Introduction

The figures are alarming, and the prevalence of overweight and obesity and the number of people affected have increased in all age groups and will continue to rise over the next decade. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), more than 1.9 billion adults aged 18 and over were overweight, of which more than 650 million were obese. The figures for children are even more worrying, with 40 million children under five years of age overweight or obese and more than 340 million children and adolescents (aged 5 to 19 years) overweight or obese.Footnote 1

Spain is no stranger to this disease; on the contrary, in Spain it has tripled since the 1970s. According to the 2020 European Health Survey in Spain, 16.5% of men aged 18 and over and 15.5% of women suffer from obesity. In the 35 to 74 age groups, the percentage of men suffering from obesity is higher than the previous age group. Regarding overweight, 44.9% of men and 30.6% of women are overweight. The differences between men and women are greater than in the case of obesity, and the percentage of overweight men is higher in all age groups. In fact, for the 65–74 and 75–84 age groups, both men and women have the highest levels of overweight, but in the case of men they represent 51.93% (65–74 years) and 55.46% (75–84 years), while for women they are 41.34% and 41.44%, respectively. This situation represents a public health challenge that is often not recognized as a serious social and health problem. In fact, obesity should be considered an epidemic disease that represents a major public health problem, not only because of the enormous impact it causes on morbidity and mortality, and quality of life, but also because of the large costs, both direct and indirect, that this pathology generates (National Institutes of Health, 1998).

As Figueroa (Reference Figueroa2009) says, overweight/obesity is a disease with a complex origin derived from genetic but also cultural, social and economic factors. In fact, the abrupt increase in overweight/obesity shows a growing trend in both developed and developing countries, in both genders, in all age groups and is mainly due to important changes in the diet of the population, the pattern of physical activity and other socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental factors, all of which have manifested themselves in a process of nutritional transition (fulfilling the model proposed by Popkin (Reference Popkin1993)). However, in relation to the socioeconomic determinants of this problem, what matters more for overweight, educational attainment, or income? Answering this question is a novelty in this type of studies and is the main objective of this work.

Pioneering epidemiological studies that considered the social determinants of health focused mainly on the relationship between malnutrition and communicable diseases with lack of income. Obesity and chronic diseases were mainly related to economic well-being. These conceptions are no longer valid today, and the relationship is quite complex and multifactorial, both in developed and underdeveloped countries and in different ways (Peña and Bacallao, Reference Peña and Bacallao2000). In fact, there are numerous studies that consider that, in addition to genetic factors and income, a wide variety of socioeconomic factors are determinants of the incidence of obesity (Labonté and Schrecker, Reference Labonté and Schrecker2007; Figueroa, Reference Figueroa2009; Antonio-Anderson et al., Reference Antonio-Anderson, Félix-Verduzco and Gutiérrez Flores2020). In any case, authors such as Jolliffe (Reference Jolliffe2011) point out that the severity of overweight has been greater for the poor than for the non-poor. More recently, Templin et al. (Reference Templin, Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi, Thomson, Dieleman and Bendavid2019) show that as countries develop economically, the prevalence of overweight increases in the poorer population, while it remains stable in the higher-income population. The same conclusion was reached by Reyes-Matos et al. (Reference Reyes Matos, Mesenburg and Victora2020) in a study focused on women. According to these authors, overweight is the prevailing problem among the poorest women in poor countries as national income increases.

The problem with the effects of income on overweight is that it is hereditary. As stated by Demment et al. (Reference Demment, Haas and Olson2014), remaining in low income and moving into low income increases risk for adolescent overweight and obesity. But, even when talking about heredity, the works almost always focus on the purely genetic aspects and leave aside its social aspect, which is extremely important in the analysis of social inequality in health. The relative contribution of genetic factors and inherited lifestyles to obesity remains largely unknown (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Power, Logan and Summerbelt1999; Wells, Reference Wells2018, Reference Wells2011). In fact, some studies have shown that the socioeconomic level of the parents is related to that of the children, indicating that there is a certain hereditary transmission of some factors (educational, attitudes, and knowledge about nutrition, body image, etc.) that can condition the socioeconomic level reached by the individual or certain attributes related to it, such as psychological, social, and material well-being (Sobal and Stunkard, Reference Sobal and Stunkard1989; Barker, Reference Barker, Bray and Bouchard2003).

With respect to educational level, an inverse relationship has been observed between cultural level and the prevalence of obesity, such that the lower the level of education the higher the prevalence of obesity. Thus, González-Zapata et al. (Reference González-Zapata, Estrada-Restrepo, Álvarez-Castaño, Álvarez-Dardet and Serra-Majem2011), in their study of more than 105 countries around the world, show a negative correlation between excess weight and the literacy rate (measured as a component of the Human Development Index (HDI). Rodríguez-Caro et al. (Reference Rodríguez-Caro, Vallejo-Torres and López-Valcarcel2016) define four homogeneous levels of education (unfinished primary, primary, secondary and university studies), to obtain that the higher the level of education the lower the level of obesity in the Spanish population, obtaining, in addition, a more pronounced social gradient in relation to educational level than the other socioeconomic variables used (family income and social class). On the other hand, Antonio-Anderson et al. (Reference Antonio-Anderson, Félix-Verduzco and Gutiérrez Flores2020) show how the level of schooling is negatively related to obesity in Mexican adults. However, considering that both income and educational level are key elements that determine the prevalence of overweight, this paper tries to analyse which of the two is more important. The few papers that have focused their analysis on these two factors point out that educational attainment is a stronger predictor than income in explaining overweight (Roskam and Kunst, Reference Roskam and Kunst2008; Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Fankhänel, Riedel-Heller and Luck-Sikorski2019).

In addition to educational attainment and income, many other socioeconomic variables have been analysed as determinants of overweight. In fact, there is a large literature studying socioeconomic factors and their effects on overweight. Starting with age and gender, we see that the prevalence of overweight/obesity increases with advancing age. Specifically, the older the age the higher the prevalence of overweight (Fortich Mesa and Gutierrez, Reference Fortich Mesa and Gutiérrez2019; Kunzova et al., Reference Kunzova, Maugeri, Medina-Inojosa, López-Jiménez, Vinciguerra and Marques-Vidal2020; Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Tavares, Ferreira, Welch, Horta, Cardoso and Santos2021) and this relationship, the higher the age, the higher the prevalence of overweight is shown to a greater extent in women. (Aranceta-Bartrina et al., Reference Aranceta-Batrina, Pérez-Rodrigo, Alberdi-Aresti, Ramos-Carrera and Lázaro-Masedo2016; Du et al., Reference Du, Wang, Zhang, Qi, Mi, Liu and Tian2017). In this regard, it should be noted that we found studies showing that this relationship of prevalence of overweight in older women does not hold true in high-income countries (Antelo et al., Reference Antelo, Magdalena and Reboredo2017; Aranceta-Bartrina and Pérez-Rodrigo, Reference Aranceta-Batrina and Pérez-Rodrigo2018; Kunzova et al., Reference Kunzova, Maugeri, Medina-Inojosa, López-Jiménez, Vinciguerra and Marques-Vidal2020), while in low-income countries this positive relationship does hold true, i.e., in poorer countries it is true that women tend to be overweight at younger ages (Álvarez-Castaño et al., Reference Álvarez-Castaño, González-Zapata and Góez-Rueda2014; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Emamian et al., Reference Emamian, Fateh, Hosseinpoor, Alami and Fotouhi2017).

