Introduction

Our message to those who are … contemplating coming here illegally: We will send you back. … People in Central America should see and will see that if they make this journey and spend several thousand dollars to do that, we will send them back and they will have wasted their money.

Jeh Johnson, Secretary of Homeland Security, June 27, 2014 (CNN 2014)It is the policy of the executive branch to: …expedite determinations of apprehended individuals’ claims of eligibility to remain in the United States.

“Executive Order: Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements,” January 25, 2017 (White House 2017)Though stark contrasts have already emerged between the style and substance of the current Trump administration and the eight years of the Obama presidency, one common policy thread connecting the two is their concerted effort to send a message to individuals in northern Central America that if they migrate to the United States, they will be sent back. The emphasis on deterring emigration from this region is driven in large part by a rapid increase in migrants arriving from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador in recent years. Since 2009, apprehensions of non-Mexican border arrivals have increased over 350 percent, outnumbering for the first time in decades the number of apprehensions of Mexican migrants at the southwest border (CBP 2017). This surge in Central Americans arriving at the US border has coincided with unprecedented levels of crime and violence in the three northern countries of the region, raising parallels with the exodus of Guatemalans and Salvadorans fleeing the civil wars of their respective countries during the 1980s (Reference Carey and TorresCarey and Torres 2010; Reference CruzCruz 2011; Reference StanleyStanley 1987; Reference MenjívarMenjívar 1993).

Just as the Reagan administration insisted on referring to those refugees as economic migrants (Reference StanleyStanley 1987), Obama and now Trump have applied a policy approach premised on the idea that those leaving Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala are driven by the promise of what awaits them in the United States rather than the peril they face in their home countries. The “send a message” strategy seeks to deter future migration by detaining and deporting current migrants as expeditiously as possible. In this article, we show that a deterrence strategy that focuses on pull factors is likely to fail when the main push factor is one of life or death.

Using survey data from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, we first offer a systematic assessment of the relative weight crime victimization has on the migration decision alongside the more conventional socioeconomic and demographic predictors of migration. We then analyze data from a survey conducted in twelve municipalities across Honduras that included items specifically designed to assess respondents’ awareness of changes in the level of risk and probability of success involved in immigration to the United States.Footnote 1 With these data we are able to assess the degree to which the enhanced deterrence efforts of the United States mitigate the push factors of crime and violence in the case of Hondurans contemplating emigration. Although there is an abundance of research on the factors associated with emigration intentions (Reference Canache, Hayes, Mondak and WalsCanache et al. 2013; Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouacouci, Pellegrino and TaylorMassey et al. 1998; Reference Portes and HoffmanPortes and Hoffman 2003; Reference Donato and SiskDonato and Sisk 2015; Reference RyoRyo 2013; Reference SladkovaSladkova 2007), we know less about how individuals resolve this dilemma of whether to continue life in a high-violence context at home or flee and confront the increased risk of violence, detention, and deportation associated with immigration to the United States.

In the following pages, we show that although crime victimization does not strongly influence migration decisions in Guatemala, individuals in El Salvador and Honduras who have experienced crime firsthand multiple times are particularly likely to express intentions to migrate. Through our survey evidence from selected municipalities in Honduras, we find that these individuals persist in their migration plans even if they are fully aware of the dangers they are likely to encounter along the way and the high probability of deportation if they make it to the United States. From these results, it appears that in a situation of extreme levels of crime and violence, many individuals choose to leave this “devil they know” with the hope that the “devil they don’t” will be better. These findings highlight the need for increased attention to the root causes of violence driving these individuals from their homes, as well as the importance of providing full due process to asylum claims made by border arrivals from these countries in order to effectively and humanely manage a situation that increasingly seems to qualify as a refugee crisis.

The Roots of the Humanitarian Crisis and the US Response

In late June 2014, then US president Obama confronted an “urgent humanitarian situation”Footnote 2 along the US-Mexico border, as tens of thousands of unaccompanied minors and “family units”Footnote 3 were arriving at the border, turning themselves over to Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers, and initiating asylum claims. The rhetoric surrounding the purported causes of this “situation” emphasized the role of a misinformation campaign on the part of migrant traffickers. According to this narrative, those arriving at the border had been led to believe that they could obtain a permiso (permit) that would allow them to gain legal status in the United States. As Tae Johnson, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) official explained in an affidavit filed in a civil case involving the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), “recent border crossers … expect to be immediately released from custody … due to promises from human trafficking organizations that they will not be detained. … Detaining these individuals dispels such expectations” (italics added).Footnote 4

To address this urgent humanitarian situation, Obama adopted a multipronged “send a message” strategy, which included an expedited removal process for those individuals not passing their “credible fear interviews” (CFI), the denial of bond (and thus prolonged detention) for those who did pass their CFI, and a media campaign in Central America specifically designed to debunk the permiso rumor, highlight the dangers of migration, and stress the low probability of success. In a letter to Congress, Obama (Reference Obama2014) emphasized his goal of sending “a clear message to potential migrants so that they understand the significant dangers of this journey and what they will experience in the United States.”

