Over the past several years, economic inequality has become one of the most discussed topics in social science and social policy. Indeed, no serious discussion of contemporary social and economic life seems complete without a consideration of the growing level of economic inequality that we have seen over the past several decades. In this chapter, I will explore whether, and how, economic inequality – the distribution of income and wealth across social strata – affects the formation and dissolution of families. I write from the perspective of the United States, but I hope my view will be valuable for students of Western Europe and the other overseas English-speaking countries. I will focus on different-sex couples, for whom an historical argument can be assessed. Studies of same-sex couples are underway, and it is not yet clear whether the dynamics are different. I will examine whether economic inequality may be affecting patterns of entry into and exit from cohabitation and marriage, as well as childbearing within or outside marriage. Nevertheless, I will acknowledge that cultural change matters too. Economic conditions are not all powerful. The changes that we have witnessed in family formation would not have happened had the Western world not seen a great shift in attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation over the past half-century.

I have elsewhere referred to these cultural shifts as the deinstitutionalization of marriage (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004). In retrospect, I think that a more accurate, although less elegant, phrase would have been “the deinstitutionalization of intimate unions.” Marriage itself retains much of its distinctive structure and legal protections, even if it has a less clear set of rules for how spouses are to behave than in the past, but it no longer has a monopoly on intimate unions. A majority of partnerships now begin as cohabiting unions. Cohabiting couples cannot rely on shared understandings and legal statutes to guide their interactions. Rather, they must negotiate how they will act in their relationships. They exhibit a wide variation in commitment. In northern Europe, one commonly finds cohabiting couples who have had long-term stable relationships without ever marrying (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2001), but in the United States, most cohabiting unions lead either to break-ups or to marriage within a few years (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2009). An increasing number of American children are now born into them – one in four at the rates in 2015 (Wu Reference Wu2017). In some cases, the parents may not begin to cohabit until after the woman becomes pregnant (Rackin and Gibson-Davis Reference Rackin and Gibson-Davis2012). Children born to cohabiting couples are exposed to a substantially higher risk of parental union dissolution than are children born to married couples – a relationship common across almost all European countries (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017). Childbearing in cohabiting unions is much more common among Americans without university degrees than among university graduates (Wu Reference Wu2017). A clear social-class line now divides American families at the university-degree level, with graduates much more likely to marry before having a child and less likely to end their marriages. Indeed, it almost seems as though the United States has two family formation systems that are differentiated by the presence or absence of a university degree (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2010).

Economic inequality is relevant for explaining these divergent patterns in partnerships and fertility. A long line of research links marriage formation to labor market opportunities for young men (Becker Reference Becker1991; Oppenheimer Reference Oppenheimer1988; Parsons and Bales Reference Parsons and Bales1955). Men have been, and still are, required to earn a steady income; more recently, it has become desirable, but optional, for women to earn one too – at least among nonpoor couples. Therefore I will focus most of my attention to the changes in the labor market that have affected men. Aggregate-level (e.g., cross-national or cross-state) studies have addressed the consequences of inequality for family-related outcomes, such as the percentages married (Loughran Reference Loughran2002) or divorced (Frank, Levine, and Dijk Reference Frank, Levine and Dijk2014), and for teenage pregnancy and birth rates (Gold et al. Reference Gold, Kawachi, Kennedy, Lynch and Connell2001). My coauthors and I have shown that individuals are more likely to marry before childbearing in places where labor market conditions are better than in places where middle-skilled jobs are scarce (Cherlin, Ribar, and Yasutake Reference Cherlin, Ribar and Yasutake2016). However, statistical studies require specialized knowledge to evaluate, and their mathematical models are almost always subject to limitations. Consequently, nonspecialists often have understandable difficulties evaluating the worth of statistical claims that are made. In this chapter, I would like to present a less technical argument for the proposition that rising income inequality has been an important driver of changes in family. Think of it as a prima facie case – a set of facts that establishes the likelihood that an argument is true, even though it does not prove it. The facts, I hope, will establish the plausibility that income inequality has been an important causal factor. It will also suggest that explanations that reject the importance of income inequality and instead argue that cultural change is the sole driver (e.g., Murray Reference Murray2012) are at best incomplete.

