Introduction

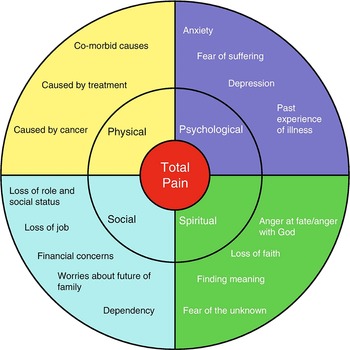

Most patients with a life-limiting illness experience multiple physical symptoms such as pain, fatigue, lack of appetite, and dyspnea (Zambroski et al. Reference Zambroski, Moser and Bhat2005; Teunissen et al. Reference Teunissen, Wesker and Kruitwagen2007; Moens et al. Reference Moens, Higginson and Harding2014). However, during clinical consultations, patients and clinicians mostly focus on one or few symptoms only (Homsi et al. Reference Homsi, Walsh and Rivera2006; Sikorskii et al. Reference Sikorskii, Wyatt and Tamkus2012). In addition to physical symptoms, patients often experience psychological, social, and spiritual problems, such as anxiety, financial concerns, and fear of the unknown (Bandeali et al. Reference Bandeali, des Ordons and Sinnarajah2020; Ullrich et al. Reference Ullrich, Schulz and Goldbach2021). In the conceptual framework for symptom management that is still widely accepted in the palliative care field (Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Pini and Edwards2022), a symptom is defined as a “subjective experience reflecting changes in a person’s biopsychosocial function, sensation, or cognition” (The University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing Symptom Management Faculty Group 1994; Dodd et al. Reference Dodd, Miaskowski and Paul2001). Patients’ experiences of symptoms are influenced by all 4 dimensions of palliative care, as illustrated in the total pain model first introduced by Cicely Saunders (Figure 1) (Saunders Reference Saunders1964; International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) 2009). The experience of pain is not only caused by “actual or potential tissue damage” (International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) 2020) but is also affected by psychological, social, and spiritual problems (Saunders Reference Saunders1964; International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) 2009). Vice versa, physical symptoms can cause or increase nonphysical problems, such as isolation, feelings of hopelessness, and fear of suffering (Krikorian et al. Reference Krikorian, Limonero and Román2014; Dong et al. Reference Dong, Butow and Tong2016). Since physical symptoms and nonphysical problems might mutually reinforce each other, both need to be considered to optimally alleviate symptom burden (Chen and Chang Reference Chen and Chang2004; Fitzgerald et al. Reference Fitzgerald, Lo and Li2015; Wang and Lin Reference Wang and Lin2016; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Liu and Li2019; Pérez-Cruz et al. Reference Pérez-Cruz, Langer and Carrasco2019).

Fig. 1. The total pain model (International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) 2009).

In this study, we defined multidimensional symptom management as the simultaneous assessment, treatment, and reassessment of multiple symptoms while considering physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects. Despite widespread consensus on its importance, the concept is difficult to integrate into daily practice, even in specialized palliative care settings like hospices (de Graaf et al. Reference de Graaf, van Klinken and Zweers2020). Care at the end of life is mostly provided by clinicians who do not have specialized palliative care training, so-called generalist clinicians (Quill and Abernethy Reference Quill and Abernethy2013), who find it difficult to consider the nonphysical aspects of symptom burden (Chibnall et al. Reference Chibnall, Bennett and Videen2004; Carduff et al. Reference Carduff, Johnston and Winstanley2018). Previous studies have assessed barriers to the integration of psychosocial and spiritual care for patients with a serious or life-limiting illness. Identified barriers at the clinician level include a lack of attention for psychosocial and spiritual care in education and training (Chibnall et al. Reference Chibnall, Bennett and Videen2004; Page and Adler Reference Page and Adler2008; Balboni et al. Reference Balboni, Sullivan and Amobi2013), emotion interference with work (Botti et al. Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts2006; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017), clinicians lacking the vocabulary or communication skills to address the nonphysical dimensions (Chibnall et al. Reference Chibnall, Bennett and Videen2004; Vermandere et al. Reference Vermandere, De Lepeleire and Smeets2011; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017; de Graaf et al. Reference de Graaf, van Klinken and Zweers2020), clinicians’ unawareness of services or available resources to address nonphysical needs (Page and Adler Reference Page and Adler2008; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017; Koper et al. Reference Koper, Pasman and Schweitzer2019), and difficulties in interdisciplinary collaboration with psychosocial or spiritual care providers (Page and Adler Reference Page and Adler2008; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017). Other barriers were organizational issues, such as a lack of time, workload issues of clinicians (Chibnall et al. Reference Chibnall, Bennett and Videen2004; Botti et al. Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts2006; Balboni et al. Reference Balboni, Sullivan and Amobi2013, Reference Balboni, Sullivan and Enzinger2014; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017), and reimbursement issues (Chibnall et al. Reference Chibnall, Bennett and Videen2004; Page and Adler Reference Page and Adler2008; Koper et al. Reference Koper, Pasman and Schweitzer2019). These barriers to the integration of psychosocial and spiritual care have important implications for generalist clinicians’ accomplishments in integrating multidimensional symptom management in their daily practice. However, previous studies have not assessed barriers and facilitators to simultaneously assessing, treating, and reassessing multiple symptoms while also considering physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects. We aimed to identify the barriers and facilitators to multidimensional symptom management and potential solutions to improve clinical practice by exploring stakeholders’ experiences. We looked at 6 stakeholder groups: patient representatives, generalist community and hospital nurses, general practitioners (GPs), generalist hospital physicians, and palliative care specialists (nurses, physicians, psychologists, and spiritual caregivers).

