No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

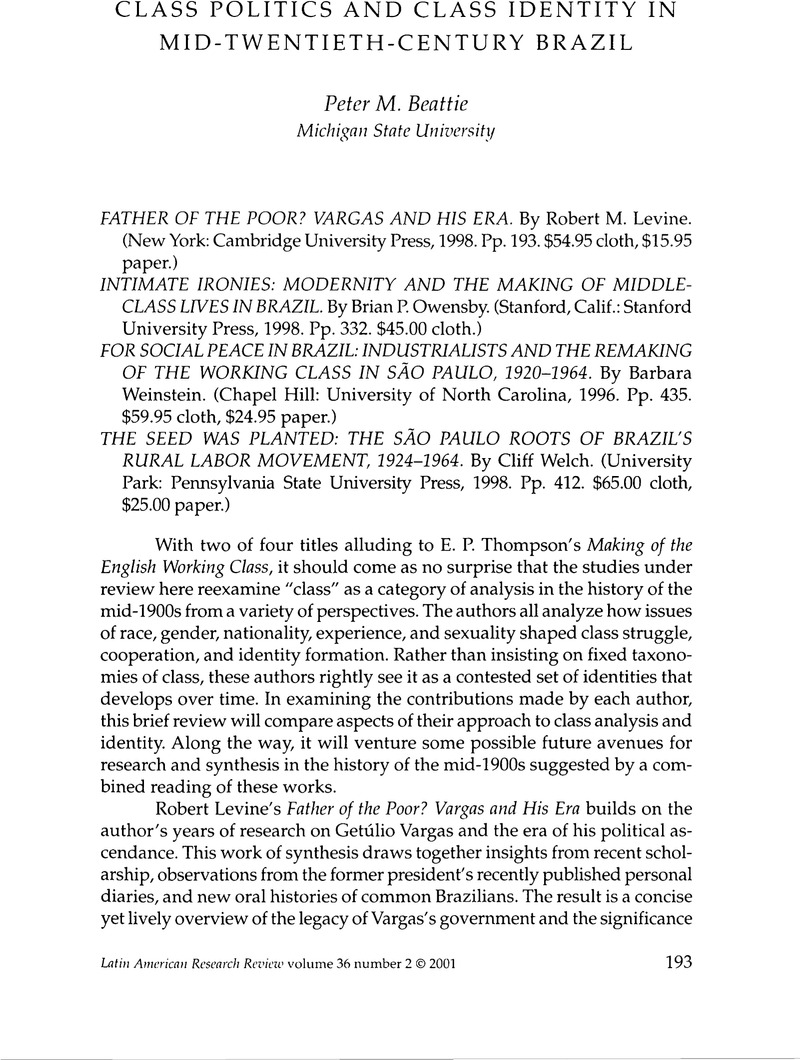

Class Politics and Class Identity in Mid-Twentieth-Century Brazil

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2001 by the University of Texas Press

References

1. For a recent critique of the use of the concept of “false consciousness,” see James Scott, Dominance and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1990).

2. See for example Alice Beatriz da Silva Gordo Lang, “Getúlio Vargas: Marcas de memórias nas mulheres paulistas,” História Oral 1, no. 1 (June 1998):145–67; also Levine and John Crocitti's inclusion of oral history in “Ordinary People: Five Lives Affected by Vargas-Era Reforms,” in The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics, edited by Levine and Crocitti (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1999), 206–21.

3. Verena Stolke, Coffee Planters, Workers, and Wives (New York: St. Martin's, 1988).

4. Here I echo a plea made earlier by Todd Diacon in “Down and Out in Rio de Janeiro: Urban Poor and Elite Rule in the Old Republic,” LARR 25, no. 1 (1990):243–52. Bert Barickman's recent work on the rural history of the Recôncavo in the 1800s points to numerous questions in rural labor that can only be resolved through further work on the subject in the 1900s. For instance, Barickman found that land suitable for subsistence agriculture was plentiful in the 1800s. He has suggested that lack of access to land for small producers can be more fully understood only through investigations of agricultural production and rural labor in the 1900s. See Barickman, A Bahian Counterpart: Sugar, Tobacco, Cassava, and Slavery in the Recôncavo, 1780–1860 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1998), 190.

5. For example, see Daniel Orlovsky, “The Hidden Class: White-Collar Workers in the Soviet 1920s,” in Making Workers Soviet: Power, Class, and Identity, edited by Lewis Siegelbaum and Ronald Suny, (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1994), 220–52.

6. On the politics of anti-politics among Latin American military officers, see Brian Loveman, For La Patria: Politics and the Armed Forces in Latin America (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1999). On the hypocrisy of the military's rhetoric on corruption, see Shawn C. Smallman, “Shady Business: Corruption and the Brazilian Army before 1954,” LARR 32, no. 3 (1987):39–62.