In The Double Crisis of the Welfare State (2012) and other work (2016), I argue that in the case of the UK, policies since 2010 have done little to address the long-term problem of competitiveness. Instead they have compounded it by curtailing social policy resources, directing what was available to pensions and to some extent health care (with real cuts in social care) financed mainly by harsh cuts on working-age people. These have won votes but limited capacity for serious social investment and harmed those whose interests have already been damaged by social change. These trends have deepened social divisions and are an important factor in the Brexit referendum outcome.

This article examines recent developments in relation to the double crisis, considers the social divisions that current short-term policies in the context of structural challenges generate, and looks at their contribution to political mistrust and to the Brexit vote. It also discusses the likely impact of Brexit on state welfare in the UK and on those who feel left behind by globalisation. It goes on to discuss the impact of divisive policies on the continuing trajectory of the double crisis.

The continuing double crisis: long and short-term pressures

Long-term structural challenges: globalisation and population ageing

The double crisis identified two major long-term pressures on the UK welfare state: globalisation and technological change, and population ageing. These processes are very different in their impact on the welfare state and on welfare politics. Globalisation and technological changes expose the UK economy to much wider and more competitive markets in an expanding range of goods and services, and require continual improvements in productivity to justify living standards which are relatively high in international comparisons. This in turn requires infrastructure investment, research and development spending and (of particular relevance to welfare state policies) skill training and education to improve the quality and workforce mobilisation to increase the quantity of workers. Both economic openness and the policies listed above are endorsed by the EU in the Europe 2020 strategy (EC, 2017).

This strategy affects welfare state policy in the areas of education, training and life-time learning, includes programmes to move groups currently not in employment into paid work, and provides support for particular groups, notably in family-friendly employment and child-care provision. However, a productivity-enhancing response to globalisation can damage support for this strategy and for the EU among some groups. Those with high-demand skills who are located in favoured areas find that globalisation creates opportunities. They can be seen as winners. Conversely those with obsolete skills or who are less mobile will tend to lose out (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Hoglinger, Hutter and Wuest2012; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2013). The impact of globalisation reinforces that of technological changes which lead to the deskilling of many jobs and the expansion of the service sector at the expense of manufacturing, with a growing division between high-end, high-skill jobs and lower-skilled less-secure employment. The decline of the capacity of workers to resist these changes, associated with the decline of trade unions, also plays a role.

These processes lead to the dualisation of labour markets to a greater or lesser extent in European countries (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012; Rueda, Reference Rueda2007). Arguably the UK has experienced more rapid expansion of the service sector than its neighbours with a more marked division between higher-skilled and lower-skilled jobs within it, so that the range of outcomes is better understood as a ‘fanning out’ of inequalities rather than a dualisation (Felstead et al., Reference Felstead, Gallie and Green2015). The conflict of interest between winners and losers from globalisation and the failure of government policies to mitigate it is a major contributory factor in the divisive politics that has led to Brexit. The EU champions open markets and open borders (European Policy Centre, 2017). Those who feel left behind in a rapidly changing economy demand protectionism not openness. They reject the EU and a political establishment they feel is remote and concerned to promote the interests of the more highly skilled groups who win out from globalisation (Ford and Goodwin, Reference Ford and Goodwin2014).

By contrast, the second aspect of long-term pressures, population ageing, concerns consumption rather than production. Its major effect is to increase the demand for pensions and health and social care, requiring higher levels of funding and reforms to ensure that provision is cost-efficient. Pensions are generally popular and older people are a powerful political force. The coincidence of globalisation/labour market transformation and population ageing poses difficult choices for policy makers, between spending more on younger people to enhance competitiveness or on the growing numbers of older people outside the labour force. Domestic policy has also failed to meet the needs of those disadvantaged by globalisation and industrial change and this reinforced its contribution to support for Brexit.

Since 2010 the Conservative-led coalition and the 2015 Conservative government have retrenched most areas of state spending, but have cut back on health care and pensions spending much less sharply than on local government and on the benefits and services most used by people of working age (Hills, Reference Hills2015; Belfield et al., Reference Belfield, Cribb, Hood and Joyce2016). They have tackled one long-term problem, population ageing, at the expense of exacerbating the other, maintaining competitiveness in a globalised world, and this has further damaged the losers from globalisation, enhancing support for Brexit.

Globalisation, technological change and the labour market

More intense international competition and technological change require, among other things, that governments ensure their industries compete effectively. This depends on a number of factors including production costs, labour costs, skill levels and the availability of workers. Welfare state policies (and the incidence of the taxes to fund them) affect all these areas.

