The central question of St. Erkenwald (late fourteenth/mid fifteenth centuries) is the central question of the alliterative tradition: how to uncover and understand the distant past. Consequently the narrative proceeds in two discrete stages, excavation (ll. 1–176) and interview (ll. 177–352). The plot can be summarized in one sentence, with a semicolon to represent the turning point between lines 176 and 177: in the seventh century, Erkenwald, bishop of London, discovers a tomb beneath St. Paul’s Cathedral covered in indecipherable carvings and containing the undecayed body of a pagan judge, who begins to speak to the astounded onlookers; after interviewing him about his life and death, Erkenwald unintentionally baptizes the judge by reciting the baptismal formula while shedding a tear. Throughout the poem, the Erkenwald poet constructs a “many-storied long-ago” so detailed that it threatens to overpopulate the simple past tense.1 With characteristic ambition, the poet extends the ‘olde-tyme’ prologue (see Ch. 4) far beyond a colorless reference to once-upon-a-time. The careful layering of historical frames in the first thirty-two lines of the poem is without peer in medieval English literature. For this poet, as for the Beowulf poet, the past is a foreign country that demands to be confronted. The tragedy of both poems is the intractability of history, the inevitability of loss in time. In Beowulf, there is always “æfter wiste | wop up ahafen” “lamentation taken up after feasting” (128; quoted from Klaeber’s Beowulf, ed. Fulk, Bjork, and Niles; translation mine). In St. Erkenwald, “Meche mournynge and myrthe | was mellyd togeder” (350; all quotations of St. Erkenwald are from St. Erkenwald, ed. Savage).

This chapter reads St. Erkenwald as a serious meditation on history. The second section contrasts St. Erkenwald with some short English alliterative poems embedded in Latin prose and rhyming English verse, in an effort to infer the connotations of the alliterative meter in late medieval English literary culture. I argue that the Erkenwald poet’s sense of history and use of alliterative style are more robust than the impression of an archaistic alliterative meter shared by some thirteenth- and fourteenth-century writers and some modern critics of St. Erkenwald. The third section provides reasons to doubt the traditional attribution of St. Erkenwald to the Gawain poet. I argue that, in the context of the alliterative tradition, an understanding of poetic style per se is both more important and more attainable than knowledge of the corpora of anonymous authors.

A Meditation on Histories

Again and again, St. Erkenwald returns to the ever-since, the past imagined as the swathe of time separating a foundational event from the present. The poet begins by juxtaposing the two meanings of the adverb/conjunction sythen ‘afterwards; ever since’: “At London in Englonde | noʒt fulle longe sythen/ Sythen Crist suffride on crosse, | and Cristendome stablyde” (1–2). Bishop Erkenwald’s London is located in living memory (“noʒt fulle longe sythen”), but also, paradoxically, deep in Christian history. The contrast is so abrupt that Israel Gollancz replaced the first sythen with tyme in his edition of the poem, nullifying the ambiguity. The vacillations between the short view and the long view set the stage for the anachronistic resurrection to come. The bishop is introduced as “Saynt” and “þat holy mon” (4), titles that superimpose on Erkenwald’s life his post-mortem history as a pilgrimage destination. From the start, present and past overlap:

To understand the rededication of the temple (5–6), one must remember the Gregorian mission (12) to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons (7), who in turn had come to the island from Saxony (8) and conquered the Britons (9–10). The chronological contortions are so fierce that it is unclear how many Christian dedications St. Paul’s is supposed to have undergone.2 The uncertainty reflects the poem’s anxieties about burying the past. The Erkenwald poet imagines history as a mess of renovation and apostasy, not linear but “geometrical.”3 The view is of a longue durée, comprehending centuries of wasted time and dead ends: “Þen wos this reame renaide | mony ronke ʒeres.”

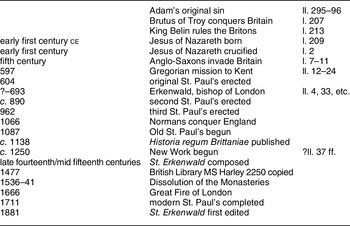

Like Beowulf, St. Erkenwald makes the question of history explicit by hinting at the future of the past it narrates. The world of bishop Erkenwald (d. 693) is itself remote from late medieval England, as cued by “In his tyme” (5). When he sits in the “New Werke” (38), Erkenwald occupies a cathedral church as yet unbuilt. The New Work was a Norman addition c. 1250 to the edifice now remembered as Old St. Paul’s, itself constructed in 1087, 400 years after the death of the historical Erkenwald. The reconstruction that is the occasion of the poem (37 ff.) could be an imaginary seventh-century renovation of St. Paul’s or the eleventh-century renovation and thirteenth-century addition transposed to seventh-century London. The poet’s note “Þat was the temple Triapolitan” (36) might refer to a pre-Christian historical reality, the historical consciousness of the Londoners in the poem, or the historical consciousness of the late medieval audience. In a grotesque gesture that presages the discovery of the corpse, the poet has the saint preside over his own future resting place: the historical Erkenwald was buried and later enshrined in St. Paul’s. During the poet’s lifetime the shrine was located in the New Work, where it was to remain until the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–41). The invocation of the successive edifices of St. Paul’s mirrors the deconstruction and reconstruction on which the narrative turns. Pagan St. Paul’s haunts the seventh century, and modern St. Paul’s lies in the ruins of an ancient temple, waiting to be built. The corpse doubles the historical Erkenwald, as though it were his own body that the bishop discovers.