In the first days of 2016, following yet another surge in the number of Central Americans arriving at the US border, the Obama administration appeared to use high-profile raids by ICE agents to again attempt to send a message by targeting, as former DHS director Jeh Johnson explained in his press release on January 4, “adults and their children who (i) were apprehended after May 1, 2014 crossing the southern border illegally, (ii) have been issued final orders of removal by an immigration court, and (iii) have exhausted appropriate legal remedies” (DHS 2016). The “send a message” goal of these actions emerged clearly in Johnson’s press release as well, as he appeared to speak directly to those individuals in Central America considering emigration by declaring, “As I have said repeatedly … if you come here illegally, we will send you back” (DHS 2016; see also DHS 2014).

The assumption on which this policy rests is that the decision calculus of migrants, and potential migrants, is driven by misinformation and an unrealistic assessment of their chances for a successful trip. According to this logic, when such views are corrected, those considering migration will stay home, regardless of the push factors at play. Such a premise, we argue, ignores the powerful impact that high levels of crime and violence can have on one’s emigration calculus. Simply put, the actual risks of daily life in a high-violence context will tend to be far more influential in the emigration decision than even the clearest and most accurate assessment of future risks. Though having a more realistic understanding of the risk involved may dissuade potential economic migrants, it is unlikely to have much impact on those trying to flee “the devil they know.”Footnote 5

Crime and Violence in Contemporary Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras

As of early 2017, Central America continued its position as one of the world’s most violent regions, with Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras ranking among the world’s most violent countries. At the peak of the “urgent humanitarian situation” in the summer of 2014, Honduras held the tragic distinction of being the murder capital of the world, only to be surpassed by El Salvador in 2015.Footnote 6 Survey data from the AmericasBarometer highlight the ways in which these trends led to sharp differences between Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras and their neighbors to the south in terms of the types of crime individuals typically confronted (see Table A1 in the appendix). Most telling, perhaps, are the high percentages of Guatemalan, Salvadoran, and Honduran respondents victimized by armed robbery, above 36 percent in each case, suggesting that not only are overall crime victimization rates higher in these countries than in other Central American nations, but violent crime victimization is high as well. Thus while crime across Central America is a concern, citizens of the region’s northern countries are living in a context of crime and violence that is quite distinct from their neighbors to the south.

To explore further this pattern of pronounced crime and violence in this region, we find from the 2014 AmericasBarometer data that respondents in five out of six Central American countries identified crime as the gravest problem in their country (see Figure 1). The data, however, demonstrate that the percentage of individuals considering crime as the main problem is significantly higher in Honduras and El Salvador, setting these two countries apart from even Guatemala in terms of the scope of the crime wave afflicting their citizens. The US Department of Homeland Security echoed this observation, concluding in its own assessment of the 2014 surge in US border arrivals from the region that “many Guatemalan children … are probably seeking economic opportunities in the U.S. [while] Salvadoran and Honduran children … come from extremely violent regions where they probably perceive the risk of traveling alone to the U.S. preferable to remaining at home” (as quoted in Reference Gonzalez-Barrera, Krogstad and LopezGonzalez-Barrera Krogstad, and Lopez 2014; italics added).

Figure 1 Percentage identifying crime as most important problem. Authors’ estimations based on data from the 2014 AmericasBarometer Survey.

The recent origins of this security crisis lie in the political and economic changes that swept the region in the 1980s and 1990s. During this time, representatives from warring factions in both Guatemala and El Salvador signed peace treaties that brought an end to long-standing civil wars in these countries and inaugurated competitive democratic elections. After decades of conflict, these nascent democracies had to construct new domestic police forces while simultaneously disarming combatants, rebuilding infrastructure, and reintegrating into society many of those who fled to the United States or other countries during the years of violence. The combination of unemployed former combatants and an inexperienced domestic police force created conditions for crime to thrive, particularly given the historical context of high levels of poverty, inequality, and violence in these countries (Reference CruzCruz 2011, Reference Cruz2003; Reference LevensonLevenson 2013; Reference MaloneMalone 2012).

US policy further aggravated these postwar problems with the deportation of record numbers of Salvadoran gang members back to El Salvador, where most were not able to integrate themselves into the legal economy (Reference CruzCruz 2011, Reference Cruz2003; Reference WolfWolf 2017). These Salvadoran gangs (or maras) were infamous for their excessive violence, a characteristic due in part to the fact that many members had witnessed and, in some cases, participated in the well-documented atrocities of the civil wars of the 1980s (Reference LevensonLevenson 2013; Reference MenjívarMenjívar 2000). As Levenson notes, many of the combatants in these conflicts were mere children at the time, trained to commit violent acts of cruelty that they would later employ as mareros.

