmentalists was productive and substantive.Footnote 66

Herbert worked for a pro-logging Senator, championed offshore oil drilling, and then took a job with a Tacoma timber firm, so initially his environmentalism was halfhearted at best.Footnote 67 But he read Hansen's manuscript and offered editorial advice.Footnote 68 According to Brian Herbert, “an Indian friend” gave Hansen a book on ecology, which Hansen then passed on to Frank Herbert. The book spoke of the planet's “decimation,” a prospect Hansen took seriously. “White men are eating the earth,” he told Herbert. “They're gonna turn this whole planet into a wasteland, just like North Africa.” Herbert, already thinking of his novel in progress, agreed, responding that the world would become a “big dune.”Footnote 69 Herbert chose the word dune for his title, he later reflected, because it sounded like doom – the Earth's likely fate.Footnote 70

Hansen's views sparked something in Herbert. Dune's environmentalism, according to Brian Herbert, was “based … in part” on discussions Frank Herbert had “with his best friend, Howard Hansen.”Footnote 71 Hansen himself “felt he contributed many of the ideas” of the novel, his wife, Joanne Hansen, remembered. “They explored the idea of Dune, a planet without water. They spent a lot of time talking about that.” Ultimately, she continued, Howard believed that Dune contained numerous of his ideas, which were “expanded on by Frank.”Footnote 72

Such contributions probably went beyond environmentalism. Dune is notable not just for exploring planetary ecology but for its sympathetic treatment of the native population of Arrakis. Paul Atreides defeats the imperium by allying with the Fremen of the desert. And there are good reasons to think that Herbert's portrayal of the Fremen was informed by his conversations with Henry Martin and Howard Hansen, two spiritually inclined members of the extended Quileute community.

At first glance, Dune's Fremen appear to have nothing to do with Native Americans. Herbert adorns them with markers from the Arab and Muslim worlds: they use terms like Mahdi and jihad, quote the Qur'an, and speak a language that resembles Arabic or Turco-Persian.Footnote 73 Moreover, Herbert's account of Paul's leadership of the Fremen drew visibly on T. E. Lawrence's well-known Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926), in which Lawrence described living with, dressing like, and fighting alongside desert rebels in the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The similarities were hard to miss, especially as Lawrence of Arabia (1962) had won the Oscar for best film mere months before Dune first appeared in serial. It is thus tempting to read Dune, as some scholars have, as a novel for the age of decolonization – a story of anticolonial nationalism, albeit with a white savior at the fore.Footnote 74

Yet Herbert had never been to the Middle East or North Africa, nor does his nonfiction feature much engagement with Third World anticolonial struggles.Footnote 75 Dismantling empires and replacing them with nation-states was not an abiding concern of his, especially given his close connections to the US empire. The five Dune sequels that he published from 1969 to 1985 tell of successive imperial wars, but nowhere do they affirm national independence or the abolition of international inequalities.Footnote 76 Quite the opposite. By the later novels, Herbert's heroes are defending the “core of the Old Empire” against “ravenous hordes” from the galaxy's periphery.Footnote 77 In his own country, Herbert had little patience for decolonization's liberal and left-wing champions. He loathed John F. Kennedy, the President most supportive of Arab nationalism, and defended Richard Nixon. He rolled his eyes at protesters who demanded “Power to the People,” insisting firmly that “all humans are not created equal.”Footnote 78

The radical politics that Herbert did engage with were not Third World, but Fourth World. The distinction, as articulated by Secwépemc leader George Manuel in the 1970s, was between rising peoples in Africa and Asia adopting Western technologies and forming Western-style nation-states (the Third World) and the “Aboriginal World” which did not seek to form nation-states or imitate the West (the Fourth).Footnote 79 Whereas Third World movements principally sought to seize control of foreign-ruled governments and win equality within the international system, Fourth World ones aimed for land rights, cultural preservation, and autonomy from national governments. As Audra Simpson has observed, the Third World mission – inculcating national solidarity within borders drawn awkwardly and often arbitrarily by distant imperial governors – held little force in the Fourth World. There, Indigenous nations preceded Western contact and had remained intact for centuries – sometimes cutting stubbornly across colonial borders.Footnote 80 Fourth World struggles, in other words, traveled a different path than Third World ones.Footnote 81