It would be easy to identify inconsistencies in this powerful opening, but to do so would be to overlook more important symmetries. For the Erkenwald poet, the past is entirely implicated in the present. The aim of St. Erkenwald is not to achieve historical accuracy, whatever that might be, but to expose the inner workings of historical memory. Anglo-Saxon London comes to bear not only the imprints of past conquests, but, eerily, the imprints of future ones (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. The Pasts, Presents, and Futures of St. Erkenwald

London is detached from England, “þat toun” (5) from “this reame” (11), only to be celebrated as the crossroads of British history. The poet’s own spatial relationship to London parallels the temporal paradoxes of the poem. Possibly from Cheshire, in the first line the poet plays the outsider, though the poem betrays extensive knowledge of the metropolis.4

If poet and audience remain aware of the antiquity of Anglo-Saxon England, the narrative itself focuses on the pre-Saxon British past. Like every other past in St. Erkenwald, its legacy is ambivalent. A great deal of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s British history predates the birth of Christ, including the reign of King Belin, under whom the pagan judge says he served (213). Geoffrey presents the Britons as the rightful first owners of the island, and a good Christian people from the birth of Christ to the adventus Saxonum. The Saxon invaders, led by Hengist, are double-crossing heathens. At the same time, a historiographical tradition originating with Gildas’s De excidio et conquestu Brittaniæ (sixth century) cast the Britons as a corrupt and querulous people who received their comeuppance at the hands of the Saxons. The Viking incursions of the ninth and tenth centuries were subsequently freighted with a similar moral import. The knowledge that Britain had been pagan before the birth of Christ, Christianized thereafter, re-paganized by the adventus Saxonum, re-Christianized by the Gregorian mission, and visited with destruction by the pagan Vikings, held rhetorical value for Bede, Alcuin, Wulfstan, and Gerald of Wales, among others.

Because medieval historians imagined Christianity on the island as a cycle, there was the potential for slippage between the pagan Britons and the pagan Saxons. Each conquest and each conversion forecasts a future one. The Erkenwald poet is content to assemble the elements of late medieval British historiography without organizing them into an exemplum. The “ambivalence toward the past” that Daniel Donoghue identified in Lawman’s Brut characterizes St. Erkenwald, too.5 By reversing a Monmouthian translatio imperii, the poet has London become ‘the New Troy’ in the judge’s mouth: “I was (o)n heire of an oye(r) | in þe New Troie, / In þe regne of þe riche kynge | þat rewlit us þen” (211–12; cp. 25). Then, as though by a translation that reverberates backwards through time, a death in New Troy causes lamentation in Troy itself: “And for I was ryʒtwis and reken, | and redy of þe laghe, / Quen I deghed, for dul | denyed alle Troye” (245–46; cp. 251 and 255). The Old Troy becomes shorthand for, or even replaces, the New. Each familiar connection – between colony and motherland, name and namesake, past and ulterior past – is emphatically drawn only so as to be just as emphatically reversed.

Like the Beowulf poet, the Erkenwald poet dwells on pagan rites:

Beyond the condemnatory buzzwords lies a curiosity about ancient customs. The Saxon temple was named for the most important god. Its function, we are told, was sacrificial. The treatment of heathendom does not come any closer to relativism than the parallel passage in Beowulf (175–88). But neither is the pagan world fully eclipsed by the evangelical activities of Augustine (12–24). In seeking to finish burying the pagan past, bishop Erkenwald accidentally accomplishes the opposite. The past returns, unbeckoned, from the earth. The discussion of pagan religion is no simple denunciation, for it names an ancient world that comes hurtling back from beyond the grave, visceral and authentic.

The pagan judge was entombed with as much pomp and circumstance as Beowulf (247–56). The poet emphasizes the exotic meaning of the burial garments. What the Londoners (98) and even the narrator himself take to be royal vestments (77 “rialle wedes”) are really “bounty” (248) for exceptional virtue. In “a fine display of chronological wit,” the antiquarian and the anachronistic coincide: the pagan judge is buried like a late medieval justice, confusing the seventh-century Londoners.6 The circumstances of the judge’s burial indicate a pre-Christian morality, without confirming whether this morality can coincide with Christian doctrine: “Cladden me for þe curtest | þat courte couthe þen holde, / In mantel for þe mekest | and monlokest on benche” (249–50). Like another pair of superlative m-words hanging out at a pagan funeral (Beowulf 3181 mildust and monðwærust), mekest and monlokest call to mind the Christian virtues of humilitas and caritas, even as they expose the anachronism of that association. Where the Beowulf poet leaves the Christian exorcism of the past to the audience’s imagination, the Erkenwald poet has the past talk back to the present directly, with a will and a moral code proper to itself. Pagans even harbor their own expectations for the future, as when the judge is deemed most virtuous “of kene justises, / Þ(at) ever wos tronyd in Troye | oþer trowid ever shulde” (254–55). This alien past is both alluring and terrifying. It invites evangelism and provokes self-reflection in equal measure.

