Introduction

I first encountered Santali, an Austro-Asiatic language with around six million speakers dispersed throughout eastern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, in a nondescript block of flats in the far north end of the eastern Indian metropolis of Kolkata. There, I discovered stacks of magazines, newspapers, and books written in a language that had arrived there from various parts of West Bengal, Jharkhand, Orissa, and Assam. I found surprising the sheer amount of written material in the language. Even though Santali is India's largest spoken Austro-Asiatic language, and one of the official languages of India, it still suffers from a lack of public recognition. In any state where Santali is spoken, there is little public education offered in the language. In urban areas such as Kolkata, many majority Bengali speakers consider the language as simply a ‘dialect’ of rural Bengali. In rural areas, where most Santals reside, upper-caste Hindus continue to refer to the language as ṭhar, or the grunting sounds akin to the vocalizations of those with speech or hearing disabilities.

Most Santali speakers in India are considered by the Indian government as ‘Scheduled Tribe’, a special constitutional category reserved for communities seen as exhibiting ‘primitive traits, distinctive culture, shyness of contact with the community at large, geographical isolation, and backwardness’.Footnote 1 The political designation many members of Scheduled Tribes throughout India have adopted for themselves is ‘Adivasi’ (original inhabitant). Scheduled Tribe communities continue to suffer discrimination on the basis of their perceived ‘primitive’ characteristics, even if their languages and cultures, in some cases, are legally recognized and protected. For instance, the Santali language gained constitutional recognition as a national language of India in 2003,Footnote 2 yet is still associated by many with rural, non-standard, and non-written speech characteristic of lower caste sociolects, even among scholars and those in the realm of policy-making. It is in this social and political milieu, marked by divisions of caste and language both in relation to urban–rural divides as well as within rural communities themselves, where Santali-language writing and the production and circulation of printed media artefacts, such as magazines and newspapers, have become an especially crucial feature of political assertion. This assertion occurs in a direct dialogic engagement with Santali-speaking and other Adivasi communities’ designation as ‘primitive’, a category shaped by colonial and nationalist ethnological discourses. The designation has paradoxically served as a guarantor of rights while also perpetuating the stigma of backwardness and illiteracy.Footnote 3 In order to combat this stigma and reformulate the grounds on which rights and recognition are demanded within the caste and language-divided social landscape of contemporary India, many Santals have been actively engaged in publishing print media in their language, modifying extant Indian scripts such as Devanagari, Eastern Brahmi, and Roman,Footnote 4 but also developing new orthographies, such as the independent Santali script known as Ol-Chiki.

The large number of people I met in Kolkata involved in producing and disseminating Santali-language texts during my research period (2009–2011) attests to the importance of print for Santali political assertion. At every gathering or rally (including rallies for the promotion of Santali language and the Ol-Chiki script), Santali cultural programmes, or celebrations of important events in Santal history such as the Hul,Footnote 5 magazine stalls were set up and a variety of back issues of Santali-language periodicals were sold. This was all the more surprising considering Santali-language education was not widely available in West Bengal, either in Kolkata or in the rural areas of southwestern West Bengal or Jharkhand, where many migrants originated from. Moreover, there was no mass market for Santali-language publications. When I left the urban space of Kolkata and began research in the rural areas of southwestern West Bengal, I realized that even though there were numerous (if not more) people involved in the production and dissemination of Santali-language magazines, the importance of these magazines could not be understood unless seen as part of larger social and political networks that link together a range of communicative practices constituting assertions of Santali autonomy. Thus, rather than see the media domain as a window into a unified ‘national’ community in an Andersonian sense, or through a lens of production or reception, I view the printed text artefact as a constellation of social, linguistic, and—importantly in the case of Santali—graphic practices. These artefacts are recontextualized within networks of circulation, creating new forms of politics.

While there has been a robust scholarship on the significance of language politics in colonial and post-colonial South Asia,Footnote 6 this scholarship has often overlooked the role of material production and graphic technologies in mediating and, in many cases, constituting political claims based on language, region, caste, or community. In this article, I argue that assemblages of technologies, political institutions, and practices of exchange have rendered both language and script as central to historical assertions of autonomy and a contemporary politics of authority among Santals.Footnote 7 I do so by tracing the history of Santali print and assertions of autonomy in colonial and early post-colonial India. I link this genealogy of print technology to a contemporary politics of authority tied to graphic production within local Santali-speaking and reading communities. In the first part of this article, I chart how the setting up of a printing press and the creation of a unique, Roman-based alphabet for Santali by Scandinavian missionaries in the late nineteenth century contributed to the creation of a network of Santali-language readers, connecting mission institutions across eastern India through extant networks of hospitality. I describe the ways in which the organization of states along linguistic and graphic lines, separating the Santali-speaking area into the states of Bihar-Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Orissa, reconfigured these networks, aiding in the creation of a new Santali consciousness around language and script as part of a wider struggle for an Adivasi-majority state of Jharkhand, and leading to the creation and dissemination of a unique Santali script known as Ol-Chiki. In the second part, I trace magazine production across multiple generations in a small region of Purulia district, southwestern West Bengal, documenting how a Santali-language media has empowered a certain class of Santali-speakers, which resulted in the creation of multi-generational social networks and new forms of contested authority in Santal villages around issues of language and culture. Moreover, I analyse how new assemblages of script and technology have transformed and sustained these local political networks, while also shifting the salient semiotic register in media production from language to script in a younger generation of Santali-speaking readers, writers, and editors in the region.

Scripts, states, and artefactual histories of Santali-language print media

The explosion of print media in both Europe and its colonies is often linked to the phenomenon of ‘print-capitalism’. According to Anderson, the capitalist mode of production gave rise to the drive to ‘produce’ news and information as a saleable commodity, and the commodification of print produced a ‘monoglot-reading public’.Footnote 8 which would consume the news and, in doing so, develop something akin to a national imaginary. Print-capitalism provided the ideological ground linking an individual to a state, while also positioning individuals within markets. Analytically, the study of print-capitalism and media markets more generally has often broken down along the producer/consumer binary.Footnote 9 In Anderson's model, the ‘cultural roots’ of nationalism lie within the process of consumption, by which monoglot publics, who are all engaged in the process of consuming single-language news within a given territory, begin to see themselves as a collective. In Robin Jeffrey's study of the explosion of Indian print media between 1970 and 2000 in multiple languages, he highlights how publics themselves are actually quite diverse, but the unity arises within the class of producers, most of whom, though they write and produce in different languages, are aligned with the ‘national elite’,Footnote 10 helping to localize national agendas through close alliances with the national and regional state as well as regional political parties, even as they market themselves as offering an independent and adversarial voice.

Recent studies of the media in South Asia have challenged the producer/consumer binaries implicit in Anderson and Jeffrey's analysis of ‘print capitalism’ by examining more closely the mediating role of technology and language. For instance, Mankekar ethnographically explores the way in which television in the early period of liberalization in India articulated a ‘discourse of consumerism’ that aligned with middle-class aspirations but also prompted a ‘reconfiguration’ of relations within viewing families along lines of gender and generation.Footnote 11 Rajagopal focuses on the media's contribution to the rise of Hindu fundamentalism in the 1990s, describing how assemblages of media technologies such as television and newspapers worked together to sustain and propagate political ideologies.Footnote 12 In his analysis, it is language, namely the distinction between Hindi- and English-language media assemblages, which cause a ‘split public’ within classes of both producers and consumers, with Hindi language news more attuned to the cultural and religious claims underpinning the movement, while English language news is reported primarily through a political or legal lens.

