Introduction

Metal mining at Garpenberg, Hedemora, Dalarna (Dalecarlia), Sweden, has been described in annals since the fourteenth Century, however recent studies of Holocene lake-sediment records in the area indicate that small-scale extraction of copper occurred earlier, in the pre-Roman iron age, from ca. 375 B.C. (Bindler et al., Reference Bindler, Karlsson, Rydberg, Karlsson, Nilsson, Biester and Segerström2017). Mining is still active; the current business has been operated since 1957 by Boliden AB, which presently produces 3 Mt of ore per year. The grades are 0.5 g/t Au, 70–160 g/t Ag, 0.1% Cu, 2% Pb and 3–4% Zn (Bolin et al., Reference Bolin, Brodin and Lampinen2003; Tiu et al., Reference Tiu, Jansson, Wanhainen, Ghorbani and Lilja2021).

The sample containing the new mineral presented here was collected in situ at the 900 m level of the Garpenberg Norra mine (60°20′N, 16°13.5′E), where various exotic skarn mineral assemblages have been noted to exist (Eriksson and Kalinowski, Reference Eriksson and Kalinowski2001; Holtstam et al., Reference Holtstam, Gatedal, Söderberg and Norrestam2001; Holtstam, Reference Holtstam2002; Kolitsch and Holtstam, Reference Kolitsch and Holtstam2002; Nysten, Reference Nysten2003). Garpenbergite was first spotted by one of the authors (K.G.) in a polished section. Preliminary chemical data suggested a close relationship to manganostibite, ideally Mn7AsSbO12, a rare mineral first described by Igelström (Reference Igelström1884) from the Nordmark ore field, Filipstad, Värmland, Sweden. A subsequent Raman study, however, indicated a distinct new species (cf. Holtstam, Reference Holtstam2021).

The name of the mineral is for the place of discovery, Garpenberg. In the Middle Ages, ‘garp’ was the colloquial word in Swedish for a German person. The term here refers to the fact that the Swedish Crown recruited German miners at the time in order to increase know-how and develop regulations in the kingdom's growing mining industry (Carlberg, Reference Carlberg and Beckmann1879).

The new mineral species and its name (symbol Grp) have been approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA2020-099, Holtstam et al., Reference Holtstam, Bindi, Förster, Karlsson and Gatedal2021). The holotype material is deposited in the type mineral collection of the Department of Geosciences, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-10405 Stockholm, Sweden, under collection number GEO-NRM #20010351 (specimen and polished section) and #20200040 (polished section).

Occurrence

Garpenberg is situated in the northern part of the Palaeoproterozoic Bergslagen ore region in central Sweden, where numerous stratabound sulfide and (Fe±Mn) oxide deposits are hosted by 1.9–1.8 Ga felsic volcanic rocks and interlayered limestones, with enveloping siliciclastic sedimentary rocks and intruding Svecokarelian plutons (Stephens and Jansson, Reference Stephens, Jansson, Stephens and Bergman Weihed2020). The Garpenberg polymetallic Zn–Pb–Ag–(Cu–Au) sulfide deposit stretches about seven km in a SW–NE direction, and comprises several ore bodies, mainly confined to a marble horizon. Significant mineralisation also occurs in adjacent metavolcanic rocks. At a stratigraphically lower level, several magnetite skarn ores are present. The rock units have experienced pervasive hydrothermal alteration proximal to the ore bodies (Vivallo Reference Vivallo1985; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Bull, Ripa and Jonsson2003), metamorphism and polyphase deformation. Most or all of the Fe oxide and complex sulfide ores in the Garpenberg area formed within the time span 1895–1890 Ma during a syn-volcanic event (Jansson and Allen, Reference Jansson and Allen2011). Peak metamorphic conditions for the deposit are estimated at T ≥ 550°C and P < 0.35 GPa imposed around 1.85 Ga (Vivallo Reference Vivallo1985).

The marbles at Garpenberg host enclaves of sporadic low-S, Mn–Zn–Pb–Ba–Sb–As mineralisation, reminiscent of both Långban (Holtstam and Langhof, Reference Holtstam and Langhof1999; Holtstam and Mansfeld, Reference Holtstam and Mansfeld2001) and Franklin–Sterling Hill (Dunn, Reference Dunn1995; Peck et al., Reference Peck, Volkert, Mansur and Doverspike2009) types of deposits. The genetic relation to the main sulfide ores and skarns at Garpenberg remains unclear.