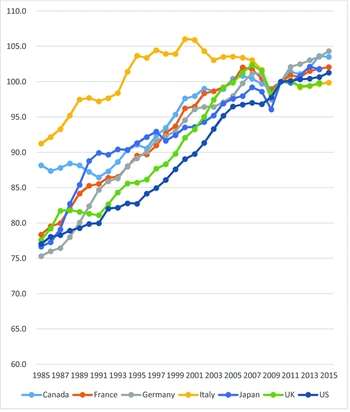

Wages have traditionally been relatively low in the UK. They rose during the early 2000s, compared to other G7 countries, but then fell substantially after 2007 (OECD, 2016a). Unit labour costs, understood as the average cost of labour per unit of output and taking into account such factors as social insurance costs, are also low. However, low taxes and cheap labour cannot ensure a strong international competitive position; it is what is done with the labour that counts as well as what it costs. Multi-factor productivity (taking into account the costs of labour, energy, goods purchased, capital employed and management costs to produce each item of output) has lagged behind other G7 countries, apart from a brief period between 2001 and 2007 (Figure 1). One outcome of the UK's poor performance is a chronic balance of payments deficit.

Figure 1. Multifactor productivity index (2010=100, OECD statistics)

In this situation, one way forward is for government to attempt to stimulate private investment and/or to invest itself. The current government has pursued policies to facilitate investment, cutting taxes on business sharply and income tax less sharply and increasing indirect taxation. Income tax fell from 14 to 12 per cent of government revenues between 2010 and 2016, while the more regressive VAT rose from 14 to 16 per cent (OECD, 2016b). National Insurance contribution revenues remained at about six per cent, while business taxes fell from 2.5 to two per cent and total revenues increased slightly. The net effect has been to shift the burden of paying for deficit reduction more towards lower-income groups (Johnson, Reference Johnson2015: 5).

Farnsworth (Reference Farnsworth2015) estimates the ‘corporate welfare state’ (the subsidies, capital grants, insurance and advocacy as well as transport, energy and procurement subsidies directed at the private sector) at £183bn a year or roughly ten per cent of GDP, rather more than is gathered in tax on business. The low-tax strategy has encouraged business to locate in the UK and, all things being equal, to expand but has had limited success in improving productivity. Businesses have failed to increase investment for each worker, preferring in general to employ more workers at relatively low wages.

The UK has lagged behind all other G7 members except Japan in improvements to capital ‘deepening’ (the rate of change in capital stock per labour hour) for most of the last three decades. It improved its position to midway between 2006 and 2009 but fell back sharply after 2010 (OECD, 2016a) Proposals for a National Investment Bank which would direct money to high-tech projects have been advanced by the Labour opposition (Guardian, 2016) but are unlikely to be taken forward. The Autumn Statement promises £4.7billion over five years to support productivity through R&D, plus small amounts of infrastructure spending (Treasury, 2016). This will raise R&D expenditure in the UK from 1.7 to 1.75 per cent of GDP, much lower than competitors such as Germany (2.9 per cent), France (2.2) or the USA (2.7) (Eurostat, 2016b). The weakness of investment throws the emphasis back on labour market policy – the quantity and quality of workers.

The government has mobilised more groups into work, mainly by making alternatives for unemployed and sick and disabled people less tolerable, increasing minimum wages as incentives and improving labour flexibility by reducing employment rights. Benefit cuts are discussed in more detail below in relation to poverty and inequality. It is unlikely that the April 2016 increase in the National Minimum Wage, renamed the National Living Wage, from 48 to 49 per cent of median wages for full-time workers (OECD, 2016b) will have much effect. The amounts are insufficient to address the scale of the problem and much goes to household members who are not in poverty because their partners earn more (Browne and Hood, Reference Browne and Hood2016: 2).

The period of employment required before protection against dismissal applies was lengthened from one to two years in 2011, fees for industrial tribunals were introduced and rapidly increased from 2013 onwards (cutting recourse to the system by 70 per cent in one year) and rights to preservation of conditions of employment when public sector workers are transferred to the private sector were diluted in 2014. The 2016 Trade Union Act curtails rights to strike and picket, especially for core public sector workers. Such measures are likely to make workers more compliant and all things being equal may improve productivity.

The employment rate of 73 per cent is high, exceeded only by Nordic countries, Germany, New Zealand and the Netherlands among OECD nations. Women's engagement in paid work has increased steadily through the last two decades while men's has declined. However the proportion working more than 30 hours a week is relatively low at 76 per cent, above only Australia and Switzerland. The availability and cost of child care is likely to be an important factor in this. A high level of work participation without an increase in productivity is an inadequate response to globalisation unless wages are kept relatively low.