Continuing to underlie many of these analyses, however, is a model of mass media transmission grounded in capitalist social relations that constructs the media-artefact as a market commodity. Yet, the network of Santali-language media described here operates differently than the ‘mass’ media examples presented above in that they do not seek to expand their publics beyond a limited readership nor do they seek profit as a primary motive for media dissemination. In this way, rather than ‘print capitalism’, the situation is more akin to the ‘print communalism’, as described by Udupa in early twentieth-century Mysore, which ‘promoted horizontally more finite communities imbued with a definite political agenda’.Footnote 13 This non-capitalist proliferation of media, which incurred significant loss to producers and circulated among a limited class of consumers, was critical, Udupa suggests, to the growth of the non-Brahman movement in early Mysore. In a similar way, the ‘print communalism’ under which Santali-language media is produced and circulates also contributes to the formation of a politics of autonomy among Santali-speakers, although, unlike in Mysore, these politics are crucially mediated by printing technology and script-form, revealing internal differences between the way they are practised and understood between different generations.

Script, media, and the politics of indigeneity

The situation of indigenous-language media in multilingual settings reveals how patterns of circulation cannot be clearly divided along lines of producer and consumer, and how the dissemination of media artefacts may operate outside market relations. For instance, in her study of Buryat media production in Russia, Kathryn Graber shows that Buryat media emerged through a Soviet policy that encouraged minority-language media production, and that it has flourished, despite language loss and a marked consumer preference for Russian-language publications. Buryat readers view the media object itself not as an informational source, but as an ‘emblem of social personae’,Footnote 14 which circulate alongside commodified Russian-language news sources but serve differently valorized ends.

In indigenous communities in North America and Australia, print media has contributed to the creation of what has broadly been called ‘aboriginal public spheres’,Footnote 15 which have provided spaces in which diverse communities which have been marginalized through settler-colonialism come together to articulate notions of sovereignty, and influence social policy at regional and national levels of governance. Studies of indigenous print media in these settings have complicated the relationship between oral and written varieties of language, as most indigenous languages are not widely taught in schools or used in written form by many speakers. Studies of Adivasi media in India have also explored emergent literacies in print media and their relevance for political and cultural assertion.Footnote 16

However, while these studies focus on the question of language, literacy, and representation in the crafting of distinct indigenous publics, Santali media production in eastern India presents a more complex picture in which neither language nor a unified Santali-reading public can be seen as the primary site for the articulation of political and social identities. Rather, the material and visual nature of the media form, which displays multiple, heteroglossicFootnote 17 combinations of Indic scripts (such as Eastern Brahmi or Devanagari), Roman, and Ol-Chiki, constitute a contested notion of Santali language for writers and readers. The shifting organization of graphic repertoires, and their different semiotic associations with linguistic code, ethnicity, and territory,Footnote 18 map out networks of circulation not sustained by profit or mass publics, but by relations of authority between people, classes, and generations in local Santali-speaking areas.Footnote 19 Ethnographic attention towards the graphic organization of text-artefacts in concert with their circulation and uptake reveal how networks remain durable despite divergent political and social orientations among differently positioned participants within local Santali-speaking communities along social vectors such as caste, class, and generation.

Missionary intervention and the origins of Santali-language media

The history of the origins of Santali-language magazine publication in the late colonial period highlights the relation between print artefacts, patterns of hospitality and exchange, and the spreading of institutional networks. As early as 1834, the United States-based Baptist Missionary Society, under the leadership of R. Lesley, sent mission delegations to work in Santal villages in the erstwhile Bengal presidency.Footnote 20 One of the missionaries, Jeremiah Phillips, became interested in Santal language and published a chapbook of Santali folk songs as well as a grammar of the Santali language in a modified Eastern Brahmi (Bangla) script.Footnote 21 These works are considered the earliest print publications in Santali.

However, the most significant contribution to Santali-language printing was made by Lars Olsen Skrefsrud, a Norwegian, who, after a spell in prison, left for India to become a missionary in 1863. It was there that he, and a Danish missionary named Hans Peter Borrenson, discovered the Baptists’ work among the Santals and decided to start their own mission in 1868 at Benagaria, a small village in what is now Dumka district, Jharkhand.Footnote 22 Borrenson and Skrefsrud rejected the dominant missionary practice at the time that sought to associate new converts with extant mission communities in Europe or North America, and aspired to create an ‘independent, indigenous Indian Home Mission to the Santals’,Footnote 23 in which the goal was to create an autonomous, Santal-run, and Santal-dominated church, not tied to any particular Christian community.

Early on, Skrefsrud believed that promoting an independent Santali language and script would instil a sense of autonomy among Santals that would allow them to conceive of themselves as linguistically and culturally distinct from neighbouring caste-Hindus, thereby rendering them more open to conversion.Footnote

24

He opted for the Roman scriptFootnote

25

over Eastern Brahmi, arguing that it better represented Santali sounds while also providing a distinct orthographic identity. In 1873, Skrefsrud wrote the first Santali-language grammar using the Roman script,Footnote

26

and in 1874, he spearheaded the establishment of the first Santali-language/Roman script printing press at the Benagaria Mission. The first book, a book of Christian songs called Benaga

![]() ia Seren' Puthi

Footnote

27

(The Benagaria Song Book), was printed in 1876,Footnote

28

and in 1887, the press published the Hodkoren Mare Hapdam ko reyak' Katha (The Stories of the Santal Ancestors), a compendium of traditional stories that Skrefsrud had collected from Kolean Guru, a learned Santal elder. The press would go on to publish not only mission-related material, but also books related to non-Christian Santali cultural practices.Footnote

29

ia Seren' Puthi

Footnote

27

(The Benagaria Song Book), was printed in 1876,Footnote

28

and in 1887, the press published the Hodkoren Mare Hapdam ko reyak' Katha (The Stories of the Santal Ancestors), a compendium of traditional stories that Skrefsrud had collected from Kolean Guru, a learned Santal elder. The press would go on to publish not only mission-related material, but also books related to non-Christian Santali cultural practices.Footnote

29

In 1890, Skrefsrud began publication of a Santali magazine, Ho

![]() Hopon ren Pe

Hopon ren Pe

![]() a (Santal ‘Guest’), in the Roman script.Footnote

30

The magazine was written ‘in the Evangelical idiom, for those educated at Mission schools, in an elaborate language’,Footnote

31

and contained articles on subjects from Greek antiquity to the Norwegian revival and Mughal empire.Footnote

32

The magazine also allowed the mission to expand its following in villages as far away as North Bengal and Assam, and frequently published letters from readers in different mission settlements. Distinct from other missionary publications at the time, which focused on general cultural debate and were read by mostly elite converts, ‘The Ho

a (Santal ‘Guest’), in the Roman script.Footnote

30

The magazine was written ‘in the Evangelical idiom, for those educated at Mission schools, in an elaborate language’,Footnote

31

and contained articles on subjects from Greek antiquity to the Norwegian revival and Mughal empire.Footnote

32

The magazine also allowed the mission to expand its following in villages as far away as North Bengal and Assam, and frequently published letters from readers in different mission settlements. Distinct from other missionary publications at the time, which focused on general cultural debate and were read by mostly elite converts, ‘The Ho

![]() Pe

Pe

![]() a,’ as Carrin and Tambs-Lyche write, ‘was altogether more evangelical and its readership more popular; it spoke directly to the converts.’Footnote

33

a,’ as Carrin and Tambs-Lyche write, ‘was altogether more evangelical and its readership more popular; it spoke directly to the converts.’Footnote

33

In addition to serving as a forum for debate, the magazine circulated with mission delegations as they moved back and forth from different Christian settlements throughout the area. On 17 August 1900, H. M. Borreson sent a letter to Baidyanat, a Santal who was leading a group of Christians in Dinajpur, in what is now the border area between West Bengal and Bangladesh:

Gel turui maha tayom-re marang kulhi du

![]() up nonde hoyok'talea, more ho

up nonde hoyok'talea, more ho

![]() iṅ kolkoa handaṅ kob galmaraoako. . .[nuko] dhorom puthiko idi toraoma ar em ńama. . .noa songete tinudi ‘Ho

iṅ kolkoa handaṅ kob galmaraoako. . .[nuko] dhorom puthiko idi toraoma ar em ńama. . .noa songete tinudi ‘Ho

![]() Hopon-ren Pe

Hopon-ren Pe

![]() a Sakam iń kolam kana jemon ape ondem boehape paḍhao joḍi. . .

a Sakam iń kolam kana jemon ape ondem boehape paḍhao joḍi. . .