Honduras did not have a civil war, but its geographic proximity to the wars of its neighbors meant it faced many of the same problems. During the civil wars of the 1970s and 1980s, tens of thousands of refugees fled to Honduras, and insurgents used Honduran territory to launch attacks across the border (Reference Millet, Millet, Holmes and PérezMillet 2009). Peace treaties ended these wars in the 1990s, but in Honduras many refugees and former combatants remained in the country and often were not able to find jobs in the formal economy. As in the postconflict countries, democracy replaced authoritarian rule in Honduras in the 1990s, and the new democratic government faced the formidable challenge of disarming former combatants, creating new institutions, and addressing the needs of citizens.Footnote 7

Adding to these challenges was the rise in drug trafficking throughout much of the region during this time. With porous borders, limited state presence in remote areas, and traffickers in search of new routes to transport illicit drugs into the United States following crackdowns on Caribbean routes, the drug trade exploded during the early 2000s. Indeed, when antidrug operations disrupted Colombian and later Mexican drug trafficking organizations, the illicit drug market rerouted many of its transit routes through Central America. In 2006, 23 percent of cocaine shipments moving north passed through Central America; by 2011, this amount had jumped to 84 percent (Reference Archibold and CaveArchibold and Cave 2011). Political instability in Honduras following the 2009 coup created additional opportunities for drug traffickers, who took advantage of a weakened state to increase their illicit activities (InSight Crime 2016). This shift in drug trafficking corridors corresponded to increases in violence, particularly in El Salvador and Honduras.

Understanding Emigration in a High-Crime Context

To understand the motivations behind an individual’s decision to leave her home and set off on a dangerous journey in hopes of settling in another country, we first must recognize that the emigration decision calculus even in the best of circumstances is one driven by myriad political, economic, and familial considerations. For Central Americans, the decision is even more complex in that it represents a choice replete with risks no matter which option is selected. Further, many individuals living in high-crime contexts are also economically vulnerable, muddying even further the conventional dichotomous treatment of migrants as driven by either economic or noneconomic considerations.Footnote 8 A growing body of work on the unique characteristics of the Central American migration flows in recent decades serves as the point of departure in our effort to understand the roles crime and violence have played in the emigration decisions of those living on the front lines of the most violent region of the world.

To begin, there is ample research on the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics associated with economic migrants from traditional sending countries such as Mexico (e.g., Reference Massey, Durand and MaloneMassey, Durand, and Malone 2002). First, such migrants tend to be between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five, male (though this varies by country), and relatively well educated. Second, the emigration decision tends more often to be made collectively by members of a family and driven by the economic needs of the household, rather than made by an individual based on his or her economic concerns (Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouacouci, Pellegrino and TaylorMassey et al. 1998; Reference MasseyMassey 1990). Perceptions of the household’s economic situation and its future prospects, then, tend to carry a significant weight in the migration decision. Moreover, since considerable resources are necessary to fund a migrant’s trip, those households with some type of income stream will be more likely to consider emigration as viable. Thus, we should not expect the poorest of the poor to make plans to emigrate, just as we should not expect the very wealthy to emigrate either. Rather, migrants tend to come from those households with enough of an income stream to make emigration viable, but not so much to make emigration unnecessary.

Because of the region’s tumultuous, violent past, this standard economic migrant narrative does not work nearly as well for Central American emigrants. Menjívar’s work (Reference Menjívar1993, Reference Menjívar1995, Reference Menjívar2000) highlights the complex mix of economic, political, social, and historical factors that drove Salvadoran migration throughout the twentieth century. In a similar vein, Stanley (Reference Stanley1987) explored at an aggregate level the relative roles of economic and political conditions in explaining Salvadoran migration during the 1980s, finding, not surprisingly given the ongoing civil war at the time, a significant role for political violence in the country’s migration rates.Footnote 9 In interviews with Salvadoran immigrants in San Francisco, Menjívar (Reference Menjívar2000) documents how the violence of civil war and economic dislocation led many to leave their homes, while family ties and social networks encouraged their journeys to lead north to the United States. More recently, Lundquist and Massey (Reference Lundquist and Massey2005) and Stinchcomb and Hershberg (Reference Stinchcomb and Hershberg2014) have provided further support for the idea that recent migration flows from Central America have been decidedly mixed in terms of the relative weight economic and political factors play in the decision (see also Reference Hiskey, Córdova, Orcés and MaloneHiskey et al. 2016; Reference Hiskey, Malone and OrcésHiskey, Malone, and Orcés 2014). Missing from this work, however, are systematic, individual-level analyses of the relative import that crime and violence play in the emigration decision. It is to this task that we now turn.

