The motets in the fourteenth-century Italian liturgical manuscript Oxford, Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42 (henceforth e. 42) have, despite some sidelong glances, not been the subject of any concentrated study since F. Alberto Gallo introduced them in 1970.Footnote 1 Gallo dated this manuscript around the middle of the fourteenth century, but I propose an earlier date range for the copying of the main part of e. 42, placing it within the first decades of the century.Footnote 2 This manuscript and its motets further recent scholarly approaches to the early fourteenth century in three distinct ways. First, they underline the importance of considering polyphony within the context of the entire manuscript that transmits it: such a ‘whole book’ approach demonstrates that e. 42's motets work together with its monophonic chant to emphasise a set of feasts which were particularly important for the compilers of this manuscript within their institutional context, including Corpus Christi, Ascension and feasts of the Holy Cross.Footnote 3 Second, these motets act as a reminder of the survival of Ars Antiqua repertoire into the fourteenth century and stress that narratives of stylistic change must be heterogenous: I demonstrate the wide-ranging mix of musical styles found in the motets of e. 42 and argue that they add to an emerging picture of early fourteenth-century sources where stylistic eclecticism is a common feature.Footnote 4 Third, e. 42's notation and its connections to that of other manuscripts enrich and complicate narratives of notational change in this period. Parallels for e. 42's ligature use can be found in a temporally and geographically diverse set of manuscripts. Its notation of semibreves, however, resembles that of a smaller group of manuscripts from the early fourteenth century and provides vital evidence in tracing the development of norms for semibreve rhythm in both Italian and French music theory.Footnote 5

The provenance, contents and date of e. 42

The provenance of e. 42 is securely established. An ex libris on the final folio (143r) identifies it as belonging to the Chapel of St George within the Collegiate Church of St Stephen, Biella, which lies between Milan and Turin.Footnote 6 In the early fourteenth century, Biella's closest political and ecclesiastical links were with the Bishops of Vercelli and their Cathedral of St Eusebius, some forty kilometres southeast, so e. 42's provenance is further confirmed by its special attention to the patron saints of Biella and Vercelli.Footnote 7 After an opening Credo (Credo I, fol. 1v), a troped Benedicamus domino for St Stephen (Servus dei stephanus) is the second item in the manuscript (fol. 3v).Footnote 8 The Mass for St Eusebius, meanwhile, is the second Mass in the book (fol. 30v), after one for the Virgin Mary (fol. 24v).Footnote 9

This practically sized book, with leaves measuring 210 mm × 153 mm, bears extensive marks of use.Footnote 10 As outlined in Table 1, its main part (fols. 30v–111v) transmits Mass Propers, prayers, readings and prefaces without musical notation. The first of two notated sections opens the manuscript: after the monophonic Credo and trope for St Stephen follow three complete three-voice motets (fols. 4r–6r), notated in two columns, each with seven six-line red staves.Footnote 11 Such six-line staves, common in fourteenth-century Italian polyphonic manuscripts, are very rare in earlier motet manuscripts, which used five-line staves.Footnote 12 At least one more motet was once notated on fols. 6v–7r. Although this music was later scraped away to make room for unnotated prayer texts, enough remains visible under UV light to identify the motet (as demonstrated below). The manuscript continues with a series of monophonic eucharistic prefaces for important feasts, notated on four-line staves (fols. 7v–14r). Within the ordo and canon of the Mass (fols. 14v–24v) notation is given for some sung items such as the Lord's Prayer (fol. 22r–v). The final notated item in this opening section is the first full Mass, for the Virgin Mary (Maria in Sabbato V; fols. 24v–30r), which is the only Mass with the notated Ordinary (fols. 27r–29v). The second notated section (fols. 112r–127v) provides monophonic notation on four-line staves for the sung items of a selection of Masses whose texts appear earlier in the book. Some of these feasts were valued universally, such as Christmas and Pentecost, while others were of local importance, such as Eusebius, who opens this section (fols. 112r–113v).

Table 1. Contents of e. 42

The chronological sequence of copying is recoverable, at least in outline. Most of the manuscript seems to have been written in a single copying project. According to Leo Eizenhöfer, fols. 1–127 are in the same text hand.Footnote 13 The codicological structure, as summarised in Table 1, suggests that this scribe copied at least the material on fols. 4–111 in one campaign; within this range of folios, no major content-based section breaks coincide with a new gathering.Footnote 14 Although the second notated section of the manuscript (fols. 112–127) opens a new gathering, it also seems to belong to the main copying campaign, as it has the same text hand and similar strategies of feast selection, musical notation and artistic decoration.Footnote 15 The place of the opening codicological unit (fols. 1–3) within this main campaign is trickier. Originally a binio, its first folio, now present only as a stub, must have been removed by the time of the manuscript's foliation, in which it is not included. This gathering's text is written by Eizenhöfer's main scribe, although it has a different decorative strategy from that used in fols. 4–127.

