It is ironic that bureaucracy is still primarily a term of scorn, even though bureaus are among the most important institutions in every nation in the world.

The most striking fact about the Indian state is how varied its performance has been, spanning the spectrum from woefully inadequate to surprisingly impressive.

1.1 Introduction

What makes bureaucracy work, especially for the least advantaged? During a field visit to the Himalayan region in the spring of 2010, I was struck by an education official’s answer to this question. Mr. Chauhan greeted me in his office in Shimla district, the capital of Himachal Pradesh (HP). Our conversation about India’s primary education programming took an unexpected turn as he described a schooling initiative for children from the nomadic Gujjar community. A pastoral tribe, the Gujjars spent summer months in the Shimla foothills, where they reared buffalo, goats and other livestock. During winters, they migrated to the plains of Saharanpur, a nearby district in the state of Uttar Pradesh (UP), disrupting their children’s education. Local education officials experimented by creating mobile schools. The Gujjars were joined by a caravan of volunteer teachers who taught remedial classes. After a few years, the first cohort of Gujjar children from Shimla had completed primary schooling. In Mr. Chauhan’s words, “Local administration needed to mobilize teachers and parents to work side-by-side … We had to uphold the policy structure (dhancha), but sometimes we let go of it. This way, the community felt it was our (apna) school.”Footnote 1

Mr. Chauhan articulated a vision of bureaucracy that was puzzling in many ways. Mobile schooling was costly and difficult for local agencies to administer. Parental participation was hardly guaranteed, as witnessed in the floundering of so many community-based development programs. The practical steps needed to make mobile schools operational were complex and politically fraught. District administration had recruited volunteers from among the Gujjars and later appointed them as contract-based teachers. Subsequently, they were promoted as regular teachers with civil service protections. These actions broke with administrative protocol and drew criticism from teacher unions. The Indian central government’s policy framework for primary education stipulated, in minute detail, the responsibilities of state governments, but there was no mention of mobile schools or the regularization of volunteer teachers. Nor was the mobile schooling program an aberration. Similar initiatives had surfaced elsewhere in HP, often led by bureaucrats working around administrative rules.

What motivated these officials to allocate scarce resources for marginalized populations and face local resistance? Equally puzzling, I observed no comparable bureaucratic initiatives in Saharanpur, where Gujjars resided in larger numbers, possessed land and had electoral clout. Nor were bureaucrats in HP more inclined to beneficence. The administrative structures, resources and career incentives for bureaucrats across the two states were similar. My fieldwork in UP revealed that local administrators there too had tried experimenting with programs for marginalized communities. But whereas local adaptations flourished in HP, bureaucracy in UP was hamstrung by a commitment to rules, enabling some initiatives to take off, but stifling many others.

This book seeks to explain when and how bureaucracy works for disadvantaged citizens, to realize the promise of education for all. One does not have to travel to Himalayan villages to recognize the importance of these questions. To provide every child with an education is a basic duty of the modern state. Most countries have laws making primary education free, universal and compulsory. Many declare education a constitutional right. How well states fulfill these promises has a profound influence on the quality of life that people lead. In that regard, the stunning growth of publicly funded primary schooling systems in developing countries occasions optimism. The United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) program reported that primary school enrollments in developing countries climbed steeply in previous decades, reaching 91 percent of children by 2015 (UNDP 2015). The number of out-of-school children fell by almost a half, from an estimated 100 million children in 2000 to 55 million in 2015. Enrollment rates in sub-Saharan Africa rose to 80 percent, even as a staggering 40 percent of the population lives in extreme poverty. In South Asia, a region with stark gender disparities, less than seven girls attended primary school for every ten boys in the 1990s. The gender gap in enrollment has reduced considerably, reaching parity in many places.

The breathtaking expansion of primary schooling masks another disheartening trend. Millions of children remain out of school, or receive services of abysmal quality, and are effectively denied education.Footnote 2 Dilapidated school buildings, teacher absenteeism, dysfunctional classrooms, high dropout rates for girls, broken systems of monitoring and academic support, a lack of community engagement – these are the maladies afflicting government primary school systems across the world. And whereas wealthy households have exited the government system to seek private schooling, the least advantaged continue to bear the brunt of low-quality governmental services. In some places, the poor too have opted to exit, committing scarce household resources toward “low-fee” private schools, some decent, others of questionable repute (Tooley and Dixon Reference Tooley and Dixon2006; Srivastava Reference Srivastava2013).

The impressive gains, and equally alarming gaps, in primary education across developing countries provoke questions of when, why and how bureaucracies effectively deliver public services for the masses. These questions are of intrinsic importance. For observers of political life, they raise longstanding conundrums. A venerable line of thought, going as far back as ancient Greece, suggests that democracy enhances human well-being. Democratic mechanisms of popular participation, electoral competition and a free press are believed to empower citizens and make states responsive to their needs. “It is not surprising,” Amartya Sen famously contends, that “no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy” (1999, 16). Democracy’s “Third Wave” saw countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America adopt democratic institutions. Democratic accountability may have led some governments to commit more public resources to primary education and other social policies, as evidenced by cross-national studies (Lake and Baum Reference Lake and Baum2001; Brown and Hunter Reference Brown and Hunter2004; Ansell Reference Ansell2010). Yet, public spending, while critical, is hardly sufficient for producing high-quality public services (Filmer and Pritchett Reference Filmer and Pritchett1999; Nelson Reference Nelson2007).Footnote 3 Democracy, it appears, has not led states to acquire the bureaucratic capabilities needed to implement social programs effectively (Andrews, Pritchett and Woolcock Reference Andrews, Pritchett and Woolcock2017, 14–26). Famines may indeed be fewer, but illiteracy, chronic hunger and insecurity persist.

If we extend our analytic gaze beyond the high politics of state spending, to the mundane assignment of implementing public services, questions of state capacity come to the fore. Few developing country states are well endowed with what Mann (Reference Mann1984, Reference Mann2008) calls “infrastructural power,” the ability to project authority and implement policy decisions over their territories. Fewer still have institutions resembling Weberian bureaucracy (Rauch and Evans Reference Rauch and Evans2000). Institutional weakness creates an enormous gulf between the aims of public policy and its execution, between what citizens aspire to attain and what they actually get (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2011). Institutional weakness also diminishes the credibility of the state’s policy commitments, incentivizing politicians to channel resources in a particularistic fashion, to the neglect of programmatic services (Keefer Reference Keefer2007). These political dynamics are visible across the world, from Mexico to Brazil, Nigeria to South Africa, India to Indonesia and beyond. At the extreme, predatory bureaucracies license officials to extract public resources, but offer citizens few services in return. Yet, service delivery can also suffer when bureaucracies are coherent and public-minded, just as patronage politics can thrive even in well-established democracies (Piattoni Reference Piattoni2001).

The dominant pattern in developing countries is not of outright failure, but of variation in state performance. Bureaucracies display large differences in their capabilities to implement policy, both between and within countries, across different policy functions, as well as across administrative tasks within a given function. There are also striking cases of effective public service delivery within developing countries (Uphoff Reference Uphoff1994; Grindle Reference Grindle1997; Tendler Reference Tendler1997; Chand Reference Chand2006). Public services do sometimes reach citizens, even where conventional theories least predict it. The uneven performance of public services in India and elsewhere motivates the central questions of this book: How does bureaucracy implement primary education, within the least likely settings? Why do some bureaucracies deliver education services more effectively than others? What, in short, makes bureaucracy work for the least advantaged?

