Introduction

Self-harm refers to any act of intentional self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of level of motivation or suicidal intent (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hall, Simkin, Bale and Bond2003a; NICE, 2022). The prevalence of self-harm has increased globally, with evidence of this in countries such as Norway (Tormoen, Myhre, Walby, Groholt, & Rossow, Reference Tormoen, Myhre, Walby, Groholt and Rossow2020), England (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard, Brugha and Appleby2019), the United States, China, and India (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard, Brugha and Appleby2019; Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape, & Plener, Reference Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape and Plener2012; Tormoen et al., Reference Tormoen, Myhre, Walby, Groholt and Rossow2020). Psychologically, self-harm is associated with low self-esteem, interpersonal difficulties, and hopelessness (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Franklin, Ribeiro, Kleiman, Bentley and Nock2015; Hawton, Saunders, & O'Connor, Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012). Physically, self-harm can result in severe scarring, muscle and nerve damage, infection, and premature death (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012; Witt et al., Reference Witt, Hetrick, Rajaram, Hazell, Taylor Salisbury, Townsend and Hawton2021b). Self-harm is the strongest predictor of suicide (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Ashcroft, Kontopantelis, While, Awenat, Cooper and Webb2017; Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Casey, Bale, Brand, Clements, Farooq and Hawton2019; Hawton, Zahl, & Weatherall, Reference Hawton, Zahl and Weatherall2003b) with approximately 50% of individuals who die by suicide having previous episodes of self-harm (Fazel & Runeson, Reference Fazel and Runeson2020; Foster, Gillespie, & McClelland, Reference Foster, Gillespie and McClelland1997).

Healthcare services have been criticized over their management of self-harm. Studies demonstrate a high degree of variation in self-harm management across general hospital settings (Arensman et al., Reference Arensman, Griffin, Daly, Corcoran, Cassidy and Perry2018; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Steeg, Bennewith, Lowe, Gunnell, House and Kapur2013). For example, the proportion of patient presentations for self-harm receiving psychosocial assessments in emergency departments in England was approximately 58% although it ranged by hospital from 28% to 91% (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Steeg, Gunnell, Webb, Hawton, Bennewith and Kapur2015) despite this being recommended practice for self-harm presentations (NICE, 2022). There is also evidence to support the effectiveness of interventions in preventing repeat self-harm or suicide following a first episode (Witt et al., Reference Witt, Hetrick, Rajaram, Hazell, Taylor Salisbury, Townsend and Hawton2021a, Reference Witt, Hetrick, Rajaram, Hazell, Taylor Salisbury, Townsend and Hawton2021b). Rates of readmission to psychiatric inpatient care for self-harm are highest in the following year, with one third of these occurring in the first month after discharge (Gunnell et al., Reference Gunnell, Hawton, Ho, Evans, O'Connor, Potokar and Kapur2008). Despite this, national guidelines for the short-term management of self-harm have been found to be implemented by healthcare professionals in less than half of the encounters they have with patients (Leather et al., Reference Leather, O'Connor, Quinlivan, Kapur, Campbell and Armitage2020). Together, this evidence highlights a need for improved care for people who self-harm, both in relation to psychosocial assessment and aftercare.

Eliciting patients' attitudes toward services providing interventions for self-harm are essential as they identify barriers to service delivery and influence treatment engagement (Ribeiro Coimbra & Noakes, Reference Ribeiro Coimbra and Noakes2022). The ‘Interpersonal cycle of reinforcement of self-injury’ (Rayner, Allen, & Johnson, Reference Rayner, Allen and Johnson2005) posits that patients' experiences of stigmatizing attitudes from staff and negative therapeutic relationships can feed into negative cognitions about themselves, which can lead to treatment disengagement. Understanding patients' experiences of services therefore enables identification of key areas of improvement to enhance treatment adherence and improve outcomes (Kapur et al., Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen, Hawton and Cooper2013b; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Allen and Johnson2005; Ribeiro Coimbra & Noakes, Reference Ribeiro Coimbra and Noakes2022).

A systematic review of patients' attitudes toward clinical services following self-harm published in 2009 identified predominantly negative perceptions, including poor communication between patients and staff, limited staff knowledge of self-harm and poor therapeutic relationships (Taylor, Hawton, Fortune, & Kapur, Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009). Many patients suggested a need for improvements in psychosocial assessment, referral pathways and access to after-care. As that review was completed over a decade ago and focused only on clinical services, an update of the literature is needed to reflect contemporary practice, widening the scope to the full range of services currently available to people who self-harm. The present systematic review aimed to examine attitudes of patients and their families toward clinical and non-clinical self-harm services from research published since the final search date of the previous review (July 2006). We also aimed to compare patients' experiences of clinical and non-clinical services, defining clinical services as those provided by public or private healthcare providers (primarily consisting of clinicians), and non-clinical services as charitable and voluntary sector organizations, social services, and faith-based organizations.

Method

Our review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Prisma Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). We pre-registered the review protocol with PROSPERO (CRD42021264789).

Search strategy

As our review represented an update of a previous systematic review (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009), we replicated their methodology but expanded our search terms to include clinical and non-clinical services, and updated terminology (supplementary materials: S1).