In the next 16 days we will have a large meeting here, I will send five people over there to talk with [you all] over there [about what happened]. They will bring you some religious books and together I will also send the Ho

![]() Hopon-ren Pe

Hopon-ren Pe

![]() a magazine to you [sg] over there so that you [pl] [our] brothers may read it [translation by author].Footnote

34

a magazine to you [sg] over there so that you [pl] [our] brothers may read it [translation by author].Footnote

34

The letter implies that, like the distribution of religious texts, the magazine was also distributed by visiting mission contingents as a gift, similar to those one would bring when visiting one's friends or relatives in different villages. This relationship is evoked through the magazine's name itself: pe

![]() a in Santali translates as ‘guest’, but also implies a much deeper relationship to those settled and distant places and a set of specific social practices for honouring that relationship, often associated with rạska (communal joy). The magazine, typified as a pe

a in Santali translates as ‘guest’, but also implies a much deeper relationship to those settled and distant places and a set of specific social practices for honouring that relationship, often associated with rạska (communal joy). The magazine, typified as a pe

![]() a (guest), was thus taken up in larger networks of the circulation of people and exchange that characterized dispersed institutions such as the Santal mission.

a (guest), was thus taken up in larger networks of the circulation of people and exchange that characterized dispersed institutions such as the Santal mission.

In 1922, Ho

![]() Hopon-ren Pe

Hopon-ren Pe

![]() a was renamed Pe

a was renamed Pe

![]() a Ho

a Ho

![]() and is still published to this day. Other missions followed the success of Ho

and is still published to this day. Other missions followed the success of Ho

![]() Hopon-ren Pe

Hopon-ren Pe

![]() a, such as the Catholic Church, which began publishing a magazine along similar lines named Marsal Tabon (‘Our [inc]Footnote

35

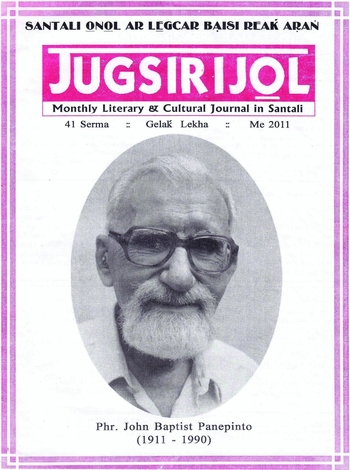

light’) in 1946. All of these magazines contained church-related information as well as poems, essays, stories, and dramas. They were all published in the modified Roman script developed by Skrefsrud and Bodding. These magazines, which contained religious and literary content, underscored the differences, both linguistic and orthographic, between Santali and neighbouring upper caste-Hindus, in the hope of fostering a sense of autonomy. The tradition of these magazines continues in the numerous contemporary Roman-script publications such as Jugsirijol, published from Calcutta since 1972, which highlights the missionary contribution to the Santali language through Roman-script publication. An example is this special issue devoted to Father John Baptist Paneptino, an American Jesuit missionary and editor of Marsal Tabon from 1956–1990 (see Figure 1).

a, such as the Catholic Church, which began publishing a magazine along similar lines named Marsal Tabon (‘Our [inc]Footnote

35

light’) in 1946. All of these magazines contained church-related information as well as poems, essays, stories, and dramas. They were all published in the modified Roman script developed by Skrefsrud and Bodding. These magazines, which contained religious and literary content, underscored the differences, both linguistic and orthographic, between Santali and neighbouring upper caste-Hindus, in the hope of fostering a sense of autonomy. The tradition of these magazines continues in the numerous contemporary Roman-script publications such as Jugsirijol, published from Calcutta since 1972, which highlights the missionary contribution to the Santali language through Roman-script publication. An example is this special issue devoted to Father John Baptist Paneptino, an American Jesuit missionary and editor of Marsal Tabon from 1956–1990 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The cover of Jugsirijol, May 2011 issue, celebrating the life of Father John Baptist Paneptino, published by the Santal Literary and Cultural Society, Kolkata. The magazine is edited by Dilip Hembrom.

The Roman script, however, was not universally accepted among Santals. In 1871, ‘Kherwar’, a strong movement founded by Bhagirath Majhi, a Santal religious leader, arose in the Santal Parganas and Jharkhand. The movement opposed both the British and caste-Hindu presence in the Santal Pargana region but also the Christian missionary presence, drawing condemnation from Skrefsrud and others missionaries.Footnote 36 Participants in this movement also, to a lesser extent, embraced printing, though they rejected Roman script, preferring the Eastern Brahmi script to write Santali. For instance, the first non-missionary printed work in Santali was Ramdas Tudu's Kherwar Bonghso Dhorom Puthi (Religious Book of the Kherwars) published in 1893.Footnote 37 The use of Brahmi scripts and the later development of independent scripts such as Ol-Chiki draw, in large part, on the legacy of the Kherwar movement. However, the movement, in particular its stances toward language and its articulation of Santal autonomy, was deeply influenced by the missionariesFootnote 38 and this shared legacy contributed to the subsequent struggle for Jharkhand.

Indian independence, federalism, and state language policy

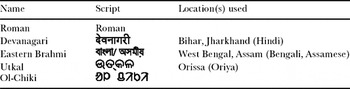

Following Indian independence, the 1956 States Reorganization Committee organized Indian federal states along linguistic and script lines, such that each federal state adopted an official language and script for state business.Footnote 39 The states of the erstwhile Bengal Presidency, for instance, were divided into Bihar, which adopted Hindi in the Devanagari script; West Bengal, for which Bengal in the Eastern Brahmi script was made the official script-language; and Orissa, which promoted Oriya in the Utkal script. Santals were dispersed across the borders of these linguistic-administrative regions and received education in the scripts and languages of their respective states. As a consequence, Santals began writing and modifying the respective Indian scripts of the states where they resided in order to write Santali (see Table 1).Footnote 40

Table 1. Scripts used for writing Santali and locations within India.