If it proves difficult to stimulate private investment effectively and labour is already relatively cheap, flexible and docile, a remaining strategy to enhance productivity is to improve labour quality. There have been a large number of educational reforms in the past two decades, mainly centring on school management in the move towards academies and free schools, and to testing. These are long-term measures. Spending on education as a whole is relatively high, exceeding that in the US and in EU members, apart from Nordic countries (OECD, 2014, Annex Figure 2), and participation in tertiary level education is also high – the highest in Europe, with 38 per cent of the population having tertiary qualifications. However, vocational education receives many fewer resources, about 70 per cent of that on students in academic programmes (ibid, 3). Spending on adult vocational programmes was cut by four per cent between 2008 and 2014, the largest cut in the EU (Colebrook et al., Reference Colebrook2015: figure 4.4). Many countries increased spending in this area in response to the recession. The UK also has a larger proportion of 16–29 year-olds neither employed nor in education and training (16.3 per cent in 2012, against 15.2 per cent in the US, 9.9 in Germany and 15.0 in OECED as a whole: OECD, 2014: 7). These statistics have led many to question whether education policy is unbalanced (see Colebrook, ch 4). The UK also increased student fees to £9,000 for most universities following the Browne review in 2010 so that the choice between higher education and work for more academic students is more pointed. University recruitment continues to rise indicating a continuing imbalance between academic and vocational training (UCAS, 2016).

The UK maintains a low-tax, relatively low-labour-cost economy with high employment and weak unions, but lags in productivity. Two factors that may explain the weakness in this area are low investment in capital per worker and low investment in vocational training. This goes hand in hand with an environment in which middle class, more highly educated winners from globalisation prosper while lower class, less-skilled, less-secure and lower-paid workers are left behind. The welfare state regime for the latter has been cut back sharply. One outcome is a deepening division between the two groups. As evidence presented later shows, it is the losers who are most likely to support Brexit.

The second long-term challenge is demographic. Government spending in this area is unlikely to address competitiveness.

Population ageing

The central estimate of population growth by the Office of Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) projects an increase in the proportion of over-65s from 18 to 26 per cent between 2015 and 2065 (OBR, 2016b: chart 2.1). Spending on both pensions and health care is projected to fall as a proportion of GDP during the life of the current parliament, due to rises in GDP, increases in the state pension age and plans to generate substantial cost savings in the NHS. In the longer term, the government's commitment to the ‘triple lock’, uprating state pensions in line with the highest of RPI, earnings or 2.5 per cent will ‘ratchet up average pension payments relative to the economy's capacity to fund them’ (OBR, 2015). This led the Work and Pensions select committee to recommend the dilution of the triple lock to indexation by earnings (HoC, 2016) but the 2016 government has committed to retaining it (Hammond, Reference Hammond2016).

Achieving the savings plan for the NHS is widely regarded as unlikely (King's Fund, 2016a). The service as a whole is currently in deficit (Appleby, Reference Appleby2016). Future NHS directions are currently being decided through five-year Sustainability and Transformation Plans. Most experts agree that health service futures must depend on successful co-ordination of health and community care. While outcomes are as yet unclear, the King's Fund has expressed doubts that the plans will deliver their objectives because they are overly focused on achieving savings and on rationalising the acute hospital sector, and because there is no mechanism to ensure that adequate health and community inter-linking takes place (King's Fund, 2016b).

OBR assumes that pension and health care costs will start to rise again in the early 2020s, as a result of population ageing and technological changes and rising demand for health services. The increased costs in health care are estimated at some two per cent of GDP by 2065 and in pensions at more than 2.5 per cent (OBR, 2016c: chart 3.1; 2016b: chart 4.1).

Such a rate of increase is rather lower than that achieved during the past half-century and may be manageable, assuming that society continues to grow richer and that the austerity programme is slackened to allow health and pension budgets to grow, in conflict with current government policies. However OBR points out that further factors, most importantly failure to achieve future productivity gains on the current scale (Corlett et al., Reference Corlett, Finch, Gardiner and Whittaker2016: Figure 3) and the likelihood that a richer society will demand higher quality provision, may impose an extra six to eight per cent increase in the longer term (2016c). This will impose severe stress.

The 2016 annual report of the Care Quality Commission (CQC) refers to pressures as ‘unprecedented’ and states that ‘the sustainability of adult social care is approaching a tipping point’ (CQC 2016: 7). In relation to hospital services, it concludes: ‘we are concerned about the sustainability of quality’ (CQC, 2016: 9). Despite cash injections, social care services have not enjoyed the same level of protection as the NHS and spending in this area has fallen so that many fewer receive support. The cuts to service spending fell most harshly on local government, which lost about a third of its resources between 2010 and 2015. Local government cuts reduced non-mandatory services enormously and had major impacts even on the statutory responsibilities of social care and children's services. The numbers of over-65s receiving local authority social care services fell by a third between 2009 and 2014 (Burchardt et al., Reference Burchardt, Obolenskaya and Vizard2015). This creates extra difficulties for the NHS due to bed-blocking as hospitals are unable to discharge frail older people. Support through the Better Care fund and through policies that enable local authorities to raise an extra two per cent rate precept for care (which amounts to some three per cent of total local social care spending) are insufficient to bridge the funding gap (King's Fund, 2016c).

