Introduction

Ernest Roume was born in Marseille in 1858. The son of a merchant, he entered the Council of State (Conseil d’État) after graduating from the École Polytechnique. During his career in the administration, he became Director for External Trade, and Director for Asian affairs at the Ministry for the Colonies. He then held the position of Governor General for the Federation of French West Africa, from 1902 to 1908. After a leave from the administration, he governed Indochina from 1914 to 1917 (Arch. nat., Base de données Léonore, LH//2392/4).

Jules Carde began his career in Algeria, where he had been born in 1872 as the son of a colonial administrator. From 1892 to 1895 he was a clerk, at the very bottom of the colonial administrative hierarchy. He went to Madagascar in 1895, where he slowly climbed the hierarchy until he became a colonial administrator in 1907. He then spent a year in Martinique before being posted in French West Africa. He spent the rest of his career in colonial central administrations, mostly in French Equatorial Africa. He reached the rank of governor in 1916, being given French Congo and later Cameroon. From 1923 to 1930, he was Governor General for French West Africa and then Governor General for Algeria from 1930 to 1935 (Arch. nat., Base de données Léonore, 19800035/60/7418).

What could explain such different careers? Roume was a metropolitan civil servant, with a very high status, as evidenced by the university he attended and his subsequent career, yet he had no colonial experience. Carde’s career was very different: he did not graduate from a prestigious university and began low down in the hierarchy of the colonial administration, with none of the support from his corps that Roume had received.Footnote 1 And yet he reached the most prestigious and powerful post in the empire, the governorship of Algeria. During a 20-year period, from Roume’s governorship of French West Africa to Carde’s, the colonial administration underwent a radical transformation in terms of recruitment. We posit that this transformation reflects the autonomization of the empire as a social space, or at least of its administration.

The article argues that empires are the product of social entities structuring themselves, especially, inside the imperial administration, building on the framework of linked ecologies (Abbott Reference Abbott2005). We analyze the process of professionalization of the governors’ group with respect to other professional groups within the imperial space (ecology) and the French metropolitan ecology. Using data on the career of 637 colonial governors between 1830 and 1960, we examine the variations in the recruitment of these senior civil servants. We rely on the optimal matching technique to distinguish typical sequence models and identify nine common career trajectories that can be grouped into four main clusters. We show that the rise of the colonial cluster during the Interwar period corresponded to the peak of the administrative autonomy in the imperial ecology, which is consistent with the broader history of French colonization. We argue that this autonomy comes from both professional and organizational logics.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section “Professionalization processes in colonial administrations” describes the colonial administration and draws on the literature to explore autonomization processes in colonial administrations. Section “Data and research design” reports data sources and the dataset construction, and the design of the research. Section “The variety of careers” describes the careers of colonial governors and their evolution over time. Section “The social closure of the governor’s corps” proposes a narrative explanation to the closure of the governors’ professional group and the administrative imperial ecology.

Professionalization processes in colonial administrations

Contrary to what the literature on metropolitan administrative elites asserts, colonial positions were far more than a mean of climbing the ladder in the metropolitan administration (e.g., Charle Reference Charle2006). A specific closure process took place within the senior civil service, in which the relationship with the metropole played a crucial role. Our hypothesis is that the autonomy governors attained at one period is crucial to understand the autonomy of the Empire from the metropole.

The autonomy of the empire from the metropole

How does the control of the metropole over the colonial empire proceed? Populations originating from the metropole and living in the empire, the colonizers, can form a distinct social space from both the metropolitan space and the colonized space. They lived apart and formed communities in main colonial cities. Anderson (Reference Anderson2006) shows that nationalist movements originated in the creole populations in early colonial empires. However, the number of European settlers, in the vast majority of colonies of the second French colonial empire, was very low (Etemad Reference Etemad2000). To assess the relationship between colonies and the metropole, one needs to focus on that population.

The literature on empires has tackled this issue in a number of ways. We identified three strands of literature of particular interest. The first formalizes the relationship and helps identifying the locus and instruments of control for the empire. The strand on empire projects looks at the influence of ideas, specifically originating from the metropole. These two strands usually look at single colonies. The third strand tries to expand to empire-wide considerations, drawing on Bourdieu’s theory.

Control from the metropole has been formalized through the agency theory as a principal–agent situation (Adams Reference Adams1996; Norton Reference Norton2014) between the metropole and the body responsible for the sovereignty, being an administrative body or a charter company, in the case of early colonial empires. This version has been partially socialized by Norton (Reference Norton and Erikson2015) who focuses on meaning instead of information in the control exerted over agents and embedding this relationship in a network of other relations. In this article, we build on that perspective, albeit in a context where sovereignty is embedded in the administration, considering the civil servants as central to the autonomy of the empire. That administration, in turn, constituted the core of the empire, a large share of the colonial economy depending on public investments and its consumption (Cogneau et al. Reference Cogneau, Dupraz and Mespé-Somps2021). The colonial administration was very powerful in the colonies because part of the intellectual production came from its ranks (Sibeud Reference Sibeud2002), and it faced no real counter-power in the absence of a true political representation in the colonies (Merle Reference Merle2004).

One strand of the literature specifically analyzes how ideas shape empires, by looking at empire projects (Conklin Reference Conklin1997; Comaroff and Comarroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1992). A difference is made between ideas coming from the metropole, shaping the empire through empire projects, such as colonial law, and the policies actually implemented. These projects were adapted depending on the way in which the colonized were seen (Conklin Reference Conklin1997; Go Reference Go2000), and reflected in the way in which the colonial administrative body was organized (Wilson Reference Wilson2011). Norton (Reference Norton2014) adds an interesting feature to the model, mentioning the cultural foundations of the empire, together with the organizational aspects. He stresses the need for the administration to design-specific categories to be able to deal with certain issues, such as piracy. We argue that one could go even further than large policies and projects, by considering mundane acts as part of empire formation shaping its organization, specifically appointments. These acts confirm the influence of the metropole and associate a career and the related abilities to a posting, and the tasks attached to it. An appointment, in a bureaucracy where people are explicitly appointed because of their skills, or a series of appointments showing a pattern, nourishes the image of an able and legitimate governor.

These approaches share a common focus on the relationship of a single colony or commercial organization operating in a region of the empire together with the metropole. If we want to assess the autonomy of the empire, a larger focus is needed. Go (Reference Go2000) developed the concept of “chains of empire” articulating the two previous perspectives. Struggles take place in different spaces and at different levels: in the metropole and between metropolitan actors and colonial actors. They reflect in the colonial projects. In another attempt to characterize the autonomy of the empire, Steinmetz (Reference Steinmetz2008) shows that one could consider the German colonial empire as a semi-autonomous field, reflecting the struggle between the various metropolitan elites and that colonial policies built on the colonisers’ ethnographic knowledge about a given territory. In other words, they developed a specific capital depending on their position in the metropolitan elite and the colony they governed. This approach centred on senior civil servants with a deep knowledge of the specific territory they governed; a situation that was uncommon in the French Empire. We focus on governors as the link between the colonial administration and the metropole; however, unlike German governors, French governors used to move from one colony to another and sometimes came directly from the metropole or had previously followed another career path in the armed forces or in the private sector. We observe no obvious relationship between their background and the colony they governed. There was no field of colonies in that sense.

With a view to encompassing the whole empire, we shall look at the relationship between an imperial professional group and different social entities in the metropole. Professionalization processes are analyzed as one of the processes involved in the construction of states, particularly in the case of certain occupations such as the civil service or the military (Silberman Reference Silberman1993; Skowronek Reference Skowronek1982). Abbott (Reference Abbott2005) suggests that states are constructed and defined in part in relation to the efforts of emerging professions to establish their own space. We operationalize this idea by looking at the careers of colonial governors and how they were appointed. We argue that the concept of what a good colonial governor should be embodied in these practices rather than in theories about colonial administration, and is thus one of the cultural foundations of the empire (Norton Reference Norton2014). We do not look at colonial administration theories – the projects – but at the acts that shape its organization on a daily basis. We examine acts such the appointment of governors and annual assessment of senior colonial civil servants. These acts create a certain vision of the colonial administration, which is evidenced in the commentaries given in the assessments. By looking at the careers of colonial governors, we refer to literature from the 1970s focused on colonial administrators and governors (Cohen Reference Cohen1973; Gann and Duignan Reference Gann and Duignan1977; Kirk-Greene Reference Kirk-Greene1979), and take a fresh look at the professional logics at play. To assert the autonomy of the empire, we look at the influence of the metropole and metropolitan criteria in those logics.