Methods

Context

This study was part of the Multidimensional Strategy for Palliative Care research project (2017–2021; NCT03665168), a collaboration between the Centers of Expertise in Palliative Care of all 7 Dutch academic hospitals and the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization. These cooperating parties determined that national initiatives were lacking to improve the management of multiple simultaneously occurring symptoms while considering psychological, social, and spiritual aspects. Therefore, a project was designed to improve multidimensional symptom management in palliative care by studying the prevalence of multidimensional symptoms in a national cross-sectional study (De Heij et al. Reference De Heij, van der Stap and Renken2020), evaluating the acceptability of a clinical decision support system (CDSS) according to various stakeholders (van der Stap et al. Reference van der Stap, de Heij and van der Heide2021), assessing barriers and facilitators to multidimensional symptom management, developing symptom management recommendations for simultaneously occurring symptoms, and constructing a CDSS to support generalist clinicians.

Study design

We conducted focus group meetings to explore the experiences of stakeholders with barriers and facilitators to multidimensional symptom management and potential solutions to improve clinical practice and clarified their perspectives in an interactive process (Kitzinger Reference Kitzinger1995). The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research were used for reporting (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Focus group participants

To obtain a broad range of views and experiences, stakeholders with diverse backgrounds and who are usually involved in palliative care symptom management were included. Separate focus group meetings were conducted for different stakeholder subgroups to avoid potential hierarchical issues and dominance bias; participants were expected to feel inclined to talk more freely within their own subgroup. In total, 6 focus groups were established: (1) patient representatives, (2) generalist community nurses (working in nursing homes or in home care), (3) generalist hospital nurses, (4) GPs, (5) generalist hospital physicians, and (6) palliative care specialists (nurses, physicians, psychologists, and spiritual caregivers). A combination of purposive and convenience sampling of participants was used. Fifteen patient representatives from 2 palliative care patient councils were invited by email to participate in a focus group by one of the researchers (LvdS). There was no previous relationship between the invited patient representatives and the researcher. For focus groups 2–6, invitations to participate were distributed nationwide by email among clinicians via contact persons of the 7 Dutch Centres of Expertise in Palliative Care. Invitations contained participant criteria to distinguish if clinicians were generalist clinicians or palliative care specialists. Clinicians were considered palliative care specialists if they had completed 1 of the 3 dedicated Dutch palliative care training programs for nurses or physicians and/or were a member of a palliative care consultation team. All other clinicians were considered generalist clinicians. Focus group meetings involved a minimum of 6 and a maximum of 12 participants (Carlsen and Glenton Reference Carlsen and Glenton2011).

Data collection

A topic guide was developed to ensure standardization of focus groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Topic guide during focus group meetings

a In the case of patient representatives.

b In the case of clinicians.

Focus group meetings took place in 2019 in an external location and lasted approximately 2 hours. All meetings were led by a trained moderator (LvdS, female) and 1 or 2 assistant moderators (AdH, male; AvdH, female; and YvdL, female). No previous relationships were established between researchers and focus group participants. Notes were taken and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Identifiable participant details were removed.

