Morningness-eveningness or circadian preference is an individual difference trait that is related to the sleep-wake cycle and to feelings (affect) in the morning or evening, as well as to performance (cognitive and physical) at different times of the day (Adan et al., Reference Adan, Archer, Hidalgo, Di Milia, Natale and Randler2012). Morningness-Eveningness has a strong biological basis: heritability has been estimated between 20–30% (Klei et al., Reference Klei, Reitz, Miller, Wood, Maendel, Gross and Nimgaonkar2005) and candidate genes have been identified (von Schantz et al., Reference von Schantz, Taporoski, Horimoto, Duarte, Vallada, Krieger and Pereira2015). Further, Thun et al. (Reference Thun, Bjorvatn, Osland, Steen, Sivertsen, Johansen and Pallesen2015) showed that these questionnaires of circadian preferences performed well as validated by actigraphy (e.g., showing correlations about 0.5 with body movement across the circadian rest/activity cycle). Recent research showed that this individual difference is related to many health outcomes and well-being, as well as to personality traits. For example, depression was found to be related to eveningness (Gaspar-Barba et al., Reference Gaspar-Barba, Calati, Cruz-Fuentes, Ontiveros-Uribe, Natale, De Ronchi and Serretti2009), while morningness was associated with higher well-being (Díaz-Morales, Jankowski, Vollmer, & Randler, Reference Díaz-Morales, Jankowski, Vollmer and Randler2013). Concerning personality, especially the Big Five trait of conscientiousness was linked with morningness (Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2010). Health-related behaviors were also found to be associated with morningness-eveningness, and evening oriented people showed a worse health (Merikanto et al., Reference Merikanto, Lahti, Puolijoki, Vanhala, Peltonen, Laatikainen and Partonen2013). Therefore, precisely measuring this individual difference is an important aspect. Just recently, Di Milia, Adan, Natale, and Randler (Reference Di Milia, Adan, Natale and Randler2013) reviewed the psychometric properties of different widely used circadian questionnaires, and suggested that all of them seem reasonably well to be used in scientific research. However, during the last years, many new measures have been developed and this has lead to a significant improvement of the morningness-eveningness scales, which resulted in a new development of a scale labeled MESSi (Morningness-Eveningness-Stability Scale improved; Randler, Díaz-Morales, Rahafar, & Vollmer, Reference Randler, Díaz-Morales, Rahafar and Vollmer2016). The need for these improvements are manifold. First, this new measure evolved out of different existing measures. Second, it integrates the concept of stability or amplitude, which means the range of diurnal fluctuations during the day (Dosseville, Laborde, & Lericollais, Reference Dosseville, Laborde and Lericollais2013; Oginska, Reference Oginska2011), with some people showing higher fluctuations than others do. Third, items should be updated and developments of new items should be reflected in evolving scales. For example, Ottoni, Antoniolli, and Lara (Reference Ottoni, Antoniolli and Lara2011) suggested two questions about energy (energetic feeling) in the morning and in the evening to assess chronotype (Circadian Energy Scale, CIRENS). As many measures are based on wordings of the 1970es, more recent wording might be an improvement to reflect changes in language. Fourth, these previous questionnaires retain clock times, for example the Morningness-Eveningness-Questionnaire (MEQ; Horne & Östberg, Reference Horne and Östberg1976), the Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM; Smith, Reilly, & Midkiff, Reference Smith, Reilly and Midkiff1989) or comparisons with peers/family members as in the Preference Scale (PS; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Folkard, Schmieder, Parra, Spelten, Almiral and Tisak2002). Fifth, in most scales, there is a bias towards morning items, thus a new development should contain a similar number of items referring to morningness and eveningness (and, logically to the new concept of distinctness/amplitude). Sixth, the scoring was not balanced since some items were coded 1–4 on Likert scale and some 1–5. Also, a more technical aspect is the length of the questionnaire. For example, the MEQ contains 19 items and the CSM 13, both without a clear factor structure, while the improved MESS contains 15 items with a clear structure in the original German sample. Further aspects and a detailed discussion of the scale can be found in Randler et al. (Reference Randler, Díaz-Morales, Rahafar and Vollmer2016).