St. Erkenwald comes much closer than Beowulf to a Christian synthesis of past and present, and the poem is often read as an allegory of salvation history. It has been compared to the popular Gregory-Trajan legend, on which it is loosely based. The poet takes pains to stay within the bounds of late medieval orthodoxy.7 But St. Erkenwald is more romance than hagiography. Its overall effect is to raise historical questions, not to settle theological ones. The inscription on the judge’s tomb, for example, becomes a scene unto itself:

The poet packs all of London into St. Paul’s, but no explanation is forthcoming. The writing is “roynyshe” “mysterious(?),” a word whose possible affiliation with Old English run ‘mystery; runic letter’ might not have been lost on poet or audience.8 There is a decorum in this. The inscription is ‘all runes’ to the seventh-century Londoners, just as Anglo-Saxon runes would be inscrutable to late medieval Englishmen, and just as the origins and meaning of roynyshe are newly murky in modern times. Each age gets the mysterious script it deserves. Tantalized, the Londoners perceive that the writing is clear and precise (“Fulle verray”), but its meaning eludes them utterly. There is no Daniel to decipher the inscription, as in the other alliterative tableau in which curious writing is ‘runish’ (Cleanness 1545). Nor does there conveniently appear an old man “quite erudite in scripts [litteris bene eruditum],” as in a similar inventio narrative attributed to the tenth century in Matthew Paris’s portion of the Gesta abbatum monasterii S. Albani (early thirteenth century).9 In St. Erkenwald, workmen remove the lid of the tomb, revealing the greater mystery of the undecayed body. One confrontation with the long ago has passed, but it is never resolved.

The poet hints that the contents of the tomb will remain unintelligible, too, even before they are disclosed to the reader:

The cinematographic sleight-of-hand creates a sense of wonder that supersedes its very object. The syntactic reversal around “Bot” is pointed, suggesting as it does that the Londoners’ hopes are raised only to be frustrated by the unknown. The poet uses bot in the same way at 52, 54, 101, 156, and 263.

Deprived of the tell-tale signs of decay, the onlookers are thrown into doubt about the age of the corpse:

In keeping with the historical prologue, the importance of the relic is its superdurability. Like baffled archaeologists, the bystanders do not wonder ‘when’ but “How longe” (cp. 147 and 187).10 They can see that this is no illusion, that the man must have meant something to someone:

Even the man’s (unknown) reputation is set on a large time-scale (“longe”). But neither memory nor written record can explain the discovery:

And the answer matters. Messengers reporting to bishop Erkenwald tell of “troubulle in þe pepul” (109), and “pyne wos with þe grete prece” (141) who re-enter the tomb. The dean goes so far as to imply that one scrap of information about the John Doe would be worth the cathedral’s entire necrology:

The frustration is palpable. While the poem self-consciously aligns itself with the Brut tradition (“As ʒet in crafty cronecles | is kydde þe memorie,” 44), it portrays a “mervayle” (43, 65, 114, etc.) that surpasses the limits of human knowledge. Somehow, the man has managed “To malte … out of memorie” (158). And yet there he lies. The “toumbe-wonder” stumps an entire library: “And we have our librarie laitid | þes longe seven dayes, / Bot one cronicle of þis kynge | con we never fynde” (155–56).

There is something uncomfortable about the apophaticism with which bishop Erkenwald attempts to reassure the populace:

Emphasis seems to fall as heavily on human ignorance, “quen matyd is monnes myʒt, | and his mynde passyde, / And al his resons are torent, | and redeles he stondes,” as on divine omnipotence. Even as the unknowability of the pre-Christian past is folded into apophatic theology, the bishop’s words underscore the Londoners’ helplessness to explain the phenomena before them. If the onlookers can expect a divine answer to the questions that have been raised by the events of the poem so far, it is on pure faith.

The corpse might have been made to clear things up when he begins speaking. Instead, he declares his own antiquity to be unfathomable before launching into a supremely obscure reckoning:

Calculation fails. Christian chronology itself fails (“þat is a lewid date”), despite the modern editor’s best efforts.11 Like the letters carved into the lid of the tomb, the corpse proves an unreadable relic.

When the body speaks, the people are distressed:

The reaction of the onlookers expresses not so much pity on a heathen soul as the unspeakable horror of reanimation. For all that the resurrection of the judge recalls typologically the Resurrection of Jesus, in the world of the poem it embodies the unaccountable. The verbs convey violent surprise (sprange, forwrast). After hearing the judge’s story, Erkenwald responds “with bale at his hert” (257), another affective description that seems to slide away from pity toward terror. When Erkenwald looks “balefully” (311) and the townsfolk weep “for woo” (310), it is as though they share in a dark damnation they can scarcely imagine.