My answer to these questions stems from the recognition that bureaucracies are collective agencies bound by norms (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989; Ostrom Reference Ostrom2000). Where formal institutions are weak or politicized, the implementation of public services may nonetheless vary depending on the informal norms that guide bureaucratic behavior. This book takes us inside the state. It casts light on the street-level bureaucracies that deliver education in rural India (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980). I argue that historical differences in bureaucratic norms have contributed to subnational variation in the delivery of primary education across northern Indian states. Conceived as the informal rules of the game, bureaucratic norms instruct public officials on how to interpret their policy mandates and the actions deemed appropriate in fulfilling them. Bureaucratic norms also influence how officials interact with individuals and groups in society, conditioning citizen expectations and collective action around public services.

Subject to the same national policy framework, as well as common political, legal and administrative institutions, I find that bureaucratic norms have evolved differently across Indian states, with material consequences for the delivery of primary schooling. Some Indian states have secured a commitment to legalism, norms encouraging a rule-based orientation. Legalism unleashes a protective dynamic, motivating officials to uphold rules, procedures and administrative hierarchies. Other states have norms committing officials to deliberation, which stimulates a problem-based orientation. Deliberation generates an organizational dynamic centered on solving problems, encouraging officials to interpret policies in a flexible manner. These distinct types of bureaucratic norms produce very different implementation patterns and outcomes for primary education. Legalism enables officials to secure compliance with policy rules and undertake less complex tasks, such as enrollment and infrastructure provision, but it weakens their ability to monitor schools and sustain community input over time, leading to uneven implementation of services. On the other hand, deliberation enables the performance of more complex tasks, encouraging officials to adapt policy rules to local needs and sustain community monitoring, thereby improving the quality of services. I ground the argument historically, connecting the divergence in bureaucratic norms to the politics of subnational state-building. Bureaucratic norms are politically constructed and maintained through the collective strategies and relationships that have evolved between subnational politicians and bureaucratic elites, often in response to central administration.

I build and test this book’s arguments in rural north India, a setting of endemic poverty, social divisions and political clientelism. Through a multilevel comparative analysis in four northern Indian states, I demonstrate that the divergence in bureaucratic norms is a causal driver of subnational differences in the implementation of primary education. On the basis of two and a half years of comparative field research, using ethnographic methods, including 507 interviews of senior officials and participant observation with street-level bureaucrats, I trace policy implementation across multiple levels of administration, from planning decisions in state capitals to routine monitoring by district administrations, down to village-level governance by schoolteachers, parents and wider communities.

In India and elsewhere, weak institutions are expected to render bureaucracy wholly subservient, captured, or corrupt. Bureaucrats are depicted as cogs who surrender their discretion to politicians. Rarely are they seen as having political authority of their own, let alone the ability to use discretion in productive ways. This book argues for a different approach, one that brings bureaucratic institutions back into the comparative political economy of developing countries. Against overwhelmingly pessimistic predictions, I find that bureaucracy in northern India can deliver primary education effectively in some cases. Yet, the quality of services varies substantially depending on the nature of bureaucratic norms that guide public officials. In demonstrating the different ways that bureaucracy works for disadvantaged groups in society, this book sheds new light on how states promote inclusive development.

1.2 From Social Policies to Citizen Welfare: Studying the Implementation of Primary Education

The battle for welfare is often waged beyond the voting booth, at the local interfaces between citizens and the state: on school campuses, at the service counters of employment offices and inside the waiting rooms of medical clinics. Primary education occupies the empirical domain of this book, but the challenge of implementation stretches across a broader theoretical canvas. It raises more general questions regarding how states transform social policies into concrete services that improve societal well-being. Chapter 2 articulates the concept and measures of implementation used in this book. Here, I discuss the importance of studying primary education through the lens of comparative politics.

Few public institutions touch our lives more directly than primary schools. Primary education lays the groundwork for learning and skills acquisition, enlarging our life chances and prospects for mobility. Education is integral to the human capabilities that we strive to cultivate, not least of all the ability to lead a life of dignity (Sen Reference Sen1999). At a societal level, primary education contributes to a country’s stock of human capital, a recognized catalyst for productivity and economic growth (Goldin and Katz Reference Goldin and Katz2009; Barro and Lee Reference Barro and Lee2015). Beyond the transmission of skills, schools impart civic lessons and help forge our relationship to the state (Gutmann 1999; Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018). Schools are formative political spaces, where children first encounter the “imagined community” of the nation (Anderson Reference Anderson1991). Schooling is a principal mode by which states broadcast territorial control, transmit ideologies and construct citizen identities. Mass public education, Ansell and Lindvall write, “marked the first profound extension of the state’s powers to civilians” in nineteenth-century Europe and America (2013, 520). In France’s Third Republic, the state consolidated its authority in the countryside through schools, transforming “peasants into Frenchmen” (Weber Reference Weber1976).

Primary education also features prominently in political debates over redistribution and social welfare. “Full citizenship,” in Marshall’s (Reference Marshall1950) classic statement, involves the progressive attainment of civil, political and social rights. The last of these rights is arguably the most difficult to realize. The provision of mass education has been an important ingredient in the protection of social rights, predating social insurance and other welfare measures (Iversen and Stephens Reference Iversen and Stephens2008, 603). The American school reformer Horace Mann proclaimed that public education is “the great equalizer of the conditions of men,” a pathway for social mobility.Footnote 4 Today, early child education is seen as a pivotal policy mechanism for combatting inequality (Chetty et al. Reference Chetty, Friedman and Hilger2011). Yet, education has also been a great discriminator within society, “hugely important,” Bourdieu observed, “in the affirmation of differences between groups and social classes, and the reproduction of those differences.”Footnote 5

For all of these reasons, primary education is a core public function and parameter for judging state performance. Yet, compared to other state functions, such as national security, regulation and industrial policy, we know far less about the politics of when, why and how states provide primary education. “The scholarly literature at this point is almost a tabula rasa on these scores,” Moe and Wiborg (Reference Wiborg, Moe and Wiborg2017, 4) write. The status of education research in other social science disciplines offers a lesson in contrasts. The economics of education has made strides following the pioneering work of Schultz (Reference Schultz1961) and Becker (Reference Becker1964), from macroeconomic studies of human capital growth to rigorous, microlevel evaluations of education policy.Footnote 6 Another fertile field, the sociology of education has illuminated the linkages between schooling and social stratification. Education research has spawned new sociological theories, such as social capital, influencing the study of politics and development.Footnote 7

To be sure, the comparative politics of education is not an empty field.Footnote 8 Research under the “Varieties of Capitalism” rubric has explored national patterns of skill formation, demonstrating how systems of higher education and vocational training complement economic institutions and shape inequalities (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Thelen Reference Thelen2004; Iversen and Stephens Reference Iversen and Stephens2008; Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2014). Yet, less is known about the politics of primary education, an institution that touches more lives and has its own distributional politics.Footnote 9 Moreover, attention to national systems and cross-national spending patterns has eclipsed subnational-level research on policy implementation. The need to study implementation is pressing, perhaps more so in developing countries, where the institutional challenges of providing quality services are enormous (Corrales Reference Corrales, Benavot, Resnik and Corrales2005; World Bank 2018). Research from developing countries also reveals the weak correlation between school spending and outcomes, such as student learning (Hanushek and Woessmann Reference Hanushek, Woessmann, Hanushek, Welch, Machin and Woessmann2011; Pritchett Reference Pritchett2013).

