A French sympathizer of the American Revolution imagined this charming scene. “They say that in Virginia the members chosen to establish the new government assembled in a peaceful wood, removed from the sight of the people, in an enclosure prepared by nature with banks of grass, and that in this sylvan spot they deliberated on who should preside over them.”Footnote 1 Michel René Hilliard d’Auberteuil had no local knowledge of Virginia, so there is perhaps too much Rousseau and not enough Richmond in his portrait. But still he captured some essential truths about the ideals of enlightenment in the American Revolution: the appeal to nature as a primal origin for human society; the deliberate choice of government by representatives of the people; and, above all, the optimism that drove the formation of new governments on principles of kingless republicanism. The core ideal of the new, transatlantic idea of enlightenment was that human reason could understand, change, and improve the world. Its relationship to the phenomenon we call the “American Revolution,” however, has always been controversial.

How do we even begin to approach so grand a topic as enlightenment and the American Revolution? It helps to listen to what eighteenth-century Americans themselves said about it. To do that, we have to set aside – or at least be aware of – some of what has been said about the topic over the last seventy years.

Since the Cold War era, scholars of the United States have wrapped the topic in a warm cloak of approval that sometimes tells us more about their own concerns than those of the eighteenth century. Surveying the destructions of the Second World War and anxiously eyeing the Soviet Union, American historians looked to the founding era as a bulwark against totalitarianism. They offered a new label – “The American Enlightenment” (a term unknown in the eighteenth century) – as an ideological bomb shelter against Nazism, communism, and fascism. And because their modern concerns were political, they collapsed the broad intellectual movement of enlightenment into the narrowly political project of the American Revolution.Footnote 2 As Henry Steele Commager put it in 1977, enlightenment ideas were “imagined” in Europe and then “fulfilled” in the American Revolution.Footnote 3 For over half a century, this Cold War story has given a satisfying, triumphal cast not just to “The American Enlightenment,” but to the American Revolution itself. It proves irresistible even today.Footnote 4

By contrast, people living in eighteenth-century America used only the lower-case terms “enlightened” and “enlightenment.” To them, enlightenment was process, not product. It was not the culmination of European ideas in a political event across the sea, but rather an ongoing, never-completed effort to establish happy human societies based on reason. These ideas came not just from eighteenth-century Europe, but through a long-term transatlantic exchange of ideas. For people in the eighteenth century, enlightenment also involved a vast range of topics beyond politics: science, religion, art, literature, history, ethnology, political economy, and more.Footnote 5 Enlightened ideas appealed to and were articulated by both the educated elite and those with less access to power and privilege.Footnote 6 The uniting thread for all these people and arenas of thought was the hope that reason could light the path forward to a better tomorrow.

As a process rather than as a product, the eighteenth-century idea of enlightenment involved uncertainty and anxiety. The barriers could seem insurmountable in a world of pain, ignorance, error, oppression, and despotism. Anachronistic modern labels (such as “Radical Enlightenment” or “Moderate Enlightenment,” which were never used in the eighteenth century) judge efforts at enlightenment according to whether they meet our modern criteria of long-term success or failure. These labels fail to capture the real ambivalence that characterized efforts at enlightenment around the Atlantic. Like others in Europe and Spanish America, revolutionary Americans mixed hope with doubt about whether enlightenment could ever be achieved. It loomed like a distant summit, in sight but difficult to reach. “My friend,” wrote the French economist Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours to his friend Thomas Jefferson after the American Revolution, “we are snails and we have a mountain range to climb. By God, we must climb it!”Footnote 7

Some of this uncertainty involved whether airy ideas could cause a revolution in government. Rather than taking sides in a debate that continues to this day, we can start with the opinions that eighteenth-century observers themselves hazarded: that the revolution was revolutionary precisely because it showed the reality of enlightenment. The term “American Revolution” was coined as early as 1777 to describe the political break with Britain. But it took the first histories of the “American Revolution,” written in the 1780s, to claim that the American Revolution showed evidence of the progress of humanity toward a better world of reason, rights, and government by the people. That this interpretation seems familiar to us is exactly the point: the first histories of the American Revolution were themselves the product of an enlightened view of the world. Thus, in some way, the whole concept of an “American Revolution” resulted from the ideal of enlightenment. John Adams insisted upon the efficacy of ideas in causing what he called the “real” American Revolution. “But what do We mean by the American Revolution? Do We mean the American War? The Revolution was effected before the War commenced. The Revolution was in the Minds and Hearts of the People … This radical Change in the Principles, Opinions Sentiments, and Affection of the people, was the real American Revolution.”Footnote 8

It is not enough, then, to describe the role of enlightened ideas in the American Revolution, as though taking attendance with a clipboard. For the “American Revolution” itself was a narrative frame imposed in the 1780s and later on a string of otherwise inchoate events by people who yearned to see the forces of enlightenment at work. The long-term results of their efforts remain visible today. R. R. Palmer’s The Age of Democratic Revolution crafted an ambitious, celebratory Atlantic genealogy for the American Revolution that has inspired decades of scholarship (including the Cambridge History of the Age of Atlantic Revolutions). Palmer’s genealogy cast the American Revolution – and the subsequent “Age of Atlantic Revolutions” (another post-Second World War coinage) – as the cradle of twentieth-century democracy and even, as Palmer styled it, “Western Civilization.”Footnote 9

