Introduction

The early modern period witnessed discoveries of new worlds, both literally and figuratively. As Europeans began to venture around the globe, they came into contact with peoples previously unknown to them. At the same time, ancient European cultures—classical as well as ‘barbarian’—attracted increasing interest concurrently with developments in scientific thinking and practice, which started to reveal new dimensions of reality, including a dawning new understanding of the human past. The European expansion marked increasing encounters with ‘otherness’ which arguably fostered antiquarian research: the interest in the origins and roots of people was a response to the cultural confusion that ‘exotic’ peoples, cultures and places in the ‘New World’ sparked off in Europe (Ryan Reference Ryan1981). While these new worlds were predominantly encountered outside Europe, the unknown and exotic northernmost fringe of the European continent—northern Fennoscandia—also stirred up imagination and fascinated European minds similarly to the ‘new worlds’ overseas, and emerged as a scene of exploration and subject to a ‘colonialist gaze’ in diverse forms. In addition to its natural and supernatural wonders, northern Fennoscandia was the homeland of the indigenous Sámi people, who became subject to a substantial interest especially from the seventeenth century onwards (see Byrne Reference Byrne2013; Davidson Reference Davidson2005).

When the first ‘ethnographic’ treatise of the Sámi people, Lapponia by Johannes Schefferus (1621–79), was being produced in Sweden in 1673 (Schefferus Reference Schefferus1956), antiquarian research was also consolidating in the country (see Baudou Reference Baudou2004, 55–105). By modern standards, early modern antiquarians knew very little about ancient cultures, classical or otherwise, and their visions of the past worlds can appear fabulous and even downright strange today, as illustrated by the ‘alternative histories’ that scholars weaved in seventeenth-century Europe (Burke Reference Burke2003). The so-called ‘Gothicist’ historiography in Sweden is a well-known example of such alternative histories; it provided the country and the nation with a glorious vision of the past that matched the hubris of the aspiring Swedish empire during its era of greatness. The past mattered in early modern Europe because it was thought to legitimize the present (Burke Reference Burke, Porter and Teich1992, 16; Stolzenberg Reference Stolzenberg2013, 20). In this setting, it is easy—and tempting—to think that Gothicism was about more or less conscious manipulation and misrepresentation of the past for political and other purposes on the one hand (e.g. Åkerman Reference Åkerman1991, 117), and about limited ‘true’ knowledge about ancient times on the other. While there is some truth to these views, a host of other factors are equally relevant to developing a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the seemingly peculiar ideas and representations of the past in the early modern period. In particular, it is critically important to consider the period visions of the past as embedded in the broader cultural and cosmological setting of the Renaissance and Baroque world.

This article examines the intersections of nationalism, colonialism and classicism in relation to early antiquarianism in early modern Sweden through the case of an alleged runestone reported from Pajala, Swedish Lapland, in the late seventeenth century. The monument first attracted the attention of the famous Uppsala professor Olaus Rudbeck (1630–1702), and has since been seen, interpreted and signified in various different ways; among others, it has been associated with the invention of writing, seen merely as a natural rock, and hypothesized as a possible Sámi sacrificial site. The early scholarly perceptions of the stone unfolded in a thoroughly Gothicist intellectual context, but treating the Vinsavaara stone (Sw. Vinsastenen)—or any other specific site, monument or object to that matter—simply as yet another instantiation of the Gothicist ideology is too superficial, narrow and generic.

A more deeply and widely contextualized approach is called for to appreciate how and why the monument came to have particular meanings. Interpretations of the Vinsavaara stone must be considered in the light of its materiality and landscape setting and within the broader framework of how the northern fringes of Fennoscandia were perceived in the heartlands of Scandinavia and Europe in general. There were myriad ideological, political and economic interlinks between nationalism, colonialism and classicism in the seventeenth century, and these connections are important to understanding early antiquarian thought and practice in Sweden. This entire complex, in turn, must be considered as embedded in the Renaissance/Baroque cosmology which defied various modern concepts and categories, and also affected understanding of the past–present relationships, or the relationships between ancients and moderns. This is the broader background against which the case of the Vinsavaara stone is discussed in the article.