Colonial administration as an ecology

To analyze careers, we draw on the theory of professions. We argue that the most heuristic way to explain the autonomy achieved by the colonial administration is to look at the social group they formed. We use Abbott’s (Reference Abbott2005) framework, considering colonial governors as a social entity, in this case, a professional group. Entities are occupational groups that try to establish monopolies over specific areas of work by using specialized knowledge – becoming their jurisdictions. These entities are part of ecologies. We apply this approach to the empire, which we consider as an ecology. The imperial ecology consists of numerous entities such as the professional group of colonial administrators, and the entity of colonial businessmen. Such a framework focuses on the relations between entities and invites us to analyze simultaneously the way entities constitute themselves through boundaries and the jurisdictions they establish. From this perspective, we consider the colonial administration as an ecology in the making, with governors as a professional group inside that ecology. We will consider the autonomy of colonial governors both from the other entities in the imperial ecology and another linked ecology, namely the metropolitan ecology containing the metropolitan administration, the political sphere, and the private sector.

The career patterns specific to a certain population are a powerful tool for assessing its emergence as an entity (Abbott Reference Abbott1995). We draw on an approach looking at the careers of individuals to explore the autonomy of the governors’ professional group, building on the literature on career paths (Bühlmann Reference Bühlmann2008; Stovel and Savage Reference Stovel and Savage2006). Abbott (Reference Abbott2005) asserts that the historicality of an occupation consists of the historicality of the individuals practising it. The memory encoded in the careers of its members is what makes up the historicality of a profession. They contain the representations and past practices and experiences that individuals use in their actions. The steps of an individual’s career reveal the entities and ecologies to which he is related. Taken together, the careers of the governors reveal the boundaries between the colonial administration and other entities and ecologies.

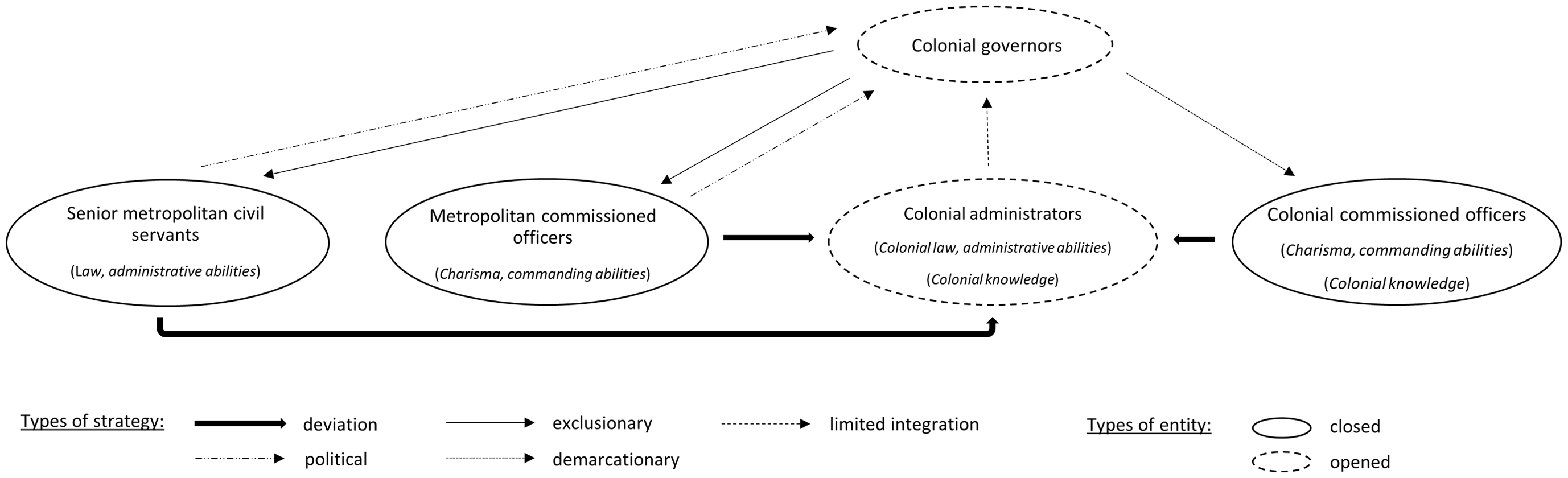

We need to adapt Abbott’s framework to the context of a bureaucracy. Considering organizational dynamics requires an investigation of the recruitment process and the way in which the colonial administration organization influenced governors’ careers. Understanding why one group is favoured over another requires insight into the views of those who recruit its members. We further depart from Abbott’s perspective in a second and more substantial way. The corps of governors, existed from a legal perspective before it existed as a social entity. Initially, the group was only defined in law by the tasks carried out by its members. The group did not have any common history, in the form of historicality, nor was it capable of any kind of collective action. It lacked an esprit de corps. In the literature on professional groups, legal autonomy is the result of a successful closure process when the State recognizes of that closure. Furthermore, governors are defined by their position at the head of the imperial administration: the ecology of the imperial administration is deeply hierarchical, something that is not accounted for in Abbott’s theory. To that effect, we use Witz’s perspective on closure strategies characteristic of dominant occupational groups (Witz Reference Witz1990). Witz differentiates between exclusion strategies and demarcationary strategies. Exclusion strategies “aim for intra-occupational control over the internal affairs of and access to the ranks of a particular occupational group” while demarcationary strategies “aim for inter-occupational control over the affairs of related or adjacent occupations in a division of labour” (Witz Reference Witz1990: 678). To that distinction, we add a third category, taking into account the fact that an occupational group can recruit its members from another group, while maintaining both its domination over the group and a strong boundary with that group. We call “limited integration” the strategy whereby some chosen colonial administrators are integrated into the governors’ corps, making it the most frequent career to reach a governor’s posting, while refraining from making it a guaranteed process. In other words, the limited integration strategy consists, for the individuals of a professional group, in being granted access to a higher rank professional group by being considered as the ‘normal’ career step leading to it. The colonial administrators’ corps succeeded in being considered as the most legitimate career for governing colonies, and thus created a quasi-monopoly over the access to the governors’ corps. The two groups became integrated through the careers of their members. That integration is limited in the sense that although a vast majority of governors were previously colonial administrators, not all colonial administrators became governors. While that strategy may appear an obvious trait of bureaucracies, we shall recall that it was not the only career possible, to become a colonial governor, in particular at the end of the empire. The limited integration strategy excludes people coming from most professional groups bar the one elected. The other entities can oppose a political strategy, seeking their appointment through political patronage, what we label as a “deviation strategy.” They seek access to the highest ranks of the colonial administration through the colonial administrators group that had a less established jurisdiction and a great need for qualified individuals. Figure 1 shows how these strategies apply to the case of the French colonial empire.

Figure 1. The ecologies of the metropolitan and imperial administration.

Note: The colonized people were de facto excluded from the process. Group-specific knowledge and jurisdiction is indicated in parentheses. Reading: Colonial governors used demarcationary strategy to limit the entry of colonial commissioned officers in their group.

French colonial administration and governors

We look at the formation of the French Empire when it emerges from the previous imperial structure, building on Wilson’s idea that modern empires arose against the backdrop and in interaction with their early modern ancestors (Wilson Reference Wilson2011). Its administration was still not stabilized. The second wave of French colonial expansion began with the seizure of Algiers in July 1830. Nevertheless, most of the metropolitan elite showed nothing but indifference to the question of colonization, especially after the Mexican fiasco in 1861. Only after 1871 did the colonial ideology spread among political elites. The rising of the Third Republic and the development of colonial culture were concomitant and led to the establishment of the civilizing mission as the official ideology of the French colonial empire in 1895. By 1900, France had already established a firm control over its 20 or so new colonies (see Annexe 1 in Chambru and Viallet-Thévenin Reference Chambru and Viallet-Thévenin2019). By 1960, only French Somaliland still had a colonial governor. The colonial administration within the French empire was made of two components – leaving aside Algeria which, as a settlement colony, had a very specific role within the empire and relationship with the metropole (Rivet Reference Rivet2002). One component was in Paris with administrative departments dependent on three different ministries. These departments were not very powerful, due to their dispersion, their civil servants’ lack of specialization, and finally, their lack of resources in terms of both manpower and budget (Cohen Reference Cohen1973). The second component was made of administrative departments operating in the colonies. Their organization changed across time, but they were always under the authority of a colonial governor. Colonial governors represented the State in a given territory. The size of the territory could vary, but it had a budget that was autonomous from the rest of the empire. Many former governors sat on the largest colonial firms’ boards and in government committees after they left the colonies. According to Steinmetz (Reference Steinmetz2008) and other historical monographs, they had great influence over the colonies’ government. For instance, Hoisington (Reference Hoisington1995) and Michel (Reference Michel1989) clearly demonstrate how these individuals shaped the polities they governed. We intend to show the professional logics at play. We shall focus on colonial governors as being representative of a larger group of senior colonial civil servants in the colonial administration.