Data analysis

Data were thematically analyzed using an inductive approach (Green and Thorogood Reference Green, Thorogood and Seaman2004; Nowell et al. Reference Nowell, Norris and White2017). First, 2 researchers (LvdS and AdH) individually read all notes and transcripts to become familiar with the data. A provisional coding tree was drafted by LvdS that included codes for topics that came up frequently. The transcripts were independently coded by 2 researchers (LvdS and AdH). After coding each transcript, codes were compared and adapted where necessary, resulting in a modified coding tree. Overarching themes were derived from the final coding tree and were discussed by the research team (LvdS, AdH, AR, AvdH, and YvdL). The final thematic framework was agreed upon by all team members. Participants did not give feedback on the findings. Atlas.ti software (version 8) was used for qualitative data analysis.

Results

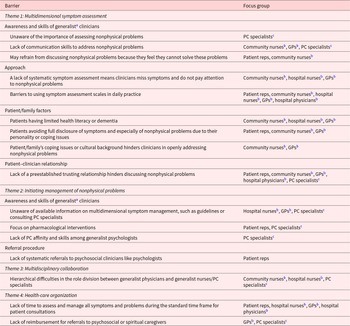

In total, 51 participants attended 6 focus group meetings. Out of 15 invited patient representatives, 6 participated. All 6 patient representatives had been informal caregivers of deceased patients. An overview of all participant characteristics is provided in Table 2. Data analysis identified barriers, facilitators, and potential solutions to improve multidimensional symptom management with 3 main themes: multidimensional symptom assessment, initiating management of nonphysical problems, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Barriers were also discussed with a fourth theme: health-care organization. The identified barriers, facilitators, and potential solutions are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 2. Characteristics of focus group participants

Reps: representatives; PC: palliative care; NA: not applicable.

a Generalist clinicians: clinicians without specialized palliative care training.

b The number of subdisciplines among hospital nurses and PC specialists exceeds the number of focus group participants because individual participants work in more than one subdiscipline.

c Working experience in current discipline in years.

Table 3. Barriers to multidimensional symptom management according to focus group participants

Reps: representatives; GP: general practitioner; PC: palliative care.

a Clinicians who are not specialized in palliative care.

b Generalist clinicians.

c Nurses, physicians, psychologists, and spiritual caregivers who are specialized in palliative care.

Table 4. Facilitators to multidimensional symptom management and potential solutions to improve clinical practice according to focus group participants

Reps: representatives; GP: general practitioner; PC: palliative care.

a Clinicians who are not specialized in palliative care.

b Generalist clinicians.

c Nurses, physicians, psychologists, and spiritual caregivers who are specialized in palliative care.

Theme 1: Multidimensional symptom assessment

Awareness and skills of generalist clinicians

Generalist clinicians reported that they have difficulties communicating with patients about nonphysical problems.

Well, in difficult situations you’re like, I’m detecting a problem […] how will I discuss it? I can see there is a problem, psychological or social, but how will I discuss it? (Hospital nurse 6)

A generalist community nurse mentioned that providing standardized questions to address nonphysical problems could be a potential solution for overcoming these difficulties.

We’ve once asked our spiritual caregiver to give us tools for approaching the conversation. Those were just simple questions, like, what still gives you energy or what do you like? (Community nurse 10)

Another generalist community nurse felt that generalist clinicians may not address nonphysical problems because they feel they cannot solve them, which was also acknowledged as a barrier by a patient representative.

My husband’s short temper was the worst. And the oncologist said “yes, I hear that a lot”. And later he said to me, “I mostly don’t ask about it because I don’t have anything against it but I realise that by doing that, I’m kind of giving it the silent treatment.” (Patient representative 4)

A generalist hospital physician experienced that addressing nonphysical problems is facilitated just by listening to patients instead of immediately aiming to solve their symptoms and problems. As mentioned by generalist clinicians themselves, palliative care specialists experienced that generalist clinicians have difficulties communicating with patients about nonphysical problems.

In fact, all nurses said that they couldn’t find the right words for it, for those existential things, so they don’t know how to talk about it, while they do pick up on it. But they don’t have the tools to discuss it. So, that was the biggest issue that nurses experienced. (Palliative care specialist 8)

Palliative care specialists also felt that generalist clinicians often seem unaware that assessing nonphysical aspects of symptom burden is important. Specialists based this on their experience that their advice is predominantly requested for the management of physical symptoms and that generalist clinicians frequently cannot describe the psychological, social, or spiritual situation of their patients during palliative care consultations.

The clinician’s approach to symptom assessment

Generalist clinicians associated not having a systematic approach to symptom assessment with not noticing simultaneously occurring physical symptoms and not paying attention to nonphysical problems.

