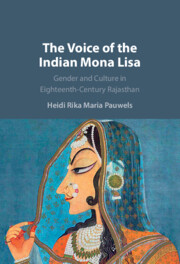

The cover of the November–December 2014 issue of the Indian Embassy in France’s journal Nouvelles de l’Inde featured an image of an “Indian Mona Lisa” (Figure 1.1). This 2006 oil on canvas was painted by Gopal Swami Khetanchi (b. 1968), who studied art at the University of Rajasthan in Jaipur and worked as an illustrator of magazines and as an assistant art director for Bollywood cinema before returning to Jaipur as a full-time artist (Bahl and Puri Reference Bahl and Puri2011: 12). His painting certainly was a good choice to grab the attention of a French audience, based as it was on the instantly recognizable image of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, indisputably the most popular attraction of the Paris Louvre Museum. The famous image has of course been the butt of many similar transfigurations (documented in Maell Reference Maell2015), most recently sporting masks in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, sparking “le plaisir du déjà-vu” (Saint-Martin Reference Saint-Martin2020). Khetanchi’s incarnation of “La Gioconda,” besides sporting an admirably slender waist, was dressed up richly in Indian style, with a diaphanous veil with golden pattern and border, red upper-garment (choli) with golden rim, several layers of pearl garlands interspersed with gold jewelry, and matching gold and pearl bracelet, earrings, arm, head, and nose ornaments. Clearly, she represented an Indianized version of Mona Lisa.

Figure 1.1 Bani Thani by Gopal Swami Khetanchi. 2006. Jaipur, India. Oil on canvas. 50.8 × 76.2 cm.

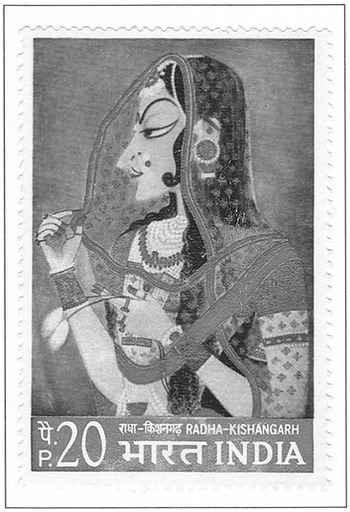

What might have escaped the non-Indian observer is the specific model for the Indian elements: These were not random but based on a mid-eighteenth-century painting of the Kishangarh school of Rajput painting. This “Lady with Veil” has been attributed to the master Nihālcand and is well-known in India as it was featured on a postage stamp issued in 1973 (Figure 1.2). Not only does the costume of Khetanchi’s Indian Mona Lisa match the lady’s, so does her delicate pose, with her hennaed right hand preciously pulling the veil, and the left one balancing two lotus stalks. While Khetanchi chose the three-quarter profile and frontal gaze of the famous portrait by the Italian master, he tilted the left eye somewhat upward to more closely approach the typical curve of the famed exaggerated Kishangarhi eye. Together with the nose ring, this created the effect of rendering Mona Lisa less melancholic as she meets the onlooker’s eyes slightly cynical, perhaps somewhat cheekily. This prompts the observer to wonder – the eternal Mona Lisa question – what lies behind this amused smile?

The magazine did not offer an explanation for the choice of this image for its cover. Its contents constituted a special issue on contemporary Indian literature, but the possible link with the lady was left up to the reader to ponder. Perhaps the connection of the location of Khetanchi’s studio in Jaipur, the locale of the eponymous Jaipur Festival of Literature featured in the issue, was assumed to be obvious. Yet the “Lady with Veil” alluded to by Khetanchi’s painting does have a deep literary connection, even if few realize it. The key lies in the official title of Khetanchi’s portrait: Bani Thani. This is the nickname of the purported real-life model, whose facial traits are believed to have inspired the eighteenth-century painting. Banī-ṭhanī was a concubine of prince Sāvant Singh of Kishangarh (1699–1764), the patron of the portrait. The prince is known to have commissioned many devotional paintings to match his own poetry in praise of Krishna and Rādhā (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015; Reference Pauwels2017). This particular painting is often understood to be a portrait of the Goddess Rādhā as he described her in his poetry, based on his concubine’s striking features.

