Introduction

For many people, pregnancy and birth are positive and life-changing events. However, for some, the experience of birth can be traumatic, with around 4% of mothers developing PTSD (Yildiz et al., Reference Yildiz, Ayers and Phillips2017) and about 30% reporting subclinical symptoms (Creedy et al., Reference Creedy, Shochet and Horsfall2000). Prevalence rates of 0–8% have been reported in birthing partners (see Ayers et al., Reference Ayers, Wright and Wells2007; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Slade and Leviston2008; Iles et al., Reference Iles, Slade and Spiby2011; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare, Roberts, Alderdice, Coates, Hogg, Cheyne and Ayers2021). One recent study found 26% of the fathers and birthing partners interviewed reported symptoms consistent with diagnosable PTSD, although the authors recognised it was a self-selecting high-risk sample (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare, Roberts, Alderdice, Coates, Hogg, Cheyne and Ayers2021).

A range of experiences that can make pregnancy and birth traumatic are presented in Table 1. Notably, the level of medical intervention during birth is less strongly associated with post-partum PTSD (PP-PTSD) than the mother’s subjective experience (Dekel et al., Reference Dekel, Stuebe and Dishy2017). Indeed, perceived lack of support throughout the birth and negative interpretations of health care staffs’ behaviour are predictive of PTSD (Ayers et al., Reference Ayers, Bond, Bertullies and Wijma2016; Dikmen-Yildiz et al., Reference Dikmen-Yildiz, Ayers and Phillips2017; Harris and Ayers, Reference Harris and Ayers2012).

Table 1. Examples of experiences that can make pregnancy and birth traumatic

It is estimated that one in five pregnancies end in miscarriage and baby loss during pregnancy or birth (www.tommys.org). The loss of a baby is naturally a devastating experience for any parent. A normal grief reaction, which does not require intervention, would be expected. However, some parents may develop complications requiring treatment, such as prolonged grief disorder and/or PTSD following traumatic baby loss. PTSD is characterised by re-experiencing of the traumatic loss, whereas persistent yearning is the key feature of prolonged grief disorder. For information on differentiating between the two, see Duffy and Wild (Reference Duffy and Wild2023). A recent study found that 29% of women met criteria for PTSD one month following early pregnancy loss including miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, and 19% still met criteria after nine months (Farren et al., Reference Farren, Jalmbrant, Falconieri, Mictchell-Jones, Bobdiwala, Al-Memar, Tapp, Van Calster, Wynants, Timmerman and Bourne2020). People who have experienced baby loss can understandably find it challenging to pursue having another child. Those whose loss occurred earlier in pregnancy may be less likely to receive psychological therapy (Farren et al., Reference Farren, Jalmbrant, Falconieri, Mictchell-Jones, Bobdiwala, Al-Memar, Tapp, Van Calster, Wynants, Timmerman and Bourne2020).

PTSD after live childbirth can have a debilitating impact on parents already adapting to significant life changes (Brodrick and Williamson, Reference Brodrick and Williamson2020). The baby may be a reminder of the trauma, triggering re-experiencing of the worst moments (e.g. a mother fearing her baby would die). Avoidance of trauma reminders (such as talking about birth, medical appointments, etc.) can risk mother and baby not accessing necessary social and medical support. Hyperarousal symptoms (such as difficulty sleeping, concentrating, irritability, hypervigilance and exaggerated startle response) can make caring for a newborn even more challenging. Consequently, maternal PTSD has been found to be associated with co–morbid postnatal depression (White et al., Reference White, Matthey, Boyd and Barnett2006) as well as relationship problems (Iles et al., Reference Iles, Slade and Spiby2011) and may impact the decision about having another child (Beck, Reference Beck2004).

Some research has also found that birth-related PTSD is associated with negative consequences for the infant, such as low birth weight, lower rates of breast-feeding (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Ayers and Horsch2018), poorer social-emotional development (Garthus-Niegel et al., Reference Garthus-Niegel, Ayers, Martini, von Soest and Eberhard-Gran2017) and difficulties with mother–infant bonding (Suetsugu et al., Reference Suetsugu, Haruna and Kamibeppu2020). Early identification and treatment of PP–PTSD are therefore imperative to improve maternal health and potentially avert the longer-term consequences for both parents and child.

There is little published clinical guidance for treating PP-PTSD. In this paper, we address special considerations when treating people suffering with birth-related trauma or baby loss using cognitive therapy for PTSD (CT-PTSD; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). CT-PTSD has been shown to be highly acceptable and effective in adults with PTSD following a wide range of traumas in randomised controlled trials (e.g. Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus and Fennell2005; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Hackmann, Grey, Wild, Liness, Albert, Deale, Stott and Clark2014) and effectiveness studies conducted in routine clinical settings (e.g. Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Gillespie and Clark2007; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Grey, Wild, Stott, Liness, Deale, Handley, Albert, Cullen, Hackman, Manley, McManus, Brady, Salkovskis and Clark2013). CT-PTSD is recommended as a first-line intervention in NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018) and international PTSD guidelines (e.g. American Psychological Association, 2017; International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 2019). In this paper, we mainly focus on the mother as the patient and how we involve partners in therapy, if patients agree. We recognise that partners may also develop PTSD, but this is beyond the scope of this paper and as such will only be addressed briefly.

Ehlers and Clark’s cognitive model of PTSD

The central premise of cognitive therapy is that whilst people may face difficult times, it is the meaning they make of them that matters. Ehlers and Clark’s model (2000) suggests that PTSD develops when individuals process traumatic experiences in a way that produces a sense of a serious current threat. How individuals interpret their trauma and what has happened since and how the trauma memory is encoded and recalled gives rise to the sense of threat in the present. Cognitive and behavioural strategies people use to cope maintain the problem. Below we describe these core components of Ehlers and Clark’s (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000) cognitive model applied to PP-PTSD.

Personal meanings

Negative appraisals (personal meanings) of the trauma and/or its sequelae induce a sense of external or internal current threat. Perceived external threat can result from appraisals about impending danger (e.g. ‘I/my baby will die’) leading to excessive fear, or appraisals about perceived mistreatment by health care professionals or the unfairness of the trauma or its aftermath (e.g. ‘the midwives didn’t listen to me’) leading to persistent anger. Nebulous long-term worries about the baby may also result, e.g. ‘my baby has been damaged by the birth trauma in a way that will affect their life course’. Perceived internal threat often relates to negative appraisals of one’s behaviour, emotions or reactions during the trauma, and may lead to guilt (e.g. ‘I couldn’t get the baby out in time’; ‘my body is to blame’), or shame and low self-worth (e.g. ‘I should have been able to cope with the pain’; ‘I let my baby down because I did not hold him after he died’; ‘I’m a bad mum’; ‘I am weak’; ‘I failed’). Internal threats may also include negative interpretations of intrusions, e.g. ‘they mean I am going mad’; ‘if I think about the trauma, I won’t be able to cope’).

Poorly elaborated and disjointed memories

The worst moments of the trauma are poorly elaborated in memory which has the effect that the trauma is remembered in a disjointed way. When the worst moments are recalled, it may be difficult to access other information that the parent knows now that could update perceptions and negative appraisals at the time. For example, a mother recalls the moment her child stopped breathing and not the moments later when the baby was revived. Physiological factors common to birth and miscarriage, such as hormones, medication and sleep deprivation and the hospital environment, may mean processing during and after the traumatic childbirth is dominated by disjointed sensory impressions (data-driven processing), which influence how the memory is encoded and recalled. Due to poor integration, memories are re-experienced without context, as if they are happening right now rather than being a memory. They are also easily triggered by sensory cues with similarity to those occurring during trauma. Common examples of cues include beeping sounds similar to a hospital monitor, bodily positions similar to those during the birth, the smell of disinfectant, and physical sensations during sexual intercourse.

Maintaining cognitive and behavioural strategies

People naturally use a range of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope with their experience of perceived threat. The strategies they use depend on their appraisals. Commonly used strategies in PTSD such as ruminating about what happened, avoiding looking at or touching scars, or over-protecting a new baby can prevent change in problematic appraisals and trauma memories and thus keep the sense of current threat going. Other strategies can also directly increase symptoms, such as when trying hard to suppress memories of the trauma.