Although Gallo suggested a date for e. 42 around the mid-fourteenth century, the notated Corpus Christi mass in the second notated section (fols. 120r–127r) suggests that the main copying campaign (comprising at least fols. 4–127) happened in the first decades of the century.Footnote 16 The decision to add this Mass was clearly a late one, as – unlike the other notated Masses – its text is not found in the unnotated part of the manuscript. Instead, the full liturgical texts are presented in the notated section, which is otherwise restricted only to the sung items. This late entry implies that e. 42's version of the Corpus Christi Mass was current during the main campaign of copying. Although the feast was established in the Diocese of Liège in 1246, Urban IV's attempt to elevate the feast to universal observance in 1264 was foiled by his death soon afterwards. This universalisation was only fully achieved with the Clementines, a canon law collection propagated in 1317.Footnote 17 Different iterations of the feast's liturgy were produced along this timeline, with the three basic versions being labelled A, B and C by Thomas J. Mathiesen.Footnote 18 A was the early Liège Office, probably composed by the feast's instigator Juliana. Versions B and C are now generally thought to result from Urban's request to Thomas Aquinas to create a liturgy for the new feast: B was an interim version that allowed Urban to celebrate the feast in 1264, whereas C was the revised version which Urban meant to promulgate in his intended universalisation of the feast.Footnote 19 This later C version became fully standard during the implementation of universalisation after 1317, with B largely only retained in Troyes, the city of Urban's birth.Footnote 20 The version of the Mass in e. 42, which begins with the introit Ego sum panis vivus, is that linked by Pierre-Marie Gy to B.Footnote 21 Biella likely obtained this version through Vercelli. While Thomas Aquinas was at the Papal Court in the 1260s, he formed a friendship with Jacobus de Tonengo, a canon of Vercelli who became the addressee of Thomas's De sortibus.Footnote 22 Jacobus could easily have brought a copy of the B version to Vercelli (and thereby Biella) after his time at the papal court. Given the general ascendancy that C gained after the universalisation of the feast, though, it seems less likely that the Biella scribes could have copied the B version of the Mass much after 1317. With allowance for a variable pace of liturgical change, this places the copying of e. 42's Corpus Christi Mass, and of the polyphonic music copied in the same campaign, within the first decades of the fourteenth century.Footnote 23

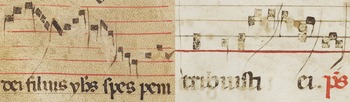

There were three groups of changes that post-dated this main stage of copying. First, at least one campaign of musical checking and revision may have occurred soon after, or even as part of, the main stage. In both polyphonic and monophonic repertoires, this resulted in curvy lines that clarify the relationship between music and text, as seen in Figure 1. This campaign also seems to have resulted in the correction of some pitch errors in the motets, as shown by the large erasure on fol. 5v (Figure 1, left image). Further revision of the motets’ notation of semibreves, discussed later, may also have occurred at this stage. The second group of changes likely took place once the polyphonic repertoire fell out of use: the music on fols. 6v–7r was scraped and replaced by prayer texts.Footnote 24 The third group of changes, the later campaign of copying on fols. 128r–142v, is not considered in this study.Footnote 25

Figure 1. Musical corrections to the triplum of Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra /[Tenor] (fol. 5v, left) and to the plainsong introit for the feast of St Eusebius (fol. 112r, right). Images from Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

The motets of e. 42 and their liturgical connections

The motets of e. 42, although published by Gallo, have not fully been taken into account by scholars of thirteenth-century motets, probably because e. 42 was not listed in the standard catalogues by Friedrich Ludwig, Friedrich Gennrich and Hendrik van der Werf.Footnote 26 The function of these motets within e. 42 has not been considered at all. This manuscript, however, provides a valuable reminder of the importance of approaching manuscripts containing polyphony as whole books, since its motets combine with its other notated music to celebrate feasts that seem to have been especially significant within the institutional context of the compilers.Footnote 27

The first motet, which is unique to e. 42, is monotextual: both upper voices sing the text Ave vivens hostia. Unlike other contemporary and earlier manuscripts, which generally copy the upper voices of monotextual motets in score, e. 42 presents this motet in parts, with the triplum on the left, the motetus on the right, and the tenor running along the bottom (Figure 2).Footnote 28 The Latin text is pre-existing, comprising the first stanza and the first half of the fifteenth stanza of the Corpus Christi text of the same name attributed to the Franciscan John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury (1279–92).Footnote 29 Along with the Corpus Christi Mass in the second notated section of the manuscript (fols. 120r–127r), the Ave vivens motet demonstrates the importance of this feast in Biella.