Because the patient initially mostly brings up the physical components too […] and I detect that I’m often reactive to that. While I would prefer it if those other components get attention. (GP 6)

Generalist clinicians mentioned that making explicit efforts to understand how symptoms and problems interact helps them to manage symptoms and problems that occur simultaneously.

What I do recognize is that for some complaints it’s important to gain insight into where they come from. Someone is nauseous, but why? A pill is easily prescribed, but you have to invest in that. Otherwise, you can have someone who’s not happy daily on the phone. (Hospital physician 7)

One thing leads to another, one symptom leads to the other, or the start of an intervention, and gaining insight in that … Yeah, I always like to write things down. You sometimes get, well, you can connect things if you write them down next to each other. Then sometimes, suddenly, you can see connections. (Community nurse 9)

It also helps them to ask their patient whether the symptom they report requires relief, in contrast to the clinician assuming that the patient wants treatment. It also helped to ask their patient to prioritize their symptoms.

What I think is important in symptom management too […] is that you assess what is of main interest for the patient. So what’s the most important complaint for them, that burdens them the most, that you could address. (Community nurse 1)

As a potential solution to improve multidimensional symptom assessment, generalist clinicians suggested the use of a symptom assessment scale (SAS) to identify multiple simultaneously occurring symptoms. Patient representatives and palliative care specialists also believed that the use of an SAS may help. It was mentioned that an SAS reminds clinicians to ask questions that they might otherwise forget to ask and that its use provides insight into symptom severity, which may otherwise be overlooked. Also, clinicians thought that if an SAS was filled out prior to consultations, it can help clinicians prioritize what symptoms and problems to discuss. A generalist nurse mentioned that filling out SAS scores helped her to monitor if an intervention was successful in relieving symptoms.

I think that as doctors we always think that we ask about all complaints, also those that are not necessarily cancer symptoms, but you don’t always do that, you frequently don’t. And it helps you to consider those other symptoms. There really are questions on an SAS that are not in my standard vocabulary. (Hospital physician 7)

Yes, to gain insight into how severe a patient experiences a symptom. And, in my opinion, that can only be expressed well with a number. I think it’s a very useful tool. Otherwise, you just can’t really put yourself in the patient’s shoes. And then afterwards, that’s the good thing, if you start an intervention, you can see if it had an effect, if it did something. (Hospital nurse 1)

However, generalist clinicians expected barriers to using an SAS. They were wary of having to fill in yet another list and thought it burdensome for patients and believed that these scoring systems are not suitable for several patient subgroups. Community nurses mentioned that an SAS is not suitable to evaluate symptoms of people with dementia because it has not been adapted to their ways of communicating and understanding written information. Community nurses and GPs also noticed that their patients’ level of health literacy had an impact on the patients’ understanding of the value of symptom scores and their willingness or unwillingness to fill out the questionnaire. Generalist community and hospital nurses experienced that if patients have acute exacerbations of their symptoms, the sense of urgency to relieve symptom burden leaves no mental room for patients or clinicians to fill out an SAS. Both generalist clinicians and patient representatives considered SAS scores difficult to interpret because they believed these scores do not always reflect the actual symptom burden.

I think about lists with scores, that it’s sometimes difficult that people can’t really say how they would rate it. Sometimes the score doesn’t match what they truely experience but they provide a rating because they have to. (GP 5)

Patient and family factors

Generalist community nurses, hospital nurses, and hospital physicians reported difficulties identifying all physical symptoms and nonphysical problems in patients with limited health literacy or dementia. A patient representative mentioned that patients may not mention nonphysical problems because these problems are more difficult to discuss than physical symptoms are.

People don’t talk about mental stuff easily; personal fulfilment, that only comes up at a later stage. The physical part is the first thing you encounter, and that often gets the most attention as well. (Patient representative 1)

Generalist clinicians experienced that coping issues, such as the patient or their family not accepting the illness, or impending death, or the patient and their family having a different cultural background than the attending clinician, make it more difficult for clinicians to address nonphysical problems. Patient representatives, generalist community nurses, and GPs also found that patients may not fully disclose their symptoms and nonphysical problems because of their personality or coping strategies. Generalist community nurses and GPs found it helpful to tailor their communication methods to those patients who do not fully disclose their symptoms and problems. They do this by observing nonverbal signs and signals, such as reflecting on their own impression of whether the patient is comfortable, by observing the patient’s surroundings when they are in their own home, by observing the way their informal caregivers act, or in case of pain, by reviewing how many times patients used their breakthrough medication.