Cognitive therapy for PTSD (CT-PTSD)

Ehlers and Clark’s cognitive model of PTSD underpins the individual case formulation in CT-PTSD. An example is given in Fig. 1. In this case example, we see a range of personal meanings that drive the mother’s current sense of threat and are maintained by cognitive and behavioural strategies. For example, the theme of over-generalised sense of danger (‘my baby is going to die’) is maintained by safety behaviours including frequently checking whether the baby is breathing and avoiding other people looking after them. Themes of guilt and shame, e.g. ‘I’m an inadequate mother’ and ‘I’m to blame for not getting the baby out in time’, are maintained by rumination and self-criticism and avoidance of talking about the birth or meeting up with other new parents.

Figure 1. Example cognitive model of PTSD applied after birth trauma (Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). Round arrow heads denote ‘prevents change in’.

CT-PTSD is individually tailored to the case formulation and aims to:

-

(1) Modify threatening personal meanings of the trauma and its aftermath;

-

(2) Reduce re-experiencing by elaborating and updating trauma memories and enhancing discrimination between triggering stimuli in day-to-day life and the trauma memories (trigger discrimination);

-

(3) Addressing cognitive and behavioural strategies that maintain the person’s current sense of threat.

CT-PTSD for a small number of traumas is typically delivered across 12 weekly sessions of up to 90 minutes and up to three monthly booster sessions. Specific considerations when effectively delivering CT-PTSD for birth-related trauma are described below with clinical examples. The CT-PTSD interventions are described in greater detail in a therapist guide and a range of free-to-access training video demonstrations at www.oxcadatresources.com. Please also see Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Warnock-Parkes, Murray, Kerr, Thew, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2020) for a description of adaptions for remote delivery.

CT-PTSD following traumatic birth: clinical guidance

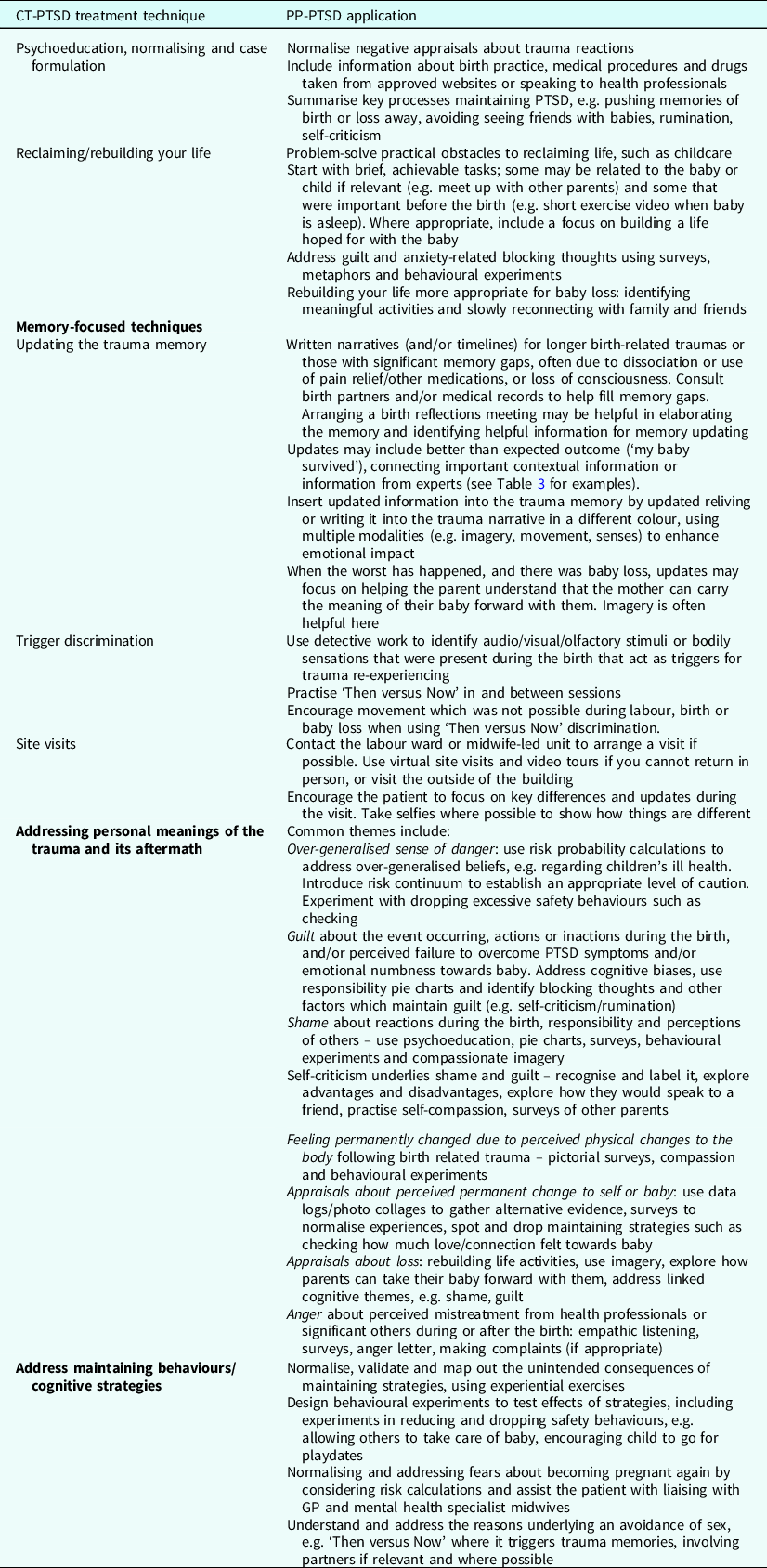

Below we outline clinical guidance for treating PTSD after a traumatic birth or baby loss using CT-PTSD. Table 2 provides a summary of the key interventions.

Table 2. An overview of CT-PTSD treatment strategies with PP-PTSD applications

Content warning: We have tried to keep upsetting details to a minimum, but some case examples are used to illustrate key techniques. We briefly cover therapist self-care towards the end of this paper.

Developing a trusting therapeutic relationship

A strong therapeutic relationship is an important foundation to CT-PTSD, particularly when highly personal and emotional details of traumatic events will be discussed. Many patients with PP-PTSD feel angry, let down and/or mistrustful towards health professionals if their prior experiences have been negative. Additionally, aspects of therapy, such as our physical environment if we work in a clinical space, can be triggering for some patients.

Acknowledging and validating these reactions is an important start. We can empathise with reports of prior mistreatment and commit to making this a more positive experience. It is important to show willingness to build trust over time within the therapeutic relationship, set this as a therapy task, discuss what would help and regularly seek feedback on whether/how this is progressing during treatment, adjusting our approach as needed. If our physical environment is triggering to a patient, we can offer to change aspects of it or provide treatment in a different format (e.g. remotely) at least short-term. We can also prioritise working on trigger discrimination strategies early in the treatment course (see later section). This can be important if our own therapist characteristics trigger trauma memories (e.g. the therapist reminds the patient of the midwife who she perceives mistreated her).

Psychoeducation, normalising and case formulation

CT-PTSD begins with psychoeducation and normalising information (see downloadable leaflet at www.oxcadatresources.com). PTSD symptoms are explained as understandable responses to trauma, which helps to address common negative interpretations of symptoms such as ‘feeling this way means I’m going crazy’; ‘if I feel numb or have flashbacks looking at my baby it means I do not love them’; ‘a good mother would feel more joy about their birth’. Information about drugs administered during labour can be helpful when normalising reactions. For example, a patient who believed they were a bad mother for having memory gaps of the birth found it helpful to know that the Pethidine (pain medication) they received often leads to memory gaps as it causes the person to drift in and out of consciousness. Patients can be referred to approved websites to gain further information including the NHS website (www.nhs.uk), Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (www.rcog.org.uk), Royal College of Midwives (www.rcm.org.uk) and charities such as Tommy’s (www.tommys.org). They might also find it helpful to speak to their GP, midwife or health visitor as another source of normalising and psychoeducation. Carrying out surveys of other people’s opinions can be helpful to provide information to update excessively negative appraisals. For example, a patient who believed ‘I’m a bad parent because my PTSD prevents me from feeling love all the time for my baby’ found it helpful to read a survey of other parents sharing they also had days and moments when they felt less loving towards their children. Please see Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Kerr, Warnock-Parkes, Grey, Clark and Ehlers2022) for detailed guidance on using surveys in CBT and our training video on using surveys in PTSD on www.oxcadatresources.com.