In short, the pressures of an ageing population have been contained for a relatively short period at the cost of considerable strain. The kinds of overall structural changes that would guarantee the sustainability of provision in this area have not been pursued. Plans to substitute less expensive delivery of health care in the community for hospital care (currently more than four-fifths of NHS spending) and to introduce an ‘escalator’ into pension commitments so that payments were related to demographic and price shifts have not been implemented, and the capacity of the non-state sector to share the burden is limited. Instead government has addressed immediate problems through one-off cash injections into the NHS and pension age rises. Funding for community care has not been put on a secure basis nor effectively integrated with hospital care and a package to support private care spending and put it on a nationally uniform basis has not been established, despite a series of proposals (Nuffield Foundation, 2016; DH, 2012; Barker, 2014). The overall impact of population ageing policy is to direct a yet higher proportion of constrained spending towards older people, making it more difficult to develop the human and social investment regime necessary to advance the quality of labour.

The UK has managed the immediate pressures from an ageing population with great difficulty and it is unclear how long it will be able to do so. Programmes that favour the old rather than those of working age exacerbate age divisions and do little for productivity. The most striking issue for the UK welfare state is the need to improve productivity in order to compete effectively in a world market, thus increasing resources available to sustain social provision for all age groups. The failure to address the issues of productivity and of improving job quality has contributed to the sense of rejection among those who feel their opportunities are deteriorating.

Short-term pressures: policy choices, poverty and inequality

The immediate crisis of the UK welfare state concerns its core objective: achieving adequate living standards across the population. The UK is relatively unequal and has high levels of poverty for a developed economy, the highest poverty levels in Western Europe at 23.5 per cent of the population in 2015 by the 60 per cent of median equivalized income measures. In Germany rates are 20.0 per cent, in France 17.7, in Sweden 16 per cent. The only European countries with higher rates are Mediterranean or post-socialist (Eurostat, 2016b). Income inequality, as measured by the ratio of the top fifth to the bottom fifth in 2015, is again the highest in Western Europe, 5.2 in the UK, 4.8 in Germany, 4.3 in France and 3.8 in Sweden (Eurostat, 2016a). Since 2010, governments have cut back benefits for the working-age population, by freezing rates, withdrawing benefits for some groups, introducing restrictions on child and housing benefits and reforming disability benefits with the intention of saving a third of projected expenditure (see Hills, Reference Hills2015). OBR describes these cuts as ‘unprecedented’ (OBR, 2016a: 2).

Analysis, by the Institute of Fiscal Studies, of the most recent reforms summarised in the May 2016 budget is that they will impact differentially on the poorest three deciles, cutting their incomes by more than six per cent over the life of the parliament and exacerbating inequality (Elming and Hood, Reference Elming and Hood2016). The most important factor is the freezing of benefit rates, despite the likelihood of an increase in inflation to more than two per cent (Bank of England, 2016).

The measures to address long-term issues of productivity and competitiveness reviewed above (tax policies that have not succeeded in stimulating investment and labour market policies that keep wages down, weaken unions, and mobilise people into paid work through a combination of benefit cuts and the incentive of a slightly higher minimum wage) have failed to slow the rise in poverty.

Patterns of poverty have changed substantially during the past two decades, due to higher participation in paid work (but with greater wage inequalities) and at the same time higher state pensions and greater access to private pensions. Old age and unemployment have become less significant as causes of poverty. ‘The proportion of children living in a household [in poverty] where no-one works has fallen from nearly one in four in 1994–95 to less than one in six in 2014–15’ (Blefield et al., Reference Belfield, Cribb, Hood and Joyce2016: 1). Income from employment made up half of the income of the poorest fifth of households in 2014–15 (excluding pensioners), up from less than a third 20 years ago (ibid.). Poor people are increasingly in work.

Projections into the future, taking account of estimates of growth, inflation and changes in employment, indicate that the trends to working poverty and to greater inequality are likely to continue. Although wage rises will average over one per cent a year, the benefit cuts for lower income workers outlined above will roughly cancel this out. Relative pensioner poverty will remain unchanged, but relative child poverty will rise from 17.8 per cent in 2015–16 to 25.7 per cent by 2020–21, wiping out almost all improvement since 1997–8 (Browne and Hood, Reference Browne and Hood2016: 2). UK labour costs are likely to remain low, so that the argument for investing to improve the quality and availability of labour becomes even stronger.

In short, the UK welfare state faces serious long-term challenges both from globalisation and labour market change and from population ageing. Current policy directions are failing to address those problems, but deepen social divisions and bear most heavily on the most vulnerable groups, leading to higher poverty, particularly among low-paid people who fail to benefit from recent changes. They contribute to disillusion with the political elite among this group, and a perception that the more open markets championed by the EU damage their interests.