Modeling Emigration Intentions: Results from National Surveys

In order to explore the connection between crime victimization and emigration intentions, we analyze the probability that an individual has plans to emigrate as measured by the following question included in the 2014 AmericasBarometer surveys for Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras: “Do you have any intention of going to live or work in another country in the next three years?” Though clearly not a measure of actual emigration, an increasing number of scholars have found that an individual’s “emigration intentions” can offer a meaningful proxy for actual migration, particularly in traditional sending countries (e.g., Reference CreightonCreighton 2013; Reference RyoRyo 2013). Further, in standard models of emigration intentions, many of the most influential variables are highly consistent with those factors typically used to explain emigration itself, suggesting that while intentions do not always translate into action, the pool of potential emigrants likely includes most actual emigrants. It is also important to note that the primary destination for most Guatemalan, Salvadoran, and Honduran migrants is the United States. Unlike Nicaraguan migration patterns, where an estimated 45 percent go to neighboring Costa Rica, over 80 percent of all emigrants from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador reside in the United States.Footnote 10

In order to assess one’s direct experiences with crime, and the role such experiences play in one’s emigration plans, we rely on an item in the AmericasBarometer survey that asked respondents if they had been victimized by a crime in the previous twelve months. We then categorize respondents as (1) nonvictims; (2) those victimized once in the previous twelve months; and (3) those victimized more than once in the previous year. Figure 2 displays the emigration intentions of these three categories of respondents in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. From this simple descriptive figure, a fairly strong relationship emerges between crime victimization and a desire to emigrate, with a consistently lower percentage of respondents in the nonvictim category reporting emigration intentions compared to those in either of the other two victimization categories. Also, consistent with the DHS report mentioned earlier that highlighted the differences between Guatemalan migrants and those from El Salvador and Honduras, in these latter two countries we see a substantial increase in the percentage considering emigration as we move from the nonvictim category to those respondents victimized multiple times by crime. But the patterns in this figure must be treated with caution as they reveal only an apparent bivariate relationship between victimization and emigration plans. To determine more precisely what role crime victimization plays in pushing individuals to consider emigration, we turn now to a multivariate analysis of the determinants of emigration intentions.

Figure 2 Percentage with intentions to emigrate in the next three years. Authors’ estimations based on data from the 2014 AmericasBarometer Survey.

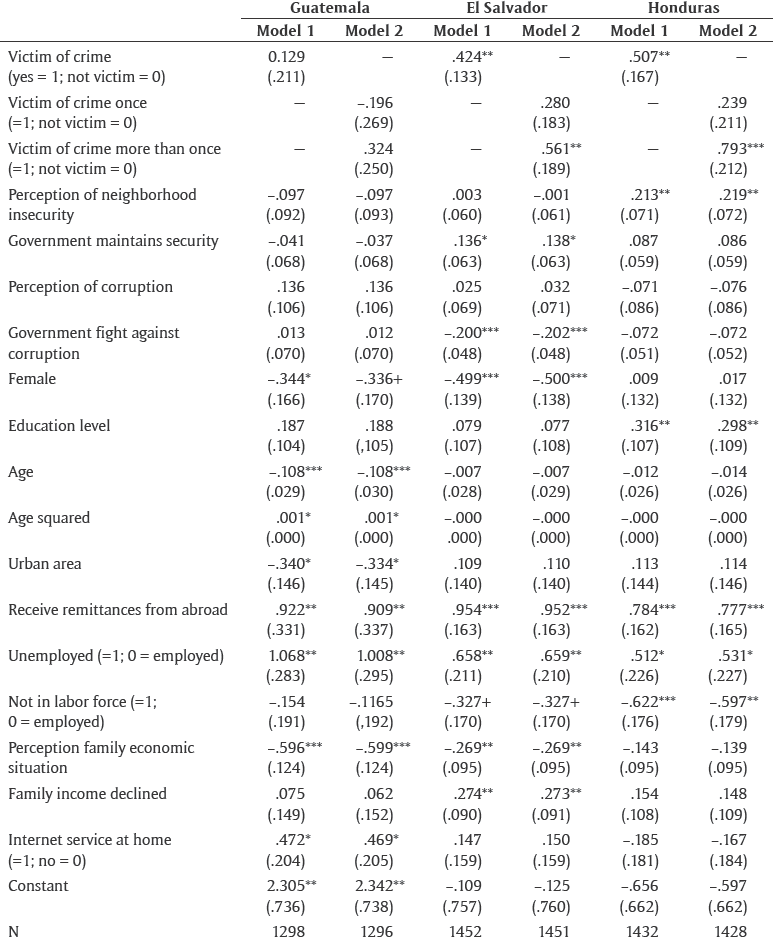

In order to control for other important factors associated with the emigration decision, we rely on an array of items in the AmericasBarometer survey. More specifically, our models of emigration intentions include controls for: (1) perceptions of personal security; (2) individual demographic characteristics; (3) cross-border connections with family members living abroad; (4) objective and subjective household economic conditions; and (5) perceptions of governance quality. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the measures we employ in the analyses below to capture these factors.Footnote 11

Table 1 Determinants of migration: Operationalization and measurement.