When developing the individual formulation (as shown in Fig. 1) with the patient, it is often broken down into smaller vicious cycles. Figure 2 gives an example of a mini cycle demonstrating the unintended consequence of pushing thoughts and memories away, leading to further re-experiencing. This was mapped out with a patient after carrying out the thought suppression experiment, whereby the patient is asked to purposefully not think about a green rabbit (or another striking image) to discover that this is impossible and results in an increase in related thoughts or images. Please see the video on Thought Suppression on www.oxcadatresources.com.

Figure 2. Example of brief formulation derived in session 1.

Reclaiming and rebuilding life activities

Reclaiming or rebuilding life activities is a core component of CT-PTSD. The aim is to encourage people from the first session and in every subsequent session to resume activities that they enjoyed and/or were meaningful to them before the trauma, or to try new activities in line with their therapy goals adjusting to changes in their life circumstances. A role play demonstration is available on www.oxcadatresources.com. Reclaiming your life starts with exploring what the patient enjoyed and valued before the trauma. It is important to be able to distinguish between activities avoided due to PTSD symptoms and those that have been naturally altered by the transition to parenthood, where this applies. If activities are no longer possible, alternatives that are pleasurable or give a similar sense of meaning are explored. Regarding PP-PTSD, it is also important to focus on building the life hoped for with a new baby, particularly where parents are currently avoiding spending time with their baby and have handed responsibility to significant others due to their PTSD symptoms. Identifying activities they want to work towards doing with their baby can be helpful, e.g. baby groups, meeting up with an antenatal group, playing with their baby, taking photos with their baby.

Addressing roadblocks to reclaiming life for new parents

Practical barriers

New parents can face practical challenges to reclaiming their life, e.g. accessing childcare and lack of social support, financial pressures, managing the exhaustion of caring for a young child, anxiety around leaving children, restrictions with ongoing pain or mobility difficulties, and changes in social interactions due to having a child or children with health problems or additional needs. A helpful first step can be to identify brief activities that are feasible for short time periods at home, perhaps when babies are sleeping. For example, spending just five minutes of daily time for themselves (e.g. reading a magazine article, making a cup of tea, having a shower, messaging a friend) is more achievable than striving for longer periods of time less frequently.

Addressing parental guilt and anxiety

Many parents report feeling guilty about being away from their baby or young children. They may also feel anxious about being separated from their child due to the heightened sense of risk present in PTSD. Identifying blocking thoughts to reclaiming life is key, e.g. ‘if I take time for myself, it means I don’t care about my baby’. Surveys can normalise such concerns and address unhelpful beliefs; for example, a survey of other parents asking how often they take time away from their children, how much anxiety this causes them and what the advantages might be of doing this. Involving partners where relevant can be helpful to both explore their beliefs and potential concerns too, and how they can support their partner both practically and emotionally. Metaphors can be useful: encouraging parents to reflect on flying safety instructions to put their oxygen masks on first before attending to their children’s or the importance of recharging themselves like a mobile phone, which is ineffective without charge. Encouraging patients to think about what they would say to a friend in the same situation can enable them to access a more compassionate stance. Problem-solving and/or involving partners, co-parents and wider family or friends can be beneficial where possible. If patients continue to feel anxious about leaving their baby/child, a behavioural experiment can help to test their feared predictions.

Addressing blocking beliefs linked to baby loss

When patients have lost a baby, this will naturally have a profound impact on their lives. Negative thoughts about the future are therefore understandable and should be validated with empathy. When beliefs such as ‘life is pointless if I cannot be a parent’ prevent rebuilding life, these can be gently addressed. As treatment progresses, sensitively exploring some of the qualities of being a parent that they long to have in their life and ways in which they can build this into their life can help.

For example, Samira longed to be a parent and to care for something in her life. She and her therapist explored ways in which she could start to get the feeling of giving care in small ways, including looking after her nephew and her dog.

Memory-focused techniques

Training videos on all the memory-focused techniques described below are available at www.oxcadatresources.com.

Updating trauma memories

Identifying and updating trauma-related meanings that maintain a current sense of threat to their own/their baby’s safety or view of themselves in the relevant parts of the trauma memory is a core component of CT-PTSD. There are three key stages of the updating trauma memories procedure for each hotspot. They are described below with considerations for birth trauma and baby loss.

Stage 1: Identify the most threatening personal meanings

The highly personal meanings of the trauma are difficult to access by just talking about it because of the disjointed nature of trauma memory recall and avoidance. Imaginal reliving (Foa and Rothbaum, Reference Foa and Rothbaum1998) and/or narrative writing (Resick and Schnicke, Reference Resick and Schnicke1993) are therefore used to access the worst moments in memory (the ‘hotspots’) and their most threatening meanings. In imaginal reliving, patients are guided to visualise what happened during the trauma moment-by-moment with eyes closed or averted while talking through their experience and engaging with the emotions they felt at the time. Narrative writing retains somewhat more distance from the trauma memory and less emotion. It is helpful for cases where traumas were prolonged (e.g. the mother was labouring for several days or required multiple interventions, or the baby was admitted to neonatal intensive care), the memory has significant gaps or is confused due to medication, exhaustion, or loss of consciousness during the trauma, or when the patient experienced significant dissociation during their trauma and/or during therapy sessions. Timelines may also be helpful for prolonged birth trauma or if appraisals linked to past trauma influenced appraisals of the birth experience. Hospital notes can help with constructing a narrative or timeline.

The aims of these procedures are to understand what happened and identify the most distressing moments (‘hotspots’) in the trauma memories and their personal meanings. Hotspots often have multiple meanings and may relate to the baby and/or the mother or partner (e.g. ‘my baby will die’, ‘my baby who died was not treated like a person’, ‘I will tear and be permanently changed’, ‘nobody is helping me – I’m not worthy of help’, ‘I should be able to help more’, etc.). Personal meanings can be influenced by previous experiences and beliefs including high standards and cultural expectations of birth (e.g. ‘if I cannot deliver my baby completely naturally, I’ve failed as a mother’, ‘all births should be natural and at home’, ‘hypnobirthing means no medication is necessary’).

It is important for patients to understand the rationale behind reliving in order to maximise engagement in this process. It can be helpful to involve partners in this stage of therapy where possible as partners may have beliefs about how best to manage the PTSD symptoms or the vulnerability of the patient that might undermine therapy unless identified and sensitively addressed. For example, the partner may think that reliving the trauma memory will re-traumatise the patient, making them worse, and they may therefore actively discourage memory work homework assignments.

Stage 2: Identify updating information that makes the worst moments less threatening

There might be relatively straightforward updates that can be identified by asking what the patient knows now, from the way the trauma unfolded or from reliable sources of information, including their (birthing) partner, who may be invited into early sessions with the patient’s agreement. It may be that the partner can provide information that helps to update negative meanings. These can then be brought into the memory (see Stage 3) as soon as possible (e.g. ‘I survived’; ‘my baby survived’). Therapist and patient can connect important contextual information from another time point of the pregnancy or birth to updates, e.g. a woman who believed she was ‘weak and a bad mum’ for not being able to push her baby out when the baby’s heart rate dropped, could be guided to bring in key updating information that she had been in labour for 36 hours and was exhausted. Where memory gaps exist, birth partners or doulas (if present) can be asked for information during joint sessions or for homework. The partner may have observed things that fill in distressing gaps in the patient’s memory or contradict a negative meaning.

Obtaining medical notes during birth reflection meetings can also help to address memory gaps, as well as identifying updating information to address key appraisals. Most hospitals offer the chance for parents to access a birth reflections, review or afterthoughts service which enables them to go through a timeline of their labour with a birth professional and ask questions about what happened. This can take time to arrange so it is worth enquiring about early in treatment. For example, a woman who believed she had been ignored by midwives and was unimportant when asking for an epidural discovered that the midwives had left the room to try to locate the anaesthetist.

Other appraisals need more detailed guided discovery to develop alternative perspectives, and a variety of techniques are drawn upon: including Socratic questioning, surveys and pie charts, behavioural experiments, imagery techniques, and positive data logs. Besides verbal discussion, creating experiential evidence for the new perspective is important, e.g. through surveys or behavioural experiments. Video feedback or photos can be a powerful tool to address appraisals about permanent physical change through pregnancy and birth.

When the worst-case scenario has occurred, for example a baby has died, it is important to sensitively elicit the worst meanings of the baby’s death. Some meanings driving understandable sadness and grief will require empathy and validation. Where appraisals are distorted, for example, parents blame themselves excessively or believe their baby is still suffering and stuck at that moment of the trauma, these can be gently addressed and updated. Imagery techniques (e.g. of baby looking calm, not suffering and at peace now) can be helpful to update these distressing hotspots (see below). See Wild et al. (Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023) for a detailed description of how to transform images of loss.