That path passed right by Herbert's door. Though he had at best an armchair understanding of Third World nationalism, campaigns for Indigenous recognition and self-determination were erupting all around him. And he took a clear interest. By the late 1960s, on the strength of Dune's sales, he could finally leave journalism to write novels full time. His first Dune sequel, Dune Messiah, came out in 1969, with the promise of another to come. Yet at this long-awaited moment of literary success, Herbert stopped the lucrative Dune train and departed from science fiction entirely to write a novel he claimed had been “stirring inside him” since his childhood.Footnote 82 This was Soul Catcher (1972), about the collision between Indigenous and European ways of life in the Pacific Northwest. It was set on the Olympic Peninsula, on the traditional Quileute lands.

Herbert sought federal funding to write the novel. He wanted to film and tape Native rituals, legends, and songs from the Northwest Coast, with Hansen as his research assistant. He never got funded, but he still made recordings at a number of reservations, which helped him draft Soul Catcher in 1970. Before he published it, however, Herbert “attended a seminar conducted by Native Americans, at which they expressed their anger toward white society,” according to his son. Hearing this, Herbert felt a “sinking sensation” and concluded that his manuscript hadn't captured the “extent of Indian outrage.”Footnote 83

Herbert did more than attend a seminar. In March 1970, months after the Native seizure of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, the United Indians of All Tribes occupied Fort Lawton in Seattle. It was a high-profile event, and Herbert rushed to interview one of its leaders, Bob Satiacum (Puyallup). “We have awakened our world to the countless injustices done to Native Americans,” Satiacum told him. Herbert noted that the first use Satiacum's group proposed for the fort's land was an environmental display to “help teach whites how to stop destroying the earth” (Herbert would soon establish his own “Ecological Demonstration Project” on his farm).Footnote 84 He published his interview in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and, later that year, wrote another sympathetic piece, reporting the views of Tlingit and Ojibwe activists regarding federal land policy.Footnote 85

Feeling that his novel hadn't fully registered such attitudes, Herbert burned the Soul Catcher manuscript and rewrote it.Footnote 86 The version he published in 1972 tells of a Hoh man, Katsuk, whose sister has been raped by drunken loggers, leading her to commit suicide outside La Push (this was based on a real event in western Washington). Katsuk, imbued with “Red Power” ideology, takes revenge by kidnapping a federal official's thirteen-year-old son, David, and, after teaching David to live in the forest, killing him.Footnote 87 Howard Hansen was discomfited by David's murder, which he felt was not “the way the Quileute people would have acted,” Joanne Hansen remembered.Footnote 88 But from Herbert's perspective, the killing had a personal meaning, given how closely the Katsuk–David relationship resembled that between Henry Martin and a young Frank Herbert. In offering the “immigrant invader” David up for sacrifice, Herbert was symbolically martyring himself, a descendant of white settlers, to his understanding of the Fourth World cause.Footnote 89

