No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

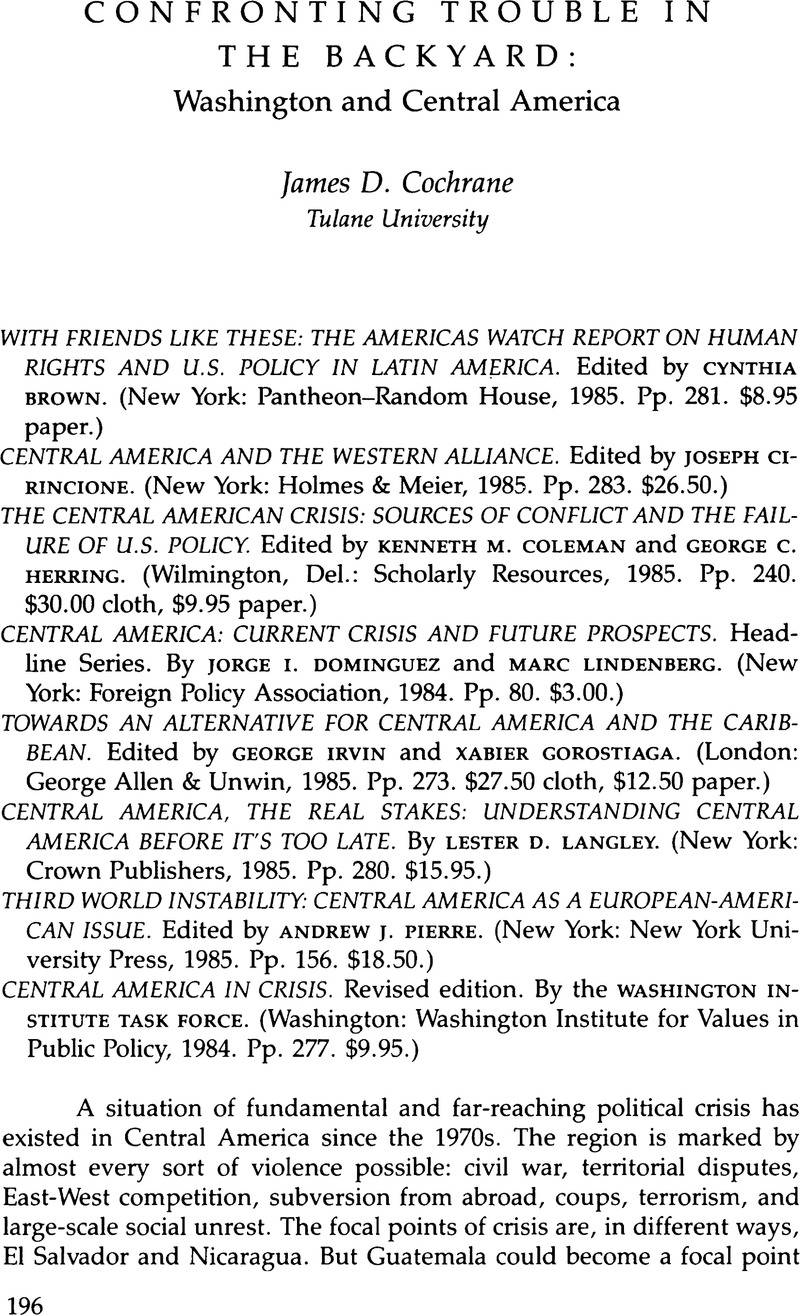

Confronting Trouble in the Backyard: Washington and Central America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1987 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Richard Millett, “Praetorians or Patriots? The Central American Military,” in Central America: Anatomy of Conflict, edited by Robert S. Leiken (New York: Pergamon Press, 1984), 83.

2. This essay does not consider Belize and Panama as part of Central America. Recently independent Belize, despite its being geographically part of Central America, is in orientation much more a part of the Commonwealth Caribbean. Panama, often treated as a Central American country, is historically and geographically more South American than Central American.

3. Also, see Jorge I. Domínguez, U.S. Interests and Policies in the Caribbean and Central America (Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1982). Other identifications of U.S. interests in Central America are to be found in The Report of the President's National Bipartisan Commission on Central America (New York: Macmillan, 1984), 45; Howard J. Wiarda, In Search of Policy: The United States and Latin America (Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1984), 24–25; and Margaret Daly Hayes, “Coping with Problems That Have No Solution: Political Change in El Salvador and Guatemala,” in Confrontation in the Caribbean Basin: International Perspectives on Security, Sovereignty, and Survival, edited by Alan Adelman and Reid Reading (Pittsburgh: Center for Latin American Studies and University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 1984), 38. In addition, see Hayes's Latin America and the U.S. National Interest: A Basis for U.S. Foreign Policy (Boulder: Westview, 1984). The interests identified in these sources are generally in line with those cited by Domínguez and Lindenberg. All lists concur that keeping hostile powers out of the region is the paramount U.S. objective.

4. The article is an updated version of Kenworthy's paper published in World Policy Journal 1 (Fall 1983):181–200.

5. The Report of the President's National Bipartisan Commission on Central America, 111.

6. Many other students of the Central American crisis agree, among them: James Chace, Endless War (New York: Vintage–Random House, 1984); Walter LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983); and most, if not all, of the contributors to Trouble in Our Backyard, edited by Martin Diskin (New York: Pantheon-Random House, 1983), and The Future of Central America: Policy Choices for the U.S. and Mexico, edited by Richard R. Fagen and Olga Pellicer (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983).