“Banī-ṭhanī” or “Miss Decked Out” is famous for her looks and elegant sense of style, and widely regarded as the Indian equivalent of La Gioconda, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo who commissioned the Italian Mona Lisa painting. Like her famous Italian counterpart, Banī-ṭhanī is also shrouded in mystery, and it has been questioned whether she really was the model for the portrait. The most significant difference though is that Banī-ṭhanī was herself an artist, a performer as well as an author of devotional songs, which she composed under the pseudonym Rasikbihārī. It is entirely fitting that she would be featured on the cover of a magazine dedicated to Indian literature. So far though, hardly any of her poems have been translated, or even edited. This book allows us to hear her voice, featuring many of her poems translated and edited from a newly discovered manuscript. The main pursuit of this book is the connection of the portrait with literature: It is the search for the poetess behind “Lady with Veil,” Khetanchi’s work’s eighteenth-century model.

Before we meet Rasikbihārī the author afresh, we trace what we know of the “Indian Mona Lisa” and how we know it. This first chapter launches the book’s discovery project by first unpacking the implications of this trope, so compactly visually represented in Khetanchi’s painting. It seems to imply that the Indian master’s portrait is copycat work, but that is far from the truth. At first sight, this image may seem to partake in orientalism in its classical Saidian formulation: a projection of European fantasies onto the non-European “other,” rendering “the Orient” as a mirror image for the West (1978). The image can be interpreted as lacking realism in the stylization of the sitter’s individuality into a type, as reducing “the Orient” to the domain of luxury and wealth, symbolized in the lady’s rich adornments and of sensuality and eroticism, epitomized by the perceived model being a performer from the harem. Khetanchi’s Bani Thani seems to fit the prejudice to a T. But why would a contemporary twenty-first-century Indian artist employ an orientalist construct in his art?

This chapter investigates what is behind the trope and why it is so powerful. What does the comparison with Mona Lisa mean for a contemporary Indian audience against the background of an emerging market for Indian art among the rising middle classes? A sample of the reception of Khetanchi’s painting is the starting point for exploring current perceptions about the painting and the purported real-life model (Section 1.1). Where do these discourses come from? First, the “Lady with Veil” referenced in Khetanchi’s work is placed in her own art-historical context, within an eighteenth-century portrait gallery, to sort out whether the labels now current for the portrait would have fit contemporaneous notions when it was made (Section 1.2). Then, we trace the twentieth-century art-critical evaluation that produced the theory that Banī-ṭhanī was the model. Who were the agents, colonial (Section 1.3) and postcolonial (Section 1.4), that promoted and opposed the Mona Lisa trope? How did “Lady with Veil” become known as Portrait of Radha? Why did she go on to become a nationally recognizable image symbolized by the stamp issued in 1973 and end up as a cyber-orientalist tourist icon promoting her beauty and romance with the prince, while neglecting her authorship (Section 1.5)? This first chapter unravels the orientalist trope to prepare the way for an exploration of the artist behind the pretty cover of Nouvelles de l’Inde’s special issue on Indian literature. This act of “unveiling” sets us up for the quest to discover the woman author implied in the painting in the rest of the book

1.1 Returning the Gaze: The Orientalist “Indian Mona Lisa” Trope Subverted

The reception in India of Khetanchi’s canvas brings to the fore some important questions at the heart of Indian cultural appreciation today. A short BBC Hindi article from 2012 featuring the painting posed in its title the question that was posed to several respondents: “What if the Mona Lisa were Indian?” (Agar Monā Lisā bhāratīya hotī to?)Footnote 1 This counterfactual title implies Khetanchi’s painting throws a gauntlet, raises a challenge to the Western masterpiece in its reference to the eighteenth-century Indian one. All interviewees agreed that by fusing both, Khetanchi had forged the best of Western and Eastern beauty ideals. The move of dressing Mona Lisa up in Indian garb was read as challenging the notion that Western views of beauty are universal. Thus, the artist Ekeshvar Haṭvāl indicated that Khetanchi’s interpretation confers equal status to both Mona Lisas, and art critic Īshvar Māthur stressed that the Western and Indian beauty ideals each have their own place. This was confirmed by Khetanchi, the artist himself, who called his own work a samāgam or “confluence” of both types, contrasting Western voluptuousness (mā̃saktā) and intoxication (mādaktā) with Indian subtlety (nazākat) and refinement (nafāsat), the latter expressed by Persianate words, evoking sophisticated Mughal culture.