Previous works have shown how, in the British (Kirk-Greene Reference Kirk-Greene2000) and French colonial empires, the colonial administration followed a professionalization process specific to a colony or group of colonies. In the French Empire, graduates from the École coloniale established a gradual monopoly over the colonial service, in particular from 1920.Footnote 2 Their career paths were different to those of the military officers that filled colonial postings at the beginning of the colonization (Cohen Reference Cohen1973) and they sought their legitimacy from a specific knowledge of the colonies, both practical and scientific (Dimier Reference Dimier2004; Fredenucci Reference Fredenucci2003). Colonial administrators generally only reached the position of governor after a long career, two decades on average. These postings also involved very frequent contact with the metropolitan administration and were potentially quite attractive to senior metropolitan civil servants because they were both relatively prestigious and well-paid. We claim that their previous careers give a measure of the autonomy and of the colonial administration’s legitimacy to govern itself.

Data and research design

The individual-level data are from Chambru and Viallet-Thévenin (Reference Chambru and Viallet-Thévenin2019). In this paper, we collected detailed biographical data on the socioeconomic background and the professional careers of every individual appointed at least once as colonial governor between 1830 and 1960.Footnote 3 This data set includes information on 637 colonial governors and covers five colonial federations, 18 colonies, and five protectorates.Footnote 4

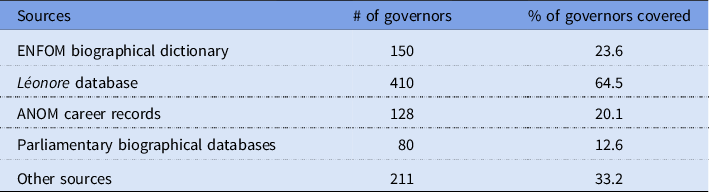

The historiography assumed that most colonial governors came from the ENFOM. We began our collection by using the biographical dictionary for their alumni. The dictionary provides information about each step of alumnis’ career. The dictionary only provided us with information on 150 individuals (Table 1). We then turned to the Léonore database, produced by the French Ministry of Culture, which records all individuals admitted to the Legion of Honour since 1802. People seeking the decoration assembled their professional records and sent them to the selection committee. Among other things, a résumé, a birth certificate, and an employment record are often included. We further supplemented this source with information derived from administrative career records from the Archives nationales d’outre-mer (ANOM), biographical databases of French parliamentarians, and various other sources (Table 1).Footnote 5 If information was not consistent across sources, we gave priority to administrative records over other sources.

Table 1. Sources used for the data set construction

Note: For some governors, we relied on more than one source of information. The cumulative percentage is therefore higher than 100.

For each colonial governor, we collected information on each stage of their professional careers preceding their appointment as colonial governor. At each stage, we collected five pieces of information on the position: the start year, the end year, the geographical location, the organization, and the occupation. To analyze the career pattern of colonial governors, we focused on the organization variable, which provides information on the nature of the structure for which the individual worked. It has the advantage of being more homogeneous and more easily comparable than the occupation variable.Footnote 6

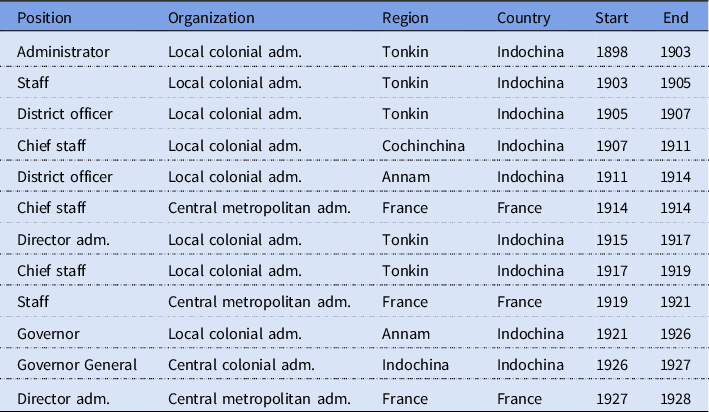

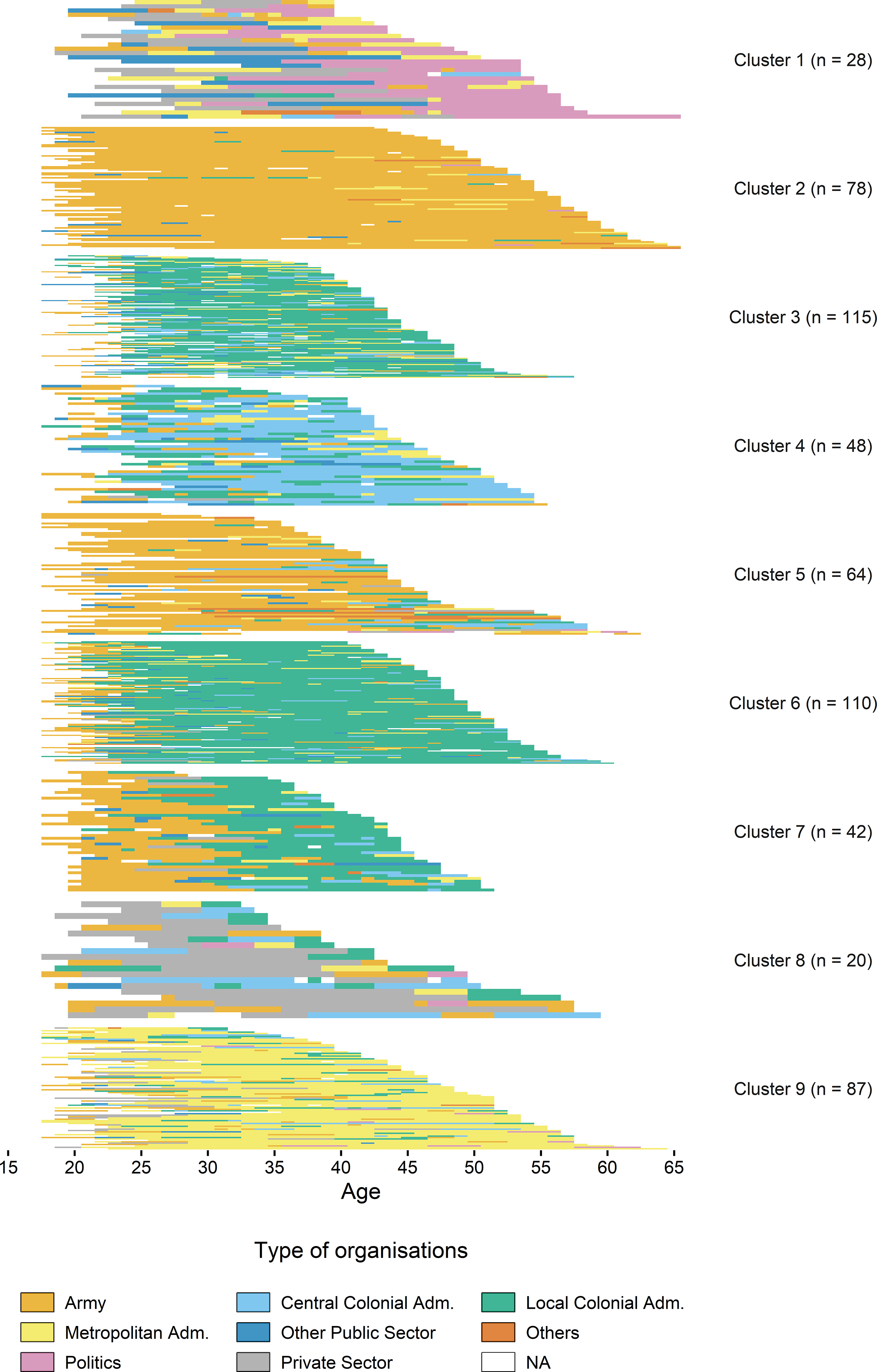

In Online Appendix A.1, we provide the full list of possible categories for the position and the organization variables. In Table 2, we provide an example of our coding strategy using the career of Pierre Pasquier.Footnote 7 If information was missing at one stage of the career, we included the individual in our sample nevertheless, and we encoded the variables as missing. We additionally trimmed each observation on the left at the age of 18. We were unable to retrieve any information for 24 individuals, and we further discarded a further 21 individuals for whom information was too incomplete to constitute coherent sequences.Footnote 8 Overall, the process resulted in the creation of 592 sequences consisting of up to 48 consecutive annual statuses. It should be further noted that most sequences were coded as missing for few years between age of 18 and 25 because individuals were not yet working since they were completing their higher education training (Figure 2).

