Every sexual encounter (i.e., vaginal penetration with a penis, regardless of whether ejaculation occurs) carries a risk of an unplanned pregnancy unless contraception is used. Women make decisions about contraception throughout their reproductive life, from first sexual activity, through the child-bearing years and then into the perimenopause until the menopause. Some women may quickly find a method that suits them, whereas others will need to try different methods – and may never be truly satisfied. The Contraceptive Counselling (COCO) study of over 1,000 women found that only one-third were very satisfied with their current contraception. One-third were satisfied but wanted to consider a different method, and another third were somewhat satisfied, but felt there might be a more suitable method for them.

It is important that women feel empowered to discuss the full range of contraceptive options with healthcare professionals. This discussion should include the benefits, including non-contraceptive benefits, risks and side effects associated with different methods. It is also important to reconsider contraceptive methods at different stages of life, as needs change and new medical conditions or medication may affect options.

Decisions about the type of contraception to use can be influenced by many factors (Box 1).

Box 1 Factors that influence decisions about contraception

Sources of information – from healthcare professionals, leaflets, the internet, social media, word of mouth (e.g., family and friends)

How well methods work (effectiveness) and how much this depends on the user

Family planning – is pregnancy planned in the near future?

Medical history and suitability of different methods

Implications of pregnancy – how important is it to avoid pregnancy?

Lifestyle factors

Sexual activity

Alcohol or illicit drug taking and how this may affect correct use of certain methods of contraception

Is it practical to take a tablet daily? Is it easy to remember?

Menstrual cycle – would there be benefit in regulating or reducing bleeding? (see Chapter 9)

Additional benefits, such as treating the symptoms of endometriosis or the perimenopause (see Chapter 9)

This chapter considers issues that may influence decisions about contraception at different stages of life. The later chapters describe the different methods in detail.

The right method of contraception can contribute to overall well-being by:

supporting an active sex life whilst reducing concerns about unplanned pregnancy

preventing transmission of sexually transmitted infections (condoms)

reducing problems associated with periods (e.g., heavy or painful periods)

being able to plan when to conceive (for personal reasons or because of a pre-existing medical condition)

planning intervals between pregnancies.

Accessing Information

Information about contraception can be obtained from many sources: healthcare professionals, patient information leaflets, friends, family, the internet and sex education lessons at school. Use of contraception may be influenced by personal factors such as knowledge and understanding about conception and different methods of contraception, attitudes, perceived risk, family structure and relationships, socioeconomic status, peer influences and access to services.

Knowledge of different methods is important, and choices may be influenced by factors such as effectiveness (how well it works) – and how much this depends on the user – possible side effects, ease of use and how ‘invasive’ a method is thought to be. Some women may be motivated to take the contraceptive pill reliably every day whereas others may prefer a ‘fit and forget’ method of contraception, such as the progestogen-only implant or the coil.

Unfortunately, not all sources of information are reliable. However, the wrong information, once accepted, can be difficult to redress – this is what we mean by myths. Many of the myths and misunderstandings relating to contraception are addressed in the individual chapters that follow.

A contraceptive consultation offers a range of additional healthcare benefits, such as screening for sexually transmitted infections (including HIV), vaccinations, cervical screening, health promotion (e.g., help with smoking cessation; management of substance misuse) and support with social issues (e.g., intimate partner violence).

Fertility

In the absence of contraception, the risk of pregnancy depends on the fertility of both partners; the length, regularity and variability of the menstrual cycle; and the timing and frequency of sex.

Fertility is affected by many factors including age, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle factors, such as smoking, and weight. Steps can be taken to improve fertility and the chances of conception; however, irrespective of an individual’s medical history, contraception is required by any woman of reproductive age who wants to prevent pregnancy.

Men or women may believe that they are ‘infertile’ or unlikely to conceive, perhaps because of a medical condition, hormone treatment or because they have not successfully conceived. Nevertheless, even if the risk of conception seems minimal, contraception is important if pregnancy is to be prevented.

Family Planning

Contraception enables individuals and couples to plan when to have a family alongside other life goals such as family commitments, travel, education, a career and achieving financial security. Women are increasingly delaying conception until later in life to achieve an education and career goals before having children. Women also have the opportunity to optimise their health before pregnancy, ensuring good blood-sugar control, weight management and smoking cessation, for example.