If the appeal of the image lies in the juxtaposition of competing perceptions of East and West, these are not just ideals of beauty, as in intoxicating flesh-and-blood physicality versus more refined subtlety, but of womanhood itself. The interviewees confidently confirm India’s competing not just on equal footing in the East–West beauty contest, but with a sense of superiority. Perhaps originally da Vinci intended to portray the demure and loyal wife of his patron, as exemplified by the clasped hands and slight smile conform etiquette manuals of the time,Footnote 2 yet to Khetanchi’s eye she becomes associated with voluptuousness and licentiousness. The lady in the Kishangarhi painting, on the other hand, is decorous and refined. La Gioconda has a delicate, hardly perceptible translucent head cover, but her gaze boldly looks back at the spectator, while her Indian counterpart coyly turns away, drawing the border of her veil presumably to cover her face. Khetanchi’s painting fuses this with a hint of cheekiness, which subtly undermines the stereotype of Indian women as demure. The sophisticated, yet decorous Indianized lady sports an ironic “last laugh.”

In his other artwork, Khetanchi has followed a similar pattern of reworking classical Western portraits of women, often nudes, transforming them into elegantly dressed Rajasthani beauties. Several of those canvases were on view in his 2008 London show “A Tribute to the Masters.”Footnote 3 Rather than dismissing this title as a form of flattery, a gimmick to break into an international art market, one could explore its appeal to middle-class NRI (Non Resident Indian) audiences. Similarly, the Indian interviewees for the BBC article praised Khetanchi’s Mona Lisa painting as an example of “fusion” art (using the English term in the Hindi), and saw it as astutely tapping into what is popular with a twenty-first century audience in India and beyond. The article signals an awareness of the rise of a new market for Indian art in an “India Shining” environment. University of Heidelberg popular culture professor Christiane Brosius characterizes this audience as engaged in a sustained effort to “Indianise modernity and cosmopolitanise Indianness” (2010: 328), which the painting illustrates perfectly. This is not unlike what has been observed for the popular culture of Bollywood cinema that constantly strives to outdo the West at its own game, but with a twist confirming in the end: phir bhī dil hai hindustānī “at heart I remain Indian.” At the same time that popular culture is preoccupied with the glamorous cosmopolitanism of the Indian abroad, it makes it a point to affirm its basically Indian emotional core (Kaur Reference Kaur, Kaur and Sinha2005: e.g., 310–11). This hybrid identity is characterized by an ambivalent relationship between the pull of the cosmopolitan and the call of the (lost) homeland. Yet, compared to the other paintings in the London show, there is more to the “Indian Mona Lisa” than market appeal.

How Bani Thani stands out amongst Khetanchi’s reworkings of Western “Masters’ classics” becomes clear in comparison with its twin, a slightly bigger canvas (61 × 91.4 cm) called Devashree, or Splendour of the Gods (Maell Reference Maell2015: 89). This painting represented simply a Mona Lisa in an Indian outfit, whereas Bani Thani referenced at the same time a well-known Indian master’s classic. The instant recognition of the Western work of art is repurposed to draw attention to the internationally lesser-known Indian one with which the Italian renaissance painting is fused. The kind of mimesis that this artwork performs then, is not simply that of a copycat or plaisir du déjà-vu. It does not take the form of straightforward imitation, or appropriation. It is closer to subversions of high-culture classics, to what inspired Marcel Duchamp’s irreverent 1919 L.H.O.O.Q readymade,Footnote 4 than to the self-advertising that treats her as a popular cultural icon, like Andy Warholl’s Thirty are Better than One (1963), or French street artist “Invader’s” Rubik Mona Lisa (Sassoon Reference Sassoon2001: 251–6).