The Dimensions of Income Inequality

Income inequality has several dimensions. Two have received close attention in social commentary. First, much has been written about the growing proportion of income and wealth accruing to people in the highest 1% of the distribution (e.g., Piketty and Saez Reference Piketty and Saez2003). Between the late 1970s and the early 2010s, the amount of income amassed by the top 1% from about 10% to about 20% (Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez Reference Atkinson, Piketty and Saez2011). As dramatic as this rise has been, I would argue that it is not the most important dimension of inequality to think about when studying changes in family structure. Rather, what matters more is a second dimension of inequality: The growing earnings gap between the university-educated (by which I mean individuals with a bachelor’s or university degree or higher) and the nonuniversity-educated. This gap has widened since the 1970s (Autor Reference Autor2014). Prior to that time, manufacturing jobs were more plentiful in the United States. The nation had emerged from World War II as the economic power of the world. In 1948, American factories produced 45% of the world’s industrial output, and the nation’s manufacturing exports accounted for a third of the world total (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). The booming economy and a relative shortage of labor (due to the lower birth rates during the Great Depression) created conditions that were favorable to unionization; and labor unions negotiated for higher wages and better fringe benefits (Levy and Temin Reference Levy, Temin, Brown, Eichengreen and Reich2010).

Yet beginning with the oil embargo by the Arab states in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries in 1973, the long postwar boom subsided. The wages of production workers remained stagnant or declined as manufacturing work moved overseas, where wages were much lower, or was automated, lowering the demand for workers. The proportion of workers who were doing what was commonly called blue-collar work – production workers, craftworkers, fabricators, construction workers, and the like – declined. In contrast, demand for high-skilled professional, managerial, and technical workers remained strong – a development that economists refer to as skill-biased technical change (Autor, Katz, and Kearney Reference Autor, Katz and Kearney2008). It produced a growing earnings gap between middle-skilled workers, who tend to have a secondary-school education, and highly skilled workers, who tended to have a university education. Autor (Reference Autor2014) has estimated that in the period from 1979 to 2012, the rising earnings gap between the typical university-educated household and secondary-school-educated household has cost the latter four times as much in lost income as has the growing concentration of income among the top 1%.

The rising earnings gap has increased inequality by hollowing out the middle of the income distribution, producing what some have called the hourglass economy – a metaphor for the pinched middle (Leonard Reference Leonard2011). Industrial jobs have been the easiest to automate or outsource because they require routine production that can be done by computer or robots or that can be carried out in factories situated far from the place at which the goods they produce will be consumed. In contrast, many low-paying service jobs must be done in person (e.g., waiters, gardeners); and high-paying managerial and technical jobs have remained uncomputerized and performed in the United States. as well. The polarization of low-paying and high-paying jobs, with fewer mid-level jobs in between, creates a higher level of income inequality.

Income Inequality and Family Formation

How then might rising income inequality be associated with changes in family formation? My argument is that the presence of high levels of income inequality is a signal that a weakness exists in the middle of the labor market. That weakness creates the conditions that change family formation. To be sure, income inequality may not inherently be a direct causal force for family change. Perhaps other forms of income inequality in other places at other times might not be as strongly associated with the hollowing out of the middle of the labor market and therefore might have little effect. However, the inequality that we have seen in the United States is connected to the labor market, in that it is harder for a person with a moderate amount of skill – say, a secondary-school diploma and perhaps a few university courses – to get a decent-paying job. In turn, the difficulty of finding middle-skilled jobs depresses rates of marriage and of marital fertility.

The prima facie case for the causal importance of income inequality rests on two basic trends. The first trend is the aforementioned growth since about 1980 of the earnings differential between the university-educated and the less-educated (Autor Reference Autor2014). As I have noted, this gap reflects the relative decline in job opportunities in the middle of the labor market – the kinds of jobs that people without university degrees are qualified for. In addition, among individuals without a university education, the disruption in the middle of the labor market has been sharper for men than for women. Much of the automation and offshoring has occurred among manual occupations that had been seen as men’s work due to their physical, often repetitive, nature at a factory or a construction site. In the American ideal of the working-class family that was socially constructed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, men were supposed to do jobs that required hard physical labor and to bring home a paycheck for the needs of their wives and children. Sociologist Michèle Lamont refers to this conception of the male role as the “disciplined self” (Lamont Reference Lamont2000) and claims that it has been common among White working-class men in the United States. (Lamont found that the self-sufficient breadwinner image was less common among Blacks.) It is this type of manly work that has been subject to shortages and to wage stagnation. Initially, working-class husbands took pride in keeping their wives out of the labor force, but in the postwar period, women moved into paid employment in clerical and service work – the so-called pink-collar jobs that came to be seen as women’s work. Jobs in this sector of the economy have not been hit as hard by the offshoring and automation of production. Consequently, men and women’s earnings have moved in different directions. Between 1979 and 2007, men’s hourly earnings decreased for all those without university degrees. For women, earnings fell only for those without secondary-school diplomas; all others experienced increases. Alone among male workers, the university graduates experienced an increase; and for women, the largest increases were for university graduates (Autor Reference Autor2010).