As these Cold War genealogies become artifacts of history rather than present ideology, the topic of “enlightenment and the American Revolution” demands two approaches. The first is to document how eighteenth-century people themselves understood the ideal of enlightenment in the project of political independence and republican nation-formation. The second is to show how these ideas laid the groundwork for our present understanding of the American Revolution. This chapter is organized around four major concepts – nature, progress, reason, and revolution – which offer a sketch map to a body of thought so vast and diverse that it defies complete representation. Still, they can point to a few of the main lines of thought that animated Americans and their contemporaries around the Atlantic in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

The North American Context of Enlightenment

Eighteenth-century North Americans shared many ideas about what it meant to be enlightened with other people around the Atlantic. They held in common the new idea that human reason could understand the world using empirical data from the five senses (rather than revelation or superstition), and that this understanding could then be used to improve the world. According to people who considered themselves enlightened, the future should be better than the present and the present better than the past. Properly harnessed, all human efforts could point to a golden future of human happiness.

Many historians used to argue that enlightened ideas were born in Europe (chiefly in France) and then migrated to America. We can call this the “diffusion” hypothesis. Today, owing in part to the digitization and widespread availability of archival documents from the colonial periphery, opinion has shifted to the view that enlightenment ideas emerged from many points and circulated widely. “Network” rather than diffusion is now the organizing paradigm to describe this process (though the textile metaphor was not used in the eighteenth century to describe it). At any rate, the vehicles for circulation included every manner of published media as well as a lively trade in objects, ranging from moose pelts to microscopes. All these lit up conversations across thousands of miles of water and land. National and regional strands of enlightenment emphasized certain ideas and attitudes.Footnote 10

Late eighteenth-century North America was one regional variation within this Atlantic world of ideas. By comparison with Europe – with its princely patronage of universities, academies, museums, and libraries – colonial America was thin on institutions of enlightenment. Still, by the late eighteenth century Americans enjoyed high literacy levels, buoyed by a steady stream of books imported from Europe (and especially London), as well as locally published magazines and newspapers that reprinted the latest opinions and conjectures. By the 1760s, there was enough intellectual infrastructure in colonial North America – colleges, printing presses, libraries, a few museums and academies – to support the intensive written communication networks on which the American Revolution ultimately hinged.Footnote 11

For this would be a revolution by document. As the first of what are today called the “Atlantic revolutions,” the American Revolution launched what would eventually become so normalized that it can easily slip from view: the publication and widespread international circulation of documents not just to provoke revolutionary activity, but to embody the meaning of revolution itself. Although the late eighteenth century was still an oral culture (as the “Declaration” of Independence reminds us), the legalistic formulation of universal principles on which the American and later revolutions hinged could be achieved only in the more permanent medium of writing.Footnote 12

And so writing there was. By the 1760s, colonial American “committees of correspondence” were linking distant colonists in a common project of information-gathering and eventually shadow governance. The first state constitutions, the Declaration of Independence, and the federal Constitution emerged from the hope that documents – especially published documents – would form bulwarks against despotism. The Declaration of Independence and the state constitutions were immediately translated and published in France, facilitating further circulation. (Though in their exuberantly varied translations of keywords such as “mankind,” the French also gave the lie to enlightened dreams of finding a universal natural language.)Footnote 13

By raising sight above the other senses, Americans celebrated their revolutionary documents as exempla of clarity. One proponent of the new federal Constitution claimed that it was a “luminous body” whose “light … was so clear that nothing more was wanted.”Footnote 14 They also pioneered new visual forms that might uncover the truths that the rigidly sequential syntax of prose concealed or distorted. Tables, questionnaires, timelines, pie charts, and diagrams promised clear windows into truths that could topple illegitimate authority. Americans also reached for optical metaphors to understand their new representative governments: were they mirrors or miniatures of the people?Footnote 15

But doubts lurked amid the optimism. James Madison wondered whether mere “parchment barriers” could restrain the accumulations of power that led to tyranny.Footnote 16 Language itself resisted the clarity to which enlightened Americans aspired. Even as he defended the words of the Constitution that he had just helped to draft, Madison pondered the limits of human language and therefore all human knowledge in The Federalist. God spoke clearly, but the “cloudy medium” of human language muddied meaning. As human and therefore necessarily imperfect creations, the Constitutional convention and the Constitution itself could only wallow in “obscurity.”Footnote 17

Forms that promised clarity merely cast new shadows. The major documents of the American Revolution are all either literally enumerated lists (in that they have actual numerals, whether Roman or Arabic: these include the state and federal bills of rights; the Articles of Confederation; and the federal Constitution) or unenumerated lists (the grievances against King George III in the Declaration of Independence). Like diagrams and tables, enumerated lists – especially lists of rights – sought political safety in visibility.

But by announcing presence, enumeration also exposed absence. The Ninth Amendment confronted the problem without resolving it: “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” Critics quickly seized on the problems of this amendment. James Iredell of North Carolina called the Bill of Rights a “snare” rather than a “protection.” He imagined a distant future in which the omitted rights – the potential infinity of rights left out of the enumerated rights – came back to haunt them. “No man, let his ingenuity be what it will, could enumerate all the individual rights not relinquished by this Constitution. Suppose, therefore, an enumeration of a great many, but an omission of some, and that, long after all traces of our present disputes were at an end, any of the omitted rights should be invaded, and the invasion be complained of; what would be the plausible answer of the government to such a complaint?”Footnote 18 It was typical of the anxious open-endedness of this era’s frame of mind that the problem would be phrased as a question.