Table 2. Coding strategy: The career of Pierre Pasquier

Source: Arch. nat., Base de données Léonore, LH//2062/14, notice Pierre Pasquier. https://www.leonore.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/ui/notice/286344.

Figure 2. Distribution of states from age 18 to age 65.

To analyze the sequences, we used the TraMineR package developed by Gabadinho et al. (Reference Gabadinho, Ritschard, Séverin Mueller and Studer2011). We first computed pairwise dissimilarities between our sequences, before performing a dendrogram (hierarchical cluster) analysis to determine the optimal number of clusters (Online Appendix B, Figure B1).Footnote 9 We then added a grouping variable to each observation and plotted the distribution of sequences by cluster to identify patterns in our data and highlight the different professional careers that preceded an appointment as a colonial governor.Footnote 10 Various quality statistics, such as the Calinski-Harabasz index and the Hubert C coefficient, indicate that the optimal number of clusters lays between three and five. We chose a rather high number of clusters, nine, because even if some clusters are relatively similar in terms of sequences, they differ with respect to other characteristics, such as education and maximum rank, that are not observable by the hierarchical clustering algorithm. Therefore, we believe that using only three clusters would result in an overall loss of information and clarity.

To interpret the career dynamics, we used in-depth study of the career records of governors. These records contained their yearly marks and assessments from their superiors, driving directly their careers. We used them to understand the practices and know-how valued in the colonial administration, and what processes led to the emergence of patterns in the governors’ careers.

The variety of careers

Based on indications provided by pairwise comparison and hierarchical clustering (Online Appendix B, Figure B1), we split our data set into nine clusters to analyze the evolution of career of governors. Overall, three main distinct patterns emerged (Figure 2).Footnote 11 Career paths associated with a professional activity in the metropolitan space included three distinct groups. Another three groups could be associated with military careers. Three more groups corresponded to careers in the colonial administration. Tables 3, 4, and 5 contain various group-specific descriptive statistics that enabled us to draw clear distinction between them.

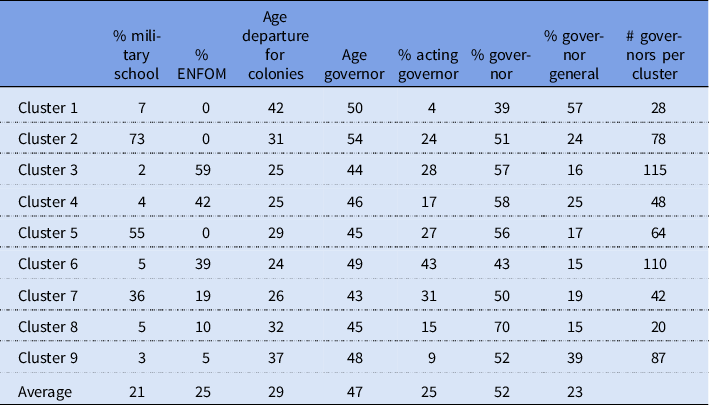

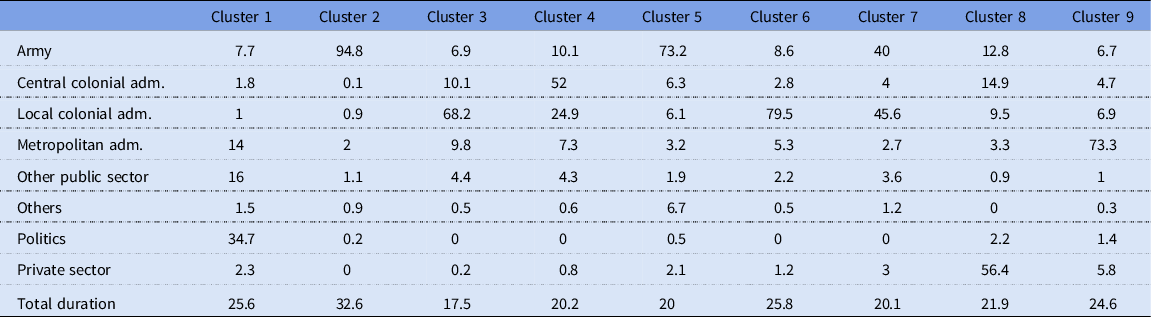

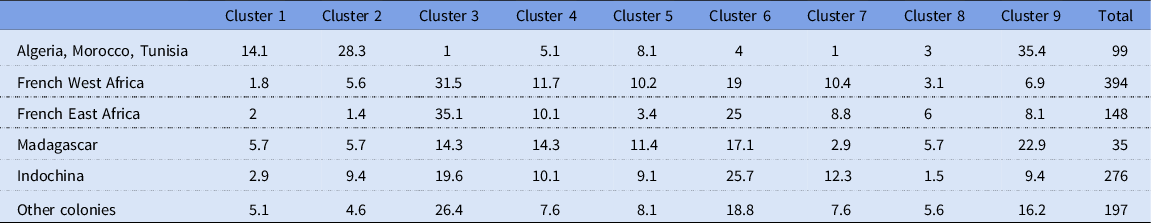

Table 3. Descriptive statistics: Careers of French colonial governors

Note: Descriptive statistics are calculated on a sample of 592 governors. % acting governor, % governor, and % governor general indicate, within each cluster, the highest rank achieved within the colonial administration. Reading: 7 percent of individuals in cluster 1 graduated from a military school. In cluster 1, the highest position reached by 39 percent of individuals was governor. On average, 21 percent of all individuals graduated from a military school and 25 percent graduated from the ENFOM (École coloniale).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics: Sequence characteristics per cluster (in %)

Note: Descriptive statistics are calculated on a sample of 592 governors. Reading: In cluster 2, governors spent on average 94.8 percent of their career in the army. The average duration of professional careers before becoming governor in cluster 2 is 32.6 years.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics: Distribution of colonial governors per cluster per colonial federation (in %)

Note: The total number of governors is 637. Information could not be retrieved for 24 governors, leaving a total of 1,149 positions as colonial governors. Other colonies includes Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, Overseas France, and French Somaliland. Reading: 35.1 percent of individuals who held a position of governor in French East Africa originated from Cluster 3. In total, there were 150 appointments of colonial governors in French East Africa.

Metropolitan careers (I, VIII, and IX)

Individuals included in these clusters were gathered in some of the smallest and least homogeneous groups. They shared a metropolitan career, a relatively late departure for the colonies, and a low rate of acting as governors.

Politicians – I

The 28 individuals in the first cluster spent much of their career as elected representatives. They also spent time in the private sector and in the administration, exclusively in the central administration. They did not have the successful careers of the individuals from cluster IX in the administration, only two of them having held a senior management position. They went to the colonies at the average age of 42, the oldest across all groups. As many as three-fifths reached the position of Governor General during their career. Born in 1833, Paul Bert began his career as a university professor. After a brilliant academic career, he was a member of parliament from 1872 to 1886, with a one-year interruption as Minister for Education. In 1886, at age 53, he was appointed Governor General for Indochina.

Private sector and various administrations – VIII

Cluster IX comprises 20 individuals originating mostly from the private sector, but who also spent some time in various administrations. Similar to other clusters from the metropole, almost all manage to obtain a permanent position during their career (85 percent). Noticeably, when compared with their counterparts, there was a longer period of time between their first departure to the colonies and their first appointment as governors. Born in Paris, de Caix de Saint Aymour became a journalist in 1893 after graduating from the École libre des sciences politiques. He soon traveled across North America and then Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia and later Indochina, Korean, and China (1894–1904) to cover news and write stories about colonization. An active member of the Parti colonial, he continued working as journalist until he joined a parliamentary committee, the Comité d’action française en Syrie, in 1916. Secretary-General of the new protectorate of Syria and Lebanon in 1919, he was appointed governor in 1922 at age 53.

Metropolitan civil servants – IX

The 87 individuals in this cluster spent their whole career in the metropolitan administration before being appointed as governors in the colonies at the average age of 48. Their careers mostly took place in the central administration (89 percent). A large proportion reached prestigious positions, such as that of préfet (31 percent) or senior management positions in the central administration (57 percent). Most of them managed to secure permanent positions as governors during their careers (91 percent). Gaston Cusin became a customs officer, following a family tradition. Born in 1903, his union activities gave him the opportunity to advise ministers from 1936 to 1939 as Deputy Chief of Staff to the Minister for Public Finances Later in the war, he organized smugglers’ networks helping Free French Forces (Forces françaises libres) and took on formal responsibilities in the same organization. In the aftermath of the war, he became a senior civil servant at the Minister for Economy. In 1956, he was appointed High Commissioner for French West Africa for two years.