Stage 3: Link the updating information to the relevant moment in memory

The updating information generated in Stage 2 is linked with the respective hotspot (one at a time) to update the negative meanings and reduce re-experiencing. This can be done by asking the patient to recall and emotionally engage with the hotspot and hold it in mind while also reminding themselves of the updating information (e.g. ‘I thought my baby was in unimaginable pain, but I know now her level of brain development at birth meant she could not process pain in the same way as adults do; I know now that she is comfortable and happy, she is 8 months old and smiles and laughs every day’) or reading aloud the hotspot and the updating information (which has been written in another colour) within the narrative. Memories that are re-experienced are often multi-sensory. To make the updating information salient and convincing, it can help if updates are also multi-sensory. For example, if patients felt trapped (e.g. when temporarily paralysed with an epidural), moving about shows them that they are safe and no longer trapped. Other examples of updates in different sensory modalities include: looking at a photo or video of the baby smiling or crawling; using movement such as physically picking up the child or recalling how it felt to hold them after they were born; using smells, tastes or sounds that were different to those experienced at the time (e.g. smelling lavender if the patient re-experiences the hospital smell); and using soothing touch incompatible with discomfort or pain experienced at the time.

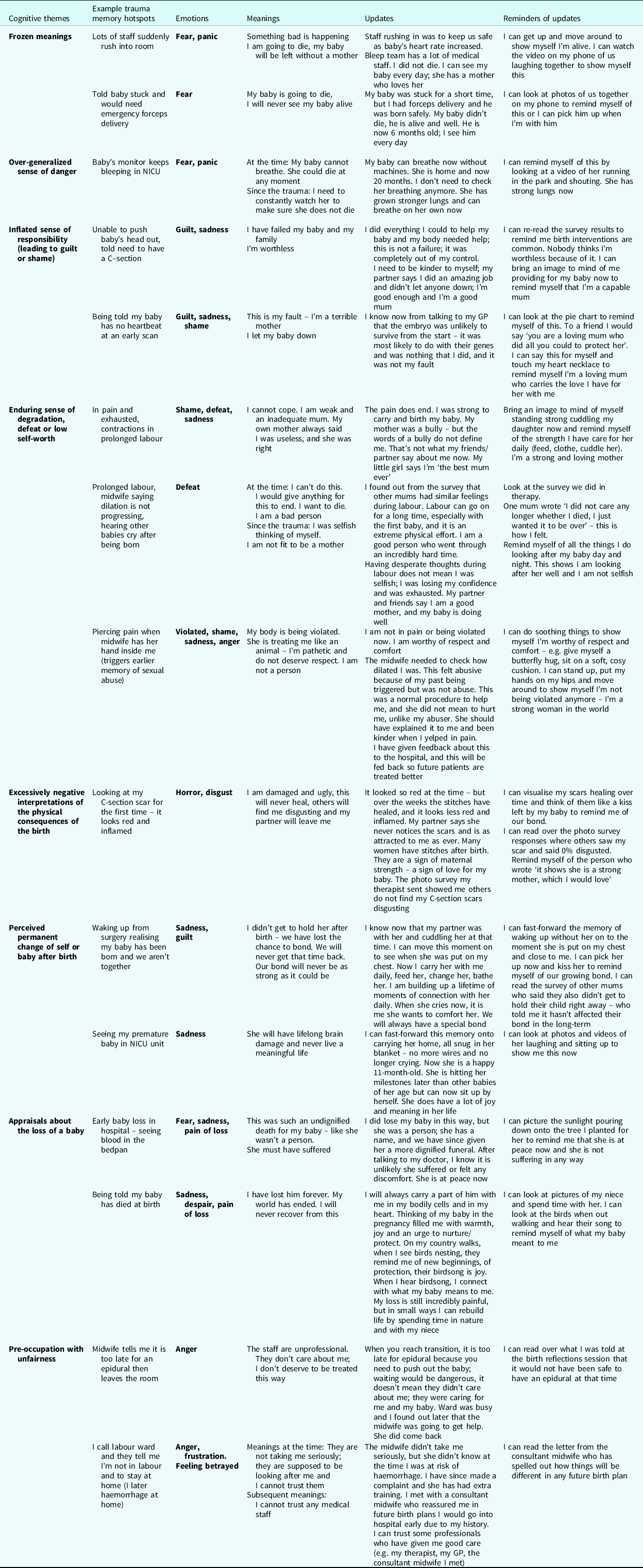

There is a video demonstration of the key steps in memory updating using a range of modalities with birth trauma available to view here (oxcadatresources.com). Patients are also encouraged to remind themselves of the updating information when they have intrusive memories and flashcards. Table 3 provides detailed examples of hotspots, potential updates, and reminders of these updates for birth-related trauma and baby loss.

Table 3. Illustrative case examples of cognitive themes addressed during memory updating in CT-PTSD for birth-related trauma and baby loss. Please note, one hot spot can have several of these meanings, each of which will need to be addressed

Involvement of partners in updating trauma memories

It is often helpful to involve partners or birthing partners, with the patient’s consent, to be able to explore their experience of the birth and sequalae. The partner may have observed things that fill in distressing gaps in the patient’s memory or contradict a negative meaning. This could be done either by a partner joining for a therapy session, or the patient and partner reading over the trauma narrative together for homework, elaborating it with any new information the partner has. For example, a woman who was unconscious in surgery during the birth of her child was distressed by an intrusive image she experienced when she came to of the baby left cold and alone after birth. She had never spoken to her partner about this but found it helpful to hear his account of what happened next: he had stayed with the baby, cuddling, and singing to him. She used this information to help update her hotspot in imagery.

Stimulus discrimination (‘Then versus Now’)

Another core part of memory work in CT-PTSD is stimulus (trigger) discrimination or ‘Then versus Now’. Patients are first helped to identify their memory triggers. These can be obvious triggers, e.g. seeing other pregnant women, seeing early photos of baby or the baby themselves, seeing health visitors or midwives, hearing about or watching birth-related TV programmes, or seeing scars. Anniversary reactions which are a common part of the experience of PTSD may make the child’s birthdays at best bittersweet and lead to significant avoidance.

There are also hidden or subtle memory triggers, which patients require more help to spot, as trauma memories often seem to come out of the blue. These include internal or external sensory triggers including visual patterns or colours, touch, smells, taste, sounds and internal body sensations. For example, sitting or lying positions, physical intimacy, similar colours to medical scrubs, seeing blood (e.g. during menstruation), seeing people wearing masks, people with a resemblance to those present at the birth, or other stimuli that were present in the hospital room, such as wall decorations like butterflies. They can also include interpersonal triggers, for example a therapist starting a therapy session slightly late triggered the memory of being left alone during labour for a patient. Therapists should keep in mind that aspects of therapy itself (as a healthcare treatment delivered by a professional) can be a trigger.

Once a trigger has been identified, patients are guided to use ‘Then versus Now’: first to identify what is similar between the stimulus in the traumatic situation then (e.g. beeping of heart rate monitor) and the trigger now (e.g. similar beeping of washing machine) and then on all the differences between the original situation and the trigger (and its context). It is best to first discuss this technique in session, drawing on a recent example. Patients will find that there are many more differences than similarities. It is important to include sensory differences in what patients can see, smell, touch, etc. now. The next step is to choose triggering stimuli to practise with in-session, such as looking at pictures of pregnant women. Patients are instructed to notice that a memory is triggered, what the trigger is, and then shift their attention to focus on all the differences between the trigger and current situation and the trauma, include sensory cues that make the differences salient, e.g. encourage patients to stand or move in a way that they could not move at the time or feeling their flat stomach with their hands. The final stage is to encourage patients to seek out memory triggers in their everyday life to practise discrimination, e.g. lying in a similar position, holding their baby in the same position as after birth, the smell of disinfectant, the sight of blood, having sex, spending time with pregnant people, or watching TV programmes, containing stories about birth or loss.

Partners are actively encouraged into sessions to facilitate their support for the patient using this technique. As before, it is important to address any concerns they may have in seeking out triggers to enable their full support for the patient. Patients may find flashcards helpful, reminding them of the differences before going into such situations. They are also encouraged to apply the technique when intrusive memories occur.

Where babies are still infants at the time of treatment, specificity is important with looking for differences between ‘Then versus Now’ (e.g. ‘she was newborn then and she is 5 months old now, she could not look at me or track movement then, but she can smile and look at me now). Bringing babies or children into session can be helpful to practise ‘Then versus Now’ together.