A brief history of the Vinsavaara stone

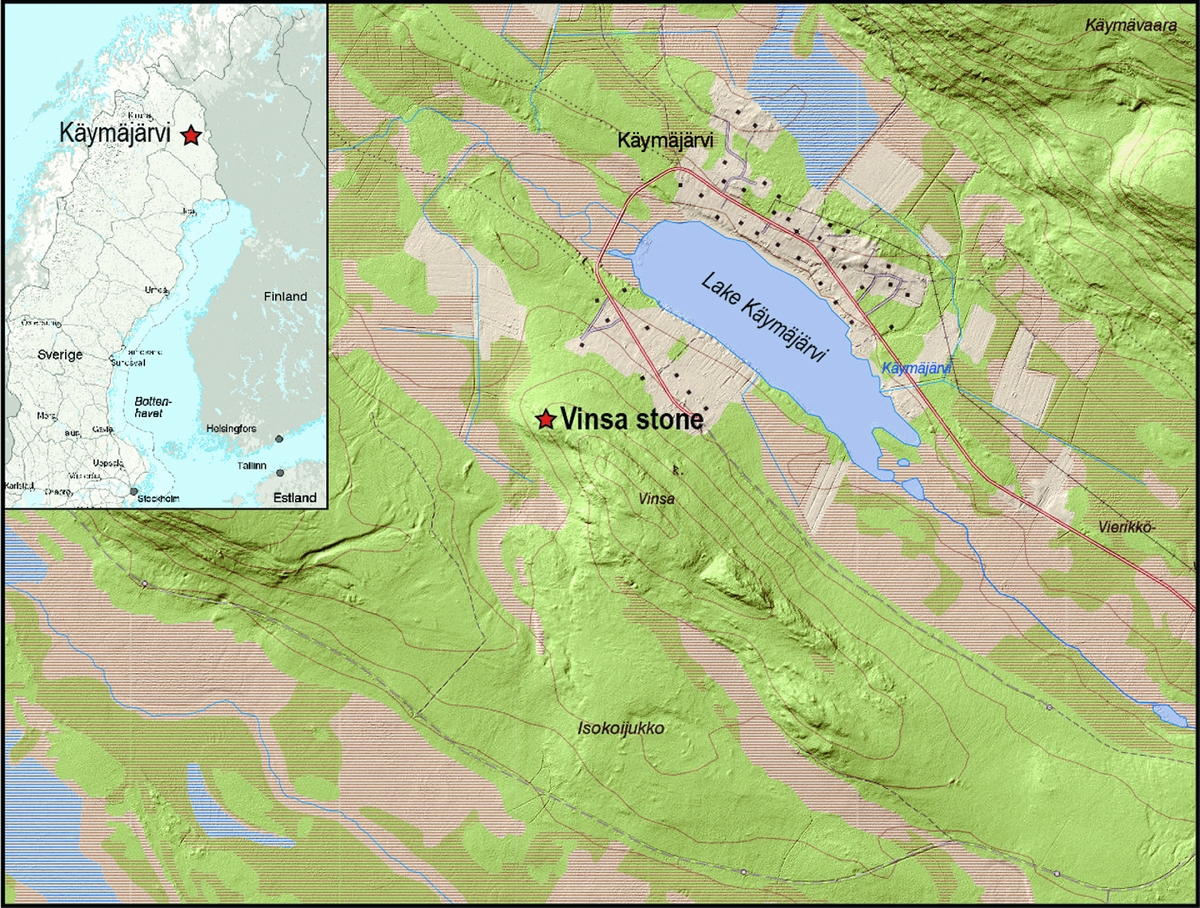

In 1687, the professor and polymath Olaus Rudbeck the elder, of the University of Uppsala, heard of an enigmatic monument located in the small village of Käymäjärvi in the northern wilderness of Sweden (Fig. 1). The stone reportedly had runic text and three crowns (the heraldic symbol of Sweden) inscribed on it, and Rudbeck envisioned the monument as yet another piece of evidence testifying to the great past of his fatherland, which he himself was in the process of chronicling in his magnum opus, Atlantica (Atland eller Manheim), published in four volumes in 1679–1702. A runestone far in the north—well beyond the Arctic Circle and at a much higher latitude than any other runestone in Sweden—was exciting enough to persuade King Carl XI of Sweden (r. 1660–97) to fund an expedition to document and study the stone. A party of three men—Johan Hadorph the younger (1630–93) and Johan Peringer (1654–1720), accompanied by a servant—embarked on a laborious trip to the north later the same year and returned with documentation that described the unidentified script and the three crowns on the stone located close to the crest of the hill called Vinsavaara. Rudbeck acknowledged the monument in the second volume of Atlantica, albeit only vaguely, but this nonetheless gave a birth to a half-mythical ancient monument which has since continued to provoke imagination for over 300 years (see Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011).

Figure 1. Location of the Vinsavaara stone in northern Sweden and its local topographic context.

A decisive step in the immortalization of the Vinsavaara monument was taken some four decades after the first antiquarian expedition to the site. The short-lived Swedish empire collapsed at the beginning of the eighteenth century and the seventeenth-century Gothicist fantasies of a great Swedish past became redundant with the end of the ‘era of greatness’. The enigmatic stone on Vinsavaara, however, continued to be remembered in the River Tornio valley, and it captured the interest of the famous French scientist Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698–1759), who directed an expedition to the Tornio valley in 1736–37 on a mission to determine the shape of the earth. On hearing about the Vinsavaara monument, Maupertuis decided to pay a visit to the site, accompanied by the famous Swedish naturalist Anders Celsius (1701–44), who had a keen interest in runes. The two men made drawings of the marks that they identified on the surface of the stone, but failed to make sense of them or to find the alleged crown carvings on it. Yet Maupertuis did not entirely dismiss the possibility that the stone was an authentic relic from the deep past, but continued to reflect on it, unable to decide whether it was just a curious work of nature or a very ancient artefact (see Pekonen & Vasak Reference Pekonen and Vasak2014, 192–3).

The Vinsavaara stone never later gained similarly high-profile attention, but neither was it forgotten. In the 1880s, for instance, a schoolmaster from the northern Swedish town of Luleå visited the site and concluded that the ‘runes’ were a product of weathering (Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011, 104). Some decades later, Schück (Reference Schück1933) wrote a short article about the curious case of the Vinsavaara stone, which has also more recently been subject to some historiographical interest (Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011). The Swedish Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) has defined the Vinsavaara stone as a natural rock with folklore associated with it (Riksantikvarieämbetet: Norrbotten, Pajala, Käymäjärvi, http://www.fmis.raa.se/cocoon/fornsok/). The stone still continues to spark off scholarly and popular speculations about its ‘true’ nature. The historian Osmo Pekonen and Juha Pentikäinen, a specialist in northern religions, visited the site in 2005 and were left puzzled by what they saw: could there be something special about the stone after all—could it perhaps be an ancient Sámi sacrificial site (Pekonen Reference Pekonen2005)? In popular ‘alternative historical’ readings, the Vinsavaara stone continues to be regarded as an authentic ancient monument (e.g. Nieminen Reference Nieminen2015, 198; see also Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011).

The geological context of the Vinsavaara stone

The fame resulting from the peculiar appearance of the Vinsavaara stone can at least partially be traced back to the geological environment of the Käymäjärvi region, which is quite atypical to the Norrbotten area. The region is a part of the Palaeoproterozoic Fennoscandian Shield and is located in its Norrbotten lithotectonic domain (Grigull et al. Reference Grigull, Berggren and Jönsson2014, 8). The Käymäjärvi site belongs to the western part of the area, the Kaunisvaara domain, a Palaeoproterozoic formation consisting mainly of basic volcanic rocks that have been metamorphosed to at least greenschist fascies (Grigull et al. Reference Grigull, Berggren and Jönsson2014, 7; Padget Reference Padget1977, 10–11). These so-called Karelian greenstones divide into two formations, the Käymäjärvi formation and the Vinsa formation (Martinsson & Wanhainen Reference Martinsson and Wanhainen2013, 32–3). The latter takes its name from the Vinsa ridge, on which the Vinsavaara stone is also located.

The Vinsa formation is composed of four members roughly synchronous with the Svecokarelian orogeny and hence c. 2.05–1.96 billion years old. The topmost member of the formation, M4, is a c. 150–200 m thick layer of dolostone, i.e. magnesium-bearing carbonate rock (Grigull et al. Reference Grigull, Berggren and Jönsson2014, 10, table 1) containing c. 22–22.5 per cent magnesium and 29.1–29.8 per cent calcium (Martinsson & Wanhainen Reference Martinsson and Wanhainen2013, 33). The association of Vinsavaara stone with member M4 and its identification as a substantially large block of dolostone was confirmed with an in situ chemical analysis performed with Bruker SD-IV portable XRF-analyser using the manufacturer's standard geological calibration (GeoQuant).

When approaching the Vinsavaara stone as a block of dolostone in a geological setting characterized by both metamorphism and tectonic processes, its sides that were interpreted to carry marks of ancient human intervention(s) quite obviously result from a complex sequence of natural processes. Fortunately, the immediate environs of the Vinsavaara stone in the Käymäjärvi region have received both early and very recent attention from Swedish geologists (e.g. Bergman et al. Reference Bergman, Hellström and Ripa2015, 7–9; Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Fjellström, Lundqvist and Niva1984, 3–5; Martinsson & Wanhainen Reference Martinsson and Wanhainen2013, 31) due to iron-rich skarn intrusions as well as copper deposits present in the area.