Military careers (II, V, and VII)

Individuals included in these clusters are gathered in some of the largest and most homogeneous groups. They share a military career.

Military metropolitan and successful commissioned officers – II

The second cluster gathers 78 individuals. They have the longest careers in the population, spent almost exclusively in the armed forces, with sometimes a few years spent in the local colonial administration. They benefited from an early start, often after a military school and about 82 percent rose to the rank of general or admiral. They started their careers in the metropole, gained their first experience in the colonies at the average of 31, and reached the position of governor at age 54, the latest of all groups. Born in Paris, the son of an admiral, Victor Duperré entered the Navy as a ship’s boy in 1840 at the age of 15. He received his first commission in 1846 as a graduate of the naval academy and commanded his first frigate in 1855. He subsequently commanded two navy outposts and became the Chief of Staff of the Minister and a Rear Admiral. He was commissioned Governor of Cochinchina at age 50 in 1875.

Other career commissioned officers – V

Cluster V comprises 64 individuals. A mere 43 percent reached the rank of general or admiral, even though 55 percent graduated from a military school. The group is also less homogeneous than cluster II in terms of geographical trajectories: a quarter spent the entirety of their career in the metropole; a third spent much time in campaigns abroad, but not in the colonial empire; and the rest shared their time between the metropole and the colonies. Henri Canard arrived in Senegal with a cavalry company as a soldier. He was the son of a boatswain, born in 1824 in Rocroy in the Ardennes. From 1847 to 1870, he climbed the hierarchy, becoming a commissioned officer in 1855 and taking command of the cavalry in Senegal in 1863. In 1870, he was appointed chef d’arrondissement, given the task of administrating a small portion of Senegal, because of his knowledge of the country.

He remained in the army during this period and reached the rank of colonel. He was later appointed Governor of Senegal in 1881 thanks to the constant support of his superiors. Because of lack of support in the metropolitan administration, René Servatius (Group IV) replaced him in 1882.

Career officers retrained as colonial administrators – VII

Cluster VII comprises 42 individuals. They began their careers in the armed forces but retrained as colonial administrators after seven or eight years on average. They had less successful careers in the armed forces than their counterparts from cluster V: only 26 percent graduated from a military school and about half were commissioned officers. They decided to embrace the colonial career sooner than their peers did and retrained as colonial administrators after an average of seven to eight years in the army. In the colonial administration, they enjoyed careers similar to those in cluster III, centered on the local colonial administration. The final stages of their careers also looked much like those in cluster III: both reached the position of governor at a relatively young age (43–4 years old) and both have a similar distribution between the highest positions attained. Henri Danel, for example, was the son of a wine merchant born in Béthune in the North of France. He graduated from the École Navale in 1869. He served on many vessels over 15 years before taking an exam and becoming an inspector in the nascent colonial administration. After 8 years of service, he served as Governor of Cochinchina from 1892 to 1895, and then in La Réunion and French Guyana until 1898. At the age of 50, he died during an inspection mission while still in service in Senegal.

Colonial careers (III, IV, and VI)

The three clusters with careers centered on colonial administration differ according to the time spent in the local and central administrations.

Successful local colonial administrators – III

About half of the 115 individuals in cluster III graduated from the ENFOM. They arrived in the colonies at age 25 and spent most of their career in local positions in the colonial administration. Unlike the individuals in cluster VI, only 12 percent began their career as a clerks; many obtained higher ranking positions in the central colonial administration. Overall, they had far more successful careers than their counterparts did in cluster VI: they became governors on average after 19 years of careers and 72 percent secured at least one permanent position as a governor. Camille Bailly was born in 1907 in Amiens. After a Bachelor’s degree in law and a Master’s degree in political economy, he graduated from the ENFOM. He began his career in the local administration in Indochina. In 1940, he became Chief of Staff of the Governor General for Indochina in Saigon. He subsequently spent two years in Cambodia as Chief of Staff to the Governor. He then headed a department at the general governorate for two years. In 1948, he left Indochina, never to return. After one year as a local administrator in Côte d’Ivoire, he became Deputy Governor for Senegal. He was then appointed successively Governor for Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, and French Sudan.

Colonial administrators in central administration – IV

Cluster IV comprises 48 individuals. They spent most of their careers in the central colonial administration with a few years in the metropolitan administration and the local colonial administration. One-third went through staff positions, and 46 percent were secretary generals before becoming governors. Armand Annet, for example, was born in Paris in 1888. He was sent to the colonies in 1911 as a clerk after his military service and a baccalaureate. He joined the staff of the Governor General for French West Africa in 1914, before campaigning in Cameroon as a commissioned officer. In 1917, he was Chief of Staff for the Governor for Moyen-Congo. He then held various staff positions in French West Africa until becoming a Governor for French Somaliland in 1935.

Local colonial administrators – VI

Cluster III comprises 110 individuals whose careers were centred on local colonial positions. They spent their entire careers in the colonies, arriving at an early age (24 years old) after graduating from the ENFOM (39 percent). Overall, about 36 percent began as clerks, the lowest rank in the colonial administration. They usually became governors after long careers (25 years), but almost half were unable to secure a permanent position, the highest rate across all clusters. Only 15 percent ever became Governor General, the lowest rate across all clusters. Frederic Estèbe was born in Argentina in 1863. He was a schoolteacher for six years in France before going to Madagascar as a school teacher. He rose in the ranks of the colonial administration in Madagascar, being given command over larger and larger administrative units until he became mayor of the capital city. In 1911, he was appointed governor for Ubangui-Shari.

The nine clusters differ in terms of professionalization and time spent in the colonies. Some groups follow very established career paths such as those of metropolitan senior civil servants (IX) or military officers (II and V). Some clusters are in between a colonial career and an established career path in the institutions pre-existing to the colonial administration, having experienced a professional bifurcation (cluster VII).

The social closure of the governor’s corps

Three processes participate in the progressive closure of the governor’s professional group. Their interplay can explain the rise of colonial administrators in the ranks of governors and their late fall. The organizational closure of the colonial administration, the emergence of a jurisdiction for colonial administrators, and the evolution of their competitors’ jurisdictions. The following section presents a general narrative for the recruitment process in three phases. It seeks to explain the variations in the prevalence of the groups identified in Section “The variety of careers.”

Organizational closure and demilitarization

Initially, the imperial ecology was strongly linked to the metropolitan ecology and the governor’s professional group depended completely on processes occurring in the metropolitan ecology. The processes affecting the governors’ group and leading to the first step toward its social closure originate from organizational logics.

In 1860, the corps of colonial governors was ruled by the ordonnances organiques (Organic Acts) of August 21, 1825, February 9, 1833, and September 7, 1840 concerning French West Indies, La Réunion and Senegal. It was later expanded to the new colonies. The Président du Conseil (head of government) appointed governors: these appointments did not follow any formal process until they were institutionalized in the 1900s. The colonial administration departments in the metropolitan administration operated under the umbrella of the Ministry for the Navy, with no proper autonomy. Colonial civil servants served under a military status and governors were mainly officers drawn from the colonial units present at the time in the colony. The governors did not constitute a social group different from the corps of officers from the army or the navy. A vast majority of colonial administrators were also military officers. The post of governor was not considered as a step in a colonial administrative career but rather as a short-term secondment from the army or the navy.

Two former governors of Senegal, career officers more invested in the colonial administration than their predecessors, became the advocates of demilitarization of the colonial administration. They made use of the dominant positions they later occupied in the metropolitan ecology. Louis Faidherbe was a commissioned officer in the Armée d’Afrique (occupying Algeria) and a Governor of Senegal between 1854 and 1861 and again in 1863–5. He became général de division, and later a senator. Jean Jauréguiberry was a navy officer and made a great number of stays in the colonies during his career before governing Senegal from 1861 to 1863. He later became an admiral and the Minister for the Navy and the Colonies (1879–80 and then 1882–3). Both of these men believed that governors coming from the armed forces were not qualified and advised not to make appointments that were random or which suited personal convenience where officers would stay a year or two. In 1880, Jauréguiberry put an end to the gouvernement des amiraux of Cochinchina by nominating civil governors and favoring the recruitment of civil colonial administrators. The concerns for governors’ qualifications came with a concern for autonomy from the Undersecretary of State for the colonies, under the authority of the Ministry for the Navy and the Colonies until 1894. The recruitment of a dedicated civilian staff was a way to ensure its autonomy from the Ministry for the Navy.