The sense of a doomed and inaccessible past is confirmed, not dissolved, by the judge’s ad hoc baptism. The poet allots one line to the ascent to heaven, but labors over the disgusting residue:

The mismatch is not altogether glossed over by the platitude that bodily decay heralds spiritual immortality (347–48). An unmistakable ambivalence rings through the final image of the poem:

No tidy ‘amen’ can be appended. Are the bells ringing for a baptism or a funeral?12 Are the people weeping for the death of a righteous man or the dreadful end of a mysterious episode? If the former, the Londoners recall the judge’s contemporaries at his first death, who, he says, “Alle menyd my dethe, | þe more and the lasse” (247). Do the pagans resemble the Christians, or vice versa? The message of Christian consolation is there for any reader interested in extracting it, but it coexists with a vision of an irrepressible un-Christian past that haunts the foundations of the Christian present. St. Erkenwald begins and ends not in heaven but on earth, not in spiritual bliss but in postcolonial unease. The analogy to modern postcolonial contexts is approximate, of course, but it helps elucidate the historiographical and linguistic effects of the cyclical conquests of medieval England, which fire the historical imagination of St. Erkenwald.13

St. Erkenwald and the Idea of Alliterative Verse in Late Medieval England

If St. Erkenwald seems unusually sophisticated in its treatment of the distant past, one might ask how much the poet owes to the conventions of alliterative poetry specifically as opposed to romance generally. Alliterative poets’ avoidance of reflexive statements about metrical form may disappoint modern expectations, but it also serves as a reminder that the alliterative meter remained available as an unselfconscious choice long after the ascendance of syllable-counted English meters.14 One way of measuring the connotations of a verse form that has left behind no ars poetica is to read the moments when it interacts with adjacent literary traditions. After 1250, there seems to have been cachet in flaunting a familiarity with alliterative poetry and its supposed generic limitations. So for example the unique copy of an alliterative epitaph was made because a late thirteenth-century compiler invented “a leaden vessel [quoddam vas plumbeum]” on which the verses were supposed to have been engraved centuries earlier, then “rediscovered [inueniebantur]” beneath a chapel in Shrewsbury.15 Fully six of the twelve short alliterative poems that survive from the period 1125–1325 are proverbs quoted in passing by authors or scribes writing in Latin, e.g., the one-line maxim prefaced by “whence a wise man said [unde senex dixit]” at the end of a Latin legal note in the margins of two copies of Henry de Bracton’s De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliæ (c. 1235).16 Like the Old English Proverb from Winfrid’s Time (eighth century) and Bede’s Death Song (eighth/ninth centuries), short gnomic poems that survive only indirectly, in Latin contexts, these twelfth- and thirteenth-century alliterative snippets showcase sententiousness and vernacularity. The appreciation of alliterative verse as a literary form was of little concern to these authors and scribes, who produce only enough homespun wisdom to prove their points.

By the fourteenth century, the alliterative meter has assumed a minor position in a newly diversified metrical landscape. The oft-quoted remark by Chaucer’s Parson that he “kan nat geeste ‘rum, ram, ruf,’ by lettre” (Canterbury Tales X 43) is not primarily intended to denigrate alliterative verse but to characterize the Parson as one totally lacking in poetic skill. If alliterative meter is not supposed to rate highly for Chaucer’s fashion-forward audience, it nevertheless makes the short-list of forms that lie beyond the Parson’s abilities. That he rhymes “but litel bettre” (X 44) and is “nat textueel” (X 57) belies the Parson’s excuse for foregoing alliterative meter (“I am a Southren man,” X 42), and it is by no means certain that Chaucer is here endorsing the designation of alliterative verse as lowbrow, provincial, and generically typecast. The immediate meaning of the reference seems to be only that a bumbling southerner would be likely to disparage alliterative poetry in this way. Ultimately, the value of mentioning the “‘rum, ram, ruf,’ by lettre” may not be metropolitan snobbery so much as the implication that Chaucer himself was better informed about alliterative verse. Indeed, in two much-discussed battle sequences (Canterbury Tales I 2601–20 and Legend of Good Women 637–49), Chaucer adorns his pentameter with alliteration in an apparently unironic gesture toward alliterative chivalric romance.

Chaucer’s other use of “geeste” (<OF) as a formal term, this time as a noun, does little to clarify his perceptions of the alliterative tradition. After he has interrupted the mock-romance Sir Thopas, the Host’s injunction to Chaucer the pilgrim to “tellen aught in geeste” (VII 933) cannot refer to romance generally, yet it is unclear whether it can refer to alliterative romance specifically (as the note in the Riverside Chaucer guesses on the basis of X 43). Geeste is here explicitly opposed to either rhyming or versification generally (“ryme” [vb.], VII 932). Elsewhere in Chaucer, “geestes” are classical and/or lengthy (hi)stories (Canterbury Tales II 1126, III 642, and IV 2284; House of Fame 1515 and 1518; etc.). Moreover, both Canterbury Tales passages draw a primary formal distinction, not between alliterative and non-alliterative meters, but between (alliterative) romance and (didactic) prose (“telle in prose somwhat,” VII 934, and “I wol yow telle a myrie tale in prose,” X 46). Chaucer expects his audience to recognize the alliterative tradition as one territory within this broader formal/generic division. The difficulty of mapping medieval testimonia about poetic form onto modern analytical categories illustrates the extent to which such testimonia emerge under pressure from other kinds of historical discourse, in this case discourses of class, literary genre, and regionalism.