The aim of the present study was to adapt the Morningness-Eveningness-Stability-Scale improved (MESSi) to Spanish population and testing preliminary psychometric properties. More specifically, the objectives were to analyze the factor structure and construct validity of the scale by studying the correlations between morning affect (MA), eveningness (EV) and distinctness (DI) with sleep habits, positive and negative affect, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness to experience personality traits, and subjective alert level across the day.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 261 adults (65% women) between 18–65 years (M = 31.4, SD = 12.01). Regarding family status, the 60.5 % were single, 35.6% were in a relation (married or partner), and 3.9% were divorced. The 36% of couples lived together and the 28.1% had children. Self-reported socioeconomic status was low-middle (60.3%) and middle-high (39.7%). Study level was primary (10.6%), secondary (40.6%), university (38.5%) and post-university (master or doctoral studies, 10.2%).

Variables and instruments

Morningness-Eveningness

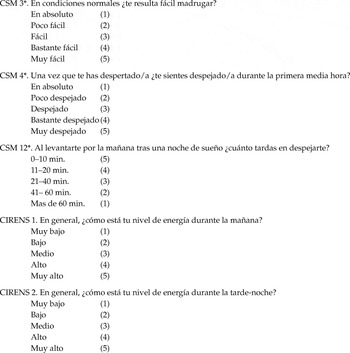

The Morningness-Eveningness-Stability-Scale improved (MESSi; Randler et al., Reference Randler, Díaz-Morales, Rahafar and Vollmer2016) was used as an improved measure of morningness-eveningness trait composed by selected items of CSM (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Reilly and Midkiff1989), Caen Chronotype Questionnaire (CCQ; Dosseville et al., Reference Dosseville, Laborde and Lericollais2013) and Circadian Energy Scale (CIRENS; Ottoni et al., Reference Ottoni, Antoniolli and Lara2011). Three sub-scales were obtained by exploratory, confirmatory factor analysis and external validity analysis: Morning Affect (MA), which was composed by items 3, 4 and 12 of CSM, item 4 of CCQ and morning level of energy from CIRENS. Eveningness (EV), composed by revised item 13 of CSM (evening reformulated), revised items 2 and 11 of CCQ (evening reformulated), item 5 of CCQ and evening level of energy of CIRENS. Finally, Distinctness (DI) was composed by items 6, 8, 10, 14 and 15 of CCQ.

Morningness-Eveningness

The Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Reilly and Midkiff1989) consists of 13 questions about the time individuals get up and go to bed, preferred times for physical and mental activity, and subjective alertness. Five of the elements of the scale refer to different times of day. Given that items are rated on a 4- or 5-point Likert scale, all items of the scale was coded from 1–5 adding one option plus to three items of the CSM. In consequence the sum score is between 13 and 65 and is not comparable to previous studies. Higher values reflect a higher morningness. The Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was 0.88 (inter-item correlation range from 0.23 to 0.66).

Sleep habits

Specific questions were: “What time do you usually go to bed on weekends?” and “What time do you usually wake up on weekends?” Midsleep on weekends was calculated as follows: bedtime + the half of sleep length on weekends. Middle point of time in bed (the midpoint between bedtime and rising time), which is a proxy for MSF (the midpoint between sleep onset and waking) was used (Roenneberg, Wirz-Justice, & Merrows, Reference Roenneberg, Wirz-Justice and Merrows2003). Higher scores in MSF indicate a delay of sleep-wake rhythm.

Personality

Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003) was used as measure of Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability and Openness to Experience. Two items are used as measure of each trait. Each item consists of two descriptors, separated by a comma, using the common stem, “I see myself as...”. Each of the five items was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The TIPI takes about a minute to complete. Although somewhat inferior to the standard longer Big-Five instruments, adequate convergent and discriminant validity, test-retest reliability, and convergence between self- and observer ratings have been supported (Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003). The TIPI can stand as reasonable proxy for longer Big-Five instruments, especially when the framework of relationship has been well established and the focus is on confirm relations between the Big-Five dimensions and other constructs previously established.