Closer examination of the Vinsavaara stone shows that, in contrast to normal carbonate rocks, the block has weathered unevenly, resulting in protruding, near-horizontal layers alternating with layers of more thorough weathering. This is typical for limestone and dolostone located near skarn environment (Kihlsted et al. Reference Kihlstedt, Broman, Alm and Siira1973, 3) and the skarn alteration in carbonates of the Vinsa formation (Grigull et al. Reference Grigull, Berggren and Jönsson2014, 24) shows that they had been exposed to metasomatism altering the host rock.

Tectonic history is the other factor explaining the appearance of Vinsavaara stone. The Vinsa ridge is a north-northwest–south-southeast-oriented overturned anticline (Grigull et al. Reference Grigull, Berggren and Jönsson2014, 13, fig. 5) with the strike forming a c. 15° dip, while an east-southeast-oriented folding axis and a northeast-oriented lineation, both with an identical dip of 15°, have been located south of the Vinsavaara stone (map: SGU 1977). Thus, rather than runes or another type of script recording the hidden past of the Sámi, the block of dolostone carries the record of various tectonic events that the Vinsa formation has undergone. The third factor contributing to the current state of the Vinsavaara stone is weathering that has continued to alter its appearance since it was documented for the first time in the 1680s (Tobé Reference Tobé1999, 40).

Documentation and description of the Vinsavaara stone

The stone is an approximately 2×3 m dolostone slab which is about 80 cm high (Figs 2–3).Footnote 1 Most of the slab, especially the part facing the upper ridge, is covered with vegetation. On the sector extending from southwest to southeast, however, the rock face is exposed and can be divided into four sharply defined rock faces, A–D.

Figure 2. The Vinsavaara stone in its local landscape setting.

Figure 3. The ‘main face’ of the Vinsavaara stone today.

Rock face A is oriented to 225° and is a c. 1 m wide and 70 cm high surface tilted 38° inwards. The surface is clearly layered; the layers are tilted downwards 30° to the right. Some of the layers are wider, c. 4–6 cm thick, and the rune-like grooves coincide with these layers. These grooves are tilted c. 15° to the right with respect to the orientation of layers. Within and between thicker layers one can observe narrow lamellae that protrude c. 0.5–1 mm from the rock surface. In addition, a few c. 3–4 cm wide and 4–5 cm deep oval hollows are visible on the surface. The layered structure is interrupted by a zone of hollow vertical gashes that are c. 10 cm high and 2 cm wide. The long exposure of the rock face A to the forces of nature is indicated by a dark patina covering it completely.

Rock face B is oriented roughly perpendicular to face A with an orientation of 305° and is about 50×50 cm in size with the surface tilted 25° inwards. The surface is not as pronouncedly layered as in rock face A, but nevertheless small protruding lamellae can be detected that cover practically the whole surface. The layers are tilted 12° upwards to the right. On this side the c. 3 cm high ‘rune-grooves’ are more pronounced and either vertical or diagonal in orientation. Therefore it is very likely that the early explorers visiting the Vinsavaara stone focused their attention on and documented these grooves as runes.

Rock face C is oriented roughly perpendicular to face B with an orientation of 235° and is about 40 cm wide and 30 cm high. The surface is tilted 35° inwards and completely covered by patina resulting from weathering. It is quite similar in appearance to rock surface B, but completely lacks markings that could have been mistaken for runes.

Rock surface D is oriented towards 305°, hence it is roughly perpendicular to rock surface C. It is an approximately 1.5 m wide and 80 cm high surface, which has recently been partly exposed by clearing off the moss and other vegetation. Therefore, this surface is substantially fresh and offers the best source for examination of the Vinsavaara stone's physical and chemical composition. The former aspect was studied by visual inspection, while the latter was explored with in situ analysis carried out with a Bruker SD-IV portable XRF spectrometer.

The Vinsavaara stone is characterized by 2–6 cm thick layers of beige dolostone with alternating thinner layers of light grey rock containing somewhat elevated quantities of silicon, potassium and iron with substantially lower quantities of calcium and phosphorus. The silicon content is also higher in protruding lamellae, which indicates the presence of weather-resistant mineral like quartz and the rock face also shows rare patches of whitish limestone. The surface is also characterized by horizontal, vertical and diagonal cracks that bear witness to the complicated geological history of the Käymäjärvi area. Similar features in dolostone have been documented from other parts of the world, and they can be seen in other rock exposures around the Vinsavaara stone itself.

In all, the Vinsavaara stone can be interpreted solely as a natural formation that is a result of local geology, tectonic history and weathering. While the outcome is unquestionably quite peculiar and intriguing, the rock does not show any trace of human intervention. However, this result does not undermine the historical significance of Vinsavaara stone in seventeenth-century Swedish nation building. The presumed significance of the stone to the Sámi people, on the other hand, is a more difficult question to answer without carrying out archaeological excavations around the stone. A low moss-covered cairn or heap of rocks was identified some metres from the Vinsavaara stone, but its nature is currently unknown.

Cultural affiliations of the Vinsavaara stone

Geological factors explain the ‘inscription’ on the Vinsavaara stone and may be considered integral to how the site was more generally perceived by the locals and learned visitors in the early modern period. For people familiar with the region, the stone and its surroundings would have appeared as a somewhat special location in the landscape especially due to the presence of peculiar-looking dolostone blocks (Fig. 4), of which the Vinsavaara stone itself is the most prominent example. Dolostone is untypical to northern Fennoscandian landscapes and, based on our walks at the site, clearly observable on the surface only in a limited area, which thus comprises a noticeable discontinuity in the landscape. Places of discontinuity and anomalous landscape elements often attract cosmological or other cultural meanings in pre-modern cultures (Knapp & Ashmore Reference Knapp, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999), which was also the case in northern Fennoscandia.

Figure 4. A dolostone slab near the Vinsavaara stone. Some slabs, although natural, are rather regular in form and look as if they had been shaped by people.

It is well known, for instance, that Sámi sacred sites were frequently associated with prominent or anomalous landscape features (e.g. Äikäs Reference Äikäs and Silvonen2015), and it has been speculated that the Vinsavaara stone might also have been a Sámi sieidi (e.g. Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011, 99; Pekonen Reference Pekonen2005, 27). Northern Fennoscandia is the traditional homeland of the indigenous Sámi, but it had been subject to Finnish/Swedish resettlement for a long time before the discovery of the Vinsavaara stone, so it is not obvious to whom the site would have been of special significance. Both Rudbeck and Maupertuis nonetheless indicated that the stone was, or had been, locally meaningful, which presumably means that some local lore was associated with it, and this is also probably the reason why the stone came to attract antiquarian interest in the first place (Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011). While the Vinsavaara stone can, in principle, be an (old) Sámi sieidi, it is equally possible that the stone, as a peculiar landscape element, was a locus of Finnish/Swedish belief and tradition (Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011, 99). Finnish folklore proposes that ‘spiritual’ dimensions were commonly associated to diverse landscape elements—such as particular trees, bodies of water and geological formations (see, e.g., Sarmela Reference Sarmela1994)—and the curious Vinsavaara stone may well have promoted folk beliefs, whether these were actively held in the late seventeenth century or were a part of local memory (see also Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011, 99).