Social and political divisions

Social divisions and welfare state policies

The UK polity is a first-past-the-post majoritarian system with two major parties, although new political formations around national identity and green politics have emerged in recent years. In such a system social divisions between winners and losers can be self-reinforcing. If those who believe they are advantaged by a particular policy are sufficiently numerous and well-mobilised to have an impact on voting that exceeds that of the losers, they can command policies that sustain the division to their own benefit, as they see it. There are indications that this ‘winner-takes-all’ (Hacker and Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2010) logic applies across three areas in relation to the UK welfare state: tensions between pensioners and those of working age, particularly those on low wages or unemployed; tensions between better and worse-off; and tensions between immigrants and established residents, often bound up with issues of ethnicity and national identity and of particular relevance to Brexit. Other divisions (between the interests of men and women, between those of different sexuality, and between regions have less effect on social policy and are not discussed here).

The European Quality of Life survey identifies the UK as having the highest levels of tension in Western Europe between old and young people (74.5 per cent report ‘a lot of’ or ‘some’ tension), and coming after France in tension between rich and poor (86.7 per cent) and after only France, the Netherlands and Belgium in tension between racial or ethnic and religious groups (88.9 and 83.7 per cent respectively). These divisions have been reinforced by the way the rapid rise in immigration and asylum seeking in recent years has been managed (see Taylor-Gooby et al., Reference Taylor-Gooby, Leruth and Chung2017).

Social tensions and conflicts damage quality of life. They also provide opportunities for political parties to muster support from the winners in social divisions. This is particularly important in the majoritarian UK, compared with the more consensus-oriented systems common across Europe, which facilitate negotiation and coalition between different groupings (Bonoli and Natali, Reference Bonoli and Natali2012: ch 1).

In the UK, older people are more likely to vote Conservative than younger people. This is reflected in the overt generosity of the current government to the services they most use (the ‘triple lock’ and the repeated promise to ring-fence NHS budgets) in contrast to the major cuts elsewhere. Spending on pension benefits was close to that on non-pension benefits in 2010 at 7.8 and 7.4 per cent of GDP respectively. By 2016, the percentages were expected to have diverged to 8.2 and 5.9 per cent, reflecting cuts in benefits for younger age groups and support for older groups (Eurostat, 2016a). In practice, increases in retirement age more or less cancel out the cost of the triple lock and cuts to social care and housing budgets mean that total spending on older people is projected to decline as a proportion of GDP, but more slowly than spending on younger people (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2016: figure 10). However, as pointed out above, this is a short-term fix: spending will rise in relation to GDP in the longer term and, all things being equal, deepen the deficit.

The age strategy is successful in gaining political support. In the 2005 election, 29 per cent of those aged 55 or over declared an intention to vote Conservative as against 24 per cent for Labour. By 2015, the percentages were 34 and 23 per cent (Ipsos-Mori, 2015 and 2010). The effect is redoubled because older people are roughly twice as likely to actually cast their votes as younger people.

Further divisions in policy for working-age people between those in employment and those out of it are reflected in the move from National Minimum Wage to a slightly higher National Living Wage and the increases in the income tax threshold, set against the transition to Universal Credit, the tightening of the ‘benefits cap’ and the associated benefit cuts. The new policies ensure that those on benefits receive substantially less than low-paid workers in work: for a family of two adults (both unemployed) and two children, benefit income was equivalent to 61 per cent of median earnings (assuming both worked full-time) in 2010, but had fallen to 57 per cent by 2014 (OECD, 2016b). This gap will widen as the freeze in benefit rates from April 2016 (Turntous, 2016) affects unemployed people at a time when wages are expected to rise.

These policy differences appear to be reflected in voting. While good data on voting by benefit claimants is not conveniently available, 45 per cent of middle class AB people declared an intention to vote Conservative in 2015 as against 26 per cent for Labour, a wider party gap than the 37 and 28 per cent in 2005.

The recent rise in immigration from EU and non-EU countries has been particularly vulnerable to politicisation. Immigration fluctuated between two and three hundred thousand a year between the early 1970s and late 1990s and then rose rapidly to over 600,000 a year, chiefly as the result of the accession of new EU members and the impact of Middle Eastern wars (ONS, 2017). This has led to real concerns among traditionally right-wing and also among traditionally Labour-supporting working class voters about competition for jobs, housing and school places (Dustmann et al., Reference Dustmann, Fasani, Frattini, Minale and Schӧnberg2016). Among black and minority ethnic voters (categorised as one group, due to the relatively small numbers in the Ipsos-Mori survey sample) 23 per cent intended to vote Conservative, versus 65 per cent Labour, compared to 14 and 64 per cent in 2010. Conservatives gained ground among older, middle class and black and minority ethnic voters. Net migration fell by about 50,000 between July and September 2016 after the Brexit vote, half the change due to a fall in immigration and half to a rise in emigration, shared equally between EU and non-EU citizens (ONS, 2017: Figure 2). These figures are highly provisional but may indicate that the referendum outcome is having an impact.