Nature

The word “nature” is everywhere in the political texts of the American Revolution. Americans invoked natural law, natural man, natural rights, human nature, and the state of nature. In the 1760s and after, the appeal to nature became a way to delegitimize claims to authority that rested on other foundations: history, custom, divine access, and lineage. Nature was now seen to come before all of these. Before King George III, before Parliament, before Magna Carta, before Christianity, before the first biblical kings, before the Egyptians, before Adam himself: there lay nature.

The words “Nature and Nature’s God” in the Declaration of Independence remind us that nature and God were not sharply differentiated. Nature could simultaneously be both the creator and the product of God’s creation. Both God and nature were transcendent, creative forces operating from time immemorial. Now, after the Scientific Revolution, religion itself began to be infused with ideas taken from the scientific study of the natural world. “Natural laws” like those documented by Isaac Newton attested to God’s desire that humanity should use reason in all realms of life, including some matters of faith. Miracles seemed increasingly implausible.

Humans stood upon an isthmus between mundane and divine nature. They were both a product of God’s creation but also possessed of a shared “human nature” (another new term) that, like the trees and planets, was subject to empirical investigation. People could inspect their own psychology, as David Hume did in his A Treatise of Human Nature (1739). Still, some parts of humanity remained opaque. One was “conscience” as a faculty of the mind, an inner sanctum of morality or even divinity. It was now walled off from state power and state observation. Thomas Jefferson eventually reached for a metaphor of both physical and optical blockage – a wall – to affirm his support for the separation of church and state.

Early in the 1760s, Americans seized on one of these new nature ideas to frame their growing discontent with British taxation: the “state of nature.” This hypothetical origin of all human societies emerged from the political struggles of seventeenth-century Britain that pitted absolutist kings against Parliament. Theorists such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and others sought a cradle for rights that was independent of monarchical largesse. By “rights” they meant entitlements to property, life, liberty, and other desirables that had a long English history stretching even beyond Magna Carta in the thirteenth century. But now, with the fiction of a “state of nature,” rights could transcend English history and find a universal appeal as the common birthright of humankind. John Locke’s description of the state of nature in his Two Treatises of Government (1689) resonated with American colonists eager to justify the universality of their rights claims. “Man being born, as has been proved, with a Title to perfect Freedom, and an uncontrouled Enjoyement of all the Rights and Privileges of the Law of Nature, equally with any other Man, or Number of Men in the World, hath by Nature a Power … to preserve his Property, that is, his Life, Liberty and Estate, against the Injuries and Attempts of other Men.”Footnote 19

Although the state of nature was widely understood to be a useful fiction (Rousseau thought it “no longer exists, perhaps never existed, and will probably never exist”), Locke drew many of his examples from the native peoples of North America.Footnote 20 As Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and to the Lords Proprietor of Carolina, Locke had read extensively about the American Indians. “Thus in the beginning, all the world was America,” he announced in a Genesis-like formulation in his Two Treatises. (That Locke’s understanding of Indian polities was empirically incorrect was for later commentators to establish and publicize.) Locke’s equation of America with natural political origins became part of the background noise of the revolutionary era. It helped to encourage a local strand of nationalism in which the United States became nature’s nation. This would be realized most fully in the nineteenth century, but its seeds were sown much earlier.

The “state of nature” opened the door to another new idea: “society.” Today we take for granted that human beings live in societies. But the idea of society as the primordial, prepolitical container for human activity emerged only in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The term “society” had previously existed to refer to smaller, voluntary associations, such as London’s Royal Society, the major British scientific institution of its day. But it now acquired powerful political uses. Referring to a community with shared customs, laws, or institutions, the new use of society first of all presumed that human beings were fundamentally social: to live in society was “human nature.” Society was thought to be shaped by natural laws of human behavior and organization that could be observed and categorized. Properly understood, society would be the great engine of human progress. “What a man alone would not have been able to effect,” explained the Abbé Raynal in one of the first histories of the American Revolution, “men have executed in concert … Such is the origin, such the advantage and the end of all society.”Footnote 21 The thickening concept of society led to the proliferation of other new terms, such as the “social contract,” “civil society,” “social happiness,” “science of society,” and eventually “sociology.”Footnote 22

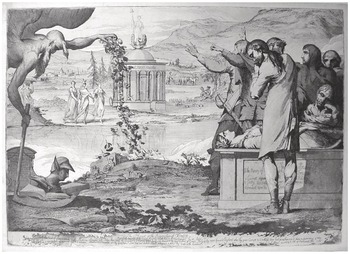

Figure 1.1 The Phoenix, or the Resurrection of Freedom (1776). Allegory depicting the death of liberty in Europe and its new home in America; a temple, lettered “Libert. Americ.,” stands on a distant shore beyond which stretches a fertile landscape; in the foreground, on the left, Father Time casts flowers on the remnants of Athens, Rome, and Florence, while on the right, a figure representing British liberty lies on a tomb mourned by seventeenth-century republicans Algernon Sidney, John Milton, Andrew Marvell, John Locke, and James Barry, the artist who made this print, himself; a man with shackled ankles stands in front of the tomb with a tattered copy of Habeas Corpus protruding from his coat.