While Santali was not taught in schools, nor made an ‘official’ language of any of these states, state governments made an attempt to incorporate its minority populations into its polity through the publication and dissemination of Santali-language magazines in the respective scripts of the individual state.Footnote

41

For instance, in 1947, the Bihar government started a Santali-language magazine, Ho

![]() Sombad (Santal News). The publication aimed to promote literary production in Santali while also providing an interface between an emerging Santal elite, including the literate, landed class and salaried employees, and the state. Since Hindi in Devanagari script had been proclaimed the official script-language of a multilingual Bihar, Ho

Sombad (Santal News). The publication aimed to promote literary production in Santali while also providing an interface between an emerging Santal elite, including the literate, landed class and salaried employees, and the state. Since Hindi in Devanagari script had been proclaimed the official script-language of a multilingual Bihar, Ho

![]() Sombad was published in a slightly modified Devanagari script.Footnote

42

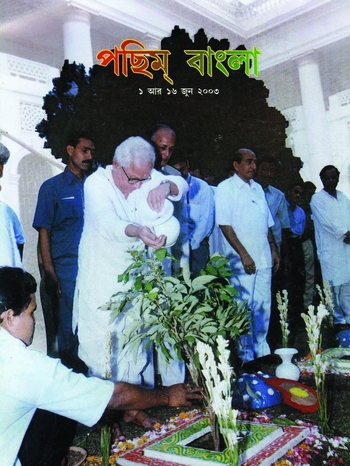

The choice of script and the state-sponsored nature of the publication made it such that its primary circulation was within the state of Bihar, although writers in Purulia district, West Bengal, also published in and read the magazine. In 1956, the West Bengal state government began publishing a similar Santali-language magazine, Galmarao (Discussion) in Eastern Brahmi script (Bengali), later to be renamed simply Pachim Bangla (West Bengal) (see Figure 2).Footnote

43

In both of these cases, the goal was to draw newly literate Santals and burgeoning Santali writers into the state sphere through participation in the magazine's production, while also disseminating Santali-language material in state scripts in the rural areas.

Sombad was published in a slightly modified Devanagari script.Footnote

42

The choice of script and the state-sponsored nature of the publication made it such that its primary circulation was within the state of Bihar, although writers in Purulia district, West Bengal, also published in and read the magazine. In 1956, the West Bengal state government began publishing a similar Santali-language magazine, Galmarao (Discussion) in Eastern Brahmi script (Bengali), later to be renamed simply Pachim Bangla (West Bengal) (see Figure 2).Footnote

43

In both of these cases, the goal was to draw newly literate Santals and burgeoning Santali writers into the state sphere through participation in the magazine's production, while also disseminating Santali-language material in state scripts in the rural areas.

Figure 2. Pachim Bangla magazine, this copy featuring the chief minister of West Bengal state, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, performing a Santal ritual. Published by the West Bengal Backward Classes Welfare Department.

In addition to the magazines sponsored by state governments, beginning from the late 1950s, the movement for Jharkhand and the assertion of a distinct domain of Santal literacy resulted in the formation of numerous small-scale organizations based in rural areas. These organizations, financed by wealthier patrons, enabled Santali writers to gain prestige and create a local network of literary, linguistic, and politically inclined people throughout different groups of villages. These magazines operated in a similar manner to the ‘little magazine’, small-scale and alternative Bengali-language publications that proliferated both in metropolitan centres such as Calcutta, as well as in district towns throughout West Bengal and neighbouring states with large Bengali-reading populations.

As Nag notes in her study of Calcutta-based little magazines, these publications were ‘never started with an eye towards business’ but ‘readership’ instead is ‘solicited among intellectual acquaintances and sought to be extended with the help of specific intellectual allies who at least share their political agenda in principle’.Footnote 44 These magazines rarely make any money and are often distributed for free.Footnote 45 They are also characterized by irregular circulation, in which magazines are often discontinued and new ones started, depending on the shifting alliances of members of the collective and availability of sources of funding. Thus, magazines allowed local organizations to cohere around certain principles, while fractallyFootnote 46 conferring prestige upon individuals involved in their creation and dissemination.

Little magazines had flourished in West Bengal since Independence. The rise of the Communist Party and the spread of Left politics further increased the number of Bengali-language little magazines published in West Bengal's rural districts. However, Santals responded to the spread of Bengali metropolitan culture by creating their own institutions, which mirrored those of their Bengali counterparts, yet were also positioned as autonomous from them.Footnote 47 Thus, even though Santali was not taught in schools, and hardly had any infrastructure for literary publication, Santali-language little magazines proliferated in the Santali-speaking area. For instance, as one magazine editor told me with great pride, during the 1970s in the rural areas of Purulia district, West Bengal, there were around 22 Bengali little magazines in circulation and more than 16 little magazines in Santali. This was quite a feat considering the lack of printed Santali literature and the absence of formal education in the language. These little magazines were sustained by an elite of wealthy patrons and educated Santals as well as by the expanding networks of Santali-language literacy in which oral performance practices also played a crucial role.Footnote 48

Like the Bengali magazines Nag discusses, Santali little magazines were often discontinued, depending on the formation and breakdown of different readership networks. If members of the group found salaried employment or other sources of income, some continued, but often groups split and the number of magazines proliferated. However, in all my conversations with editors, they told me that in their experience, magazines were never able to turn a profit. Yet their publication and distribution, which often consisted of gifting between editors or members of different organizations, allowed for the formation and continuation of local political networks. Consequently, it is no surprise that some of the most active members of contemporary Jharkhand political groups, or other indigenous political formations, were, or had been, magazine editors, contributors, or distributors.

The Jharkhand movement and the creation of Ol-Chiki script

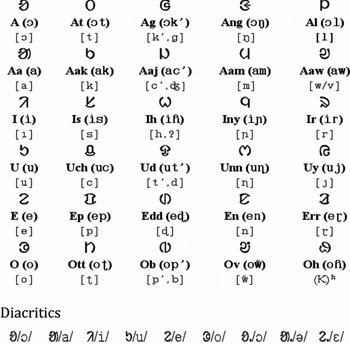

In 1938, a decade before Indian independence, Jaipal Singh, the leader of the Adivasi Mahasabha,Footnote 49 led a charge to create an independent state of Jharkhand, including the Santali majority blocks of southeast West Bengal, southern Bihar, and northern Orissa.Footnote 50 At the same time, political consciousness emerged among different tribal communities in the Jharkhand region and a number of independent scripts were created for tribal languages. Scripts for diverse Austro-Asiatic languages such as Sora and Ho were developed during this time,Footnote 51 though none circulated as widely as the Ol-Chiki (‘Writing symbol’) script developed for Santali by Raghunath Murmu, a primary schoolteacher in the princely state of Mayurbhanj, Orissa.Footnote 52 The original characters were said to have been revealed to Murmu in a dream by the Santal spirits or bongas as early as 1925, but it was only in the 1930s that Murmu, under the patronage of the royal family of Mayurbhanj, developed printing blocks and a hand press for the script, which he displayed in the 1939 Mayurbhanj State exhibition.Footnote 53 Murmu argued that the new script could better account for Santal phonology, especially the glottalized ‘checked consonants’ and reduced vowels,Footnote 54 than either the missionary-derived Roman script, or existing Brahmi scripts such as Devanagari or Eastern Brahmi. Unlike existing Indic scripts (and like the Roman script) Ol-Chiki was alphabetic, with vowels and consonants represented independently. The script was also in part pictographic: each letter also had a word and image associated with it. For instance, the Ol-Chiki letter for ‘a'a is called lo (‘fire, flame’) and is supposed to depict a flame. The letter for ‘l'l is ol ‘writing’ and represents a hand holding a pen.

Figure 3. Ol-Chiki script. Source: http://wesanthals.tripod.com/id45.html; used with permission.

The period immediately following Indian independence was a tumultuous one in the Adivasi regions of eastern India. The demand for Jharkhand was rejected, and uprisings among Santals and other Adivasis to join their regions to Bihar and, eventually, a future Jharkhand, were violently suppressed. For instance, in 1949 in Murmu's own state of Mayurbhanj, Santals led by Sonaram Soren organized an uprising demanding that the erstwhile princely state be included in Bihar instead of Orissa. The uprising was violently suppressed by the Indian Army.Footnote 55 In 1956, under the Chota Nagpur Tenancy Act, the large tribal plurality district of Manbhum was partitioned between Bihar and West Bengal, resulting in the loss of land tenure rights for Adivasis living on the Bengal side (in the district now known as Purulia).Footnote 56 Organizations formed around Jharkhand and a politics informed by an ideology of tribal autonomy, born from a sense of loss and struggle, remained strong throughout the border regions of Orissa, Bihar, and West Bengal.