Comparison between St. Erkenwald and these proverbs and one-liners begins to define a continuum of perception and practice within which the alliterative tradition operated in the late medieval centuries. A different kind of verbal showmanship might explain what four alliterative long lines are doing in the mouth of John Trevisa’s clerk in the Dialogus inter dominum et clericum, which prefaces Trevisa’s English translation (1387) of Ralph Higden’s Polychronicon (quoted from Waldron, “Trevisa’s Original Prefaces,” p. 293):

Dominus: … [Ich] wolde haue a skylfol translacion þat myʒt be knowe and vnderstonde.

Clericus: Wheþer ys ʒow leuere haue a translacion of þeuse cronyks in ryme oþer yn prose?

Dominus: Yn prose, vor comynlych prose ys more cleer þan ryme, more esy and more pleyn to knowe and vnderstonde.

Clericus: Þanne God graunte grace [greiþlyche] to gynne, <w>yt and wysdom wysly to wyrche, myʒt and muynde of ryʒt menyng to make translacion trysty <and> truwe, plesyng to þe Trynyte, þre persones and o god in maieste, þat euer was and euere schal be.

Asked by his patron to effect a translation “yn prose,” the cheeky clerk produces four alliterative lines followed by three monorhyming lines in four-stress verse (lineation mine, and one addition to Waldron’s text in square brackets):

The use of the ‘God-grant-grace’ prologue (see Ch. 4) solemnizes the sermon on Creation that follows the poem and concludes the Dialogus, and it even, perhaps, consecrates the translation as a whole. One might compare similarly worded invocations at the close of two fourteenth-century sermons in English and in the concluding lines of Piers Plowman B 7, marking the end of the Visio and beginning of the Vita de Dowel.18 Indeed, two manuscripts of the Dialogus (Waldron’s S and G) end the preface with Trynyte, making the clerk’s reply into a pithy metrical coda.

Yet there seems to be a joke in the clerk’s spontaneous versifying, whether it is on the lord, the clerk, or alliterative meter itself. Perhaps alliterative verse, which Trevisa will approach with some circumspection in the St. Kenelm episode (see below), is ironically supposed to be even less “esy” and “pleyn to knowe and vnderstonde” than the “ryme” that the lord rejects. Perhaps, too, Trevisa has his clerk quibble on ryme ‘verse’ but also ‘rhymed verse.’ In any event, the appearance of alliterative verse in this context shows that alliterative meter still had some currency (but only as a punchline?) in the most educated southern circles in the last quarter of the fourteenth century. Certainly the composition bears no signs of ignorant imitation. The double poetic inversion in l. 3 (prose order myʒt and muynde to make menyng of ryʒt) is particularly idiomatic. The coincidence of alliterative verse with chronicle writing resonates with St. Erkenwald. As before, however, the contrast between an apparently lighthearted exchange and the high seriousness of our poem registers the extent to which the alliterative tradition had become conspicuously marked in literary culture by the end of the fourteenth century.

A vignette from St. Kenelm in the South English Legendary (late thirteenth century) provides the most intensive contemporary reaction to alliterative verse. It speaks volumes about the English literary scene on the eve of the fourteenth century that the reaction comes from a non-practitioner. Two lines of alliterative verse lie embalmed in the end-rhymed saint’s life, standing in for mystery, sanctity, the manuscript page, and above all Englishness (quoted from South English Legendary, ed. D’Evelyn and Mill, ‘De Sancto Kenelmi’; D’Evelyn and Mill’s medial punctuation replaced with a tabbed space):

As in the Latin Vita Sancti Kenelmi (1045–75), on which St. Kenelm is based, the document leads to the rediscovery of the saint’s body (“Hi lete seche þis holy body | and fonde it oute iwis,” 287). The poet sets in motion many correspondences – between sacred text and sacred corpse, between Rome and Canterbury, between human knowledge and divine dispensation. The poet’s diffidence toward the vernacular is in line with the ‘choice of English’ topos popular at the turn of the fourteenth century.19 On the one hand, English is an arcane skill that the Pope, naturally enough, does not possess. On the other hand, English is God’s language here. (The South English Legendary goes on to narrate the ‘Angle’/‘angel’ pun made by Pope Gregory I, who did learn a little English.) The obscurity of English authorizes its efficacy as “holy writ.”

The alliterative snippet, of late eleventh- to early thirteenth-century vintage, circulated on its own and as a gloss to the corresponding scene in three manuscripts of the Vita Kenelmi.20 Whereas the letter in the Vita is a means to an end, in St. Kenelm the writ itself becomes “iholde for grete relike” (270). The difference lies in the declining reputation of alliterative verse. Alliterative meter was the only English meter in 1075, when the Vita was written, but it becomes a marked choice in the context of the late thirteenth-century vernacular legend. The Kenelm poet exploits the newly antiquated feel of alliterative verse, turning the document itself into an embodiment of the distant Anglo-Saxon past (“olde dawe,” 19). Unlike the late eleventh-century author of the Vita, the late thirteenth-century Kenelm poet notes the salient feature of this verse form: it lacks rhyme (“wiþoute rime,” 266 – though a different plausible translation would be ‘without metrical form’).