Following the logic of the state of nature was the new idea that government was a contract between ruler and ruled. All humans lived in society. Only by choice, and through consent among equals, could governments be formed from society. Government therefore became not a God-given reality, but a human-created contract among consenting equals. Government by consent implied that the contract could be broken if certain conditions were met (which the Declaration of Independence achieved by positing “a long train of abuses and usurpations”). This political rupture could result in the most drastic break of all: revolution.

The major state-of-nature theorist for American revolutionary politics was “the celebrated Montesquieu” (as Americans almost invariably called him). A French nobleman who had once lived in London and deeply admired the balanced British constitution, Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de la Brède et de Montesquieu was the author of the widely known and translated book, De l’esprit de loix (The Spirit of Laws). Published in 1748, it was soon translated into English and had enormous influence all over Europe and the Americas. Its popularity was in some sense remarkable. The book was poorly organized, aphoristic, and often opaque. “What does he mean by a Man in a State of Nature?” wondered John Adams when he read Montesquieu in 1759.Footnote 23 Still, Montesquieu’s name was held in such high regard that even the arrival of his grandson in revolutionary Philadelphia as part of the French military corps was duly noted.Footnote 24

Montesquieu gave revolutionary Americans a framework for understanding the natural origin and major types of society and government over time and place. In his view, governments were not entities given by God, but instead institutions created by human beings according to the “humour and disposition” of the particular people who created them.Footnote 25 Accessible to reason, government could be comprehended, categorized, and also reformed.

Observing the diversity of regimes around the world over time, Montesquieu divided them into three kinds, each with its own principle or “spirit”: republican (resting on virtue); monarchical (resting on honor); and despotic (resting on fear). One of the greatest dangers to government was the desire for power, which Montesquieu believed formed part of human nature. The only remedy was to check that power – or as Montesquieu put it: “it is necessary, from the very nature of things, power should be a check to power.”Footnote 26 In Book 6, Montesquieu laid out the scheme for which Americans in the Constitution-making era admired him: separation of the three powers of government (legislative, executive, and judicial) to block the tyrannical growth of power in any one of them. “There would be an end of every thing, were the same man, or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals.”Footnote 27

State-of-nature arguments made a dramatic early appearance in British America in the wake of the Sugar Act (1764) and the Stamp Act (1765). Massachusetts lawyer James Otis’ The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (1764) was the first colonial pamphlet to respond to British policies by asserting rights derived not from human institutions, but instead from a state of nature governed by natural law and God. Citing Locke, Otis posited a “state of nature” governed by a “law of nature.” Only by giving their “consent,” could people leave the state of nature to form “civil government.” The only good governments were those founded on “human nature, and ultimately on the will of God, the author of nature.”Footnote 28 This scene-setting permitted Otis to proceed to his primary claim: that all British subjects born in America were “by the law of God and nature, by the common law, and by act of parliament … entitled to all the natural, essential, inherent and inseparable rights of our fellow subjects in Great-Britain.”Footnote 29

The idea gained traction quickly, in part because it supplied a more universal language for rights claims than those offered by British history alone. John Adams was soon thundering about nature as a primordial source of rights in his 1765 opposition to the Stamp Act. “I say RIGHTS, antecedent to all earthly government – Rights, that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws – Rights, derived from the great Legislator of the universe.”Footnote 30 The state of nature had become commonplace in colonial rhetoric by the time Thomas Jefferson invoked it in his Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774). In many ways, this was a traditional document: it took the ancient and venerable form of a petition to the king, and it was grounded in historical precedents stretching back to the Anglo-Saxons. But sprinkled throughout was the new language of the state of nature as the ultimate origin of colonial – and universal – rights. Americans “possessed a right which nature has given to all men,” he began, of “establishing new societies under such laws and regulations as to them shall seem most likely to promote public happiness.”Footnote 31

The new state constitutions drafted after the mid-1770s contained bills of rights that reflected both their specific origin in British common law and the fashionable new appeal to nature. Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason in June 1776, opened with soaring rhetoric about rights emerging from a primordial state of nature. “That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” One historian has called this “a jarring but exciting combination of universal principles with a motley collection of common law procedures.”Footnote 32 It was indeed exciting enough that Thomas Jefferson drew on Mason’s universalizing rights language in the Declaration of Independence. And it became the constant refrain through the war years that by throwing off British rule, Americans had entered into a state of nature – understood in the new, abstract philosophical sense of the term. “And yet at this time the people were in a great degree in a state of nature, being free from all restraints of government,” wrote the secretary of Congress to John Jay in 1781.Footnote 33

The idea of natural law and a state of nature gave Americans a new political language with which to frame their opposition to British taxation and ultimately to justify resistance and revolution. The language played a large role in the first state constitutions and bills of rights. As time passed, the explicit political appeal to the language of nature receded, ultimately playing a minor role in the federal Constitution-making era. By that time, the idea of nature had become so thoroughly normalized as a way of thinking about political origins and justifications that it was usually assumed without further need of articulation and embellishment.

Progress

A second major assumption of enlightened people was progress. A new and powerful interpretation of history, the idea of progress asserted that with reasoned human effort everything should get better. Progress was a bracing new vision of human potential that contrasted and ultimately displaced the two other major historical interpretations dominant for over two millennia. The biblical narrative had emphasized a Fall from Eden due to human sin in a cosmic drama whose meaning lay largely outside the span of a human life. Classical history involved ever-repeating cycles of political rise and fall that hinged on civic virtue and civic vice. Progress instead implied an ever-improving state of affairs largely by and for the people.