The second basic trend consists of the divergent paths that family structure has taken during the same period, according to the educational levels of the adults involved. In the 1950s, marriage was ubiquitous. At all educational levels, almost everyone married, and almost all children were born within marriage (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992). The central position of marriage in family life began to erode in the 1960s and 1970s. Crucially for my argument, the trends in marriage and childbearing were initially moving in the same direction for adults at all educational levels: Marriage was being postponed, cohabitation was increasing, and divorce rates were rising (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992). However, since about 1980, the family lives of those with a university degree, whom we may call the highly educated, and those with less education have diverged (McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004). Family life among the highly educated remains focused on marriage as the context for raising children, and although the highly-educated marry at later ages, they ultimately have higher lifetime marriage rates than do those with less education (Aughinbaugh, Robles, and Sun Reference Aughinbaugh, Robles and Sun2013). In addition, the divorce rate for highly educated couples has declined sharply since its peak around 1980 (Stevenson and Wolfers Reference Stevenson and Wolfers2007). Meanwhile, the percentage of births outside marriage among the highly educated has remained low. In contrast, the family lives of people with a secondary-school diploma but not a university degree, whom we may call the moderately educated, have moved away from stable marriage. This group has experienced a surge of births within cohabiting unions. Unlike the typical cohabiting unions in some European countries, these unions tend to be brittle and to lead to disruptions at a high rate (Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2015). Among moderately educated married couples (those with secondary-school diplomas), there has not been as much decline in divorce as among the highly educated (S. P. Martin Reference Martin2006). Finally, people without secondary-school degrees, whom we may call the least-educated, have continued to have a high proportion of births outside marriage, although there has been less change in their family patterns since 1980.