The postcolonial context infuses Mona Lisa’s mimesis with an important dimension of contestation.Footnote 5 As is clear from the reception of Khetanchi’s painting, this form of mimicry includes a mockery that allows the artist not just to challenge but to upend Western concepts of art, beauty, and womanhood. In contrast to other Mona Lisas in ethnic dress, such as Alyssa’s in Tunisian costume of 1967 (Sassoon Reference Sassoon2001: 254), Khetanchi’s draws attention to an actual corresponding Indian masterpiece. In doing so, the Indian painter highlights the existence of a rich and in the West little-known art tradition that can rival the best of the Western canon itself. In the process, he shows up the smug obliviousness, the pretense of Western cosmopolitanism in the face of its own ignorance of global alternatives. Simply put, what appears to the undiscerning glance as mimicry, admiration, and imitation, has a deep bottom of critique and reverse mockery rooted in pride in its own heritage. The interviewees’ interpretations of Khetanchi’s work demonstrate how the perceived orientalist trope rather signifies the reverse: The Western imperialist gaze is cheekily returned.

There remains one more aspect of Khetanchi’s painting to unpack, again something less readable to the Western viewer, but brought out by the BBC article referenced here. Khetanchi gave his painting the title Bani Thani. Widely interpreted as the name of a real-life model, the woman whose features ended up defining the Kishangarhi type, this actually exposed Khetanchi to criticism. It was foremost in the mind of the writer and at least one of the interviewees of the BBC article. The Jaipur-based sculptor and Padmashrī award winner, Arjun Prajapati, critically suggested that Khetanchi would have done better to leave the famous Kishangarh portrait alone, as the original was the result of a unique collaboration between the artist and his patron, Prince Sāvant Singh of Kishangarh. Prajapati felt it was based on the prince’s loving descriptions of the features of his ladylove, which the painter then went on to capture on the canvas. Implying the lady in question was in purdah, he saw Khetanchi’s endeavor as disrespectful, and since the original depicted a Goddess, as an irreverent secularizing move.Footnote 6 The author of the BBC article chimed in, keeping the historical Banī-ṭhanī behind purdah by imagining her not as a flesh-and-blood woman, but as the heroine of Sāvant Singh’s dream that took form on canvas. Such discomfort with worldly women out of purdah spoke through Khetanchi’s own word choice, as his attribution of voluptuousness (mā̃saktā) to the Western Mona Lisa. An old orientalist discourse on art surfaces here, a colonial view that contrasts Western realism foregrounding materiality (read hedonism) with Eastern idealism stressing spirituality (restraint). Traditional Indian art is essentialized as symbolic and religious, without a direct link with observed reality (Guha-Thakurta Reference Guha-Thakurta2004). All this lays bare some discomfort with the term “Indian Mona Lisa,” which seems to be a contradiction in terms: a real-life naturalistic model for an Indian spiritual ideal type.

Whence came these persistent romantic mystifications? Why does the identification of Banī-ṭhanī as the Indian Mona Lisa seemingly compulsively return to the orientalist construct? Why do none of the commentators refer to her contributions to literature? There seems to be a strong discourse at work that keeps hijacking the conversation. Could this be because the portrait, and for that matter the Kishangarhi school of Rajput painting, was discovered by a British colonial agent who started writing about her in a certain vein? To grapple with those isssues, at this point let us telescope the Khetanchi image into its source of inspiration, the Kishangarh “Lady with Veil.” Before reconstructing the history of the art-historical perceptions that came to be projected onto it in twentieth-century discourse, let us first address its place in eighteenth-century portraiture.