Consequently, new networks emerged, in part through the circulation of artefacts mediated by three ideological elements: language, culture, and script. Drawing on the equation between language and an independent Santal nationality constructed in the nineteenth century through missionary activity, Jharkhandi political organizations reiterated a commitment to language as a way of uniting Santali-speakers across a diverse geographic region. Parallel to the concern with language was a concern with script. As the Santali-speaking area had been split across linguistic and graphic lines, the Santali language was written in numerous scripts, such as Utkal, Devanagari, and Eastern Brahmi. Many Jharkhand activists believed that the use of diverse scripts, supported in part by state administrations, iconized division among the Santali-speaking community and continued to undercut claims for Jharkhand. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Murmu started touring the Santali-speaking area and offered the Ol-Chiki script as a way of unifying Santals across graphic boundaries and laying the graphic and linguistic foundations for a future Jharkhand state. Murmu's message became especially popular among Santali-speaking migrants in the newly established steel factory town of Jamshedpur, and they supported the establishment of a press and the subsequent publication of Ol-Chiki primers and an Ol-Chiki magazine.Footnote 57 In 1964, Murmu established an organization called the Adivasi Socio-Educational Cultural Organization (ASECA),Footnote 58 to help circulate the script in the border regions of West Bengal, Jharkhand, and Orissa. The organization also coordinated Ol-Chiki literacy classes in villages, and popularized the script through the staging of popular dramas and songs that extolled the script's power to unite Santals across the country and its connection to Santal spirits, rituals, and histories.Footnote 59

Murmu's vision, which fuelled the patronage and enthusiasm for Ol-Chiki script, was that Santals throughout the Santali-speaking areas would cease to use regional scripts and adopt Ol-Chiki, uniting Santali-speaking communities even in the absence of the Jharkhand state.Footnote 60 However, as regional-language literacy was entrenched by this point, the complete replacement of Brahmi scripts with Ol-Chiki would have been impossible to realize. Nevertheless the spread of Ol-Chiki added yet another distinctly politicized layer within the multigraphic milieu.

Local media networks: authority, class, and generation in Purulia, West Bengal

In this section, I focus on the ways in which the production, circulation, and exchange of Santali magazines created local political networks in the southern region of Purulia district, West Bengal. As opposed to more long-standing forms of Santali social organization, such as the majhi-pargana system, or structure of traditional village council governance, I trace how conceptions of language and culture embedded in the production of media artefacts empowered new forms of political organization among a literate Santal elite, sustaining a politics of autonomy in local settings even as incorporation into Bihar, or later Jharkhand, become an impossibility. I explore how printing technology and the spread of the Ol-Chiki script transformed these networks across different generations of editors, writers, and readers, producing new ideas of what constitutes a properly ‘Santali’ media artefact, in which social and political distinctions are made on graphic rather than on purely linguistic criteria. In the last part of this section, I touch on ways in which the state of West Bengal has attempted to assimilate Santals through intervention in the media field.

Magazines, or what readers and editors explicitly term (using the English) ‘literary and cultural journals’, are often started by voluntary associations led by members who have a steady, salaried income. These associations, usually referred to in Santali as bạisi ‘groups’, gaonta ‘organizations’, or in the Bengali, sabha ‘meeting-groups’, are organized in the name of promoting Santali literature, culture, and language. However, they also simultaneously serve as networks through which Jharkhandi politics, Santali-language literacy, and the politics of autonomy are cultivated. The formation of these associations functions as a way of obtaining prestige within Santali communities that institutional or economic privilege alone do not guarantee. Central to this economy of prestige are exchange relationships, and one of the most prominent artefacts that mediate these relationships is the printed journal. Hence, editors and association members print and publish magazines at significant cost to themselves. Copies of the magazines are frequently offered for free or at a very nominal price, such that it is impossible for publishers to completely recover costs. The magazines circulate primarily through a multi-tiered distribution chain in which editors give copies to associated members (some of whom are also editors of their own journals) who then distribute them to people they know.

Consequently, the publication and dissemination of magazines, like the Bengali little magazines Nag discusses or the print publications in Mysore described by Udupa, have very little to do with economic profit. They serve, on the one hand, to unite members of these groups, all of whom share particular commitments stemming from allegiance to certain localities and political positions, and, on the other, they also connect these groups to larger ideological networks where notions of Santal ‘literature and culture’ are mediated through script-choice and institutional arrangements at varying scales beyond particular localities or regions.

In these scenarios, organizations are started by local elites, often schoolteachers, who then try to cultivate first and foremost a Santali literary class through regular meetings and the production and dissemination of literary and cultural journals. Although organizations begin with one or two journals, numbers tend to proliferate with succeeding generations, although publication and distribution remain sporadic. This can be seen for instance in the Bandowan block, southern Purulia district, West Bengal, where I conducted fieldwork from 2009–2011. Bandowan is a plurality Scheduled Tribe area, the majority of whose people identify as Santals, but it is also home to populations of Munda and Kheria, as well as several Hindu castes, and a small Muslim community. Bandowan, like much of southern Purulia, is a forested area with no major town or railhead, and very few resources, but which nevertheless has a strong history of social organization among Santali communities.

The language movement and Santali media production in Purulia district, West Bengal

In 1976, the famous Santali poet, Sarada Prasad Kisku, a local primary schoolteacher based in Bandowan block, helped start Susạ

![]() Gaonta (Social Welfare Club), a social welfare organization that was influential on multiple generations of writers and editors in the region. As part of the club's activities, Bhabot Soren and Sarada Prasad Kisku edited a magazine called Susạ

Gaonta (Social Welfare Club), a social welfare organization that was influential on multiple generations of writers and editors in the region. As part of the club's activities, Bhabot Soren and Sarada Prasad Kisku edited a magazine called Susạ

![]() Ḍahar [Road to Social Development], in Eastern Brahmi script that featured the work of many writers in the area. At the same time, the club and mentor figures such as Kisku also helped younger writers and editors begin their own projects. In 1976, Mahadeb Hansda, at that time a young schoolteacher from a small village in Bandowan block, with the help of Sarada Prasad Kisku, started Tetre [Marriage Anointer] magazine. It became very influential in the area among writers, editors, and others, ran until 1993, closed down, and then restarted again in 2010. Another Kisku acolyte, Kolendrath Mandi, also from a village near Bandowan, began Sili [Hair-rope] magazine in 1981, which has been running continuously to date. These magazines are distributed through networks that had already been established through organizations such as Susạ

Ḍahar [Road to Social Development], in Eastern Brahmi script that featured the work of many writers in the area. At the same time, the club and mentor figures such as Kisku also helped younger writers and editors begin their own projects. In 1976, Mahadeb Hansda, at that time a young schoolteacher from a small village in Bandowan block, with the help of Sarada Prasad Kisku, started Tetre [Marriage Anointer] magazine. It became very influential in the area among writers, editors, and others, ran until 1993, closed down, and then restarted again in 2010. Another Kisku acolyte, Kolendrath Mandi, also from a village near Bandowan, began Sili [Hair-rope] magazine in 1981, which has been running continuously to date. These magazines are distributed through networks that had already been established through organizations such as Susạ

![]() Gaonta, and the now numerous clubs and organizations that have started in Santal-majority villages in the area.

Gaonta, and the now numerous clubs and organizations that have started in Santal-majority villages in the area.