Rudbeck and Maupertuis reported that the locals believed the stone to contain secret (ancient) knowledge (Pekonen Reference Pekonen2005, 26). This strikes a resonance with contemporaneous scholarly ideas of runes, which were regarded not only as alphabets, but also as mysterious symbols charged with a magical potential that an adept could tap for such purposes as calling spirits and summoning the dead (Andersson Reference Andersson1997, 102; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2014, 307–62; Karlsson Reference Karlsson2009, 71–2). The study of languages, scripts and symbols was a thriving field which appeared to provide new perspectives on the histories of nations, and this pursuit—like antiquarian studies at the time in general—was not without mystical and esoteric dimensions (e.g. Åkerman Reference Åkerman1991, 110–12; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2014, 307–62; Stolzenberg Reference Stolzenberg2013, 19–23; see also Nagel Reference Nagel2011; Wood Reference Wood2008). With their unknown origins and age, runes appeared a particularly enigmatic script and were subject to considerable scholarly interest in seventeenth-century Sweden (King Reference King2005, 194). Following the lead of Johannes Bureus (1562–1652) and his rune mysticism, Rudbeck asserted that runes comprised the most ancient writing system in the world, one from which the Greek alphabet was derived (Ekman Reference Ekman1962, 61; King Reference King2005, 198). Although he did not mention the Vinsavaara stone directly, Rudbeck referred to Peringer's and Hadorph's trip in the second volume of Atlantica and argued that runes had first been conceived in the North, ‘up there, above Tornio’ (Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011, 101). Regarding their mystical properties, runes were thought of in similar terms to Egyptian hieroglyphs; indeed, Rudbeck himself looked into hieroglyphs in his attempts to make sense of runestones and understand the ancient world (Eriksson Reference Eriksson2002, 441, 560–61).

The idea of writing originating in Scandinavia and the mixing of ancient cultures—of widely different ages and geographical regions—may appear peculiar in today's view, but they were embedded in broader visions of the North as the homeland of civilization on the one hand, and more fundamental early modern relational concepts of space and time on the other. The Renaissance–Baroque understanding of reality permitted the linking, blending and overlapping of times and places in a non-linear and non-historicist manner, so that artefacts existed simultaneously in different time horizons, ‘pulling together different points in the temporal fabric until they met. By means of artifacts, the past participated in the present’ (Nagel & Wood Reference Nagel and Wood2005, 408). The esoteric and magical aspects of antiquarianism, including the study of ancient languages and scripts, must be considered within this broader cosmological view in which reality was pregnant with correspondences, analogies and sympathies (e.g. Herva Reference Herva2010; Karlsson Reference Karlsson2009, 212–13; Livingstone Reference Livingstone1988, 277; Thomas Reference Thomas1971, 337–8). This also made it possible to connect with past worlds and bring something of them back to life (see Godwin Reference Godwin2002).

In this intellectual setting, the mysterious inscription was likely the main element that invested the Vinsavaara stone with a sense of a living past in the present (cf. Herva & Nordin Reference Herva and Nordin2015, 130), but dolostone as a material would have amplified, even if subconsciously, the association of the stone with ancient civilizations in scholarly imagination (Fig. 4). The learned visitors of Vinsavaara did not specifically comment on the materiality of the stone, but they undoubtedly identified it as limestone, which is closely related to marble—and marble, in turn, had strong associations with classical antiquity (see below). Indeed, it is interesting to note (whether or not it had anything to do with the materiality of the stone) that Maupertuis explicitly compared the Vinsavaara stone to classical monuments. He mused that while the stone lacked the beauty of Graeco-Roman monuments, the inscription, if indeed it was man-made, would be the oldest in the world and work of a disappeared civilization (Pekonen & Vasak Reference Pekonen and Vasak2014, 191).

The classical world loomed large in the learned early modern European mindscapes and was a ‘naturalized’ epicentre of antiquarian discourses, as well as an anchor point for the understanding of the past in general; and limestone as a substance perhaps prompted (however subtly and probably subconsciously) an association between the Vinsavaara stone and ancient times. Although not the shiny marble of Greek and Roman monuments, limestone was nonetheless similar to it and thus perhaps readily resonated with cultural ideas of Atlantis and ‘disappeared civilizations’ associated with ancient Mediterranean cultures. Marble was a powerful symbol both of classical antiquity (see Greenhalgh Reference Greenhalgh2008, 3–5, 8, 26) and its Renaissance appropriation in architecture and sculpture, as exemplified by Michelangelo's David fashioned out of Carrara marble. The long-term use of marble sources was in itself a form of creating a cultural continuum and meaningful connection between the classical and early modern world (Barkan Reference Barkan1999, 331). Indeed, marble as a material had cultural associations with a deep past (Greenhalgh Reference Greenhalgh2008, 3–5, 8, 26), and this cultural aura of marble may, on some level, have also affected the reception of the Vinsavaara ‘monument’ in the intellectual climate of the seventeenth and eighteenth century.

Juxtaposing classical and northern worlds

The early modern perceptions of the Vinsavaara stone were embedded in broader classicizing narratives of northern pasts, or identifying connections between northern and classical worlds. This classicizing took various forms in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Sweden. Classical themes, motifs and styles were imitated in, for example, urban planning and architecture especially from around the mid seventeenth century onwards, whereas linguists and antiquarians were uncovering the connections between Scandinavian and classical languages, mythologies, religions, histories and geographies (see e.g. Herva & Nordin Reference Herva, Nordin and Watts2013; Reference Nordin, Leone and Knauf2015). Johannes Messenius (1579–1636), for instance, first proposed that the Hyperboreans in classical accounts referred to Swedes (Anttila Reference Anttila2014, 31) and many others operated within a similar framework of thought. It was on this broader classicizing discourse that Rudbeck the elder's work built.