1.2 “Lady with Veil” in the Portrait Gallery of Mughal and Rajput Women

What about the Indian Mona Lisa portrait, “Lady with Veil,” itself? The painting is not inscribed, so we do not actually know whether it was intended to portray the Goddess Rādhā, even less whether it has the features of the Kishangarhi concubine Banī-ṭhanī. Before tracing how it came to be associated with both these identifiers, situating the painting in its historical context helps determine whether either designation would have been likely at the time. We can build on the pioneering archival work of Dr. Faiyāz ‘Alī Khān of Kishangarh in the middle of the previous century and more recently on the art-historical work by Dr. Navina Haidar, Curator at the Metropolitan Museum and Oxford-trained specialist on Kishangarh art, who has written on this very portrait (Haidar Reference Haidar and Dehejia2004). At the outset, it is important to note that the Kishangarh school of painting from early in the eighteenth century developed in close exchange with the Mughal atelier, with artists trained in Delhi moving to the small Rajasthani principality (Haidar Reference Haidar and Dehejia2004; Reference Haidar, Beach, Fischer and Goswamy2011a; Reference Haidar, Beach, Fischer and Goswamy2011b).

“Lady with Veil” itself has mimetic elements of Mughal and European portraits, though no direct connection with the Italian Mona Lisa has been made.Footnote 7 It definitely is not a copycat work, but in many ways, it conforms to the type of the single, nonnarrative bust portrayals of idealized beauties designed to be admired in albums that were popular by the eighteenth century both in Mughal and Rajput painting. While actual inscribed portraits of palace women were rare, bust portraits of this type were relatively common.

In Mughal art, the seventeenth century had seen a marked increase in portraiture of women,Footnote 8 Abu’l Hasan’s full-length portrait of Nūr Jahān in male outfit with a gun being perhaps the most remarkable. Attributed to the same painter was a bust portrait of a Mughal lady, meant to be worn as a jewel, possibly also Nūr Jahān’s.Footnote 9 The first dated (1628) oval bust portrait of an imperial lady was actually the empress’ niece, Mumtāz Mahal. Painted on a mirror case by the Mughal atelier’s master painter ‘Abīd, it was likely inspired by a European allegorical model (Seyller Reference Seyller2010b: 145–53).Footnote 10 This portrait was intended for her husband Shāh Jahān, for private hands only, as was the 1630–3 album that Dara Shikoh gifted to his wife Nadira Banu Begum with its full-length portrayals of women from the imperial zanānā. This proved trend-setting and an explosion of portraits of ladies occurred in its wake.Footnote 11Window or jharokhā-style profile portraits of palace ladies became popular after 1668, when Aurangzeb abandoned the practice of imperial appearance to his subjects at the palace window (jharokhā), thereby renouncing the previous reservation that only the emperor could be thus portrayed (Losty and Roy Reference Losty and Roy2012: 141–3). A few such bust portraits have been demonstrably modeled after European originals.Footnote 12 The vogue of unidentified women’s bust portraits (often with revealed breast) spread to the provinces and became particularly popular in the eighteenth century.

The features of the women in these Mughal portraits often strike viewers as generic and stylized, so it has been suggested that these eighteenth-century paintings were essentially ornamental and not intended as portraits at all.Footnote 13 The idealizing nature of the portraits is often explained by the painters’ lack of access to ladies in purdah, though it has been established that women painters were active in zanānās.Footnote 14 Still, art historians often designate the more life-like looking depictions as portraits of more accessible “courtesans” or “harem attendants,” especially when holding a wine cup with hennaed hands.Footnote 15 Less ambiguously, other portraits depict musicians with their instruments, or clapping their hands, making clear their status as performers.Footnote 16 A few such paintings are inscribed, sometimes identifying the lady by ethnicity, such as Muhammad Afzal’s circa 1740 Gujarātī Woman (chahrā-e Gujarātin; Losty and Roy Reference Losty and Roy2012: 183, fig. 124). It has been suggested that in the case of palace women behind purdah, the real identity of the ladies was purposely hidden under generic ascriptions to powerful queens who did appear in public, such as Sultānā Chand Bībī, Bijapur regent for her minor son and enemy of Akbar, and most famously Nūr Jahān, Jahāngīr’s consort.Footnote 17 Notwithstanding the above-mentioned contemporaneous portraits of the powerful empress, it is the posthumous idealized depictions from the eighteenth century that became popular.Footnote 18 Both courtesan and queen are combined in the case of Lālkuṃvar, the performer-turned-empress married to the emperor Jahandar Shāh who was deposed in 1713 (Figure 1.3). For many portraits, whether idealized or real-life, a common characteristic is that the ladies are depicted with one hand delicately raised towards the face, often holding a flower or a cup. Our “Lady with Veil,” with her hand raised toward the face, preciously holding her veil, certainly does not look out of place in the gallery of such Mughal lady portraits.