So, regarding pain, I think I frequently work with breakthrough medication, so if they don’t indicate clearly how much pain they have, I look at how often they used that medication, that gives an indication of how much pain they have. (GP 5)

They also tended to ask more indirect questions about nonphysical problems.

I detect that in our nursing home, plainly asking questions about end-of-life issues in those other dimensions is difficult. And then you ask, “what still brings you joy?” … The dog, the daughter. Then in the end, you get there. (Community nurse 10)

Participants also mentioned not addressing all potential nonphysical problems at once but gradually, during multiple consultations. A GP found it easier to assess nonphysical problems if the patient had experience thinking about spirituality or death before receiving palliative care. This experience may come from religious convictions or the death of someone close to them.

What also helps is that some people have had a whole spiritual life, and they have often thought about their spirituality. I recently had a man who was anthroposophical, and he really had some kind of resignation. So, you can also draw upon what they’ve made their own. (GP 4)

Patient–clinician relationship

Patient representatives, generalist clinicians and palliative care specialists mentioned that it makes it easier to discuss nonphysical problems if clinicians and patients have an established and trusting relationship. Patients are more inclined to share nonphysical problems, and clinicians are more inclined to address these problems if the clinician knows the psychosocial and spiritual status of their patient. Having no or little relationship was considered a barrier that, for example, hinders multidimensional symptom assessment in situations when a patient’s own clinicians are not present, such as outside of office hours.

If you’ve been involved since the diagnosis, then I feel like I have a fundamental understanding of the situation, I get it, I know the person well. Then it can still be difficult for lots of reasons, but I have the feeling that I’m in control. If you’re involved later, for example during outside office hours, I have the feeling that it’s a little late. Then it’s very often only about the physical component, and I really have to remind myself that the other components are just as important. (GP 6)

But that might be because patients don’t want to talk if they see a different doctor every time. Because if you see the same doctor every time, you may be more inclined to expose yourself, like, I dare to tell something. But otherwise it’s like, who will it be next week? (Palliative care specialist 5)

Theme 2: Initiating management of nonphysical problems

Awareness and skills of generalist clinicians

GPs mentioned that they are unfamiliar with referring patients to spiritual caregivers, so often forget to do so. Generalist hospital nurses experienced that generalist physicians do not know how to inform themselves about multidimensional symptom management and are not aware of the available resources, such as guidelines or palliative care specialists, which was also mentioned by palliative care specialists.

Well, physical is mostly ok, because a doctor has been trained for that, but often for the other dimensions, like, which tools exist in the palliative care setting? You have the national palliative care symptom guidelines, other ones, national oncology guidelines, also have a lot of information. They’ve often never heard of that, let alone of a palliative care consultation team. They don’t know what’s available. (Hospital nurse 3)

Palliative care specialists also felt that generalist clinicians are often unaware of available information on multidimensional symptom management. Palliative care specialists and patient representatives believed that generalist clinicians may not initiate multidimensional management because they focus on pharmacological interventions. A palliative care psychologist thought that insufficient palliative care skills among generalist psychologists prevent adequate treatment of nonphysical problems.

There are very few psychologists with palliative care affinity and I really believe that’s a problem. I barely know any colleagues who find that interesting. Young colleagues find it scary, and if I teach psychologists, they look at me like, what are you doing? I find this scary, what are you talking about? And they are absolutely not equipped. I worry about the spiritual dimension, but also about the psychosocial dimension. There really is a lack of attention, also within the profession. (Palliative care specialist 2)

Referral procedure

Patient representatives mentioned that referrals of patients and their family to psychologists not being done systematically in palliative care is a barrier to multidimensional symptom management. They expected that systematic referrals would be a potential solution.

If your doctor would say, “this is part of the care trajectory, it’s totally normal and everyone gets a referral.” Then afterwards, you know how to find help if you need it, which is a very good thing in my opinion. (Patient representative 4)

Multiple patient representatives had experienced that it facilitates multidimensional symptom management if patients or their family members themselves initiated referrals to, for example, psychologists or psycho-oncological care centers for help with nonphysical problems.

Theme 3: Multidisciplinary collaboration

Generalist and specialist clinicians felt that collaboration of generalist clinicians with other disciplines, such as specialist palliative care teams, psychologists, spiritual caregivers, and social workers, facilitated multidimensional symptom management. Generalist community and hospital nurses mentioned scheduling multidisciplinary meetings with generalist and specialist clinicians as a solution for improving the clinical practice of generalist clinicians because it helps them to address all dimensions of palliative care. This was also the experience of palliative care specialists.