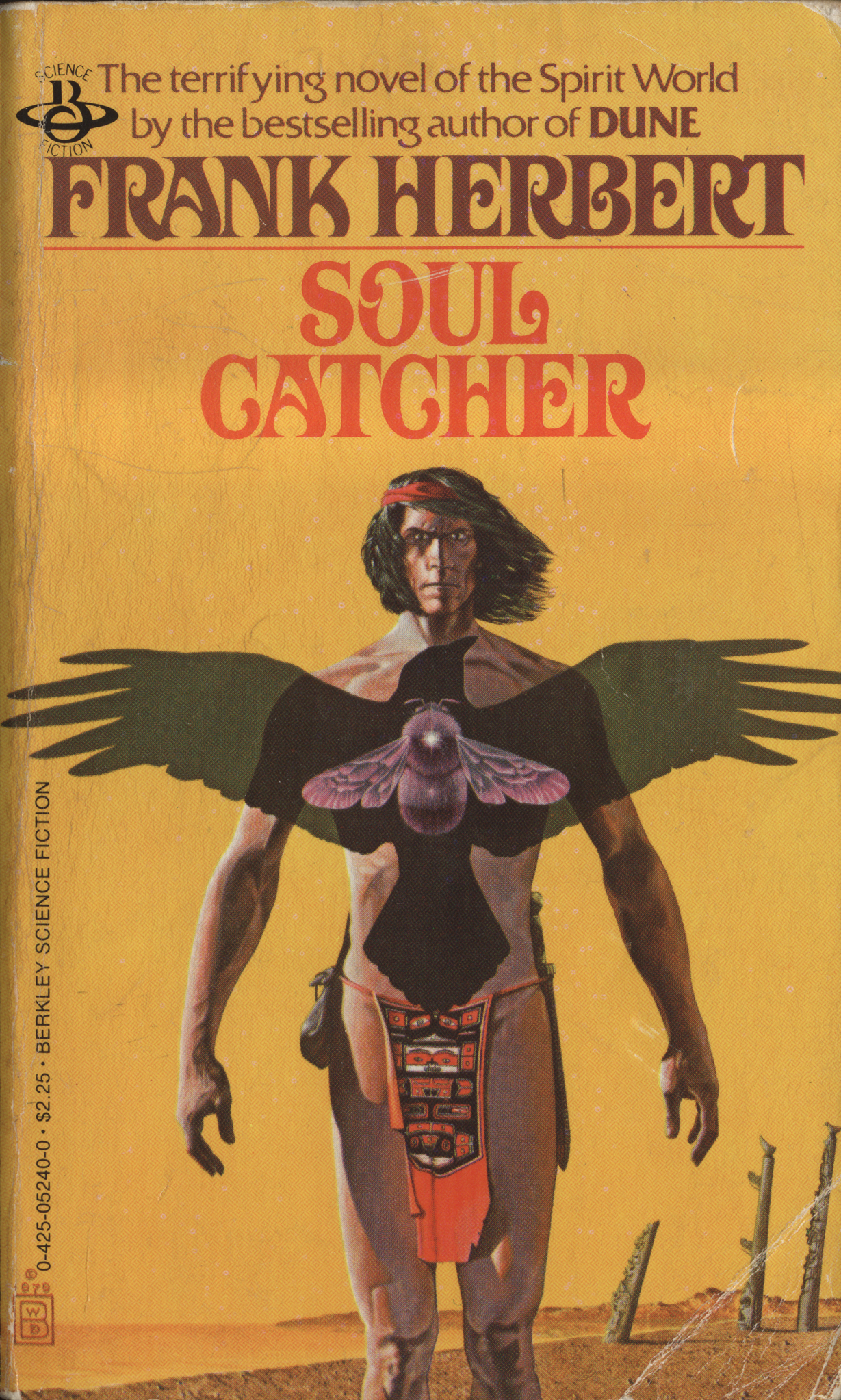

Figure 1. Cover of Frank Herbert's Soul Catcher (New York, Berkley Books, 1979; first published New York: G. P. Putnam's, 1972; subsequently reprinted 1980 and 1981). Despite the depiction of the desert – presumably an attempt to capitalize on Dune's success – Soul Catcher was set in one of the country's rainiest areas, the forested Quileute lands in western Washington.

Herbert kept going. Confident that Soul Catcher's slow sales would accelerate, he drafted another Indian novel, Circle Times, based on events in the Pacific Northwest and treating the Indian view of the universe. It was a lengthy, “involved work,” his son has written, one Herbert couldn't sell publishers on.Footnote 90 That he would devote so much energy to a long, unmarketable novel about Native life at a time when editors were begging for Dune sequels shows how seriously he took Indigenous matters.