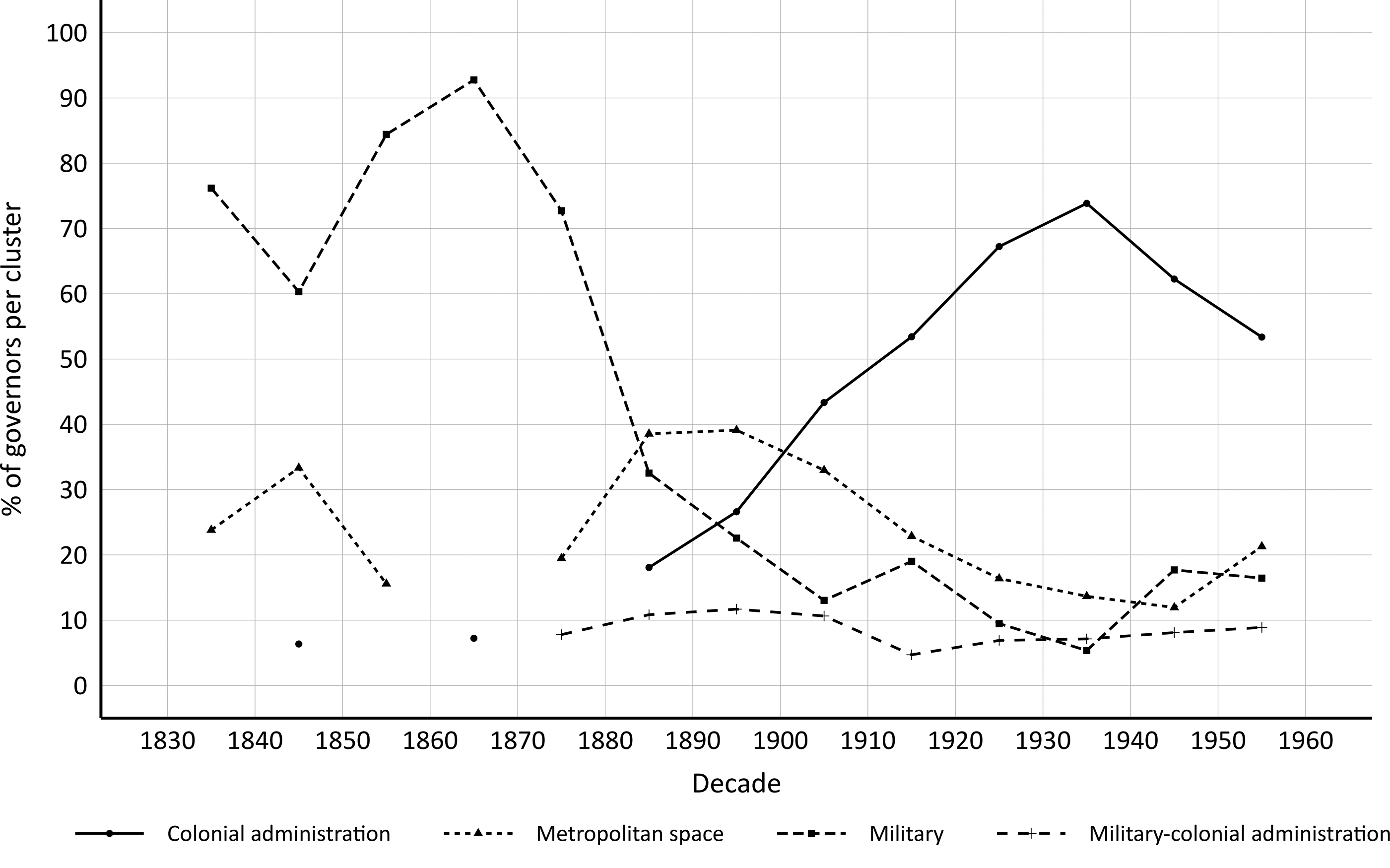

During the 1880s, the empire expanded, with the creation of seven new colonies in Indochina and Africa, and one confederation in Equatorial Africa. At that time, administrative units were created from territories previously under military rule. The colonial conquests being under way, and resistance far from extinguished, the navy focused a lot of its power on the empire. The demilitarization of the administration was implemented by the Department for the Colonies and supported by essayists and publicists to empower the colonial administration in its confrontations with the military hierarchy (d’Andurain Reference d’Andurain2017). Demilitarizing the empire administration was perceived as a way to shift from a policy of conquest to a policy of exploitation. The share of governors who built an entire career in the navy or in the army before taking up a governor’s position decreased rapidly after peaking at 93 percent in the 1860s (Figure 3). The better resilience of the individuals from cluster VII can be explained by their earlier arrival in the colonies and thus their knowledge and ties to the colonial administration. In the absence of a proper colonial administration, metropolitan senior civil servants were thus given the opportunity to rule colonies; hence, the sudden rise in the share of the careers spent in metropolitan administration from 1880 (cluster IX).

Figure 3. Share of governors per group of clusters of career, 1830–1960.

Note: Shares are calculated as the ratio per decade of the number of governors in each group of clusters over the total number of governors. Group of clusters are defined as follows: Colonial administration (clusters III, IV, and VI), Metropolitan ecology (clusters I, VIII, and IX), Military (clusters II and V), Military-Colonial administration (cluster VII). Reading: in 1930, individuals from the group of clusters Colonial administration filled 74 percent of governor positions.

Metropolitan senior civil servants were thus progressively favored over metropolitan officers; the colonial administration differentiated itself from the armed forces, following a strategy of demarcation. During that period, the Department for the Colonies was still not autonomous and the colonial administration in the colonies depended heavily on the metropolitan administration (cluster IX). The governors’ jurisdiction was not well established, and their duties were still changing, in competition with the Ministry for the Navy and the officers commanding the armed forces in the colonies. During this first phase, a differentiation process occurred, separating colonial governors from the commanding officers of the colonial army and the navy. It relied on the emergence of a first boundary separating military and civil posts and careers. The boundary work causing the separation of the colonial administration from the army and the navy is rooted in organizational logics: the Department for the Colonies was made independent of the Ministry for the Navy. These processes took place in the metropolitan ecology; the imperial ecology as such was merely emerging.

Emergence of a proper jurisdiction

Focusing on the recruitment process helps us understand the social closure of the governors’ corps. Until the First World War, the metropolitan administration provided over one-third of all colonial governors (Figure 3). The creation of a specific recruitment process for the colonial administration only dates back to 1887 (Cohen Reference Cohen1973). That transformation happened in parallel to the creation of the Ministry of the Colonies in 1894, after 10 years of unsuccessful attempts. The creation of federations and the position of governor general substantially reinforced the administration in the colonies. Federations were created because of the need to coordinate their development, politically and economically.

Governors general gained substantial autonomy, in particular on issues such as budgets and recruitment policies. Governors-general became involved in the appointment processes and appointed people they knew. A promotion system was implemented, with the direct superior and the governor in charge of the colony marking every senior civil servant every six months. The governor in charge of the colony was the only one who could propose a candidate for a higher rank or post; the minister having only a veto power. Recommendation letters were sent to the ministry to accelerate a promotion or ask for a change of colony, but did not seem to have had a substantial effect. However, the exchanges of letters between governors general and the ministry show the minister chose them after a careful selection by the governor general from the ranks of his senior civil servants. The appointments rarely differed from the proposals. Administrators in chief, the most senior rank in the corps of colonial administrators were subject to very detailed assessments, before being able to access to the corps of colonial governors. Progressively, attention was also given to the appointment of general secretaries, the second in command in a colony. These positions came to be considered as a final step in a career leading to a governorship. Criteria emerged, filtering out military officers with no administrative experience and metropolitan administrators with no experience of the colonies. The judgements exercised in the marking process show how the model for an ideal colonial governor emerged. A jurisdiction arose from the emerging boundaries erected by the successive assessments and appointments. The governors were setting in place a limited integration strategy toward the corps of colonial administrators; while controlling their tasks and careers, they would authorize some of them to be part of their corps.

In that second phase, part of the group of colonial officers progressively merged with the colonial administration. While pursuing a career in the army, they took up administrative postings with increasing responsibilities. Some of them transferred after a few years in the colonial administration, reaching senior postings (cluster VII) and thus following a deviation strategy. The final steps of a career in the army depended much on one’s social capital, a career in the colonial administration was an interesting alternative for the ones with the more modest origins. A porous boundary emerged between the colonial army and the colonial administration. Their knowledge of the colonies was valued, as well as the prestige that their career could reflect on the colonial administration.

Magnifique officier qui a écrit une belle page en AOF et a fait brillamment son devoir pendant la guerre. Administrateur de haut mérite qui remplit avec une rare autorité les fonctions de commissaire (Outstanding commanding officer with an excellent record in French West Africa, performed his duty to the utmost during the war. An administrator with great merit who fulfils the role of commissioner with a rare sense of authority).

Nicolas Gaden, Battalion Commander in the colonial infantry, on secondment in the colonial administration at the time (1917), acting as the commissioner for the governor in Mauritania (ANOM, EE/II/974/1, dossier Nicolas Gaden).