Our estimation strategy accounts for the functional form of our dependent variable and the fact that our empirical analyses are based on survey data. More specifically, since the variable on emigration intentions is binary, we estimate logit models and take into account the features of the sample design in the calculation of standard errors, namely clustering and stratification.Footnote 12 From the results displayed in Table 2, several items emerge to support the idea that crime victimization now plays a central role in the emigration decision of residents in Honduras and El Salvador. In Guatemala, by contrast, economic considerations remain a more important component in the emigration calculus than crime victimization.Footnote 13

Table 2 Emigration intentions in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.

+ p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Standard errors in parenthesis take into account the “design effect” due to clustering and stratification.

In the Guatemalan model, we see a profile of potential emigrants that is largely consistent with economic migration—young, unemployed males with migrant connections (receipt of remittances) who view their household economic situations as precarious at best. More importantly for our purposes, crime victimization does not emerge as a significant factor influencing the emigration plans of Guatemalan respondents. This null finding further supports the proposition put forth by the DHS report cited above that the nature of crime in Guatemala, as compared to that found in Honduras and El Salvador, is distinct, and that crime does not seem to play as important a role in the emigration decision of Guatemalans.

Conversely, Honduran emigration intentions appear more closely tied to problems of personal security rather than economic considerations. Neither gender nor age, two common identifiers of economic migrants, emerge as significant predictors of potential emigrants. Similarly, respondents’ views of their household economic situation do not have a significant influence on emigration plans. The one factor that does comport with standard accounts of migration is receipt of remittances, a measure we use to represent the depth of one’s connection to a migrant living abroad. Here it appears that regardless of whether one is driven by economic or security reasons to consider emigration, having a friend or relative sending remittances makes emigration a more viable life strategy. The clear overall message from these results, though, is that experiences with crime influenced Hondurans’ thinking about emigration far more in 2014 than any perceived economic opportunities awaiting them in the United States.

For the El Salvador model, we find mixed results in terms of the degree to which conventional factors associated with economic migration help predict Salvadoran emigration intentions. While age and education do not help predict emigration intentions among Salvadoran respondents, gender, receipt of remittances, and an individual’s economic circumstances and evaluations do conform with standard models of economic migrants. Here we find that males, remittance recipients, and those with negative views of the economy were more likely to report plans to emigrate than other respondents.

Most importantly, however, we again find that crime victimization is a powerful predictor of emigration intentions in El Salvador. Indeed, what most distinguishes both Hondurans and Salvadorans from their Guatemalan counterparts is the role that crime victimization plays in an individual’s consideration of emigration. Whereas victimization does not appear to influence the emigration calculus among Guatemalans, it is among the most important factors in predicting whether or not a Salvadoran or Honduran will report intentions to emigrate. Even more striking, when we include our categories of victimization as distinct variables in the models (Model 2 for each country), with nonvictims as the baseline category, we see that it is only those in the multiple victimization category that are significantly more likely to consider emigration. Thus, those suffering from crime and insecurity the most in Honduras and El Salvador are precisely those who are most likely to be making plans to leave.

Based on the results from Model 2 for each country, we estimate predicted probabilities to illustrate the substantive impact that multiple crime victimization has on emigration intentions in El Salvador and Honduras (see Figure 3).Footnote 14 In El Salvador, the probability of having emigration intentions is more than ten percentage points (10.5) higher for respondents victimized multiple times by crime than for those not victimized at all in the previous year. To evaluate this effect more closely, we perform a difference in mean predicted probabilities testFootnote 15 and again find that the difference between non-crime victims and those victimized multiple times is statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Figure 3 Mean predicted probability of emigration intentions by crime victimization. Results based on model 2 for each country in Table 2.

For Honduras, the effect of crime victimization is even more notable. The probability of intending to migrate increases from 30.8 to 46.3 percent as one moves from non-crime victims to those victimized multiple times, representing an increase of over 15 points. Again, the difference in means test also reveals that this effect is statistically significant at p < 0.001. Moreover, in the Honduras model, perceptions of neighborhood security also play a role in the emigration decision, suggesting the cumulative effect that crime and violence have on the decision calculus of those caught in the line of fire.

What these results highlight is that crime victimization played a far more important role in leading individuals from Honduras and El Salvador to consider emigration in 2014 than economic considerations. What we still do not know, but explore below, is whether the United States “send a message” campaign, which was in full effect in the summer of 2014, had any impact on this emigration decision. In the section that follows, we carry out further analyses for Honduras and find that the US deterrence strategy focused on communicating to potential migrants the possible risks of migration is not likely to be successful in the absence of effective strategies to address the real risks confronted by individuals living in these areas.

Do Deterrence Strategies Work? Evidence from Honduran Municipalities

In order to take this next step in our analysis, we now turn our lens toward understanding the emigration decision of individuals living in twelve municipalities in Honduras with varying levels of violent crime.Footnote 16 The survey was originally carried out by LAPOP to evaluate the programs of USAID in the areas where those municipalities are located. A total of 3,024 individuals were interviewed. A feature of the municipalities included in this survey is that they offer considerable variation in the percentage of respondents victimized by crime, as well as the aggregate municipal homicide rates. This variation allows us to examine intentions to migrate in municipalities like La Paz, with a comparatively low homicide rate of 8.6/100,000, to municipalities like San Nicolás, with a homicide rate of 260.2, providing further assurance that our results hold across a wide range of crime contexts.Footnote 17 To include this local crime context in our models, we control for the overall homicide rate in each municipality in the regression models.