For parents who have lost a baby, it can help to bring memory updates in when faced with trauma triggers. For example, Billie, whose baby was lost at home in her bathroom, felt like her baby had not been treated like a person. She and her therapist practised ‘Then versus Now’ looking at different bathrooms. It helped her to remind herself of the differences (different toilet, different place, no longer losing her baby) but also to remind herself of her updated image – seeing her baby at peace in heaven, wrapped in blankets and being held by her grandmother, who had died two years prior.

Site visits

Returning to the site of the trauma is a key intervention in CT-PTSD. Site visits complete the trigger discrimination work and can help patients fully realise that the trauma is in the past, by focusing on all the differences between then (e.g. lots of blood on bed) and now (no blood on bed). See Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Merritt and Grey2015) for a detailed description of how to do site visits. Site visits can have the added benefit of helping elaborate the trauma memory, to discover new information to update key appraisals or to test out fearful expectations that patients may have, such as ‘if I go back to the unit again, I will have a flashback and get really upset’.

For patients whose early baby loss or birth was at home, we would still encourage site visits as patients can use subtle avoidance (e.g. not staying in certain rooms for long, avoiding looking at parts of a room, etc.), which blocks memories from being processed. When traumatic events took place in birthing centres or hospital, site visits need to be organised in advance and possibilities may be restricted at times. However, patients and therapists can contact specialist midwives to discuss possible options. Google Earth/Street View may be used for virtual site visits along with relevant hospital or birthing centre websites with pictures and videos if available. Even if the patient cannot return to the site, it may be possible to visit and walk to the outside of the labour ward while focusing on key differences and updates now (e.g. ‘the traumatic birth is in the past, it is not happening now’, ‘my baby is at peace now with my grandmother’, ‘I and my baby survived’, ‘my child is now 3 years old’), ideally taking a ‘selfie’ photo (perhaps including their baby/child if applicable) to show themselves that they survived and are safe now.

Where possible, therapists would accompany patients on the site visits or encourage patients to go accompanied by a partner, trusted family member or friend if this is not possible, involving this ‘co-therapist’ in the site visit planning session. Again, it is important to explore and address any concerns partners or other co-therapists have about the site visit in advance. When a trusted person accompanies the patient, it might be feasible for them to bring their child to the site visit, so that they can show themselves physically what has changed since the trauma. If this is not possible, bringing photos and videos of the child if they are alive and well now can be helpful to show the patient what they know now. If the patient’s child died at the site, patients might find it helpful to do something at the site to acknowledge their child and remind themselves of key updates. For example, one mother took an electric tealight with her to light at the site, signifying peace for her baby who she had feared had suffered when she died.

Working with meanings: common cognitive themes

As outlined above, addressing excessively negative personal meanings (appraisals) of the trauma and its aftermath is a central element of CT-PTSD. The Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin and Orsillo1999) and the discussion of the meanings of hotspots is useful in identifying relevant cognitive themes to address. As detailed above, therapist and patient identify and address the idiosyncratic meanings and explore the evidence. The therapist guides the patient to widen their perspective and consider alternative interpretations. The results of the discussion of meanings stemming from hotspots are used to update the trauma memory in Stage 3.

The patient’s unhelpful behaviours and cognitive strategies are closely linked to their appraisals (and can also help spot relevant appraisals) and therefore need to be addressed in parallel. It is important to normalise these as understandable attempts to cope with the perceived threat before looking at the costs and benefits of the strategies, which leads to the realisation that they may make the problem worse or prevent patients from finding out whether their appraisals are correct. Behavioural experiments testing appraisals involve dropping the unhelpful safety behaviours to find out what happens. Patients are reminded to use the ‘Then versus Now’ discrimination during behavioural experiments to prevent intrusions from the trauma overshadowing current reality. Cognitive strategies such as rumination and self-criticism are often prominent after birth-related trauma or baby loss and maintain appraisals. Helping patients to spot, label and disengage from rumination that is often self-critical in nature can be useful early in treatment as if not addressed this can interfere with memory updating. Below we outline how to address common cognitive themes.

Addressing over-generalised appraisals about danger

Following a traumatic birth or baby loss, patients may develop an over-generalised sense of danger that can take several forms. They may excessively worry about their baby dying and become hypervigilant for signs of distress. They may also believe their other children are at greater risk and take excessive precautions (safety behaviours) or avoid certain activities or places to keep them safe. They may believe that health professionals cannot be trusted and avoid postnatal appointments and other medical care. Patients may also believe they will have another traumatic birth or baby loss if they get pregnant again and avoid sex and physical intimacy. Patients who become pregnant again after birth trauma or baby loss may believe that history will repeat itself and may be highly anxious about the pregnancy and forthcoming birth. In therapy, therapist and patient collaboratively consider an alternative hypothesis: that their intrusive trauma memories lead to a heightened sense of risk and an over-estimation of danger, and that some of the strategies they use to stay safe increases their anxiety and sense of risk.

Experiential exercises demonstrating the impact of maintaining strategies

Collaboratively mapping out the unintended consequences of hypervigilance and/or safety behaviours in a mini vicious cycle and using experiential exercises to demonstrate their effects can be helpful to guide patients to consider that the risk they perceive may be exaggerated.

Case example: Aida’s daughter stopped breathing after birth and needed urgent intervention. Aida believed that she had to be extra vigilant to keep her daughter safe. She checked on her daughter frequently, scanning for signs of breathing difficulties, particularly if she was unwell and she never let other people look after her. Aida had never considered the unintended consequences of these strategies before, but her therapist encouraged her to discover that this increased her anxiety and impacted her enjoyment of parenthood. During a remote therapy call, Aida’s therapist encouraged her to make a cup of tea in her kitchen while focusing on the task at hand for two minutes and rate her anxiety and perceived level of threat on a 0–100 scale. The therapist then encouraged Aida to switch to scanning the kitchen for signs of danger (e.g. sharp objects, sources of heat that could cause injury) for two minutes and repeated the ratings. Aida was able to discover that by simply scanning for danger, her anxiety and threat levels significantly increased. Aida’s therapist asked her: ‘what does this tell you about the possible impact of scanning for signs that your daughter is struggling to breathe?’.

Continuum of risk

As young children do require close monitoring and care, it can be difficult for parents to know whether their strategies are reasonable or excessive. Surveys and asking friends can be helpful to ascertain, e.g. how much other parents check on their children in the night or leave them with trusted others to care for them. Mapping on a continuum where other parents are, where the patient is and where they would like to be is beneficial, as the goal of therapy is not to remove appropriate levels of monitoring but to help the parent engage in a more helpful level of checking. For babies or children who have additional health complications following birth, medical advice can be useful to ascertain what level of monitoring is appropriate versus excessive.

Risk calculations

Risk calculations can help patients discover that their feelings of danger are coming from the trauma memory. They are helpful when patients fear ongoing danger to their children.

For example, after Bruce’s son was taken to NICU after birth, he became concerned that his son would be seriously harmed in an accident and end up in hospital again if he went outside of the house. His son was now three years old. Bruce and his therapist calculated that his son had left the house most days since he was born (roughly 1000 days) but had only once been hospitalised once after birth (1/1000 = 0.0001). This helped Bruce see that, although he felt like his son was in 80% danger daily of being seriously harmed, the probability was much lower.

Some parents develop beliefs that their child is particularly vulnerable to common childhood illnesses after a traumatic birth. Here, surveys can help normalise that childhood colds and viruses are common.

Bruce believed that his son’s stay in NICU meant he was more likely to get ill again in the future. He benefited from speaking to his GP who was able to provide medical information to reassure him that his son did not require additional monitoring over and above other children.

Behavioural experiments

Behavioural experiments help patients discover that their sense of danger is coming from the trauma memory. It is important for patients to use trigger discrimination in case intrusive memories or other re-experiencing symptoms are triggered during the experiment.

Aida asked her mother to look after her daughter for two hours while dropping the safety behaviour of repeatedly calling to check on her. She discovered that, even though she believed 70% her daughter would stop breathing, she was fine and enjoyed spending time with her granny. Aida was able to see that her sense of danger was coming from the trauma memory; her daughter was much safer than she had predicted. Similarly, Bruce tried taking his son to the park and focusing on playing with him rather than scanning the park for signs of danger. He discovered that he and his son enjoyed the time more than they usually did and his son did not have an accident as he had predicted.