The literature that explores the analysis of lifestyle and its incidence on overweight shows how sedentary lifestyles, lack of physical activity and junk food-based diets have a direct effect on the prevalence of the disease (Vioque, Torres and Quiles, Reference Vioque, Torres and Quiles2000; WHO, 2003; Forouzanfar et al., Reference Forouzanfar2013; León- Muñoz et al., Reference León-Muñoz, Gutiérrez-Fisac, Guallar-Castillón, Regidor, López-García, Martínez-Gómez, Graciani, Banegas and Rodríguez-Artalejo2014; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2015; Antonio-Anderson, Félix-Verduzco and Gutiérrez-Flores, Reference Antonio-Anderson, Félix-Verduzco and Gutiérrez Flores2020). Smoking cessation leads to weight gain as does habitual alcohol consumption (Flegal et al., Reference Flegal, Troiano, Pamuk, Kuczmarski and Campbell1995, Cea Calvo et al., Reference Cea-Calvo, Moreno, Monereo, Gil-Guillén, Lozano, Martí-Canales, Llisterri, Aznar, González-Esteba and Redón2008; Dare et al., Reference Dare, Mackay and Pell2015; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Bouna-Pyrrou et al., Reference Bouna-Pyrrou, Muehle, Kornhuber, Weinland and Lenz2021; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Lee2021; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Mkhonta and Sibeko2022; Restrepo, Reference Restrepo2022).

Regarding the importance of social factors such as family size, family structure, number of people living in the same household, hygiene and parental neglect (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Power, Logan and Summerbelt1999), show that the probability of being overweight in cases of not living alone is higher (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Antelo et al., Reference Antelo, Magdalena and Reboredo2017; Mohammad-Nasrabadi et al., Reference Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, Sadeghi, Rahimiforushani, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, Shojawizadeh and Montazeri2019).

Other consequences of being overweight include being subjected to singling out or discrimination for not conforming to an idealized physical appearance, which has psychological repercussions (Tamayo and Restrepo, Reference Tamayo Lopera and Restrepo2014; De Domingo and López, Reference De Domingo Bartolomé and López Guzmán2014), hindering full integration into society and even access to jobs (Massicard et al. (Reference Massicard, Alsibai, Nacher and Sabbah2022).

When the individual problems derived from overweight/obesity are generalized in aggregate in the economy of a country, mainly due to the resources that must be allocated to medical care and related diseases, it leads to consider it as a public health problem. (Rtveladze et al., Reference Rtveladze, Marsh, Barquera, Romero, Levy, Melendez, Webber, Klipi, McPherson and Brown2014; IMCO, 2015; Molina et al., Reference Molina, Pérez, Alonso, Martínez, Castellanos, del Valle Laisequilla and Alonso2015; Sassi et al., Reference Sassi, Devaux, Cecchini and Scheffler2016). Obesity in the population reduces the life expectancy of countries, but also has a strong negative economic impact on their health budgets, as it is also a triggering factor for a number of long-term diseases and high care costs, commonly known as chronic degenerative diseases. In fact, obesity substantially increases not only the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease but also of certain types of cancer and other highly prevalent diseases (Must et al., Reference Must, Spadano, Coakley, Field, Colditz and Dietz1999; Mokdad et al., Reference Mokdad, Ford, Bowman, Dietz, Vinicor, Bales and Marks2003; Calle et al., Reference Calle, Rodriguez, Walker-Thurmond and Thun2003). For all these reasons, it is necessary to analyse the economic impact of obesity care and its consequences both for individuals and for public health services. For many countries, the direct and indirect costs of obesity care are enormous. On the one hand, obesity, like other chronic degenerative diseases, generates high care costs for patients and their families during long periods of treatment, and on the other hand, at the level of public and private health institutions, the medical care of these patients is costly and long term, since it involves frequent medical appointments and various medical examinations to evaluate the evolution of the problem, as well as its associated diseases. A review of the literature on the economic impact of obesity indicates that the direct costs of the disease in various first world countries represent between 2 and 7% of their public health budget (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Chou, Chou, Lee, Lee and Huang2008; Kouris-Blazos, & Wahlqvist, Reference Kouris-Blazos and Wahlqvist2007; Witkos et al., Reference Witkos, Uttaburanont, Lang and Arora2008; Anis et al., Reference Anis, Zhang, Bansback, Guh, Amarsi and Birmingham2010).

Overweight/obesity has, therefore, numerous fundamental determinants beyond genetics and involves numerous socioeconomic factors; thus, the aim of this work is also to determine the importance that these socioeconomic factors have on overweight by using logistic models on a microdata base constructed from surveys conducted between July 2019 and July 2020 to a representative sample of the entire Spanish population aged 15 years or older, as well as each of the regions (Autonomous Communities) that make up this country, including Andalusia. In addition to variables commonly used by the literature in this type of studies, other novel variables such as marital status, living in urban or rural areas, habits, and lifestyle of individuals, oral health, among others, have been included. These variables are less explored and must be considered in health policies to combat this disease, and their inclusion, in our opinion, makes the model more robust.