Problems of implementation are not, however, unique to developing countries. The United States enacted far-reaching education reforms in the early-twentieth-century Progressive Era, but it struggles to provide quality education till this day. A crowded menu of reforms for urban school districts has yielded modest results (Hess Reference Hess1999). More than sixty years after the US Supreme Court declared racial segregation unconstitutional in its landmark decision on Brown v. The Board of Education, the legacy of racial discrimination continues to be felt in American schools. Resource disparities between school districts are an obstacle, but public spending patterns do not fully explain educational inequalities (Hanushek Reference Hanushek2010). In the state of Connecticut, for instance, the towns of Bridgeport and Fairfield spent, respectively, $14,000 and $16,000 per student during the 2014–2015 academic year, above the national average of $10,800. And, whereas 94 percent of high school students in Fairfield graduated on time that year, only 63 percent did so in Bridgeport.Footnote 10 These sharp differences between neighboring school districts within a single US state are a reminder that, even in wealthy countries, policy implementation can have profound consequences for social welfare and inequality.

1.3 The Puzzle: Primary Education in Northern India

This book investigates the delivery of primary education in rural north India, an unlikely setting for public services to function well. Chapter 2 presents comparative indicators to illustrate the large subnational differences in education within this region. India historically has earned accolades for its democracy, marked by competitive elections, high voter participation and smooth transfers of power. Stable democracy is an achievement given India’s income level and extraordinary ethnic diversity (Varshney Reference Varshney2014). Between elections, however, citizen experiences of the state leave much to be desired (Corbridge et al. Reference Corbridge, Williams, Srivastava and Véron2005; Gupta 2012; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018). Bureaucracy can be apathetic and capricious in its treatment of disadvantaged citizens, prompting scholars to ponder why India’s poor even bother to vote (Ahuja and Chhibber Reference Ahuja and Chhibber2012). Wearisome encounters of the state are matched by dismal human development outcomes. India accounts for 15 percent of the world’s population, but it is home to 37 percent of global illiterates (287 million people). Indian adults complete 5.4 years of schooling on average, less than citizens in poorer countries such as Haiti, Honduras, Nigeria and Zimbabwe. India’s literacy rate of 74 percent in 2011 was surpassed by China more than twenty years prior, despite India having a lead at independence. India’s woeful human development performance is not confined to education (Drèze and Sen Reference Drèze and Sen2013). The United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) presents a composite measure of well-being based on indicators for education, health and per capita income. India’s HDI ranking of 131 (out of 188 countries) places it between Namibia and Honduras, far below other BRICS – Brazil (84), Russia (52), China (85) and South Africa (114) – the large emerging economies with which it is often clubbed.Footnote 11

India’s failure to provide quality public services is not for want of resources. Illiteracy and hunger have persisted despite three decades of robust economic growth and notable reductions in poverty (Kohli Reference Kohli2012). Income disparities have also grown, leaving the country looking “more and more like islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa” (Drèze and Sen Reference Drèze and Sen2013, ix). Nor does an absence of political will explain these deprivations. With economic liberalization in the 1990s, state control of the economy receded, but social programming expanded, substantially in some areas. Public spending on education, a paltry 1 percent of GDP in the 1970s, reached 4 percent by the 1990s. In 2000, the central government enacted Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, its flagship “Education for All” program, providing infrastructure and incentives to improve access in underserved areas. The Midday Meal Programme, the world’s largest child nutrition intervention, provides a free daily meal in more than 2 million government schools. The 2010 Right to Education [RTE] Act places a legally enforceable duty on the state to guarantee free and compulsory education for all children of ages 6 to 14 years. Not all developing countries have such progressive social legislation.Footnote 12 Yet, the pervasive deficiencies in implementation have been well documented (PROBE 1999). According to a World Bank study, 25 percent of government teachers are absent from school on a normal workday (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Muralidharan, Chaudhury, Hammer and Rogers2005).Footnote 13 A national survey reports that less than half of rural fifth graders can read from second grade textbooks, to say nothing of their comprehension or critical thinking skills (ASER 2015).

This bleak picture at the aggregate level masks substantial differences across Indian states. This book analyzes the puzzling variation in primary education outcomes in northern India’s Hindi belt, a least-likely setting for programmatic policies to reach citizens. Social divisions and clientelistic politics are thought to emasculate service delivery within this region. Nevertheless, some states in the Hindi belt perform far better than expected, surpassing the educational performance of wealthier states in southern and coastal India, while others show sluggish and uneven progress. Subnational differences in implementation exist despite a common national policy and legal framework for primary education, as well as similar electoral institutions and administrative structures. A socioeconomic laggard, UP is among the places where conventional theories least expect public services to be well-implemented (Drèze and Gazdar Reference Drèze, Gazdar, Drèze and Sen1996; Mehrotra Reference Mehrotra2006). Since the late-1990s, however, UP has experienced a dramatic upsurge in primary schooling, recording rapid growth in infrastructure, provision of the midday meal, and other inputs. By 2015, the enrollment rate in primary schools surpassed 95 percent. UP’s literacy rate also grew substantially, from 56.3 percent in 2001 to 69.7 percent in 2011. Long considered a development failure, the state of Bihar has made surprising gains as well in primary school enrollments and infrastructure provision (Singh and Stern Reference Singh and Stern2013). At the same time, services in UP and Bihar are irregular and the quality of education woefully inadequate, evidenced by poor learning outcomes.

The puzzles of this book extend to the Himalayan region, where the state of HP stands out as a leader in primary education within India. It lags only behind Kerala, a recognized model of social development in South Asia. HP’s educational achievements are even more remarkable than Kerala’s in many ways. HP’s mountainous topography, harsh climate and low population density make the administration of services far more challenging. At independence, Kerala had a substantial lead in literacy (47.2 percent) over the rest of India, whereas HP (at 8 percent) was among the least literate states in the country. Since the 1980s, HP has surged ahead of other states, with educational gains broadly shared by women, lower castes and tribal populations (World Bank 2007). The puzzle of HP’s superior performance deepens when compared to other parts of the Himalayan region. The adjacent state of Uttarakhand, which has similar economic and sociocultural characteristics to HP, performs markedly worse in primary education, even though it had a substantially higher literacy rate (19 percent) around independence.

What explains the exceptional performance of primary schooling in HP? Why does Uttarakhand’s education system fare much worse, despite its similar geographic, economic and sociocultural features, as well as an historic lead in literacy? What, moreover, explains the uneven implementation pattern in UP? Given UP’s social inequalities, clientelism and fractured political commitment to primary education, how has the state managed to improve school access and infrastructure? Why do the same state institutions falter in providing quality services? And finally, what accounts for Bihar’s notable gains in education? Why has robust political commitment for education in Bihar not also translated into quality services? These puzzles from India’s primary education sector raise larger theoretical questions about state capacity and public service delivery in developing countries.

1.4 The Limits of Existing Explanations

To make sense of the aforementioned puzzles, I consulted a vast political economy literature on the state and human development. According to a prominent school of thought, modernization and economic development lead to improvements in public service delivery and attendant social outcomes (Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Przeworski and Limongi Reference Przeworski and Limongi1997). As an economy develops, the state accumulates resources and citizens acquire new preferences and abilities to demand primary education (Meyer, Ramirez and Soysal Reference Meyer, Ramirez and Soysal1992). Some posit a virtuous cycle between growing affluence and good governance. Economic growth, the logic goes, leads to increased social spending as well as improvements in bureaucratic quality (Kurtz and Schrank Reference Kurtz and Schrank2007). Though the direction of causality is much debated – does growth lead to good governance, or vice versa? – higher income polities are expected to enjoy more and better quality public services.