We searched seven electronic databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Global Health, AMED, HMIC and CINAHL). We also searched Google Scholar and OpenGrey for gray literature. Eligible studies were limited to those in English language and published from July 2006 as the previous review included studies published up until June 2006 (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009). The initial search was conducted in July 2021 and the final search was conducted on 1 July 2022. The reference lists of included studies were hand-searched to identify further eligible studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included published and unpublished primary research studies capturing the experiences or attitudes toward services of people who self-harm. Eligible studies were those that included participants with at least one episode of self-harm, irrespective of suicidal intent. Studies were excluded if participants experienced attempts of assisted suicide, euthanasia attempts or experienced harm without explicit intent (e.g. accidental overdose). We also included studies capturing the attitudes of carers and relatives of individuals who self-harmed. Studies were included if participants received any medical or psychosocial intervention for their self-harm episode from clinical services (primary or secondary healthcare) or non-clinical services (services outside of healthcare settings including but not limited to social, voluntary sector or faith-based services). In order to maximize the evidence, qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies were included, as was the case in the previous review (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009). Secondary analyses of data and systematic reviews were excluded.

Study selection

Search results were exported into Covidence (Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2021) and de-duplicated. All titles and abstracts were first screened by one reviewer (TU). Full text articles of eligible studies were then screened by a second independent reviewer (ZK or GB) using the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions with a third reviewer (SR).

Data extraction

A data extraction table was used to extract information on authors, publication year, country of origin, sample size, sample characteristics (i.e. demographic information), type of self-harm behaviors, type of services and interventions, methodology, measures of attitudes and relevant quantitative and/or qualitative findings. All data were extracted by one reviewer (TU) and a second reviewer (ZK or GB) independently completed data extraction for 25% of articles to compare level of agreement.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fabregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais and Pluye2018) by one reviewer (TU) A second reviewer (ZK or GB) independently conducted quality assessment of 25% of the papers to compare level of agreement. The MMAT has previously been validated for use in systematic reviews and was selected as it is designed to appraise a variety of study designs (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fabregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais and Pluye2018). Calculating an overall quality score is discouraged when using the MMAT, therefore, we reported scores for each criterion. There were high levels of agreement between the reviewers, with only one paper requiring discussion. All studies were given equal value in terms of contributing to the summary findings.

Data synthesis

We summarized quantitative and qualitative findings using a narrative synthesis approach as we anticipated a wide variety of study designs, sample populations and measures and therefore substantial heterogeneity of findings. We used validated guidelines for narrative syntheses from the Economic and Social Research Council framework to follow established practice (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy2006).

One researcher (TU) first grouped studies by methodology, setting and population, tabulating key findings relevant to attitudes toward services using these categories. Team discussions were used to agree these categories. Findings were then compared across studies to categorize similarities and differences in attitudes by setting and population, and to identify meaningful higher-level constructs (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy2006). The final constructs were synthesized following critical discussion with the wider team until complete agreement on structure and content was reached. We have reported findings by age group, highlighting similarities or differences in experiences or attitudes between young people and adults. We have defined ‘young people’ as below 25 years old, as it has been recommended that adolescence should be regarded as continuing to age 24 (Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne, & Patton, Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton2018).

Finally, we sought the perspective of an individual with lived experience of accessing self-harm services to help us interpret findings.

Results

Study selection

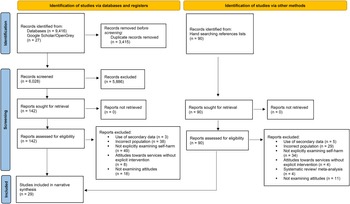

The initial search identified 9443 studies, which was reduced to 6028 studies following deduplication. Full text screening was completed on 142 studies, with 26 studies deemed eligible and included in the review. Three further studies were identified from hand-searching the reference list of these included articles. A total of 29 studies were included (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart describing the study selection process.

Study characteristics

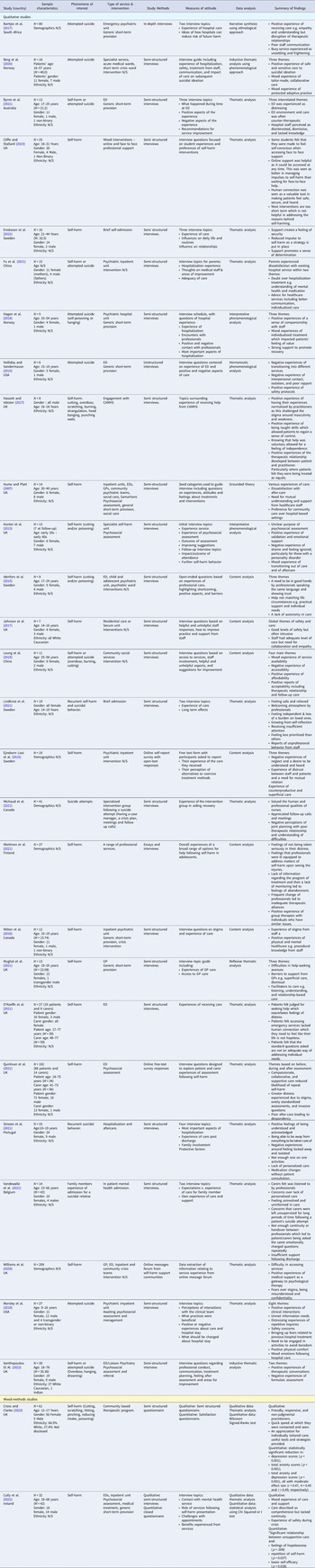

Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Studies were published between 2007 and 2022. However, 27 out of 29 studies were published from 2015 onward. All in high- and middle-income countries. These included 11 studies from the UK, four from Sweden, two from Canada, two from China, two from Norway, two from the USA, one from Australia, one from Belgium, one from Finland, one from Ireland, one from Portugal, and one from South Africa.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

N/S, not specified by authors; N/A, not applicable; M, mean; ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner.