Methods

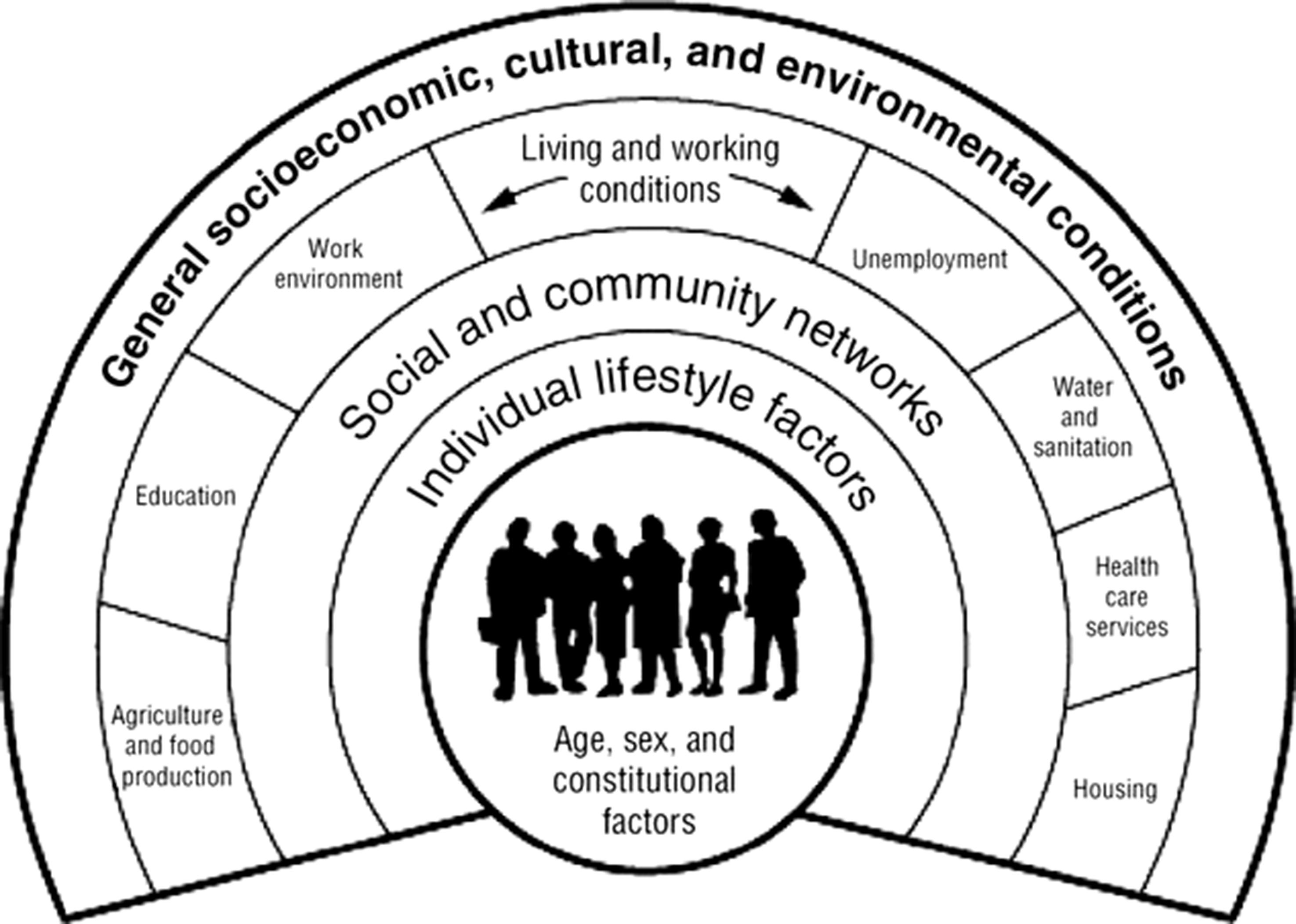

This study adapts the classic model of Dalghren and Whitehead (Reference Dalghren and Whitehead1991) for an analysis of the Spanish and Andalusian cases. The model of these two economists has been widely used and shows the determinants of health in concentric layers, from structural determinants (external layer) to individual lifestyles (internal layer), placing at the centre the characteristics of individuals that cannot be modified, such as sex, age, or constitutional factors (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The Dalghren-Whitehead model of determinants in health.

Source: Dalghren and Whitehead (Reference Dalghren and Whitehead1991).

To achieve the objective proposed in this paper, the European Survey of Health in Spain (ESHS-2020) is used. This constitutes a microdata base constructed from interviews conducted between July 2019 and July 2020 with a representative sample of the population aged 15 years and older in Spain as a whole, as well as in each of its regions (including Andalusia). The ESHS-2020 contains a total of 22,072 valid observations (2,820 of them belonging to the Andalusian population).

Given that the ESHS-2020 is constructed through surveys conducted at a specific point in time, it consists of a cross-sectional database. Likewise, the fact that it is constructed through surveys implies that most of its component variables are qualitative, including the one that acts as the dependent variable in our estimations (which is defined in Table 1). All these characteristics condition the estimator to be used.

Table 1. Variables used in the analysis and their definition

So much so that for this reason we estimate qualitative response models. Specifically, we resort to logit estimations and, more precisely, to the odds ratios (hereinafter, OR in singular and ORs in plural) that result from them. The latter provide a great deal of information and are easy to interpret. Thus, an OR greater than 1 indicates that the explanatory variable is positively associated with the dependent variable. The higher the OR is greater than 1, the stronger the positive association. If the OR is less than 1, then the explanatory variable is negatively associated with the dependent variable. The closer the OR is to 0, the greater the strength of the negative association. ORs equal to 1 denote the absence of a relationship between the explanatory variable and the dependent variable. Be that as it may, the estimation of this type of model is not uncommon in this field of research (Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Tavares, Ferreira, Welch, Horta, Cardoso and Santos2021; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Lee2021, to name a few).

But in addition to the ORs (which indicate that ‘the odds of the event occurring in an exposed group versus the odds of the event occurring in a non-exposed group’ – Tenny and Hoffman, Reference Tenny and Hoffman2023), we consider the Average Marginal Effects (hereinafter, AMEs in plural and AME in singular). The latter expresses the average effect of the explanatory variable on the probability that the contrast category of the dependent variable (y=1; in this case, BMI≥25) occurs (Mood, Reference Mood2010, Reference Mood2017). Regarding its interpretation, considering that the AME corresponding to the gender variable was −0.17 (being the dependent variable to be overweight) that would mean that women have 17% points lower probability of being overweight compared to men. If that value were 0.17 (positive) then women would be 17% points more probably to be overweight than men.

Altogether, we estimate six logistic models: three for Spain as a whole and another three for Andalusia. The reasons why we do this are detailed later in this same section (specifically, when dealing with multicollinearity analysis). Table 1 includes the variables used in the estimations, as well as their definition. Table 2 contains the statistical descriptive summary of these variables. STATA 15.1. is the software used both for this summary and for the rest of the analyses performed in this paper.

Table 2. Statistical-descriptive summary of the variables used

The remainder of this section deals with the specifications of the estimated models, as well as the pre- and post-estimation analysis that must be carried out to guarantee the reliability, validity, and robustness of the results obtained (and, therefore, of the conclusions drawn from them). In this way, it will be possible to resolve the objective proposed in this paper, placing special emphasis on the testing of the following three hypotheses:

H1: Those who have attained tertiary education are less likely to exceed their normal weight (i.e., to incur a BMI≥25) than those whose maximum educational attainment is not tertiary.