Contraception also helps women to plan the interval between pregnancies – for personal as well as health reasons. The World Health Organization recommends a 24-month interval between children. A gap of less than 12 months can be associated with an increased risk of complications, such as preterm labour, stillbirth, low-birth-weight babies and neonatal death.

Other than sterilisation, the use of contraception does not generally compromise longer-term fertility. Fertility returns immediately after stopping contraception with most methods, giving women the flexibility to plan a family. The exception is the progestogen-only injection; fertility usually returns within 6 months, but this can take up to 12 months.

Culture and Trends in Contraception

Contraceptive choice is influenced by a multitude of factors, including cultural issues, education, social and economic factors, religion, fashion and trends. Individual beliefs and ideas about different methods play a large part in method choice.

Women have access to a wide breadth of information and opinions via the internet and social media and increasingly discuss matters with friends and family or via online forums. However, there is a lot of misinformation on social media, including individual ‘horror stories’ and vocal opinions that may sway individuals. It is important to check that information is from a reputable source, such as the National Health Service in the UK, rather than relying on one individual’s experience or agenda – people are quick to report bad experiences but are generally less vocal about good experiences.

It is also important to be aware that pharmaceutical products and devices cannot legally be promoted directly to the consumer in the UK, whereas apps, including natural family planning apps, are not regulated in this way.

Religion and Culture

Organised religions include teaching on sexuality and family formation as fundamental human behaviours and may give guidance on the morality and ethics of sex within and outside of marriage, contraception and abortion, all of which may influence an individual’s and couples’ attitudes, choices and behaviours. Cultural factors may also influence decisions about family size and when it is acceptable or appropriate to conceive.

Trends

The advent of the contraceptive pill in the 1960s provided women with greater control over their reproductive choices, and had a key role in changing sexual attitudes and freedom; however, the popularity of this method appears to have changed over time in favour of other methods of contraception. These include long-acting reversible contraception – the implant, injection and coil. Natural family planning has received a lot of attention, particularly on social media, portrayed as a ‘healthy, natural option’; however, the complexity of this method is usually played down, including the commitment required for success (see Chapter 7). Younger women in particular may be more likely to be influenced by promotional information. However, women are at their most fertile during the early years of their reproductive life, and a more reliable contraceptive method is required to prevent pregnancy.

A contraceptive counselling appointment with a specialist in sexual health or general practice can be helpful to understand the range of options available and to support informed decisions.

When Is Contraception Needed?

Anyone with ovaries and a uterus who has sex with someone with testicles and a penis and who does not want to become pregnant requires contraception, throughout reproductive life (from their first sexual encounter to the menopause). This includes trans-men and non-binary people, even if they are taking masculinising hormones. Sexual activity and contraceptive needs will vary throughout life. For example, a sexually active teenager or young adult may want to avoid pregnancy at all costs, whereas a woman in a stable relationship who is considering having children may be less concerned by an unplanned pregnancy. The imperative not to conceive may increase again later in life, particularly during the perimenopause and once a woman considers that her family is complete.

Many women believe that they cannot conceive if they do not have periods or if their periods are irregular; however, this is not true! Women may still ovulate even if they do not have periods – and the fertile window occurs within 6 days of ovulation. Infrequent ovulation is associated with irregular menstrual bleeding, which can make predicting fertility almost impossible, and a random period may be the first warning that ovulation has already occurred. So, if a pregnancy is not desired, use contraception!

Some women may be advised against pregnancy because of a medical condition, and women and men who are taking certain medications that could harm a developing fetus will be advised to choose an effective method of contraception (ideally one that does not rely on the user) to minimise the risk of an unplanned pregnancy. For women with medical disorders and couples where either partner takes medication that could affect a developing baby, pregnancy should be planned in discussion with their doctors.