Another boundary thus emerged between metropolitan and colonial administrative careers, through the recruitment of individuals with experience in the colonies. The senior civil servants coming from the metropolitan administration were progressively replaced from the mid-1890s onward by individuals with experience in the management of the colonies (clusters III, IV, VI, and VII). Besides, the colonial administration became more and more common as a career leading to ruling a colony. The posts of general secretary and acting governor became the last steps leading to a governor posting. It became more and more difficult to be appointed directly as a governor: the main exceptions being the general governorship of Indochina and Algeria that retained a certain political character.

The comments on the biannual evaluation sheets valued three different set of skills. Leadership abilities were highly regarded. A warlike vocabulary was often used (commanding capacity, chief, etc.) to describe the attitude of the senior civil servants. In particular, this commanding ability has much to do with how colonial administrators behaved toward the colonized people. In a context where the colonizers were less than 0.1 percent of the total population and had to rely heavily on the colonized, it was expected from the governors to compensate with leadership qualities.Footnote 12

M. Rey a pris le Sénégal en mains avec une maîtrise qui s’est imposée à tous dans sa colonie. Méthodique, précis et volontaire, c’est un Chef par sa personnalité, et un Chef Africain par son expérience nourrie, ordonnée et qui est allée au fonds des choses et des hommes de ce pays (Mr. Rey handled Senegal with a command that imposed itself upon everyone in his colony. Methodical, accurate and pro-active, a leader by nature, and an African leader through his rich, systematic experience that went deep into understanding of the things and people of this country).

The General governor for French West Africa in 1941 about Georges Rey. Born in 1897, Rey graduated from Saint-Cyr, entered the colonial administration in 1925 and became a governor in 1940 (ANOM, EE/II/4108, dossier Georges Rey).

What did it mean to be a leader? Governors and colonial administrators were supposed to personify the presence of the metropole. This included a symbolic equipment, ranging from the white uniform, the residence, the ceremonies dramatizing the power of the metropole and centred on the governor.

Aside from their manners and social skills, senior colonial civil servants were judged upon two distinct fields of expertise: a knowledge of administrative procedures; and a knowledge of ‘the indigenous people’. This shaped the jurisdiction of senior colonial civil servants and helped them draw boundaries with the metropolitan groups and the colonial Army. Marcel Marchesson, born in 1879 entered the colonial administration in 1905 as a clerk. He reached the rank of colonial administrator in 1916, becoming a governor in 1931. Until then, he always held regional commands as a commandant de cercle (district officer). In 1913, his governor noted:

Fera un excellent administrateur lorsqu’il aura perfectionné sa culture générale administrative en servant encore quelques temps en sous ordre dans un chef-lieu de circonscription importante ou mieux, dans un bureau (He will make a fine administrator once he has improved his administrative general culture by serving some more time in a lower-ranking position in a large region, or even better, in the offices of the governor).

(ANOM, Gouvernement G1 AEF C/1209/MARCHESSON).

Jules Brévié symbolizes the most successful colonial career one could achieve. Governor of Niger in 1922, he subsequently governed the Côte d’Ivoire, and became Governor General for French West Africa and finally Indochina. His grading in 1921, while governing the Côte d’Ivoire, noted a high command of the three set of skills expected from governors:

Belle formation administrative, profonde connaissance des milieux indigènes, culture générale, rectitude de jugement, et hautes qualités morales (Good administrative training, profound knowledge of indigenous milieus, good general knowledge, upright in his judgement, and high moral standing).

Born in 1880, Jules Brévié graduated from the ENFOM in 1902 before being appointed as district officer in Haut-Sénégal-Niger in 1902. From April 1942 to March 1943, he was Minister of Ministry for Overseas France and the Colonies (ANOM, EE/II/3718, dossier Jules Brévié).

On the contrary, assessments of those considered not industrious enough and critical of the colonial system are harsh. This was particularly true for civil servants working at the finances’ directorate and the political affairs’ directorate who could possibly reach the rank of governor without ever being a district officer. When an administrator oversees a regional command, the assessments mainly consider their achievements. Until 1945, there were mainly judged from the point of view of the fiscal policy and the political stability of the region. The ideal candidate was a colonial civil servant with experience in both central administration and local administration, respectively, ensuring the quality of his administrative knowledge and his knowledge of the colonized people. It is the rare conjunction of those two set of skills that defined the jurisdiction of governors and set a boundary between the group of administrators and that of governors.

Il a surtout servi dans les cabinets, n’a que 9 mois de service en province, ses connaissances en administration indigène sont donc et ne peuvent être que limitées (He mainly served as an advisor and served only 9 months in a district. His knowledge in colonial administration is and can only be limited).

Joseph Bride started his career as a clerk, the lowest administrative rank, in Indochina in 1895. He never became a permanent governor (ANOM, EE/II/1772/3, dossier Joseph Bride).

The attributes mentioned in the evaluations are the product of the career of their producers and exert a filter on the promotions and nominations to sensible postings. Careers in the colonial administration progressively differentiated between the central and local administrations, hence the later rise of governors originating from clusters III and IV. During this period, colonial administrators shared these prestigious positions with military officers and metropolitan civil servants but also politicians and people coming from the private sector.

Colonial administrators progressively established a quasi-monopoly over the appointment of governors from 1920 to 1940: at its peak, it reached 85 percent of all governors (clusters III, IV, and VI; Figure 3). It became more and more difficult to change paths in the middle of one’s career. Members of the corps progressively controlled the boundary work whereas at the outset, it was mainly the product of external – organizational – forces. Mentions of an esprit de corps appear in the career files, especially about graduates from the ENFOM, or when metropolitan civil servants are appointed in the colonial administration. Yet, during this period, it was harder for a colonial administrator to reach the rank of governor general than it had been between 1880 and 1920. The segmentation inside the colonial administration was mirrored in the governors’ career paths, centred on central administration positions (cluster IV) or local positions (clusters III and VI). At that point, the colonial administration had reached a high degree of autonomy and was headed by people coming from within its ranks. The colonial administrators had established a strong jurisdiction on the government of colonies.

That explanation alone is not sufficient. The appointment of governors being in the hands of the head of State, the Président du Conseil, the recommendations for the governors general could well be ignored. In France, the administration was divided into corps: legal entities that determine one’s career. Some civil servants were part of the so called grands corps that gave access to the highest positions in the State’s administration and wielded considerable power over appointments in the first decades of the twentieth century (Charle Reference Charle2006). Concentrated in the empire, the colonial administrator’s corps did not attain such a reputation and lacked the social prestige of other corps (Cohen Reference Cohen1973). The opportunities given to three corps shed a different light on the governors’ corps. Members of the Inspection Générale des Finances (IGF), one of the most prestigious grands corps found very attractive executive positions in the private sector as soon as the 1880s. Members of the préfectorale, senior representatives of the State at a local level, had many positions at hand in the 1920s. Finally, after the First World War, senior army officers gained access to executive positions in the private sector, and, during the Interwar, had the highest rate of transfer to the private sector of the whole public sector (Charle Reference Charle1987). Successful metropolitan civil servants had other opportunities, both more prestigious and lucrative. They were thus not prone to fight against the exclusion strategy implemented by the governor’s group.

One also needs to look at the relations between the imperial and the metropolitan ecologies. These relations were the product of two processes: the circulation of metropolitan civil servants and army officers between the spaces; and the perception of the empire from the metropolitan administration. During this second period, the idea that the empire had to be developed along lines different from the metropole gained support (Conklin Reference Conklin1997). The success of that idea helped legitimize the colonial administration and reinforce its jurisdiction over the empire. The circulations of metropolitan civil servants decreased because of the opportunities they had in the metropolitan ecology. Finally, the circulations of colonial civil servants to the metropolitan ecology were extremely limited, or forbidden, by their legal status and the idiosyncratic character of the knowledge they had. The success of the closure of their professional group also locked them within the empire. No imperial career, as successful as it might have been, ended in the metropolitan ecology.

Segmentation and partial loss of autonomy

The situation changed from the beginning of the Second World War onward. During this last period, colonial administrators lost ground up to the point in 1960 when they constituted only 50 percent of all colonial governors. The perspective of decolonization and the political changes in the empire in the aftermath of the war prompted the Ministry for the Colonies to appoint senior metropolitan civil servants and army officers that it could trust (clusters II and IX). Many colonial administrators reaching the rank of governor in that period had proven their allegiance to de Gaulle by engaging in the resistance. Confronted with social movements and social demands for institutional and legal changes (Cooper and Stoler Reference Cooper and Stoler1997), the French government appointed governors general politically close to the majority party. They were considered as its direct envoys, conducting governmental policies, whereas they used to be more autonomous. This recruitment policy segmented the corps of colonial governors, with a specialization of those with a previous career in the colonial administration in local affairs.