H2: Residing in a household whose net monthly income exceeds the average net monthly income of Spanish (or, as the case may be, Andalusian) households decreases the probability of having a BMI≥25 (i.e., of being overweight).

H3: Having attained tertiary education is more effective in the fight against overweight than residing in a household whose net monthly income exceeds the average net monthly income of Spain (or Andalusia, as the case may be), both factors being effective in the aforementioned fight. In this sense, we would be assuming that the social gradient of overweight is more pronounced with respect to educational attainment than with respect to income.

Beginning with the pre-estimation analysis, the fact that the individuals that make up the sample of the microdata base we use were randomly selected guarantees the randomness assumption. However, we cannot confirm the assumption of normality of the random disturbances because they are binary (as are the dependent variables) and, therefore, follow the Bernoulli distribution. This is not a problem when estimating binary qualitative response models. In fact, even in the context of the classical linear regression model, ‘if the objective is point estimation, the assumption of normality is not necessary’ (Gujarati and Porter, Reference Gujarati and Porter2009, p. 544).

Likewise, given that the microdata base we use is cross-sectional, the presence of autocorrelation is highly improbable, especially if the data have been collected randomly (as is the case). We also do not address the presence of outliers since these are only a problem when they are due to human error (Draper and Smith, Reference Draper and Smith1998, p. 76), which we are not aware of. Similarly, when we are estimating binary qualitative response models using the maximum likelihood method (as we do here) we should not be concerned with the potential problem of heteroscedasticity (Ginker and Lieberman, Reference Ginker and Lieberman2017).

However, it is important that there is not a high degree of correlation between two or more explanatory variables of the model to be estimated (i.e., that there is no multicollinearity). To detect this, we use the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). By virtue of VIFs’ values, we can know how the variance of an estimator is inflated due to the presence of collinearity. Table 3 shows VIFs’ values well below 10. According to the related literature, we can conclude that there are no multicollinearity problems in any of our estimations (Gujarati and Porter, Reference Gujarati and Porter2009, p. 340; Greene, Reference Greene2018, p. 95).

Table 3. Multicollinearity analysis through VIFs’ Values

Note that Table 3 contains the VIFs’ values for six estimations (three estimations for each of the territories analysed: Spain as a whole and Andalusia). This is because, although the VIFs’ values of the first estimation denote that there are no multicollinearity problems, we consider that our results will be even more valid, robust, and reliable if we perform alternative estimations to the first one, which ‘isolate’ the main variables of this paper (on the one hand, income, and, on the other hand, basic education and tertiary education). Thus:

-

The first estimated model includes all the variables indicated in Table 1.

-

The second estimated model includes all the same variables as the first model, with the exception of ‘income’.

-

The third estimated model considers all the variables included in the first model, with the exception of both ‘basic education’ and ‘tertiary education’.

Therefore, the results yielded by these variables are expected to be consistent in the three estimations that we run for each of the territories analysed. Altogether, we run six estimations (as previously announced in this section). With respect to the specifications of the estimated models, note the following:

$$\eqalign{Logit\;\left[ {P\left( {Y = 1} \right)} \right] & = F\left( {{\beta _0} + {\beta _1}gen + {\beta _2}nat + {\beta _3}age + {\beta _4}edu + {\beta _5}emp + {\beta _6}inc + {\beta _7}urb}\right. \cr & \ \ \ \ \left.{+\ {\beta _8}hou + {\beta _9}sed + {\beta _{10}}hdi + {\beta _{11}}smk + {\beta _{12}}alc + {\beta _{13}}smd + {\beta _{14}}vac + {\beta _{15}}car}\right. \cr & \ \ \ \ \left.{+ \;{\beta _{16}}pri + \;{\beta _{17}}orh + {\beta _{18}}sub + {\beta _{19}}dep + {u_i}} \right) } $$

$$\eqalign{Logit\;\left[ {P\left( {Y = 1} \right)} \right] & = F\left( {{\beta _0} + {\beta _1}gen + {\beta _2}nat + {\beta _3}age + {\beta _4}edu + {\beta _5}emp + {\beta _6}inc + {\beta _7}urb}\right. \cr & \ \ \ \ \left.{+\ {\beta _8}hou + {\beta _9}sed + {\beta _{10}}hdi + {\beta _{11}}smk + {\beta _{12}}alc + {\beta _{13}}smd + {\beta _{14}}vac + {\beta _{15}}car}\right. \cr & \ \ \ \ \left.{+ \;{\beta _{16}}pri + \;{\beta _{17}}orh + {\beta _{18}}sub + {\beta _{19}}dep + {u_i}} \right) } $$

where

-

$P\left( {Y = 1} \right)$

is the probability that the dependent variable takes the value 1. That is, the probability that the respondent records a BMI ≥ 25.

$P\left( {Y = 1} \right)$

is the probability that the dependent variable takes the value 1. That is, the probability that the respondent records a BMI ≥ 25. -

$F$

: cumulative logistic distribution function.

$F$

: cumulative logistic distribution function. -

$gen{:}$

gender.

$gen{:}$

gender. -

$nat$

: native.

$nat$

: native. -

$age$

: age2, age3, age4, age5, age6, age7, age8.

$age$

: age2, age3, age4, age5, age6, age7, age8. -

$edu$

: educational attainment (basic education, tertiary education).

$edu$

: educational attainment (basic education, tertiary education). -

$emp$

: employment status (unemployed, retired, salaried employee, self-employed).

$emp$

: employment status (unemployed, retired, salaried employee, self-employed). -

$inc$

: income.

$inc$

: income. -

$urb$

: urban.

$urb$

: urban. -

$hou$

: one-person-household.

$hou$

: one-person-household. -

$sed$

: sedentary.

$sed$

: sedentary. -

$hdi$

: health diet.

$hdi$

: health diet. -

$smk$

: smoker.

$smk$

: smoker. -

$alc$

: alcohol.

$alc$

: alcohol. -

$smd$

: self-medicate.

$smd$

: self-medicate. -

$vac$

: vaccinated.

$vac$

: vaccinated. -

$car$

: care.

$car$

: care. -

$pri$

: private insurance.

$pri$

: private insurance. -

$orh$

: oral health.

$orh$

: oral health. -

$sub$

: subjective health status.

$sub$

: subjective health status. -

$dep$

: depressive.

$dep$

: depressive. -

${u_i}$

: random disturbances.

${u_i}$

: random disturbances.

Meanwhile, AMEs are given by (Mood, Reference Mood2010, p. 75):

where

-

$\beta {x_1}$

: estimated LnOR for variable

$\beta {x_1}$

: estimated LnOR for variable

${x_1}$

.