With the acceleration of economic growth, social spending in India increased significantly in the 1990s. However, implementation of social programs is uneven and services remain “yoked to local public administration with weak capabilities” (Kapur, Mukhopadhyay and Subramanian Reference Kapur, Mukhopadhyay and Subramanian2008, 38). Several lower-income states in India have made substantial gains in primary education and other aspects of human development, outperforming wealthier states (Drèze and Sen Reference Drèze and Sen2002, Reference Drèze and Sen2013). Income growth cannot account for why an economic laggard like UP made notable gains in enrollment and infrastructure provision, while performing quite inadequately on other dimensions of implementation. Nor does rising income explain why services in UP’s more affluent western belt are no better than in poorer parts of the state. Likewise, modernization does not explain why HP, a subsistence-based agricultural economy with little industrial production, outperforms other states, including Uttarakhand, which has a similar level of income and higher levels of urbanization and industrial development.

A second line of thinking assigns causal weight to geography and the natural environment (Nunn and Puga Reference Nunn and Puga2012). Herbst (Reference Herbst2000, 13) highlights the “challenges posed by political geography” in Africa, such as low population density and physical terrain, to explain the state’s uneven capacity. O’Donnell likewise contends that in emerging democracies, “the authority of the state fades off as soon as we leave the national urban centers” (1993, 1358). Accordingly, Krishna and Schober (Reference Krishna and Schober2014) analyze the spatial “gradient of governance” in India and observe that villages further away from urban centers perform worse on multiple dimensions of governance. Village population density has a positive effect on access to public goods, suggesting that “ease of delivery” is a criterion for state provision (Banerjee and Somanathan Reference Banerjee and Somanathan2007, 304). Emphasizing administrative costs and political barriers for implementation in rural locales, this research reaffirms Bates’ (Reference Bates1981) argument of an urban bias in development. Recognizing geography’s importance, the empirical cases in this book were selected to control for terrain and population density. HP performs better than other states despite comparatively low urbanization and population density, scattered settlement patterns, unfriendly climate and terrain, making it costlier to provide services. The limits of geographic explanations become apparent in the case of Uttarakhand, which performs markedly worse than HP despite similar physical characteristics.

A third branch of scholarship argues for the causal primacy of institutions (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). The formal structure of constitutions, electoral systems, rules of federalism and executive power help explain cross-national variation in social spending and welfare outcomes (Huber, Ragin and Stephens Reference Huber, Ragin and Stephens1993). Yet, formal institutions cannot account for variation in the performance of subnational bureaucracies operating under a common legal, fiscal and electoral framework. A distinct strand of institutionalist literature studies the long-term effects of colonial rule on development. Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006) find that variation in settlement patterns of European colonizers influenced the adoption of institutions, producing lasting effects on economic performance. On similar lines, Banerjee and Iyer (Reference Banerjee and Iyer2005) observe the impact of India’s colonial land institutions on the provision of health and education. Regions historically subjected to zamindari, a system granting upper caste landlords authority over revenue collection, perform worse than places under ryotwari, where revenues were drawn directly from cultivators. Landlord–peasant relations in zamindari regions display persistent caste conflict, hampering collective action for public goods.

This book’s empirical strategy takes colonial institutional legacies into careful consideration. My comparative cases include localities with similar (and different) types of colonial land administration, a research design that yields unanswered puzzles. I compare districts of HP and Uttarakhand having similar histories of direct British rule and military recruitment, but different contemporary patterns of education service delivery. I also examine districts of UP with different colonial land tenure systems, but similar implementation patterns. This approach does not negate the importance of colonial land institutions. It does suggest, however, that implementation is not simply the byproduct of a colonial past but tied to political and administrative activities in the postcolonial period.Footnote 14

In sum, while prominent explanations help us understand important aspects of bureaucracy and implementation, they do not adequately address the puzzles of this book. The factors considered briefly thus far – economic development, geography, formal institutions and colonial administrative legacies – are important, but they do not fully explain variation in how states in northern India implement primary education. A new theory is needed that moves past the distant correlates of state capacity to illuminate how bureaucracy works in practice and relates to citizens on the ground.

1.5 The Argument in Brief

What, then, allows bureaucracies to implement primary education (more or less) effectively? Chapter 2 presents the book’s theory of implementation, connecting differences in bureaucratic norms to variation in policy implementation and related outcomes for primary schooling. Bureaucratic norms are unwritten rules governing the orientations and behaviors of state officials. I argue that bureaucratic norms drive policy implementation through two channels. First, they influence the collective understandings and behaviors of officials. Given resource constraints and multiple policy rules, norms allow bureaucrats to interpret policy problems in a practical sense and determine what it means to solve them. Second, bureaucratic norms stimulate societal feedback by shaping the ordinary interactions between frontline officials and citizens. As citizens gain exposure to the local state, their experiences condition future expectations and the collective monitoring of schools, impacting the quality of services.

Drawing inspiration from interdisciplinary literatures in institutional theory, public administration and political philosophy, I argue that differences in bureaucratic norms have varying material consequences for the implementation of public services. Chapter 2 develops an analytical typology of bureaucratic norms and theorizes their effects on policy implementation. I conceptualize policy implementation based on the tasks involved in delivering services like primary education. I demarcate tasks according to their varying degrees of administrative and political complexity and create a measurement scheme sensitive to the empirical context of education in rural India. I propose two ideal types of bureaucracy governed by different sets of norms, which I refer to as “deliberative” and “legalistic,” and theorize the mechanisms whereby each ideal-typical bureaucracy influences policy implementation.

I develop and test the argument in Chapters 4–7. Based on empirical materials from northern India, I connect differences in bureaucratic norms to subnational variation in implementation processes and outcomes for primary education. My comparative field research shows that deliberative bureaucracy fosters a problem-based orientation among state officials, encouraging flexibility in the interpretation of rules and robust coordination across organizational boundaries. Lower-level bureaucrats learn to discuss problems collectively with senior officials, transmitting local knowledge into hierarchical decision-making. Legalistic bureaucracy, by contrast, encourages officials to adopt a rule-based orientation, maintaining a strict interpretation of policy and well-defined organizational boundaries. Lower-level officials treat policy rules as binding constraints and seek hierarchical guidance on how to apply policies in particular cases.

Against much received wisdom, I demonstrate that legalistic bureaucracy leads to uneven policy implementation. Bureaucratic commitment to rules enables state officials to challenge political interferences, facilitating gains in enrollment and infrastructure provision. However, the bureaucracy’s emphasis on rule compliance undermines monitoring of services and other complex tasks, which involve contextual information and repeated state–society interactions. Legalistic bureaucracy supports societal participation in service delivery through official channels, such as administrative grievance procedures, enabling community oversight of schools. However, these channels create administrative burdens for marginalized groups and tend to reinforce inequalities. Over time, societal input tends to become episodic and fragmented, leading to lower quality services. By contrast, I show that deliberative bureaucracy enables officials to undertake complex tasks and adapt policies to varying local needs, which yields higher quality services. Deliberation encourages officials to identify pragmatic answers to policy problems. Deliberation also widens the scope for societal participation in service delivery by fostering public discussions in more diverse spaces, helping to integrate rural women, lower castes and other marginalized groups in the routine monitoring of schools. I develop these arguments through subnational comparative field research. Analyzing implementation in the Gangetic plains (Chapters 4 and 7) and the Himalayan foothills (Chapters 5 and 6), I demonstrate how the theoretical framework distinguishing legalistic and deliberative bureaucracy is robust to differences in agrarian economies, political party systems and caste and gender norms.