The gender profiles of participants were reported in 24 studies. While one study included only female participants (Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021) and one included only male participants (Hassett & Isbister, Reference Hassett and Isbister2017), all other studies included a mix of female and male participants. Five studies included participants who identified as trans, non-binary and/or gender diverse (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Cliffe & Stallard, Reference Cliffe and Stallard2023; Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy, & Heintzman, Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde, & Chew-Graham, Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham2021; Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit, & Doupnik, Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019). Only three studies reported on participants' ethnicity (Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022; Johnson, Ferguson, & Copley, Reference Johnson, Ferguson and Copley2017; Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas, & McCabe, Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022), all of which included exclusively or majority White participants. The age range of participants was not reported in six studies (Bantjes et al., Reference Bantjes, Nel, Louw, Frenkel, Benjamin and Lewis2017; Ejneborn Looi, Engström, & Sävenstedt, Reference Ejneborn Looi, Engström and Sävenstedt2015; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yang, Liao, Shen, Ou, Li and Chen2021; Michaud, Dorogi, Gilbert, & Bourquin, Reference Michaud, Dorogi, Gilbert and Bourquin2021; Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen, & Aho, Reference Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen and Aho2021; Mitten et al., Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; Williams, Nielsen, & Coulson, Reference Williams, Nielsen and Coulson2020). Eight studies included children and young people only (19 years and under) (Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022; Hassett & Isbister, Reference Hassett and Isbister2017; Holliday & Vandermause, Reference Holliday and Vandermause2015; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Ferguson and Copley2017; Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021; Mitten et al., Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; Simoes, Dos Santos, & Martinho, Reference Simoes, Dos Santos and Martinho2021; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019), three studies included young adults only (18–24 years) (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Idenfors, Kullgren, & Salander Renberg, Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015; Mughal et al., Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham2021) and twelve studies included participants across adulthood (18 years and over) (Berg, Rortveit, Walby, & Aase, Reference Berg, Rortveit, Walby and Aase2020; Cliffe & Stallard, Reference Cliffe and Stallard2023; Cully, Leahy, Shiely, & Arensman, Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig, & Stromberg, Reference Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig and Stromberg2022; Hagen, Knizek, & Hjelmeland, Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Hume & Platt, Reference Hume and Platt2007; Hunter, Chantler, Kapur, & Cooper, Reference Hunter, Chantler, Kapur and Cooper2013; Leung, Chow, Ip, & Yip, Reference Leung, Chow, Ip and Yip2019; O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter, & McCabe, Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022). We have reported findings by age group, highlighting similarities or differences in experiences or attitudes between young people and adults. We have defined ‘young people’ as below 25 years old, as it has been recommended that adolescence should be regarded as continuing to age 24

Overall, the studies examined attitudes of patients/carers following a patient's presentation for self-harm (n = 16), attempted suicide (n = 8) or a mixture of self-harm and attempted suicide (n = 5). Studies examined patients' attitudes or experiences solely (n = 24), relatives' attitudes or experiences solely (n = 2) or both patients' and relatives' attitudes and experiences (n = 3). Studies exclusively examined one type of service (n = 18) or a combination of services (n = 11). The clinical services included in studies were psychiatric/inpatient units (n = 12), emergency departments (EDs; n = 10), primary care (n = 4), secure units (n = 1), crisis wards/brief admission units (n = 3), community-based psychiatric teams (n = 3), community-based crisis care (n = 2), specialist psychiatric wards (n = 1), acute medical wards (n = 1) and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (n = 1). The non-clinical services included in studies were voluntary sector community-based programs (n = 1), social services (n = 2) or a voluntary sector helpline (Samaritans; n = 1). Based on these categories we made a team decision to group findings by clinical v. non-clinical services.