Did Herbert's interest in Indian societies shape Dune? With Martin, Hansen, Soul Catcher, and Circle Times in mind, it becomes easier to hear the resonance between the Fremen and the Native peoples of North America, particularly the Quileute. The Fremen, Herbert writes, are not an intensively colonized population so much as a people of the fringes, under no one's command and “marked down on no census” (most Indians were excluded from the US Census until 1890).Footnote 91 Though they have taken on some beliefs from Bene Gesserit missionaries – much as the Quileute had adapted Shaker practices – they maintain a distinct way of life.Footnote 92 They make little use of imperial technologies and live as a persecuted people in the desert, where they practice their religious rites involving psychedelic drugs. They organize their lives around the giant sandworms that swim through Arrakis's desert waves, not unlike the whales that Quileutes once harpooned off the Pacific coast.Footnote 93

The Fremen ethic is one of conservation and ecological balance: they avoid wasting resources and regard offworlders’ extractive ambition with scorn. Herbert writes of this with great sympathy. Indeed, Paul's induction into the Fremen worldview is one of the most memorable parts of Dune. In the next two novels in the series, Herbert explores what happens when the Fremen lose their land ethic. As the desert retracts and sandworms die, the Fremen adopt imperial ways, grow dependent on pills, and become “Museum Fremen,” “degenerate relics” of “once-proud warriors.”Footnote 94 If Hansen had presented Herbert with the specter of social dissolution when one of the wettest parts of the country, La Push, dried out from logging, Herbert responded with a saga about the cultural erosion endured when the driest planet loses its desert. Herbert's Dune was Hansen's Twilight on the Thunderbird with wet and dry inverted.Footnote 95

As Herbert told his son, the Dune character he most identified with was Stilgar, a Fremen tribal leader. Brian Herbert had expected his father to pick Paul but then realized that “Stilgar was the equivalent of a Native American leader in the story – a person who defended time-honored ways that did not harm the ecology of the planet.”Footnote 96 Seeing this, Brian understood why his father chose Stilgar.

Up through 1956 or so, Frank Herbert had been involved in US imperial projects in many ways. Yet his childhood connection with Henry Martin and close adult friendship with Howard Hansen allowed him to glimpse empire's destructive capacity. He'd seen himself as an agent of modernization in Tlalpujahua, yet he knew what the loss of traditions was doing to the Quileute community. He'd advocated for resource extraction, including logging, but Hansen showed him how damaging this had been to western Washington.

These tensions animated Herbert's fiction. Those seeking to pin down Herbert's politics have been vexed by Dune's ambivalence. The six books tell of successive campaigns to transform Arrakis and control the galaxy, yet each revises the principles of the preceding installments. Taken as a whole, the saga was, in Herbert's worlds, an “Escher lithograph.”Footnote 97 Rather than resolving, its themes recur, mutate, and twist into paradox.

The first such theme is scientific ecology. Herbert initially presents Arrakis as a site of colonial extraction. It's the sole source of the all-important “spice melange,” the raw material that enables interstellar travel. Yet mining spice from the inhospitable desert proves to be no easier than drilling oil from the continental shelf, which Herbert had described in Dragon in the Sea and his nonfiction writing. Hope comes from the ecologist Liet-Kynes, who promises to terraform Arrakis, thus enabling its development. He spreads “ecological literacy” among the appreciative Fremen, much as Herbert had boasted of teaching scientific agriculture in Tlalpujahua.Footnote 98

Yet Liet-Kynes dies in the desert, cursing science with his final breath. Herbert had grown suspicious of top-down development projects. Later in life, he would decry the United States’ “addiction to science” and habit of building large hydroelectric dams to develop Asia.Footnote 99 He never disavowed technology entirely – Herbert was an avid tinkerer who wrote an early user's guide to computers.Footnote 100 Yet his discomfort with modernization imposed by outsiders was palpable.