${x_1}$

. -

$\beta {x_i}$

: logit value for the i-th observation.

$\beta {x_i}$

: logit value for the i-th observation. -

$f\left( {\beta {x_i}} \right)$

: logistic probability distribution function with regard to

$f\left( {\beta {x_i}} \right)$

: logistic probability distribution function with regard to

$\beta {x_i}$

.

$\beta {x_i}$

.

Regarding post-estimation analyses, when estimating binary qualitative response models, they are usually focused on verifying the goodness-of-fit. Thus, in all our estimations the count R2 is higher than 0.5, which indicates that there is a correct fit of the data to the models (Camarero-Rioja et al., Reference Camarero Rioja, Almazán Lorente and Mañas Ramírez2013). Moreover, ROC curves’ areas are widely higher than 0.5 in all our estimations, which further supports such goodness-of-fit (Swets, Reference Swets1988). Furthermore, the p-values yielded by Pearson’s test do not allow us to reject the null hypothesis that there is conformity in the predicted and observed frequencies across the patterns. This latter test is complemented by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (which has the same null hypothesis).

Therefore, more evidence supports the goodness-of-fit of the data to the models than indicates the opposite. Even so, when binary qualitative response models are being estimated, although goodness-of-fit is analysed, it ‘is of secondary importance. What matters is the expected signs of the regression coefficients and their statistical and/or practical significance’ (Gujarati and Porter, Reference Gujarati and Porter2009, p. 563).

Results

Table 4 (at the end of this section) provides the empirical results. It also contains information on the tests that guarantee their reliability, validity, and robustness. Note that outside the parentheses are the values of the ORs. Meanwhile, inside the parentheses are the values of the AMEs. The latter have the same level of significance as their corresponding ORs.

Table 4. Empirical results (dependent variable: BMI≥25)

*** p < 0.01

** p < 0.05

* p < 0.10.

Beginning with those factors on which this paper places the greatest emphasis (educational attainment and income), we find that people whose highest level of education attained is secondary school (ISCED 2 or lower) are more likely to be overweight compared to those whose highest level of education is post-secondary (ISCED 3 and 4). Specifically, the odds of yielding a BMI≥25 are 1.3 times higher in Spain (1.2 in Andalusia) for the former compared to the latter (i.e., 5.2–5.6% points higher probability in Spain – and 4.4–4.5 in Andalusia – in view of the AMEs). But, in addition, we find that the probability of having a BMI≥25 is lower when having tertiary education (ISCED 5 or higher). In particular, Spaniards (Andalusians) with tertiary education are between 7.6 and 8.1 (5.5 and 5.6) percentage points less likely to exceed their normal weight compared to the base category (ISCED 3 and 4). In other words, the odds of not becoming overweight are around 1.4 (

![]() $ \approx $

1/0.705

$ \approx $

1/0.705

![]() $ \approx $

1/0.694) times higher in Spain (1/0.768

$ \approx $

1/0.694) times higher in Spain (1/0.768

![]() $ \approx $

1/0.771

$ \approx $

1/0.771

![]() $ \approx $

1.3 in Andalusia) for those with tertiary education compared to those without.

$ \approx $

1.3 in Andalusia) for those with tertiary education compared to those without.

Therefore, higher educational attainment implies a lower risk of overweight both in Andalusia and in Spain as a whole. Meanwhile, our results indicate that those Spaniards who reside in households whose net monthly income exceeds the average monthly net household income for Spain as a whole (2,192.14 euros at the time of the survey) are less likely to be overweight. Precisely, the odds of not becoming overweight are between 1.1 and 1.2 times higher for these individuals (who exceed this average) compared to their counterparts. Moreover, the AMEs indicate that the probabilities of achieving a BMI≥25 are between 2 and 5% points lower for those residing in households whose net monthly income exceeds the national average. We cannot make analogous statements for Andalusia due to lack of significance. Be that as it may, in view of the results, both higher-than-average income levels and higher educational levels decrease the probability of becoming overweight (which confirms hypotheses H1 and H2). Besides, in view of these results, the negative association between income and overweight is less strong than the negative relationship between educational attainment and overweight (which corroborates hypothesis H3).

Likewise, the implications of higher income in the fight against overweight are only found for Spain as a whole, while the role of educational attainment in this fight is found both for Spain as a whole and for Andalusia. It should be noted, however, that the results obtained for both the educational variables (‘basic education’ and ‘tertiary education’) and the ‘income’ variable are consistent in all the estimations where these variables are included. In other words, no conflicting results are found depending on the estimated model, which further reinforces the robustness, reliability, and validity of these results (and, therefore, of the conclusions drawn from them).

Continuing with the results obtained for the rest of the control variables, gender is negatively associated with overweight. Thus, the odds of not being overweight are 2.1 times higher in Spain (2.3 in Andalusia) for women than for men. Also, we find that age is positively related to a BMI≥25. But this relationship is not linear since, for the two populations analysed, the ‘age 5’ group (56–65 years old) registers higher odd ratios than the rest of the groups. In other words, those close to retirement are more likely to be overweight compared to the other groups (4.3–4.4 times higher odds in Spain and 7.4 times higher odds in Andalusia). In any case, belonging to any age group other than the youngest (base category) implies a greater probability of being overweight.

In addition, the odds of not being overweight are around 1.2 times higher for single Spaniards compared to those with another marital status. However, we cannot confirm any relationship between marital status and overweight in Andalusia due to lack of significance. Likewise, the probability of having a BMI≥25 is lower for those who habitually live alone at home (one-person-household) compared to those who share a home with other people (family members, partners, friends, etc.), only in Spain as a whole (around 5% points lower probability). Regarding employment status, the results suggest that the odds of being overweight are, in Spain as a whole, 1.1 times higher among those who are unemployed compared to those who are in another employment situation (2.6–2.7% points higher probability). Meanwhile, in Andalusia, those who are self-employed are around 1.5 times higher odds to score a BMI≥25 compared to those in other employment categories (around 8% points higher probability).

Aside from that, the odds of not having a BMI≥25 are around 1.1 times higher for those individuals residing in provincial capitals (proxy for urban areas) compared to those residing in rural areas. This positive relationship between being rural and being overweight is significant for Spain as a whole, but not for Andalusia. Similarly, the positive relationship between daily alcohol consumption and overweight is not significant for Andalusia but is significant for Spain as a whole. Even so, this relationship is weak (since OR≈1). On the contrary, our results reveal that those who are daily smokers are less likely to be overweight compared to their opposites both in Andalusia and in Spain as a whole. Specifically, the odds of not being overweight are around 1.5 (Spain) and 1.8 (Andalusia) times higher for daily smokers compared to non-smokers.