Figure 2. Ave vivens hostia/ Ave vivens hostia/ Organum (Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fol. 4r). Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

The tenor is curiously labelled ‘organum’; this unusual designation may be intended to recall the chant tenor of an organum and thereby suggest that this lowest voice uses unidentified pre-existing material.Footnote 30 As the tenor's rhythm would allow it to present the same text as the upper two voices, however, it is more likely that the three voices were conceived in a conductus-like texture and then only notated separately by the e. 42 scribe, who chose not to text the lowest voice, perhaps for reasons of space. This posited change in format may have been intended to enable this piece to appear on a single folio at the beginning of a gathering prepared for the copying of motets, like the opening Deus in adiutorium settings typical of this period.Footnote 31 If the scribe were copying from an exemplar in score, this would also account for some anomalies of layout and notation: the text often leaves insufficient space for the notation, which responds by resorting to ligatures that produce strange text rhythms (triplum line 1, over ‘hostia’) and ligatures which set more than one syllable (motetus line 2, over ‘vita’).

The second motet in e. 42, Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra/ [Tenor] (Figure 3), has one concordance: its triplum and tenor are found as a two-voice motet in the polyphonic collection at the back of the Florence Laudario (fols. 148v–149v), dated to the second quarter of the fourteenth century.Footnote 32 The triplum text, Dulcis Jesu memoria, is again pre-existent, comprising the first four stanzas of a text historically attributed to St Bernard of Clairvaux but now considered more likely to be by an anonymous English Cistercian.Footnote 33 The motetus text in e. 42 begins with the first two stanzas of the Ascension hymn Jesu nostra redemptio and continues with O Jesu per opera: a concordance for this latter text is found in a fragmentary cantilena in Reconstruction III of the Worcester Fragments.Footnote 34 The tenor of this motet, which bears no label in e. 42, consists of three cursus of a melody whose ambitus and ductus look reasonably like that of a chant melisma, although I have not found any credible matches.

Figure 3. Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra/ [Tenor] (Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fols. 4v–5r). Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra is linked to numerous feasts of special importance in Biella. The motetus begins with a hymn for Ascension, matching the inclusion of this feast in the collection of notated prefaces (fol. 9r–v). The triplum's Dulcis Jesu text broadens the motet's referential field. As Matthias Standke argues, Dulcis Jesu focuses on Christians’ ability to sense Christ's presence by means other than his bodily presence on earth.Footnote 35 Standke advocates for the importance of the Easter–Ascension–Pentecost sequence: all three of these feasts are represented in e. 42's collection of prefaces (fols. 8v–9r, 9r–v and 9v–10r, respectively) while Pentecost is also found in the notated Masses (fols. 116v–118r). Furthermore, Helen Deeming, in her analysis of an unrelated twelfth-century monophonic setting of Dulcis Jesu, demonstrates that this text foregrounds perceiving Christ's presence through taste.Footnote 36 In the context of e. 42, this invites a connection with Corpus Christi, whose importance has already been established.Footnote 37 In e. 42, therefore, Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra once again reinforces the liturgical priorities of the manuscript as a whole, pulling out themes from numerous feasts afforded prominence by the compilers.

The third motet (Figure 4) addresses another feast of importance in e. 42: the upper voices of O crux admirabilis/ Cruci truci domini/ [Portare] are for the Holy Cross, and its here unlabelled tenor is drawn from the Alleluia verse for that feast, Dulce lignum dulces clavos. The melisma used for the tenor, labelled Portare in two concordant copies of the motet, matches the version of the same melisma in e. 42's Mass for the Holy Cross in the second notated section of the manuscript (fol. 115r).Footnote 38 This motet, along with the inclusion of the feasts of the Holy Cross in both the second notated section (fols. 113v–116v) and in the collection of prefaces (fol. 8v), provided Biella with material to celebrate a feast which was important to them.