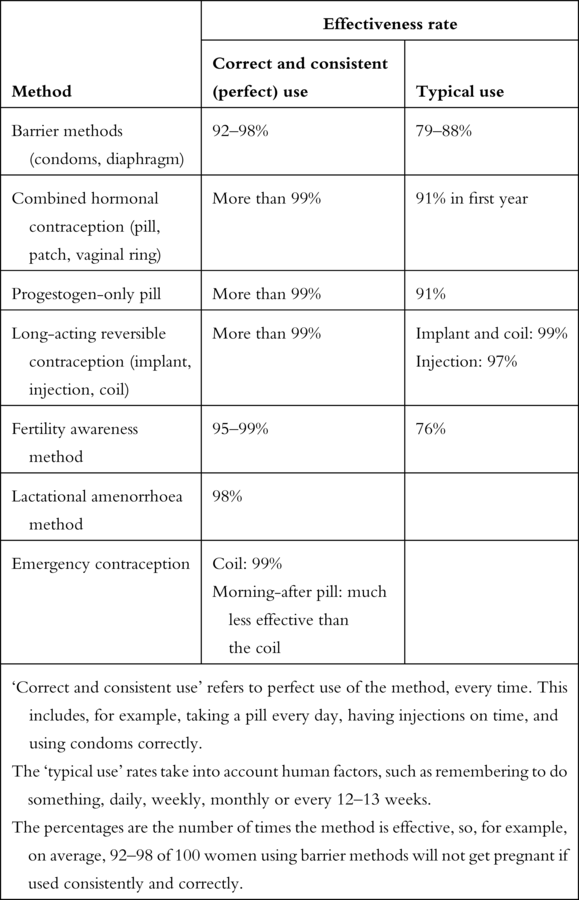

Effectiveness of Contraception and Dependence on the User

No method of contraception is 100% guaranteed to prevent pregnancy, but most methods are effective more than 99% of the time. This means that pregnancy is, on average, avoided 99 times out of a 100. Another way to describe this is a failure rate of less than 1% (i.e., no more than one pregnancy among 100 women using the particular method of contraception).

In this book we refer to effectiveness rates for each method of contraception:

‘Correct and consistent use’ refers to perfect use of the method, every time. This includes, for example, taking a pill every day, having injections on time, and using condoms correctly.

The ‘typical use’ rates take into account human factors, such as remembering to do something, daily, weekly, monthly or every 12–13 weeks.

Effectiveness rates are higher with correct and consistent perfect use than with typical use, as shown in Table 1. The difference is greater for methods that are highly dependent on the user, such as the pill or condom, and lower for ‘fit and forget’ methods such as the long-acting reversible contraceptive methods.

| Method | Effectiveness rate | |

|---|---|---|

| Correct and consistent (perfect) use | Typical use | |

| Barrier methods (condoms, diaphragm) | 92–98% | 79–88% |

| Combined hormonal contraception (pill, patch, vaginal ring) | More than 99% | 91% in first year |

| Progestogen-only pill | More than 99% | 91% |

| Long-acting reversible contraception (implant, injection, coil) | More than 99% | Implant and coil: 99% Injection: 97% |

| Fertility awareness method | 95–99% | 76% |

| Lactational amenorrhoea method | 98% | |

| Emergency contraception | Coil: 99% Morning-after pill: much less effective than the coil | |

‘Correct and consistent use’ refers to perfect use of the method, every time. This includes, for example, taking a pill every day, having injections on time, and using condoms correctly. The ‘typical use’ rates take into account human factors, such as remembering to do something, daily, weekly, monthly or every 12–13 weeks. The percentages are the number of times the method is effective, so, for example, on average, 92–98 of 100 women using barrier methods will not get pregnant if used consistently and correctly. | ||

How Do I Choose a Method?

Several factors are important when deciding which form of contraception is most appropriate at a particular stage of life. The questions in Box 2 can be helpful in discussions with a doctor, nurse or pharmacist. Options for contraception at different stages of life are discussed towards the end of this chapter.

Box 2 Questions regarding the most appropriate form of contraception at particular stages of life

How important is it for you to avoid pregnancy at this stage in your life?

How soon might you want to become pregnant? (e.g., starting or adding to your family)

How satisfied are you with your current method (if you are using one)? Do you experience any problems?

How likely are you to use a contraceptive method as intended? (e.g., how likely are you to take a pill every day?)

What do you want to happen to your periods?

Do you have any medical issues to consider?

Are you taking any other medications?

Is protection against sexually transmitted infections important?

Contraception for Transgender and Non-binary People

Anyone with ovaries and a uterus who has vaginal sex with someone who has a penis and testicles has the potential to conceive and should therefore use contraception to avoid an unplanned pregnancy.

Non-binary and transgender people often face challenges when discussing contraception with healthcare professionals. However, more sexual health services are providing specialist clinics, and healthcare professionals are better trained to help. When discussing contraception, it is particularly important to consider current status in terms of hormone use and planned or completed surgery together with any potential risk of sexually transmitted infections. Transgender and non-binary people assigned female at birth (AFAB) may take testosterone therapy or gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. Whilst these suppress ovarian function, they do not provide reliable contraceptive cover. It is also important to be aware that pregnancy must be avoided during testosterone therapy to reduce harm to a developing female fetus.