Divisions in relation to age and working status can be seen in terms of the coincidence of interest and ideology. Since the establishment of welfare states, by far the lion's share of provision has been directed to the needs of older people. The interests of the mass population who feared poverty when they were too old to work, were reinforced by those of employers who found pensions helpful in the process of replacing older workers with more energetic, highly skilled and cheaper younger workers. The needs of old age have traditionally topped the list of deserving areas of social provision (Coughlin, Reference Coughlin1980; Cook, Reference Cook1979; Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2015: 13). Old age dependency has risen from 299 over 65s for every 1000 population in 1990 to 307 currently and is expected to reach 395 by 2065 (ONS, 2016). Conversely those of working age have lost out, and this is indicated by two developments bound up with changes in labour process and sectoral shifts away from manufacturing: the long-term fall in the share of growth going to workers, evident in advanced countries since the late 1960s (OECD, 2015b) and the declining influence of labour, encapsulated in the fall in union membership. Union membership peaked at about 50 per cent in the UK in the mid-1950s and has now fallen to below half that (OECD, 2015a).

These divisions are reinforced by the conflict between immigrants and nationals, linked to conflicts between dominant and minority ethnic, racial and religious groups and to divisions of interest. Kriesi and others argue that, in general, the better educated, more highly skilled and wealthy do well out of more open markets and are in a position to grasp the opportunities brought by globalisation (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Hoglinger, Hutter and Wuest2012; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2013). The less fortunate, skilled and supported do worse. Hence it is the latter group who provide a fertile recruiting ground for anti-immigrant politics (Ford and Goodwin, Reference Ford and Goodwin2014) and for anti-EU campaigns (Van Elsas et al., Reference Van Elsas, van der Brug and Hakhverdian2016; Hakhverdian et al., Reference Hakhverdian, Van Elsas, Van Der Brug and Kuhn2013).

Globalisation can be represented as an opening up of the national economy to competitive market forces and of national borders to immigration (Davies, Reference Davies2016). UK governments have failed to develop policies which compensate the losers from these processes or improve their skills and productivity so that they can grasp opportunities from it. The divisive short-term policies which sustain government popularity, but do little to address long-term problems, bear most heavily on those who lose out from structural changes in the economy. The losers from globalisation are open to political movements which assert national identity and strong national control of borders as the most relevant response and fuel their antagonism to institutions identified with market openness and free movement, such as the EU. From this perspective, the divisions that surrounded the Brexit vote are based on the experience of globalisation as an oppressive force and the desire for strong national government to protect more vulnerable individuals who see themselves as losing ground to external forces.

This perspective is reinforced by what we know about differences between Leave and Remain voters. There are two main kinds of evidence available: attitude surveys and data on voting patterns by ward, which can be related to demography, politics, degree of deindustrialisation and the impact of spending cuts. The attitude data for the period before the referendum paints a picture of voter opinion as sharply divided by both cultural and socio-demographic factors: national identity, attitudes to immigrants and attitudes to the EU and to the UK governing elite, as well as social class, age, area of residence, occupation and level of education and skill (Swales, Reference Swales2016; Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2016).

All attitude surveys agree on three points: there are clear socio-demographic differences between Leave and Remain voters or intending voters. The group most decisively supporting leave tends to be more working class, less well educated, lower skilled and to live in de-industrialising and northern areas. Earlier work (for example, analysis based on BSA 2015) also identifies an older more middle class group distinguished by strong national identity that tends to support exit (Swales, Reference Swales2016). Secondly, there are clear differences in values and beliefs: Leave voters are more concerned about the damage they believe immigrants do to the economy and more likely to see immigration from the EU as essentially a burden. They are also more likely to believe that leaving will benefit the British economy (Natcen, 2016). Thirdly, the Leave campaign gained ground in the run-up to the vote and was more successful in getting supporters, who held their views more strongly, (Swales, Reference Swales2016) to vote (Curtice, Reference Curtice2015).

The main differences lie in the relative importance of cultural factors and identity politics: the pre-referendum surveys are more likely to point to the importance of the former. This suggests that some of the earlier data which is widely used (in particular from the 2015 British Social Attitudes (BSA) and British Election Surveys and commercial polls) may not tell the full story. There are also polls conducted very close to the 23 June referendum by Hobolt and Wratil (Reference Hobolt and Wratil2016) and shortly after the date by BSA (Curtice, Reference Curtice2016).

Hobolt and Wratil's YouGov survey of 5000 voters conducted in May 2016 shows a clear division between the way ‘Leave’ and ‘Remain’ voters understood the issues: while the former expressed concerns about immigration and lack of trust in the UK government and the EU, the latter stressed economic benefits (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016: Table 1): ‘fears of immigration and multiculturalism are more pronounced among voters with lower levels of education and in a more vulnerable position in the labour market. Such voters also voted most decisively for Leave, whereas the ‘winners’ of globalization – the younger and highly educated professionals – were overwhelmingly in favour of Remain,’ (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016: 1273). Further analysis of a sub-group of 1396 BSA 2016 participants, re-interviewed after the referendum, also shows very clear differences in the understanding of Leave and Remain voters on how Brexit will affect the UK (Curtice, Reference Curtice2016).