Figure 4. O crux admirabilis/ Cruci truci domini/ [Portare] (Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fols. 5v–6r). Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

This motet has musical concordances in better-known motet sources: the same music is found both in the seventh fascicle of Mo (fols. 279r–280v) and in Tu (fols. 17r–18v), here with the French texts Plus joliement/ Quant li douz tans/ Portare. In all versions, the triplum frequently places two syllabic semibreves for a breve, while the motetus does so more sparingly. The version in e. 42 has three principal points of interest. First, it is the only manuscript to have the motetus incipit Cruci truci domini, the text that accompanies this music when it is cited as an example in the treatise Ars musicae mensurabilis secundum Franconem as transmitted in Paris, BnF lat. 15129 (fols. 1r–3r).Footnote 39 Second, its motetus introduces melismatic groups of four semibreves per breve, not found in either the Mo or Tu versions. Third, as discussed later, some of e. 42's semibreves have upstems, relating them to the many experimental ways of notating short note-values occurring in sources after 1300.

The fourth motet in e. 42, originally entered on fols. 6v–7r (Figure 5), has been largely scraped away to make room for unnotated prayer texts. Enough is visible under UV light, however, to identify this motet as Iam novum sydus/ Iam nubes dissolvitur/ [Solem]. Along with key passages of the upper voices, UV light reveals the entirety of the tenor notation, transcribed in Example 1. As usual for e. 42, only one out of the four cursus of the Solem melisma is written out. Importantly, e. 42's version of this tenor appears to notate its final double long with two vertical lines through it: this method of marking the number of perfect longs contained in a note is known from early fourteenth-century theoretical sources but is very rare in practical notations.Footnote 40 Like O crux/ Cruci, Iam/ Iam is found, in a fragmentary state, in Mo 7 (fol. 307v), and in Tu (fol. 6r). It is also preserved in Hu (fol. 120r), now dated to the 1330s and 1340s, LoD (fol. 50v), from late fourteenth-century southern Germany, and Trier, Stadtbibliothek, 322/1994 (fols. 214v–215r), from the Moselle Valley in the early fifteenth century.Footnote 41 In all these manuscripts, the voice part which e. 42 copies as the triplum (Iam novum) is given as the motetus and vice versa. Both upper voice parts, which share much of their music and text through extensive voice exchange, address the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the feast from which the tenor's chant melisma is taken.Footnote 42 While this feast was not included in the selections of prefaces and notated Masses, it was clearly important to the main scribe of e. 42, who copied its gospel on the final folio of the manuscript, just above the ex libris (fol. 143r). The compilers of e. 42 therefore seem to have chosen all four motets in line with their larger liturgical priorities, creating a book in which monophony and polyphony provided them with musical material to celebrate and embellish a series of feasts to which they were especially devoted.

Figure 5. Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fols. 6v–7r, showing the layout of Iam novum sydus/ Iam nubes dissolvitur/ [Solem] and of possible further voice parts. Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

Example 1. Transcription of the tenor of Iam novum sydus/ Iam nubes dissolvitur/ [Solem], from e. 42, fol. 6v.

Iam/ Iam has an unconventional layout across the opening fols. 6v–7r, summarised in Figure 5. As expected, the tenor runs along the bottom stave of fol. 6v, taking up only the left half.Footnote 43 In e. 42's other motets, each upper voice part took up either one column (Ave vivens) or a whole page (Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra and O crux/ Cruci). In Iam/ Iam, however, the first voice (Iam novum) begins at the top of the left-hand column of fol. 6v and then continues onto the right-hand column, finishing on the second line. The next voice (Iam nubes) then takes over, finishing on line five of the left-hand column of fol. 7r.Footnote 44