Quality assessment

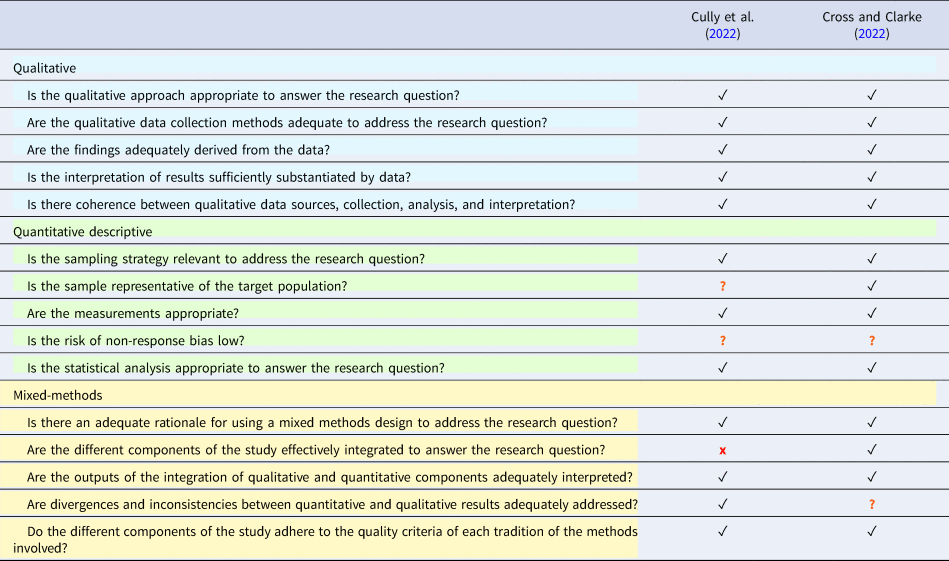

Quality assessment ratings for the studies are presented in Tables 2 and 3. We judged 25 of the 27 qualitative studies to be of high methodological quality. Both the mixed-methods studies were assessed to be of moderate risk of bias.

Table 2. Quality assessment ratings for qualitative studies using the MMAT

✓ = yes, x = no, ? = can't tell.

Table 3. Quality assessment ratings for mixed-methods study using the MMAT

✓ = yes, x = no, ? = can't tell.

Attitudes toward services from individuals who self-harm and their relatives

Our narrative synthesis of studies resulted in the development of four overarching constructs: staff attitudes, therapeutic contact, clinical management, and organizational barriers.

Staff attitudes

Professional stigma

The stigmatizing attitudes of professionals were reported in nine studies that examined clinical services. Across EDs and inpatient units, patients experienced negative judgements, service gate-keeping or belittling comments regarding their injuries (Mitten et al., Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Nielsen and Coulson2020).

Five studies reported a perception that professional stigma acted as a barrier to disclosure, with shame and fear impairing disclosure within psychosocial assessments and when help-seeking (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Chantler, Kapur and Cooper2013; Mitten et al., Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022). Patients reported how their own low self-esteem and self-blame were reinforced by professionals' stigmatizing attitudes (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021).

Experiences of professionals' stigmatizing attitudes varied between clinical and non-clinical services, with the latter preferred for being more accepting. In one study, patients showed preferences for social services and voluntary sector organizations over hospital services, with the former described as more supportive and having the potential to build long-term relationships with patients (Hume & Platt, Reference Hume and Platt2007). In one community-based program, staff (voluntary sector youth workers) were described as non-judgemental and friendly, reducing any shame felt by clients (Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022).

Two studies set in clinical services described perceptions of stigma surrounding mental health diagnoses. Patients highlighted how professionals' interest and compassion diminished after disclosure of a diagnosis of a ‘personality disorder’, with labels of ‘time-waster’ and ‘attention-seeker’ applied (Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). Whilst one UK-based qualitative study reported experiences of staff withdrawal and rushed assessments`(Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Chantler, Kapur and Cooper2013), another UK-based qualitative study reported perceptions of psychiatric diagnoses being wrongfully used by professionals to minimize the severity of a patient's self-harm on the basis it was expected or normalized (Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021).

Young people and adults reported similar experiences of professional stigma, particularly in the ED setting (Mitten et al., Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021).

Minimization of distress

A tendency to minimize patients' distress was reported in nine studies, in samples of young people and adults. Across EDs, GPs and inpatient units, staff were described as uninterested and dismissive of physical and psychosocial distress (Ejneborn Looi et al., Reference Ejneborn Looi, Engström and Sävenstedt2015; Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021; Mughal et al., Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham2021; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022). Three studies set in clinical services reported experiences of staff prioritizing cases that they perceived as more ‘serious’ and patients whose injuries were not self-inflicted, further demonstrating professional discrimination (Ejneborn Looi et al., Reference Ejneborn Looi, Engström and Sävenstedt2015; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yang, Liao, Shen, Ou, Li and Chen2021; Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018). Minimization also resulted in care being withheld; patients were told that pain medication and medical treatments were unnecessary, with staff making comments about a ‘waste’ of beds and resources (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). Minimization led to patients viewing services as ‘cold’ and ‘robotic’, only responding if a ‘threshold’ of seriousness was met (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021).

We noted apparent age differences in findings, in that minimization of distress was more often mentioned in studies of young people (n = 6) than adults (n = 2). It was reported that some GPs treated young people's disclosure of self-harm casually or were dismissive (Mitten et al., Reference Mitten, Preyde, Lewis, Vanderkooy and Heintzman2016; Mughal et al., Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham2021), and young people reported being told ‘it's just a phase’, ‘heaps of young people your age do this, it's normal, you'll get over it when you're’ older’ (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021). In one study, it was said that presentations were taken more seriously when a young person was accompanied by a family member (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021).