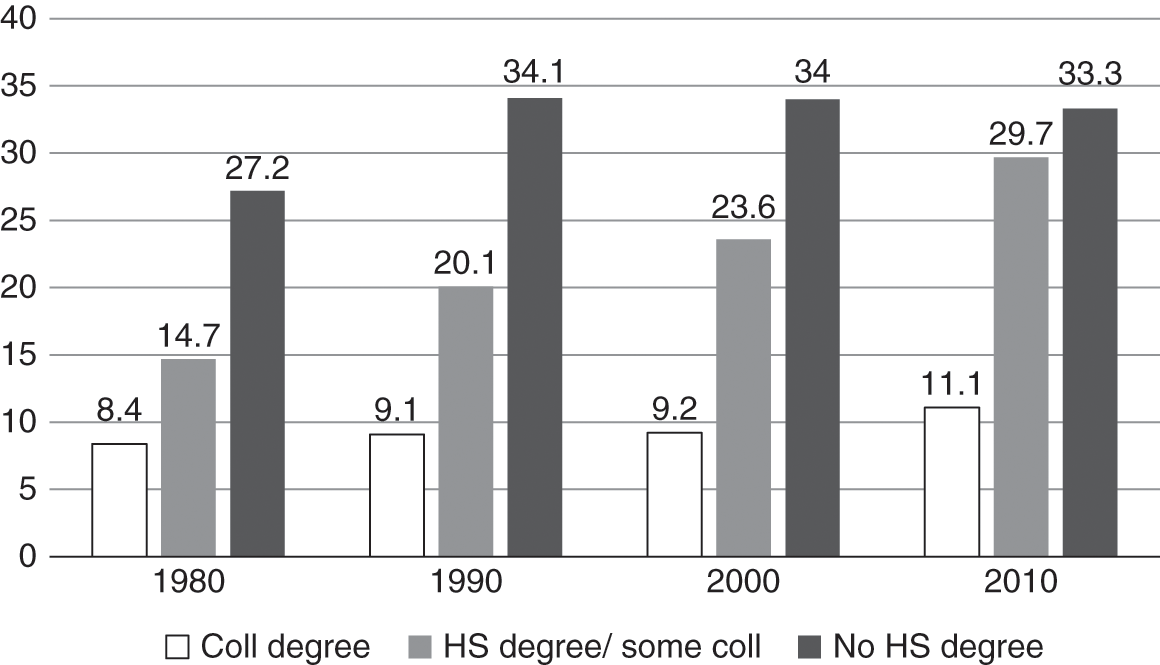

Consequently, the greatest change in children’s living arrangements since 1980 has occurred among the moderately educated, among whom the proportion of children living with single mothers and cohabiting mothers has increased dramatically. Figure 3.1 shows changes in children’s living arrangements for the thirty-year period from 1980 to 2010. Consider the white-colored bars, which show the percentage of children with highly educated mothers who are living in a single-parent or cohabiting-parent family. It hardly changed during the thirty-year period – rising from 8% to 11%. In other words, there was little or no movement away from marriage-based families for the raising of children. Now look at the dark-gray bars, which show children living with least-educated mothers. They were the most likely to live in single-parent or cohabiting-parent families in all years but after increasing from 1980 to 1990, the rate has held steady.

Figure 3.1 Percentage of children living with single and cohabiting mothers, by mother’s education, 1980–2010.

It is the light-gray bars, which show children living with moderately educated mothers, that portray the greatest changes in family structure. Here we see the substantial growth of the proportion of children living in single-parent or cohabiting-parent families – from 15% to 30%. Thus, it is among the moderately educated, that we see both the greatest change toward nonmarital, unstable living arrangements for having and rearing children and the greatest erosion of labor market opportunities – and we see both trends commencing at roughly the same point in time. It is among the highly educated that we see the opposite pairing of trends: Continued high levels of children living in more stable marriages centered on marriage coincided with a rise in the earnings premium for university graduates. This is the prima facie case for the proposition that rising income inequality has been an important indicator of changes in family formation – a marker for the deterioration of the middle of the labor market, especially for men, and an improvement in the labor market for the university-educated. Those who experienced a deteriorating job market trended toward less stable family environments. Those who experienced an improvement in the job market trended toward stable marriage-based family environments.

Many of the highly educated are living an advantaged family life, with two earners providing an ample household income. It is the flipside of the family troubles experienced by the moderately educated. In fact, a number of European and American researchers are claiming that the relatively stable unions of the highly educated are based on a new marital bargain in which the partners share the tasks of paid work, housework, and child-rearing more equally than in the past (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen2009, Reference Esping-Andersen2016; Esping‐Andersen and Billari Reference Esping–Andersen and Billari2015; Goldscheider, Bernhardt, and Lappegård Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015). For these observers, the key driver has been the change in women’s roles and the normative shift it has caused. In the mid-twentieth century, marriage and family life was in a stable equilibrium based on a specialization model in which the wife did the housework and child care and the husband did the waged work. When wives began to move into the labor force, they also began to ask their husbands to do more in the home. The result, it is said, was several decades of disruption and dissension as husbands resisted taking on more of what had been seen as wives’ work and as welfare states were slow to support women wage workers through programs such as child-care assistance. However, these scholars argue that a new egalitarian equilibrium is emerging that is based on the sharing of both market and housework by the partners, who may now be either married or cohabiting, and who rely on expanded state support for two-earner families. Social norms, according to this view, have evolved from a breadwinner/homemaker equilibrium in the 1950s to an egalitarian equilibrium that is emerging now.

However, an important limitation of this argument is that the egalitarian bargain rests on the availability of good labor market opportunities for men and generous family-friendly social welfare benefits for couples, such as child-care assistance and family leave. Although the husband is no longer required to be the sole earner of the family, there is still a widespread norm that a man must have the potential to be a steady earner in order to be considered as a good long-term partner (Killewald Reference Killewald2016). Among the moderately educated and least-educated, it is increasingly difficult for men to demonstrate sufficient potential. Consequently, the emergence of a gender-egalitarian equilibrium of committed, domestic work-sharing couples in long-term relationships is likely to be more common in the privileged, university-educated sectors of Western nations than in the less-advantaged, lower educated sectors.