Affect

The short-form of the positive and negative affect (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) proposed by Thompson (Reference Thompson2007) was used. Positive Affect (PA) was composed by determined, attentive, alert, inspired and active items, whereas Negative Affect (NA) was composed by afraid, nervous, upset, ashamed and hostile items. Selected items were chosen from the Spanish translation by López-Gómez, Hervás, and Vázquez (Reference López-Gómez, Hervás and Vázquez2015). In the present sample, PA and NA’s Cronbach alphas were 0.83 and 0.69, respectively.

Subjective alertness level

Participants had to estimate how alert they felt on a day when they had no important responsibilities. Ratings were provided at 2-hour intervals, from 6:00 until 2:00, on a 9-point Likert-type scale (higher scores indicated a higher level of alertness). Subjective alertness is probably the most powerful and repeatable of all the circadian rhythms of psychological process (Natale & Cicogna 1996: 491) and it has been used as the best criterion of external validity M/E (Bohle, Tilley, & Brown, Reference Bohle, Tilley and Brown2001).

Procedure and data analysis

Adult participants were encouraged to voluntary participate on the research conducted online. Data were collected between October 2015 and December 2016. Sample size was calculated taking into account the recommended 10:1 ratio of number of participants to number of test items (Kline, Reference Kline and Kenny1998). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) approach was carried out in order to test factorial structure of MESSi. The model fit was evaluated via the χ2 goodness-of-fit test, incremental fit indices, parsimony indices, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Steiger (Reference Steiger2007) summarizes the acceptable levels of some fit indexes: RMSEA values close to .06 indicate acceptable fit, values in the range of .08 to .10 indicate mediocre fit and above .10 indicate poor fit. Comparative fit index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI) and Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) values of .90 and higher than .95 indicated good and excellent model fit, respectively (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). SPSS 22 and LISREL 8.51 statistical programs were used.

Results

Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) of MESSi indicated mediocre fit, χ2 = 304.5, df = 87, RMSEA = .098 (0.086–0.11), CFI = 0.89, NFI = 0.84, GFI = 0.86. However, modification index indicated high correlated error covariances between items 14 and 15 of CCQ. Correlated errors represent shared variance between two items that is not accounted for by the latent factor. When correlated errors exist, they either may be modeled statistically to improve model fit. In the current sample, the largest modification indices were produced by pairs of items within the same subscale that shared similar wording and item. The error covariance between both items was allowed and the fit of three-factor model improved to acceptable level, χ2 = 202.85, df = 86, RMSEA = .072 (0.059–0.085), CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.90, GFI = 0.91.

Alpha coefficients of the three factors were satisfactory. The alpha coefficient of MESSi subscales was as follow: MA = 0.85 (inter-item correlation range from 0.59 to 0.79), EV = 0.83 (inter-item correlation range from 0.45 to 0.82) and DI = 0.72 (inter-item correlation range from 0.28 to 0.55).

In order to test normality of all frequency distributions, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated that empirical distributions of MA and EV were slightly different from a normal distribution (Z = 1.40, p = .038 and Z = 1.49, p = .024, respectively) whereas DI was not different from normal distribution (Z = 0.97, p = .30). However, the frequency distribution of three scales did not show skewness (MA = –1.22; EV = 0.47; DI = –0.46).

The relation between MA and EV was higher than the relation between MA and DI. The pattern of correlations between MESSi and sleep habits was in the predicted direction (see Table 1). MA was strongly negatively related with rise time during the weekend (r = –.44), and also negatively with rise time during the weekday (r = –.22). EV was strongly positively related with bed times (weekend and weekday, .42 and .45, respectively) and Midpoint Sleep Free Days (r = .41).

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations and Pearson Correlations Coefficients between Morning Affect (MA), Eveningness (EV) and Distinctness (DI), and Sleep Habits

Note: n = 261; *p < .05, **p < .001.

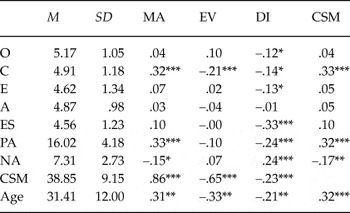

Regarding the relationship between MESSi and personality traits (Table 2), the results indicated that conscientiousness was positively related to MA (moderate size effect) and negatively to EV and DI (low size effect). Interestingly, DI was negatively related to Emotional Stability (moderated size effect), Openness and Extraversion (low size effect). Concerning affect, MA was positively related with PA and negatively with NA. The opposite was found with DI. DI was negatively related with PA and positively with NA. CSM scores were positively related with conscientiousness, PA and age, and negatively related with NA. Finally, age was positive related with MA and CSM, and negatively related with EV and DI.