After the end of Iam/ Iam, some unidentified music remains. Originally, most of fol. 7r contained notation and only the bottom stave of the right-hand column remained empty; only the two final staves of the left-hand column and the first stave of the right-hand column can be deciphered under UV light. The bottom stave of the left-hand column seems to contain a note with the long body of a duplex long, suggesting that this stave might contain a tenor voice. Example 2 is a tentative transcription of this music, comparing it against the closest match I have found: a section of the Annuntiantes tenor used for the Petrus de Cruce motet Aucun ont trouve/ Lonc tens/ Annuntiantes. This tenor melisma is drawn from Omnes de saba, the gradual for Epiphany, a feast afforded a notated preface in e. 42 (fol. 8r). As the stave lines are barely legible, the transcription of the remaining visible music in Example 3 remains provisional, but it cannot be the upper voices for Aucun/Lonc tens. I can only suggest two very preliminary possible solutions. First, the music in Example 3 can fit as an upper voice above the relevant portion of the Annuntiantes tenor, as demonstrated in Example 4. Second, it can also fit as a fourth voice above a passage towards the beginning of Iam/ Iam, as shown in Example 5.Footnote 45 Since it does not fit against the very beginning of Iam/ Iam, this putative fourth voice would have to begin a stave before the currently visible music, taking up staves 5–6 of the left-hand column and staves 1–6 of the right-hand column. Given that both the triplum and motetus of Iam/ Iam also take up eight staves, this theory is attractive, However, it would leave the music on the bottom stave of the left-hand column – which I designate ‘tenor’ – entirely unexplained.

Example 2. Transcription of possible tenor from e. 42, fol. 7r, compared with the Annuntiantes tenor, taken from Aucun ont trouve/ Lonc tens/ Annuntiantes.

Example 3. Transcription of possible upper voice from e. 42, fol. 7r.

Example 4. Upper voice of e. 42 with the Annuntiantes tenor.

Example 5. Upper voice of e. 42 as a fourth voice over the opening of Iam/ Iam/ Solem.

Stylistic characteristics of e. 42 motets

The possibility of a relatively precise chronological orientation for the copying of e. 42 in the first decades of the fourteenth century invites further consideration of the eclectic style of its motets, including their use of rhythm, repetitive structure, discantal style and choice of texts. At one end of e. 42's stylistic range stands O crux/ Cruci (Example 6).Footnote 46 This motet, which also appears in Mo 7 and Tu, displays many of the stylistic characteristics associated with those collections. In all manuscripts, its upper voices use up to two syllabic semibreves per breve, while the version in e. 42 adds six groups of four melismatic semibreves to the motetus. As demonstrated by Catherine A. Bradley, pairs of syllabic semibreves are the expected norm within Mo 7, while four-semibreve groups are occasionally added as standard decorative figures in Tu and other motet manuscripts around 1300.Footnote 47

Example 6. Edition of O crux admirabilis/ Cruci cruci domini/ Portare (e. 42, fols. 5v–6r).

One of O crux/ Cruci's central stylistic concerns is cursus-based repetition: in all versions of this motet, the upper voices playfully reuse material across the four cursus of the portare melisma. For example, the opening of cursus 3 (perfs. 23–26) repeats the material found in the triplum at the beginning of cursus 1 (perfs. 1–4) but splits it between the motetus (perf. 23) and the triplum (perfs. 24–26). Although Iam/ Iam does not survive complete in e. 42, its other manuscript transmissions show it to be likewise concerned with upper-voice repetition determined by tenor cursus.Footnote 48 Its melismatic prelude and systematic voice exchange, however, distinguish it stylistically from O crux/ Cruci, making it reflective of a stylistically defined layer of Mo 7 that has often been considered either as English or as influenced by English style.Footnote 49

The two remaining motets in e. 42, while having some stylistic links with O crux/ Cruci and Iam/ Iam, are markedly simpler propositions. The second motet of the collection, Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra shares some of Iam/ Iam's English connections through the settings of two of its texts, O Jesu per opera and Dulcis Jesu, found in the Worcester fragments.Footnote 50 Unlike Iam/ Iam, however, the music of Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra bears little trace of stereotypical English features, so its English texts were likely transmitted to the continent before its setting in e. 42.

Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra likewise shares surface similarities with O crux/ Cruci. Although it uses cursus-based repetition, as designated by boxes in Example 7, it seems more pragmatic than O crux/ Cruci, with less playful motivic redistribution between voices.Footnote 51 The discantal style of Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra is also very different. Although the relationship between tenor and triplum is governed chiefly by contrary motion, the tenor and motetus move mostly in parallel or similar motion, never using contrary motion in two consecutive perfections. As they are mostly either a fifth or an octave apart, this discant recalls the practices of ‘fifthing’ as described by Sarah Fuller.Footnote 52

Example 7. Edition of Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra/ [Tenor] (e. 42, fols. 4v–5r).