The Influence of Cultural Change

The main counterargument to the prima facie explanation I have presented is that changes in social norms have driven both the decline in earnings among the nonuniversity graduates and the changes in family structure that occurred over the same time span. To be sure, culture is part of the story. During the Great Depression, job opportunities were scarce and yet there was no increase in the percentage of children who were born outside marriage. The reason is that having an “illegitimate” child, as it was called at the time, was socially unacceptable and stigmatizing. Today nonmarital births are much more acceptable than in the past. Without this greater cultural acceptance of alternatives to marriage, we would not have seen the rise in births to cohabiting couples in the United States. Moreover, the weakening of marriage began in the early 1960s, well before the dramatic rise in inequality occurred (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992).

In fact, marriage is much less central to Americans’ sense of their adult identity today than it was in the past. In the 2002 wave of the General Social Survey – a biennial survey of American adults that is conducted by the research organization NORC at the University of Chicago – respondents were asked which of several milestones a person had to accomplish in order to be an adult. More than nine out of ten selected markers such as being economically independent, having finished one’s education, and not living in one’s parental home, but only about half agreed that one had to be married to be an adult (Furstenberg et al. Reference Furstenberg, Kennedy, McLoyd, Rumbaut and Settersten2004). In the mid-twentieth century, the first step a young person took into adulthood was to get married. The average age at marriage in the 1950s was about 20 for women and 22 for men (US Census Bureau 2016). Only then did you leave home: 90%–95% of all young people married. Today, marriage’s place in the life course, if it occurs at all, is often at the end of the transition to adulthood (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004). Other paths to adulthood, including having children prior to marrying, cohabiting, and perhaps never marrying, are common and largely acceptable.

A further cultural counterargument is that an erosion of social norms supporting hard work has caused the declining work rates of men, at least in the United States, and by extension, family instability (Eberstadt Reference Eberstadt2016; Murray Reference Murray2012). Although we have seen changes in men’s and women’s work and family roles, one norm has held constant: Men must be able to provide a steady income in order to be considered good candidates for marriage. Killewald (Reference Killewald2016) found that men who are not employed full-time have an elevated risk of divorce, but that low earnings were not necessarily a risk factor as long as the men worked steadily. Other studies suggest that while a woman might choose to cohabit with a man whose income potential is in doubt, she is unlikely to marry him – and he may agree that he is not ready. In focus groups conducted with cohabiting young adults in Ohio, several couples told the researchers that everything was in place for a wedding except for the finances, and that until they were confident of their finances, they would not marry (Smock, Manning, and Porter Reference Smock, Manning and Porter2005).

It is alarming to some observers, then, that the percentage of prime-age men who are working or looking for work has declined, particularly among men without university degrees. Eberstadt (Reference Eberstadt2016) reported that the percentage of 25–54-year-old men who were employed dropped from 94% in 1948 to 84% in 2015. He cites a number of factors, including the employment problems faced by the growing number of men who have returned to the general population after serving prison sentences, but he suggests that a decreasing motivation to work among certain groups of men may be part of the story. In contrast, university-educated men are working almost as hard as in the past (Jacobs and Gerson 2005). One might think, then, that university graduates prefer to work longer hours more than do less educated men.; however, that is not true.

In fact, the General Social Survey shows that there has been a decline in the desire to work long hours among both secondary-school-educated men and university-educated men. In several of the survey’s biennial waves, respondents were handed a card showing five characteristics of a job and asked to rank them in importance. One characteristic was “Working hours are short, lots of free time.” In the 1973–1984 period, the proportion of men aged 25–44 who rated it as most or second-most important was 13%; in the combined 2006 and 2012 samples, it rose to 28% (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). It seems, then, the percentage of men who highly valued short working hours and lots of free time has increased. However, the increase was just as sharp for university graduates as it was for those with a secondary-school diploma but not a university degree. (There was no increase among men without secondary-school diplomas.) So both moderately educated and highly educated men seem to value working short hours more than they used to. Yet only the moderately educated men are actually working less than they used to. On the contrary, Americans working in the professional, technical, and managerial sectors of the labor force tend to work longer hours than their European counterparts (Jacobs and Gerson 2005). The survey results therefore raise this question: If both highly educated men and moderately educated men had a growing preference for shorter hours and more free time, why was only the latter group actually working shorter hours than in the past?