The size of the sample containing the new mineral is small, ca. 2 cm × 1.5 cm × 1 cm. Garpenbergite occurs in a filled fracture together with mainly carlfrancisite (Fig. 1). Minor stibarsen and paradocrasite appear in fractures of garpenbergite. Filipstadite has been observed in a few cases, as tiny overgrowths on garpenbergite. The rock matrix consists of granular jacobsite, alleghanyite, kutnohorite and dolomite. Following a brittle-deformation event, garpenbergite probably crystallised from a locally mobilised, As–Sb-rich fluid. Redox conditions were apparently varying, as evidenced by the presence of arsenate, arsenite and arsenide mineral species in the same fissure mineralisation. The mineral-forming episode is probably coeval with the transition from ductile to brittle deformation that occurred in the area at ~1.8–1.7 Ga (Stephens and Jansson, Reference Stephens, Jansson, Stephens and Bergman Weihed2020).

Fig. 1. Back-scattered electron scanning electron microscopy image of a polished section of the garpenbergite (Grp) type specimen, with carlfrancisite (Cfc), jacobsite (Jcb), alleghanyite (Alh), dolomite (Dol) and kutnohorite (Kut). The arrow points to one area (white) containing a fine intergrowth of stibarsen and paradocrasite. Sample GEO-NRM #20200040.

Physical and optical properties

The new mineral occurs as heavily fractured, short-prismatic (along [010]) and mostly subhedral crystals up to 1.5 mm in length. The macroscopic colour is blackish to greyish brown, the streak is light brown. Garpenbergite has a sub-adamantine to greasy lustre and is semi-opaque (translucent in thin splinters). The hardness is ~5 on the Mohs scale. The micro-indentation hardness (VHN100), obtained by means of a Shimadzu type-M tester, is 650 (6.37 GPa) based on ten measurements, giving a total range of 580–694. The shape of indentations are straight to slightly concave, with simple shell fractures (Jambor and Vaughan, Reference Jambor and Vaughan1990). Garpenbergite is brittle, with an uneven to subconchoidal fracture. Cleavage is distinct on {010}.

The density was not measured, because of current prohibition of heavy liquids; a calculated value of 4.47(1) g⋅cm−3 was obtained based on the empirical formula and unit-cell volume from single-crystal diffraction data (see below). Garpenbergite is non-magnetic with respect to a neodymium hand magnet, and soluble in 30% HCl (aq) at room temperature. No fluorescence was detected under ultra-violet light.

The optical character in transmitted light could not be determined owing to strong absorption and high refraction of the crystals. The overall refractive index (n) is calculated to 1.847, using Gladstone-Dale constants listed by Mandarino (Reference Mandarino1981). In reflected polarised light, garpenbergite is grey, with no perceptible bireflectance or pleochroism. It is weakly to moderately anisotropic under crossed polars. Reflectance spectra were measured in air with an AVASPEC-ULS2048×16 spectrometer connected to a Zeiss Axiotron UV-microscope (10×/0.20 Ultrafluar objective), using a tungsten filament lamp (100 W) and a dichroic HNPB polaroid filter. Silicon carbide (Zeiss no. 846) was used as standard, and the annular measurement area was ~0.1 mm in diameter on the sample surface. Results from the visible spectrum range (average of 100 scans, 100 ms integration time) are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Reflectance values (in %; wavelengths recommended by the Commission on Ore Mineralogy in bold).

In comparison with the related manganostibite, garpenbergite is slightly more translucent, and has a lower overall reflectance.