Swedes claimed classical heritage through their alleged descent from the Goths whose origins were traced to Scandinavia on the basis of classical accounts. In the nationalistic Swedish narrative, the Goths were the original bearers of civilization from whom the Greeks and subsequently the Romans learned Nordic wisdom. Thus, classical heritage became but an aspect of Gothic heritage and the seventeenth-century Swedish appropriation of the ancient world hybridized Graeco-Roman and ‘barbarian’ themes. ‘Both’, as Neville (Reference Neville2009, 215) points out, ‘were different facets of antiquity’. This conflating of different times and cultures, as well as mythical and historical elements, took diverse rhetorical and material forms in seventeenth-century Sweden. Queen Christina, for instance, presented herself as Pallas Athena and identified closely with Alexander the Great (Biermann Reference Biermann2001; McKeown Reference McKeown2009, 149). Her father Gustav II Adolf posed himself as a mythical king of the Goths in Roman-style clothes in his coronation; similarly King Carl IX later had some of his courtiers dressed in Roman clothes while addressing them as Goths (Neville Reference Neville2009, 215; Ringmar Reference Ringmar1996, 108–9, 116).

One of these themes with a classical pedigree that were developed in the context of the Vinsavaara stone was the assumed significance of the sun to northern peoples and cultures. Upon requesting funding for the Torne expedition, Rudbeck reflected that the stone was located ‘where our eldest forefathers observed the movements of the sun and the moon’ (quoted in Pekonen Reference Pekonen2005, 24: our translation). He believed that sun worship had been practised at this particular site because it was located on the latitude which marked the southern border of the true polar day where the sun stayed above the horizon in the summer (Enbuske Reference Enbuske, Ikäheimo, Nurmi and Satokangas2011, 101).

The notion that the ancient religion of northern peoples revolved around sun worship derived from classical antiquity. The Greek geographer Hecataeus of Abdera, for instance, offered a description of Hyperborea located on an island beyond the North Pole, and its inhabitants devoted to Apollo in his role as sun-god (Diodorus Siculus Reference Oldfather1935, 2.47; Davidson Reference Davidson2005, 23–4). The association of northerners with Apollo is not coincidental in that there is a classical tradition that regards Apollo as a Hyperborean god originating in the North, as reflected in, for instance, his ‘northern’ emblems amber and the whooper swan (Ahl Reference Ahl1982; Davidson Reference Davidson2005, 24). Rudbeck embraced this notion of Hyperborean Apollo (Eriksson Reference Eriksson2002, 257–78; King Reference King2005, 171–2) in the footsteps of other antiquarians, such as Johannes Bureus and Olaus Verelius, who had argued for the northern origins of classical deities, for instance forging a link between Odin and Apollo (Anttila Reference Anttila2014, 58, 71, 106–11, 125; see also Håkansson Reference Håkansson2012). The suggested special relationship between northerners and the sun was at least partly linked to the notion of Lapland as the land of the midnight sun in the early modern world, but it also resonated with the classical idea of the sun residing in an (undefined) North and with northerners during the Mediterranean night (Davidson Reference Davidson2005, 23–4).

In more general terms, the North and northern lands have provided a canvas for cultural imagination and projections since the dawn of European history. A mythical Hyperborean land located beyond the north wind (Boreus/Boreas), as first described in Homeric hymns and classical geographical accounts, had characteristics which are found in (early) modern perceptions of the North: a rich utopian land of light and marvels on the one hand, and a dark barbarian world of death and evil on the other (Davidson Reference Davidson2005, 21–7). The North has been conceived in ambiguous and conflicting terms for centuries and millennia—a place of extremes and the exotic, a blend of realities and fantasies (see further Andersson Burnett Reference Andersson Burnett2010; Davidson Reference Davidson2005; Naum Reference Naum2016; Oliver & Curtis Reference Oliver and Curtis2015). The fact that northern Fennoscandia was effectively a terra incognita in the early modern European world enabled representing it in mutually different and conflicting ways. Moreover, the relative proximity of northern Fennoscandia to the European heartlands added to the confusion about the ‘place’ of the exotic North in European mindscapes (see Naum Reference Naum2016, 490), which resonated with the more general ‘existential’ confusion that the discovery of, and encounters with, the previously unknown worlds and peoples provoked in the early modern period (reflecting the confusing ‘spirit’ of the time). Yet another factor that promoted conflicted perceptions was a more general change of an attitude towards the North in the eighteenth century, when the exotic and threatening North was in the process of transforming from a place of magic and sorcery into a place of nostalgic longing for rapidly disappearing pre-modern lifeways in the face of modernization (Andersson-Burnett Reference Andersson Burnett2010).

The classical tradition also shaped early modern perceptions of the North and northern lands, eagerly embraced by Rudbeck and his predecessors, and came to be attached to actual northern Fennoscandian landscapes and culture more generally. Rudbeck identified a plethora of links between northern and classical Mediterranean cultures. Not only had runes been a model of the Greek alphabet, but he also argued, for instance, that Jason and the Argonauts had ventured all the way to the northernmost Baltic Sea, and that the Underworld described in the classical mythology refers to actual northern Swedish geographies (Eriksson Reference Eriksson2002; King Reference King2005). Although Rudbeck's Atlantica took ideas about the relationships between northern and classical cultures to an extreme, his vision was founded on the work and thinking of many other Swedish scholars. The Magnus brothers had, in the sixteenth century, laid a foundation to the alleged great history of the Swedish nation in Historia de omnibus Gothorum Sveonumque regibus (Johannes Magnus 1554) and Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Olaus Magnus Reference Magnus and Foote1998 [1555]). Johannes Bureus, for instance, had developed ideas similar to Rudbeck in arguing that Abaris Hyperboreos, a sage and priest of Apollo in the Greek classical tradition, was a Swede from whom Pythagoras learned philosophy, linking rune staffs to the wand of Abaris (Anttila Reference Anttila2014, 61; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2012, 511).

The Vinsavaara stone was just one example that was taken to indicate such connections between the northern world and ancient Mediterranean civilizations, and it illustrates how the attraction to the classical past and the North dovetailed in the early modern world. Fascination with ancient Greece and Rome was, of course, a cultural leitmotif of the emerging modern world, and classical ideas about the North also became of interest in this broader context and in conjunction with the increasing Swedish and international attention given to the northern regions of Fennoscandia (as discussed in more detail below). The classicizing of the North did not operate only in the context of antiquarian discourses, or on an ideational and representational level, but took various material forms. These included classically inspired Renaissance spatial planning, architecture and material culture, all of which were enthusiastically adopted in the polite culture of Sweden—and across northern Europe—particularly in the seventeenth century (e.g. McKeown Reference McKeown2009; Neville Reference Neville2009; Ottenheym Reference Ottenheym2003).

Classicizing tendencies in cultural landscapes are in evidence also in Lapland/Sápmi from early on in, for instance, the spatial organization of the town that the Swedish Crown planned to found in Arjeplog and in the silver and iron works established following the discovery of silver ore in Nasafjäll (Nordin Reference Nordin2012, 150–59; Reference Nordin, Leone and Knauf2015; see also below). Indeed, this early influence of classicism in the North was hardly a coincidence, but is better seen as reflecting and nested in wider interests in the northern fringe of Fennoscandia and larger-scale historical processes unfolding in the early modern world. These involved, among others, the keenness of the Swedish elites to ‘Europeanize’ Sweden, which in turn was connected to the building of Swedish identity in a situation where Sweden was emerging as a European great power—a position that it achieved through warfare, which called for resources.