Fears about getting pregnant or giving birth again

Many patients who have experienced a traumatic birth or baby loss feel anxious about experiencing another pregnancy and going through a similar experience. Future pregnancies should therefore ideally be included as part of the therapy ‘blueprint’ or relapse plan. Specific fears about giving birth can be addressed using cognitive techniques such as risk probabilities. Therapists should encourage their patients (if already pregnant) to speak to their maternity team about their concerns and seek a referral to a mental health specialist midwife. They should be able to answer questions, e.g. about the probability of a similar type of birth or complication occurring again, and assist with preparing a detailed birth plan that takes their needs into account. The therapist can assist by liaising with the maternity team, accompanying the patient to the maternity unit as part of birth preparation, and discussing specific strategies that might be helpful, such as the use of ‘Then versus Now’ during labour to help manage any re-experiencing symptoms. Preparing a ‘Then versus Now kit’ to take to subsequent births can help (e.g. a flashcard with key differences written on it alongside objects that were not present at the traumatic birth, such as essential oils, a recent photo, etc.).

Working with an inflated sense of responsibility

Guilt stems from an inflated sense of responsibility and/or excessive self-blame. It can be about the event occurring in and of itself, actions or failure to act during the birth or baby loss, and/or perceived failure to overcome symptoms. Guilt can be related to particular hotspots in the trauma (‘this is my fault, I could have prevented my baby’s distress’, ‘having sex caused me to miscarry’) or post-trauma appraisals (‘if only I had gone to hospital sooner’), which often links to rumination. Guilt can also be linked with shame (e.g. ‘I should have known my baby was in distress – I’m such a terrible mother’). A range of cognitive biases operate to maintain guilt and require cognitive restructuring, including hindsight bias (judging decisions based on what parents know afterwards/now rather than what they knew at the time), discounting other factors involved (e.g. examinations had all been normal, no indication of any problems, checking with midwives that sex was possible during pregnancy), minimising their own experience or pain (e.g. disregarding 36 hours of labour and intense pain), discounting positive actions (e.g. telling midwife something didn’t feel right, asking to see a doctor), superhuman standards (e.g. ‘I should have known my baby was in distress and come to hospital sooner’) and emotional reasoning (e.g. feeling guilty being taken as being guilty).

Pie charts are helpful to acknowledge other factors that contributed to a birth trauma or baby loss. For example, challenging an appraisal like ‘it was all my fault – I should have come into hospital sooner’ by considering who else was there and who the patient had spoken to, e.g. her partner, her mother, GP and the midwife on the phone who recommended staying at home for longer.

Seeking health information or expert advice can be helpful to correct assumptions patients may hold that might drive their inflated sense of responsibility. For example, a patient who believed she was to blame for her miscarriage because she exercised during pregnancy found it helpful to discover that miscarriages can be common and not linked to exercise.

Timelines can be used to challenge hindsight bias; for example, marking when the patient knew various information, e.g. the baby only showed signs of distress at the end of the labouring stage when the patient passed meconium, no other signs of baby’s distress were apparent until that time.

Surveys can be helpful to challenge superhuman standards, e.g. how could anyone know their baby was in distress if there were no signs to the mother or anyone else?

Addressing blocking thoughts that might maintain guilt is also key, e.g. ‘if I don’t feel guilty, then it would show I don’t care about my baby’ and consider doing a cost–benefits analysis for holding onto this belief, before moving onto considering alternative beliefs. It can help to know the views of the patient’s (birthing) partner if they have one, or wider family. If significant others are blaming and critical this may need addressing, e.g. inviting a loved one to join a session. See Young et al. (Reference Young, Chessell, Chisholm, Brady, Akbar, Vann, Rouf and Dixon2021) for a comprehensive guide for working with trauma-related guilt.

Behaviours and cognitive strategies that maintain guilt. Much like in shame, people who feel guilty often ruminate about the trauma (e.g. dwelling on ‘should’ thoughts such as ‘I should have gone to the hospital sooner’), engage in harsh self-criticism, and withdraw from others. Similar strategies as those outlined above can be helpful.

For example, Jane believed she was to blame for her miscarriage because she had sex with her partner the previous evening. She believed she did not deserve to have pleasure or happiness in her life and so had stopped doing anything she enjoyed. Her therapist encouraged her to experiment with reclaiming her life and living as if she was not to blame by seeing friends again and talking about the trauma. This behavioural experiment helped her learn that her friends did not agree that she was to blame for what had happened and instead encouraged her to be kind to herself.

Working with an enduring sense of shame/degradation, defeat or low-self worth

Patients can feel ashamed about a range of experiences during or following a traumatic birth or baby loss. They may have shame-related misinterpretations about their own reactions that violate their internal standards (e.g. ‘my body let me down’, ‘I failed because I didn’t have a “natural” birth’, ‘I’m weak, I should have been able to do it without the drugs’, ‘I’m weird/disgusting because my bowels opened while giving birth’, ‘I’m a bad person for shouting and swearing at the midwife’); their sense of responsibility for the trauma, which link to cognitions around guilt (e.g. ‘I should have come in earlier’, ‘I should have known my baby was in trouble’); and fears around how others will perceive the trauma or their reactions to it (e.g. ‘others will think I’m weak’, ‘they will think I don’t love my baby if they find out I have PTSD’). Shame can also stem from appraisals of physical changes since the pregnancy of birth (e.g. ‘my body looks disgusting because I gained so much weight’, ‘people will notice my scar and think it’s hideous’).

Strong feelings of degradation and low self-worth may be more common for people who had an earlier trauma history and/or pre-existing low self-esteem beliefs which are triggered during the birth. A traumatic birth or loss of a baby may then seem to confirm and strengthen earlier beliefs, e.g. ‘this happened because I always cause bad things to happen’. A common example might be a patient who felt unloved as a child experiencing busy medical staff as uncaring, leading to shame-based appraisals, e.g. ‘I wasn’t listened to by my midwives because I am unworthy of love/care’.

Prolonged labours can lead to a sense of mental defeat, whereby people feel as if they are no longer a person and cut off from their own body. This feeling may be re-experienced when memories are triggered and lead to secondary appraisals such as ‘my body no longer feels like my own’. People may also be self-critical about having experienced mental defeat (e.g. ‘I’m pathetic for having “given up”, others would have been stronger’).

A warm and empathic, non-judgemental therapy relationship is crucial where people are experiencing shame and low self-worth. Therapists need to also be mindful of how shame can prevent patients being open and honest in session and the importance of early normalising and psychoeducation.

Pie charts can be useful to help patients consider other factors involved where they are inappropriately feeling responsible for particular aspects of the trauma.

Surveys are a key intervention to help challenge specific distorted appraisals and often form a useful first step in reducing avoidance and talking to trusted friends or family about their appraisals. Within surveys, having a compassionate question asking how they would respond to a friend in the same situation based on a vignette is particularly helpful, as is asking the patient to complete the survey themselves. An example survey is given in Fig. 3 for Greta. Reclaiming/rebuilding life assignments are also important, e.g. those that give patients the experience of being accepted by others (e.g. go for coffee with other mums, speak to other parents).

Figure 3. Example of a survey.

The survey helped Greta discover to her surprise that none of the 12 respondents saw her as a failure or weak for having a C-section. The compassionate normalising responses to the free text items (particularly the final question) helped to shift her negative self-beliefs and were added to her memory updates. It also helped Greta to realise how much her own responses differed from the responses of others and the extent of her self-criticism.

Using imagery. Imagery techniques can be helpful in updating shame-based hotspots. For example, Kath was ashamed that she was in so much pain she could not push her baby out and needed a C-section after the baby’s heart rate spiked. She pictured herself curled up on the hospital bed in the foetal position looking weak. During updating, she found it helpful to bring an image of herself to mind standing tall with a Wonder Woman cape on, holding her baby after he was born. This reminded her that although she felt weak, she had been strong enough to carry him for 9 months and birth him after a prolonged labour.

Addressing cognitive and maintaining strategies that maintain shame-based appraisals. Social withdrawal is common when people feel shame, which can maintain shame appraisals and interfere with accessing support when needed as a new parent. Following the discussion of the survey, patients can be encouraged to conduct behavioural experiments telling friends or family about their experiences and concerns, asking what they think and observing how they respond.

For example, Jessie had been too ashamed to tell other new parents that she had not held her baby when he was born as she felt too unwell and shaky. She experimented with telling a good friend about this and was surprised to discover they had a similar experience themselves and did not respond in the negative way she expected.