For AFAB people:

Progestogen-only methods are not thought to interfere with hormone treatments and have the additional benefit of reducing or stopping vaginal bleeding (these are described in Chapters 5 and 6).

Long-acting reversible contraception is a good option; the coil that contains the progestogen levonorgestrel may be preferred over the copper coil because they reduce bleeding (these are described in Chapter 6).

The combined hormonal contraceptive choices (the pill, patch and vaginal ring) are not recommended because the estrogen component may counteract the masculinising effects of testosterone.

Hormone treatments used by transgender and non-binary people assigned male at birth (AMAB), such as estradiol, GnRH analogues, finasteride and cyproterone acetate, reduce but do not inhibit sperm production so contraception is vital if having penetrative vaginal sex.

Sterilisation of either partner is also an option.

Emergency contraception (both oral methods and the copper coil; see Chapter 8) can also be used safely and is not thought to interfere with hormones used by transgender and non-binary people.

A Lifetime of Contraception: From Teenage Years to the Menopause

In this section we discuss how contraceptive needs and decisions may change through a woman’s life. Experience demonstrates that women tend to stay with one method of contraception that works for them, and they may not be aware of the wide range of options available, some of which may be more suitable at different life stages.

For this section we have chosen four groups to illustrate the different life stages when the need for contraception and the attitude to a pregnancy may vary:

young(er) women who are likely to have a strong desire to avoid pregnancy

women who are ready to plan a family

women over 40 who do not want to have children, but have yet to reach the menopause

perimenopausal women.

To make our descriptions easier, we have made some assumptions about women’s sexual activity and desire (or not) for pregnancy; however, each person has individual contraceptive needs. When choosing a method of contraception, it is more important to consider the woman’s needs, potential benefits, risks and side effects, as well as their attitude to any risk of pregnancy, rather than focusing on age or stage of life. Attitudes to contraception at each stage of life may change over time.

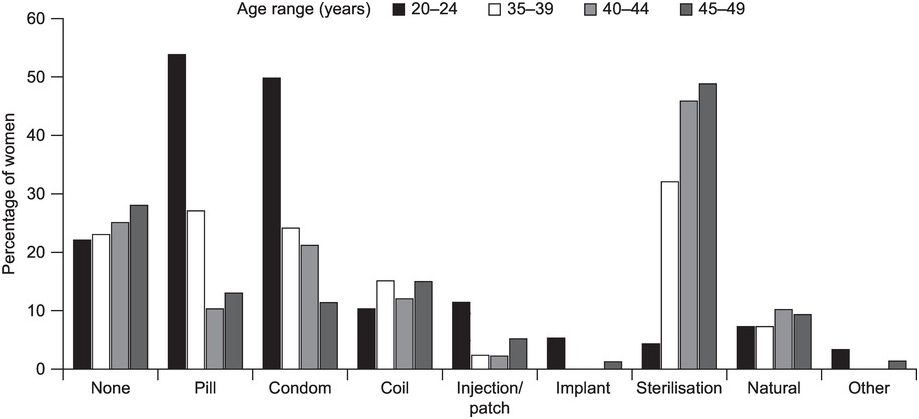

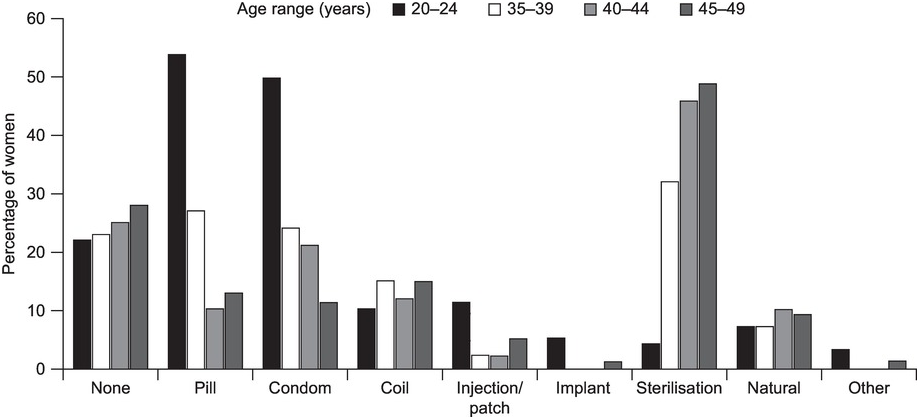

Figure 6 shows how the use of contraception changes with age, based on a survey undertaken in 2009: oral contraception and external condoms are more widely used by younger women, whereas longer-acting methods are more commonly used by older women. However, as discussed below, long-acting reversible methods of contraception may be ideal for sexually active younger women, and use of these is increasing. Many young women are not aware that these are potentially good options.