After Liet-Kynes, Herbert puts forth Paul Atreides, an offworlder from the watery planet of Caladan. Paul shares Liet-Kynes's terraforming ambitions but not his commitment to science. Whereas Liet-Kynes secures the Fremen's allegiance by teaching them ecology, Paul wins their support by becoming a religious leader, Muad'Dib, and fulfilling Fremen prophecies concerning the messiah. With a Fremen army behind him, he attacks the imperium, asserting Indigenous values over metropolitan ones and restoring control of the spice lands to the Fremen. As a prophet, Paul preaches against “manifest destiny,” warning of its “demoniac side.”Footnote 101

This is a far cry from Herbert in the 1950s, who wrote excitedly of conquering frontiers, spreading science, and ruling empires. The passage from Liet-Kynes to Paul marks a shift in the novel from the scientific ecology of the Oregon dunes to Howard Hansen's Fourth World environmentalism. Yet, even as Herbert rejects aspects of imperialism, he does not relinquish it wholly. First, he centers the action on Paul, an offworlder, rather than on any of the Fremen. Paul adopts Fremen ways but doesn't drop his Atreides identity. He is the outer-space equivalent of a white savior figure, much as Herbert saw himself in Mexico. Second, though Paul challenges the Emperor, he never challenges empire itself. “I rule on every square inch of Arrakis!” is his rallying cry to the Fremen. “This is my ducal fief whether the Emperor says yea or nay!”Footnote 102 The first novel ends not with Paul dismantling the galactic empire but seizing its throne, the ruler of Arrakis and far beyond.

Paul's defeat of the Emperor is a jubilant moment. Yet Herbert troubles Paul's triumph by giving premonitory flashes of what comes next. Paul, gifted with prescience, envisions “fanatic legions following the green and black banner of the Atreides, pillaging and burning across the universe in the name of their prophet Muad'Dib.”Footnote 103 Herbert also, in the novel's appendix, ominously describes Paul's arrival as the moment when Arrakis was “afflicted by a Hero.”Footnote 104

It's easy to tune these brief omens out. “Dune was set up to imprint on you, the reader, a superhero,” Herbert reflected.Footnote 105 Readers who took the bait and ignored the warnings were punished by the series’ second volume, Dune Messiah (1969), which told how Paul's Fremen revolt had turned genocidal. His forces had “killed sixty-one billion, sterilized ninety planets, completely demoralized five hundred others,” and wiped out forty religions. Paul, looking back on his legacy, compares himself to Adolf Hitler and then laughs on realizing how far he has outstripped the Führer.Footnote 106

There was, Herbert felt, a lesson here. Hidden within Dune's “mess of pottage” was a “pot of message,” he told NBC's Bryant Gumbel. And that concealed message? “Don't trust leaders.” Herbert had presented Paul as “really an attractive, charismatic person,” he explained, in order to lure his readers into a literary ambush.Footnote 107 “There is definitely an implicit warning, in a lot of my work, against big government and especially against charismatic leaders.” Herbert's prime example was John F. Kennedy, whom he deemed “one of the most dangerous presidents this country ever had.”Footnote 108 Dune debuted in serial a month after Kennedy's assassination, and Paul's resemblance to the young President was notable.Footnote 109

Alongside Herbert's warning about big government came one about Native life. As the Fremen leave their homeland, Arrakis, to conquer the galaxy, they degenerate. The Fremen leader Stilgar explains how they've lost traditions and seen their “old beliefs crumbling.”Footnote 110 Paul's son Leto II, thinking along similar lines, reflects on the Fremen plight:

Before the glowglobes and lasers, before the ornithopters and spice-crawlers, there'd been another kind of life: brown-skinned mothers with babies on their hips, lamps which burned spice-oil amidst a heavy fragrance of cinnamon, Naibs [tribal leaders] who persuaded their people while knowing none could be compelled. It had been a dark-swarming of life in rocky burrows …