Figure 1.3 Portrait of Lal Kunwar. Eighteenth century. Mughal, India. Color-wash drawing. 32.6 × 21.5 cm.

Since Rajput portraiture generally developed in close interaction with its Mughal counterpart (Desai Reference Desai, Schomer, Erdman, Lodrick and Rudolph1994: 313), it is to be expected that depictions of Rajput ladies partake in the same characteristics. Some Rajput jharokhā-style lady portraits are clearly copies of Mughal examples, such as a Kishangarhi mid-eighteenth-century idealized copy of the famous Nūr Jahān portrait, which seems a likely candidate of being intermediary towards “Lady with Veil” (Figure 1.4).Footnote 19

Figure 1.4 Idealized Portrait of the Mughal Empress Nur Jahan (1577–1645). Ca. 1725–50. Kishangarh, Rajasthan. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. 29.52 × 21.59 cm.

Like their Mughal counterparts, Rajput portraits of women also rarely identify the model (Aitken Reference Aitken2002: 449–50).Footnote 20 A few portraits were inscribed with a generic noble woman’s name, for instance “Jodhabāī.”Footnote 21 The absence of identifications of the sitter can be understood with reference to the male-exclusive spheres of power within which portraits circulated, namely the genealogical record and gift-giving to ensure allegiance (Aitken Reference Aitken2002: 254–6).Footnote 22 Here, the question whether painters had access to palace women to sketch a portrait based on observation looms large. It seems self-evident that women in the Rajput zanānā could not be observed, so it is not surprising that popular press articles on Banī-ṭhanī, like the BBC piece quoted above (Agar Mona Lisa Bhāratiya hoti to?) take for granted the impossibility of direct observation for the Rajput harem portraits. One respondent assumed that Sāvant Singh himself either described in words or actually sketched a portrait of his mistress for his favorite painter Nihālcand to work with. Possibly, he had in mind an existing sketch “portrait of a yogini” that was drawn by the crown prince himself (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015: 201–3). However, that drawing was not inscribed with reference to Banī-ṭhanī, nor actually do the features of this “yogini” show the extraordinary profile the singer is famous for. The point is rather that there may actually not have been any need for such intermediation by the prince. As a court singer, Banī-ṭhanī was not behind strict purdah.

As in the Mughal case, Rajput portraits of musicians are plentiful.Footnote 23 A few such Rajput portraits of performers carry identifications, often with the epithet of bhagtan or “courtesan,” which confirms that they were sometimes based on living models.Footnote 24 All this indicates that the assumption that individual women were not depicted needs to be nuanced. Rather, as Aitken perceptively suggests, portraits existed but were often not inscribed with the women’s names and thus the contextual information of who was the model was lost over time (Aitken Reference Aitken2002: 256, 273–4).Footnote 25 In the case of Kishangarh, there are examples both in full and three-quarter profile (see Figures 1.5 and 2.2 in this book). While not inscribed, one of them certainly shows the characteristics associated with Banī-ṭhanī, in particular the elongated eye and brow, and the prominent nose (Figure 1.5). However, does that make the image a portrait of Banī-ṭhanī? It does not take much to see it as a forerunner of the more stylized and exaggerated features of “Lady with Veil,” where she holds a lotus instead of a musical instrument. However, the conundrum is whether Banī-ṭhanī was the model for or modeled after the distinctive Kishangarh style, an issue to which we will return (Section 3.1).

Figure 1.5 A Lady Singing. Ca. 1740–5. Kishangarh, Rajasthan. Painting on paper. 48.2 × 35.2 cm.