If divergent bureaucratic norms lead to variation in the delivery of primary schooling, what causes the divergence in bureaucratic norms? To answer this question, I examine the historical process of subnational state-building, tracing the political origins and persistence of bureaucratic norms across time. I argue that bureaucratic norms get consolidated in the state-building process based on the collective incentives and strategies of governing elites. Periods of relative political stability offer windows of opportunity for governing elites to establish bureaucratic norms. Once introduced, bureaucratic norms are reinforced through the emergent relations between political and bureaucratic leadership. Where subnational state politicians and bureaucratic elites had incentives to compete for authority and resources, legalism became the dominant mode of bureaucracy. Under the threat of subversion from political forces, bureaucrats used administrative rules to protect bureaucratic authority from political interference. On the other hand, where political and bureaucratic leadership had strong incentives to cooperate for authority and resources, norms encouraging deliberation took hold within the bureaucracy. Faced with the acute necessity to join hands, bureaucrats learned to deliberate to solve collective problems. The empirical cases in Chapters 4–6 show that the consolidation of bureaucratic norms happened prior to the introduction of universal primary education policies and was exogenous to the political decision to expand primary education.Footnote 15 Once established, I find that bureaucratic norms can withstand to political changes and shifting policy commitments. I also examine processes of norm change (Chapter 7), reveals the commitment of frontline agents and the conflicts they experience.

1.5.1 Building State Capacity for Inclusive Development

This book’s arguments contribute to theoretical debates surrounding the question of how states promote inclusive development. The need to make development more inclusive finds expression in Sen’s (Reference Sen1999) capability-centered approach. Sen challenges development theory’s conventional emphasis on capital accumulation and reorients it toward the expansion of human capabilities, indicated by broad-based improvements in health, education and well-being. More than mere recipients of government services, marginalized citizens are conceived as agents having a political voice in the development process. This reorientation carries political implications for bureaucracies, who in addition to providing services must enable societal participation during service delivery (Evans and Heller Reference Evans, Heller, Leibfried, Evelyne, Lange, Jonah, Nullmeier and Stephens2015). Sen’s normative formulation of what states ought to do needs to be complemented with an analytical framework for what states can do to make development more inclusive. Here, Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1996) theory of “coproduction” elegantly brings state–society relations to the fore, suggesting that states can draw productively from a constellation of non-state actors. Coproduction is not only a technique of governance but also a set of institutionalized relationships between the state and society, with attendant power differences and conflicts (Joshi and Moore Reference Joshi and Moore2004).

The “Sen-Ostrom vision” is transformative, Evans, Huber and Stephens (Reference Evans, Huber, Stephens, Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017) suggest, but it raises questions about what kinds of bureaucratic arrangements support inclusive development. This book aims to help answer these questions. Bringing diverse scholarly traditions into conversation, my argument connecting bureaucratic norms to policy implementation advances literatures on state capacity, social welfare and public service delivery. Modern states are responsible for multiple policy functions. They have to protect external borders, maintain internal order and security, regulate the economy and provide public goods. As Skocpol writes, states must possess multiple “capacities” (emphasis in original), the study of which requires sector-specific analysis (1985, 17). In developing countries, Kohli (Reference Kohli1987, Reference Kohli2004) adds, states need to facilitate income growth and poverty alleviation. Accordingly, the “developmental state” literature has shown how states promote industrial development and rapid growth (Haggard Reference Haggard2018). Autonomous, Weberian bureaucracies have played an integral part in this process. Along with autonomy, Evans (Reference Evans1995) suggests, developmental states are embedded in networks, facilitating coordination with industrial capitalists.

Developmental state scholarship has shed much-needed light on bureaucracy’s contributions to economic growth. However, the inclusive development agenda calls attention to the welfare needs of mass publics, which present different challenges for the state. Bureaucracies have to penetrate hard-to-reach geographies and coordinate with society on a much larger scale. To sustain coproduction of services, bureaucracy cannot always rely on preexisting societal networks, which can be fragmented or exclusionary (Mansuri and Rao Reference Mansuri and Rao2013). Instead, bureaucracy needs to seek out marginalized groups and counter entrenched inequalities to secure their participation. To undertake these tasks, state agencies have to motivate “street-level bureaucrats,” who possess wide discretion over the interpretation of policy rules (Lipsky Reference Lipsky1980).

Another vast literature, on clientelism and distributive politics, is less optimistic about bureaucracy’s ability to promote inclusive development (Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Hicken Reference Hicken2011). In contrast to high-powered agencies overseeing industrial policy, quotidian bureaucracies that deliver social services tend to lack Weberian characteristics and are more often enmeshed in particularistic exchanges (Grindle Reference Grindle2012; Brun and Diamond Reference Brun and Diamond2014). Rather than being a source of capability, bureaucratic discretion in the latter instances is associated with political interference and capture (Piore Reference Piore2011). Institutional reforms designed to motivate frontline bureaucrats and curb malfeasance, through pecuniary rewards and monitoring, have shown mixed results (Pepinsky, Pierskalla and Sacks Reference Pepinsky, Pierskalla and Sacks2017).

To secure the kind of bureaucratic initiative that inclusive development requires, “getting the incentives right” is not enough (Levi and Sherman Reference Levi, Sherman and Clague1997, 332). Where formal authority structures are comparatively weak, the informal rules of the game can help bolster bureaucratic commitment (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Bureaucratic norms bind officials to a common purpose. They provide a shared grammar to make sense of policy mandates and negotiate conflicts on the job, eliciting commitment to collective goals. The nature of these commitments can vary, however, and their efficacy depends on the administrative task at hand. Deliberative bureaucracy’s advantages stem from its ability to solve complex problems, which call for repeated interactions between officials and coordination across different levels of the state.

State action is essential but insufficient for realizing inclusive development. My theorization of societal feedback arises from the need for “bottom up” collective action as well (Banerjee, Iyer and Somanathan Reference Banerjee, Iyer, Somanathan, Schultz and John2007), which is particularly challenging to sustain in settings of inequality (Heller and Rao Reference Heller and Rao2015). I build on the insights of the “policy feedback” literature, which suggests that policies can have varied political effects on citizen perceptions, interests and mobilization over time (Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Mettler Reference Mettler2002; Campbell Reference Campbell2005; Kumlin and Rothstein Reference Kumlin and Rothstein2005; MacLean Reference MacLean2010). Showcasing how bureaucratic norms induce varied responses from society during implementation, my argument brings the literature on policy feedback into dialogue with public administration research on local state–society interactions (Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014). I suggest that legalistic and deliberative bureaucracies offer different administrative channels for societal participation in service delivery. These channels create distinct learning opportunities for marginalized citizens (Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2001), as well as administrative burdens when they attempt to monitor services (Herd and Moynihan Reference Herd and Moynihan2018), which has ramifications in turn for how they “see” the state (Corbridge et al. Reference Corbridge, Williams, Srivastava and Véron2005).