As of recently, we’ve been doing case discussions every 2 weeks with someone from the palliative care consultation team, according to the decision-making in palliative care method and palliative reasoning. We do this with a group of people and discuss the 4 dimensions, and then you often encounter things that you haven’t thought of before. Even though you’ve been taking care of the patient for 3 days, you still missed them. (Hospital nurse 2)

Generalist community nurses, hospital nurses, and palliative care specialists reported that hierarchical difficulties in the division of roles between disciplines are a barrier to multidimensional symptom management. For example, generalist community and hospital nurses sometimes wanted to refer their patients to other disciplines, such as occupational therapists, community workers, complementary health-care professionals, or palliative care specialists but felt unable to do so because physicians were hesitant about nurses making these referrals.

So, as a home care nurse it is kind of testing the waters. With whom may I say, maybe an occupational therapist? Some GPs are OK with that, others are like, wow, you’re now taking over my control. You can’t. (Home care nurse 3)

Palliative care specialists indicated that they feel that their multidimensional approach is not always appreciated by generalist physicians. This may prevent palliative care specialists from addressing nonphysical aspects of symptom burden and non-pharmacological interventions during consultations.

It’s dragging, pushing, luring, to make your consultation valuable. You often aren’t even allowed to ask additional questions. […] You aren’t always valued as a consultant in my experience. (Palliative care specialist 1)

Theme 4: Health-care organization

Having enough time for patients was considered a prerequisite for comprehensive symptom management. However, patient representatives and many generalist clinicians regarded the standard time frame for consultations insufficient for assessing and treating all potential physical symptoms and nonphysical problems. In addition, GPs and palliative care specialists reported that reimbursement issues can make referring patients for nonphysical problems difficult. For example, referral to centers for psycho-oncological care is not reimbursed for patients without a formal psychiatric diagnosis such as depression, even if the patient would benefit from such a referral. Palliative care specialist also reported that despite the benefits of referring patients who reside at home to psychosocial or spiritual care providers, the possibilities are limited because this care is mostly not reimbursed.

And spiritual care at home, that’s a point of attention. We have a project where the spiritual caregiver visits patients in their home and it works very well, but that’s only possible to a limited extent. (Palliative care specialist 6)

It’s not allowed actually, because you can’t claim the costs. And that’s a problem for psychologists and social workers as well. (Palliative care specialist 1)

Discussion

This study identified barriers and facilitators to multidimensional symptom management in palliative care and potential solutions to improve clinical practice. Multidimensional symptom management was defined as the simultaneous assessment, treatment, and reassessment of multiple symptoms while considering physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects. Patient representatives, generalist nurses, generalist physicians, and palliative care specialists discussed barriers, facilitators, and potential solutions with 3 main themes: multidimensional symptom assessment, initiating management of nonphysical problems, and multidisciplinary collaboration.

The barriers identified in our study are similar to the barriers identified in previous studies on the integration of psychosocial and spiritual care. However, we identified several factors regarding the awareness or skills of generalist clinicians as barriers that were not described in previous studies. From the perspective of palliative care specialists, generalist clinicians appear to be unaware of how important assessing nonphysical problems is for managing symptom burden and they focus primarily on pharmacological interventions. Moreover, our study identified that psychosocial generalist clinicians such as psychologists may also have insufficient palliative care skills, preventing adequate management of nonphysical problems. In addition, this study confirmed that several skills are insufficient among generalist clinicians that have been previously reported as barriers to the provision of psychosocial and spiritual care. Both generalist clinicians and palliative care specialists pointed out that generalist clinicians do not seem to know where they can find information about multidimensional symptom management, such as guidelines or consulting palliative care specialists (Page and Adler Reference Page and Adler2008; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017; Koper et al. Reference Koper, Pasman and Schweitzer2019). Generalist clinicians felt uncertain about their communication skills and lack the vocabulary for addressing nonphysical dimensions (Chibnall et al. Reference Chibnall, Bennett and Videen2004; Botti et al. Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts2006; Vermandere et al. Reference Vermandere, De Lepeleire and Smeets2011; Best et al. Reference Best, Butow and Olver2016b; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017) and mentioned that they are unfamiliar with referring patients to clinicians like spiritual caregivers (Assing Hvidt et al. Reference Assing Hvidt, Søndergaard and Ammentorp2016; Koper et al. Reference Koper, Pasman and Schweitzer2019).