Post-referendum studies of the distribution of the vote deal with socio-demographic factors and local circumstances. A thorough study by Becker and colleagues reports:

. . .the share of the population aged 60 and above as well as the share of the population with little or no qualifications are strong predictors of the Vote Leave share. Furthermore, areas with a strong tradition of manufacturing employment were more likely to Vote Leave, and also those areas with relatively low pay and high unemployment. We also find strong evidence that the growth rate of migrants from the 12 EU accession countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 is tightly linked to the Vote Leave share.. . . In addition, we find that the quality of public service provision is also systematically related to the Vote Leave share. In particular, fiscal cuts in the context of the recent UK austerity programme are strongly associated with a higher Vote Leave share. We also produce evidence that lower-quality service provision in the National Health Service is associated with the success of Vote Leave. (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2016, 38–9)

This leads to the conclusion that:

In terms of policy conclusions, we argue that the voting outcome of the referendum was driven by long-standing fundamental determinants, most importantly those that make it harder to deal with the challenges of economic and social change. They include a population that is older, less educated and confronted with below-average public services. (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2016: 39)

The evidence is complex, limited and of varying quality. Overall it supports the approach of this article, that Brexit is best understood as a response to long-term structural factors as they are understood by the population, rather than cultural issues, exacerbated by recent policies. The groups most affected by globalisation and labour market change and deindustrialisation, who were least well served by policies which favour the better off and pensioners, were much more likely to vote Leave. We move on to consider how exit from Europe will affect social divisions in the future.

The impact of Brexit

Brexit negotiations appear likely to go ahead despite the fact the June 2017 election result dramatically weakens the UK's position. The UK government wishes to have control over EU immigration, a continuing close relationship with the EU market and also much more open market relationships globally. Whether these objectives are compatible is unclear, and the precise impact on British voters especially those who supported Brexit must depend on the outcome of negotiations and the extent to which new government policies redirect resources to improving their skills and opportunities (DEEU, 2017). Here we comment on possible economic and political effects.

The UK government gained House of Commons support for its Brexit policies at the third reading of the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill 2016–17 and went ahead with initiating withdrawal on 30 March 2017 (BBC, 2016).

Brexit-sceptics point out that the ruling Conservative party gains very substantial support from the finance sector (possibly half of its funding: Financial Times, 2015), and that a thorough-going withdrawal is highly likely to damage the capacity of this sector to trade across Europe (MacShane, Reference MacShane2016; Brooks, Reference Brooks2016). A possible outcome is that the terms of exit are so diluted as to generate continuing conflicts over the influence of the EU on the UK and over control of borders. In any case, the government has signalled a liberal commitment to open markets and economic globalisation so that the pressures on winners and losers from labour market change will continue and the competitiveness imperative will, if anything, be strengthened.

Assuming Brexit is pursued, the only economic fact we have is the fall of the pound in international markets, by 15 per cent against the Euro over the last twelve months (London Stock Exchange, 2017). Short-term predictions by ONS suggest a slow-down in growth (but not a recession) and a rise in inflation to 2.5 per cent by 2018–19 (Corlett et al., Reference Corlett, Finch, Gardiner and Whittaker2016: Table 1). These changes will increase export opportunities, reduce earnings and domestic consumption and intensify the impact of the benefit freeze on the working-age welfare state. Without a sharp reversal of current policies, they will deepen the divisions between old and young and those in and out of work noted above.

In the longer term, outcomes are likely to lie between an optimistic and a pessimistic scenario.

Optimistic

An optimistic scenario would require the UK to develop short-term policies that help address the long-term crises of competitiveness, investment, poverty and inequality. Recent policies fail to address any of these issues but have bought time in relation to population ageing at the cost of higher retirement ages and considerable damage to the interests of other age groups. A positive outcome would require investment in education and training capacity and in research and development to support competitiveness. In any post-Brexit world the UK seems unlikely to have the ease of access that it currently enjoys to the markets of the most developed and convenient regional economies, although it may gain an improved access to a broader highly competitive world market where wages are lower in many participant countries. This suggests that the gap between winners and losers will widen. One possibility is a sharp reduction in living standards in the UK, especially for the least educated and those working in industries with low levels of investment. Government could take the opportunity to compensate losers and to improve the quality and utilisation of workers’ skills.

In addition to greater support for productive services, provision for the needs of older people through transfers and health and social care services will need to expand. This requires extra resources in staff and finance. It is difficult to see how more workers in the health and care industries can be provided without ensuring that the country remains attractive to immigrants with the relevant skills. A recent EU Health Observatory report shows that some ten per cent of doctors in the UK were from EU countries and 28 per cent from elsewhere abroad (Buchanan et al., Reference Buchanan, Wismar, Glinos and Bremner2014: 277). About six per cent of the adult care workforce is from EU countries and about 12 per cent from elsewhere (Skills for Care, 2016).