A terrible glove will restore the balance, Leto thought.Footnote 111

This is a modernization narrative in a tragic key. With unsubtle racial markers, Herbert suggests that the Fremen are unsuited for a future illuminated by glowglobes and lasers. The “dark-swarming of life” – it's hard not to hear echoes of decades-old racism in that phrase – identifies the dimly lit caves with “brown-skinned” people. Yet the problem in Leto's view isn't with the Fremen so much as with the ambition to modernize them. Rather than pulling them into the light, he resolves to “restore the balance” – to force them back into their old ways with a tyrant's “terrible glove.”

This loss of Indigenous traditions haunts the novels, much as it does Howard Hansen's Twilight on the Thunderbird, which Herbert had read in manuscript. Yet there is an important difference. For Hansen, the threat to Native life was white encroachment and land theft. For Herbert, it's Fremen strength. Though Herbert writes with palpable affection for the Fremen as persecuted desert dwellers, he seems unable to imagine how they might gain power without losing their admirable qualities. Their convictions, once taken off planet, become “religious butchery”; their culture becomes a hollow shell.Footnote 112 Herbert's notable sympathy for Indigenous people thus comes with a condescending “stay-in-your-lane” injunction. Once the Fremen move from weakly resisting the imperium to controlling it, their jihad becomes, in his telling, a nightmare of decolonization.

In Children of Dune (1976), Herbert introduces a third campaign, Leto II's “Golden Path.” Like his father Paul, Leto leads a brutal, galaxy-subjugating crusade: the “Typhoon Struggle,” which makes Paul's sixty-one-billion-victim jihad look like a “summer picnic.”Footnote 113 With an iron grip on the spice supply (the “terrible glove”), Leto grinds the galactic economy to a halt: no travel, no growth, no political change – just millennia of tyrannically enforced stasis. Herbert's readers would have thought immediately of the oil crisis that had recently paralyzed Western economies but, in Herbert's telling, the event is salutary. Leto reverses the terraforming of Arrakis, drying its croplands and returning its forests to “great moving dunes.”Footnote 114 Many starve, leaving only the “hardiest and most brutal,” and the surviving Arrakians rekindle their vibrant religious traditions.Footnote 115

The purpose of Leto's anti-modernization quest is twofold. First, by ruling tyrannically, he seeks to be a “myth-killer.”Footnote 116 The myth Leto aims to destroy is that of government, which he regards as a “disease.”Footnote 117 In oppressing the universe for millennia, he'll teach humanity a “lesson their bones would remember”: never to trust leaders.Footnote 118 In this, Leto resembles Richard Nixon, whom Herbert believed “taught us one hell of a lesson.”Footnote 119 Nixon, Herbert half-joked, was “my favorite president in recent years” because “he taught us to distrust government.”Footnote 120

Leto's Golden Path, second, seeks to restore Fremen virtue. By destroying the interstellar economy and making Arrakis a desert again, Leto drives its inhabitants back into the Fourth World.Footnote 121 It is perhaps relevant that, by this time, Herbert had sold his home in Washington State and moved to Hana, a hard-to-access part of Maui with a large population of Native Hawaiians. “I'm one of the natives now,” he announced proudly.Footnote 122 In Herbert's case, though, life in rural Polynesia was counterbalanced by frequent trips to the mainland, where his book was being made into a heavily promoted film.

Leto dies at the end of God Emperor of Dune (1981), but his Golden Path continues. In Heretics of Dune (1984), Leto's acolyte, the missionary Darwi Odrade, comes to rue the “modernization” of Arrakis's cities – the loss of ritual and the rise of technological convenience – and lights upon another planet to turn into a desert.Footnote 123 At the end of the series, Odrade's successor, Sheanna Brugh, a tough Arrakis native, sets out on her own galactic transformation campaign. Herbert never reveals Sheeana's plan; readers learn only that the “Sheeana future” will offer “bitter medicine.” “Some will choke on that medicine,” the novel concludes, “but the survivors may create interesting patterns.”Footnote 124 Herbert died before finishing the saga.