Raman spectroscopy

A micro-Raman spectrum of garpenbergite (Fig. 2) was obtained from a crystal in the polished section on a LabRAM HR 800 spectrometer, using a 514 nm Ar-ion laser source at < 1 mW power, a Peltier-cooled (–70°C) 1024 × 256 pixel CCD detector, a Olympus M Plan N 100×/0.9 NA objective and laser spot of ca. 3 μm. A 600 grooves/cm grating was used, and the spectral resolution is ~1 cm–1. Peak positions were corrected against the Raman band at 789 cm–1 of a silicon carbide crystal. Instrument control and data acquisition (range 100–4000 cm–1, 10 s exposure time in 20 cycles) were made with the LabSpec 5 software. Laser-induced degradation of the sample was not observed. A single crystal of manganostibite (from Igelström's type specimen, GEO-NRM #18840177) was measured with the same settings for a comparison (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Raman spectra of garpenbergite and manganostibite, obtained with a 514-nm laser.

Observable bands are at 3647, 3622, 1300, 1020, 818, 791 (shoulder), 695, 659, 620 (shoulder), 580, 541, 512, 482, 464, 339, 259 and 233 cm−1. The two distinct Raman bands above 3600 cm−1 are related to OH-stretching vibration modes. The strongest peak at 818 cm−1 (with shoulder at 791 cm−1) corresponds to stretching vibrations of the [AsO4]3− groups (Myneni et al., Reference Myneni, Traina, Waychunas and Logan1998). Bands in the region 695–620 cm−1 are attributable to the symmetric and antisymmetric stretching modes of SbO6 octahedra (cf. Guillén-Bonilla et al., Reference Guillén-Bonilla, Rodríguez-Betancourtt, Flores-Martínez, Blanco-Alonso, Reyes-Gómez, Gildo-Ortiz and Guillén-Bonilla2014), whereas peaks at lower frequencies down to ~450 cm−1 probably arises from the Mn(Mg)–O stretching in tetrahedra and octahedra. Specifically, bands around 530 cm−1 could be attributed to octahedrally coordinated Mn2+ (Bernardini et al., Reference Bernardini, Bellatreccia, Della Ventura and Sodo2021). In the spectrum of manganostibite, corresponding bands occur at similar positions (within 10–20 cm−1), with a clear exception for the OH vibration modes, which are absent.

Chemical composition

Preliminary energy-dispersion (EDS) X-ray measurements on a polished sample section showed Mn, Mg, Sb, As, Zn and O to be present in garpenbergite. The chemical composition was ultimately determined using a JEOL JXA 8230 electron microprobe operating in wavelength dispersive spectroscopy mode at 15 kV and 20 nA, with a defocused beam size of 10 μm (to minimise diffusion of elements mobile under the electron beam). Measurement time on peaks and background was 20 and 10 s, respectively. Reference materials and measured lines were: rhodonite (SiKα), orthoclase (AlKα), Fe2O3 (FeKα), MnTiO3 (MnKα), diopside (MgKα and CaKα), adamite (AsLα and ZnKα), InSb (SbLα), fluorite (FKα) and tugtupite (ClKα). The number of spot analyses was 49. The H2O content was not determined directly, because of scarcity of material. No CO2 was indicated by crystal structure refinements or spectroscopic data. The following elements were sought but found to be below detection: Na, Ca, Al, P, V and F. The results of the analyses are given in Table 2. Associated carlfrancisite was also analysed (10 spots) at the same analytical conditions, and gave: SiO2 8.41, Al2O3 0.12, Fe2O3 0.77, MnO 51.84, MgO 10.87, CaO 0.03, As2O5 18.23, Sb2O5 0.06, ZnO 0.42, F 0.11, H2Ocalc 8.31, total 99.17 (all in wt.%).

Table 2. Chemical composition of garpenbergite (in wt.% oxide).

*Inferred from crystal structure, (OH + Cl) = 2 apfu.

The empirical formula of garpenbergite, calculated on the basis of eight cations and assuming – as inferred from crystal-structural features – As and Sb as pentavalent cations, and with the Mn2+/Mn3+ ratio adjusted to obtain overall electro-neutrality, is (Mn2+3.97Mg1.48Mn3+0.26Zn0.29)Σ6.00(As0.89Fe3+0.04Mn3+0.06Si0.01)Σ1.00(Sb0.98Fe0.02)Σ1.00O10[(OH)1.99Cl0.01]Σ2.00. The ideal formula becomes Mn2+6□As5+Sb5+O10(OH)2, which corresponds to (in wt.%) MnO 59.10, Sb2O5 22.44, As2O5 15.96, H2O 2.50, total 100.00.

The empirical formula for associated carlfrancisite, based on 96 anions with (OH, F) = 42 atoms per formula unit (apfu) and As3+ = 2 apfu, is Mn32+(Mn2+30.42Mg12.33Zn0.24Ca0.02)Σ43.01(As3+O3)2(As5+O4)4[(Si0.80As5+0.11Fe3+0.06Sb0.02Al0.02)Σ1.01O4]8(OH0.98F0.02)42.

X-ray diffraction data and crystal-structure refinement

Powder X-ray diffraction data (Table 3) were obtained with a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with Photon III CCD detector and using copper radiation (CuKα, λ = 1.54138 Å), with 600 s of exposure; the detector-to-sample distance was 7 cm. The program Apex3 (Bruker AXS Inc., 2016) was used to convert the observed diffraction rings to a conventional powder diffraction pattern. A least-squares refinement of the orthorhombic unit cell gave the following values: a = 8.6919(10) Å, b = 18.927(3) Å, c = 6.1110(6) Å and V = 1005.3(1) Å3 for Z = 4.

Table 3. Powder X-ray diffraction data (d in Å) for garpenbergite*.

* The calculated diffraction pattern was obtained with the atom coordinates reported in Table 5 (only reflections with I rel ≥ 4 are listed; strongest experimental values in bold).

A single-crystal X-ray diffraction study was performed on a 55 μm × 45 μm × 40 μm crystal fragment (counterpart of the piece used to make polished section for electron probe analysis) using a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with Photon III CCD detector, with graphite-monochromatised MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å), with 20 s exposure time per frame; the detector-to-sample distance was 60 mm (summarised in Table 4). The small fragment was mounted on a 5 μm diameter carbon fibre, which was, in turn, attached to a glass rod. The diffraction intensity data were integrated and corrected for standard Lorentz polarisation factors with the software package APEX3 (Bruker AXS Inc., 2016). A total of 1317 unique reflections was collected up to 2θ = 73.40°. The program SHELXL (Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2015) was used for the refinement of the structure. The structure solution was initiated from manganostibite structure data (Moore, Reference Moore1970), and the structure solution was undertaken in the space group Ibmm.

Table 4. Crystal data and experimental conditions for the single-crystal XRD study.

*Weighting scheme: w = q / [σ2(F o2) + (a*P)2 + b*P + d + e*sin(θ) ] where P = [ f * Maximum of (0 or F o2) + (1–f) * F c2 ]

Though it has a nearly identical unit-cell geometry and structural topology with manganostibite (Moore, Reference Moore1970), it was immediately realised that the octahedral position at the origin of the cell in manganostibite is empty in garpenbergite (see below), thus giving an overall content of M cations = 6, and not 7 as in manganostibite (cf. Table 5).

Table 5. Atoms, Wyckoff positions (Wyck.), mean electron numbers, inferred site populations, fractional coordinates of atoms, and isotropic displacement parameters in the structure of garpenbergite.

The site occupation factor (s.o.f.) at the cation sites was allowed to vary (Mn vs. Mg for the M sites and Sb vs. As for the other metal sites) using scattering curves for neutral atoms taken from the International Tables for Crystallography (Wilson, Reference Wilson1992). The refinement of the site-occupancies gave the scattering values and the possible site populations reported in Table 6 (unconstrained refinement). At this point, taking into account the observed bond distances (Table 7), the s.o.f. occurring at the M and Sb/As sites, and the electron microprobe analysis, the following site populations were proposed: Sb = Sb1.00; As = As0.89Fe0.06Mn0.04Si0.01; M1 = Mn0.71Mg0.22Zn0.07; M3 = Mn0.70Mg0.30; and M4 = Mn0.71Mg0.22Zn0.07 (Table 6). These proportions were then fixed in subsequent refinement cycles (see Table 6 – constrained refinement). The bond-valence sums (Table 5) indicate O1 as a likely hydroxyl ion in the structure. However, the individual H atoms could not be located in the difference-Fourier maps.

Table 6. Site-scattering values and site occupancies of garpenbergite.

SCXRD – single-crystal X-ray diffraction; EPMA – electron microprobe analysis.

Table 7. Selected bond distances (Å) in the crystal structure of garpenbergite.

The crystal structure refinement finally converged to R 1 = 3.7% for 957 reflections with F > 4σ(F) and 53 parameters. The experimental details and all R indices obtained are summarised in Table 4. Fractional atomic coordinates and isotropic displacement parameters are reported in Table 5. Bond distances are given in Table 7, and calculated bond-valence sums in Table 8. The crystallographic information file has been deposited with the Principal Editor of Mineralogical Magazine and is available as Supplementary material (see below).

Table 8. Bond-valence sums calculated with the site populations reported in Table 5 and according to the parameters of Brese and O'Keeffe (Reference Brese and O'Keeffe1991) for all the atoms but Sb, which was modelled with the parameters of Mills et al. (Reference Mills, Christy, Chen and Raudsepp2009).

Description of the crystal structure

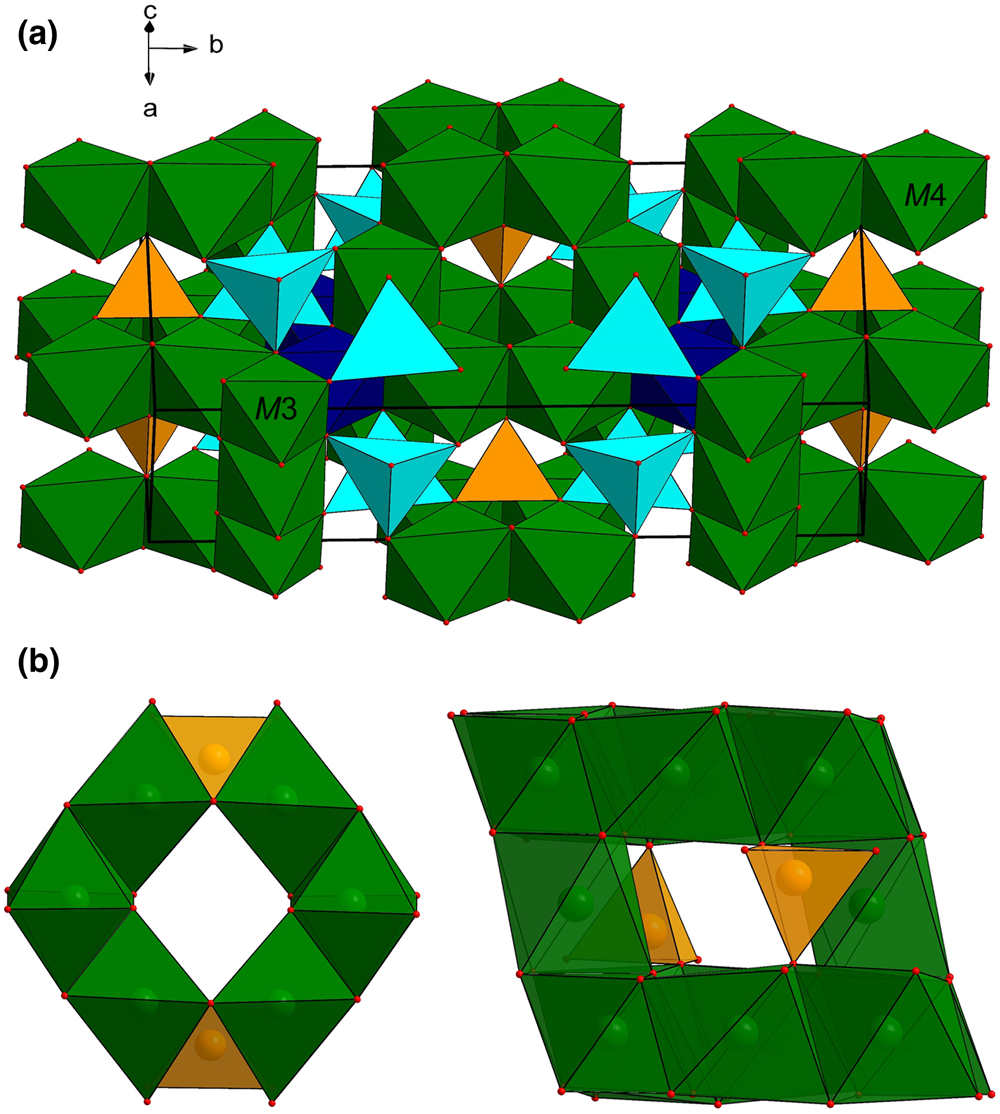

The crystal structure of garpenbergite (Fig. 3a) consists of a cubic close-packed array of oxygen atoms with layers stacked along [130], with cations occupying tetrahedral and octahedral voids in a spinel-like arrangement. The heteropolyhedral framework consists of chains of edge-sharing M4 and Sb octahedra along the b axis, connected by strips of edge-sharing M3 octahedra stretching along c. M1 (×2) and As tetrahedra sharing corners with each other in triplets, and with adjacent octahedra. The calculated bond-valance sums (Table 8) for cation sites are in good agreement with the expected formal charges of the main ionic species, Mn2+, As5+ and Sb5+. The higher value obtained for the M3 polyhedron is probably related to accumulation of Mn3+ at that site, along with some enrichment of Mg. The octahedrally coordinated M2 site, filled with Mn2+ in manganostibite, is vacant in garpenbergite (Fig. 3b). Charge-compensation is achieved by incorporation of protons in the structure. This is most likely to occur close to the octahedral vacancy, in order to obtain a favourable electrostatic situation locally. As O1 and O4 are the most under-saturated anions in the structure (1.28 and 1.79 valence units, respectively), we conclude that protonation occurs along edges of the otherwise empty M2 octahedron. The hydroxyl-stretching bands around 3600 cm−1 suggest O⋅⋅⋅O contacts > 3.0 Å (Libowitzky, Reference Libowitzky1999), in agreement with O1–O4 distances of 3.2 and 3.3 Å obtained for the present crystal structure.

Fig. 3. (a) The crystal structure of garpenbergite. The unit cell and the orientation of the structure are outlined. (b) Structural sketches highlighting the empty M2 site of garpenbergite, which is occupied by Mn in manganostibite (Moore, Reference Moore1970). Orange and light blue tetrahedra indicate As and M1 sites. Dark blue and green octahedra refer to Sb, M3 and M4 sites, respectively. Red spheres indicate oxygen atoms.

Concluding remarks

Relation with other mineral species and synthetic compounds

The structural topology of garpenbergite is nearly the same as for manganostibite (Moore, Reference Moore1970). The new mineral is derived from manganostibite via the coupled ion exchange Mn2+ + 2O2− → □ + 2(OH)–, or in vector notation, Mn2+(□H+2)–1, which leaves the space-group symmetry invariant. Notably, Ibmm is one of the orthorhombic subgroups of the Fd $\bar{3}$![]() m spinel space group (Moore and Smith, Reference Moore and Smith1969).

m spinel space group (Moore and Smith, Reference Moore and Smith1969).

Garpenbergite fits in the Strunz group 4.CA rather than 4.BA (with manganostibite; Strunz and Nickel, Reference Strunz and Nickel2001) due to a different metal:oxygen ratio (2:3 vs. 3:4). The synthetic orthorhombic phases denoted ‘spinelloid phase II’ (e.g. Ni4Al4SiO12, Ma, Reference Ma1974; Fe7.71Si1.29O12, Angel and Woodland, Reference Angel and Woodland1998) and Co7As2O12 (Barbier, Reference Barbier1997) have a close structural kinship with both manganostibite and garpenbergite. Moreover, the nesosilicate gerstmannite (Moore and Araki, Reference Moore and Araki1977a) has a metrically similar unit cell, but crystallises in the space-group Bbcm. Somewhat related are also the OH-bearing arsenosilicates holdenite (Moore and Araki, Reference Moore and Araki1977b) and kolicite (Peacor, Reference Peacor1980). Note that the overgrowth of filipstadite on garpenbergite is probably epitaxial; both minerals exhibit the spinel-structure theme with Sb5+ ions ordered at octahedral sites, and the unit-cell parameter a of garpenbergite is ⅓ × a of filipstadite (~26 Å; Bonazzi et al., Reference Bonazzi, Chelazzi and Bindi2013).

The handbook formula for garpenbergite might be written in simplified form as Mn6AsSbO10(OH)2, but at this instance, we prefer Mn6□AsSbO10(OH)2 to emphasise the close relationship with manganostibite. If the essential constituents are grouped after coordination environment (M = octahedral and T = tetrahedral), the general formula is M 6O2T 3O10 for manganostibite and M 5□(OH)2T 3O10 for garpenbergite. These minerals are part of a homologous series formalised as M 2nφn –1TnO3n+1, where n = 1 for spinel and n = 3 for manganostibite/garpenbergite, and with φ representing O2– or OH–.

Crystal chemistry

There is partial replacement of Mn by Mg and Zn in the ideal end-member formula of garpenbergite, which is apparent in the chemical point analytical data for the slightly inhomogeneous crystal (Fig. 4). It has a significantly higher Mg concentration than that known for manganostibite (1.0–2.9 wt.% MgO; Holtstam et al., Reference Holtstam, Nysten and Gatedal1998), but Mg2+ is not strongly ordered at any particular site in the structure. Garpenbergite is also comparably enriched in Zn; this element ought to be concentrated at the tetrahedral (M1) site. The M3 octahedron is axially compressed, with two short and four long M–O distances. This coordination environment is thus favourable for Mn3+ due to the Jahn–Teller interaction of the d 4 ion.

Fig. 4. Compositional variations in garpenbergite in terms of Mn vs. (Zn + Mg). The stippled line is the linear regression curve.

The Sb content in garpenbergite is close to the nominal value of 1 apfu; the situation is invariably the same for different samples of manganostibite (Holtstam et al., Reference Holtstam, Nysten and Gatedal1998). In contrast, the As site is hosting additional cations, like Si, Fe3+ and probably Mn3+. This is not unexpected, since manganostibite is shown to contain up to 0.48 Si apfu (Holtstam et al., Reference Holtstam, Nysten and Gatedal1998) and explained by considerations of electrostatic bond valances for the ideal (non-substituted) structure (Moore Reference Moore1970). The AsO4 tetrahedron may seem too small to accommodate the trivalent cations; however, limited Fe3+-for-As5+ substitution is still indicated by chemical variations in the crystal (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Compositional variations in garpenbergite in terms of As and Fe3+.

The mechanism introducing H+ in a spinel-like atomic arrangement invoked here is not unique; it is found for, e.g. high-pressure variants of MgAl2O4 spinel (Bromiley et al., Reference Bromiley, Nestola, Redfern and Zhang2010) and related compounds, like ringwoodite (n = 1) (Grüninger et al., Reference Grüninger, Liu, Brauckmann, Fei, Boffa Ballaran, Martin, Siegel, Kentgens, Frost and Senker2020) and wadsleyite (n = 2) (Deon et al., Reference Deon, Koch-Müller, Rhede, Gottschalk, Wirth and Thomas2010), and is coupled to cation vacancies at, most frequently, octahedral sites in those structures. For garpenbergite, high-pressure conditions are not inferred, but a high-${\it f}_{{\rm H}_ 2{\rm O}}$![]() environment of formation is indicated by the close association with the strongly hydrous mineral carlfrancisite. Notably, carlfrancisite from Garpenberg is very similar in composition to the holotype specimen from Kombat, Namibia (Hawthorne, Reference Hawthorne2018). We do not, however, expect to find the same paragenesis as described here at Kombat, because of insignificant Sb concentration in the ore lithologies there.

environment of formation is indicated by the close association with the strongly hydrous mineral carlfrancisite. Notably, carlfrancisite from Garpenberg is very similar in composition to the holotype specimen from Kombat, Namibia (Hawthorne, Reference Hawthorne2018). We do not, however, expect to find the same paragenesis as described here at Kombat, because of insignificant Sb concentration in the ore lithologies there.

Acknowledgements

We thank Franz Vyskytensky, Kopparberg, for providing specimens from the Garpenberg deposit over the years. Oona Appelt (GFZ) is thanked for her support with the electron microprobe work. Reviews by two anonymous reviewers and Structural Editor Peter Leverett improved the paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2022.6