Therapeutic contact

Staff-patient relationship

Twenty-one studies presented data describing relationships with staff. Within non-clinical services (social services and voluntary sector services), clients generally described a strong rapport between themselves and staff, based on mutual understanding, non-judgemental care, and trust (Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022; Hume & Platt, Reference Hume and Platt2007; Leung et al., Reference Leung, Chow, Ip and Yip2019). However, experiences within clinical services were variable. Studies reporting positive experiences highlighted genuine and sensitive contact as well as mutual understanding to empower patients and encourage them to collaboratively explore their distress (Cliffe & Stallard, Reference Cliffe and Stallard2023; Enoksson et al., Reference Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig and Stromberg2022; Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Hassett & Isbister, Reference Hassett and Isbister2017; Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021; Michaud et al., Reference Michaud, Dorogi, Gilbert and Bourquin2021; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022). This rapport allowed staff to respond to patients' individual needs for more effective care, such as reacting to fluctuations in suicidality, distress, and instability (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Rortveit, Walby and Aase2020; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019). Positive rapport allowed patients to feel acknowledged as human beings, which instilled hope for recovery (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019).

However, these findings contrasted with reports of superficial contact within clinical services (EDs, inpatient and psychiatric units), whereby patients perceived staff as being disconnected and making little effort to engage with their individual experiences (Bantjes et al., Reference Bantjes, Nel, Louw, Frenkel, Benjamin and Lewis2017; Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Idenfors et al., Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015; Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen and Aho2021; O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Simoes et al., Reference Simoes, Dos Santos and Martinho2021; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019). Three studies highlighted how perceived mistrust from clinical staff impaired patients' feeling of safety and willingness to engage (Ejneborn Looi et al., Reference Ejneborn Looi, Engström and Sävenstedt2015; Holliday & Vandermause, Reference Holliday and Vandermause2015; Hume & Platt, Reference Hume and Platt2007). In one quantitative study, perceptions of unsupportive care were significantly associated with repeat self-harm (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022). Both young people and adults had mixed experiences of staff-patient relationships, and similar views of what good therapeutic relationships looked like.

Relationships with relatives

Relatives of patients also reported negative experiences within EDs and inpatient units, with four studies highlighting their observations of poor communication from staff. Relatives were often excluded from discussions about patients' care, felt inadequately informed about prognosis and had their concerns dismissed (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yang, Liao, Shen, Ou, Li and Chen2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021). Relatives experienced superficial and judgemental staff contact, particularly during sensitive discussions about the patients' care and self-harm. This led to a lack of confidence in staff and doubts over the quality of care (O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). Two studies described similar experiences by young people and adults, whereby carers felt under-involved in decision-making but were overly depended on to keep the person safe (O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021).

Clinical management

Psychosocial assessment

Attitudes toward psychosocial assessments within clinical settings were reported in eleven studies. Assessments were described as superficial, rushed, and formulaic, where generic tick-box questions denied opportunities to explore individual experiences and psychosocial difficulties (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Rortveit, Walby and Aase2020; Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Simoes et al., Reference Simoes, Dos Santos and Martinho2021). While good staff knowledge of psychosocial assessment protocols was reported in EDs and psychiatric wards, knowledge about mental health in those settings was seen as insufficient, with patients recommending staff training to help them better assess the context for and severity of a patient's suicidality (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Holliday & Vandermause, Reference Holliday and Vandermause2015).

Across clinical services, patients and relatives reported a lack of involvement in treatment planning, with unnecessary repetition of questions leading them to believe that staff did not listen or understand their individual experiences (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yang, Liao, Shen, Ou, Li and Chen2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). However, care was positively experienced when staff were sensitive to patients' emotional distress when completing an assessment, collaboratively explored the factors leading to self-harm and involved patients in treatment decisions (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Ferguson and Copley2017; Michaud et al., Reference Michaud, Dorogi, Gilbert and Bourquin2021; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022). We could not compare young people and adults' experiences or attitudes on psychosocial assessment, as we could not separate findings by age group.

Use of restrictions and coercive care

Eleven studies reported variable attitudes toward coercive care in clinical services. In five studies, patients and relatives described the benefits of restrictions and removal of potentially lethal objects to protect against further self-harm (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Rortveit, Walby and Aase2020; Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Hassett & Isbister, Reference Hassett and Isbister2017; Idenfors et al., Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021). Many patients experienced EDs and inpatient wards as ‘safe havens’ that removed them from distressing environments (e.g. difficult home dynamics) meaning patients could effectively shift focus toward recovery (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019). Brief admissions were felt to empower some patients as they felt they were given more control over care through joint decision making (Enoksson et al., Reference Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig and Stromberg2022; Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021). The authors defined these as specialist units where patients had the autonomy to self-refer for brief periods (for example three-day admissions) to manage escalating risk. However, other clinical services such as EDs and more traditional psychiatric inpatient care were experienced more negatively as patients reported feeling disempowered by restrictions (Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Simoes et al., Reference Simoes, Dos Santos and Martinho2021). In light of this, patients and relatives expressed the importance of communicative practice when imposing restrictions: where staff in EDs explained the rationale behind restrictions and used collaborative assessments, these mitigated feelings of anxiety and disempowerment (Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). Similar mixed feelings and experiences toward restrictions and coercive care were described by both young people and adults.

Discharge and aftercare

Negative experiences of discharge following an assessment for self-harm in clinical services were reported across 12 studies. Studies reported how patients felt ill-prepared and unsafe at discharge where feelings of abandonment diminished their trust in clinical services and triggered repeat self-harm (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Rortveit, Walby and Aase2020; Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Hume & Platt, Reference Hume and Platt2007; Idenfors et al., Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015; Xanthopoulou et al., Reference Xanthopoulou, Ryan, Lomas and McCabe2022).