Rumination and self-criticism often perpetuate shame . Training videos on the interventions (e.g. exploring the advantages and disadvantages of these processes, noticing, labelling, and disengaging from rumination) are available from www.oxcadatresources.com. For those patients who ruminate in a highly self-critical way, it can help to ask them what they would say to a friend in the same situation, or to think about the nurturing way they would speak to their own children and then try to speak to themselves in the same kind way. See Cree (Reference Cree2010, Reference Cree2015) for further guidance on developing self-compassion with mothers. Finally, writing a compassionate letter to themselves can be helpful (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010).

Addressing longstanding low self-worth. Patients who already had low self-esteem or who develop enduring beliefs linked to low self-worth may benefit from cognitive strategies such as continuum methods and positive data logs (see Padesky, Reference Padesky1994) and techniques to target the ‘inner critic’. Videos on these techniques are available on www.oxcadatresources.com. Occasionally, earlier memories provide strong emotional evidence for a belief.

For example, Kath had experienced emotional abuse from her mother as a child. When she remembered the birth, she remembered her mother telling her that she was pathetic when she cried as a child, and this memory made her feel even worse. As well as updating her trauma memory with her Wonder Woman image, Kath “travelled back in time” in imagery and told her younger self that she was not pathetic for crying when she was in pain.

Updating mental defeat hotspots. If patients experienced mental defeat during the trauma, it can be helpful to provide some psychoeducation to normalise the experience, by explaining that this is a common reaction to prolonged and inescapable suffering, and does not mean that the person is weak. Updates relating to this as a temporary experience (‘I felt defeated and inhuman then, which is a normal response to such a long labour, but now I know that I am a strong person’), can be strengthened with physical movement and other forms of evidence.

Working with excessively negative interpretations of the physical consequences of the birth

Many women feel self-conscious of the changes to their bodies resulting from childbirth. Such changes can result from interventions, e.g. episiotomy, forceps or ventose delivery or C–section, or other more general changes, e.g. changes in the appearance and feel of the vagina, abdomen or breasts. Surveys, including pictorial ones, are helpful to normalise changes in appearance after birth. Sometimes therapists can also access normalising information online.

For example, Sadie believed her vulva looked ugly and unattractive after an episiotomy, but her therapist recommended she look at the Great Wall of Vagina online (www.thegreatwallofvulva.com), a sculpture of 400 vulvas, made by Jamie McCartney which she found highly normalising.

Bringing in compassion is also key: asking the patient what they would say to a friend if they had the same concern.

Some women re-experience traumatic images of their body or scars from the birth or the aftermath. Updating these memories in imagery to show how they have healed can be powerful. For example, Sadie visualised her episiotomy scar as red, puffy and infected as it was just after birth. During treatment she updated this image – visualising it healing over time, like a time-lapse.

Addressing cognitive and maintaining strategies that maintain appraisals about physical appearance. Some patients find themselves pre-occupied with their appearance and avoid intimacy or looking at themselves in the mirror and tend to engage in rumination. They may also use safety behaviours, such as wearing particular clothes to hide their body or avoid looking at or touching scars.

For example, Kerry had never touched her C-section scar as it triggered trauma memories. She believed it was a sign her body was weak and disgusting. During treatment she was encouraged to start by looking at her scar while using ‘Then versus Now’ and to work up to massaging oil into her scar that was recommended by her midwife. In doing this, Kerry was able to see that her scar had healed since the birth. Using the oil helped her recovery further. This was a key step in facilitating Kerry’s change in appraisal to seeing her scar as a kiss from her baby and a sign of her body’s strength.

Behavioural experiments are key when addressing appraisals about physical change. For example, Sadie reported that she wanted to be more intimate with her wife but believed her vulva was ugly and she would not want to have sex with her. As a behavioural experiment, Sadie asked her wife for her opinion and found that she was highly supportive, adding that this was not something she had noticed or cared about.

Resuming sexual intimacy . Patients commonly avoid sex following birth-related or baby loss trauma for a variety of reasons: it can trigger trauma memories, fear of becoming pregnant again, fear of pain, self-consciousness about body changes, or because they feel distant or detached from their partner. This can become a source of strain on the relationship and resuming sexual intimacy may therefore be a goal for therapy. It can be helpful to agree a temporary ‘ban’ on sex to remove pressure and encourage a couple to focus on increasing physical intimacy (e.g. holding hands, hugs, massage) without the expectation that it will lead to sex. The patient can practise ‘Then versus Now’ to break the link between the trauma memory and sexual triggers. For example, if laying down in bed is part of the trigger, then the patient could start with practising ‘Then versus Now’ while laying down outside of sexual intimacy. Involving partners in this process can be helpful. For example, a woman found that her partner kissing her was a trigger to the moment a mask was placed over her mouth during birth and she lost consciousness. During a session, the therapist explained trauma triggers and ‘Then versus Now’ to them both. They then practised together using ‘Then versus Now’, starting with her partner gently putting his hand on her face during the session, moving onto kissing using ‘Then versus Now’ for homework. Intentionally making things as different as possible during intimacy so that there are more differences to focus on can help. For example, starting with being in positions different from those during labour.

It may be that it is the patient’s partner who is avoidant of post-trauma physical contact, perhaps due to fear of triggering memories or of the patient becoming pregnant again, or fear of their vulnerability. This avoidance can lead to patients feeling unloved and/or unattractive and again lead to relationship difficulties. In this situation, it can be helpful to invite partners into sessions to explore their concerns and beliefs with the patient and how to address these.

Working with perceived permanent change of self or baby after birth

In addition to concerns about the physical consequences of the birth on the mother, some parents also have negative appraisals about themselves, or their baby, being permanently changed in other ways. For example, after an exhausting labour a mother did not feel the rush of love she expected and feared she would never bond with her child. Another parent feared that due to the baby’s time in NICU they would have lifelong brain damage and never live a meaningful life. A father worried that because he had PTSD, he would never be a good parent.

In addition to some of the strategies outlined above (e.g. getting expert opinions, surveys of other parents who had similar experiences), we have found sharing some normalising information can help. For example, some patients have found it helpful to hear that in one study, 40% of first-time mothers reported feeling indifferent when meeting their newborn (Robson and Kumar, Reference Robson and Kumar1980). It can help to gather alternative evidence over the course of a week or two. For example, a mother who feared she would never have a strong bond with her child puts together a collage of photos of the two of them cuddling and connecting that can then be used in memory updating.

Addressing cognitive and maintaining strategies that maintain permanent change appraisals. These appraisals are often maintained by cognitive strategies that will need addressing, such as rumination and self-criticism. Checking behaviours can be common, such as the parent repeatedly checking how connected they feel to their child or if they are reaching their milestones. These will need to be identified and dropped. For example, a mother is encouraged to experiment for a few minutes with playing with her baby while repeatedly checking how connected and bonded she feels, and then dropping this strategy and instead focusing on being more in the moment with playing with her son. She is surprised to discover that when she stops checking and focuses more on playing with him, she feels less anxious and more connected to her son. Once safety behaviours that fuel difficulties with bonding are dropped (e.g. overprotection of infant or avoidance of infant interaction) we tend to find that bonding between parent and child deepens. In occasions where difficulties persist, more specialist parent–infant interventions could be considered.

Working with appraisals about the loss of a baby

It is important for patients who have experienced a loss time to talk about their bereavement. While the worst has happened, there are often key appraisals related to loss that drive distress and sense of nowness, leaving the person feeling as though their child is not at peace. For example, ‘my baby suffered when they died’, ‘they were not treated like a person’, ‘my baby’s death was horrific and undignified’. Care should be taken to explore these meanings that can be sensitively updated. Imagery is helpful, often earlier in therapy, prior to reliving.

For example, when Samira’s baby was in NICU he had tears running down his face just before he died. For Samira, the worst meaning was that her baby was in pain and was still suffering. In therapy she visualised where she would like to see him now, at peace and no longer suffering. She brought this image into her memory to show herself he was resting at peace now.

Losses may be experienced even when the baby has survived. The baby may have disabilities and there may be grieving for the child the parents perceive they have lost. Alternatively, as time goes by it may be clearer to the parents that developmental milestones are not being met. This may further activate beliefs linked with guilt and shame. It is possible that the PTSD symptoms only become significantly distressing and interfering at such a later time when the perceived level of threat rises. Delayed-onset PTSD may be more confusing or concerning to parents. Normalising, and more fully understanding what leads to the increased sense of threat, such as for example the realisation of further losses, will be helpful. The other techniques described above will also be used, e.g. if patients feel they are to blame for the loss or are ashamed about how they reacted.