It is also important to mention that, although significant variation exists in homicide rates, respondents interviewed in the twelve municipalities are on average more rural, have lower levels of education, and reported lower crime victimization rates than respondents in the national sample.Footnote 18 Therefore, data from this sample allow us to perform a more demanding test of the effect of crime victimization on migration intentions. If we continue to find that crime victimization significantly predicts migration intentions even in more rural contexts where crime tends to be less pervasive, the results would further support our contention that crime victimization is a powerful predictor of migration intentions—even if these individuals are aware of the risks associated with migration.

As noted above, LAPOP collected survey data in these twelve municipalities during late July and early August 2014. During the summer of 2014, the US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) launched the “Dangers Awareness Campaign,” a public information campaign across northern Central America that involved over six thousand public service announcements as well as hundreds of billboards (CBP 2014; GAO 2015). The campaign, announced by CBP Commissioner Kerlikowske on July 2, also included outreach efforts by churches, local governments, and non-government organizations in order to ensure that the campaign’s message reached all corners of the region. A similar campaign called the “Dangers of the Journey” had been tried in the spring of 2013 and the DHS found in an evaluation survey of this campaign that 72 percent of respondents (including both minors and adults) had seen the campaign and 43 percent recognized the campaign’s tagline (GAO 2015, 36). In August of 2015 the CBP began the “Know the Facts” campaign, following a very similar strategy to those employed in 2013 and 2014.

As the timing of the LAPOP Honduran special sample corresponded with both the “Dangers Awareness” campaign and a sharp increase in the number of Honduran migrants arriving at the US border, we added a series of questions to gauge respondents’ perceptions of US immigration policy and the perceived risks of immigration to the United States. We utilize these data to test the impact these perceptions of US immigration policy may have had on respondents’ intentions to migrate. The items were worded as follows:

“Taking into account what you have heard about undocumented migration, do you think crossing the U.S. border is easier, more difficult, or the same as it was 12 months ago?

“Taking into account what you have heard about undocumented migration, do you think crossing the U.S. border is safer, less safe, or the same as it was 12 months ago?

“Now, keeping in mind what you have heard about Central American migrants in the United States, do you think [they] are being treated better, the same, or worse than 12 months ago?

“Do you think that deportations in the United States have increased, stayed the same, or decreased in comparison to 12 months ago?”

Figure 4 displays the extent to which these Honduran respondents were aware of the heightened risks of making the journey to the United States and the greater chance of deportation migrants faced upon arriving in the United States relative to the previous year. From these results we see a high degree of consensus among respondents that the trip to the United States was more difficult, less safe, and one with a higher probability of deportation and worse treatment of migrants within the United States than in the previous year.Footnote 19 It appears, then, that the “Dangers Awareness” message succeeded in convincing Hondurans that migration to the United States in August 2014 was a highly dangerous proposition with little chance of success. If the underlying assumption of the US “send a message” policy is correct, all else equal, we should see those respondents who were aware of the heightened dangers in the summer of 2014 less likely to express intentions to leave their country than their counterparts who were unaware of the increased dangers and enhanced deterrence efforts on the part of US officials.

Figure 4 Awareness of heightened risks of emigration (percentage of respondents). Authors’ estimations based on data from the 2014 LAPOP Survey in Honduran Municipalities.

In order to evaluate the impact that perceptions about the US immigration context may have had on emigration intentions, we first replicate the model we analyzed in the previous section. Columns 1 and 2 of Table 3 report the results from these first models. Several points of comparison with the results from the Honduran national sample warrant attention. First, as Model 1 shows, crime victimization continues to play a significant role in shaping the emigration intentions of respondents. Furthermore, when we categorize crime victims based on the frequency of victimization, the “multiple victimization” category again emerges as one of the strongest predictors of emigration intentions in the model (see Model 2). Overall, these results reinforce our contention that for those migrants who did arrive at the US border in the summer of 2014 and later, escape from crime and violence seems to have been their primary motivation.

Table 3 Emigration intentions in selected Honduran municipalities.

+ p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Standard errors in parenthesis take into account the “design effect” due to clustering and stratification.

In contrast to the national-level analysis, however, those respondents considering emigration in these selected municipalities also share some characteristics of more traditional migrants. Males are more likely to be potential emigrants than their female counterparts, as are those respondents who reported a decline in household income. We also see that remittance recipients are more likely to report emigration intentions than those respondents who do not receive remittances. Despite the significance of these control variables, though, the overwhelming motivating factor for emigration among these respondents is their direct experiences with the crime and violence prevalent in many of these communities.