Regarding aftercare, some patients were not contacted by services at all, whilst other patients faced long waiting times (Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Chantler, Kapur and Cooper2013; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). Those who did receive follow-up care were often disappointed due to its brief length, low number of appointments given, and prioritization of discussions about medication over psychology (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Holliday & Vandermause, Reference Holliday and Vandermause2015; Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen and Aho2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021). However, two studies of clinical services investigating experiences of patients on brief admission units described positive accounts of detailed discharge plans and safety planning which provided patients with a sense of security (Enoksson et al., Reference Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig and Stromberg2022; Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021). Greater control over their care meant patients could readjust back into society comfortably (Enoksson et al., Reference Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig and Stromberg2022; Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021). Although the attitudes and experiences of discharge and aftercare were similar between young people and adults, we noted that findings of young people were more focused on concerns about being discharged too early or premature endings in treatment (n = 4) compared to adults (n = 1). Findings with mixed samples of adults and young people, were more focused on dissatisfaction of aftercare (n = 6).

Psychotropic medication

Seven studies reported on attitudes toward medication administration after self-harm, all of which were within clinical services: EDs, inpatient units and community-based psychiatric care. While medication was seen as helpful, staff were perceived to focus more often on describing benefits whilst tending to minimize information on side-effects and risks (Ejneborn Looi et al., Reference Ejneborn Looi, Engström and Sävenstedt2015; Idenfors et al., Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015). Changes in medication without follow-up consultations from staff led patients to view services as negligent (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Simoes et al., Reference Simoes, Dos Santos and Martinho2021). Patients and relatives reported that medication was often administered without adjunctive psychological interventions, which they experienced as avoiding problems rather than an effective resolution (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Yang, Liao, Shen, Ou, Li and Chen2021; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Chantler, Kapur and Cooper2013; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021). Similar experiences and attitudes about psychotropic medication were described by young people and adults. Both groups had a desire for more information about medication side effects (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Knizek and Hjelmeland2018; Idenfors et al., Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015).

Organizational barriers

Waiting times

Nine studies described negative experiences in clinical services of long waiting times across services for young people and adults. For EDs, inpatient and crisis management teams, lengthy waiting times for a psychosocial assessment led to feelings of anxiety, particularly when in busy and loud environments (Bantjes et al., Reference Bantjes, Nel, Louw, Frenkel, Benjamin and Lewis2017; Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen and Aho2021; Quinlivan et al., Reference Quinlivan, Gorman, Littlewood, Monaghan, Barlow, Campbell and Kapur2021; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Nielsen and Coulson2020). Patients and relatives also received little communication regarding the purpose of the wait, reasons for delays and progress (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Vandewalle et al., Reference Vandewalle, Beeckman, Van Hecke, Debyser, Deproost and Verhaeghe2021). Beyond the ED, there were also experiences of long waiting times for aftercare following an initial assessment (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen and Aho2021).

In non-clinical settings, experiences were variable. One community-based program had an average waiting time of 1.7 days between assessment and referral contact, which clients cited as a key reason for high satisfaction (Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022). However, long waiting times within social services were found to heighten client anxiety (Leung et al., Reference Leung, Chow, Ip and Yip2019).

Access to care

Nine studies reported on access to care across clinical services. Young people, adults, patients, and carers, perceived that the broader system was failing individuals who self-harm. They often found themselves limited to crisis support because they face exclusion from services or endure lengthy waiting lists, resulting in a recurring cycle of ED attendance (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; O'Keeffe et al., Reference O'Keeffe, Suzuki, Ryan, Hunter and McCabe2021; Quinlivan et al., 2021, p. 52). EDs, inpatient units and brief admission units were reported as having a lack of beds and staff, which patients felt contributed to excessive waiting times, inappropriate transfers, and premature discharges (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Bellairs-Walsh, Rice, Bendall, Lamblin, Boubis and Robinson2021; Enoksson et al., Reference Enoksson, Hultsjo, Wardig and Stromberg2022; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Ferguson and Copley2017; Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Kaunonen, Kylma, Rissanen and Aho2021). For brief admission, some patients felt the care was less specialized compared to what they would receive in EDs and wanted more options for psychological support (Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021). However, others felt that they could call on staff freely within brief admission wards and also a sense of predictability and safety, unlike in busy and intense EDs (Lindkvist et al., Reference Lindkvist, Westling, Eberhard, Johansson, Rask and Landgren2021).

Many patients were unaware which non-clinical services were available to them and felt that they should be better integrated with clinical services for more accessible care following discharge (Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022; Leung et al., Reference Leung, Chow, Ip and Yip2019). For social and voluntary services, they suggested extended services hours, telephone/digital appointments, and better staffing to improve accessibility (Idenfors et al., Reference Idenfors, Kullgren and Salander Renberg2015; Leung et al., Reference Leung, Chow, Ip and Yip2019; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Nielsen and Coulson2020).

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review of 29 studies examined attitudes toward and experiences of clinical and non-clinical services of individuals who self-harm, as well as the views of their relatives. Our findings relating to clinical services are comparable to those of the previous systematic review (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009) describing negative attitudes toward organizational barriers and clinical management. This suggests little systemic change in clinical service provision for self-harm in the last 16 years. However, our review also included views on non-clinical services, where staff attitudes and therapeutic contact were experienced more positively than in clinical settings.