1.6 Research Design and Methodology

This book’s theory was developed and tested using a multilevel comparative research design. I trace the implementation process from political centers down to rural districts, villages and primary schools. This section explains the rationale for multilevel comparisons and my case selection strategy. It gives an overview of the qualitative data collected from ethnographic fieldwork, including participant observation, in-depth interviews, oral histories and focus group discussions. A detailed exposition of field methods, including information on research sites and the selection of study respondents is contained in the Appendix.

1.6.1 Multilevel Comparative Analysis

Comparative scholarship on social policy has identified the state as the chief actor in service provision (Heclo Reference Heclo1974; Esping-Anderson Reference Esping-Anderson1990; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992).Footnote 16 While revealing important cross-national patterns, less attention has been accorded to subnational variation in the implementation of services. Yet, countries display large subnational differences in social welfare provision and outcomes. Studies have leveraged subnational comparative research designs fruitfully to explain these variations (Weitz-Shapiro Reference Weitz-Shapiro2014; Singh Reference Singh2016). Subnational comparative research has shed light on wide-ranging phenomena, from economic development and public goods provision to voting behavior and ethnic violence (Snyder Reference Snyder2001).Footnote 17 Subnational comparison allows us to hold constant explanatory factors that are shared by subnational political units (e.g., regime type, constitutional-legal framework, national policies and formal state institutions) that can plausibly affect implementation. Taking subnational comparison one step further, this book’s methodological approach embraces multilevel comparative analysis, which involves the theoretically guided study of decisions and actions at multiple jurisdictions of the state. Combining controlled comparisons with systematic process-tracing, it aims to uncover the causal mechanisms for multilevel processes, such as policy implementation, and explain variation in outcomes.

My approach answers the need to examine interrelationships between levels of the state, as well as between state and society. Bringing the vertical dimension of governance into focus, multilevel comparative analysis offers advantages for the study of policy implementation.Footnote 18 First, it addresses the empirical reality of public service delivery in much of the world. In recent waves of decentralization, countries have transferred political and administrative authority to lower-level jurisdictions. Yet, the intergovernmental balance of power is not settled by constitutional edict. Decentralization is politically contested, shifting and often incomplete (Falleti Reference Falleti2010). In a multilevel federation such as India, Sinha notes, “policy implementation is the product of intergovernmental interaction” (2003, 466).Footnote 19 Administrative processes operating across tiers of the state invite opportunities for coordination as well as conflict.

India’s social policy sector is a prime example of contested decentralization. Federalism under India’s constitution grants state (or provincial) governments primary authority to legislate and implement social policy. A constitutional amendment in 1976 placed education policy under the joint legislative jurisdiction of the central and state governments. Since then, India’s central government has enlarged its bargaining power and administrative presence, using centrally sponsored programs, discretionary fiscal transfers and other mechanisms to gain political leverage over state governments (Chhibber, Shastri and Sisson Reference Chhibber, Shastri and Sisson2004; Tillin Reference Tillin, Choudhry, Khosla and Bhanu2016). State governments hold chief authority over the implementation of primary schooling, but they do not have free rein. They are constrained from above by central administrative oversight and resource allocations. They also depend on the cooperation of frontline bureaucracies. To reach citizens, social programs have to pass through the “eye of the needle,” which is the local district administration (Kapur and Mukhopadhyay Reference Kapur and Mukhopadhyay2007).Footnote 20 In addition, the 73rd and 74th Amendments to India’s constitution, enacted in 1992, devolved authority to Panchayati Raj Institutions, elected village and municipal councils, a new layer of local authority over public goods and services.Footnote 21

Multilevel comparison opens new theoretical and methodological avenues as well. The tension between “top-down” control and “bottom-up” discretion by frontline agents is a recurring theme in policy implementation research (O’Brien and Li Reference O’Brien and Li1999). In a parallel debate, the political economy literature explores the relative importance of state initiatives from above and societal collective action for public goods provision (Banerjee, Iyer and Somanathan Reference Banerjee, Iyer, Somanathan, Schultz and John2007). These tensions reflect the fact that authority is situated in more than one place. The state has “many centers of decision-making that are formally independent of each other,” but the extent to which they “actually function independently, or instead constitute an interdependent system of relations” is an empirical question (Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961, 831). Studies concentrating on elite decisions, at the national (or subnational) level, risk overstating the power of the “center,” omitting authority-holders in the “periphery” who can refashion policy in unanticipated ways. On the other hand, attention to the micro-politics of implementation risks neglecting the background institutions that can impact the work of street-level bureaucrats. Multilevel comparison calls attention to how different nodes of state authority interact to influence policies and politics. This relational treatment of the state also has methodological advantages. Investigating implementation over multiple tiers of the state increases the number of observations as well as the variety of sociopolitical contexts in which causal mechanisms are tested. Different observable implications of a theory can be probed, allowing multiple forms of evidence to corroborate or falsify causal hypotheses (Gerring Reference Gerring2004). Theory testing against rival explanations at different units of analysis helps to refine and strengthen the robustness of causal claims.

1.6.2 Case Selection

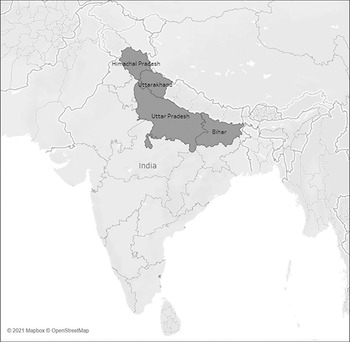

With these considerations in mind, I chose to investigate primary education in a small number of carefully selected states and rural locales in northern India. Existing studies have highlighted the differences between India’s “backward” northern Hindi belt and the more “progressive” southern states (Mehrotra Reference Mehrotra2006; Singh Reference Singh2016). However, meaningful variation exists within northern India, a region that has also seen important changes in recent decades. The four states selected for protracted investigation are HP, Uttarakhand, UP and Bihar (see map in Figure 1.1). These four states exhibit important similarities and differences on key demographic and socio-economic variables (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2). These states were selected to allow for rigorous theory testing through controlled comparisons, ensuring the internal validity of findings, while also permitting the construction of a general theory. Controlled comparisons are useful in qualitative, small-N research, permitting “intense theoretical engagement” with rival hypotheses to establish validity (Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013, 13). The states and local districts were chosen to probe my theory against alternative explanations for implementation.

Figure 1.1 Map of case study states in India

Table 1.1 Demographic indicators of case study states (2011)

Population (millions) | Annual population growth rate1 (%) | Rural population (%) | Population density (pop. per km2) | Scheduled Castes (%) | Scheduled Tribes (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Himachal Pradesh | 6.9 | 1.4 | 90.2 | 109 | 25.2 | 5.7 |

Uttarakhand | 10.1 | 1.8 | 69.8 | 159 | 18.8 | 2.9 |

Uttar Pradesh | 199.8 | 2.1 | 77.7 | 690 | 20.7 | 0.06 |

Bihar | 104.1 | 2.4 | 88.7 | 881 | 15.9 | 1.3 |

Note:

1. Population growth rate is the annualized average for 1991–2011.

Table 1.2 Socioeconomic indicators of case study states (1990–2011)

Income per capita1 (₹) | Annual income growth2 (%) | Poverty rate3 (%) | Literacy rate4 (%) | Sex ratio (females per 1,000 males) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Himachal Pradesh | 37,078 | 5.2 | 25.9 | 82.8 | 972 |

Uttarakhand | 32,934 | 5.7 | 27.4 | 78.9 | 963 |

Uttar Pradesh | 14,430 | 2.6 | 35.5 | 67.7 | 912 |

Bihar | 9,383 | 3.6 | 56.1 | 61.8 | 918 |

Note:

1. Income per capita is based on the Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) averaged over 2004–2010, at constant 2004–2005 prices.