Scholars have posited that “most depictions of women of the Rajput courts were generic and not portraits of actual people. In place of specific character traits, artists highlighted the feminine sophistication, beauty and mesmeric behavior of the women” (Mishra Reference Mishra2018: 137).Footnote 26 Molly Aitken has sought to nuance this common assumption, citing examples that show it was at least not inconceivable painters had access to palace women (2002: 149–51), though she hastens to specify that the women were portrayed not individually but conventionally, with the stylistic face of the local school of painting (272–5).Footnote 27 Columbia University art historian Vidya Dehejia has plausibly suggested that this development of formulaic portrayal was used “in a manner akin to the use of a flag or insignia, as a feature that individualized and distinguished them from adjoining princely courts… most prominently the female form became the hallmark of a state” (1997a: 362). This applies well to Kishangarh, which is the example Dehejia cites. In that light, the Kishangarh court’s insistence that “Lady with Veil” is not a portrait after a real-life woman is well-justified.

Ignoring the model’s actual physiognomy is all the more pertinent for women portrayed within more elaborate court or harem scenes where their husbands or patrons are central. The aesthetic preference for uniformity and generically stylized features for everyone but the king sidelines specifics of individual appearance, not just for the ladies, but for courtiers and attendants in general. However, within strongly hierarchical Rajput society, one suspects that the participants in the activities portrayed would have been very sensitive to who was represented where in the hierarchy, and which ladies were singled out for attention, even if the names were not recorded. This would seem obvious in particular for hunting scenes that depict ladies’ shooting exploits. (For an example from Bundi ca. 1760, see Bautze and Angelroth Reference Bautze and Angelroth2013: 116–7.) In the Kishangarhi context, there are several portraits that inscribe courtiers by name just above their depiction or have keys on the back (examples in Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015: 70–71, plates 2 and 3). Awareness of the identity of the portrayed then seems to have been keen, even when the portrayal was not individualized.

The conundrum of verisimilitude is tied up with the determination of intention, that is, whether specific individuals are intended to be portrayed in a historical location, or conventional scenes with generic characters. In the case of both Mughal and Rajput painting, some “portraits” actually depict ideal-type heroines, rāgamāla series, scenes from Krishna’s life, or generic conventional harem scenes, like ladies bathing, holding birds, making music, or carrying water pots (panihārin). A Kishangarhi example is a well-executed full-length portrait of a charming water carrier by the lake with her pot put down, waiting for her beloved, presumably the horseman in the background. This has been attributed to Bhavānīdās, the painter who moved to Kishangarh from the Mughal atelier.Footnote 28 Strikingly, like the Mughal jharokhā portraits, she too has one hand raised delicately to the height of her face. This portrait, dated around 1725, can be related to a similar image that is attributed to Bhavānīdās’ son Dalcand and slightly later, ascribed to his maturity phase, 1730–40 by McInerney (Reference McInerney, Beach, Fischer and Goswamy2011: 574–7, fig. 13). In this case the lady is holding a flower in her hand raised to shoulder height, like the portrait of Lālkuṃvar (Figure 1.3). Perhaps the garland that the lady is holding in her other hand hints at her intent to garland her “groom” upon arrival. Here, too, there is a horseman in the background; clearly it is intended to echo the father’s painting. One suspects there is more going on here than generic depictions of ideal types, but the meaning behind that is now obscure. Both full-length portraits may well be taken to foreshadow the more stylized later bust portrait “Lady with Veil.”

Set portrayals sometimes illustrate so-called Rīti or mannerist poetry, which features a catalogue of hero (nāyaka) and heroine (nāyikā) types. This genre is found in classical Hindi literature; most famous perhaps are Keśavdās’ Rasik-priyā (The Connoisseur’s Darling) and Bihārī’s Satsaī (Seven-Hundred Poems), two of the most-illustrated classics of Hindi literature. The nāyaka-nāyikā genre has long antecedents in Sanskrit literary categorizations but is also discussed in Persianate-inspired Hindavi literature, following the exposé by Abū’l Fazl in ‘Ain-i Akbari.Footnote 29 Thus, what looks like a portrait may be an illustration of a nāyikā subtype, for instance, of the virahinī, the lady pining in the absence of the lover.