Table 2. Pearson Correlations Coefficients between Morning Affect (MA), Eveningness (EV) and Distinctness (DI), Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM), personality traits and positive (PA) and negative affect (NA)

Note: n = 261; *p < .05, **p < .01; ***p < .001 O-Openness to Experience, E-Extraversion; C-Conscientiousness; A-Agreeableness; ES-Emotional Stability.

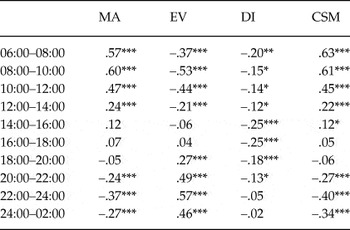

Further, the subjective alertness rating during the day showed that MA was positively related to alertness in the morning, and negatively in the evening. Between 14:00 and 20:00 no significant correlation was found. For EV, it was vice versa, with a negative correlation in the morning and a positive one in the evening (from 18:00h to 2:00h). DI correlated negatively with the alertness rating. The highest relations were found between 16:00 and 18:00 (see Table 3). CSM followed the same correlation pattern as MA.

Table 3. Pearson Correlations Coefficients between Morning Affect (MA), Eveningness (EV) and Distinctness (DI), Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM) and Subjective Level of Alertness across the day

Note: n = 261; *p < .05, **p < .01; ***p < .001.

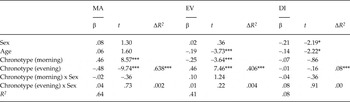

Finally, we explored differences in MA, EV and DI considering chronotype classifications obtained from CSM scores. Also, the possible effect of sex was considered. Morning (n = 77), intermediate (n = 111), and evening (n = 73) chronotypes were defined using relaxed criteria of percentile 30 (cut-offs 32 and 44 of CSM in this present sample). Multiple regressions predicting MA, EV and DI subscales by sex, age, and chronotype were run. Sex and chronotype variables were included as dummy variables (see Table 4). MA was positively predicted by morning chronotype (R 2 = .64), EV was negatively predicted by age (young people reported higher EV) and positively by evening chronotype (R 2 = .41), and finally DI was negatively predicted by sex (women reported higher DI than men) and age (young people reported higher DI; R 2 = .08). Interactions of chronotype with sex were non-significant.

Table 4. Regression model (standardized betas, significance levels and adjusted R square) with Morning Affect (MA), Eveningness (EV) and Distinctness (DI) as criteria variables and Sex, Age and Chronotype as predictors

Note: n = 261; *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Sex: women = 0; men = 1; Chronotype (morning): morning = 1; intermediate = 0; evening = 0; Chronotype (evening): morning = 0; intermediate = 0; evening = 1.

Discussion

Without any modifications, the CFA already showed a mediocre fit and after the modification (correlated error covariances of items 14 and 15), the fit of the MESSi’s structural model was acceptable. Then, the Spanish scale showed a comparable structure as in the original German scale. This is important, because Germany and Spain differ much in the morningness-eveningness preference (Díaz-Morales & Randler, Reference Díaz-Morales and Randler2008), thus these two countries are ideal within Europe for a transcultural comparison. Similarly, alpha coefficients were good to satisfactory, and as in the German sample, the alpha level of the Distinctness scale was lowest.