The highest goal of progress was happiness. Today we talk about happiness in personal terms, as self-fulfillment. The eighteenth century further emphasized another, more expansive meaning of happiness: what they called “public happiness” and “social happiness.” Nations and peoples enjoyed public or social happiness when they were shielded by wise leaders against internal threats and external enemies. “Politicks is the science of social happiness, and the blessings of society depend entirely on the constitutions of government,” John Adams explained in 1776.Footnote 34 This political meaning of happiness made it a frequent partner of the word “safety.” The French vice admiral d’Estaing invoked this meaning to George Washington after the disastrous siege of Newport, Rhode Island. “The happiness and safety of America is your own work.”Footnote 35 (Today the term “national security” retains some of this eighteenth-century flavor.) The opposite of public or social happiness was not sorrow but anarchy or despotism. And the Declaration’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” may have referred less to personal fulfillment than to the right to a collective political state of security.

The young republic faced formidable barriers to progress. Revolutionaries wondered where the new United States – as a sovereign nation – stood in the scale of civilization. This seems like an obscure worry to us today, but in the eighteenth century it had everything to do with political survival. The idea that all societies progressed through a series of stages from savagery to civilization had gained widespread popularity in the eighteenth century and was eagerly taken up by Americans. It was the special concern of a group of Scottish thinkers, including Adam Ferguson, John Millar, Lord Kames, and William Robertson. Using “data” (a new term from this era) collected from European empires around the world, as well as much somber reflection from the safety of their own Scottish armchairs (which is what made this kind of history “conjectural”), they proposed that all societies, in all times and places, developed upwards along a staircase of increasingly complex and sophisticated organization. They used material circumstances – what Marxists (whom the Scots deeply influenced) would later call “the mode of production” – as their guides to their categories. Thus, all societies moved from nomadic, animal-chasing “savagery” to settled agriculture (“barbarity”), and finally reached so-called “civilization” embodied in its highest form in commercialized eighteenth-century Europe. European imperialism could be justified as a civilizing process for savage and barbaric peoples. But as a former colony in a region still heavily populated by nomadic “savages,” the United States faced skepticism about its capacity for ascent on the scale of civilization.Footnote 36

Part of the solution hinged on climate. In the eighteenth century, climate was thought by influential theorists to be the major agent shaping human societies and governments. Climate could account for human diversity within the biblically sanctioned story of monogenesis, or descent from a single pair in Eden. Much to the concern of American revolutionaries, however, some European naturalists, such as the Comte de Buffon and Cornelius de Pauw, had asserted that the allegedly cold, humid climate of the Americas shriveled all life forms – plants, animals, and humans. It even diminished Europeans who dared to settle there.Footnote 37 Revolutionary Americans anxiously eyed the other civilizations of the Americas to determine where they stood vis-à-vis the nomadic Indians of North America (“savages”) and the urbanized Aztecs of central America (“semi-civilized”).Footnote 38 Thus, a major question for American revolutionaries was whether their new nation, led by inexperienced statesmen born or now living in an unfavorable climate, could ever ascend to full civilization in the eyes of Europeans.

Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, written in the early 1780s and published in France, Britain, and the United States later in that decade, exemplified the anxious uncertainty plaguing white Americans about where the new nation would stand in the scale of civilization. The “state” in Jefferson’s title is a pun: it refers both to the political entity of Virginia (formerly a colony, now a state), as well as to its fluctuating climatic condition. The two meanings were related: would a republican state create a favorable climate? and was the climate of Virginia favorable for successful republican government?

Like so many other texts of this era, the Notes on the State of Virginia takes the form of an enumerated list. The list consists of Jefferson’s responses to the queries of François Barbé-Marbois, the secretary of the French legation in Philadelphia. Barbé-Marbois wondered about the condition of the new American states recently seceded from Britain. Jefferson filled his text chock-a-block with tables assuring his French audience that American plants and animals were as large as or larger than those in Europe.Footnote 39 And so were the people: Jefferson was at pains to argue that the American Indians, though native to the American climate, could ascend the scale of civilization since their current inferiority was the result “not of a difference of nature, but of circumstance.”Footnote 40 The new republic would create a favorable climate for civilization, which would then civilize the Indians. Jefferson’s “Empire of Liberty” hinged on this climatic theory, which he pursued as president through the Louisiana Purchase and other policies.Footnote 41

The question of United States’ civilization was also debated at the international level – or, in the terminology of the era, as part of the “law of nations.” Like so many areas of political thought in the revolutionary era, this one drew from the idea of natural law. Beginning in the seventeenth century, as European empires expanded across land and sea, a cadre of European jurists tried to determine how law governed the actions of whole nations in relationship to one another. Eighteenth-century Americans were familiar with theorists such as Samuel von Pufendorf, Hugo Grotius, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui. They were especially drawn to Emer de Vattel, whose Le droit des gens (The Law of Nations, 1758) derived an idea of relations between sovereign states from a prior conception of natural law and human governments formed out of a state of nature.Footnote 42 Vattel believed that the law of nations was a science accessible to human reason. “There certainly exists a natural law of nations, since the obligations of the law of nature are no less binding on states, on men united in political society, than on individuals.”Footnote 43