Taking the baby with you

When parents are struggling with the loss of a child, it can help to think about how they can take the baby forward with them through imagery, a personal value, behaviour or activity (see Wild et al., Reference Wild, Duffy and Ehlers2023). Samira described her pregnancy as her ‘ray of sunshine’. She visualised a ray of light falling on her as a way to show her that her baby will always be with her, that she carries him forward in her life. After baby loss, some patients find it comforting to discover that foetal cells transfer during pregnancy and can remain within the mother (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Nelson, Gadi and Gammill2013). After Jenny’s stillbirth she found comfort in reminding herself ‘I will always carry a part of her inside my body, she will be with me always’.

Rebuilding life and addressing other maintaining strategies

Many of the strategies already covered (rumination, self-criticism and social withdrawal) are common after a loss. Many parents report finding it upsetting that others do not ask them about their loss and may take this personally, leading them to avoid contact (e.g. ‘they do not care about the baby or me’). Surveys here can help make sense of why other people find baby loss hard to discuss (reasons often include not wanting to upset the parent or not knowing what to say). Experiments may involve reaching out to others and asking for support. Others may avoid social situations for a range of reasons, such as feeling upset when they see other families with children, fearing people will ask about the baby if they do not know about the loss, feeling disconnected from others or believing that they will not enjoy themselves. Other interventions such as practising trigger discrimination, role-playing difficult conversations and behavioural experiments may also be helpful.

Working with pre-occupation with unfairness

Patients can feel angry in response to a range of experiences in which there has been unfairness or injustice, legal or moral rules have been broken, or they feel betrayed in some way. During birth-related trauma or baby loss, it may be that patients felt ignored, overlooked, dismissed, criticised, or mistreated by their birthing partner or healthcare professionals, or that professionals were perceived to break the rules. Patients can also feel angry about the aftermath of the trauma, e.g. physical problems because of the delivery or being given little time with their stillborn baby after birth. It is important to ask patients whether they think they were mistreated or discriminated against in any way because of their personal characteristics, such as their race, sexual orientation or gender identity, age, faith or religion, beliefs or disability. This is particularly important considering data indicating racial inequality in perinatal care (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Bunch, Patel, Shakespeare, Kotnis, Kenyon and Kurinczuk2022). Patients may find experiences of racism or other prejudice particularly hard to disclose if the therapist appears to have a different cultural background. It is important to sensitively explore the patient’s experience once a trusting therapy relationship has been established.

Providing empathy

It is important for therapists to make it clear that they are on the patient’s side; they understand why the patient feels angry and agree with them where it is not excessive or distorted. This is especially important as therapists may act as a trigger for patients, as health professionals.

Cognitive restructuring

Sometimes anger-related appraisals represent misunderstandings or distortions which can be sensitively addressed. For example, patients may have felt angry because they believed they were being ignored but may realise with hindsight that staff were stretched and under-resourced and were not deliberately ignoring them. Where anger relates to genuine mistreatment or malpractice, the therapist can support the patient to raise a complaint if desired or facilitate communication with the maternity unit to raise and hopefully resolve concerns.

Letting go of anger

It can also be helpful to focus on cost–benefits analyses of holding onto anger, including asking: who does it help?; do the professionals involved know they are still angry?; how much time does it take up?; and what does it prevent them from doing? Anger letters, which are not usually sent, can be invaluable to help patients express their feelings and thoughts to people involved in their treatment (see Fig. 4 for an example). Notably, patients may feel angry and resentful towards birthing partners, e.g. ‘they didn’t stick up for me, they didn’t advocate for me enough’ as well as the government in the case of birthing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g. ‘my partner should have been allowed to be there with me, I had to do this all by myself’.

Figure 4. Example anger letter.

Addressing rumination and other behaviours that maintain anger

Rumination can be addressed as described earlier. Many people who feel angry about the way they were treated during the trauma may also avoid contact with future professionals, which maintains their anger. For example, Patricia was angry with the way the health care professionals seemed to dismiss her during her early baby loss. She believed ‘medical staff are rubbish and uncaring’. She had since avoided all healthcare appointments, which maintained her belief. In therapy, she experimented with booking a GP appointment to discuss her future fertility. She was surprised to discover that her GP was helpful, learning that not all healthcare professionals would be dismissive.

Therapists should look out for blocking thoughts that might keep people stuck with anger. For example, Patricia thought ‘If I let go of my anger, it means I no longer care about my baby who was lost’. Patricia’s therapist helped her to identify a more positive channel to honour her baby, by getting involved with a miscarriage charity and planting a memorial tree.

Additional considerations

Order of interventions

We have described CT-PTSD techniques in a linear fashion. However, work on trauma memories, appraisals and the behavioural and cognitive coping strategies that follow from them are usually closely intertwined. For example, the updating memory procedure closely combines work on the trauma memory with work on the appraisals of the hotspots. Work on appraisals and the behaviours that maintain them is also closely linked, for example in behavioural experiments. CT-PTSD is a trauma-focused treatment and aims to work on updating trauma memories and discriminating triggers early in treatment as this work usually produces large symptom reductions. The order of interventions is always adapted to the patient’s individual case formulation and needs. Additional clinical problems may need to be considered in the formulation and may affect which interventions take priority. Here are two examples of such considerations:

For people who strongly dissociate when faced with trauma reminders, treatment might start with psychoeducation, normalising and using trigger discrimination to manage memory triggers and dissociation before progressing to updating the trauma memories. A risk assessment should include whether severe dissociation is impacting on childcare.

Some patients benefit from some work on cognitive themes prior to reliving or narrative writing. For example, a mother who was reluctant to talk about her trauma as she felt guilty and ashamed about feeling no joy at seeing her baby after her traumatic birth benefited from conducting a survey early in treatment and reading replies of mothers who had similar experiences. For patients with baby loss, imagery work can be helpful of the baby at peace before commencing memory work.

CT-PTSD during subsequent pregnancies

A common therapist concern is treatment of women with CT-PTSD during pregnancy. Although some aspects of therapy can activate high emotion, women who have PTSD will likely be experiencing daily distress that can significantly improve with treatment. Recent research indicates that treating PTSD during a normal (low risk) pregnancy is safe (Baas et al., Reference Baas, van Pampus, Braam, Stramrood and de Jongh2020). Depending on the stage of pregnancy, therapists may need to prioritise what can be covered in treatment if the full treatment cannot be delivered in time. We would see trigger discrimination as an essential part of treatment in this context as the triggers would be likely to be present during the birth. Co-working with mental health specialist midwives is also key.

Co-morbid depression

Postnatal depression is often co-morbid with PTSD, with rates of up to 72% (Dikmen-Yildiz et al., Reference Dikmen-Yildiz, Ayers and Phillips2017). At assessment, therapist and patient need to identify and agree the main problem that needs addressing. Exploring treatment goals, drawing out a timeline and using the magic wand question can help to identify the main problem where co-morbidity is present. Where depression is a secondary problem, reclaiming or rebuilding your life principles are important, with similarities to activity scheduling. However, memory work is important to bring into therapy as soon as possible, as reducing re-experiencing symptoms can often lead to improvement in mood.

If the depression is severe and may prevent the client from engaging in CT-PTSD, it will need addressing first. It is essential to do a risk screener and assessment where appropriate: asking about risk to self, risk to and from others and any risk to the baby or child. This needs to be done sensitively. Where risk is present, there is a clear need to involve the GP and other health professionals and emphasise to the patient the importance of them being supported. Mother and baby units may be considered where severe depression and risk are present.

Practical barriers

There can be practical barriers to patients accessing treatment, especially if the birth was recent. The therapist can help the patient to problem-solve how they can access treatment, for example considering childcare options, and may need to be flexible about how and where to offer appointments, including providing treatment remotely if needed or preferred, and welcoming babies into the session when possible and appropriate, which is common practice in perinatal settings.

PTSD in partners

Partners can develop PTSD from witnessing traumatic births and from baby loss. Partners often report feelings of powerless and being excluded during traumatic births (see Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Locock and Knight2014), as well as subsequent relationship difficulties (Nicholls and Ayers, Reference Nicholls and Ayers2007). Although it can be helpful to include partners in treatment, to the extent that the patient wishes, they should also be signposted to individual help where applicable. Common cognitive themes in partners overlap with those of mothers and include guilt, shame, anger, and anxiety that the mother or baby may die if falling pregnant again.

When memories from the past interfere