The change of tasks and the relative convergence of labor and economic policies with the metropole also legitimated a return of metropolitan senior civil servants. The relationships with the colonized and the legal framework converged, although very slowly, toward the metropolitan model, and the economic development of the colonies was planned along similar lines as the metropole. The colonial administration legitimacy drawn from its dealings with the colonized lost recognition. The proportion of colonial governors originating from the colonial administration began its decrease before the Second World War, which is consistent with changes observed in labor policies in the 1930s by Cooper (Reference Cooper1996).

The appointments of former members of the Resistance were also a way to reward them. After France’s liberation, many with little or no administrative experience were nominated as préfets, as a way to politically control the liberated territories. As the political situation stabilized, senior civil servants with a more substantial administrative experience replaced former résistants.

Je dois attirer votre attention sur la nécessité de confier ce territoire politiquement délicat (le Dahomey) à un gouverneur ayant une connaissance de la mentalité et de la politique autochtone (I have to insist on the need to entrust this politically sensitive territory [Dahomey] to a governor with a previous knowledge of indigenous politics and minds).

The Governor General for French West Africa, writing about René Petitbon, former résistant and préfet from 1944 to 1948 and colonial governor from 1949 to 1962 (ANOM, EE/II/5450/PETITBON, dossier René Petitbon).

Some of them made a very gradual transition, from managing a department in the metropole, to managing one of the oldest colonies, converted into departments in 1946, to governing a colony, thus following a successful deviation strategy. But after their first appointment, their careers were not easy in the colonial administration. At some point, René Petitbon was nominated as colonial inspector for French West Africa. In a note to the minister, the governor general voiced his concerns about the nomination: ‘‘Je crois en effet indispensable de vous signaler la réaction de l’administration et du gouverneur qui accepteront difficilement d’être inspectés par un étranger à leur corps’’ (I strongly believe I must inform you of the administration and the governor’s reaction who shall not readily agree to be inspected by someone outside their corps). The governor general wanted someone familiar with the way in which the colony functioned and most of all, someone originally from that administration.

From 1946 onward, the number of colonial postings shrunk. The number of territories under colonial status shrunk with the independence of Lebanon and Syria, and the transition of ‘old colonies’ conquered during the eighteenth century into departments, headed by metropolitan préfets. In addition, from 1945 onward, many colonial administrators operating in Indochina left Asia and were incorporated into the colonial administration elsewhere in the empire. The competition for governor posts became even fiercer. Hence the preferred recruitment of graduated of the ENFOM over people having held junior postings in the colonial administration (clusters III and IV over clusters V and VII). The ENFOM gained during this period a status comparable to the most prestigious French Grandes Écoles in the 1930s (Cohen Reference Cohen1973). Compared with clerks climbing the ladder or metropolitan senior civil servants who transferred to the colonial administration, the ENFOM graduates could rely on recognition of the formal knowledge their training covered. Moreover, they formed a group that recognized and valued its own. Administrators with careers in the local colonial administration progressively lost their access to the governorship.

Il est rompu aux indigènes et administrations de nos territoires africains, tandis qu’il semble peu préparé à l’administration de nos colonies à conseils généraux, et aux luttes électorales (He is very knowledgeable in the ways of the indigenous people and the administration of our territories in Africa, yet he seems ill prepared for the administration of our colonies with an elected body, and election campaigns).

The General Governor for French West Africa about Henri Lejeune in 1917. Lejeune began his career as a rédacteur at the Ministry for War, became a deputy administrator in Algeria in 1895, a General Secretary in 1908, and a Governor in 1917 (ANOM, EE/II/1089/6 et EE/II/3017/10, dossier Henri Lejeune).

Due to the decolonization process, the government preferred to appoint trusted politicians (cluster I), senior civil servants (cluster IX), or individuals from the armed forces (clusters II and V). Moreover, these metropolitans occupied the governor-general positions, with 40 to 71 percent chances of becoming a governor-general compared to colonial governors. A hierarchical differentiation occurred, between the career paths leading to the position of governor and those leading to the position of governor-general. At the same time, colonial administrators were in a difficult position and lost their domination over the territories because of the emergence of engineers from technical departments coming from the metropole on one side and indigenous leaders on the other (Dimier Reference Dimier2004). Those who reached the post of governor were the ones who had obtained a professional legitimacy from their training at the ENFOM.

Conclusion

How does the empire autonomize itself? We argue that the colonial administration is the locus of autonomy in the French colonial empire. We present an argument revolving around imperial professional groups and their autonomy. Specifically, we look at the professionalization of French colonial governors as the basis and evidence of that autonomy.

The autonomy reached by the colonial administration from the 1860s to the 1930s was the product of a process involving multiple steps. Boundaries were progressively erected with other social entities. Colonial governors were first separated from the navy through an organizational process that saw the Ministry for the Colonies become independent. A jurisdiction emerged as a general governorship was created and the recruitment categories specific to the colonial administration were subsequently created. The history of the autonomy of the colonial administration is as much the product of an organizational logic as a professional logic. The politicization of the government of colonies from the 1930s onward altered the autonomy and restricted its professionals to local governments. The relationship of the imperial ecology with the metropolitan ecology was therefore determinative in this last phase. The group of governors appeared as an interface between entities linked to or within the imperial ecology. Governors were a second-order elite to the metropolitan administrative elite; their autonomy was under constant threat from metropolitan groups, especially from the grands corps.

What does this new perspective bring? Rather than looking at specific policies and projects, or at the origins of the ideas shaping the empire (Go Reference Go2000; Norton Reference Norton2014; Wilson Reference Wilson2011), we look at seemingly more mundane and less institutionalized practices than vast concepts such as civilizing mission (Conklin Reference Conklin1997). Empire-wide hiring practices reveal, by the norms they convey, the legitimacy of the colonial administration to provide rulers, and consequently to rule the colonies. These practices involve the building of a category. We argue that such a focus informs us on the specific control over the empire the metropole enjoyed. It also enables to deal with long term and empire wide trends. By putting the emphasis on colonial governors, our argument is that social groups rather than ideas or projects actually structured the empire.

We seek to bring back professional groups in the formation of empires. Linking empire formation and the formation of a specific group can look like a mere expansion on many contributions (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2012) on the formation of the state. Our argument nevertheless goes further. We argue the corps of colonial governors is central to the emergence and therefore, understanding of the French colonial empire, although in its relationship with other entities, such as the metropolitan administration and the imperial administration. Contrary to Bourdieu’s field of State, which emerges in a kind of autonomy, the imperial administrative entity is defined both by hierarchical and organizational relationships with other professional groups. Those relations are the result of a variety of strategies that enrich Witz’s proposition on closure strategies in hierarchical situations. We also show that this group emerges at the level of the empire rather than at the level of one colony.

This paper explores the relationship of the colonial administration with other social spaces, but we must acknowledge one substantial limitation. We did not explore the autonomy of the colonial administration from the economic sphere, mainly because our sources are administrative in nature. We know from other studies that many former governors sat on the board of colonial companies, and governors were under constant pressure from lobbying by colonial firms.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2022.20

Archival sources

Archives nationales (site de Pierrefitte-sur-Seine)

Arch. nat., Base de données Léonore, LH//2392/4, notice Ernest Roume.

Arch. nat., Base de données Léonore, 19800035/60/7418, notice Jules Cardes.

Arch. nat., Base de données Léonore, LH//2062/14, notice Pierre Pasquier.

Archives nationales d’outre-mer (site d’Aix-en-Provence)

ANOM, EE/II/974/1, dossier Nicolas Gaden.

ANOM, EE/II/4108, dossier Georges Rey.

ANOM, Gouvernement G1 AEF C/1209/MARCHESSON.

ANOM, EE/II/3718, dossier Jules Brévié.

ANOM, EE/II/1772/3, dossier Joseph Bride.

ANOM, EE/II/5450/PETITBON, dossier René Petitbon.

ANOM, EE/II/1089/6 et EE/II/3017/10, dossier Henri Lejeune.

Acknowledgments

This article is one of several joint articles by the authors. Author names appear in reverse alphabetical order and reflect a principle of rotation. This paper benefited from helpful feedback and suggestions from Thomas Collas, Sophie Dulucq, Guillaume Favre, Lucine Endelstein, Pierre François, Claire Lemercier, Florence Renucci, and Nathalie Rezzi. We thank participants of “The digital humanities at the service of colonial and post-colonial studies” meeting in Aix-en-Provence and seminar audience at the University of Toulouse 2 for helpful comments.