Additionally, a sedentary lifestyle is positively and significantly associated with overweight. Indeed, sedentary individuals have around 1.3 times higher odds of being overweight compared to their counterparts (both in Andalusia and in Spain as a whole). Moreover, in Andalusia, healthy eaters have 1.4 times lower odds of exceeding their normal weight (i.e., about 7% points lower probability) compared to non-healthy eaters, with no significant results found for this variable in Spain as a whole.

With respect to mental health, our results for Spain as a whole indicate that the odds of not being overweight are around 1.1 times higher among those with depressive symptoms compared to their counterparts (i.e., negative relationship between depression and overweight). As for subjective health status, we find that the worse the individual believes his or her health status to be the higher the probability that he or she has a BMI≥25. Likewise, having poor oral health has an impact on greater overweight, although very weakly (and only significantly in Spain as a whole: 1.1 times more likely). Something similar occurs with respect to being Spanish by birth, which is negatively related to overweight only in Spain as a whole and very weakly (since OR≈1).

Discussion

Given the pandemic importance that overweight has been acquiring in recent years, this paper consists of a renewed version of the study of the determinants of overweight in Spain as a whole, as well as in Andalusia (a region where overweight is palpable). In addition to considering variables typically explored in previous literature such as gender, age, lifestyles, etc. (whose inclusion helps our results to gain in robustness), we address other less explored and even unpublished factors (such as mental health, subjective health status, oral health, urban/rural gaps, etc.), whose consideration contributes to the literature and to which it is hoped that more attention will be paid from now on.

However, in this paper two variables take on special prominence: educational attainment and income. Not so much because of their consideration per se in the empirical analysis, but because the focus is on whether both could be effective in the fight against overweight both in Spain as a whole and in Andalusia, and whether either of these two variables is more effective than the other in this fight. Our findings are consistent with those of previously related literature both regarding the relationship between higher educational attainment and lower risk of overweight (Álvarez-Castaño et al., Reference Álvarez-Castaño, González-Zapata and Góez-Rueda2014; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Rodd and Sharma, Reference Rodd and Sharma2017; Aranceta-Bartrina and Pérez-Rodrigo, Reference Aranceta-Batrina and Pérez-Rodrigo2018; Moreno-Franco et al., Reference Moreno-Franco, Pérez-Tasigchana, Lopez-Garcia, Laclaustra, Gutierrez-Fisac, Rodríguez-Artalejo and Guallar-Castillón2018; Kunzova et al., Reference Kunzova, Maugeri, Medina-Inojosa, López-Jiménez, Vinciguerra and Marques-Vidal2020) as for the negative association between income and overweight (Escolar-Pujolar, Reference Escolar-Pujolar2009; García-Villar and Quintana-Domeque, Reference García-Villar and Quintana-Domeque2009; Martinson et al., Reference Martinson, McLanahan and Brooks-Gunn2012; Álvarez-Castaño et al., Reference Álvarez-Castaño, González-Zapata and Góez-Rueda2014; Arredondo et al., Reference Arredondo, Torres, Orozco, Pacheco, Aragón, Huang and Bolaños-Jiménez2018; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017). The latter association is typical, moreover, in the context of developed economies (such as Spain), as the opposite could be true in economies with lower levels of development (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Conde and Popkin2001; Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Tavares, Ferreira, Welch, Horta, Cardoso and Santos2021; Massicard et al., Reference Massicard, Alsibai, Nacher and Sabbah2022).

But, be that as it may, we cannot ignore that, according to our results, a high educational attainment has more relevant implications in less overweight than income levels above the average (national and regional). In fact, in Andalusia, the income variable does not even show significance. In other words, and in line with Rodríguez-Caro et al. (Reference Rodríguez-Caro, Vallejo-Torres and López-Valcarcel2016), we can confirm that the social gradient of overweight is more pronounced with respect to educational attainment than with respect to income (in both Spain as a whole and Andalusia). This reflection on the social gradient makes sense given that general educational attainment can be considered as a proxy variable for health literacy (Kickbusch, Reference Kickbusch2001). Indeed, health literacy can improve a person’s ability to adequately cope with his/her health problems (including overweight). And, moreover, such education (or literacy) can do so from a broader spectrum than having ample purchasing power to buy goods and services that allow that individual with higher income to lead a more favourable lifestyle in terms of his or her weight status (Costa-Font and Gil, Reference Costa-Font and Gil2008; Merino-Ventosa and Urbanos-Garrido, Reference Merino-Ventosa and Urbanos-Garrido2016, Antelo et al., Reference Antelo, Magdalena and Reboredo2017).

So much so that Mosli et al. (Reference Mosli, Kutbi, Alhasan and Mosli2020), after stratifying individuals according to their income level, showed that higher educational attainment is related to lower overweight in all income strata (and that this relationship was even stronger in the upper-income stratum). Somehow, and in line with the OECD (Devoux et al., Reference Devoux, Sassi, Church, Cecchini and Borgonovi2011, p. 140), this broader spectrum of education with respect to income could be manifested by (i) greater access to health-related information and a better ability to manage it; (ii) a clearer perception of the risks associated with each lifestyle; and (iii) greater long-term self-control in health preferences. Some even argue that greater educational attainment can lead individuals to move out of obesogenic social environments toward healthier ones, in general, and more inclined toward a normal weight, in particular (Harrington and Elliot, Reference Harrington and Elliot2009). It would also have been interesting to be able to analyse to what extent the long-term implications of educational attainment on income level could influence a lower risk of BMI≥25. But unfortunately, that is not possible since we do not use longitudinal data, but rather cross-sectional data (common when surveys are used).

Nevertheless, there are authors who argue that overweight/obesity could be a social stigma and thus a reason for discrimination and that this could be an obstacle to both schooling and earning an income (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Roesler and von dem Knesebeck2017; Kim and von dem Knesebeck, Reference Kim and von dem Knesebeck2018). In other words, no longer only low income and low educational attainment could lead to a higher risk of overweight/obesity, but, in turn, higher overweight/obesity could lead to lower income and lower educational attainment. If this were the case, we would be facing a reverse causality scenario with the endogeneity problems that this would entail. For this reason, we have applied the Durbin-Wu-Hausman test (DWH test) to the educational and income variables.