Patients and relatives reported a lack of individualized and collaborative care within clinical services. This was characterized by superficial and formulaic contact that failed to recognize the complexity of self-harm presentations. These findings may be underpinned by the use of increasingly manualized approach within clinical settings as a means of managing high service demands (Hawton, Lascelles, Pitman, Gilbert, & Silverman, Reference Hawton, Lascelles, Pitman, Gilbert and Silverman2022). Clinical staff themselves have previously reported conflicts between meeting professional regulations and providing holistic care (Bhui, Reference Bhui2016). The only age patterning of constructs we noted were in relation to the minimization of distress, which was more apparent among samples of young people who self-harm; and discharge and aftercare, of which there were more reports of concerns about support ending before young people were ready or felt safe.

Our review highlighted that genuine and sensitive therapeutic contact in clinical and non-clinical services was viewed as a positive experience that patients linked to promoting recovery, a finding which comes as no surprise. Previous research has shown how strong therapeutic rapport enables patients to feel valued and acknowledged, leading to increased self-esteem and reduced self-harm ideation (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Rortveit, Walby and Aase2020; Elliott, Colangelo, & Gelles, Reference Elliott, Colangelo and Gelles2005). One reason why efforts to establish strong therapeutic rapport are not apparently occurring as standard is the stigmatizing beliefs held by some mental health professionals that were also described in our review. Previous research examining staff attitudes in EDs, inpatient and primary care services have revealed stigmatizing beliefs, mistrust in patients, and reduced compassion toward people who self-harm (MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Sampson, Turley, Biddle, Ring, Begley and Evans2020; Rayner, Blackburn, Edward, Stephenson, & Ousey, Reference Rayner, Blackburn, Edward, Stephenson and Ousey2019; Saunders, Hawton, Fortune, & Farrell, Reference Saunders, Hawton, Fortune and Farrell2012; Vistorte et al., Reference Vistorte, Ribeiro, Jaen, Jorge, Evans-Lacko and Mari2018). This difference in attitudes between services may be attributed to a lack of mental health training for staff in primary care, EDs, and other clinical services not traditionally developed for frontline mental healthcare (Caulfield, Vatansever, Lambert, & Van Bortel, Reference Caulfield, Vatansever, Lambert and Van Bortel2019). Our findings demonstrate the importance of specialized training about self-harm and a need for staff support and supervision, to instil positive attitudes, and encourage effective practice and compassion in clinical staff (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Dollman, Jones, Cronin, James, Martinez and Procter2019).

The review also highlighted practical difficulties across services pertaining to waiting times, access, and understaffed services. As this finding is comparable to the findings of the previous systematic review (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009), it suggests that there has been no tangible investment or improvement in ED services over that period. High service demands are another potential explanation for the rushed and superficial care reported. There has been a large increase in self-harm presentations, especially by adolescents, in recent years putting further pressures on services (Gunnell et al., Reference Gunnell, Appleby, Arensman, Hawton, John and Kapur2020; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard, Brugha and Appleby2019). Previous research has highlighted how overwhelmed staff lack the time and resources to provide effective care (Baker & Naidu, Reference Baker and Naidu2021; Mahony, Reference Mahony2014).

Perspective on our findings was provided by an individual with lived experience of accessing self-harm services, which is provided to complement our discussion (supplementary materials: S2). Their perspective is that developments in service provisions over the past 15 years have led to exclusion of those who self-harm, and there is no (or limited) long-term treatment offered to people who self-harm. Psychosocial assessments are often seen as a ‘tick-box’ exercise and do not lead to a concrete treatment plan. They suggest that people with lived experience of self-harm should co-produce training for mental health professionals that is trauma-informed and reduces stigma, particularly for those with personality disorders.

Limitations

Our quality assessment highlighted four studies of low to moderate quality (Bantjes et al., Reference Bantjes, Nel, Louw, Frenkel, Benjamin and Lewis2017; Cross & Clarke, Reference Cross and Clarke2022; Cully et al., Reference Cully, Leahy, Shiely and Arensman2022; Mughal et al., Reference Mughal, Dikomitis, Babatunde and Chew-Graham2021), but we included these with equal weighting to other studies in our synthesis for comprehensiveness. However, we acknowledge that these lower quality studies may potentially have introduced bias. We limited our initial search to studies published in English, which may explain why all included studies were published in high-and middle-income countries. Moreover, only three of the included studies provided information on participant ethnicity, having either a majority or only white-Caucasian participants. Research has demonstrated that Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups experience poor access and quality of care from services due to poor cultural sensitivity and discrimination (Al-Sharifi, Krynicki, & Upthegrove, Reference Al-Sharifi, Krynicki and Upthegrove2015; Memon et al., Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper, Scanlon and de Visser2016). Important attitudes from BAME groups may not have been captured in this review. We differentiated findings by age group where possible. However, we could only do so for 14 out of 29 papers, as the remaining 15 papers had samples of mixed ages that spanned both adolescence and adulthood. This is important considering that self-harm is most prevalent in young people, with both young people and older adults demonstrating high levels of undisclosed self-harm and reduced help-seeking (Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018; Memon et al., Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper, Scanlon and de Visser2016; Troya et al., Reference Troya, Babatunde, Polidano, Bartlam, McCloskey, Dikomitis and Chew-Graham2019). The study by Worsley et al., included individuals as young as nine and isolating their experiences to see how they differ from older adolescents, may have provided useful insights (Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Barrios, Shuter, Pettit and Doupnik2019). Different services are also available for different age groups (e.g. child and adolescent services or adult services), leading to potentially different attitudes. Finally, it was not possible to compare findings by gender. This is important as males have typically been underrepresented in studies focusing on self-harm mental health (Hassett & Isbister, Reference Hassett and Isbister2017), and people identifying as trans, non-binary, and/or gender-diverse are at greater risk of self-harm (Marshall, Claes, Bouman, Witcomb, & Arcelus, Reference Marshall, Claes, Bouman, Witcomb and Arcelus2016). Overall, there is a clear research need to explore attitudes toward services by different demographic groups.