The North as a material and symbolic resource

While the early modern ideas of the Vinsavaara stone and its cultural context appear peculiar and out of place in today's perspective, they are in line with more general and longer-term European cultural fantasies and projections of the North and northern lands—both in a geographically unspecified sense and with particular reference to Lapland/Sápmi—from the classical world to the Age of Discoveries, Nazi Germany, and contemporary tourism industry. The centuries-long interest in the northern regions of Fennoscandia has taken diverse forms, such as dreams of imaginary and real riches, as exemplified by mining industries from the seventeenth century to the present, and scholarly curiosity in the northern world and its inhabitants, especially the indigenous Sámi people.

The resources of northern Fennoscandia already attracted the attention of the Nordic kingdoms and the state of Novgorod in the Middle Ages (Kuusela et al. Reference Kuusela, Nurmi and Hakamäki2016), when fish and fur were particularly wanted commodities. The interests in the northern fringe of Fennoscandia nonetheless consolidated and diversified in the early modern period when Lapland also begun to draw wider European attention. King Gustav Vasa claimed Lapland as part of the Swedish realm in the sixteenth century and the Swedish state expanded and tightened its control of the North in the following century, which also saw the first mining boom in Lapland after the discovery of silver ore in Nasafjäll (Nordin Reference Nordin, Leone and Knauf2015). Although a poor and peripheral country, Sweden was aggressively expansive in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and briefly became a northern European great power with successful involvement in the Thirty Years War (1618–48) in the lands of the Holy Roman Empire on the Continent.

As Sweden rose to a prominent position in the European political scene, the Swedish elites came to suffer from something of a cultural ‘inferiority complex’: their home country appeared to lack a distinguished past fit for a great power and cultural achievements comparable to those of more established European states (Ringmar Reference Ringmar1996). This state of affairs inspired, in part, antiquarian pursuits for discovering a glorious past for Sweden and promoted a range of ‘civilizing projects’ in the country, including its more peripheral and distinctively ‘undeveloped’ northern regions. Lapland/Sápmi thus emerged as an arena for the Crown's dreams of transforming an ‘uncultivated’ land and its ‘savage’ inhabitants into a civilized and productive part of the realm (see Naum Reference Naum2016). At the same time, a wider European interest in northern lands emerged as, for instance, the Dutch became closely engaged in Swedish mining industries while the exotic and exciting Lapland emerged as a prime destination of European travellers in conjunction with the decline of the Mediterranean-centred Grand Tour institution (Byrne Reference Byrne2013; Nordin Reference Nordin, Leone and Knauf2015). For foreigners, the North was primarily a matter of curiosity and exoticism, whereas the Swedish authorities had a utilitarian approach and were mostly interested in surveying the resources that Lapland had to offer (Naum Reference Naum2016, 495–6).

Early modern travellers had various reasons for venturing into the northern margins of Europe, but scholarly curiosity—as in the case of Rudbeck's and Maupertuis's expeditions—was one of the main motivations (Byrne Reference Byrne2013). Indeed, Swedish patriotic Gothicist fantasies of the North as a land of riches and glory promoted the idea, from the seventeenth century onwards, that the northern margins of the European world provided a remarkable resource for scientific research (Sörlin Reference Sörlin2000, 56–8). It is unsurprising, against this background, that the state supported excursions to the exotic and unknown Lapland, which was comparable to the early modern scholarly curiosity about the other continents (Sörlin Reference Sörlin2000, 58).

The support that the Rudbeck expedition gained from the King of Sweden was thus an instance of this larger scientific programme directed to the North, and the state support undoubtedly encouraged Peringer and Hadorph to see runic writing and the Swedish national emblem of three crowns on the stone. At the same time, however, the tedious travelling into unknown North in itself and the very experience of a half-mythical northern land—literally and symbolically something of an ‘otherworld’ where ‘Swedish and foreign visitors alike experienced a feeling of disorientation and unfamiliarity’ (Naum Reference Naum2016, 496)—mediated the reception and interpretation of the mysterious stone. That is, the experience of foreign lands and places is affected by the baggage of cultural assumptions that visitors bring with them. Travelling is a cultural practice, as tourism research has shown (e.g. Urry Reference Urry2002). Gothicist imagination on the one hand, and broader early modern ideas of the North on the other, comprised a framework within which the mysterious stone in the backwoods of Käymäjärvi was perceived.

The merging of myths and realities (as it would be understood in today's terms) characterized the study and understanding of the past in the seventeenth century. This is particularly clear and well known with regard to Rudbeck's scholarship, which, however, continued a Swedish scholarly tradition dating back to the late medieval period, and which not only traced the history of the Swedish nation back to the Goths, but rendered Sweden as the cradle of all civilization, as discussed above. In this view of history, all civilization could be traced to the Goths who were taken to be descendants of Noah's grandson, Magog. Following their settling in Sweden after the Flood, the Gothic tribe then wandered to the South, where they taught Scandinavian wisdom to the ancient Greeks (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2014, 510–11). Yet this line of thinking was not peculiar to patriotic Swedish scholarship either, but there was also a more generally held European view—which moreover outlived the Swedish era of greatness—that culture emanated from the North (see Byrne Reference Byrne2013, 41). Indeed, similar notions have been advanced in modern ‘esoteric’ and ‘alternative’ historical thinking, of which Nazi mythologies of the Aryan northern origins are an example (Godwin Reference Godwin1996).

The poorly known Lapland, then, was envisioned, from the sixteenth century to the Swedish era of greatness and well beyond it into the eighteenth, as a land of untapped material resources and riches in the form of agricultural expansion and a source of minerals and forest products, as well as even pearl fishing (Naum Reference Naum2016, 501–2; Nordin Reference Nordin, Leone and Knauf2015). Lapland, however, was envisioned and served as a resource of intangible and symbolic riches. It was a ‘promised land’ of scientific enquiry, a view that was initially founded on Gothicist fantasies, as represented by Rudbeck's scholarship, and was continued in a more sober form into the eighteenth century, of which Maupertuis’ expedition is an example (see also Sörlin Reference Sörlin2000). In other words, Lapland could be, and was, explored and exploited for glory, prestige and fame—it was a resource for constructing a Swedish history and identity. Antiquarian pursuits in the North, and the interest in the Vinsavaara stone as a part of it, were part of this symbolic exploitation of Lapland.

