No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

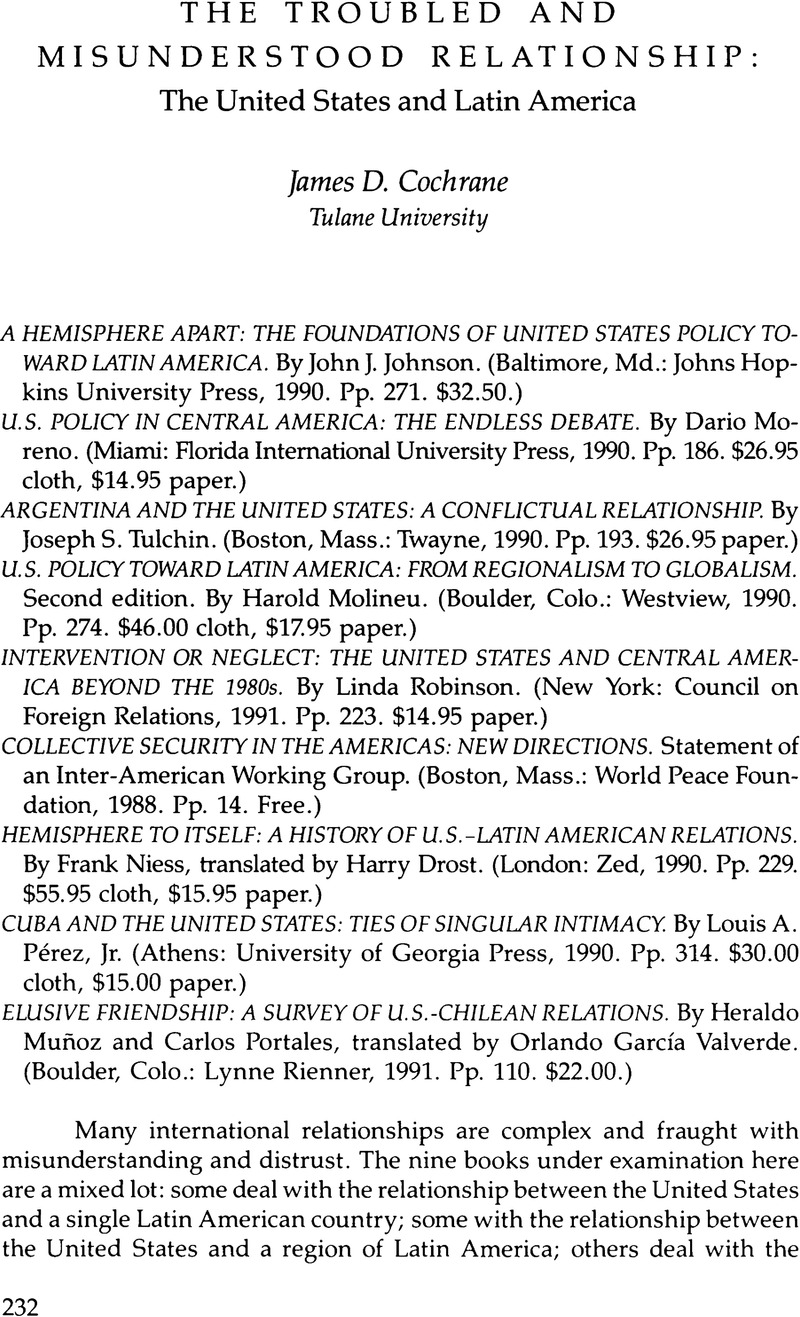

The Troubled and Misunderstood Relationship: The United States and Latin America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1993 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. J. Lloyd Mecham, A Survey of United States Latin American Relations (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), chap. 3.

2. Abraham F. Lowenthal, “The United States and Latin America: Ending the Hegemonic Presumption,” Foreign Affairs 55 (Oct. 1976): 199–213.

3. Not all authors would agree that the United States has acted as hegemon for all of Latin America for two centuries. See James R. Kurth, “The United States, Latin America, and the World: The Changing International Contest,” in The United States and Latin America in the 1980s: Contending Perspectives on a Decade of Crisis, edited by Kevin J. Middlebrook and Carlos Rico (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986), 61–86.

4. Exceptions to that generalization can be cited, and Molineu would probably concur because the exceptions are in line with the overall thrust of his propositions.

5. This goal has been mainly a post-World War II phenomenon. It has been aimed at real or perceived Soviet-sponsored subversion or Cuban subversion backed by Moscow. But this goal has also surfaced at other times in reference to other powers.

6. This point is generally true, but there are exceptions. In the early 1960s, when the United States did not have especially close relations with Brazilian governments, it maintained cordial relations with the Brazilian military. Similarly, while the United States did not maintain friendly relations with the Allende government in Chile, it maintained very cordial relations with the Chilean military.

7. To be sure, the United States does not look with favor on the nationalization or expropriation of private U.S. investment in Latin America (or anywhere else). It has, however, largely accommodated itself to that practice in Latin America. See Paul E. Sigmund, Multinationals in Latin America: The Politics of Nationalization (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1980).

8. Promotion of democracy has really been a secondary U.S. objective vis-à-vis Latin America, despite official U.S. verbiage to the contrary. It is an objective that Washington desires but pursues vigorously only in times of noncrisis. See Howard J. Wiarda, In Search of Policy: The United States and Latin America (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1984).

9. On the breakdown of the foreign-policy consensus, see the authoritative work of Ole R. Holsti and James N. Rosenau, American Leadership in World Affairs: Vietnam and the Breakdown of Consensus (Boston, Mass.: Allen and Unwin, 1984).

10. See Report of the President's National Bipartisan Commission on Central America (New York: Macmillan, 1984). Also see William LeoGrande, “Through the Looking Glass: The Kissinger Report on Central America,” World Policy Journal 1 (Winter 1984):181–200.

11. It is difficult to disagree with these recommendations, but the solution to the drug problem in the United States is that of usage and demand, not supply.

12. This recommendation is a fine one, but it runs counter to the military tradition entrenched in Central America (except in Costa Rica). That tradition thrives with or without U.S. military aid, and thus the United States cannot change it even by reducing military assistance.

13. See James D. Cochrane, The Politics of Regional Integration: The Central American Case (New Orleans, La.: Tulane Studies in Political Science, 1969).

14. Economic integration is a sound recommendation, but it must not wholly follow the free-market model of the Central American Common Market of the 1950s and 1960s. See ibid.

15. The full-length version, edited by Richard J. Bloomfield and Gregory F. Treverton, was published in 1990 by Lynne Rienner in Boulder, Colorado.

16. On political culture and foreign policy, see Roland H. Ebel, Raymond Taras, and James D. Cochrane, Political Culture and Foreign Policy in Latin America: Case Studies from the Circum-Caribbean (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1991).