Included studies inconsistently reported on patients' histories of self-harm and clinical management. Therefore, we could not interpret findings in the wider context of patients' previous experiences of services. Similarly, none of the included studies explicitly examined level of suicidal ideation, and the studies examining both attempted suicide and self-harm presentations did not differentiate findings between the two. While in the UK it is customary not to distinguish between episodes on the basis of intent (Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor, & Hawton, Reference Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor and Hawton2013a), it is possible that one-off or frequent attendance for recurrent non-suicidal self-harm elicits a less intense service response than presentations where suicidal intent is expressed, creating different experiences of care. As included studies did not permit us to examine this, there is a need for further research examining how experiences differ by suicidal intent.

Implications

Our findings show that attitudes toward clinical services have shown little improvement in the 16 years since the previous review by a UK-based team (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009). This suggests that the range of UK-based (Department of Health, 2017; NICE, 2013) and international (World Health Organization, 2014) guidelines and policies designed to support service provision have had limited impact. To drive real progress in service provision it may be useful to review guidelines based on these findings. Furthermore, the problems commonly identified by patients (long waiting times, understaffing and limited access to services) have clear implications for the expansion of services, which should be a priority for governments internationally.

With negative staff interactions having a major impact on patient attitudes (Ejneborn Looi et al., Reference Ejneborn Looi, Engström and Sävenstedt2015; Holliday & Vandermause, Reference Holliday and Vandermause2015; Hume & Platt, Reference Hume and Platt2007), policymakers should consider recommendations previously made regarding effective staff training and clinical supervision within clinical services (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur2009). Widespread implementation of training, based on the Self-harm and Suicide Prevention Competence Framework (Leather et al., Reference Leather, O'Connor, Quinlivan, Kapur, Campbell and Armitage2020; National Collaborative Centre for Mental Health, 2018) would provide mental health professionals, clinical managers and service commissioners with guidance for best practice. However, this framework does not seek to prescribe what should be done, but instead there is flexibility in its application that allows for person-centered care (National Collaborative Centre for Mental Health, 2018). Improving staff attitudes and knowledge has been shown to have a wide-scale impact on service quality (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Dollman, Jones, Cronin, James, Martinez and Procter2019). This, in turn, has the potential to improve the therapeutic value of psychosocial assessment and improve outcomes (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Lascelles, Pitman, Gilbert and Silverman2022). It may also reduce costs and pressure on services (Kapur et al., Reference Kapur, Steeg, Webb, Haigh, Bergen, Hawton and Cooper2013b). Our review also highlighted problems with staff interactions viewed as too standardized and superficial. This demonstrates the importance of the therapeutic relationship, whereby staff should build strong rapport with patients and relatives, involve them in treatment decisions and encompass sufficient flexibility in treatments to ensure that practice is person-centered.

This review substantiates the need for integrated services to maintain quality of care during therapeutic contact, discharge, and transitions in treatment. This is of particular importance during repeated service redesign, especially throughout periods in which the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted service provision. With transformations in services and diversions away from EDs toward other primary, community-based, and remote treatments, including mental health crisis hubs, better collaboration between services can promote effective care while reducing service pressure.

Future research

With findings demonstrating little improvement in clinical services in the last 16 years, health service researchers and policymakers should monitor the implementation of service guidelines. Research should also address the large gap in the literature pertaining to the attitudes of under-represented groups including older adults, BAME communities, LGBTQI+ communities and those from low-and middle-income countries. Such groups can offer vital insights that may have not yet been uncovered to broaden our understanding of the quality-of-service provision. Finally, research should evaluate the impact of training and specific service changes on patients and carers' perceptions of services.

Conclusions

The findings of this review provide insights into attitudes of individuals who self-harm and their relatives toward clinical and non-clinical services, which remain largely unchanged since a previous review 16 years ago. Across services, experiences of organizational and clinical management were largely negative, while staff attitudes and therapeutic contact were more positively experienced in non-clinical services compared to clinical services. Our findings have important implications for staff training and practice and should be used to reform existing healthcare guidelines for acceptable care for patients who self-harm.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723002805.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the survivor who commented on the draft and wrote the lived experience commentary. Their insights and perspectives are highly valued, and we are grateful for their advice and support on this paper.

Funding statement

A. P. and S. R. are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) University College London Hospital (UCLH) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). K. H. receives funding from the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

A. P. is a Patron of the Support After Suicide Partnership. K. H. is a member of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England Advisory Group and is a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator (Emeritus).

Ethical standards

Ethical approval not required. All data are in the public domain. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/information/author-instructions/preparing-your-materials.