Vattel’s ideas were relevant because American diplomatic failures after 1776 had dramatically revealed to them that recognition of a new nation in the system of the “law of nations” was earned and not a given. The federal Constitution emerged not just from domestic concerns, but in an international context where a “law of nations” based in natural law was thought to govern the interactions of “civilized” nations.Footnote 44 In the legal case of Rutgers v. Waddington (1784), mayor James Duane of New York explained his reverence for the law of nations as an obligation for newly independent Americans to learn and cultivate:

Profess to revere the rights of human nature; at every hazard and expence we have vindicated, and successfully established them in our land! and we cannot but reverence a law which is their chief guardian – a law which inculcates as a first principle – that the amiable precepts of the law of nature, are as obligatory on nations in the mutual intercourse, as they are on individuals in their conduct towards each other … What more eminently distinguished the refined and polished nations of Europe, from the piratical states of Barbary, than a respect or a contempt for this law.Footnote 45

Lurking in the background of the new “progress talk” was the fear that economic progress would cause a decline in the civic virtue on which the new republic rested. Traditional thinking about republics, inherited from the Greeks and Romans, identified farming as the source of such virtues as self-sacrifice that upheld republics. But as the United States “progressed” up the ladder of civilization – with more manufactures, commerce, cities, and other markers of “civilization” – what would become of those sturdy agricultural virtues? The fears worsened with the westward expansion across the Appalachians in the decades after independence. To some, national expansion was an undeniable sign that the empire-rejecting republic had now become an empire in its own right.Footnote 46

Thus, the idea of progress was from the first a double-edged sword. It filled Americans with hopes for a happy future of progress toward civilization. It provided a frame for filling with higher meaning their political break from Britain. But its linearity – its insistence that all movement through time must necessarily be either progress or degeneration – became an interpretive trap that remains with us today.

Reason

Revolutionary Americans thought a lot about how their own minds worked. They could not improve the world unless they understood their own perceptions of what was true and good. But the Declaration’s “self-evident” truths masked a real question about how fallible humans could discern truth. The dark conspiracies allegedly brewing in Whitehall heightened colonists’ desire to find a path to truths that were not in fact self-evident at all.

The political texts of the American revolutionary era reflect their concerns about the mind’s capacities to grasp external realities. Like others at this time, American revolutionaries held up “reason” as a universal human attribute that could discern empirically valid conclusions based on information delivered to the mind through the five senses. John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) and the works of Scottish philosophers such as Frances Hutcheson and Thomas Reid were mainstays of British American reading. These books explained how the mind formed ideas about reality from sensory perception mixed with reflection. As a property common to all humanity, this way of reasoning was termed “common sense.”

The mind’s powers included not just cold calculation but also a “moral sense” based in part on sensory perceptions such as pleasure and pain. This moral sense – variously called the affections, sensibility, or sympathy – formed the basis for human social action, connecting self and society.Footnote 47 Sensibility was “the great cement of human society,” as one Scottish philosopher put it.Footnote 48

In 1776, pain and pleasure joined reason in a new political calculus. The Declaration of Independence raised not just happiness but pain to a high pitch of political significance. The colonists endured three versions of suffering (suffer, sufferable, and sufferance), along with tribulations that were both “uncomfortable” and “fatiguing.” Earlier that year, Thomas Paine in his bestselling pamphlet Common Sense (1776) had both popularized and politicized Scottish epistemology. Paine’s achievement was to pair “common sense” with republican government. The pamphlet’s title announced that a shared commitment by ordinary people to overthrowing British rule was the only reasonable conclusion available from an appraisal of sensory data regarding trampled rights and liberties. No special knowledge or erudition was required: Paine’s text deliberately lacked footnotes. He would offer nothing more than “simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.”Footnote 49

But common sense raised as many political questions as it answered. Alexander Hamilton singled out the “important question” in the first essay of The Federalist: “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”Footnote 50 Did “the people” as a whole possess enough reason and common sense to govern? And which individual people possessed those traits? These emerged as two of the most fiercely debated questions of the revolutionary era.

The struggle led to one of the great unexpected and ironic outcomes of enlightened thought: the new, hierarchical categorization of humanity based largely on reasoning capacity. Women, children, slaves, and Native Americans among others now entered a period of major reassessment as a result of the new ideal of a reason-based republic.Footnote 51 We can consider African Americans and women more closely here.

For African Americans, the American Revolution represented two linked achievements: the largest flight by slaves since the first Black slaves had arrived in English North America in the early 1600s, and the occasion for the first rights-based articulations of African American liberty. There were approximately half a million African and African American slaves in the United States in 1776; the small free Black population clustered largely in urban areas. In the years leading up to independence, free Blacks in the north moved quickly to apply the idea of natural rights to their personal enslavement, mirroring the language free white colonists used to describe political enslavement to Britain. With access to print through white sympathizers such as John Woolman and Benjamin Rush, they could more broadly spread the critique of Black enslavement on the grounds of natural rights. Some slaves in Boston also petitioned the legislature for emancipation using the language of rights.

In the decades after 1776, the language of nature and rights pervaded the new movement of antislavery activism. The movement gained support from the fact that ultimately approximately 9,000 African Americans served in the war against Britain. In Fairfield and Stratford, Connecticut, a band of slaves petitioned the wartime legislature in May 1779, asserting a common human nature.

