No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Rythmes Biologiques, Anxiété, Cognition et Sommeil

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 April 2020

Résumé

Un des aspects essentiels de la cognition chez l’homme est lié à la qualité de son sommeil qui semble conditionner la fonction de mémorisation aussi bien que d’attention. Il est d’ailleurs remarquable de constater que les molécules hypnotiques peuvent avoir des effets différents sur la cognition, de façon peut-être corrélée à leur action sur les differents stades de sommeil et sûrement liée à la persistance de leurs effets sur la vigilance pendant la journée.

Il est désormais classique de différencier l’anxiété généralisée (AG) de la dépression majeure (DM) par la mise en évidence des variations circadiennes marquées sur les plans clinique, polygraphique, hormonal et physiologique dans la dépression alors qu’une non-rythmicité de l’anxiété généralisée est habituellement revendiquée. Certains rythmes peuvent néanmoins être mis en évidence, bien que de façon moins marquée dans cette pathologie. Ainsi, des variations circadiennes sont souvent notées sur le plan clinique, un maximum d’anxiété et d’attaques de panique se produisant l’après-midi et en début de soirée au moment de l’acmé de la courbe de température centrale. De même, certaines particularités sont notables au niveau de l’analyse des enregistrements polygraphiques de sommeil et des niveaux plasmatiques hormonaux.

Un des faits les plus troublants est de constater une certaine symetrie dans l’expression clinique et polygraphique des troubles dans la dépression majeure et l’anxiété généralisee: la DM est classiquement associée à un réveil très douloureux en milieu de nuit et à une désorganisation de la structure polygraphique du sommeil dans la deuxième partie de la nuit, moments où la température centrale après avoir atteint son niveau minimal amorce une remontée. A l’inverse, l’AG est à son maximum en fin d’après-midi et comporte une insomnie de la première partie de la nuit objectivée par un aspect haché du sommeil observable entre le moment du coucher et le milieu de la nuit, période où la temperature centrale est dans une phase descendante.

Certaines anomalies peuvent être également retrouvées aux niveaux physiologique et biologique. Ces ditférentes observations devraient sans doute, dans l’avenir, susciter des recherches chronobiologiques plus nombreuses et influencer les habitudes de prescription.

Summary

Human cognitive performances, including memory and attention, are significantly linked to sleep organisation and rest—activity rhythms. Certainly due to their long acting sedative effects and probably to their influence on sleep patterns, benzodiazepine and barbiturate compounds influence cognition.

In contrast to major depression, generalized anxiety is classically supposed to be independent of any biological rhythms. However, several circadian features can be detected: frequency of insomnia (difficulties in initiating and maintaining sleep during the first part of the night), significant increase in panic attacks during the afternoon and generalized anxiety during the early evening.

Polysomnographic circadian variation analysis leads to a reliable discrimination between major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety, panic attacks, obsessive compulsive disorders).

Otherwise, physiological rhythms provide interesting data since in man, vigor, mood and cognitive performances are positively correlated to core temperature. The worst period of time for depressed patients is the early morning (3 to 5 a.m.), in correlation with the beginning of core temperature increase. On the contrary, a maximum of anxiety is observed in correlation with the beginning of core temperature decline.

In addition, several circadian rhythms concerning alpha and beta adrenergic receptor affinity have been found. These variations are down-regulated (20 to 30%) and delayed (4 to 12 h) by chronic administration of imipramine, MAOI and chronic bright light exposure. Moreover, chronic imipramine administration in rats delays (4 h) benzodiazepine binding in frontal and striatal areas. In the light of these findings, it is amazing to recall that imipramine positively acts on anxiety disorders after a 2-week-delay.