In order to determine the extent to which views of the US immigration climate have on emigration plans, we incorporate into Models 3 and 4 in Table 3 responses to the four US immigration context items listed above. Here the finding of most import is a null finding—none of these “perceptions of U.S. immigration” variables matter at all in terms of predicting one’s emigration intentions.Footnote 20 Simply put, respondents’ views of the dangers of migration to the United States, or the likelihood of deportation, do not seem to influence their emigration plans in any meaningful way.Footnote 21 Further, the inclusion of these variables in the model does little to change what continues to be the most consistent predictor of emigration intentions: crime victimization.

As evident in Figure 5, the effect of crime victimization on emigration intentions is considerable even after controlling for respondents’ views toward the US immigration context. For nonvictims, even those living in high-crime contexts, the probability of having emigration intentions is 19.5 percent. For a multiple crime victim, however, that probability jumps to 37.6 percent. Not surprisingly, this difference in the probability of reporting intentions to emigrate for nonvictims and multiple victims is statistically significant at p < 0.001.Footnote 22

Figure 5 Mean predicted probability of emigration intentions in selected municipalities in Honduras. Results based on model 4 in Table 3.

What these results demonstrate, once again, is that our multiple crime victimization category goes a long way in identifying those Hondurans for whom the country’s wave of crime and violence has truly become a refugee-like situation. Being victimized by crime multiple times within a single year clearly emerges as decisive in pushing respondents to consider emigration as a viable life option.

The role of crime victimization in an individual’s migration calculus, and the utter lack of statistical significance of the US immigration context items, calls into question the basic assumption on which the US “send a message” campaign has rested: that if only those considering emigration from Central America knew the risks and low chances of success they would decide to stay home. What our results clearly demonstrate is that perceptions of the US immigration climate have no significant impact on the emigration decision, at least among Hondurans. The powerful effect that crime victimization has on one’s willingness to consider emigration suggests that Hondurans are far more driven by a desire to “leave the devil they know” than they are dissuaded to leave by the possible risks that may await them.

Conclusion

We find that the violence characterizing the present-day reality of many citizens of Honduras and El Salvador exerts a powerful influence on their emigration calculus. In particular, those individuals suffering multiple incidents of crime victimization within a year emerge in our analysis as those most likely to flee the more generalized violence of El Salvador and Honduras. This finding echoes those of a recent qualitative report on Central American migrants that it is “specific acts of violence, rather than the generalized violence … [that] precipitated flight in search of protection” (Center for Migration Studies and Cristosal 2017, 1). The desire to flee from violence appears to overshadow considerations about any future risks they might face if they flee that reality. These findings raise questions about the effectiveness of current US efforts to deter future emigration from countries with high levels of crime and violence. The detention and deportation of current migrants from El Salvador and Honduras, along with the extensive publicity of these detention and deportation proceedings, is unlikely to persuade many of the individuals in these countries who are directly experiencing the tragically high levels of crime and violence.

It is understandable that US policymakers have sought to deter migration by relying on a strategy of border enforcement, migrant detention, expedited deportation, and, most recently, high-profile ICE raids and talk of border walls. In many ways, this approach is easier for policymakers to sell to their constituents, offers a more concrete payoff in terms of demonstrable increases in individuals detained and/or deported, and has an intuitive appeal for those unfamiliar with life in a high-violence context. Further, just as with the Reagan administration’s steadfast denial throughout the 1980s that individuals fleeing civil war in countries like El Salvador qualified as refugees, there appears today a similar reticence among US policymakers to acknowledge the war-like conditions from which many Central Americans are fleeing. So it is no surprise that the “send a message” policy option continues to dominate much of the rhetoric surrounding the immigration issue more generally.

That appeal rests on the idea that if individuals living in these contexts can just be convinced that emigration is a riskier alternative than staying home then they will decide to stay. Unfortunately, however, understanding why policymakers in the United States are likely to opt for a strategy of deterrence based on detention and deportation does not make it an effective strategy. What our results point to is the inability of this approach to dissuade that subset of individuals who have directly experienced the cruelties of life in a high-crime context from taking a life-threatening chance to escape that reality.

The consequences of pursuing a get tough, “send a message” policy approach are many. First, it is now a well-established finding among migration scholars that efforts to increase border security, whether by building a longer and higher wall or further militarizing the border, have a limited deterrence effect on those seeking to enter a particular destination country (e.g., Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouacouci, Pellegrino and TaylorMassey et al. 1998; Reference Slack, Martinez, Whiteford and PeifferSlack et al. 2015). Rather, border walls and militarization tend to increase the chances that migrants currently in the destination country will remain there rather than return home (Reference Massey, Durand and MaloneMassey, Durand, and Malone 2002).