The answer, I would argue, is that employment opportunities and earnings levels for the university-educated men were improving so much that some of these men decided to work longer hours than they preferred: The attraction of the jobs that were available to them – notably higher wages and salaries – more than balanced their attraction to free time. Among moderately educated men in contrast, employment opportunities were not attractive enough to override their growing preference for free time. In other words, whether a man is working depends on both his preferences for work and the opportunities available to him. The decline in men’s labor force participation is rooted in a cultural shift as well as a change in the labor market. Both cultural and labor market factors are necessary to explain the decline.

More generally, this example suggests how intertwined economics and culture are in producing the trends we have seen in family life. Economic sociologists have long argued that economic action is embedded in social institutions (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1985): People make decisions about employment in a cultural milieu. Currently, that milieu may be more favorable toward other activities and leisure than in the past. Some observers might judge that milieu negatively and decry the choices working-age men may make, but cultural forces can be overridden by the opportunity for higher paying, stable work or they can be reinforced through job opportunities that are insecure and lower paying. Cultural forces do not alone determine how young adults will relate to family and work, and nor, it must be said, do economic forces.

One other cultural phenomenon may be contributing to the class differences, not by its transformation but by its stubborn persistence: Ideas about masculinity (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). As I noted earlier, working-class men have taken pride in hard physical labor. Meanwhile jobs that involved caring for and serving others came to be associated with women. These caring-work jobs typically pay less than industrial jobs, which may explain some of the reluctance of men to take them, but they also seem to be devalued in status, at least among men, precisely because they are seen as unmanly jobs (England Reference England2005). As a 53-year-old man who had lost several jobs to automation and to factories that moved to other cities, told a reporter for the New York Times, he never considered work in the health sector of the labor market: “I ain’t gonna be a nurse; I don’t have the tolerance for people,” he said. “I don’t want it to sound bad, but I’ve always seen a woman in the position of a nurse or some kind of health care worker. I see it as more of a woman’s touch” (Miller Reference Miller2017). What we might call conventional masculinity – and what the literature sometimes calls “hegemonic masculinity” (Connell Reference Connell1995) – still prescribes that some jobs are men’s jobs and others are for women. The problem is that men’s jobs have been disproportionately affected by the globalization and automation of production. In the meantime, service jobs have opened up, as in the health sector, but men have resisted taking them. Working-class men’s resistance to doing jobs that are not considered manly enough contributes to the difficulties they face in the labor market.

Discussion

The social-class differences in family formation that are apparent today are not unprecedented. Rather, we are seeing, in a sense, a return to the historical complexity of family life (Therborn Reference Therborn2004). That complexity was apparent throughout the early decades of industrialization during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when there was a great growth of factory jobs. During this period, traditional-skilled jobs in the middle of the labor market, such as those performed by independent craftsmen, yeomen, and apprentices in small shops, were undercut by factory production. Independent shops either collapsed or turn into larger factories. Inequality increased, and as is the case today, the middle of the labor market was hollowed out. Sharp social-class differences in marriage rates were visible; professional, technical, and managerial workers were more likely to marry than were workers with less remunerative jobs (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). The prosperous period of stability just after World War II, when almost everyone married, fertility rates were high, and divorce rates were unusually stable (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992), was the most unusual time in family life since industrialization and should not be taken as an anchor point.

Nevertheless, the complexity of family life we see today is different from the complexity of the past. The high rates of cohabitation and of childbearing outside marriage that are now prevalent were rare during the disruptions of early industrialization. Nor, as I noted, were they present during the disruption of the Great Depression. The culture of family life was different; alternatives to marriage such as cohabitation and single-parent families (other than those due to widowhood) were unacceptable to most people. So if a young adult was not married, he or she probably lived in the parental home or boarded in another family’s home and remained childless. The growth in the number of people who were living alone is largely a post-World War II phenomenon, as the housing stock increased and wages and salaries (and therefore the ability to pay rent) rose (Kobrin Reference Kobrin1976; Ruggles Reference Ruggles1988). The lives that unmarried young adults in the United States led in the past are more similar to family life today in countries such as Italy, where it is common for twenties to live at home, remain childless, and marry in their late twenties and early thirties.