For instance, Tetre is distributed through a large network of association members throughout West Bengal, but most of these members have connections to the Purulia literary scene, either through residence or kinship. Local bazaars also carry copies of the magazines, which are physically brought to stores by editors or Tetre associates. In the village where I stayed during my field research, located some 16 kilometres from Bandowan town in Bankura district, West Bengal, I saw more copies of Tetre and Sili circulating than any other Santali-language magazine. The editors of the magazines were also well known in the village, as they appeared in cultural programmes and local fairs to distribute and promote their magazines, or to speak on issues relating to language, literature, and community. The magazines’ circulation and reception act in concert with other domains of Santali literacy, where articles or plays published in these magazines are performed in drama competitions that occur during village festivals. For example, during a drama competition the Tetre editor told me how certain dramas performed during the competition had been first published and circulated in Tetre, but now had become thoroughly recontextualized as standard Santali-language drama performances performed by local drama groups.Footnote 61

However, in the case of Purulia-district publications one can track certain divergent orientations toward what constitutes a ‘literary and cultural journal’ in different generations of editors. This is illustrated by the ways in which editors choose to organize multiple scripts on the journals’ covers and to represent content. Earlier magazines such as Tetre were written solely in the Eastern Brahmi script. Even today, unlike most literary and cultural journals the title page of Tetre continues to be only in Eastern Brahmi (see Figure 4), with no English-Roman. As Santali was not institutionally taught, and the Jharkhand movements and a concomitant Santali literary domain emerged in Purulia independently of the rise of Ol-Chiki, the Eastern Brahmi script was the medium of literary expression. In addition, Santals did not own independent presses, and handwritten documents were collected from villages and brought into nearby towns, where the only typesetting available was in Eastern Brahmi.

Figure 4. Cover page of Tetre magazine, edited by Mahadeb Hansda, Kaira, Purulia, West Bengal.

Sili, on the other hand, is much more typical of most literary and cultural journals published in West Bengal today. While, like Tetre, the content is all in Santali/Eastern Brahmi, the title page (see Figure 5) includes three scripts: Ol-Chiki, Eastern Brahmi, and Roman. This script combination, which is also prevalent in Santali newspapers,Footnote 62 delineates a formal domain of Santali media that in West Bengal is constituted through the interaction between these different scripts. However, the editor of Sili told me that Ol-Chiki was added to the cover page in the 1990s in response to mounting political pressure by the readership and ASECA activists, who threatened to boycott the journal if Ol-Chiki did not feature prominently on the cover page (although there was no apparent demand to change the script of the content inside). Even with the prominent placement of Ol-Chiki on journal covers, the editors of Sili and Tetre, as well as many writers of their generation, persist in using Eastern Brahmi for the main content, claiming that in Purulia, literary and cultural organization is primarily about language and not about script. For these editors this claim, in addition to the fact that many of the writers, committee members, and readership are unfamiliar with Ol-Chiki script, justifies the continued use of Eastern Brahmi in these magazines.

Figure 5. Cover page of Sili magazine, edited by Kolendranath Hansda, Shirishgoda, Purulia, West Bengal.

From language to script: shifting forms in contemporary print media

Contrary to the claim that the literary movement in Purulia is primarily about language and not about script, younger editors hailing from Purulia district who have been introduced to Santali writing and editing through the very same local networks, have chosen to publish their magazines almost exclusively in Ol-Chiki script. One reason for this is that, following Raghunath Murmu's visit to West Bengal in 1979, and the expansion of the ‘Santali Bhasha Morcha’, which sought to popularize Ol-Chiki in West Bengal, script became a major semiotic form around which questions of linguistic rights, recognition, and ideologies of tribal unity across linguistically defined regions were articulated. At the same time, in rural areas the use of computers and digital technology increased during this period, and Ol-Chiki fonts adapted for Unicode quickly spread to Santali-speaking areas such as Purulia. As Santals became more proficient in Ol-Chiki typing—which is generally easy to learn since it follows Roman quite closely—and typesetting made the transition from manual printing to digital off-set printing, entire Ol-Chiki documents could be printed easily and at relatively low cost.

Consequently, for an older generation of editors who grew up in an era of manual typesetting, the issue of script was moot, as their efforts were primarily directed towards promoting a then non-recognized linguistic code as a literary and political register, perpetuating the project of Santali-language literacy started by people such as Sarada Prasad Kisku. A younger generation, however, started publishing magazines from the 1990s onwards, during the rise of a post-Jharkhand politics, at a time when statehood was no longer an option and instead of a state, unity was imagined and expressed through circulating forms such as Ol-Chiki.Footnote 63 For them script form rather than linguistic code became inextricably intertwined with the politics of autonomy. This ideology subsequently impacted on the organization of the literary and cultural journal genre for a new generation of editors who were mentored through these local networks.

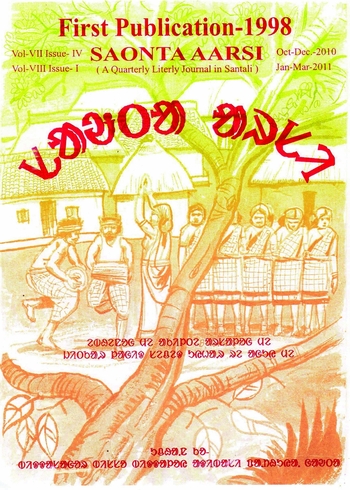

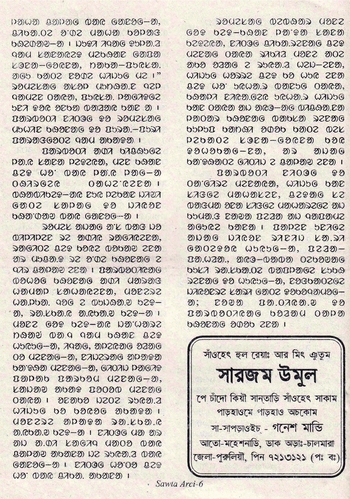

For instance, one of the first magazines of the newest generation, Saonta Arsi (Society's Mirror), started in 1990 by younger editors who grew up in villages in Purulia district with a strong history of literary organization, is published primarily in Ol-Chiki script.Footnote 64 The title page, shown in Figure 6 below, features information in Roman script-Santali, English, and Ol-Chiki, which is a common constellation found in a variety of Ol-Chiki materials, from signboards, movie posters, and publicity posters.Footnote 65 Inside the magazine, all of the literary content is in Ol-Chiki; however, the advertisements within the magazine are mostly in Eastern Brahmi, even if the product is for other Ol-Chiki material, like an advertisement for another Purulia-based magazine, Sarjom Umul (Shadow of the Sal Tree) (see Figure 7, bottom right-hand corner), published by younger editors. This suggests that the advertisements are trying to reach a broader, more multi-generational audience than the text of the journal itself.

Figure 6. The title page of Saonta Arsi, edited by Pradib Hembrom and Dijapada Hansda, Vidyasagar University, Pạthuạ Gaonta, Paschim Mednipur, West Bengal.

Figure 7. A page from inside Saonta Arsi, featuring Ol-Chiki content and Eastern Brahmi advertisements.