Convergent validity was obtained with correlations of MA and rise times, as well as between EV and bed times. As predicted, Conscientiousness as personality trait showed the strongest positive correlation with MA. Interestingly, Emotional Stability showed the strongest negative correlation with DI. This is a new and interesting result because morningness has been related to stability as meta-trait at emotional (neuroticism), social (agreeableness) and motivational (conscientiousness) domains to morningness, whereas eveningness has been related to plasticity as meta-trait at behavioral (extraversion) and cognitive (openness) modalities (DeYoung, Hasher, Djikic, Criger, & Peterson, Reference DeYoung, Hasher, Djikic, Criger and Peterson2007). The results of the present research confirm that more conscientious people show their peak of circadian arousal earlier in the day probably by biological (e.g., serotonergic function) and social mechanism (e.g., conform with social norms), but add new findings about the negative relation between Emotional Stability and Distinctness. The amplitude characteristics seem to be considered as an important component of the circadian rhythms in the health and occupational domains, in particular at work where it could predict the tolerance of an individual to shiftwork or jetlag (Saksvik, Bjorvatn, Hetland, Sandal, & Pallesen, Reference Saksvik, Bjorvatn, Hetland, Sandal and Pallesen2011). The subjective amplitude reflects the ability of a person to modulate one’s own psychophysiological state according to the time of day, and represents the subjective feeling of distinctness of daily changes and is thought to reflect the strength of the human circadian system (Oginska, Reference Oginska2011). Next studies could explore this relation using a better measure of personality, given that neuroticism (low Emotional Stability) has been characterized by higher emotional lability (volatility), irritability and anger, excessive monitoring of mood, high NA variability and reactivity in daily interactions (Ormel et al., Reference Ormel, Bastiaansen, Riese, Bos, Servaas, Ellenbogen and Aleman2013).

Subjective alertness rating during the day was positively related to MA in the morning, and negatively in the evening. In EV, the situation was in the other direction. This confirms previous findings on alertness and morningness-eveningness at different times of the day (Bohle et al., Reference Bohle, Tilley and Brown2001). Finally, MA and EV were related with chronotype, but not with DI. This is important because it shows that DI is a distinct factor/dimension from MA and EV, and thus not related to morning or evening preferences. As expected, morning persons had a higher MA and a lower EV than evening persons, corroborating previous findings. Also, age was positively related with MA, which was expected according to developmental studies about morningness-eveningness across the lifespan: morningness decreases during adolescence and increases during adulthood (Roenneberg et al., Reference Roenneberg, Kuehnle, Juda, Kantermann, Allebrandt, Gordijn and Merrow2007). Sex differences on MESSi indicated that women reported higher DI than men. Sex differences could be expected because Zeitgebers entrain arousal rhythms to the sleep-wake cycle (Díaz-Morales & Sánchez-López, Reference Díaz-Morales and Randler2008; Merikanto et al., Reference Merikanto, Kronholm, Peltonen, Laatikainen, Lahti and Partonen2012; Randler, Reference Randler2007). Given that social cues are capable of behaving like Zeitgebers and that sexes differ in socialization and response to social signals, Matthews suggested that anxious women would be more motivated than anxious men to attend to time cues and maintain a normal sleep-wake cycle (Matthews, Reference Matthews1988, p. 283). This is also related to recent findings, which reveals a distinct pattern of sensitivity to the phase-shifting effects of light according to gender (Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Menna-Barreto, Miguel, Louzada, Araújo, Alam and Pedrazzoli2014).

These preliminary data should be supported by a higher sample size to further investigate the scale construct. Although the sample size was adequate to factorial analysis, a higher sample size could facilitate a typological analysis of chronotypes using phase (MA and EV) and amplitude (DI) components of morningness-eveningness. However, chronotyping based on this has yet to be established and cut-off scores have to be developed. Another limitation of the present study was the use of the TIPI, which was used to confirm well established relationships (i.e., positive relation between morningness and conscientiousness). This should be repeated using longer Big-Five instruments. However, the negative relation between Distinctness and Emotional Stability opens a new research question about the construct validity of subjective amplitude dimension of circadian rhythm. Future research should determine these personality correlates of Morning Affect and Distinctness in other populations. Such an extension of our investigation is particularly important because of the regular shifts in circadian rhythm that occur over the lifespan. Finally, the use of online self-report method has the advantages of low cost, real-time access and flexibility in the response coming at the disadvantages of limited sampling and the lack of a trained interviewer to assist participants. Online procedure used in the present study was directed to test the psychometric properties of a new measure of morningness-eveningness (i.e., MESSi) and future studies must replicate these results with other collection procedure.

Appendix:

Spanish version of the MESSi (Morningness-Eveningness-Stability Scale improved)

Indica el grado de acuerdo (5) o desacuerdo (1) con cada una de estas frases.