Second, if it is the case that a “regime of deterrence” (Reference HamlinHamlin 2012, 33) serves only to dissuade individuals with primarily economic motivations for migration, many of those that do continue to arrive at the border from Honduras and El Salvador will be even more likely to be precisely those with the most legitimate claims for asylum. In this context, the notion of a continued emphasis on expedited removal, particularly for this vulnerable population, would seem to fly in the face of US commitments to domestic and international legal norms with respect to basic standards of treatment for refugees. The fact that the United States has a long history of selective adherence to these commitments, particularly with respect to those fleeing conflicts in Central America (e.g., Reference HamlinHamlin 2014, Reference Hamlin2012; Reference StanleyStanley 1987), should not serve as a reason to renege on these commitments yet again.

Third, regardless of the effect this “send a message” campaign may have on future migration flows, the most pressing problem that the recent focus on detention and deportation has highlighted is the woeful lack of resources available to the US immigration court system. Though the immigration case backlog and significantly understaffed immigration judiciary have been clear for at least a decade, the surge in Central American women and children border arrivals in recent years has brought the system to the brink of apparent collapse. The number of pending immigration cases has nearly quadrupled since the early 2000s, now standing at 542,000 according to data gathered by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). As a consequence, the average wait time for a case to be heard is more than double what it was in 1998, standing at 677 days in 2016 (TRAC 2017).

That such delays and backlogs exist should be no surprise given the disparity in funding between US border enforcement efforts and the country’s immigration court system. In 2014, CBP and ICE received an estimated $18 billion, while the immigration court system, known formally as the Executive Office of Immigration Review, received $312 million for the same year (Reference Fitz and WolginFitz and Wolgin 2014). A reflection of this funding disparity emerges from a comparison of increases in the number of immigration judges and the number of CBP agents since the early 2000s. For the former, the number moved from 215 judges in 2003 to 258 in 2012. The number of CBP agents, meanwhile, nearly doubled during the same time period, moving from 10,819 in 2003 to 21,394 in 2012 (Reference Fitz and WolginFitz and Wolgin 2014). In sum, rather than continuing efforts to “send a message” aimed at deterrence, fixing the US immigration court system may be a far more effective way to at least begin to manage recent Central American migration flows and maintain at least some measure of adherence to United States and international legal norms with respect to the treatment of those seeking asylum.

Despite the current administration’s apparent embrace of the deterrence strategy that has long guided US policy toward Central American migrants, there do appear to be elements within the DHS that recognize the need for a more nuanced policy response to the current situation. In addition to efforts during the summer of 2016 to expand the scope of the Central American Minors program and continue implementation of in-country screening of asylum claims, an agreement was reached with the government of Costa Rica to enlist that country in the protection of refugees fleeing Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras (CBP 2016). All of these efforts appear to be driven by the 2016 increase in US border apprehensions of Central Americans after a 2015 decline. As the CBP stated in a summer 2016 press release, the agency does “recognize the need to provide a safe, alternative path to our country for individuals in need of humanitarian protection” (CBP 2016).

Such a recognition suggests that there is at least some impetus to change the view of many US policymakers that all US southwest border arrivals are motivated by economic considerations, and thus can be easily dissuaded from making such a journey with the right message of deterrence. Whether these initial signs of change will continue is unclear, but evidence that migration flows from these countries are driven as much, if not more, by violence than they are by economics is abundantly clear. We share the view expressed in a recent report by the Center for Migration Studies that “the use of deterrence policies only exacerbates the suffering” of those arriving from the northern region of Central America and “ultimately these policies will fail, as the threats confronting [them] will remain stronger than the risk of fleeing” (CSM and Cristosal 2017, 51). If the United States aims to reduce the number of people seeking to “leave the devil they know,” it must invest more seriously in making that devil less menacing, rather than trying to send a message of how much more menacing an attempt to enter the United States might be.

Additional Files

The additional files for this article can be found as follows:

Table A1. Types of Victimization by Country (2014). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A2. Descriptive Statistics: Guatemala, 2014 National Sample. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A3. Descriptive Statistics: El Salvador, 2014 National Sample. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A4. Descriptive Statistics: Honduras, 2014 National Sample. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A5. Descriptive Statistics: Honduras, 2014 Municipal Sample. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A6. Odds Ratios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A7. Emigration Intentions in Selected Honduran Municipalities (Odd Ratios). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A8. Emigration Intentions in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras (Maximum Likelihood estimation, 2014 National Samples). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A9. Emigration Intentions in Selected Honduran Municipalities (Maximum Likelihood estimation). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A10. Goodness of Fit Test (based on models estimated using Taylor Series Linearization, 2014 National Samples). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A11. Goodness of Fit Test (based on models estimated using Taylor Series Linearization, 2014 Municipal Sample). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A12. Goodness of Fit Statistics (Maximum Likelihood estimation, 2014 National Samples). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A13. Goodness of Fit Statistics (Maximum Likelihood estimation, Municipal Sample for Honduras). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A14. Crime Rates in Selected Honduran Municipalities (2014). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A15. Correlation Table (Honduran Selected Municipalities Sample). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A16. Emigration Intentions in Selected Honduran Municipalities (Checking for Multicollinearity). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1

Table A17. Emigration Intentions in Selected Honduran Municipalities (Checking for Multicollinearity). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.147.s1