DWH test consists of an endogeneity test whose null hypothesis holds that the explanatory variables analysed are exogenous (Gujarati and Porter, Reference Gujarati and Porter2009, p. 703; Greene, Reference Greene2018, p. 276; Davidson and Mackinnon, Reference Davidson and MacKinnon2021, p. 237). P-values obtained when applying this test with both the income variable and the educational variables are greater than 0.05.Footnote 3 Thus, there is not enough statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis, and, therefore, it must be retained. In other words, we can assume that the explanatory variables are exogenous (and that, therefore, there are no endogeneity problems because of this). This, in turn, completes the multicollinearity analysis outlined in ‘Methods’.

Regarding our findings about gender, previous papers have already pointed out this negative association between being female and being overweight in the context of developed economies, such as European or Spanish economies (e.g., Antelo et al., Reference Antelo, Magdalena and Reboredo2017; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Rodd and Sharma, Reference Rodd and Sharma2017; Aranceta-Bartrina and Pérez-Rodrigo, Reference Aranceta-Batrina and Pérez-Rodrigo2018; Kunzova et al., Reference Kunzova, Maugeri, Medina-Inojosa, López-Jiménez, Vinciguerra and Marques-Vidal2020). While it is true that in economies with a lower level of development, the opposite relationship usually occurs (Álvarez-Castaño et al., Reference Álvarez-Castaño, González-Zapata and Góez-Rueda2014; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Emamian et al., Reference Emamian, Fateh, Hosseinpoor, Alami and Fotouhi2017). In a way, this hints that in those countries where women’s rights are more consolidated (and their role is not only limited to the sphere of both domestic and family chores) women are more concerned about having a healthy weight compared to their counterparts in countries less developed in that regard (Luglio et al., Reference Luglio, Nisa, Penggalih, Helmyati, Arsanti, Utami, Putri, Tirta, Susetyowati, Huriyati and Sudargo2017). Even this non-exclusivity to that sphere can lead them to postpone certain goals such as pregnancy, with the implications that Wells et al. (Reference Wells, Marphatia, Manandhar, Cortina-Borja, Reid and Saville2022) have shown that this can have on the good nutritional status of women.

On marital status, our findings are consistent with previous papers (Merino-Ventosa and Urbanos-Garrido, Reference Merino-Ventosa and Urbanos-Garrido2016; Emamian et al., Reference Emamian, Fateh, Hosseinpoor, Alami and Fotouhi2017; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Mohammad-Nasrabadi et al., Reference Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, Sadeghi, Rahimiforushani, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, Shojawizadeh and Montazeri2019). Perhaps, this relationship lies in the need for singles to take care of their physical appearance in order to be able to find a serious partner in the future. This reasoning is consistent with those works that have evidenced the relationship between overweight and casual sexual encounters to the detriment of serious romantic relationships (more common among those with normal weight) that end up leading to a change in the marital status of individuals (Frederick and Jenkins, Reference Frederick and Jenkins2015; Granberg et al., Reference Granberg, Simons and Simons2015). Besides, our findings on the implications that residing in urban areas has on BMI≥25 contribute to reduce the controversy about the direction of urban-rural gaps in overweight (Sjoberg et al., Reference Sjoberg, Moraeus, Lissner, Poortvliet, Al-Ansari and Yngve2012; Emamian et al., Reference Emamian, Fateh, Hosseinpoor, Alami and Fotouhi2017; Rood y Sharma, Reference Rodd and Sharma2017; Thapa et al., Reference Thapa, Dahl, Aung and Bjertness2021). That positive relationship between being rural and being overweight is probably due to the greater peace of mind in rural areas compared to urban areas. We also complete the previous literature on the relationship between household size and overweight (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Antelo et al., Reference Antelo, Magdalena and Reboredo2017; Mohammad-Nasrabadi et al., Reference Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, Sadeghi, Rahimiforushani, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, Shojawizadeh and Montazeri2019).

Previous publications support our findings on the nonlinear relationship between age and BMI≥25 (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Aranceta-Bartrina and Pérez-Rodrigo, Reference Aranceta-Batrina and Pérez-Rodrigo2018; Kunzova et al., Reference Kunzova, Maugeri, Medina-Inojosa, López-Jiménez, Vinciguerra and Marques-Vidal2020; Coimbra et al., Reference Coimbra, Tavares, Ferreira, Welch, Horta, Cardoso and Santos2021). In this sense, other authors have already suggested that the fact that adolescents and, in general, young people are more concerned about their physique than older people could influence their lower prevalence of being overweight (Júlíusson et al., Reference Júlíusson, Eide, Roelants, Waaler, Hauspie and Bjerknes2010; Antelo et al., Reference Antelo, Magdalena and Reboredo2017). All in all, it should not be overlooked that weight gain and body fat accumulation is a biological process that is not unrelated to ageing and the metabolic changes that ageing entails (Vlassopoulos et al., Reference Vlassopoulos, Combet and Lean2014), which is also consistent with what our empirical results suggest.

Regarding employment status, for Spain as a whole, we find a positive and significant relationship between being unemployed and being overweight, in line with Massicard et al. (Reference Massicard, Alsibai, Nacher and Sabbah2022). In this sense, Watson et al. (Reference Watson, Daley, Rohde and Osberg2020) pointed to economic stress caused by job insecurity and increased unemployment as one of the causes of the increase in BMI of the Canadian population during the great recession. Likewise, our findings on the effects of being self-employed in Andalusia on overweight are consistent with previous literature (Nemoto et al., Reference Nemoto, Sakurai, Matsunaga, Hasebe and Fujiwara2022). The lack of significance for the other employment statuses prevents us from confirming that the employed population are more likely than the inactive to be overweight, perhaps due to their different lifestyles, as Ohta et al. (Reference Ohta, Takeuchi, Yosiaki and Suzuki1998) noted. About lifestyles, our findings regarding alcohol and tobacco consumption are consistent with those of previous literature (Dare et al., Reference Dare, Mackay and Pell2015; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Bouna-Pyrrou et al., Reference Bouna-Pyrrou, Muehle, Kornhuber, Weinland and Lenz2021; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Lee2021; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Mkhonta and Sibeko2022; Restrepo, Reference Restrepo2022). Also not surprising is the relationship we find between eating healthy and overweight (Mandal and Powell, Reference Mandal and Powell2014; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wu, Zhao, Ma, Shi and Zhou2021; Dédelè et al., Reference Dèdelé, Bartkuté, Chebotarova and Miškinyté2021).

We also agree with other authors (Lakdawalla and Philipson, Reference Lakdawalla and Philipson2002; Merino-Ventosa and Urbanos-Garrido, Reference Merino-Ventosa and Urbanos-Garrido2016; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Lee2021; Pacific et al., Reference Pacific, Kulwa, Martin and Petrucka2022) in finding that a sedentary lifestyle is positively and significantly associated with overweight. Similarly, we reinforce previous literature around the implications of being native-born Spaniard (and thus non-immigrant and non-racial/ethnic minority) on overweight (Martinson et al., Reference Martinson, McLanahan and Brooks-Gunn2012; Raftopoulou, Reference Raftopoulou2017; Rodd and Sharman, Reference Rodd and Sharma2017).