Figure 6 Use of contraceptive methods by women of different age groups. The number of women using long-acting reversible contraception is quite low, despite the benefits. About one-fifth of women of all ages do not use any contraception. Based on data from the Office of National Statistics’ 2009 survey on contraception and sexual health.

Younger Women

Younger women are more fertile and are at high risk of pregnancy from their first sexual encounter, including before their first period, as ovulation may start before menstruation.

Younger women need support to understand the full range of contraceptive choice, and to feel informed and confident when discussing their contraceptive needs. Sexual health clinicians and most primary care practitioners are comfortable discussing sex, contraception and other personal matters, without being judgemental. Teenagers are likely to be prioritised for appointments in either setting. Confidentiality is ensured (unless sexual abuse, exploitation or terrorism is suspected).

Whilst short-acting contraceptive methods are popular (the pill, the patch or the vaginal ring), their effectiveness depends on the user. The long-acting reversible contraceptive methods may be more suitable for women who want to be sexually active without worrying about an unplanned pregnancy. In order of effectiveness, these are the progestogen-only implant, coil and injection. The long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (the implant, injection, coil) are increasingly being used by this age group; the implant is particularly popular and accepted as the cultural norm.

Women Ready to Start a Family

Women who are ready to start or plan a family have different contraceptive requirements from younger women and they may prefer a method that can be discontinued without medical intervention. However, even with long-acting reversible contraception fertility returns immediately after stopping use (with the exception of the progestogen-only contraceptive injection – it can take 6–12 months for fertility to resume).

Fertility returns 21 days after childbirth, and it is possible for a woman to become pregnant before her first period (ovulation occurs before a period). Women vary in how soon they are ready to have sex after giving birth, but about 50% resume sexual activity within 6 weeks, and many unplanned pregnancies occur during this time. Women are advised to avoid pregnancy for 12–18 months after giving birth, to allow their body to recover and to reduce any risks during the next pregnancy.

It is important to consider postnatal contraception before giving birth and ideally to decide on a method during this time. Waiting until the postnatal check-up at 6–8 weeks is often too late! All the current methods of contraception are suitable following delivery, although the timing differs between methods.

Emergency hormonal contraception (the ‘morning-after pill’) can be used in the event of unprotected sex from 21 days after childbirth, but the coil can only be fitted after 28 days (see Chapter 6).

Breastfeeding suppresses ovulation and can therefore provide effective contraception (98%) for up to 6 months, as long as the baby is exclusively breastfeeding throughout the day and night and the mother’s periods have not started again. This is known as the ‘lactational amenorrhoea method’ and is described in Chapter 7. The copper in the coil does not affect breastmilk production or quality. Combined hormonal contraception should be avoided in the first 6 weeks following delivery in women who are breastfeeding. Low levels of hormones are excreted in breastmilk and would not harm a baby.

Women over 40

Fertility declines with age, particularly from the mid to late 30s, and pregnancy is rare after 50 years of age. However, the number of women having terminations in their 40s is increasing, possibly because of misunderstanding over pregnancy risk. Contraception is needed until the menopause (see the next subsection) to prevent an unplanned pregnancy.