The Kenelm vignette summarizes the bounds assigned to alliterative poetry by writers who had long since moved on to newer forms. Alliterative verse becomes useful only when one wants something antiqued, sententious, and profoundly vernacular. The message delivered by the dove represents what every Englishman recognizes upon hearing it (“þo hi it hurde rede,” 264), and yet its dramatic purpose is to be translated out of English, presumably into Latin, for the Pope. In some manuscripts of St. Kenelm the English snippet is glossed by the rhyming Latin couplet found in the Vita, while the earliest manuscripts of the Vita lack the English snippet altogether. To judge from the activities of scribes and readers, it is as though the anticlimactic translation of the divine instructions had occurred in reverse, Latin to English. The Pope’s message for the Archbishop of Canterbury (278–84), presumably also in Latin, conveys in plain terms the location of Kenelm’s body, without reference to the language or poetic form of the writ. The translation of the text makes possible the translation of the corpse. The alliterative poem, like the body it homes in on, has value not in itself but in what God imparts to it – in both cases, perfect purity (“wittore þanne eni snou,” 253; “ssinde briʒte | þe lettres al of golde,” 256; and “pur Engliss,” 265) encased in perfect substantiality (“Þis writ [was] wiʒt,” 256). This is how alliterative poetry should be treated: decode it when a saint’s body is at stake, then enshrine it as a relic. In St. Kenelm, the alliterative snippet is little more than a curious impediment. There can be no doubt that the poet would have ignored alliterative verse altogether if his source had not contained two lines of it. Retelling the anecdote of the sacred letter in his English translation of the Polychronicon, Trevisa already felt the need to translate from alliterative verse to “Englisshe þat now is used.”21 Viewed from the outside, alliterative poetry seemed nearly as old-fangled in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as it does today. Who needs a Revival?

In a powerful reading of St. Erkenwald, Christine Chism argues that the tomb is an apt metaphor for the Alliterative Revival itself. For Chism the tomb represents “the break between a forgotten past and a barely incipient present” that symbolizes alliterative poets’ “deliberate archaism” and “invention of a tradition.”22 Chism is surely correct to identify the tomb as a mise en abîme. It may be the most overt mise en abîme in the entire alliterative tradition. However, the previous chapters have argued that the alliterative long line was never reinvented from scratch. The condescension of some more progressive Middle English authors did not sum up all possible uses of alliterative verse. The Otho revision of the Brut, roughly coeval with the composition of St. Kenelm and the copying of the Shrewsbury epitaph and the Bracton proverb, holds the capabilities of alliterative poetry in higher esteem. From the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, some poets continued to find the alliterative meter suitable for serious work. The deprecations foist upon alliterative verse by certain increasingly influential sectors of literary culture did not destroy it, but radicalized it.

The meaning of the tomb in St. Erkenwald can be revised in light of the verse history narrated in the previous chapters. Chism’s book explores the presentist meaning of the tomb (‘Of what use is it to us?’) by carefully situating alliterative poetry in fourteenth-century politics and social history. Thus her chapter on St. Erkenwald reads the poem as a response to “the late [sc. fourteenth-]century social mobilities – physical, occupational, and class-jumping – that were recreating the London civic landscape.”23 The durability of the alliterative tradition directs attention instead to the historical meaning of the tomb (‘From what sort of world does it come?’). The gratuitously perplexing details in the poem, the focus on wonder and terror rather than pity and joy, indicate which question our poet preferred to pursue. The fulfillment of the tomb’s immediate purpose in the retroactive baptism seems little more than a pretext for the real motives of the poem. This is just the opposite of the Shrewsbury epitaph and the alliterative writ in St. Kenelm, which make better targets for Chism’s arguments. Whereas the epitaph survives because of its retrojection into an antiquarian, Latinate, hagiographical scene, and the writ quickly yields up its secret and outlives its usefulness except as a ‘ye olde’ sign, the “roynyshe” writing lingers on past the end of St. Erkenwald, emblazoned on a now-empty tomb and still untranslated.

By way of conclusion, I would like to suggest a direct relationship between the two main strands of the argument thus far, the Erkenwald poet’s sense of history and the idea of alliterative verse in late medieval England. St. Erkenwald not only instantiates the idea of alliterative verse; it also responds to that idea poetically, though in a different way, I believe, from the one proposed by Chism. Like the Kenelm episode, St. Erkenwald explores the limits of language, knowledge, and bodies. In St. Erkenwald, however, these stereotypical preoccupations of alliterative verse are modulated into a richer historical vision. Here I identify some points of contact between the historical imagination of St. Erkenwald, late medieval stereotypes about alliterative meter, and alliterative verse history as reconstructed in this book.