[R]eason and revelation join to declare that we are the creatures of that God, who made of one blood, and kindred, all the nations of the earth … We can never be convinced that we were made to be slaves … Is it consistent with the present claims of the United States to hold so many thousands of the race of Adam, our common father, in perpetual slavery? Can human nature endure the shocking idea? … ask for nothing but what we are fully persuaded is ours to claim.Footnote 52

Many northern states passed emancipation acts in the wake of independence that allowed for the gradual liberation of slaves.

Yet enlightened ideas about republican participation based on reason also worked against African American claims to equality. For centuries, the Genesis story of Creation, in which all humanity had descended from an original pair, had served to maintain the idea that all humans ultimately formed part of the same human family. Differences in appearance and behavior could be attributed to climate or custom. American slaveholders in the post-independence era, however, fearful that rights-based claims to equality would lead to widespread slave emancipation, began to argue that African Americans were by nature intellectually inferior to Whites. They emphasized that this intellectual inferiority did not result from climatic effects so much as from unchangeable heredity. Lacking the full complement of reason necessary for participation in republican governance, African Americans should therefore either remain in servitude or, if freed, be colonized elsewhere.

Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia contained the American revolutionary era’s most detailed catalog of Black inferiority. A Virginia slaveholder who over the course of his life held approximately 600 slaves, Jefferson cited “the real distinctions which nature has made” – that is, permanent Black intellectual, physical, and moral inferiority to Whites. Jefferson’s essay was among the first to propose that Black inferiority was due to innate difference, lodged in inheritable bodily characteristics that would not change with climate.Footnote 53 Thus, the revolutionary era produced both the first claims to common humanity based on “natural” rights, but also the first arguments that “nature” itself created immutable inferiorities.

White women in the United States also lodged new claims for reasoned participation in the republic. Women had long been thought of as deficient in full mental capacities, though this had generally formed part of a larger biblical argument about the sin of Eve. Now, republicanism’s claims to the equality of all human beings put the question of women’s natural reasoning capacities squarely on the table. Judith Sargent Murray’s “On the Equality of the Sexes” (1790), published in the Massachusetts Magazine when women’s publication was still rare and often condemned, demanded to know the empirical basis for assertions of female inferiority. “Is it indeed a fact, that she hath yielded to one half of the human species so unquestionable a mental superiority?”Footnote 54

Because it remained difficult to argue for women’s civic participation and education as an end in itself, women instead pointed out that the need to educate republican men for citizenship required schools for future mothers.Footnote 55 Female academies for young women were founded beginning in the 1780s. Some of the earliest included Sara Pierce’s Litchfield Academy, founded in 1792 in Litchfield, Connecticut. They offered a curriculum designed to educate both “reason” and “the affections.” Though making concessions to female capacities to reason, the academy curricula offered a different array of courses to that of male-only colleges such as Harvard and Yale. Few offered Latin and Greek (which were thought to be virilizing preparation for citizenship, and therefore inappropriate for girls), and they generally focused on geography, arithmetic, history, French, and needlepoint.Footnote 56 Some of the first publications just for women, such as the Lady’s Magazine, offered a mashup of news, fiction, and reprints of European and American publications. These included the radical British writer Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which had extended the idea of rights to women, arguing for their legal, social, and educational disabilities under current practices. Still, after the revolution, a backlash occurred that reasserted female difference in both body and mind, stalling claims to equal rights of citizenship for many decades to come.Footnote 57

Revolution

During the late eighteenth century, the word “revolution” changed political meaning. In the past it had usually meant a cyclical return to a political origin point, as when the Earth has completed its journey around the Sun. In the theories of Aristotle and Polybius, the three kinds of government – monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic – all eventually degenerated into their baser versions (tyranny, oligarchy, and mobocracy), at which point the cycle of politics would begin anew. But beginning in the later eighteenth century, the term “revolution” began to refer much more often to the forcible establishment of a wholly new form of government, and even a new social and cultural order.

What made a revolution revolutionary was this new horizon of possibility, the sense that time itself was accelerating into a better tomorrow.Footnote 58 New mottos captured the temporal rupture: the American Revolution’s “Novus Ordo Seclorum” (new order of the ages) and the French Revolution’s “ancien régime” to refer to the era before 1789. The Abbé Raynal declared that the American Revolution fundamentally ruptured history itself. “The present is about to decide upon a long futurity,” he wrote in The Revolution of America (1781). “All is changed … A day has given birth to a revolution. A day has transported us to another age.”Footnote 59 The first history of the American Revolution written by an American – David Ramsay’s The History of the American Revolution (1789) – also announced the opening of “an Era in the history of the world, remarkable for the progressive increase in human happiness!”Footnote 60

In On Revolution (1963), the political theorist Hannah Arendt equated this new meaning of revolution with modernity itself. “Historically, wars are among the oldest phenomena of the recorded past while revolutions, properly speaking, did not exist prior to the modern age; they are among the most recent of all major political data.”Footnote 61 Yet the major political data of revolutions are not always transparent. Amid the bombastic rhetoric of new nationalism, Americans quietly expressed ambivalence and doubts about whether republicanism in fact yielded enlightenment. The US House of Representatives spent precious hours debating the matter in 1796. Some representatives hoped to announce to Europe that the United States was the most enlightened nation in the world. Others declared that idea a fool’s errand. Not only would it irritate more militarily powerful European powers, but they could not agree on which “political data” would in fact confirm that the United States had achieved enlightenment through republican government.Footnote 62