Colonialism and antiquarianism in Lapland/Sápmi

Although small-time agents in the global stage, Scandinavian kingdoms engaged actively in colonialist pursuits in the early modern period. Sweden, for instance, acquired an overseas colony in the Delaware valley in the 1630s, although it managed to hold on to it only for less than two decades before it was taken over by the Dutch in 1655. Less obviously, however, Sweden also imposed colonialist ideas and practices on northern Fennoscandia, the homeland of the indigenous Sámi. While conventionally ignored or overlooked in Scandinavian historical narratives, the Swedish perceptions of, attitudes to, and activities in Lapland/Sápmi were essentially colonialist in character, especially from the seventeenth century onwards (Naum & Nordin Reference Naum and Nordin2013). A colonialist view is reflected in, for instance, the Swedish statesman Carl Bonde's (1620–67) musings that Lapland could become ‘the West Indies of the Swedes’ and a source of great wealth (Bäärnhielm Reference Bäärnhielm1976; Naum Reference Naum2016, 493).

Various historical processes and phenomena in northern Fennoscandia can be framed in terms of colonialism, but the colonial situations and encounters in this northern margin of the European world were not necessarily similar in all respects to those in the New World. Northern Fennoscandia had been an arena for encounters and interactions between diverse groups of people of diverse cultural backgrounds for centuries before distinctively colonialist relationships between the different groups of people emerged in the seventeenth century (e.g. Kuusela et al. Reference Kuusela, Nurmi and Hakamäki2016). Although the Sámi did ultimately become singled out as the indigenous ‘Other’ and subject to distinctively colonialist attitudes and policies, it is the more general opposition of the southern ‘heartlands’ of Sweden and the northern ‘periphery’—or the subordination of the North to the South, a desire to take the North under the control of the South—that is central to understanding how the Vinsavaara stone came to feature in colonialist discourses in early modern Sweden.

Colonialism and classicism were often intertwined in the early modern world, and this was the case also in northern Fennoscandia (Gosden Reference Gosden2004, 112–13; Herva & Nordin Reference Herva, Nordin and Watts2013; Nordin Reference Nordin2013). The juxtaposition of colonialist and classicist themes can be seen rooted in the profound cultural confusions stemming from the break-down of the medieval order of the world with the Age of Discoveries, and a plethora of other socio-cultural developments that took place from the late medieval to the early modern period and significantly changed Europeans’ perception of their place in the world (Ryan Reference Ryan1981). On the one hand, European expansion around the globe brought them increasingly into contact with ‘Otherness’, as represented by peoples and cultures fundamentally different from the European world, which conceivably triggered the interest in roots and origins in the Old World, as expressed in the fascination with the ancient Graeco-Roman world (Ryan Reference Ryan1981, 532). Yet on the other hand, there was also a thematic connection between classicism and colonialism in the sense that, like the exotic cultures in far ends of the world, the Graeco-Roman world also represented a reality which was familiar, but at the same time deeply alien and different from the Renaissance European world (Ringmar Reference Ringmar1996, 146). This more general-level confusion is, as noted earlier, probably one reason why the North, which was unknown and yet known to be a land of extremes, attracted such ambiguous and conflicting perceptions in early modern Europe.

Classically inspired ideas and materialities, as imposed on early modern Lapland and its (imagined) pasts, can be seen as one means of the southern ‘conquering’ of northern Fennoscandia concretely and symbolically, irrespective of the immediate and conscious motivations for classicizing tendencies. Cartography and spatial planning were among the more specific tools grounded on the classical tradition and employed in the colonization of the North. The rise of map making and urban planning in the Renaissance was an aspect of the period's classicism and adopted in Sweden as a part of the wider adoption of Renaissance culture in the seventeenth century (see further Herva & Nordin Reference Herva, Nordin and Watts2013; Herva & Ylimaunu Reference Herva and Ylimaunu2010). Whatever functions and meanings they otherwise had, map making and urban planning served to order and regulate the world in a new manner, materially and conceptually. Both practices emphasized the separation of, and the boundary between, nature and culture, as well as the objectification and commodification of the environment, hence mediating a modern western way of seeing, categorizing and understanding the world (cf. Ingold Reference Ingold2000; Mrozowski Reference Mrozowski1999). This also came to strip the authority of situational and ‘indigenous’ knowledge and ways of knowing the world, which contributed to the disempowerment of the northerners subjected to the Swedish Crown's material and symbolic conquering of Lapland (see also Naum Reference Naum2016, 503).

A striving for regularity, symmetry and geometric order—as exemplified by the grid plan—characterized Renaissance urban planning (e.g. Akkerman Reference Akkerman2000). The grid plan was eagerly adopted in seventeenth-century Sweden and the Crown indeed sought to make orthogonal urban plans something of a norm from around 1640 onwards, as is most clearly reflected in the state-driven project of regulating urban spaces—more or less successfully—on a grid plan (Ahlberg Reference Ahlberg2005). At the same time, in 1638, Olof Tresk (d. 1645) was sent to conduct a survey of Lapland where silver ore had recently been discovered in Nasafjäll near the Swedish-Norwegian border, and the Swedish Crown was anxious to ensure its claim for this and other sources of wealth in the North (Naum Reference Naum2016, 491). Tresk's survey was but a part of a much more extensive map-making campaign that the Crown had launched with the founding of the Swedish land survey in 1628 (Baigent Reference Baigent1990). The surveying of Lapland, however, had been initiated already in the very beginning of the seventeenth century due to state interests in the trading and other opportunities that northern areas were seen to provide (e.g. Puhakka Reference Puhakka, Lamberg, Hakanen and Haikari2011).

There were potentially a number of both immediate and indirect reasons for the rather sudden and intensive interest in cartography and classically inspired geometrization of urban space in Sweden. It is notable, however, that these developments took place when the Swedish kingdom was expanding around and even beyond the Baltic Sea region and at the same time, as discussed above, struggling with a cultural inferiority complex stemming from its real and perceived marginalized position within the past and present European world. The arts of map making and spatial planning served, first, to realign Sweden culturally with the European world through appropriation of the classical tradition and, second, to contribute towards the unification of the expanding and internally heterogeneous realm (Herva & Ylimaunu Reference Herva and Ylimaunu2010). A consequence of these seventeenth-century developments was that Lapland/Sápmi became more tightly incorporated, symbolically and concretely, in the kingdom of Sweden and subjected to southern dominance and the Crown's control. This was manifested, for instance, in the intensified planting of Lutheranism and other ‘civilizing projects’ in the North, entangled with colonialist policies and practices (Naum Reference Naum2016, 491).