Decisions by women in this age group may be influenced by similar factors as in younger women, such as motivation to take a pill every day or the desire for a more discrete form of contraception. Long-acting reversible contraception is popular in this age group, but the specific contraceptive choice may be influenced by age-related health conditions, such as heart disease, female-specific cancers, bone health and perimenopausal symptoms (see Table 2).

| Progestogen-only injection | Risks and benefits should be reviewed regularly in women over 40 A different form of contraception is advised beyond age 50 because of potential effects on bone health |

| Combined hormonal contraception | Combined pills that contain no more than 30 μg ethinylestradiol are preferred for women over 40 years, because of the potentially lower risk for blood clots, cardiovascular disease and stroke Combined pills containing levonorgestrel or norethisterone as the progestogen component are preferred over other formulations because of a potentially lower risk of blood clots An estrogen-free method should be used beyond age 50 The combined pill reduces the risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer; this benefit continues for several decades after discontinuation of the method There is a slight increase in the risk of breast cancer in women using the combined pill although the absolute rate is very low; there is no significant risk of breast cancer 10 years after stopping treatment Women aged 40–50 years can use continuous combined hormonal contraception Restarting the combined pill after a break increases the risk of blood clots, so women should not repeatedly interrupt this method of contraception Women who smoke should stop combined hormonal contraception at 35 years, when the mortality risk associated with smoking starts to become clinically significant |

Barrier methods can be a good option in this age group because declining fertility reduces the risk of pregnancy; however, these methods are user dependent, and effectiveness can be influenced by conditions more common in this age group, such as vaginal prolapse and erectile dysfunction. Natural family planning becomes less reliable as women approach the menopause and, as cycles become less regular, it is increasingly difficult to predict ovulation and the fertile window.

Women may consider sterilisation once their family is complete. However, many methods of contraception are more effective than sterilisation, including the progestogen-only implant and coil, without the risk associated with surgery. Combined hormonal contraception can also potentially help with common gynaecological symptoms such as heavy periods.

Combined hormonal contraception (the pill, patch, vaginal ring) may be appropriate, depending on the individual woman’s risk factors, and may help with symptoms of the perimenopause. The vaginal ring may cause an increase in vaginal secretions, which may be a welcome side effect as vaginal dryness can be a problem during the perimenopause! Hormonal contraception that does not contain estrogen does not improve symptoms of the perimenopause such as hot flushes, night sweats and difficulty sleeping.

Some age-related health conditions may influence the choice of hormonal contraception (Table 2). There are no specific health-related concerns with the progestogen-only implant, progestogen-only pill and the coil.

Perimenopause

The perimenopause refers to the years leading up to the menopause, which is defined as 12 months after a woman’s last period. During the perimenopause, estrogen levels can fluctuate widely, and menstrual patterns often become erratic. Ovulation no longer happens regularly and bleeding may be unpredictable, heavier and last longer – although in some women periods can stop suddenly. Hormonal fluctuations experienced at this time can result in a wide range of perimenopausal symptoms. Hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbance and mood swings are well-known symptoms, but anxiety, brain fog and joint and muscle aches and pains are less well recognised.

Women aged 50 and older are advised to use contraception for 12 months after their last period (24 months for women under age 50). Women who are using hormonal contraception may not be able to identify when their periods stop and should therefore consider using contraception until 55 years of age. Contraception is no longer needed from age 55 years, as spontaneous conception after this age is exceptionally rare, even in women who still have periods.

Combined hormonal contraception can help to manage perimenopausal symptoms, by masking symptoms associated with low and fluctuating estrogen levels. However, other health conditions need to be considered when prescribing this type of contraception, particularly in older women. It should be remembered that most hormone-replacement therapy (HRT) does not provide reliable contraception. A 52-mg-progestogen-containing coil can be used for contraception in women of this age group whilst also providing the progestogen component of HRT (the estrogen component is provided as a pill, patch, gel, spray or implant). If inserted after age 45, the progestogen-containing coil can be left in place until 55 years of age to provide contraception (i.e., for up to 10 years), but it should be changed every 5 years when used as the progestogen component of HRT. The copper coil can remain in place until after the menopause if inserted at age 40 or older.

Summary

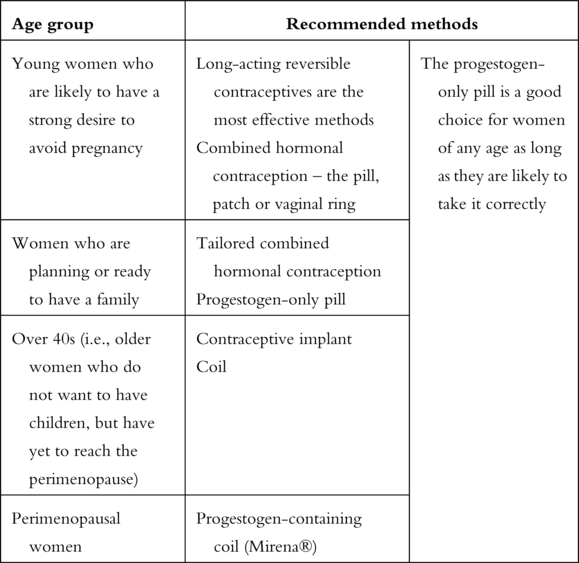

Table 3 summarises the recommended contraceptive methods for each life stage, based on our personal clinical experience. Note that most contraceptive methods are suitable for most women.