In Ave vivens hostia (Example 8), the discantal relationship between the tenor and each of the upper voices is closer to that of O crux/ Cruci, being largely governed by contrary motion.Footnote 53 Its rhythmic style, however, is very different. While O crux/ Cruci depends on the stratification of different levels of rhythmic movement, Ave vivens has all three parts moving in near rhythmic unison; the only points at which the upper voices’ text declamation diverges are largely caused by notational issues with ligatures. Ave vivens also pays much less attention to structural repetition, with no cursus repeats in the tenor. Instead, the music is lent coherence by the constant circling around the home pitch of F: of the twelve poetic lines, only one does not finish on an F/c sonority of some type (perf. 24). Even when the tenor ends a phrase on c (perfs. 12, 28, 44), the triplum provides the F below to create the home sonority.

Example 8. Edition of Ave vivens hostia/ Ave vivens hostia/ Organum (e. 42, fol. 4r).

One final notable stylistic characteristic emerges from e. 42's two simpler motets. Both Ave vivens and Dulcis Jesu/ Jesu nostra use, in their entirety, pre-existent Latin texts. Such a compositional strategy is relatively uncommon in earlier continental collections of Latin motets.Footnote 54 Within the old corpus of Mo, for example, there are only two motets with pre-existing Latin texts.Footnote 55 Around 1300, writing new music for existing Latin texts seems to have become more common: there are three motets with such texts in Mo Fascicle 7, one in Fascicle 8 and two in the Stockholm fragments recently reported by Bradley.Footnote 56

The stylistic character of e. 42 is therefore eclectic, spanning the rhythmic unison of Ave vivens to the syllabic semibreves of O crux/ Cruci and the melismatic opening of Iam/ Iam. Given the frequent scholarly focus on stylistic change in the early fourteenth century, this manuscript is an important reminder that stylistic taste in this period was deeply heterogeneous. Such eclecticism even emerges as characteristic of a particular type of polyphonic collection from around 1300. Good comparators are the Florence Laudario and the Salzburg fragment reported by Peter Jeffery.Footnote 57 In Florence, there are simple pieces including the two settings of Dulcis Jesu memoria and a motet on the sequence Victime paschali laudes. These sit alongside the widely transmitted motet Amor vincit omnia/ Marie preconio/ [Aptatur], whose triplum uses syllabic semibreves.Footnote 58 In Salzburg, a mensurally notated sequence is copied alongside two complex hockets and a conductus.Footnote 59

Notation

Two of the closest comparands for e. 42's notational strategies are the Salzburg fragment and Hu, which parallel e. 42 in their notation of both ligatures and semibreves. Both manuscripts can be dated to the first half of the fourteenth century, with Jeffery placing the former at the beginning of the century and David Catalunya the latter in the 1330s and 1340s, reinforcing the plausibility of the dating for e. 42 proposed earlier.Footnote 60 The revisions to the notation of e. 42's semibreves especially seem to reflect the unsettled practice for using upstems found in these two manuscripts and provide tantalising hints of the changing conceptualisations of semibreve rhythm in both Italian and French theory at this time. The use of ligatures in e. 42 is additionally paralleled in a series of manuscripts that have a broader and more uncertain set of dates, underlining the long-lived nature of this aspect of e. 42's notational strategies.

Ligatures

Judged against the prescriptions of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century theorists, the e. 42 scribe uses ligatures in an idiosyncratic way, seeming to justify Gallo's claim that the scribe was somewhat lacking in knowledge of mensural notation.Footnote 61 When writing a descending ligature beginning with a breve, the scribe often does not draw a downstem to the left, which would normatively denote a ligature with propriety: in Ave vivens, for example, a ligature without propriety and with perfection frequently denotes two breves (see ligatures in solid circles in Figure 6). Downstems sometimes assign propriety more conventionally, as in the three-breve ligature highlighted with a dashed circle in Figure 6. This inconsistency of ligature shape also occurs in the notated monophonic chant in e. 42, where use of downstems to the left is likewise patchy, further supporting the previous argument that e. 42's polyphonic and monophonic notations were part of the same copying project.Footnote 62 This behaviour cannot be attributed simply to a lack of notational knowledge on the part of the e. 42 scribe, as it is also found also in the Salzburg fragment and in the hockets transmitted by the fragment from Dijon, Bibliothèque municipale, 447.Footnote 63

Figure 6. The treatment of propriety in the ligatures of Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fol. 4r. Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