With our findings on the relationship between depression and overweight, we contribute to reduce the controversy that still surrounds this issue. On the one hand, we move closer to Pérez-Cruz et al. (Reference Pérez-Cruz, Lizárraga-Sánchez and Martínez-Esteves2014), who relate depression to appetite and weight loss. On the other hand, we move away from those authors who claim that people with depression tend to gain weight because they ‘satiate’ their emotional problems by eating (Tannenbaum et al., Reference Tannenbaum, Anisman, Abizaid, Dubé, Bechara and Dagher2010; Gearhardt et al., Reference Gearhardt, Harrison and McKee2012). It would have been interesting if the ESHS-2020 had provided information on the different types of depression that exist in order to analyse how each of these types could influence weight gain or loss, in line with Alves-Silva et al. (Reference Alves-Silva, da-Silva-Freire-Countinho, Onofre-Ferriani and Viana2020) and Villagrasa-Blasco et al. (Reference Villagrasa-Blasco, García-Jiménez, Bodoano and Gutiérrez-Rojas2020).

Ending this section, our results on the association between poor oral health and overweight are consistent with those of previous research pointing out that those who have fewer teeth and/or it hurts when chewing tend to eat softer foods (which are usually richer in sugars and fats) and, consequently, put on weight (Sonoda et al., Reference Sonoda, Fukuda, Kitamura, Hayashida, Kawashita, Furugen, Koyama and Saito2018; Tôrres et al., Reference Tôrres, Da Silva, Neri, Hilgert, Hugo and Sousa2013, Reference Tôrres, De Marchi, Hilgert, Hugo, Ismail, Antunes and Sousa2020). Analogously, some previous papers have pointed out that the subjective perception of individuals’ own health status may lead them to underestimate their weight, to the extent that such underestimation results in them being unconcerned about their actual weight status and recording BMI≥25 (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Blanck, Gillespie, Maynard and Serdula2008; Peltzer and Pengpid, Reference Peltzer and Pengpid2015). Precisely, our findings are along these lines.

Conclusions

Obesity is considered the great pandemic of the 21st century and is increasing the health costs borne by countries. However, what is more important in the fight against overweight, income per se, or the level of education attained? What other socioeconomic factors and habits lead to lower overweight? We have tried to answer these and other questions in this paper. Using the ESHS-2020, logistic models have been developed with more than 22,000 observations for the Spanish case, of which almost 3,000 correspond to respondents from Andalusia.

Regarding the two main variables of this paper (educational attainment and income), the implications of our findings are not very different in Andalusia compared to Spain as a whole. In this sense, we conclude that, in both cases, high educational attainment is more effective in the fight against overweight than high purchasing power (income). In other words, the social gradient of overweight is more pronounced with respect to educational attainment than with respect to income both in Andalusia and in Spain as a whole. This suggests that, in some way, those who are better educated are better able to access, understand, and use health-related information in a more appropriate way than their counterparts. This should ultimately result in a better weight status. Therefore, if lower rates of overweight are to be achieved (which would imply lower healthcare costs, both public and private) policymakers should promote more universal access to public tertiary education (which in Spain, and specifically in Andalusia, is offered at very low prices, but is still not free – as lower levels of education are).

In addition to the avoidance of obesogenic both habits and environments that can lead to greater educational attainment, it is important, in view of our findings, not to neglect the active and specific public promotion of lower alcohol consumption, less sedentary lifestyles, and better oral health. Nor would it be preposterous to promote further research into those active substances of tobacco that reduce overweight (if any) and that (in this case) could be offered as a treatment, but avoiding the well-known pernicious effects that smoking has on the health of individuals.

We have also shed light on other aspects less explored in previous related literature (such as subjective health status, urban-rural gaps, among others) on which we expect to see more future research from now on. Nor have we neglected other factors more typically explored in that literature (such as marital status, household structure, urban/rural gaps, gender, and age, among others), without ignoring the biological aspects intrinsic to some of them (especially the last two). Nevertheless, our contribution is not free of limitations which, to a large extent, can be explained by the microdata base we use. Thus, given that it is based on surveys carried out at a specific moment in time, longitudinal analysis is not feasible. Consequently, it is also not possible to use panel data estimators, which are usually more efficient than cross-sectional estimators (Baltagi, Reference Baltagi2005, p. 5; Gujarati and Porter, Reference Gujarati and Porter2009, p. 592).

Another limitation has to do with how some variables are defined. The most notorious case is that of the income variable. Indeed, the database used does not offer a continuous version of this variable, but rather an ordinal polytomous variable of income defined by different ranges (see Table 1 in the ‘methods’ section of this paper). Therefore, we do not know the exact (and not even approximate) amount, in euros, of individuals’ income. Moreover, we only know the net monthly income of the household in which the respondent resides (and not even his/her own). Moreover, if the value of this income is 1,660 euros for one individual and 2,250 euros for another, both would be within the same income range. All this leads us to consider income as a binary variable that acquires the value 1 when the net monthly income of the household in which the individual resides exceeds the average net monthly income of Spanish (or Andalusian, as the case may be) households, in the terms established in the aforementioned Table 1. This type of circumstance further accentuates the presence of dichotomous variables, which are already common in microdata bases.

Indeed, the limited presence of quantitative variables makes it difficult to create variables that allow us to go beyond what this microdata base offers (which we consider to be an additional limitation). Thus, for example, having a quantitative variable of income would have allowed us to create variables of economic inequality and analyse its relationship with external and macroeconomic variables. Incidentally, it would have contributed to the longitudinal perspective and the use of panel data estimators mentioned above. As a final limitation, we note the lack of information on COVID-19, which is understandable given that the outbreak of this pandemic occurred in the middle of the survey period. We hope that future editions of the ESHS, in addition to including such information, will provide more precise variables on the income of individuals and their households.

Data availability statement

The European Health Interview Survey microdata in Spain are available electronically on the Statistics National Institute of Spain (www.ine.es).

Acknowledgements

The authors Almudena Guarnido-Rueda and Ignacio Amate-Fortes are grateful for all the suggestions received during the research stay at the Economics Department of UC Santa Barbara.

Funding statement

This study was funded by the European Union, Junta de Andalucía, and University of Almeria, with reference numbers UAL-FEDER 2020, UAL2020-SEJ-D1999.

Competing interests

There is no financial interest or benefits.

Ethical standard

Ethical approval was not required for this study because it is based on data published by official agencies.