The decline in the value of the pound will stimulate exports and act as a brake on imports. The International Monetary Fund predicts that the balance of payments deficit will fall from about six to about four per cent of GDP by 2020, largely as a result of the devaluation (IMF, 2016). Devaluation, however, will not in itself address the problems caused by low productivity.

Improvement in labour capacity demands investment in education, especially in training and in lifelong learning and skills renewal. In the longer term it may be that improvements in work-force quality will feed through into higher productivity, higher employment and better wages, summed up in the aspirations of the EU 2000 Lisbon Conference for: ‘the most dynamic and competitive skills based economy in the world’ at EU level (EU, 2020). Investment in employment opportunities will also be required and here the role of a state-funded investment bank could be important. Some extra finance for these policies and for health and social care could be provided by reversing some tax cuts particularly at the top end, but any attempt to provide major new funding will require a move towards borrowing to expand social investment. The new apprenticeship programme from April 2017 (DfE, 2017) may go some way towards providing this by tapping substantial extra finance (up to £2.5bn) from a levy on employers, but sceptics point out that the quality of most apprenticeships has been diluted (Crawford-Lee, Reference Crawford-Lee2016; Saraswat, Reference Saraswat2016).

Productive work requires good working conditions, including parental rights and bargaining power to ensure any increase in productivity feeds through into better pay. Some will always lose out and this requires benefits adequate to meet people's needs plus support and opportunities to enter work. The optimistic scenario sees the government investing heavily in its workforce and in its social provision, in national productive capacity and technology to ensure that the country prospers when it confronts the world market directly. It is possible that greater equality between old and young, better opportunities for most people, and a rise in real wages at the bottom could help heal some of the divisions in our society. It is clear that this programme comes as a package. Growth and productivity-oriented policies require better training and investment and in turn generate the resources that can be used to help more vulnerable groups.

Pessimistic

The converse direction is that the UK continues to drift towards a future of sharper social divisions. If government continues to focus primarily on short-term objectives and does little to address the long-term crises, these crises will deepen and the cost of tackling them become more formidable. The pessimistic scenario envisages a failure to address issues concerning the quality of the workforce, the opportunities available to people and investment in business, so that productivity remains relatively low and the UK can only compete by cheapening labour. Living standards fall, especially for the losers, it becomes more difficult to raise the taxes necessary to finance good services for older people and others in need, and the welfare state withers. It is likely that competition for available resources will grow more intense as the total quantity falls, and opportunities for politicians to win elections by capitalising on discontents and divisions expand. The negative scenario is one of contraction and further conflict.

Drivers of change

We have argued that the division between winners and losers from the economic and social transformations of our time lies behind the Brexit vote, and that Brexit is likely to depress living standards for those in the weakest competitive position in the world market and deepen that division. A withdrawal from EU trade is likely to damage growth prospects. Petrongolu (Reference Petrongolu2016) points out that the ‘average hourly wage in the 15 UK industries with the highest concentration of immigrants from the 2004 accession countries is £9.32, significantly below average UK-born wages of £11.07’. This suggests that, if a greater proportion of UK workers move into those jobs, average wages for UK workers will fall or the jobs will remain unfilled. Reduced immigration will impact on living standards. This may lead to further disillusion with the political elite and policy-makers and deepening political instability.

Conclusion

This article has argued that the political context of policy making in the UK militates against effective strategy-building to tackle the long-term structural issues of globalisation and population ageing and that this lies behind enthusiasm for Brexit among some groups. Recent government responses have failed to address these issues, have diverted attention from them and, in some ways, exacerbated them. These policies have reinforced divisions between old and young, winners and losers from globalisation, and nationals and immigrants. One outcome has been the visceral rejection of globalisation and the embracing of a chauvinist and protective nationalism that contributed powerfully to the vote against EU membership, understood as a vote against globalisation and open borders and against remote and mistrusted government by those who believe that the political class no longer has their interests at heart. It is unclear how current policies will do anything to address these issues or redress the profoundly unequal impact of globalisation and technological change on life-chances or whether the June 2017 election outcome will lead to a substantial difference in direction.

One possibility is that the experience of exit from the EU generates support for national policies that compensate losers from globalisation and equip the workforce, particularly at the bottom end, to compete successfully in an international marketplace. Indeed the shock of exit might provoke a national debate that makes it politically feasible to direct policy towards these goals over the life of several parliaments. Another is that it fails to do so and continues the current trajectory of poverty and inequality and a weaker national capacity to address longer-term problems, the double crisis writ large. It is entirely unclear where the tipping-point between the two responses lies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NORFACE project Our Children's Europe, ref 462-Reference Corlett, Finch, Gardiner and Whittaker14-050.