The e. 42 scribe's preferred method for assigning perfection to both descending and ascending ligatures is a downstem on the final note of the ligature (Figure 7). In Hu, the descending form is used frequently and the ascending one a little less so. Both forms are also found in Exaudi/ Alme deus/ Tenor in the fragment, of uncertain provenance, now in Dijon, Bibliothèque municipale, 35.Footnote 64 Finally, similar notational parallels with LoD, a late fourteenth-century German manuscript that preserves Iam/ Iam alongside other Ars Antiqua repertoire, demonstrate that e. 42's notational strategies for ligatures were clearly long-lived and geographically widespread.Footnote 65

Figure 7. The treatment of perfection in the ligatures of Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fol. 4r. Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

The scribe of e. 42 could show propriety and perfection in more traditional Franconian ways: in the tenor of Ave vivens, for example, numerous ligatures are assigned perfection by placing the final note directly above the penultimate one. The scribe's ligature use is therefore not necessarily best explained by Gallo's diagnosis of ineptitude with mensural practice, but rather as a context-dependent approach guided by particular notational habits. These habits connect e. 42 to a diverse group of sources. Some of these likely originate from a similar period to e. 42, including the Salzburg fragment (early fourteenth century) and Hu (1330s and 1340s). The Salzburg fragment may even originate in relative geographical proximity to e. 42, as Jeffery argues that its text hand has some Italian characteristics before eventually concluding it is most likely from southern France.Footnote 66 Others, especially LoD (late fourteenth-century Germany), demonstrate that this notational behaviour was used in very different temporal and geographical situations.

Semibreves

The notation of semibreves in e. 42 relates it more specifically to sources such as the Salzburg fragment and Hu and helps to support the early fourteenth-century date for e. 42 proposed earlier.Footnote 67 In O crux/ Cruci, dots of division fluently split syllabic semibreves into breve units.Footnote 68 Nine semibreves in this motet, furthermore, bear an upstem. With two exceptions, these stems appear on the first of a group of three semibreves, as in the Salzburg fragment and Hu.Footnote 69 These stems generally support semibreve rhythms which place shorter values near the beginning of the group, a tendency which can be seen in the light of the developments of different theories of semibreve rhythm in Marchettus of Padua's Pomerium and the treatises derived from Philipe de Vitry's Ars vetus et nova.Footnote 70

The stems in e. 42 are the result of notational revision: of the nine stemmed semibreve groups, five are written over an erasure, such as the first group in Figure 8. Someone seems to have erased the original notation, of which UV light reveals no trace, and inserted the stemmed group.Footnote 71 It is harder to be certain about the four stemmed semibreve groups not written over an erasure, such as the second group in Figure 8, but the thin stems may have been added at the same time as the revision of the other groups. As suggested earlier, this revision of semibreves may also have been carried out at the same time as the larger process of musical checking and revision which included the correction of pitch errors and the clarification of text–music relationships.

Figure 8. Two stemmed semibreve groups from Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fol. 5v, the first written over an erasure and the second not written over an erasure. Images used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

The reviser of the semibreves seems to have begun at the beginning of the triplum and worked haphazardly, revising some semibreve groups but not others. The final group over which the reviser's hand lingered was the first four-semibreve group in the motetus. Here, the first three notes of the group were erased and replaced with a stem on the first, while the fourth note was never erased, betraying a lack of certainty as to how to treat four-note groups. There are no stems after this point in the motetus, so this uncertainty may have prompted the reviser to stop work.

The rhythmic signification of e. 42's semibreve groups is not completely clear. As shown in Figure 9, both e. 42 and Hu notate three semibreves that occur in the space of a breve either with a conjunctura of three rhombs or as a three-note ligature with opposite propriety and without perfection; while this latter notation would usually fill up two breves (semibreve–semibreve–breve), these scribes clearly understood it as a flexible sign that could also stand for a single breve.Footnote 72 For Hu, Nicolas Bell has argued that both notations signify three equal minor semibreves.Footnote 73 If the same rhythms applied in e. 42, the stems would merely remind the singer that all three notes were minor semibreves. Jeffery, referring to the usual interpretation of a three-note ligature with opposite propriety, preferred a reading in which the first two notes split up one minor semibreve and the third note was a major semibreve, resulting in one of the two possibilities shown in the second row of Figure 9.Footnote 74

Figure 9. Possible rhythmic interpretations of semibreve groups. Images from Bodleian Library, lat. liturg. e. 42, fol. 5v, used under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. (colour online)

These patterns depend on a ternary division of the breve. The idiosyncrasies of e. 42's notation for O crux/ Cruci, both before and after the revision, are perhaps more easily resolved in duple time, with each breve comprising two equal semibreves. One such idiosyncrasy, which was present before the semibreve revision, is the four-note ligature with two opposite propriety stems (Figure 9).Footnote 75 The Anonymous of St Emmeram begrudgingly allows this shape, understanding it as lasting two breves.Footnote 76 In e. 42, however, it must fit within one breve.Footnote 77 As this ligature graphically splits into two, it could suggest that the breve it fills up is likewise bipartite, comprising two equal semibreves. The ligature could thereby signify either of the two rhythms provided in the lowest row of Figure 9. In this duple time, three-note groups would therefore take on one of the rhythms given in that same row.