One must also include the growth of a more individualistic, self-development oriented culture in the story of changes in family formation today. This cultural development may be connected to a larger shift among the population of the wealthy countries to what are called post-materialist values (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997). As societies have become wealthier and have solved the problem of providing basic needs, it is said individuals have come to value self-expression – the development of one’s personality – over survivalist values such as providing food, shelter, and basic financial support. One aspect of self-expression is the examination of whether one’s intimate partnership continues to meet one’s needs. If not, the self-expressive individual will consider ending that partnership and finding a new one that better fits her or his continually developing self. Thus, self-expression is associated with higher rates of union dissolution and re-formation. Post-materialist values also include a decline in traditional religious beliefs; in the West that decline is consistent with a rise in nonmarital partnerships and childbearing outside marriage. Overall, a rise in post-materialist values is consistent with what demographers have called the second demographic transition (van de Kaa Reference Van de Kaa1987; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn Reference Lesthaeghe and Surkyn1988): The period since the 1970s during which cohabitation, nonmarital births, and low fertility have become common in most Western countries. Moreover, during this period, there has been a decline in civic engagement – social ties, attendance at religious services, and participation in local associations – that has been more pronounced among those without university educations (Putnam Reference Putnam2015).

Note, however, that second demographic transition theory does not explain the continued strength of marriage and the decline in divorce rates that have occurred among highly educated Americans in this period. It provides no explanation for a seeming transition back toward a family form characterized by relatively stable marriage, albeit preceded by cohabitation. Highly educated young adults were previously thought to constitute the nontraditional vanguard, providing new models of family life that diffused down the educational ladder. That is not, however, what we have seen; rather, the patterns in the United States suggest a neo-traditional highly educated class and a growth of nontraditional behavior among those with less education. At least in the United States, then, second demographic transition theory cannot provide us with an explanation for the growing divide in family life.

That divide suggests a role for the momentous changes in the economy that have differentially affected the highly educated and the less educated. Nevertheless, one must be careful in attributing social change solely to economic inequality. It has become the go-to explanation for a wide variety of social phenomena. One frequently cited book claims that inequality has caused anxiety and chronic stress that has led to a long list of consequences that include poorer physical health, higher mortality, greater obesity, lower educational attainment, higher teenage birth rates, greater exposure among children to conflict, higher rates of imprisonment, more drug use, less social trust, and less social mobility (Wilkinson and Pickett Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2009). All of this is deduced solely from macro-level correlations at the national or state level. It seems unlikely that any social phenomenon could have effects this broad, and in any case, macro-level correlations do not prove the case. The claims in the literature (as well as in this chapter) must therefore be carefully scrutinized and subject to further research.

This chapter also presents a very US-centric perspective that may be less applicable in Europe. The American social welfare system is well known to be among the least generous in the Western world – it is the archetype of the “liberal” (free-market oriented) welfare state in the classic formulation of Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) – and compared to other nations, it provides a larger proportion of its benefits through programs that are contingent on work effort (Garfinkel, Rainwater, and Smeeding Reference Garfinkel, Rainwater and Smeeding2010). Therefore, it does less to support low-income families that do not have steady wage earners than do the welfare systems in other countries. It also provides less support for working parents, in terms of paid family leave or child-care assistance. This lack of support may be one reason why rates of union instability and childbearing among single parents are high in the United States from an international perspective (see Chapter 1). Moreover, the idea that a couple should not marry until they are confident that they will have an adequate steady income (Gibson-Davis, Edin, and McLanahan Reference Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan2005) seems to be stronger in the United States than elsewhere. Perelli-Harris (Reference Perelli-Harris2014) and her colleagues convened focus groups in nine settings in Europe to discuss cohabitation and marriage. They found that the rise of education has not devalued the cultural meaning of marriage; however, they did not hear much discussion of economic uncertainty and its relationship to whether a cohabiting couple should marry.

Nevertheless, the prima facie case that inequality – and more specifically the diverging labor market opportunities for the highly educated and the moderately educated – has driven family formation and dissolution seems strong for the United States. It is not the complete explanation for the great changes in these behaviors that have occurred in the past half-century or so, but it does not need to be. To be sure, had bearing children outside marriage not become acceptable, had cohabitation not become the predominant way that young adults enter into a first union, had survival values persisted over self-expressive values, we would not have seen the same retreat from marriage and marital childbearing; however, had employment opportunities for secondary-school-educated men not deteriorated and had corporations not been able to use the mobility of capital to undermine unionized factories, we would probably not have seen the same retreat either. Culture alone cannot explain the increasingly divergent paths by which the university-educated and the nonuniversity-educated are forming and maintaining families. It seems highly likely that one must take into account the economic changes that have occurred in the increasingly unequal American society.