This study has also revealed potential solutions that could support generalist clinicians in improving multidimensional symptom management. These include using SASs and providing clinicians with standardized questions that address nonphysical problems. Many multidimensional assessment tools for palliative care have been described (Aslakson et al. Reference Aslakson, Dy and Wilson2017) but those that are widely used in clinical practice, such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (Hui and Bruera Reference Hui and Bruera2017), only address physical symptoms and psychological problems (Aslakson et al. Reference Aslakson, Dy and Wilson2017). To fully establish multidimensional symptom management, tools that assess all 4 dimensions of palliative care should be further implemented, such as the Palliative Care Outcome Scale (Hearn and Higginson Reference Hearn and Higginson1999), the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Palliative Care (Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Bakitas and Hegel2009), The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire – Revised, (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Russell and Leis2019), or the Utrecht Symptom Diary-4 dimensional (de Vries et al. Reference de Vries, Lormans and de Graaf2021). The use of 4-dimensional assessment tools may increase awareness among generalists of the importance of addressing nonphysical problems, in addition to offering a systematic approach to multidimensional assessment and standardized questions for addressing nonphysical dimensions. Increasing awareness of clinicians is a key step toward integrating the concept of multidimensional symptom management into daily clinical practice (Grol and Wensing Reference Grol and Wensing2004).

This study also confirmed patient factors as barriers to multidimensional symptom assessment. In general, patient representatives and clinicians reported that patients find nonphysical problems more difficult to discuss than physical symptoms. Previous studies have found that patients often express their needs in the nonphysical dimensions during consultations, but they do this through subtle and indirect cues that clinicians often fail to recognize (Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Del Piccolo and Finset2007; Mjaaland et al. Reference Mjaaland, Finset and Jensen2011; Beach and Dozier Reference Beach and Dozier2015; Brandes et al. Reference Brandes, Linn and Smit2015). Education and training of clinicians to adequately recognize and respond to such cues could facilitate the assessment of nonphysical problems. In particular, the clinicians in our study found it difficult to adapt their communication to respond to the needs of their patients who had difficulty coping, did not feel comfortable to discuss nonphysical problems, or had a different cultural background than the attending clinician. Other studies identified similar challenges in patient–clinician communication in general (Nutbeam Reference Nutbeam2000; Meeuwesen et al. Reference Meeuwesen, Tromp and Schouten2007), discussing end-of-life issues (Hancock et al. Reference Hancock, Clayton and Parker2007) and discussing the spiritual dimension (Vermandere et al. Reference Vermandere, De Lepeleire and Smeets2011, Reference Vermandere, Choi and De Brabandere2012; Best et al. Reference Best, Butow and Olver2016a). Improving the ability of clinicians to adapt their communication skills to the needs of their patients could help overcome these barriers. Using a patient-reported 4-dimensional SAS could also help by preparing patients for these discussions. It may also help to educate patients about interactions between physical symptoms and nonphysical problems. Personalized education on pathophysiological mechanisms has been shown to empower patients with life-limiting illnesses (Wakefield et al. Reference Wakefield, Bayly and Selman2018) and knowing why nonphysical problems are addressed during consultations could prompt them to disclose those problems.

This study confirmed that a trusting and established clinician–patient relationship helps both the patient and the clinician to discuss nonphysical problems. This is in line with previous findings that a trusting clinician–patient relationship is a facilitator or even an important foundation for the provision of holistic care (Mok and Chiu Reference Mok and Chiu2004; Botti et al. Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts2006; Vermandere et al. Reference Vermandere, De Lepeleire and Smeets2011, Reference Vermandere, Choi and De Brabandere2012; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Best and Mitchell2020). Previously identified factors that contribute to a trusting patient–clinician relationship are the clinician displaying caring actions and attitudes, passion, competency, understanding of the patient’s needs and complex medical history, and interest in patients and their family (Mok and Chiu Reference Mok and Chiu2004; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017). Also contributing is providing holistic care in itself (Mok and Chiu Reference Mok and Chiu2004), continuity of care (Botti et al. Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts2006), and mutuality, meaning the patient also knows the clinician to some degree (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Best and Mitchell2020). Unfortunately, patients at the end of life often move between care settings (Van den Block et al. Reference Van den Block, Pivodic and Pardon2015), meaning an established clinician–patient relationship is often missing. These situations may hinder discussion of nonphysical problems, stressing the importance of exchanging information on a patient’s psychosocial and spiritual status during handovers, which often does not happen (Mertens et al. Reference Mertens, Debrulle and Lindskog2021).