7. One part of that prescription would be difficult for Washington to implement, if it decides to do so. It is through the traditional elite that the U.S. has exerted its influence in Central America and Latin America generally. See U.S. Influence in Latin America in the 1980s, edited by Robert Wesson (New York: Praeger, 1982), especially the introduction.

8. Some of the contributors to Diskin's Trouble in Our Backyard and Fagen and Pellicer's The Future of Central America would agree with LaFeber, as would those who subscribe to an explicitly dependista interpretation of U.S.–Latin American relations.

9. To be sure, some who posit external actors as the cause do not have Havana and Moscow in mind. They point to the United States as a substantial, although not exclusive, cause. One example is Luis Maira, who writes: “One should not underestimate the degree to which the current crisis in Central America relates directly to prolonged U.S. government support for authoritarian regimes in the area, despite signs of their obvious illegitimacy, exhaustion, and disintegration. The present situation was reached only after a series of endogenous democratization and modernization projects had been derailed by the regimes of force in the sixties and seventies. Washington did nothing to impede this.” See Luis Maira, “Reagan and Central America: Strategy through a Fractured Lens,” in Diskin, Trouble in Our Backyard, 39.

10. This statement is yet another instance of the Reagan administration's rhetorical excess concerning Central America. It is highly unlikely that “the overwhelming majority of Central Americans want democracy.” The fact is that the overwhelming majority of Central Americans have no experience with democracy, never having lived under a democratic government nor studied democracy as a political theory. After years of political turmoil, the vast majority of Central Americans probably do not want to fight for anything but want instead to be allowed to live their lives in peace. Further, it is far from clear when Washington speaks of democracy in the context of the Central American crisis whether it uses the term as generally understood in the United States or as a “code word” meaning “friendly to the United States.” Although U.S. government officials at times speak of democracy, elections, and pluralism in reference to Central America as if those concepts have the same meaning there as in the United States, very often, they do not. For an excellent discussion of what such concepts mean in Central America and in Latin America generally, see Glen Dealy, “Pipe Dreams: The Pluralistic Latins,” Foreign Policy 57 (Winter 1984–85):108–27.

11. See statements by the president, the secretary of state, and other administration officials concerning Central America in the Department of State Bulletin from January 1981 on. This conceptualization of the crisis was previously enunciated by Ronald Reagan in his 1980 campaign for the presidency.

12. The Report of the President's National Bipartisan Commission on Central America, 36.

13. Jiri Valenta and Virginia Valenta, “Soviet Strategy and Policies in the Caribbean Basin,” in Rift and Revolution: The Central American Imbroglio, edited by Howard J. Wiarda (Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1984), 198. That claim either deliberately plays down the realities of the Central American crisis or reflects a lack of proper understanding of them. The engagement of Cuba and the USSR in the Central American crisis inevitably complicates the situation and its resolution. Even with those actors removed, however, a complex, knotty situation would remain that would not be markedly easier to resolve.

14. H. Michael Erisman, “Colossus Challenged: U.S. Caribbean Policy in the 1980s,” in Colossus Challenged: The Struggle for Caribbean Influence, edited by H. Michael Erisman and John D. Martz (Boulder: Westview Press, 1982), 20.

15. It is a point made by others, including Cole Blasier in The Giant's Rival: The USSR and Latin America (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1983), 154.

16. A summary examination of the historical roots of the contemporary Central American crisis can be found in Ralph Lee Woodward, Jr., “The Rise and Decline of Liberalism in Central America: Historical Perspectives on the Contemporary Crisis,” Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs 26 (Aug. 1984):291–312.

17. The emergence of political violence and internal war in Central America followed closely the sequence described by T. R. Gurr in Why Men Rebel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970). He posits the following sequence: first, the development of discontent or alienation within society; second, the politicization of that discontent; and third, the politicized discontent is manifested in violent action directed against political objects and political actors.

18. It is a conceptualization that various others formulate. See Roland H. Ebel, “The Development and Decline in the Central American City State,” in Wiarda, Rift and Revolution, 70–104; Roland H. Ebel, “Political Instability in Central America,” Current History 472 (Feb. 1982):56–59, 86; Howard J. Wiarda, In Search of Policy: The United States and Latin America (Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1984); and Howard J. Wiarda, “The Central American Crisis: A Framework for Understanding,” AEI Foreign Policy and Defense Review 9 (1982):2–7.

19. On this point, see the observations of Thomas P. Anderson, “The Roots of Revolution in Central America,” in Wiarda, Rift and Revolution, 7–8.

20. Luis Maira, “The U.S. Debate on the Central American Crisis,” in Fagen and Pellicer, The Future of Central America, 88.

21. Wiarda, “The Central American Crisis,” 5.

22. This explanation of why a situation of political crisis prevails in Central America is dealt with extensively in James D. Cochrane, “Perspectives on the Central American Crisis,” International Organization 39 (Autumn 1985):755–77.

23. H. Michael Erisman, “Contemporary Challenges Confronting U.S. Caribbean Policy,” in The Caribbean Challenge: U.S. Policy in a Volatile Region, edited by H. Michael Erisman (Boulder: Westview Press, 1984), 6.

24. William LeoGrande, “Through the Looking Glass: The Kissinger Report on Central America,” World Policy Journal 1 (Winter 1984):283.