For a late medieval composition, St. Erkenwald is “full of oddly advanced notions.”24 Its achievement is not to redeem the past, but to traverse a longue durée so broad that it connects Christianity with what Christianity would repudiate. In the course of events every possible response to this conjunction is mooted, but none is endorsed. Like the squabbling clans of Beowulf in the wake of the hero’s death, the Londoners of St. Erkenwald seem doomed to squander the legacy of the past. Construction grinds to a halt; the hoi polloi just gawk. After a week of research and prayer, the tomb is as inscrutable as ever. The tearful baptism is inadvertent and of debatable sacramental efficacy. An attentive late medieval reader would have wondered why God preserved the corpse in the first place, whether He therefore preserved others, what the inscription meant, how old the judge was, what sort of England he lived in, and whether pagan souls could, or should, be saved by baptism. Six hundred years have not made any of these questions easier to answer. The bishop’s confrontation with the unknown is all the more striking for being unexpected. No one in St. Erkenwald goes in search of a tomb, or a judge, or a pagan past. Tomb, judge, and past simply materialize. The Erkenwald poet discerns doctrinal, linguistic, and sartorial hysteresis in cultural history, mirroring the metrical hysteresis that this book discerns in verse history.

The will to remain open to the unknown bespeaks a subtler historical sense than is typically imputed to medieval thinkers. Hints at the limits of historical perspective are thin on the ground in most of the genres inhabited by St. Erkenwald (chronicle, hagiography, inventio, romance). Langland’s treatment of the Trajan legend (Piers Plowman B.11.140 ff.) is more overtly presentist. Centuries earlier, the Beowulf poet showed more interest in what could be learned and felt about the past than in its mysteries. These two comparanda indicate that the Erkenwald poet’s sense of history is subtle even by the stringent standards of the alliterative tradition. Certainly the genre of the inventio gives little precedent for curiosity about heathen life. For example, when Matthew Paris’s decrepit old man interprets the books found in the ruins of a large palace, Abbot Eadmar’s response is totally uncompromising. The large book, an account of St. Alban “whose rubrics and titles glittered in golden letters [quarum epigrammata et tituli aureis litteris fulserunt redimiti],” Eadmar “deposited most lovingly in the vault [in thesauro carissime reponebatur]” and “had faithfully and diligently expounded, and more widely taught in public by preaching [fecit fideliter ac diligenter exponi, et plenius in publico prædicando edoceri].” The other books, containing “fabrications of the Devil [commenta diaboli],” including “invocations and rites [invocationes et ritus]” to “Mercury, called ‘Woden’ in English [Mercurium, ‘Woden’ Anglice appellatum],” he burned immediately (“abjectis igitur et combustis libris”).25

The recognition in St. Erkenwald that the antiqui lived irrecoverable but possibly worthwhile lives seems exceptionally capacious. The poem’s interest in and evident sympathy for pagan England troubles the modern assumption that the salvation of pagan ancestors remained a live issue for only a few centuries after conversion.26 If the Erkenwald poet’s sense of history corresponds to anything in our own time, it is the postmodern turn in historical studies, with its sensitivity to cultural difference and its resistance to totalizing narratives. Without a doubt, the Erkenwald poet took it on faith that pagans were damned to hellfire. But this only makes the ambivalence of the poem more remarkable. The human desire to know the past challenges the specifically Christian desire to convert it. The moderni in the poem wait anxiously for the past to explain itself, or as the bishop has it, “Sithen we wot not qwo þou art, | witere us þiselwen” (185). The impulse to ask questions first, even if you plan to shoot later, is extraordinary in any century. Within a poetic tradition increasingly dismissed as archaistic in late medieval English literary culture, the Erkenwald poet staged an ambitious historical investigation.

Like the dragon’s hoard buried by the last survivor in Beowulf, the tomb in St. Erkenwald expresses the longevity of the alliterative verse form. To see history with the Erkenwald poet’s eyes is not, as Chism would have it, to colonize the past, but to realize that one is colonized by it.27 The familiar things of the present are undone, out of joint, forever altered by the long view. Undergirding this mode of historiography is an ethical imperative. Because the past cannot be cordoned off from the present, it must not be ignored. More than any other alliterative poem, St. Erkenwald dramatizes the necessary interrogation of the past, and the necessary failure of the interrogation. The lacrimae rerum of St. Erkenwald is the poignancy of a backward gaze conscious of its own futility. The plot may unfold along predictable religious lines, but the poet casts the Christian present far in the past as well. To apply the same historical method to Christian and pagan worlds is to imply, however faintly, that they belong to a progression greater than either. The sensation of belatedness, of being born after time or out of time, counterbalances the more familiar sensation of chosenness, raising an irresistible analogy between the Londoners and the pagan judge who knows himself “exilid fro þat soper so, | þat solempne fest” (303). Augustine’s regio dissimilitudinis lives in this poem in time as well as space. The demise of the alliterative tradition itself in the sixteenth century, around the same time as the destruction of the tomb of the historical Erkenwald, renders St. Erkenwald more poignant than ever. More acutely even than Beowulf, because more explicitly, St. Erkenwald senses its own transience in the transience of the past it figures forth.