These rhythms could be seen in the context of the music theory of Marchettus of Padua, whose relatively contemporary Pomerium codified a system of notation that began to diverge significantly from that advocated by French theory.Footnote 78 In a Marchettian context, the first of the two rhythms given for three-semibreve groups, with the ratio 1:1:2, is much more likely: it fits into the quaternaria division, with both breve and semibreve split into two equal parts.Footnote 79 The latter of the rhythms for three-note groups, with the ratio 1:2:3, is more in line with developments in French theory, with the stemmed note becoming the equivalent of what came to be theorised as the semibrevis minima. This may explain why the reviser went to the effort of erasing and rewriting. The forms they likely erased, either unstemmed groups of rhombs or a three-note ligature with opposite propriety and without perfection, are still used at other points in this motet to signify three semibreves in the time of a breve. It seems unlikely that the reviser would undertake this fiddly procedure unless it was understood to add rhythmic clarity to the forms that were already present.Footnote 80 A reading in which the stem signified a semibrevis minima would even go some way to explaining the two upstems which do not occur on the first of a group of three semibreves. In these two cases, the stem is on the last of a group of three (highlighted by circles in Figure 4). Perhaps the reviser intended these groups to follow the pattern that would become normal for imperfect time in the Vitriacan treatises, with the ratio 3:2:1.Footnote 81 If so, e. 42's version of O crux/ Cruci would provide a witness of both the iambic preference for semibreve pairs found in the Salzburg fragment and other sources and the trochaic preference prevalent in the Vitriacan treatises.Footnote 82

Conclusions and directions for future research

The motets of e. 42, arguably copied in the first decades of the fourteenth century and revised not long afterwards, have much to add to discussions of the motet and indeed polyphony around 1300. They reaffirm the importance of recent scholarly approaches including the increasingly popular ‘whole book’ approaches to manuscripts of polyphony.Footnote 83 They also suggest new directions. As well as providing vital possible evidence for the changes to semibreve rhythm and fleshing out a complex of manuscripts with similar notational styles, e. 42's stylistic eclecticism suggests that future research might fruitfully consider the heterogeneity of styles practised in the early fourteenth century. It could also profitably be directed not towards the monumental edifices of Mo or the interpolated copy of the Roman de Fauvel, but towards the collections of motets either produced as small booklets or entered into larger manuscripts.Footnote 84 In the Italian context, for example, more might be learned from manuscripts such as Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, II.I.212 (olim Banco Rari 19), a lauda manuscript with a modest collection of polyphony, and Oxford, Bodleian, Lyell 72, a processional with motets and sequences.

Future research, e. 42 suggests, must also be open to wide geographical and temporal networks. While closely tied to Biella, this manuscript has a conspicuous number of links to England. As well as one text by an Archbishop of Canterbury (Ave vivens hostia), it has another that is only found elsewhere in the Worcester Fragments (O Jesu per opera) as well as a motet which has been consistently considered English in style (Iam/ Iam); given the extensive cultivation of the Latin motet in English sources, this connection would richly reward further enquiry.Footnote 85 The notational and reportorial parallels of e. 42, however, also connect it to very different places and times. LoD, a late fourteenth-century manuscript from southern Germany, shares both Iam/ Iam and strategies of ligature use with e. 42, suggesting that Ars Antiqua repertory and notation persisted in numerous geographical areas well into the fourteenth century. While Catalunya has recently demonstrated this long tail of the Ars Antiqua in Spain, much could be gained from re-examining sources such as LoD and the early fifteenth-century source Trier 322/1994.Footnote 86 These new examinations of chronology and style may also provide new contexts for the Ars Antiqua survivals in early fifteenth-century Italy; two motets attributed to Hubertus de Salinis, for example, set Ars Antiqua texts to new music.Footnote 87 Among many important lessons, e. 42 therefore suggests that further investigations into a long-lived and widely geographically spread Ars Antiqua may bear much fruit.