Table 3 The authors’ recommended contraceptive methods at different stages of life

| Age group | Recommended methods | |

|---|---|---|

| Young women who are likely to have a strong desire to avoid pregnancy | Long-acting reversible contraceptives are the most effective methods Combined hormonal contraception – the pill, patch or vaginal ring | The progestogen-only pill is a good choice for women of any age as long as they are likely to take it correctly |

| Women who are planning or ready to have a family | Tailored combined hormonal contraception Progestogen-only pill | |

| Over 40s (i.e., older women who do not want to have children, but have yet to reach the perimenopause) | Contraceptive implant Coil | |

| Perimenopausal women | Progestogen-containing coil (Mirena®) | |

Switching Contraception

Many women find that they need or want to swap to a different form of contraception at different stages in their life – either because their current method is not optimal or because their reasons for using contraception or desire for pregnancy have changed.

It is important to plan the switch to a different type of contraception carefully in order to avoid an unplanned pregnancy. For example, sperm can survive in the fallopian tubes for up to 7 days, so there is a risk of fertilisation if the coil is removed within 7 days of unprotected sex. New methods can take up to seven days to become effective.

Advice from a clinician is recommended when switching between contraceptive methods.

Stopping Contraception

With most methods of contraception, fertility returns immediately when the method is stopped. The exception is the progestogen-only injection (Depot-provera® or Sayana Press®). With both, it can take 6–12 months for fertility to return.

Women may want to stop contraception for various reasons, including times when they are not planning a pregnancy. Some women can be anxious about using hormones for any length of time or think it’s a good idea to take a break from hormones, or they may want to see what their natural cycle is like without contraception. However, resuming regular periods does not have any benefit, and the body does not need periods to be healthy. In fact, the absence of periods is beneficial to many women, reducing the risk of anaemia, for example. In addition, periods do not always indicate fertility, and women with irregular or no periods can still ovulate. Women who stop contraception to monitor their periods should be aware of the risk of pregnancy – unplanned pregnancies often occur at these times.

Women who are advised by a specialist to change their contraception should discuss this with the healthcare professional who they consult about contraception in order to avoid an unplanned pregnancy. For example, a surgeon may recommend stopping the pill before undergoing surgery, whereas changing to a non-estrogen method may be appropriate.

Frequent stopping and restarting combined hormonal contraception is not recommended as the risk of blood clots in the legs (deep-vein thrombosis) or lungs (pulmonary embolism) is increased slightly in the first few weeks of use.

Women who want to conceive can stop using contraception at any time and there is no need for periods to be re-established first. A woman may ovulate in her first contraception-free cycle, before her period. Women who need or want to optimise their health, weight or lifestyle before conceiving, or who need to modify medical treatments for established conditions, should continue to use contraception until they are ready to start trying to conceive.

Fact: It is true that fertility declines with age; however, it is still possible to get pregnant up until the age of 55. Unfortunately, many women believe that, as their periods become less regular, they are no longer fertile. However, they may still ovulate, which means they are at risk of pregnancy. Hormone-replacement therapy does not provide contraception. Fact: For young women who have a strong desire not to get pregnant, the patch (changed weekly), vaginal ring (changed every 3 weeks) or long-acting methods (the implant, injection, coil) provide more reliable contraception. Fact: Contraception does not affect fertility in the longer term. With the exception of the progestogen-only injection, fertility returns immediately after stopping contraception. Fact: Hormonal medications do not prevent ovulation, so trans and non-binary people who are having this type of treatment are at risk of pregnancy if they have heterosexual sex, even if they are not having periods. In fact, it is important to prevent pregnancy because medications can harm a developing baby. Myth 1: I’m too old to get pregnant

Myth 2: The pill is the best contraception for young women

Myth 3: I can just use emergency contraception

Myth 4: I need to stop contraception in plenty of time to allow fertility to return

Myth 5: Hormones used by trans and non-binary people prevent conception