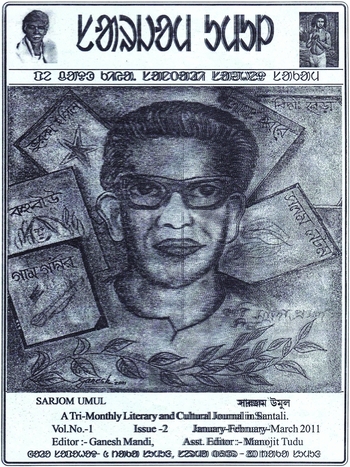

Sarjom Umul, referred to above, is more recent than Saonta Arsi, and started in 2010. When I met one of the editors, an English-language high schoolteacher in Purulia district, only two issues had been published. This magazine also is in Ol-Chiki script, and the editor mentioned to me that he, like many of his peers, believes that the use of a single script, Ol-Chiki, is necessary in order to unite Santals. However, as the cover of the second issue suggests, the editor and the Sarjom Umul committee have also been influenced and shaped by the local literary movement that took place in Purulia district. As Figure 8 shows, the title page features an Ol-Chiki banner along with pictures (on the top left) of Raghunath Murmu, the founder of Ol-Chiki, and (on the top right), Sidhu Murmu, the leader of the Santal Hul, linking historical experiences around Santali autonomy and insurrection with the present-day movement for Ol-Chiki script. Yet the magazine cover art features Sarada Prasad Kisku, the poet from southern Purulia district, who is the most influential person within this local, Purulia-based network. All of his works, with their titles notably displayed in Eastern Brahmi script, are featured in the background. One of the editors is also a committee member of Tetre magazine; I met him at Mahadeb Hansda's house where he had arrived to pick up copies and distribute them. Inside the magazine (see Figure 9), there are also advertisements for other locally produced journals, such as Tetre, Sili, and Saonta Arsi, with their titles in Eastern Brahmi script, illustrating the network of locally produced text artefacts in which this journal is enmeshed, one that was still marked by the use of Eastern Brahmi. I received the magazine at the house of Hansda, where the editor had come to pick up copies of Tetre and ask questions of the editor and a senior local writer. In greeting them (and me), after performing the ritual Johar greeting, he gifted all of us copies of his magazines, a practice I witnessed frequently among editors and publishers.

Figure 8. The title page of Sarjom Umul, edited by Ganesh Mandi and Manojit Tudu, Maheshnadi, Purulia, West Bengal.

Figure 9. The inside of Sarjom Umul, with content in Ol-Chiki but advertisements in Eastern Brahmi script.

Charting the history of the literary and cultural journal in one small part of West Bengal, I have shown how, even within the same networks and regions of circulation, the form of the literary and cultural journal differs between generations. The literary movement started in the area in concert with demands for both Jharkhand and a separate domain of Santali literacy at a time when literacy was associated with dominant Indo-European languages. Text artefacts in Santali mediated those goals, and through practices of production and exchange, these artefacts were classified under the genre of the literary and cultural journal. Older generations, as I have explained above, created these magazines, written in Santali in the most accessible script, as a platform to promote Santali-language literacy. The magazines engendered new economies of prestige in which the financial investment by editors and their associates, as well as the labour involved in their publication, dissemination, and promotion at various community events, such as village festivals or state-sponsored functions, conferred authority among the community that could not be guaranteed by class position or educational attainment alone.

While the younger generation of editors was also subject to these economies of prestige, they take for granted the fact of Santali-language literacy. In addition, magazines are produced in a milieu where publishing a journal is no longer remarkable, and, if the editor is a schoolteacher or writer involved in political or literary organizing, often expected. The rise of digital technology and off-set printing and the ease with which Ol-Chiki can be printed without relying on a press has further increased the number of magazines produced in Santali. The emphasis has shifted from language to script in the discourse of younger editors, whereby, for them, script has now become the salient semiotic modality for expressing an autonomous literary and cultural domain for Santali. While Ol-Chiki magazines continue to have a lower circulation than Eastern Brahmi magazines, they are beginning to become widely available and are more enthusiastically embraced by younger readers. Indeed, with the recent introduction of Ol-Chiki and Santali in some rural high schools from class nine, and with Santali-language courses now available at select universities in West Bengal, an increasing number of the current generation of students are becoming proficient in Ol-Chiki script and embracing its ideology and, with that, both readership and publication in the script will continue to grow.

Media circulation, class, and the contested nature of authority

As discussed in the previous section, literary and cultural journals were a way through which certain networks between poets, authors, localities, and institutions crystallized. Script-code variations reveal how these networks are transformed, and also how particular genres are recontextualized, depending on the networks in which the artefacts circulate and the differential position (along certain vectors, such as generation) of those participating in those networks. The networks provide a way in which editors may then link concepts such as ‘culture’, ‘language’, and ‘script’ to disparate political registers, such as the language of recognition, the politics of autonomy, communal joy (raska), and the socialized difference that Santals express vis-à-vis Hindu and Muslim castes, creating an economy of prestige through which their education and class status may translate into authority within the community. In this way, the editors, who are elite in terms of economic standing and privilege relative to most other Adivasis in the area, use the production of magazines and their position within committees of interested authors, students, dramatists, song-dance performers, and so on to garner authority within their communities that their class status and salary does not automatically guarantee them.

Yet this authority is not uncritically accepted by those among whom the journals circulate. For instance, a close interlocutor and Jharkhand party leader would sometimes sit in my room flipping through magazines such as Tetre and Sili. He said he had respect for the editors, but when he looked at the lists of association members, he would comment derisively that many of them think that because they have salaried employment and are involved with publishing and disseminating magazines they gained respect and authority within the Santal community. On the contrary, he argued—in an opinion I heard from many Santals, including editors and publishers—the locus of traditional authority lay in the majhi-pargana (village headman) system. This comprises village headmen families and appointed advisers, many of whom have run village affairs for generations and who often have little or no schooling, relying solely on agriculture for their livelihoods.Footnote 66 Thus, my interlocutor claimed, magazine associations, which were made up of an educated new elite, in no way competed with that form of authority. At the same time, he (who was not related to a headman family) owed his authority in the community to his high position in the local Jharkhand Party faction.Footnote 67 Magazines, then, only serve to mediate a fragment of the many cross-cutting networks of authority within Santali-speaking communities, networks which include political parties and structures of village and community governance. However, as this conversation demonstrates, magazines constitute a visible semiotic artefact in which claims to authority circulate, allowing for these claims to be ideologically brought together or shorn apart for different local political projects.

State-sponsored Santali magazines in West Bengal

I have described multi-generational, locally grounded networks in which literary and cultural journals circulate and how through that circulation, the genre, along with ideas of language, become artifactualized. The last network I will mention is that of state-produced or state-supported magazines, that is, the ‘official’ Santali-language literary and cultural journals produced with patronage from the West Bengal state government. Although the state only produces one (or two) magazines, they are part of a network in which people are connected primarily through their status as citizens of a given administrative territory, rather than some other relationship—of kinship, hospitality, mentorship, or religious affiliation—thus providing a ripe terrain for contestation. From my conversations with an older generation of writers, the magazine Pachim Bangla, published by the Government of West Bengal Backward Classes Welfare Ministry in Calcutta, was influential in their exposure to literacy. Like journals today, it circulated on college campuses and school hostels, where copies would be passed around and read, exposing students to writing in Santali from throughout the state. It also gave people templates on how to write literature in Santali-Eastern Brahmi script.

Unlike other journals, Pachim Bangla maintained, even until the early 2000s, an insistence on the strict use of Eastern Brahmi-Santali in both the title page and all content. Visual imagery on the title pages usually consisted of photographs of Santal villages, juxtaposing visions of development and traditional pastoral scenes or featuring people engaged in some kind of marked traditional activity, such as agriculture. Pachim Bangla, unlike the literary and cultural journals described above, did not have a history of being enmeshed either in local Jharkhandi politics (being a state-sponsored enterprise), yet, according to interviewees, it played an important role in the cultivation of a generation of writers in various parts of the state. However, by the time I conducted my fieldwork, the former editors said that the journal was effectively out of print due to the Ministry's neglect, and I was unable to find any recent copies. Old copies were, however, still available at village fairs and literary programmes, and I procured a number of magazines from the early 2000s, suggesting that they are still read, bought, and sold, regardless of their out-of-print status.