It is noteworthy, against this broader background, that the grid plan made a rather early appearance in the North. The grid plan has been employed in manifold socio-cultural and environmental settings over its documented history spanning three millennia, but it has recurrently been favoured in colonialist settings (Grant Reference Grant2001), which was also the case with the Swedish overseas colony of New Sweden in the Delaware valley. The first Swedish settlement in the region, associated with Fort Christina, was laid on a geometrical plan which was poorly adapted to the environmental realities of the marshy area around the mouth of River Christina (see, e.g., Dahlgren & Norman Reference Dahlgren and Norman1988, 168). Thus it can be compared to the Dutch Cape Town fortress which, as Mrozowski (Reference Mrozowski1999) points out, echoes a symbolic dimension of colonialist construction projects, namely manifesting domination over the local environment and conditions. As to Lapland, the silver-working sites at Silbojokk and Kvikkjokk, founded deep in the northern wilderness after the discovery of Nasafjäll ores, paralleled New World plantations in terms of spatialities, materialities and functioning (Nordin Reference Nordin2012; Reference Nordin, Leone and Knauf2015). Likewise, the colonial town that the Swedish Crown planned to found in Arjeplog would have been built on a geometrically regular grid plan and divided between Sámi and Swedish inhabitants (Nordin Reference Nordin2012, 150–59).

Antiquarian studies in the North unfolded in, and were part of, this colonialist setting. The poorly known northern land not only held a promise of material wealth, but also made it possible to discover ‘symbolic riches’, such as the claimed evidence of the earliest writing in the world, which could then be harnessed for re-envisioning the grand narratives of the past and the place of northern regions within those narratives. However, this antiquarian reworking of northern pasts operated within a biblical and classical frame of reference, which in effect served to conquer—indeed colonize—northern pasts by assimilating them into southern, European cultural spheres and narratives. Thus, although the North was given a pre-eminent role in Gothicist visions of the past, it was done in colonizers’ terms and by casting northern pasts in a southern mould.

This can also be seen as a form of rendering the unknown North more familiar and ‘civilizing’ the past of the northern borderlands, as well as a means of symbolically homogenizing and unifying the Swedish realm, in addition to contributing to Sweden's Europeanization through the appropriation of the classical tradition. Even when focusing on the northern margins of the realm, antiquarianism was more about the South than the North, and about a national Swedish identity rather than local northern pasts. The idea that runes were first conceived in the North, for instance, only served to highlight the (imagined) Swedish contribution to the great story of history, and Lapland was merely exploited as a symbolic resource for that purpose. The distant, exoticized and poorly known northern fringe was indeed important in this respect, as it afforded projecting fantasies on it and discovering new, unexpected and wondrous things about the past—indeed even the origins of civilization—just as it was thought to be pregnant with material riches and treasures.

Maupertuis’ reflections most clearly echo the colonialist ideology within which the early modern interests in the Vinsavaara stone unfolded. His comparison of the stone to Greek and Roman monuments resonates with the centrality of classical civilizations in the early modern understanding of the past. While Maupertuis accepted the possibility that the grooves on the stone might be the oldest inscription in the world, he rejected the local tradition about the ancient knowledge that the stone contained. In his view, the locals were an unreliable source about such matters because they did not necessarily even know their own age, or who their mothers were. Maupertuis was of the opinion that the local ‘Lapps’ who ‘lived in the forest like wild animals’ would never have experienced anything worth passing on to future generations, nor would they probably have had the knowledge or skills to document anything on the stone. If the inscription were indeed genuine, it would have been made by a civilization that flourished long ago in more favourable climatic conditions, and of which nothing besides the Vinsavaara monument survived (Pekonen Reference Pekonen2005, 26; Pekonen & Vasak Reference Pekonen and Vasak2014, 191–4).

In attributing the inscription to an ancient and vanished civilization, Maupertuis dissociated the Vinsavaara stone from the early modern inhabitants of Lapland, similarly to the way that monumental earthworks in North America were attributed to a race of ‘Mound Builders’ unrelated to indigenous Americans (Sayre Reference Sayre1998). While Maupertuis saw his ‘Lapps’—it is not quite clear if he had Sámi or northern Finns/Swedes in mind—as wretched people who lacked any notable history, he also described them as pure and innocent (cf. Tacitus Reference Hutton, Peterson, Ogilvie, Warmington and Winterbottom1914, 46.3). This kind of ambiguity was, as discussed earlier, not only characteristic of the images of Lapland/Sápmi, but also typical of colonialist perceptions of indigenous people in general (see Naum Reference Naum2016). Maupertuis, of course, was a foreigner, and foreigners tended to perceive northern Fennoscandia quite differently from Swedes. Both saw the region as exotic, but foreign travellers put an emphasis on the marvels of the North and had little interest in northern pasts, whereas the Swedish (authorities) were preoccupied with northern resources on the one hand, and the deep histories of the northerners on the other (Naum Reference Naum2016, 495–6). Maupertuis was also writing at the time when European perceptions of the North were shifting from a threatening barbarian and enchanted land to that of innocence and nostalgia, which perhaps further added to Maupertuis's views of Lapland/Sápmi (Andersson-Burnett Reference Andersson Burnett2010).

Conclusions

This article has provided a reassessment of the Vinsavaara stone, but also sought to recontextualize the ‘monument’ and its interpretations in a new manner. Although technically speaking a natural rock with no physical traces of human manipulation, and the ‘script’ a result of weathering, the Vinsavaara stone has stirred up imagination and more or less curious interpretations from the late seventeenth century up to the present day. This article has discussed several material features of the stone on the one hand, and the cultural-cosmological setting of the various interpretations on the other, both of which facilitated or prompted the notions that the Vinsavaara stone is—at least potentially—a genuine relic from a deep past. The ambiguous character of the stone itself has supported the notion that there might be something special to it—most recently as a hypothetical Sámi sieidi—but the northern land where the Vinsavaara stone is located has also contributed to how it has been signified. That is, Lapland has long been poorly known and exoticized, and as such formed a canvas for all kinds of expectations and cultural projections, a place where both riches and strange things can be discovered. The case of the Vinsavaara stone and how it has been signified offers a prismatic view on how nationalistic, colonialist and classicizing policies and practices have shaped northern Fennoscandia—including the perceptions and ideas of its pasts—since the early modern period.

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by, and is part of, the projects ‘Collecting Sápmi: Early Modern Globalization of Sámi Material Culture and Contemporary Sámi Cultural Heritage’, based at the University of Uppsala, Sweden, and funded by the Swedish Research Council (grant number 421-2013-1917), and ‘Understanding the Cultural Impact and Issues of Lapland Mining: A Long-Term Perspective on Sustainable Mining Policies in the North’, based at the University of Oulu, Finland, and funded by the Academy of Finland (decision number 283119). We wish to express our gratitude to Dr Matti Salo, Pauli Haapakangas MA, Paula Pelttari MA and Tuuli Koponen MA, for their help and assistance with this research and the two CAJ reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript.