Often serious-browed matrons see nude girls positioned for every kind of sex act. Vestal eyes gaze on prostitutes’ bodies, nor is that any cause to punish the owner.

In this verse, Ovid attempts to defend his Ars Amatoria against the charge that it incited promiscuity and vice in respectable matrons. He argues that both Roman matrons and even the sacred Vestal Virgins regularly encountered prostitutes, even though the Vestals lived in the Forum Romanum itself and presumably traveled only through elite and public neighborhoods. Neither the matron, the owner of the gaze, nor the objectified meretix, putative owner of her nude body, ought to be held responsible for such an encounter.

While such a claim fits earlier evidence that Ovid frequently deliberately blended the social spheres of meretrix and matrona in his work, this poem also contradicts any idea of a separate illicit red-light district.2 The popularity among modern scholars of the idea of Roman moral zoning may stem from a general contemporary view that public sex work and solicitation is inherently shameful. In particular, streetwalking and sordid brothels, which generally have a lower-class clientele, are ghettoized in the modern imagination, even while high-class escorts advertise openly for “girlfriend-type experiences” in respectable newspapers, magazines and on the Internet.3 Both the literary and the archaeological evidence in this chapter, however, demonstrate the visibility of prostitutes and the acceptable nature of their activities in the ancient Roman world. Not only men but matronae view and are viewed by meretrices; this gaze is not morally corrupting for the matron, nor does it humiliate the prostitute.

While Roman prescriptive texts clearly distinguish distinct types of women, any such separation was neither geographical nor temporal in nature. Roman matronae, meretrices, and all the women discussed in earlier chapters who transcended or transgressed these labels would have necessarily and frequently encountered each other in the Roman urban landscape. In order to construct any plausible model of such interactions, however, we need first to establish briefly how to locate these women within their physical setting.

The archaeological and literary record cannot give us any statistical sense of how many prostitutes were in a given city or where and how often they practiced their trade. While McGinn has attempted to generate a comparative set of statistics through modern brothel studies, these can give us only wide ranges of possible numbers of customers and prices.4 Furthermore, McGinn focuses narrowly on evidence from Pompeii. By also examining cities outside southern Italy and considering new criteria for identifying possible locations of sex work, we can gain a more general sense of how Roman prostitutes functioned in the urban landscape of the Empire.

Modern scholarship on the location of sex work in the Roman city has focused almost exclusively on an attempt to label and count brothels, largely within the small city of Pompeii.5 This is a search concerned, naturally, with definitions and vocabulary: what makes a building a brothel? This hunt for brothels also seeks to locate and segregate Roman prostitutes themselves: both Ray Laurence and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill have suggested “red-light districts” for prostitutes in Pompeii, separating the shameful women from the eyes of respectable matrons and maidens.6

While McGinn has recently used archaeological evidence to disprove this theory of “zoning shame” for Pompeii, this chapter establishes that prostitutes worked in highly public locations in urban areas throughout the Roman Empire.7 While meretrices certainly did not share the same social status or respect as married women, they formed a ubiquitous part of the urban landscape. Just as prostitutes formed an essential part of the community during the yearly cycle of Roman religious festivals, as shown in Chapter 7, they also played a public and visible role in the daily lives of urban citizens from Ephesus to North Africa.

Through a set of case studies of possible brothel sites in Pompeii, Ephesus, Ostia, Dougga, and Scythopolis, as well as a review of the surviving literary descriptions, we can further illuminate Roman attitudes towards prostitutes and how they functioned in Roman society. As brothels are the best archaeological proofs of sex work in areas where graffiti have not survived, this chapter will primarily concentrate on using brothels as a means of establishing the prominence of prostitutes in the urban environment and their relationship to their communities.

Limitations of archaeology: prostitution outside brothels

While our existing literary evidence does repeatedly mention and describe brothels, it also strongly suggests that Roman prostitutes were limited neither by neighborhoods nor buildings.8 As discussed in the Introduction, none of the common words for prostitutes define them with regards to a spatial context.9 The most common term used for brothel, lupanar, merely refers to a wolf-den; it does not convey any specific restrictions for location, structure, or size.

Furthermore, literary texts and the epigraphic evidence of graffiti tell us that sex work took place in a wide variety of locations including baths, graveyards, the back rooms of tabernae, and alleyways. In Roman Egypt, one of our best sources of documentary evidence for the Roman Empire, there are indications of major centres of prostitution in the larger Delta towns, as well as at Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople, but we have found no clear archaeological record of such activity at these sites.10 Similarly, no likely brothels have been found in Roman Britain or Gaul, despite the assumption that sex work must have taken place in these provinces.

The late Roman jurist Ulpian distinguishes pimps, or lenones, into two categories: those for whom selling prostitutes is a primary business and those who do it as a sideline of related businesses such as managing taverns or baths. Such a distinction suggests that sex work frequently took place in both those locales.11 Pompeian graffiti, as Clarke and Varone have shown, offer sex for sale outside the doors of relatively respectable houses like the House of the Vettii; we also find advertisements or accusations of promiscuity on apparently random walls and gates.12 Furthermore, the more prosperous freelance courtesans discussed in earlier chapters may not have had any obvious permanent signifiers of their profession at their workplace or home at all. We must assume that sex was sold in a wide variety of locations where it left no surviving archaeological evidence: by its very nature, sex work is a transitory act. In order to learn what we can about the presence of prostitutes in the urban landscape, then, we must turn reluctantly to the minority of sites which do offer relevant data: possible brothels.

Wallace-Hadrill’s brothel-identification model

Most current scholars of Roman brothels extrapolate all their conclusions from the structure, size, and decoration of the most obvious lupanares of Pompeii. This method of data collection remains constant even though these studies cannot agree about the definition of a brothel in this one town. While their conclusions are generally accurate with regard to Pompeii, they have the weakness of sifting through the same overused evidence in an effort to establish new theories.13

Wallace-Hadrill has developed a model based on his research in Pompeii and Herculaneum, which suggests that the most reliable indicators of a brothel are “a masonry bed set in a small cell of ready access to the public, the presence of paintings of explicit sexual scenes,” and a “cluster of graffiti of the hic bene futui’ type.”14 If at least two of these markers are present, he declares that the archaeologist may be justified in identifying a location as an ancient brothel. Like other scholars, Wallace-Hadrill admits that such buildings may have had multiple uses as taverns or hotels in addition to their sexual purposes.

These signifiers have obvious disadvantages and serious limitations as means of evaluating possible brothel sites. Sexualized graffiti may simply indicate that the author was contemplating sex at the time of its composition. However, a concentration of such inscriptions is certainly suggestive of nearby sexual activity if not prostitution (unless prices are advertised). Graffiti demonstrates thought, not action, and it may well be exaggeration rather than reality. We do not assume that modern public bathrooms with obscene graffiti are probable locations for sex work, rather than surfaces for explicit commentary about sex by both men and women.

Erotic art, as discussed in Chapter 5, indicates more about the artistic tastes of the owners of the room than the owners’ professions.15 For instance, the high-quality paintings of lovemaking in the Villa della Farnesina in Rome are almost certainly unconnected with the payment of money for sex acts.16 Depictions of sex in art, whether wall paintings or suggestively shaped drinking vessels, were commonly displayed in the atria and gardens of wealthy Roman households, rather than being limited to the cubicula where sexual activity presumably actually took place. Furthermore, simple images of genitalia, like the ceramic or plaster phalli frequently found on street corners in Roman towns, probably represent not advertisements for sex but good luck tokens or religious imagery. We may be simultaneously overestimating and underestimating the presence of prostitutes in the urban landscape.

Wallace-Hadrill’s reliance on visual motifs is only possible in unusually well-preserved sites such as Pompeii; it fails to be useful in sites like Ephesus that have long been exposed to the elements. As for masonry beds, the presence of these is likely to have been dependent on local building materials and styles, as there is nothing intrinsically related to prostitution about such a bed. Wooden beds may have been common and not survived the eruption in Pompeii; prostitutes may also have used straw pallets or no bed at all.17

Non-Pompeian methods of brothel identification

If we cannot rely on art and graffiti, and masonry beds may not have survived or been common in other areas of the Empire, how do we find a Roman brothel? Without knowing where the sex workers were, how can we know if they encountered respectable wives? Until now, the process has been circular: a building is defined as a brothel on its similarity to the “purpose-built brothel,” the notorious Pompeii lupanar, which in turn was identified partially based on its similarity to descriptions in Juvenal and Petronius, as discussed later in this chapter. The greatest strength of the literary texts is their implication that, while not all sex work took place in brothels, brothels were a common feature of the Roman city and a standard location for sex work.18

In order to expand our data set and produce a more useful model, I offer some additional new criteria by which to evaluate potential brothels outside of Pompeii. Locating brothels elsewhere in the Empire helps establish the prominence of Roman prostitutes in general in the urban landscape, rather than relying on the evidence of one possibly atypical town.19 Many sites previously identified as brothels, like the Ephesus Via Curetes building, have been subsequently dismissed because they did not adhere to the Pompeian canon. By comparing a variety of these other sites and supplementing the archaeological records with literary evidence, it is my hope to establish a new set of possible brothel signifiers for the Roman Empire, which can help to define sites that are not as well-preserved as Pompeii. The location and prominence of these other sites can then inform us about the spatial history of Roman prostitution more broadly.

I propose three major new criteria which, when taken together with the existing signifiers, may enable us to positively identify more brothels: a central urban location, the presence of multiple entrances, and the availability of a private or nearby public water supply. None of these criteria will produce infallible results individually, but as a whole they produce more information both about brothels and, more importantly, how prostitutes functioned in society.

All of the purported brothels discussed in this chapter contain at least one of the generally accepted brothel signifiers, such as cellae or erotic art or sexual graffiti, but their definition as brothels has remained contentious due to the lack of sufficient indicators according to the Wallace-Hadrill model.20 Besides the famous Pompeii lupanar, I will primarily be referencing four other far-flung late Imperial brothels, chosen to demonstrate the wide range of common forms: a possible brothel on the Via Curetes in Ephesus, in use during the third–fourth centuries CE, which contains erotic art and a suggestive inscription; the House of the Trifolium in the North African city of Dougga, dating from the second–fourth centuries CE, which possesses erotic art and prophylactic mosaics; the Domus delle Gorgoni from the Italian port of Ostia, from a similar time period, which has a masonry bed; and the sixth-century CE Byzantine potential brothel of Scythopolis, located in modern Israel, which preserves several erotic graffiti.

All these sites remain in relatively good states of preservation due to their abandonment in the later stages of the Roman Empire; this is the cause of the unavoidable if unfortunate focus on a later time period than the evidence presented in earlier chapters. I will briefly describe each site before moving onto the larger conclusions drawn by comparing them as a group.

Pompeii

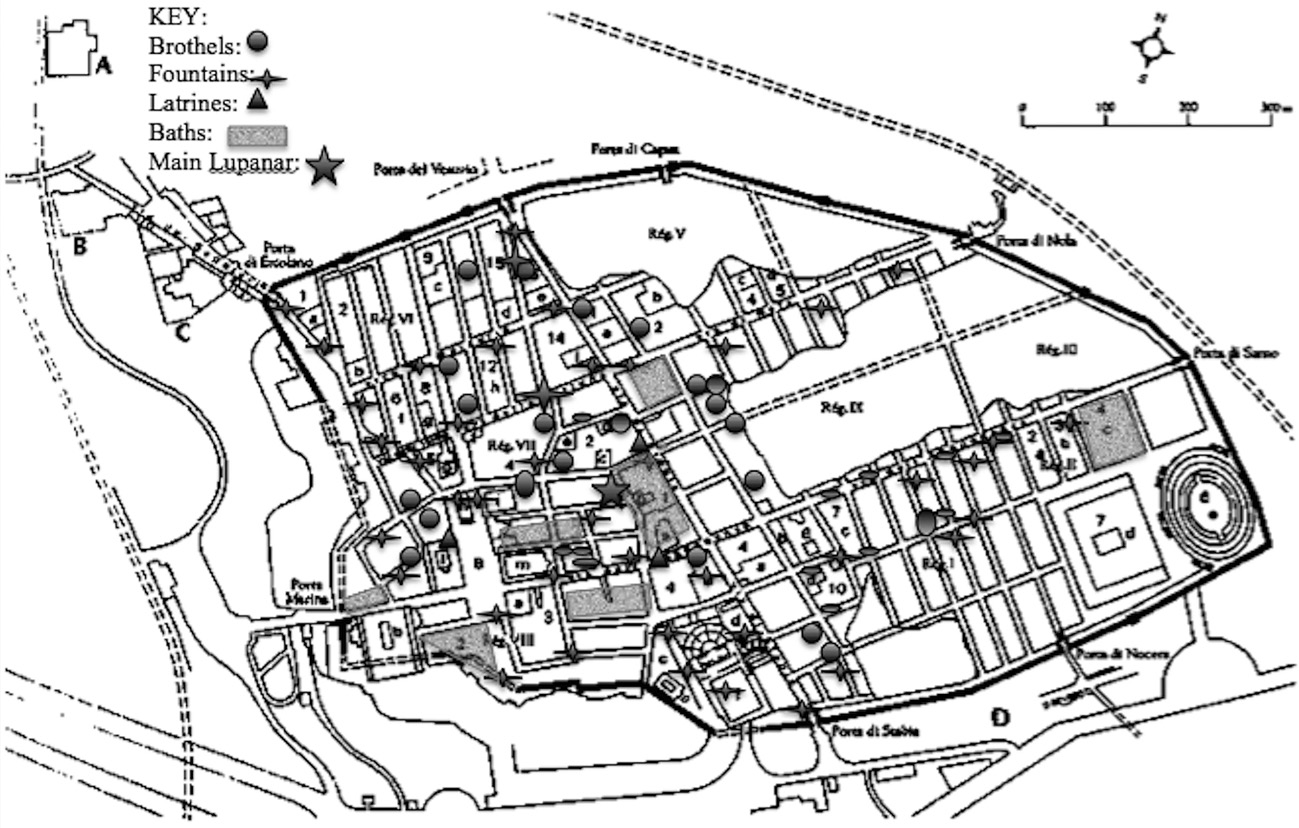

In Pompeii, over thirty of the various purported brothels, by whichever scholarly standard used, are located to the east and north of the Forum, within a five-block radius of the Stabian Baths (Figure 13).21 Wallace-Hadrill claims that “impure activities” were displaced into a hidden area of back alleys near the Forum, preserving anonymity while maintaining proximity to the Forum.22 However, this argument unnecessarily focuses on the physical brothels themselves rather than the presence of prostitutes near and around these brothels, which would certainly have intruded upon the view of any elite residents passing from, for instance, Regio VI through Regio VII to the Forum. The most famous of these sites, the main Pompeii lupanar, is located a few blocks from the Forum, near the Stabian Baths. This building has one main entrance on a side street and another, smaller entrance onto a side street. It is situated within a block of two of the local street fountains, giving it ready access to water for washing.23

13. Pompeii: map of brothels, public fountains, latrines, and baths, adapted by the author from T. A. J. McGinn, Economy, map 5.

The architectural plan of the lupanar in Pompeii’s Region VII is a narrow hallway, with five cellae on the ground floor and a wooden staircase going up to a second floor (Figure 14). Each cella contained a raised masonry bed, fairly hard and rough, with a rounded masonry pillow at one end. [Figure 15] There was a bell by the stairs, perhaps to summon the pimp, or leno, and a small latrine or washing area located under the stairs themselves.24

14. Map of the main lupanar in Pompeii (Author).

This floor plan supports the literary notion that brothels were places of work rather than primary residences for the prostitutes themselves (Figures 15, 16). The rooms are narrow and designed for sex rather than sleep, judging by the length of the beds, which averages about 5 feet (1.5 meters), significantly shorter than many of the stone or cement dining couches which have been excavated in Pompeii. There is no atrium or other public space; the building also lacks any triclinium or facility for cooking food.25 The entrances to the cellae are narrow, and there is no evidence of doorpost holes that might suggest that wooden doors formally separate the rooms from the hallway. However, hanging cloth partitions may have provided a modicum of privacy for the meretricesand their clients. It is possible that the upper floor was used for residential purposes, but site plans have not yet been fully published, and the second floor is not currently accessible to the public.26 The lupanar also has several erotic panels as discussed in Chapter 5, located in the upper wall zone above the doorways to the cellae; the north wall contains an image of a biphallic Priapus. One hundred and thirty-four graffiti decorate the inside and outside walls of the building, mostly sexual in nature or directly referring to prostitution through an association of a woman’s name and a price. They are written in both Latin and Greek and appear to be the work of both prostitutes and their customers.27

16. The main hallway of the Casa di Lupanare.

Ephesus

As you walk down the Via Curetes of Ephesus, away from the amphitheater towards the Library of Celsus, you come across a crude drawing of a foot, a heart, and a portrait of Tyche etched on a cobblestone (Figure 17). This image has historically been interpreted as an advertisement for the building on the lower left corner of the approaching crossroads, which has been controversially labeled as a brothel since its excavation.28

This major purported brothel of Ephesus lies at an intersection of the Marble Road, one of the principal streets of Ephesus, and the large Via Curetes, one of the other major roads; it adjoins the Scholastikia Baths and the city’s largest public men’s latrine and is located across the street from the Library of Celsus. The purported brothel was constructed at the same time and as part of the same complex as the latrine and the baths, although it later underwent substantial renovation.29 The more elite domestic residences are located higher on the hills and away from leisure complexes. Jobst argues that the building was a wealthy residential villa rather than a brothel, largely due to the high quality of the mosaics in the Curetes section of the house.30 However, this theory does not explain its unorthodox location or other brothel-like features.

This building has two definite entrances and a possible third one: a secluded, turning passageway next to a small corner tavern on the precise corner of the Marble Road and Via Curetes; a relatively large doorway about 6 meters from the corner on the Via Curetes itself; and a possible second-story access, now collapsed, from the neighboring large public latrine, which had an inscription in the corner closest to the brothel reading paidiskeia, or “brothels.” Unfortunately, we have lost the second floor of the Via Curetes building, so we cannot confirm direct access between the latrine and the brothel. However, this seems highly likely given the overall building structure and the graffito.31 The structure of the building is divided into two main sections: the section abutting the Via Curetes is a residential area with multiple large rooms and elegant mosaics, while the corner section of the building has two main rooms and a number of small cellae adjoining them, as well as an occluded entrance.

While the space could have been utilized as an inn, the lack of any hearth, cooking area, or thermopolium makes this option less likely than that of a brothel. For comparison purposes, John DeFelice defines hospitia, or inns, in Pompeii by the criteria of both potential sleeping areas and hearths for cooking facilities.32 Furthermore, Jan Bakker distinguishes between hotels and potential brothels in Ostia by studying thresholds with pivot-holes, since hotels tended to have doors that could be locked individually, whereas prostitutes’ cellae did not.33

The exterior doorway onto the Via Curetes possesses such pivot-holes, as does the doorway separating the two sections of the building. The four small rooms off the two main rooms of the corner section do not have them, however, implying that they were likely only shielded by curtains, which would be consistent with the identification of this building as a brothel. As Apuleius and other Roman writers frequently describe the dangers of theft in inns, it seems likely that urban hotels would have placed a high priority on lockable doors, particularly in high-profile locations like the Via Curetes.34 Other findings include a large statue of Priapus, a hip-bath, a water-spigot, and a graffito instructing visitors to “Enter and enjoy,” all highly suggestive if not conclusive evidence of part of this building’s use primarily as a brothel at certain points in its long history (Figure 18).35

Dougga

The House of the Trifolium, a purported brothel in the North African city of Dougga, is also on a major road next to a public bath and a large public latrine (Figure 19). While it is not close to the Forum or Agora as in Pompeii and Ephesus, the Trifolium House is still surrounded by other large centers of public entertainment. Furthermore, it is nowhere near any other residential buildings and is therefore not part of any typical neighborhood.

The architecture of the Dougga House of the Trifolium, which is currently being re-excavated, appears similar to that of the other purported brothels. According to its current excavators, the building was renovated on multiple occasions. Given its portico and elaborate triclinium, this edifice was probably originally an elite villa which may have been later repurposed as a brothel. The House of the Trifolium possesses the unusually occluded entrance common among other brothels; the later renovations added more small cellae, which also support the theory that this building may have been used for sex work.36

Golfetto records various “prophylactic mosaics” but unfortunately does not detail their imagery; the more recent excavations have not reached that area of the building yet.37 A prominent phallus and breasts are inscribed on the wall outside (Figure 20). While there is less evidence for this building’s use for sex work than at several of the other locations, the various architectural and locational anomalies and the presence of a variety of brothel signifiers make its identification highly plausible. The House of the Trifolium features a hip-bath and a flowing drain or shallow fountain constructed during the later renovations at Dougga, suggesting a new emphasis on water accessibility during the repurposing of the building.

20. A stone relief of phallus and breasts from the House of the Trifolium, Dougga, North Africa.

Scythopolis

The alleged Scythopolis brothel is located on the main Street of Palladius across the street from a bath complex and another latrine, in the ancient province of Judaea, now the site of Beth Shean in modern Israel. The building, also known as the Sigma Plaza or Portico, dates from the beginning of the sixth century CE, when Scythopolis was a city of 40,000 people stretching over 375 acres.38 The structure is a semicircular exedra measuring 13 by 15 meters; each half possesses six narrow trapezoidal cellae with front doors, and another row of small cellae, possibly built at a different date, stretch horizontally across the end of the exedra that faces directly onto the Street of Palladius.39 Some of the ground floor cellae also feature multiple exits, which open onto a corridor or alley at the back of the building as well as onto the courtyard.

The courtyard itself measures 21 by 30 meters. Traces remain both of an interior staircase leading to a lost second floor from one of the exedra cellae and an exterior staircase with a balcony and perhaps five more cellae on the upper floor, a pattern similar to that of Pompeii’s brothel. Three out of these five extra exits open directly onto doors leading into the neighboring baths, suggesting easy transit between the two buildings, just as in Ephesus. Two of these particular rooms, both located towards the back of the western side of the semicircle, third and fourth from the left side, contain rough remains of benches, which further supports the theory that they were used for sex work. The floors of the rooms were covered with mosaics depicting poems in Greek, animals and plants, and a Tyche crowned by the walls of Scythopolis.

This building may have had other purposes before possible conversion of some sections into a brothel, given the elegance of its furnishings. It may also have served a loftier clientele than the Pompeii Regio VII lupanar, or it may have been a larger marketplace in which only a few rooms were used as prostitutes’ cellae.40 Other suggested uses are as a marketplace or guildhall, but the lack of any trace of tools or material deposits of food makes this hypothesis difficult to substantiate positively. At the same time, its general layout is more suggestive of an open forum or market than the brothels discussed elsewhere in this chapter; it seems unlikely that it was a single-purpose structure for sex work. Unlike other such structures, it was also a more public and official building, dedicated by Silvinus, son of Marinus, the first citizen of the town, in 506/7 CE.41 Its lengthy history and later use as a Muslim cemetery may also have contributed to a lack of artifacts that might conclusively establish its usage patterns.42

While no erotic art has survived in the Sigma Portico, sexual graffiti are the primary set of evidence supporting the theory that certain rooms in this building were likely used as regular locations for sex work. In the cella featuring the Tyche mosaic, there are two graffiti: “The room of the most beautiful woman” and “I pour passion, like lightning in the eyes.” These certainly imply a romantic or sexual purpose for the rooms. An inscription in another cella further bolsters this hypothesis: “To the friends of Magus who decorated the room and amused themselves the night long with young women.”43 While this message could refer simply to a sympotic gathering, the highly public nature of the building argues against any private residential purpose for the site. The main entrance also bears an inscription, “Enter and enjoy,” which is also a prominent graffito on the Ephesus brothel. However, this particular phrase is often associated simply with inns or other places of public entertainment. It does not necessarily have a specific connotation with sex work, although it does add further evidence for the public nature of the building.

The most plausible explanation of these graffiti is that the Sigma Portico was used as a multipurpose entertainment and shopping complex, located in a central and prominent location, much like the other brothel/bath/latrine complexes discussed in this chapter. The portico’s front entrance was on the main Street of Palladius, a Roman odeon was nearby, and a bath complex was across the street. The prostitutes might have paraded on the front portico or across the street at the baths.44 At the same time, the Sigma Portico had several rooms with back doors to a narrow alley, which would enable prostitutes’ clients to enter or leave unobtrusively if desired. If indeed prostitutes worked regularly out of the Sigma Portico as late as the sixth century CE, it is further evidence that sex work remained a prominent and socially accepted part of the urban landscape even into the Christian period.

Ostia

The Domus delle Gorgoni in the Roman port city of Ostia is located on the corner of two main streets, the Cardo and Semita di Cippi, in Regio I opposite the Porta Laurentina (Figure 21). According to T. J. Bakker, “No other large ground floor building in Ostia is at such a busy spot.”45 The Domus delle Gorgoni also bears the signs of a residential villa that might have been later repurposed as a brothel.46 Multiple occluded entrances to the building are present, although not to the cellae themselves. There are also indications of a permanent bed in one of the cellae where the mosaic was not continued, leaving a blank spot, although the bed itself has not survived. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that this was one of Wallace-Hadrill’s aforementioned masonry beds. Unlike other purported brothels, both elaborate dining and kitchen facilities appear to be present in the Domus delle Gorgoni, further confusing its purpose. The building also has a large basin for water in the main courtyard, as well as several small cellae and multiple triclinia. Bakker currently argues that this structure may have served as an undertakers’ guildhall rather than as a site for sex work; his argument is plausible but not conclusive and further work remains to be done.47

In a major port city such as Ostia, the presence of prostitutes can be assumed; the architecture of the Domus delle Gorgoni suggests that they may not only have been present but plying their trade by the city gate at the intersection of two major streets. At the same time, the positive arguments for this building as an exclusive location for sex work are relatively weak compared to the other structures discussed in this chapter.

Given the nature of prostitution, any such identification of any structure less obvious than the Pompeii main lupanar will necessarily be disputed and controversial. The more useful and pragmatic approach is therefore to draw conclusions from larger commonalities and patterns among these buildings. Trying to establish conclusively all the usages of any one particular structure is likely to be unproductive. However, this does not diminish the value of examining these purported brothels as a set in comparison with the Pompeii lupanar and evidence from literary texts. Such a study helps illuminate the likely prominence of sex work in urban settings across the Empire.

Location

One common factor of all of these purported brothels is their location relative to the rest of the city, which would be highly unusual for elite residential villas. In every case, the building is located near the center of town, usually within a few blocks of the Forum or Agora. According to literary references in Catullus, Plautus, and Propertius, the prostitutes of the city of Rome frequently practiced their trade in the most public area of the city, the Forum Romanum, especially near the Temple of Castor and Pollux.48 Other popular Roman locations for prostitutes, such as Pompeius’ portico and the temple of Venus Erycina by the Colline Gate, were all highly public locales.49

These locations offer evidence for constant interaction between prostitutes and the elite classes, since senators, equites, and other Roman elites regularly traveled through the Forum and other areas of public business. Laurence’s theory that Roman elite women and children could regularly avoid contact with prostitutes of either gender is highly implausible; they were as much a part of the center of Roman life as merchants, priests, or watchmen.50 Rather than any idea of moral zoning, Roman forums and major streets would have necessitated visual contact between all types of women and men.

Of course, while women like the Empress Livia and the Vestal Virgins may have seen prostitutes, this does not mean that they interacted with them publicly or had contact with them. Matrons could demonstrate their own pudicitia precisely by ignoring the sight of disrespectable women. In Plautus’ Cistellaria, a madam complains that the upper-class matrons speak flatteringly to prostitutes in public but mock them behind closed doors, as well as restricting their access to the female social network. In this case matrons do interact with prostitutes but in socially constrained and discriminatory contexts.51 Furthermore, the privilege of elite matrons to travel in litters in cities may have meant that there was little chance that a matron and a prostitute would actually physically contact each other, even if they traveled on the same street.

Respectable women would generally be accompanied by slaves or husbands; such figures might also have provided a physical barrier between these different classes of women.52 Elite women, however, would have had to take affirmative steps to prevent themselves from seeing prostitutes, rather than prostitutes being pre-emptively exiled from respectable portions of the city. At the same time, Roman men of all social ranks had the readily available opportunity to gaze at prostitutes and purchase their favors if they desired. Furthermore, prostitutes might easily have seen the clothed bodies if not the veiled faces of matrons.

The centrality of brothels’ locations is borne out by the archaeological evidence from towns and cities across the Roman Empire, as shown in the cases of Ostia, Dougga, Ephesus, and Scythopolis, sites which seem to be plausible brothels for non-location reasons. The consistency between these locales establishes the commonality of a prominent location, usually although not necessarily near a bath and a public latrine, for brothels of the Roman Empire. This conclusion is supported by literary evidence from Rome itself, a city in which we sadly lack archaeological data about brothels. Cato the Censor famously admonished a young senatorial son about seeking prostitutes:

Some men are found only with the kind of woman who would live in a stinking brothel. When Cato [the Elder] met a man he knew coming forth from such a place, his divine sententia was, “Well done, for when shameful lust has swollen the veins, it is suitable that young men should come down here (descendere), rather than fool around with other men’s wives.” But when Cato later ran into the same young man again at the brothel, he remarked, “Young man, I praised you for going there, not for living there.”

According to this passage, the exceedingly respectable Cato was able casually to encounter someone multiple times near a brothel, suggesting that, wherever this brothel was, it was not far from Cato’s normal haunts of the Forum and the elite residences of Rome. On the other hand, the passage does imply a contrast between the areas in which Cato and other elites live and the general location of brothels, at least in Cato’s time in the late second century BCE: the brothel is a “stinking” place to which one descends. Descendere may mean that the brothels were not located on the more elite hills of Rome but in the lower-status valleys. However, the late Republican poet Catullus implies that at least some brothels in Rome are situated close to the Forum:

The Capped Brothers are Castor and Pollux, whose temple was a prominent fixture of the Roman Forum. If this literary brothel-tavern was located nine doors away, even metaphorically, it might be on the outskirts of the Subura, the Roman slums, but it certainly intruded upon the notice and gaze of the Roman elite. While this may not be a neighborhood that Roman senators dwell in, they clearly pass by it en route to the Senate each day. Catullus’ reference to “scribbling obscenities on the wall” also provides support for a link between taverns used for sexual work and obscene graffiti. Although Catullus may well be speaking metaphorically about the specific tavern, his poem does not suggest that such a location would be surprising. Plautus warned against the same neighborhood centuries earlier: “Behind the temple of Castor are those whom you should not trust too soon. On the Vicus Tuscus are people (homines) who sell themselves.”54

The Vicus Tuscus is a major street near the Forum, dominated by a statue of the Etruscan god Vertumnus. It was a center of Roman male prostitution, while the Argiletum, at the boundary between the Forum and the Subura, was a prime location for female prostitution.55 It is unclear whether the prostitutes near the Roman Forum were simply advertising their brothels deeper in the Subura or whether they actively practiced their trade against the walls of the Temple of Castor and Pollux.

Horace, addressing his own manuscript contemptuously, comments that, “Book, you seem to look towards Vertumnus and Janus, doubtless so that, scrubbed smooth by the pumice of the Sosii, you may sell yourself.”56 Such a comment potentially locates both popular bookselling and whore-selling markets in Rome between the statue of Vertumnus on the Vicus Tuscus and the Temple of Janus, at the bottom of the Forum, on the Argiletum, near the notorious Subura district.57

Prostitutes in Rome, while undoubtedly available throughout the city, thus likely centered their trade in and around the highly public area of the Forum Romanum. Prostitutes were also readily available in other places of entertainment such as the circus, the theater, especially Pompeius’ portico, and baths, as well as near the Temple of Venus Erycina at the Colline Gate.58 The consequence of the location of prostitutes’ places of business in Rome would have been high public visibility in the areas frequented by elite and wealthy men, as well as women.

This conclusion also follows simple logic. In a society where visiting a brothel, as Cato proclaims, was a deed without shame, there was no need to exile brothels outside the city walls as would occur later in medieval Europe.59 We see here a very Roman efficiency in locating brothels near other sources of public entertainment and leisure in order to allow for easy access. Neither brothels nor prostitutes, as argued in earlier chapters, were seen as being fundamentally different than bath attendants, actresses, or gladiators: all possessed the negative reputation of infamia, but all were also tolerated within society and provided opportunities for pleasure to a large section of the populace.60

McGinn’s maps show that there are no fewer than eleven brothels or cellae meretricia, including the notorious large lupanar, within a block of the Stabian Baths in Pompeii.61 The obvious difficulty with these maps, as with all the more optimistic assessments of brothels in Pompeii, is why a relatively small city needed such a plethora of locations for sex work within such a small radius, particularly given that graffiti indicate that prostitutes practiced their trade throughout the city. One likely possibility is that many of these proposed sites may have had multiple uses – small stands or shops by day, for instance, and cellae for sex work by night.

Furthermore, Wallace-Hadrill’s aforementioned criteria may overstate the likelihood that prostitution took place in all these locations. However, if even some of them were used for sex work, it would still represent a publicly prominent social role for Pompeian prostitutes. Women like the famous philanthropist Eumachia or the denizens of the conservative and wealthy House of the Faun could not have avoided passing multiple prostitutes en route to their own respectable daily activities like visiting the baths or temples.

Comparative evidence from the ancient world also supports the public location of these brothels. The most fully excavated likely classical Greek brothel to date is Building Z of the Kerameikos excavations in the Athenian Agora.62 This building would have been the first encountered by Athenians entering the Sacred Gate along the Sacred Way, a prominent path for both merchants and tourists. Its proximity to water, location, and multiple entrances are all consistent with the criteria used for Roman-era brothels. Furthermore, classical Athenian literary evidence depicts brothels as present near the Agora, the law courts, the Piraeus, and in residential areas.63 Other Greek brothel-possibilities at Delos, Thessaloniki, and Mytilene, while less well preserved, also possess features consistent with these new brothel-identifiers.64 Later comparative evidence from modern legalized brothels in Nevada and New Zealand also suggest that public locations, access to water and the presence of multiple entrances are consistently desirable features for brothels, regardless of culture or era.65

Multiple entrances and brothel furnishings

Besides a number of small cellae, another ubiquitous feature of brothel architecture across the Empire was the existence of multiple entrances, usually one on a main street and one on a side street, to allow for both public and private access. Frequently, at least one entrance will be marked by twisting corridors which block the view of the interior space beyond, directly in contravention of the principles of Vitruvius’ atrium house design. The brothel incident in Petronius’ late first-century CE Satyricon, in which the narrator enters a brothel through one door and flees through another into a “crooked, narrow alley” also supports the popularity of multiple entrances for brothels:

I took her for a prophetess until, when presently we came to a more obscure quarter, the affable old lady pushed aside a patchwork rag (centonem) and remarked, “Here’s where you ought to live,” and when I denied that I recognized the house, I saw some men prowling stealthily between the rows of placards and naked prostitutes (inter titulos nudas meretrices). Too late I realized that I had been led into a sex-house (fornicem). After cursing the wiles of the little old hag, I covered my head and commenced to run through the middle of the brothel (lupanar) to the exit opposite … . He led me through some very dark and crooked alleys, to this place, pulled out his cash, and commenced to beg me for sex (stuprum).

Petronius’ account presents a relatively clear picture of the literary idea of a brothel: it is a narrow hallway lined with nude prostitutes labeled by tituli, or placards indicating name and possibly price, offering little privacy for either prostitute or client. There are multiple entrances, one at least through “dark and crooked alleys,” and the furnishings are generally poor and dirty; the entrance is covered not by a door but by a cento or patchwork curtain. The existing purported brothels in the Roman world match this literary picture quite closely, although archaeologists may have deliberately sought out buildings that matched their memories of Petronius.

Juvenal’s sixth Satire also offers a variety of tantalizing details about the stereotypical literary representation of a brothel. In particular, it supports the hypothesis of professional, non-residential brothels. In his indictment of Claudius’ adulterous Empress, not only Messalina but all the other prostitutes leave at the end of their nightly duties to go home.66 McGinn argues that this may be a literary device necessitated by the presence of the Empress, rather than reflecting a reality in which prostitutes frequently lived outside brothels.67

However, most of the existing probable full-time brothels discussed earlier in this chapter do not contain hearths or other facilities conducive to residential life. The prostitutes may have used braziers rather than hearths or eaten outside the building, however. A dish of green beans and onions was found on the second floor of the Pompeii lupanar, but no cooking facilities, suggesting that, at most, the inhabitants brought in food from nearby taverns.68

It is unclear where these women might have slept if not at the brothel; the lost second floor of many of these buildings is one possibility, while cheap multi-person rooms in insulae are another, particularly given that prostitutes may have kept unusual work hours. While prostitutes may frequently have had sex in taverns or other residential buildings, the literary evidence at least leads us towards a plausible identification of some buildings as brothels precisely because of their lack of residential facilities.

Juvenal provides a wealth of other details about the furnishings, smell, and general poverty of Messalina’s supposed brothel:

The whore-empress, covering herself with a hood, dared to leave the Palatine and prefer a mat to a couch, accompanied by not more than a single maid. But hiding her black hair under a yellow cap she entered into a hot brothel behind an old rag and took her empty cell; then nude she exposed her golden nipples under a lying name-board of “Wolf-Girl” and displayed your womb, noble Britannicus … although exhausted by the men nevertheless she left unsatisfied, with shameful cheeks dirtied by the soot of lamps and took to the divine couch the filth of the brothel.

It is unlikely that Juvenal’s accusation of Messalina is at all accurate, particularly in the precise details, but he presumably drew his vivid imagery from the accoutrements of actual brothels, just as with his descriptions of gladiatorial games or circus races. Thus, we can note from this passage again an emphasis on the titulus or name-board, the old patchwork rag or cento which may have served as curtain, blanket, or both, the sparse furniture in the brothel, and the presence of dirt and soot. Juvenal contrasts Messalina’s own lofty social status with the degradation and crude accommodations of a brothel that closely resembles the existing archaeological remains of purported brothels.

Our other major Roman literary source for the architecture of brothels comes from a hypothetical Controversia of Seneca. In this speech, a young Roman maiden was kidnapped in a plot similar to those of the Greek novels and sold to a brothel, where she later killed her one attempted seducer. The question under debate is whether or not she could still qualify to be a public priestess despite the stain on her reputation. As part of the evidence for her shame, Seneca goes into some detail about the dynamics of her brothel:

By Hercules, you did not kill your pimp. You were led into the brothel, accepted a place, a price was fixed, the name-board was written: enquiry can go so far against you – the rest is obscure. Why do you summon me into your closet and to your lecherous little bed?

While this is obviously a general fantasy about brothel architecture and life, it can give us a glimpse at a typical pattern. The prostitute has a place in the brothel, possibly in the common area, but she also has a specific room, with her titulus, detailing a name, price, or both written above it. She is described as sleeping on a lectula in a cellula, which may reflect the small and dingy quarters present in most actual brothels. Seneca the Younger mentions curtains or coverings across cellae entrances as being a standard feature of brothels; these would obviously not have survived the millennia but may explain the lack of doorposts in places like Pompeii and Ephesus.70 Turning to the material evidence, we can see that the literary evidence for small quarters and multiple entrances is borne out by the layout of surviving brothels across the Empire.

Water and brothels

Another possible signifier of a Roman brothel is the existence of a private well or hip-bath within the building or nearby, as in the case of the hip-baths and small wells or water-troughs described in the sites above. This association of brothels with private water supplies is supported by not only archaeological but also literary evidence. Frontinus and Cicero both complain about brothels pirating the public water supply for their own usage.71 Frontinus, possibly directly quoting M. Caelius Rufus, exclaims, “we find farms being irrigated, taverns, even garrets, and finally all the brothels are equipped with constantly flowing taps!”72 Although this evidence comes from a later period and a different region, a sixth-century CE Egyptian lease from Hermopolis describes a brothel as containing both an external courtyard and a well.73 Thus we can use archaeological indications of private fountains or baths in unusual settings, such as in or near small buildings with multiple small cellae and multiple entrances, as yet another potential sign of sex work.

The association of brothels with baths and bathing appears to be true across many cultures and time periods; in medieval England the words for “brothel” and “bathhouse” were virtually synonymous.74 Why brothels would particularly desire access to private water supplies is somewhat unclear, although the combination of post-intercourse washing and a frequent literary description of Roman brothels as full of soot from lamps suggests the potential advantages of private baths. Ovid’s lover, after unsuccessful intercourse, “takes water to conceal her shame (hoc dissimulavit).”75 Martial tells Lesbia that she does not sin in “fellas et aquam potas,” fellating a lover and then drinking water afterwards.76 While neither of these examples are situated within a brothel, there is logical connection between sex that needed to be quickly cleaned up or concealed and the availability of nearby, private water supplies. In any case, the presence of such private fountains is yet another potential indicator of a brothel in towns less well preserved than Pompeii, although one to be used with care and only in the presence of other signifiers.

Separation by time

Even if matrons and meretrices walked the same streets of Ephesus and Pompeii, they may have done so at different times of day. Both literary and archaeological evidence indicate that lighting was necessary in Roman brothels.77 Three terracotta oil lamps were found in the Pompeii lupanar.78 A “very large concentration” of glass oil lamps from the Byzantine period was found in one of the rooms of the purported Scythopolis brothel, although the room could also possibly have been a lamp shop at some point.79 The presence of lamps in both textual and archaeological sources suggests at least some brothels operated at night. However, the lack of interior windows in some of the cellae in Pompeii or the other purported brothels also means that lamps might have been necessary even during the day, at least for financial transactions if not the sex work itself.

The early third-century Christian writer Tertullian repeatedly describes lanterns and the decking of porticos with leafy wreaths as a means of identifying brothels: “She will have to go forth [from her house] by a gate wreathed with laurel, and hung with lanterns, as if from some new den of public lusts.”80 Neither exterior lanterns nor wreaths would have generally survived in the archaeological record of purported brothels, rendering them largely useless as tools of identification.81 However, lamps are also problematic as a means of firm brothel identification. Terracotta and bronze oil lamps are sufficiently common in all shops that they are not specific to the profession, even in the case of oil lamps with erotic art on them, which might be more suggestive. Nonetheless, Tertullian, who lived in both Rome and Carthage, may here be providing us with an image of typical brothel advertising, along with the other literary representations of the centones or rag curtains, which have also not survived. The ornamentation of wreaths around the door or on the portico also suggests a prominent and decorative main entrance, which is consistent with both the archaeological and literary evidence.

If we accept that lamps are strongly associated with brothels and thus may indicate frequent nocturnal work hours, new questions are also raised about the effect of timing on clientele and on the public prominence of meretrices. While elite men might have had their work finished by midday and then proceeded to the baths and other entertainment centers like brothels, common craftsmen and slaves would have worked longer hours and might have needed to postpone brothel trips until the evening or night.82

Fikret Yegül argues that by the mid-afternoon and early evening, the baths became a socially mixed zone where “the wise man and fool, rich and poor, privileged and underdog, could rub shoulders and enjoy the benefits afforded by the Roman imperial system.”83 If this is true for the baths, it might well also have been true for the brothels, which would thus have offered a social mixing of clientele from varied social backgrounds, if not direct encounters between matrons and meretrices. Such a hypothesis does not restrict the possible duration of daily sex work for prostitutes; indeed, given that at the low end prostitution was not very profitable, Roman streetwalkers and brothel girls may have needed to work long hours, perhaps from mid-afternoon until dawn.

Married women, particularly elite and wealthy women, would presumably have largely remained indoors during the evening, unless traveling by litter to a dinner party. They are unlikely to have encountered prostitutes who plied their trade only by night. Juvenal seems to express disapproval of Messalina’s nocturnal wanderings as well as her destination, and Suetonius, as noted in Chapter 4, criticizes Julia for outrageous debauchery in the Forum Romanum at night.84 The case of Hostilius Mancinus and the prostitute Manilia, who drove him away from her window at night by throwing stones, as discussed in the Introduction, also took place at night.85 Manilia appears to have been a more elite and well-connected courtesan, who could refuse unwanted nocturnal clients, but presumably the aedile, however drunk, thought that a night-time solicitation was plausible.

Neither literary nor archaeological evidence, therefore, tightly restricts the probable hours for prostitution. Morning, a time when nearly all men would have been at work, was probably the least busy time or possibly even the rest time for most prostitutes. If prostitutes were active in the afternoon and early evening, however, they might well have encountered matrons returning from the baths or, in the case of non-elite women, the marketplace. Again, no clear moral segregation can be established.

Shame

The occluded multiple entrances of both these archaeological sites and the literary brothels raise questions about how much shame potentially attached to prostitutes’ clients, if not to prostitutes themselves. The archaeological evidence and previous chapters have established that prostitutes formed a ubiquitous and valued part of Roman society despite their infamia. Yet, if visiting a prostitute was an ordinary and socially acceptable act, why would the men of Ephesus feel the need to sneak in through the back door of a public latrine, or the men of Pompeii exit their brothel into a back alley? The young man in the Cato anecdote is clearly somewhat embarrassed to encounter Cato the Censor, but Cato was notorious for being far more prudish than the average Roman senator of his time. Clients clearly felt comfortable boasting about their encounters with prostitutes in graffiti all over the Roman world.

This mixture of social acceptability and shame raises the questions both of the identity of these clients and whom they might have feared to encounter as they entered or left a brothel. As established by previous chapters, adult prosperous Roman men might expect to have a reasonably satisfying sexual relationship with their wives as well as sexual access to the female and male slaves under their control. The most likely frequent clients of brothels, then, are either young unmarried men, men too poor to support families or own slaves whom they could use as sexual objects, or men unhappy with their marital relationships. Such a hypothesis certainly fits the literary evidence of poets like Catullus and authors like Apuleius.

Whom, then, would these men be ashamed to encounter if they left a brothel openly? The most logical presumption is their mother, wife, or other female family members. In a world of legal, regularly taxed prostitution, there is no particular general social stigma or infamia associated with visiting a prostitute. However, that does not erase the possibility of unpleasant familial drama or tension resulting from an encounter between a young man and his mother outside a brothel. Given the established location of these brothels, such an accidental meeting, at least during daylight hours, might be very plausible, unless these brothels had a discrete exit.

Conclusion

Neither archaeological nor literary evidence allows us to reconstruct fully the spatial presence of prostitutes in the Roman world. By combining these modes of inquiry and opening the discourse to the possibilities of new identification criteria, however, we may at least identify some plausible brothels located throughout the Roman Empire. These new data points, in turn, can allow more definite conclusions about the location and prominence of brothel workers within the urban landscape.

Necessarily, this study is blind to the vast majority of Roman prostitutes and their locations for sex work; it is limited to the most likely and public brothels throughout the Empire, and some of these sites may not have been used regularly for sex work at all. Furthermore, brothel architecture almost certainly varied with both time and location, given the long history of the Roman Empire and its vast geographical spread. I have examined potential brothels ranging from first-century CE Italy to sixth century-CE Israel; undoubtedly factors ranging from divergent architectural styles to the spread of Christianity affected their design.

It is perhaps even more surprising, then, that these possible brothels have so many features in common. While they differ in many aspects, the commonalities of multiple small cellae, prominent public location, multiple entrances, and a private water supply are all remarkably consistent, as are the presences of erotic art and graffiti in locations where these have survived. Through a careful comparison of different literary sources, we can further establish a picture of dark, sooty cellae, lit by oil lamps and separated from a common area by thin curtains. We cannot ever firmly declare that a specific building was used exclusively as a brothel, but such narrow identifications are largely irrelevant for the purposes of reconstructing a broader picture of Roman prostitutes’ spatial histories. The women themselves may be gone, but their places of work remain to tell their stories.

As the archaeological evidence suggests, prostitutes plied their trade from brothels in highly public locations in cities across the Empire, as well as in many other non-brothel locations. They were neither invisible to the eyes of elite women and men nor excluded from the public areas of civic life. Rather, prostitutes formed a ubiquitous part of the urban landscape. The material record can now support an image always implied by the works of the Roman poets. When we imagine the ancient world, whether in the form of pristine, white-marbled models or in blockbuster Hollywood films and television series, the regular, visible presences of prostitutes in and around urban public spaces ought to be a part of that picture. At the same time, the regular passage of respectable women, whether on their way to the market, escorting their children to school, or coming back from a lavish dinner party, should also be understood as an essential part of that social landscape.

By combining these two sets of gendered movements, we remove Roman women firmly from the purely domestic sphere and visualize a world in which Roman matrons and meretrices of all social strata saw and were seen by each other. Their friendly waves or shudders of disdain, conversations or glares, are only present in the very rare mentions in the elite literary record, which was rarely concerned with what Roman women said to each other. However, the archaeological evidence simply does not allow for gender, class, or moral segregation.

Furthermore, the very nature of Roman matronly pudicitia depends not only on regular encounters with strange men but on a contrast with women who do not possess pudicitia. A virtuous Roman woman regularly demonstrates her shame and modesty through ignoring naked or inappropriately behaving men, some of whom may be directly harassing her. The implication is that there are, necessarily, immodest women out there who are ogling and openly desiring such males.86 Such women, if not actual sex workers, are certainly metaphorical meretrices in the sense of Chapter 4. The Roman urban landscape becomes both a place of constant transgression and a setting where respectable women can repeatedly declare and defend their subjugation to a particular male. While the meretrices – the unowned women – do not control the streets and forums in the way that men do, they nevertheless possess the freedom to walk, to gaze, and to engage in dialogue with other citizens around them. In no way are they relegated to the hidden corners of the Roman city.