In conclusion, research on anxiety should stress chronobioiogical data and differentiate accordingly the different clinical aspects. On the other hand, practitioners should take in account «chronosemeiological» and «chronopharmacological» aspects before prescribing tranquillizers.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

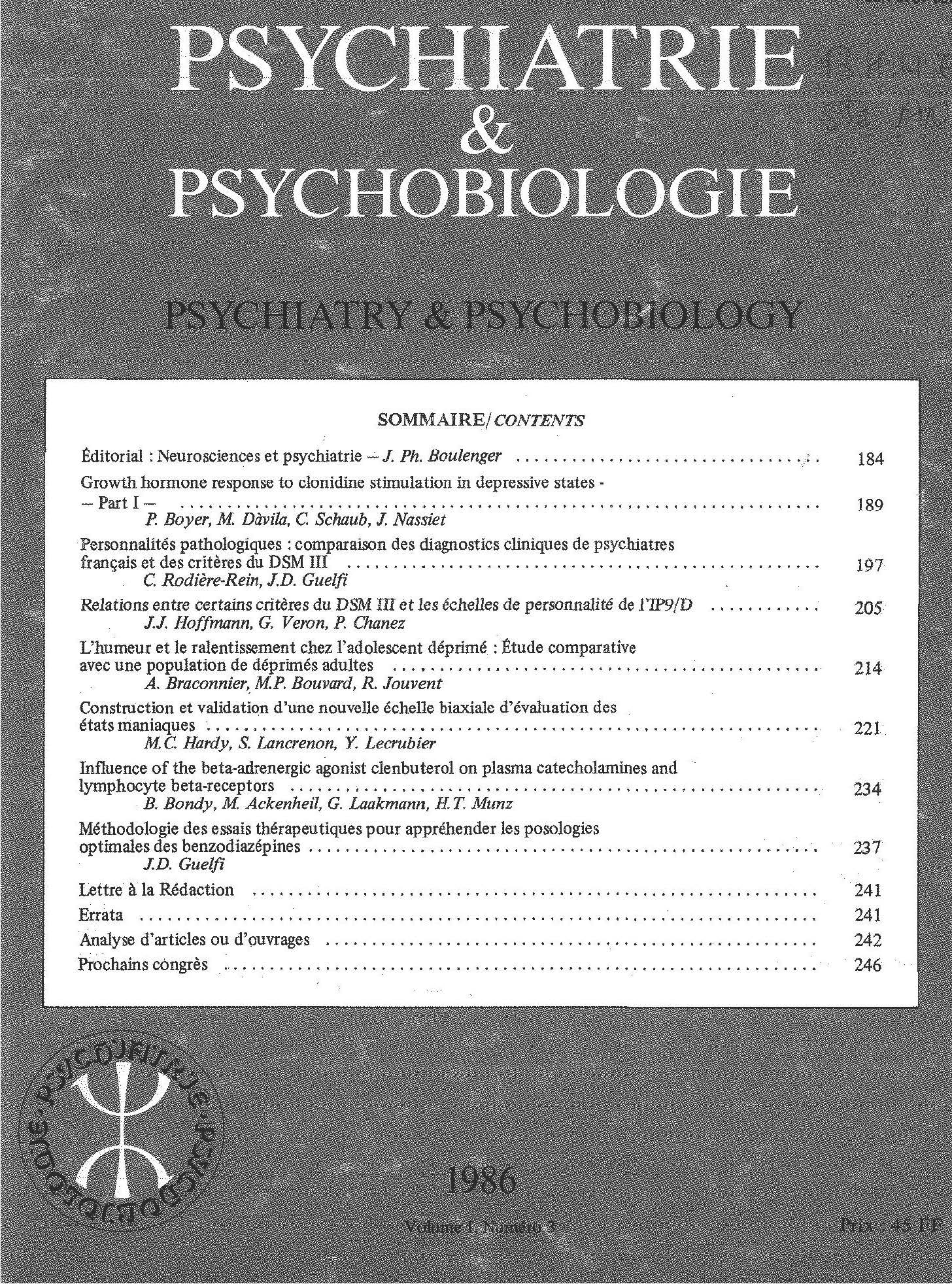

- Psychiatry and Psychobiology , Volume 3 , Issue S2: Aspects cliniques et cognitifs de l'anxiété Paris, 28 Janvier 1988 , 1988 , pp. 167s - 173s

- Copyright

- Copyright © European Psychiatric Association 1988

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.