In line with previous literature, an important finding of our study is that generalist nurses and palliative care specialists reported difficulties in multidisciplinary collaboration as barriers to multidimensional symptom management. They experienced hierarchical difficulties in the role division between them and generalist physicians. Nurses did not feel comfortable referring patients to paramedical or psychosocial caregivers because generalist physicians sometimes disapprove of nurses taking charge. Palliative care specialists indicated that their multidimensional approach is not always appreciated by generalist physicians, which prevents them from encouraging multidimensional symptom management. Interdisciplinary communication difficulties have previously been reported as barriers to multidimensional care (Botti et al. Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts2006; Page and Adler Reference Page and Adler2008; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Hsieh2017; de Graaf et al. Reference de Graaf, van Klinken and Zweers2020). Issues with role boundaries between different disciplines have also been reported in psychosocial palliative care (O’Connor and Fisher Reference O’Connor and Fisher2011), and the particular collaboration problems between generalists and specialists have been described as “professional territorialism” (“an unspoken demarcation between health professionals, regarding who coordinates and provides patient care”) (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Gott and Ingleton2012). Our participants suggested that multidisciplinary team meetings are a potential solution for improving multidimensional symptom management. It is important to note that multidisciplinary team meetings in oncology and hospices are usually physician-led and that nurses and other disciplines rarely participate, at least not on an equal basis (Wittenberg-Lyles et al. Reference Wittenberg-Lyles, Gee and Oliver2009; Lamb et al. Reference Lamb, Taylor and Lamb2013; Rosell et al. Reference Rosell, Alexandersson and Hagberg2018; de Graaf et al. Reference de Graaf, van Klinken and Zweers2020). This climate will likely prevent that multidisciplinary meetings help overcome the reported hierarchical difficulties and will cause the focus of meetings to be on biomedical information rather than on psychosocial and spiritual concerns. Improving the awareness among generalist physicians about the importance of considering nonphysical problems during symptom management may allow palliative care specialists to discuss these problems during consultations. In addition, it may help if the role of generalist nurses is clearly defined because they may be key in advancing multidimensional symptom management as implied by our own and previous findings (Henry et al. Reference Henry2018). Indeed, generalist nurses have a more multidimensional view of patient health, whereas physicians tend to have a narrower and more biomedical view (Huber et al. Reference Huber, van Vliet and Giezenberg2016).

Strengths and limitations

Participating generalist clinicians may have had more affinity with palliative care than nonparticipants because of the combined purposive and convenience sampling (nonresponse bias) and patient representatives may have had more proactive attitudes toward care than average patients do. This may mean that the reported experiences with barriers and facilitators do not reflect those of the general clinician and patient populations, which may limit the generalizability of our results. A strength of the study is that the experiences of a broad group of stakeholders from different disciplines and settings were evaluated, including patient representatives, representing the multidisciplinary nature of palliative care. This way, barriers and facilitators to the complete process of multidimensional symptom management could be identified.

Conclusion

Multidimensional symptom management can be improved by helping generalist clinicians to improve their communication skills for addressing the nonphysical dimensions. It may also help to increase their awareness of the importance of assessing the nonphysical dimensions and of available resources for multidimensional symptom management, such as symptom management guidelines and consultation of palliative care specialists. Generalist clinicians should be encouraged to use systematic approaches to help identify physical symptoms and nonphysical problems that would otherwise be overlooked and to help prioritize which subjects to discuss during consultations. It should be noted that several generalist clinicians had negative attitudes toward using a systematic approach and that these approaches may not be suitable for all patients and situations, like in case of patients with limited health literacy or in case of acute symptom exacerbations that require urgent relief. Organizational barriers that should be targeted to improve clinical practice are reimbursement issues for care that targets nonphysical problems and clinicians having insufficient time for multidimensional symptom management.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all focus group participants and the collaborating partners of the MuSt-PC project: the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL) and the 7 Centres of Expertise in Palliative Care of the University Medical Centre Groningen, Radboud University Medical Centre, Amsterdam University Medical Centre, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Leiden University Medical Centre, University Medical Centre Rotterdam, and Maastricht University Medical Centre.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Research ethics and consent

The Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) Medical Ethical Research Committee reviewed the research protocol (study number P18.236) and provided a waiver (11 March 2019). Participants gave written informed consent for data collection and processing and for the publication and sharing of the study data and results.