2. Income growth is the annual growth rate of per capita NSDP for 1993–2010.

3. Poverty rate based on the Tendulkar Committee poverty estimation method, taken as the average rate over 1993–1994, 2004–2005 and 2009–2010.

4. Literacy rate and sex ratio are for the adult population.

Concentrating on these four states permits a close engagement with the politics and sociocultural context of northern India. Context is critical in the study of implementation (Grindle Reference Grindle1980). The same policies can stimulate very different political meanings and conflicts across settings, which raises the inescapable challenge of analytical equivalence in comparative politics. The risk of neglecting differences in political meaning is recognized in cross-national comparative research (Locke and Thelen Reference Locke and Thelen1995). However, subnational comparisons are not immune to these pitfalls, especially in a country as large and culturally heterogeneous as India. For example, while caste and gender discrimination has pervaded India’s education system, the nature of social norms and discrimination differs throughout the country (Drèze and Kingdon Reference Drèze and Kingdon2001). More generally, interdisciplinary research on governance and collective welfare suggests that local political dynamics and sociocultural practices influence how citizens participate in and experience public services (Rao and Walton Reference Rao and Walton2004; Hall and Lamont Reference Hall and Lamont2009). Attention to these contextual differences improves the descriptive accuracy of cases and validity of comparisons. Equally, it facilitates the identification of causal relationships. As Falleti and Lynch propose, “causation resides in the interaction between the mechanism and the context within which it operates” (2009, 1145).Footnote 22 My selection of north Indian states permits a close exploration of meanings and other contextual factors operating alongside causal mechanisms to shape implementation.

Ensuring that cases vary on outcomes of interest is a cardinal principal of case selection (Gerring Reference Gerring2004). The states of HP, Uttarakhand, UP and Bihar exhibit wide variation in outcomes for primary schooling, as the data presented in Chapter 2 will demonstrate. The selection of states and localities also presents theoretical conundrums for existing literature. Mountainous and landlocked, HP is one of India’s top-performing states in primary education. Uttarakhand exhibits markedly worse outcomes, despite having similar geographic, economic and sociocultural features to HP, as well as an historical lead in literacy. UP and Bihar are among India’s weakest performers in primary education. However, against theoretical expectations, UP has made considerable progress in the last two decades, improving access, enrollment and infrastructure, though the quality of services remains poor. More recently, Bihar too has recorded noteworthy gains in enrollment and infrastructure provision, but the quality of services lags considerably, despite political commitment to education from the state government.

To discern causal mechanisms for implementation, the research design controls for certain explanatory factors, including formal institutions and colonial administrative legacies. The four study states have common political, bureaucratic and constitutional-legal structures. Formal bureaucratic systems and procedures are the same, enabling the identification of differences in in formal bureaucratic norms. Government bureaucrats and schoolteachers are hired through common selection rules and have similar employment conditions, civil service protections, training and standards for pay and promotion. Officers in the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), the elite national civil service cadre, are recruited by competitive examination and assigned by lottery to states.Footnote 23 Once deployed, IAS officers work in the same state for most of their careers. Lower-level bureaucrats working in education and other social policy functions likewise get recruited by state-level public service commissions and do not move from their assigned states. However, bureaucrats can and do get transferred to different locations and administrative posts within their assigned states, sometimes for political reasons (Iyer and Mani Reference Iyer and Mani2011). These administrative conditions allow informal bureaucratic norms to vary and propagate differently across Indian states.

As with any inductive study, the research design must also confront difficulties of generalizability. To generalize over a country as large and diverse as India is a fraught enterprise. Guided by theory and political history, I chose cases that reflect important aspects of public administration in India. I began the study in UP, a state that could be the world’s seventh largest country, more populous than Brazil or Nigeria. The case of UP brings out the challenge of implementation on a large scale.Footnote 24 UP’s geography fluctuates from fertile Gangetic plains to drought-prone flatlands. Home to hundreds of castes, ethnolinguistic groups and a large Muslim population, UP is the political epicenter of the Hindi heartland. Its significance for national politics is unrivaled, having produced many prime ministers and national policymakers (Kudaisya Reference Kudaisya2002). Historically, UP adopted a “law and order” bureaucracy, once seen as a model for the rest of India (Kohli Reference Kohli1987). After a period of Congress Party dominance, UP state politics shifted to multiparty coalitions in the 1980s, a pattern followed by India’s central government. To use Gerring’s phrase, UP represents a “paradigm case” of legalistic bureaucracy in India, which can illuminate how legalism operates elsewhere in the country. It also constitutes a theoretically “least-likely case” for public service delivery. Explanations for implementation failure find their most favored terrain in UP. The colonial land revenue system in UP (zamindari) is associated with persistent inequality and the undersupply of public goods (Banerjee and Iyer 2005). UP is also the exemplar of Chandra’s (Reference Chandra2004) notion of “patronage democracy.” Caste politics in UP is seen to exacerbate social divisions and corruption (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey2002). If bureaucratic mechanisms are found to support implementation in UP, they have a strong chance of succeeding elsewhere. Within UP, I studied local districts (Saharanpur and Sitapur) in very different socioeconomic and cultural regions, helping to identify bureaucratic mechanisms operating across the state.

My arguments also leverage a matched-pair comparison of HP and Uttarakhand. These contiguous states in the Himalayan region were selected to hold several explanatory factors constant, such as geography, agrarian economy, social structure and party system. Less populous (by Indian standards), these states have income levels, poverty rates and other socioeconomic indicators that are comparable. The comparison of HP and Uttarakhand also controls for sociocultural norms, an important but understudied variable in public goods provision (Rao and Walton Reference Rao and Walton2004). The hill-based (Pahari) communities in the two states share similar customs, languages and religious practices, such as deity (devta) worship. Crucially, they have similar caste and gender norms, which may influence access to education. To ensure valid local-level comparisons, I selected administrative districts (Shimla in HP and Almora in Uttarakhand) with similar geographies, agrarian economies, caste structures and political party systems. Historically, both districts were directly governed by the British and were prime locations for military recruitment, which may have increased the demand for education (Eynde Reference Eynde2016). Following field visits and interviews with state officials, I selected three villages in each district for prolonged research. Village case selection accounted for population size, caste composition and distance from town centers and major roads.Footnote 25 A further innovation in my research design, I exploit the fact that, prior to becoming a separate state in 2000, Uttarakhand was part of UP for more than five decades after independence. Despite their very different economic and socio-demographic indicators, UP and Uttarakhand are bound by a shared political and administrative history. The political rupture caused by Uttarakhand’s separation presents a rare opportunity to test for whether and how bureaucratic norms persist and shape implementation within a new political environment. To strengthen the validity of local-level comparison, I studied districts on either side of the UP–Uttarakhand border (Saharanpur and Dehradun).