Liet-Kynes, Paul, Leto II, Odrade, Sheeana – the parade is long, violent, repetitive, and confusing. Rather than resolving the tensions in his politics, Herbert experimented, combining and recombining elements. He never let go of empire, he never lost interest in Indigenous life, and he never reconciled the two. Though Herbert reveled in decoding the moral of the first Dune novel, he refused to explain the “complex mixture” of the later ones. “You find your own solutions,” he advised, “don't look to me.”Footnote 125

Herbert's epic tale of empire and Native life, set 25,000 years in the future on distant planets, was not the product of a fertile imagination alone. It flowed from Herbert's imperial engagements, working in politics and living in the Pacific Northwest. Herbert had been an imperialist and a champion of Native rights, a technological enthusiast and a back-to-the-lander. Dune was a way of projecting these unreconciled commitments – many derived from the Pacific Northwest – onto a galactic scale.

The Dune series stretches over ten thousand worlds and many millennia. Yet it is also arguably the story of a small patch of land over a mere generation. The Quileute reservation at La Push, about a square mile in size, served as a microcosm for Native history, one that informed Herbert's growing engagement with environmentalism and empire.

Curiously, Dune isn't the only franchise featuring La Push. In 2005, the Mormon author Stephenie Meyer published Twilight, the first entry in her best-selling vampire romance series set in the logging town of Forks, Washington. She'd never been to Washington before writing Twilight; she found Forks by looking online for the rainiest place in the country.Footnote 126 Reading further, she learned of La Push and wrote the “tiny Indian reservation on the coast” into her saga, too.Footnote 127 Meyer “latched onto” the Quileute creation legend involving wolves, as she put it, and made the Quileute a race of werewolves.Footnote 128

Quileute characters feature heavily in the Twilight novels and films, which have earned billions. Nordstrom and Hot Topic have offered Quileute-themed clothing as part of their Twilight merchandising. Fans can also pay to tour La Push by bus. But the Quileute Nation has no claim on any of these revenues, and many of its members live in poverty.Footnote 129

A long Quileute shadow thus hangs over two of the most lucrative science fiction/fantasy franchises in history. Yet for all the enthusiasm for Quileute people depicted by white authors as Fremen or werewolves, there's less interest in them as subjects in their own right. There has been talk of making Herbert's Soul Catcher into a movie with significant Indian input. Today, the film is under option, with the country's most prominent Native director, Chris Eyre (Cheyenne and Arapaho), slated to direct. “It's a dark movie, it's a political movie,” as Eyre sees it.Footnote 130 The producer, Dimitri Villard, told Indian Country Today that Howard Hansen was “willing to spend a lot of time on the project.”Footnote 131 But Hansen died soon after, and the film remains unmade. Eyre worries that Soul Catcher's theme of Native vengeance makes it a difficult sell.Footnote 132

Meanwhile, La Push is in dire straits. It is not drying out, as Hansen had feared, but facing floods as the planet warms; increased rain weakens its soil and the deforested land can't hold moisture in place. “Almost every winter now the Quileute reservation is cut off due to extreme flooding,” Chelsie Papiez has written in a climatological study. Large waves batter the coastal community, and the tribal school conducts regular tsunami drills in which children rush from the lower village in search of higher ground.Footnote 133

The irony is painful. In 1958, Hansen, aghast at logging's toll on La Push, warned Herbert that whites were “gonna turn this whole planet into a wasteland, just like North Africa.” With Hansen's input, Herbert wrote a novel, Dune, imagining that. It was a prescient, influential work of environmentalism, describing ecological change not at the scale of a lake or forest but a planet. The tiny world of La Push became a model for the large one of Arrakis, and through Arrakis readers glimpsed what climate change might do to their own planet, Earth. Now the circle is complete. Earth is terraforming, and La Push is drowning.