One data point was clear: the ongoing political importance of monarchy. Thomas Paine had relegated monarchy to a mist-shrouded barbaric age in Common Sense. But, in fact, nearly all of Europe and the Americas were still governed by monarchs, and would be for many decades to come. “American Ministers are acting in Monarchies, and not in Republicks,” John Adams noted correctly from Paris in 1783.Footnote 63 Nor were those monarchies the sinister agents of barbarity on which American revolutionary propaganda rested. Quite the opposite. For centuries, European monarchies had often acted as major cultural and intellectual brokers. They sponsored scientific societies, museums of all kinds, and patronized individual artists and intellectuals. A glance backward into their own history would have revealed to Americans that King George II had helped to found four universities: three, including Princeton, in his North American colonies; and one at Göttingen in his Germanic territories. This fact was conveniently forgotten amid revolutionary iconoclasm, when republican names replaced royal ones (as when King’s College became Columbia).

And lacking a clear sense of what a republican executive should look like, Americans also observed the recent phenomenon of enlightened despotism with interest. Emerging from divine-right monarchy, eighteenth-century rulers such as Catherine the Great of Russia, Charles III of Spain, Gustav III of Sweden, the Holy Roman Empress Maria-Theresa, and Frederick the Great of Prussia all to varying degrees adjusted their mandate to the intellectual climate of their era. They claimed – by their actions, publications, and policies – that it was possible to mix formidable executive power with reforms aligned with the new ideal of enlightenment.Footnote 64 They reformed law codes and criminal justice, encouraged greater religious toleration, restructured education, and promoted arts and culture. To Americans watching from across the Atlantic, these monarchs provided widely known, dynamic, modern examples of how to mix monarchical rule with the new goal of enlightenment. Unlike the absolutist monarchs of the previous century, who could swat away kingless republican rule as a momentary infatuation, enlightened despots operated in an era when popular opinion and republican government were becoming lived realities.

Nowhere was Americans’ serious interest in enlightened despotism clearer than in their admiration of Frederick the Great of Prussia, the war hero, political philosopher, and reformer. During his nearly half-century reign, from 1740 until his death in 1786, King Frederick became a relentless public advocate for enlightened reform engineered through powerful monarchical rule. A scholarly ruler who collected philosophers like butterflies at his Prussian palace Sans Souci, Frederick the Great published numerous works on his version of enlightened monarchical rule that were read by revolutionary Americans seeking to build a republic for the age of enlightenment. He read Rousseau on the social contract, Montesquieu on mixed government, and corresponded frequently with Voltaire, and even co-authored a refutation of Machiavelli’s The Prince (called The Antimachiavel) that was widely read by Americans. Frederick’s main platform, expressed in his Antimachiavel and elsewhere, was that a powerful, virtuous monarch could promote the state and the enlightened well-being of his subjects within the context of single-person rule.Footnote 65 Americans pondered this species of executive as they set about inventing the monarch-like presidency from whole cloth in Article II of the Constitution.Footnote 66

Frederick’s Prussia was the context for what has today become the most celebrated manifesto of enlightenment: Immanuel Kant’s “An Answer to the Question, What Is Enlightenment?” (“Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?,” 1784). This essay was unknown to revolutionary Americans, as Kant himself largely was until the early nineteenth century. But the essay’s core questions were both familiar and relevant to them: under what political conditions does a people emerge from a state of intellectual dependency to one of independence and enlightenment? Which species of government was best aligned with the goal of enlightenment? Over the next decades, an answer to the question of “what is enlightenment?” remained elusive as Europe and the Americas lurched from monarchy to republicanism and back again. “What is enlightenment?” one of Kant’s exasperated contemporaries wondered. “This question, which is almost as important as what is truth, should indeed be answered before one begins enlightening! And still I have never found it answered!”Footnote 67

By the 1780s, the new dream of enlightenment had already created a particular story of America’s break with Britain. This event, now called the “American Revolution,” would be no local rupture but instead a new order of the ages, a world-historical event in the grand ascent of universal human rights. The new United States would “illumine the world with truth and liberty,” declared the Connecticut minister Ezra Stiles in 1783. “This great american revolution, this recent political phænomenon of a new sovereignty arising among the sovereign powers of the earth, will be attended to and contemplated by all nations.”Footnote 68

Yet even as the new interpretative frame of the “American Revolution” settled into place by the 1780s, doubt, ambiguity, and open-endedness lingered. This can be difficult for us to see, given our commitment to finding a “real” American Revolution, a brute fact independent of interpretation, awaiting only our discovery, as though we had finally freed ourselves from the progressive interpretation of history embedded in the very idea of an “Age of Atlantic Revolutions.” Immanuel Kant captured the uncertain frame of mind by putting a question mark at the end of his title. In his final letter before his death, Thomas Jefferson turned to the progressive tense to describe the unfinished project of enlightenment in America. “All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man,” he wrote in 1826. “The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God. These are grounds of hope for others.”Footnote 69

Jefferson recognized that there were grounds for hope. But eyes were still opening. Enlightenment had not yet been achieved.