The multilevel comparative approach of this book demands this kind of rigorous attention to context. My main empirical findings suggest that bureaucratic norms persist and produce lasting effects on implementation, but I also investigate norm change through the analysis of institutional reforms in UP and the adjacent state of Bihar. Bihar’s human development performance ranks at the bottom among Indian states and the state long suffered from lawlessness, corruption and divisive caste politics. However, a political turnaround took place in the early 2000s, ushering in a period of relative stability that brought new state leadership committed to improving governance and public goods provision. I study the implementation of institutional reforms for education in Bihar alongside reforms undertaken in UP. In the late-1990s, the central government launched the Mahila Samakhya program in UP. Like the Bihar reforms, the Mahila Samakhya program sought to increase school participation among disadvantaged girls and improve the quality of services. The comparison of reform implementation in Bihar and UP allows me to hone in on mechanisms of bureaucratic norm change in the least likely settings.

1.6.3 Data and Methods

This book examines the state up close. The findings are based on intensive qualitative field research, combined with analysis of official documents, administrative data and archival sources. The qualitative data was collected during twenty-eight months of fieldwork between 2007 and 2011 and between 2013 and 2014. I employed multiple field methods to open up the “black box” of the bureaucracy and examine local state–society interactions. These methods included in-depth interviews and focus groups discussions (in Hindi) of various state and societal actors in education, participant observation with frontline officials and ethnographies conducted at the village and school level. The Appendix details my qualitative methods and gives a summary of local field sites and the sample of interview respondents. Each method had its advantages and limitations, but triangulation across methods helped substantiate the presence of bureaucratic norms and rule out alternative explanations, strengthening the overall findings (Denzin Reference Denzin2012). For instance, the weaving together of interviews with participant observation of frontline bureaucrats allowed me to probe discrepancies between “what they say” and “what they do” (Brodkin Reference Brodkin2008, 330). The inclusion of citizen perspectives on the state also presented an important check on the information given by bureaucrats.

I performed ethnographic fieldwork at multiple administrative levels, from subnational state capitals to administrative districts, and ultimately, village primary schools. In summary, I conducted 507 interviews of state actors (e.g. state and local bureaucrats, politicians and schoolteachers), 346 interviews with non-state actors (e.g., parents, village residents, unelected village leaders and civic agencies) and 103 focus group discussions with bureaucrats, teachers, parents and other village residents. Field research was supplemented by the systematic review of government documents (e.g. administrative reports and circulars), administrative data, media reports and a combination of primary and secondary historical sources. In all four states, I lived within or close to local field sites. My full-time presence in the field facilitated immersion into the social life of rural services, enabling a first-hand account of India’s bureaucracy and primary school system.

1.7 Plan of the Book

In seeking to explain subnational variation in the delivery of primary education in northern India, this book builds and tests a theory connecting differences in bureaucratic norms to varying patterns of implementation. The arguments are structured into three parts. Part 1 (Chapters 1–3) introduces the empirical puzzles and research design, theoretical arguments and institutional context for primary education in India. Chapter 2 presents my theoretical framework. I conceptualize policy implementation and introduce a measurement scheme that captures the variation in primary education outcomes in northern India. Next, I theorize bureaucratic norms and their influence on bureaucratic behavior. I develop the theoretical ideal types of legalistic and deliberative bureaucracy and delineate the causal mechanisms by which they produce differences in policy implementation. Moving up the causal chain, I theorize the political origins and propagation of bureaucratic norms, which I connect to historical processes of state-building. I then discuss my theory’s scope conditions and consider alternative political explanations for observed differences in implementation. Chapter 3 sets the empirical stage for the study, exploring the Indian state’s shifting involvement in primary education since independence, focusing on the recent period since economic liberalization. I examine the political currents behind the expansion of national education programming. I also introduce the formal administrative architecture for service provision, common across the four states that I studied, paving the way for an analysis of informal bureaucratic norms.

Part 2 (Chapters 4–7) presents the book’s main empirical findings. I explore the political origins of bureaucratic norms within each state as well as the contemporary context of implementation. Next, I present empirical materials from multilevel comparative field research to show how bureaucratic norms operate and affect the delivery of primary schooling. Through nested case studies, cutting across state-, district- and village-level administration, I show how bureaucratic norms influence the performance of different administrative tasks, while testing for alternative explanations. Chapter 4 begins by analyzing legalistic bureaucracy in the Gangetic plains of UP. I trace the origins of legalism back to the late-nineteenth century colonial ideal of a “law and order” state, later reinforced by governing elites competing for state control. I then show how legalistic bureaucracy has facilitated gains in school infrastructure and enrollment, while concurrently producing low quality services. Village-level case studies reveal that while legalistic processes of grievance redressal encourage societal participation they systematically burden marginalized citizens and reinforce social inequalities, weakening community oversight of primary schooling.

Chapters 5 and 6 examine implementation in the Himalayan region, leveraging a matched-pair comparison of HP and Uttarakhand. Chapter 5 connects HP’s improbable achievements in primary education to the establishment of a deliberative bureaucracy. I trace the origins of deliberation in HP to collective action by political and bureaucratic elites during the 1970s, spurred by the state’s political marginalization and acute need for central government fiscal support. Next, I show how deliberation unfolds inside state agencies and helps officials overcome a series of governance challenges, allowing them to adapt primary education to meet local needs. Village case studies demonstrate how deliberative bureaucracy helps sustain community monitoring of schools, leading to better quality services. Chapter 6 examines the comparative case of Uttarakhand, which has similar economic and sociocultural characteristics but performs significantly worse in delivering education. I show that, despite the political separation of Uttarakhand from UP in 2000, legalistic bureaucracy has persisted in Uttarakhand, producing a pattern of uneven implementation. Village case studies reveal that, while households voiced demands for better public services, their efforts were stymied by administrative burdens, inducing some to exit the government system and seek private schooling.

Chapter 7 revisits the Gangetic plains region to study the implementation of institutional reforms in UP and Bihar. In UP, I show how Mahila Samakhya, a central government program for women’s empowerment, promoted deliberation among frontline workers, who in turn mobilized village women’s associations to integrate disadvantaged girls into school. Fieldwork performed in three UP districts shows how deliberative bureaucracy manages social conflicts around girls’ education under conditions of entrenched social inequality. By contrast, Bihar’s institutional turnaround in the 2000s was initiated by the state’s political leadership, which was committed to improving governance and public services. I show how a broad institutional conversion to legalism took place within the bureaucracy, contributing to improved enrollments, school access and teacher recruitment. However, efforts to enhance the quality of education faltered, despite state commitment and sharing of “best practices” by education experts. I argue that frontline officials and schoolteachers experienced conflicts between the rules-based orientation of legalistic bureaucracy and the flexibility required to adopt new, innovative classroom teaching practices.

Part 3 examines the wider implications of the book for theory and policy. Chapter 8 situates the book’s arguments in a comparative perspective, examining cases beyond northern India. I explore a set of shadow cases, selected to cover a wide range of sociopolitical contexts: the south Indian state of Kerala, along with country-level cases of China, Finland and France. In Kerala, I show that deliberative bureaucracy has evolved alongside lower caste social movements, contributing to superior education outcomes within India. In the case of China, I explore how deliberative bureaucracy operates in a non-democratic environment, highlighting the adaptive and flexible models of bureaucratic governance that have shaped the delivery of education. Next, through a comparative assessment of school education in the advanced economies of Finland and France, I consider how divergent bureaucratic norms contribute to varying patterns of education service delivery, even in places with strong formal institutions. I conclude in Chapter 9 by examining the book’s contributions to scholarship and implications for policy. The argument connecting bureaucratic norms to policy implementation advances our understanding of institutions, social welfare and local state–society relations. For policy, I suggest how institutional reforms may help stimulate deliberation to improve the quality of public services and promote inclusive development.