In 2007–2008, the Communist government in West Bengal organized a ‘Santali Academy’ along the lines of the already existing ‘Bangla Academy’. Thus, while the government's explicit aim was to institutionalize Santali along the lines of Bengali, many authors and editors I talked to suggested that it reflected the Communist government's attempt to marshal political support among Santal elites in light of growing political unrest in the Santali-speaking areas following Communist attempts at economic liberalization and privatization.Footnote 68 The Santali Academy attempted to bring together authors and editors embedded in different networks, including the leaders of ASECA, who militantly supported Ol-Chiki; Roman-script editors, who were often vehement supporters of it; and the vast network of authors who wrote and published in Eastern Brahmi and who had varying opinions on the question of script. The nascent Academy was fractured almost immediately along the lines of script, and the government, according to the participants I talked to, sided with Ol-Chiki advocates, causing some senior writers to resign. Others such as the late Dhirendranath Bhaskey also resigned for political reasons, particularly the government's handling of the Maoist insurgency in the Santal-dominated Lalgarh area, near his native village.Footnote 69

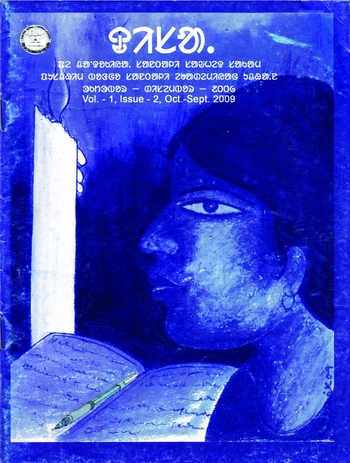

By attempting to incorporate or recognize Santali institutionally, the state government indirectly contributed to greater polarization around the question of script. Script not only became a medium through which different networks congealed or ruptured, but also a form around which people struggled for state resources, and the concurrent prestige that these resources brought. Whereas before, during the publication of Pachim Bangla, the magazine functioned similarly to the Soviet-sponsored Buryat-language newspapers examined by Graber (indeed, it was published for a while by the Ministry of Information) and disseminated a certain view of literature and culture to the tribal margins of the state, the emergence of the Santali Academy revealed the state's idea of a unified Santal citizen of West Bengal to be a fantasy. What emerged from the disputes and fractures was the state-sponsored publication, Disạ (Direction). Because these publications continued to be informed by a monoscriptural bias (inherent in an idea of a unified reading public), and the question of script itself broke down this monoscriptural formulation, Disạ had to be published simultaneously in two editions per issue, one in the Eastern Brahmi script (see Figure 10) and the other in Ol-Chiki (see Figure 11). The issues look exactly the same, with the same cover art and the same content. The only difference is that the Ol-Chiki cover includes slightly more information, letting us know that the magazine was published by the West Bengal Santali Academy. Though almost everyone who would read the publication is likely be familiar with the Eastern Brahmi script, the government has also allied itself with a political project that sees Ol-Chiki script as the single script for Santali.

Figure 10. Disa, in Eastern Brahmi script, Paschim Bangla Santali Academy, Kolkata, West Bengal.

Figure 11. Disa, in Ol-Chiki script, Paschim Bangla Santali Academy, Kolkata, West Bengal.

Consequently, the publication and dissemination of Disạ constitutes yet another semiotic network in which artefacts attain meaning through circulation. In this network, bureaucratic imaginaries of language planning (single-script Santali media), government attempts at incorporating its Santali-speaking minority within the ambit of state-sponsored cultural institutions, and the fractures around script coincide. Although Disạ’s editor was respected in the field of Santali-language print, the institution it represented—the Santali Academy—became, for many writers, an object of political struggle, often discussed as part of a political party apparatus. Factions supporting different scripts were said to be linked to different political parties, and the positions of the Santali Academy and the layout of the magazine itself were often considered to be a reflection of the agenda of the party in power (during most of my fieldwork, it was the Communist Party of India-Marxist).

Yet, even though the magazine was the source of so much contention, I rarely saw it circulated in the rural areas where I conducted my fieldwork. The only time I saw it was at local fairs, where I bought a number of back issues, both in Eastern Brahmi and in Ol-Chiki, that were on sale. I even did not see the magazine circulate much among the writers and editors I spoke to. This suggests that even though both the Academy (which was well-resourced) and the magazine were objects of much discursive contestation, its reach was actually quite limited. It appears therefore that by this time the local networks of Santali publishing, dissemination, and distribution had become so strong and robust in the Santali-speaking areas as to mitigate the impact of state intervention in this domain.

Conclusion

From the beginning of Santali printing, when Santali literary journals were disseminated along with religious texts and mission publications as part of travelling mission delegations, to the current situation where they are printed in multiple scripts throughout the Santali-speaking area, Santali-language magazines have served to promote regional political autonomy; spread and consolidate institutional networks; catalyse the formation and maintenance of local trans-generational organizations; and create an interface between local elites and the state. In this article, I have outlined a social history of these networks, tracking how the practices of exchange and technologies that constitute them relate to changing ideas of Adivasi politics through their use and the organization of script in particular. I argue that after the creation of the Jharkhand state, and the failure to include tribal majority areas in nearby states, a younger generation of Santali writers and editors in West Bengal has shifted the site of political assertion from language to script. This ideological transformation is rooted in the history of multigraphic Santali-language publications, as well as the politics of autonomy and contested nature of authority in local Santali-speaking communities.

On my return to southwest West Bengal in 2015, I witnessed a number of interesting developments that further complicates the field of Santali-language magazine publishing. For instance, in 2011, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) lost its first election in the state for 40 years, and the opposition Trinamool Congress government took over. However, rather than retrenching its policy around Ol-Chiki, the government recognized the popular support that the monographic ideology enjoyed among the younger generation of Santals, and accelerated the implementation of Santali-language, Ol-Chiki script education in schools and colleges, and discontinued the Eastern Brahmi edition of Disạ. On the other hand, in the villages, magazines that had pioneered Ol-Chiki-only Santali-language publication such as Saonta Arsi were shutting down. The editor of Saonta Arsi is now working on a new publication, Bhabna (Feeling), which is bilingual—Santali and Bengali—and digraphic—Ol-Chiki and Eastern Brahmi. By rejecting the use of Eastern Brahmi for Santali-language content, the magazine serves to perpetuate the monographic ideology, while simultaneously addressing the multilingual readership of the region more generally. Finally, magazines like Sarjom Umul, which are still being produced in an Ol-Chiki format, also started to create pages on digital platforms such as Facebook. These platforms were increasingly being used to reach out to younger readers who communicated primarily through mobile phones. These sites reiterated a commitment to Ol-Chiki, though users primarily employed a nonstandard Roman to write in Santali (since Ol-Chiki was not supported on these platforms). Far from retreating from print, the platforms served to create digital communities that reinforced the connection between cultural and political issues, print artefacts, and Ol-Chiki script.

While the situation of Santali-language media production is complex, it is by no means unique. Tribal and minority-language communities throughout IndiaFootnote 70 and other parts of AsiaFootnote 71 have continued to create new scripts, and new technologies have facilitated the production of minority-language media in ways not possible a generation ago. This case study points to the utility of examining graphic practices independent of linguistic code for the study of political assertion and print cultures in multigraphic regions such as South Asia. Understanding what the media ‘says’ beyond the magazines’ linguistic or discursive content requires a close analysis of their material and graphic form and the wider political and social networks in which they circulate. In doing so we may be better able to analyse the ways in which territory, community, and authority are multiply configured through processes of mediation.