Authors, Styles, and the Search for a Middle English Canon

Of all the questions raised by St. Erkenwald, the question of authorship has provoked the most speculation, on the slimmest evidence. It is a question about which the compiler of British Library MS Harley 2250, a late fifteenth-century anthology of hagiography, must have cared little. St. Erkenwald is no more or less anonymous than most other alliterative poems. Its connection in modern criticism with the Gawain group is based upon aesthetic similarities and the conviction that one “gifted poet” can be extricated from his metrical tradition.28 Middle English scholars, with good reason, have remained skeptical of the overstatements of oral-formulaic theory. Yet the ubiquity of formulas in alliterative poetry cannot be denied. Alliterative poetry may not be any more oral than other late medieval verse forms, but its formulaic style draws in its train all the difficulties of dating and attribution faced by Old English specialists.

Hard evidence for co-authorship of St. Erkenwald and the Gawain group, drawn from lexical, literary, and dialectal analysis, crumbles upon closer inspection.29 To connect St. Erkenwald and Gawain on the basis of vocabulary (as though nornen and gleuen were an author’s private property) is as optimistic as connecting them on the basis of literary value and surmised authorial dialect (as though the northwest Midlands were too small to contain two talented alliterative poets). Similarities between neighboring poems are to be expected. At any rate, so much manuscript evidence is missing that arguments from absence hold little weight. The handful of features unique to St. Erkenwald and the Gawain group, which some have found convincing, might dissolve if a dozen new alliterative poems came to light. The shared-words approach is an especially weak evaluative criterion as applied to a fragmentary corpus. It can be used, for example, to link Beowulf to conservative Old English poetry or late Old English prose.30 To believe that poetic style can diagnose authorship is to misapprehend the status of tradition and innovation in late medieval literary culture, not to mention the possibility of direct literary influence. Moreover, if St. Erkenwald was composed as late as the 1450s or 1460s, then its author cannot possibly have written Gawain in the second half of the previous century.31

More fundamentally, fixation on the authorship of St. Erkenwald is of dubious historical value to begin with. The author-centric format of the Norton anthology sends up the Romantic fantasy of transcendental, original genius, anticipated to some degree in the fifteenth-century reception of Chaucer. It is largely inapplicable to other medieval English poetry. (One might hasten to add that such ideology does not really fit the fifteenth-century reception of Chaucer either, or Romantic poets themselves, or perhaps, as suggested by recent poststructuralist critiques of the lyric, any poetry at all.) In my view, discussion of the corpora of anonymous authors co-opts the very features that might have pointed the way to a more fine-grained picture of literary communities. Affinities between St. Erkenwald and the Gawain group are matters of poetic style in the first instance. The identity of the author(s) is less important, except where it has traction as an organizational principle or a feature of reception in the Middle Ages. For the majority of alliterative poems, all such gestures toward an authorial canon remain the stuff of groundless speculation. Apart from Bede, Richard Rolle, and John Trevisa, who may or may not have composed one short alliterative poem apiece (Bede’s Death Song, “Alle perisches and passes,” and “Þanne God graunte grace,” respectively), William Dunbar is the only alliterative poet with a verifiable biography. Like Bede, Rolle, and Trevisa, Dunbar’s name survives on the strength of a large corpus of non-alliterative writings. The similarity in language, lexis, and style between St. Erkenwald and the Gawain group probably testifies to their close proximity in space and perhaps time. The primary value of these five poems from a literary-historical perspective is the way they symbolize a larger literary community now lost to history. Whether one, two, or five persons authored them seems much less important.

The irony of the co-authorship debate is that it has been unkind to St. Erkenwald, which figures in anthologies and criticism, if at all, as an optional addendum to an important foursome of poems – with which, again, not a single medieval reader, compiler, scribe, or author is known to have connected it. Like Beowulf, St. Erkenwald may have been stupendously unimportant, unread, unimitated, and quickly forgotten by contemporaries. Of course, modern scholars are under no obligation to take a medieval view of the poem’s literary merits (I certainly do not); but, equally, the poem is under no obligation to yield intelligible answers to modern questions. St. Erkenwald deserves separate treatment in any case, not because it is a work of genius that transcends its tradition, but because it epitomizes its tradition. For it is in one way, at least, a more perfect poem than Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: it crystallizes the problem of history with none of the distractions of chivalric romance. It could be called a “philosophical poem,” though that term fails to convey the vividness of the bishop’s encounter with the distant past.32

Controversy over the dating and authorship of St. Erkenwald underscores the relative paucity of alliterative poems that may be assigned to the mid fifteenth century or later. The next chapter tracks the development of the alliterative meter and the alliterative tradition from the late fifteenth century into the sixteenth century. Resisting the temptation to imagine (or simply dismiss) this poorly attested period of alliterative verse history as decadent, the chapter traces the generic, codicological, textual, and cultural contexts for alliterative meter in the century before it disappeared from the active repertoire of verse forms. In doing so, the chapter lays the groundwork for a new literary history of the sixteenth century.