“Lady with Veil” has been identified by some as an example of a nāyikā of the type vāsaka-sajjā, “All dressed up (sajjā), awaiting her lover in her room (vāsaka)” (Dickinson Reference Dhavan and Pauwels1950: 35). This category of heroine is typically portrayed in painting as eagerly awaiting her lover with the decorated but empty bed ready nearby (vāsaka-śayyā; Coomaraswamy Reference Coomaraswamy1916: 51–2). The heroine depicted in the “Lady with Veil” painting certainly is beautifully dressed up, but there is no hint of the waiting bed that is the usual giveaway in pictures of this type of heroine. Neither is her demeanor expressive of the mood of anxious anticipation due to the lover’s delayed arrival. The coquettish smile and flirtatious gesture of adjusting her veil to reveal her beauty rather suggest that the lover has arrived, and we witness the play of seduction. So perhaps she does not fully conform to the traditional trope, but there may be another classical Hindi poem underlying the illustration. More on this will follow, as we discuss the art-historical journey of the portrait (Section 1.4).

To complicate matters, there is evidence that some of the seemingly abstract and conventional Rīti literature itself was in fact more or less obliquely directed to specific “courtesans” or palace ladies. One famous example from the late-sixteenth, early-seventeenth century is the aforementioned poet Keśavdās, who in his Kavi-priyā’s The Poet’s Darling frequently references his “disciple,” Pravīnrāy, the courtesan (pātur) at the Orchha court (Dehejia Reference Dehejia2013: 10–11). Distinctions between depictions of ideal-type and of real-life woman could become blurred, as when generic harem scenes are inscribed with the names of pāsbān or dancers from Mewar and Marwar, and when a Rāginī personified is identified on the painting as a Jaisalmer princess (Aitken Reference Aitken2002: 272–3).Footnote 30 Such would have enhanced the piquancy of the poems and paintings for the insiders, while remaining largely unrevealed to outsiders. This is not limited to the ladies. Court panegyrics, composed for specific rulers, depicted them, too, as ideal “heroes” or nāyakas.Footnote 31

This ambiguity and conflation is further deepened, as standardized depictions in apparent Rīti style are often identified as the Goddess Rādhā, thus imbuing the poetry with a devotional (bhakti) aspect.Footnote 32 That explains why “Lady with Veil” is deemed not just an ordinary portrait but reckoned to fall in the category of the idealized portrait of a deity, Portrait of Radha. Parallel depictions of Krishna with the features of rulers are well documented. Vidya Dehejia sees such conflation of God and “hero” or nāyaka (2009: 159–99) as a logical outcome in a cultural universe that has “routinely blurred the boundaries between sacred and profane,” and that sees gods as “the prototype for all human lovers” (161). Yet she also notices how the portrayal of women as “heroines” or nāyikā (and as consorts of the divine) is different from that of the rulers. The features of the heroines tend not to be differentiated from those of other women members of the court but identified only by contextual placements with their divinized partners. The “Lady with Veil” case is exceptional as, at least here, the nāyikā stands on her own.

How likely is it that an artist would depict the Goddess based on an individual woman’s features? There is evidence of portraits of historical royal women idealized as deities in Indian art. In sculpture, most famous is the example of the tenth-century Chola Queen Sembiyan Mahādevī portrayed as Pārvatī (Dehejia Reference Dehejia1998; bronze in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution). Dehejia provides the ritual context when the image was carried in procession on the occasion of festival celebrations. She perceptively connects this with images of Tamil saints-devotees, who are carried in processions that elicit narratives about their devotion (1998: 43–5). Similarly, the case of Sāvant Singh and Banī-ṭhanī is seen “to allude to their alleged special relationship” with Rādhā and Krishna (Crill Reference Crill, Crill and Jariwala2010: 37–8). In other words, the god-portrait might be intended to highlight the sitter’s devotion.

This can also be understood as an extension of portrayals of rulers partaking in the realm of the divine, as was popular at the time in the small principalities of Bundi and Kota. Possibly there is a link with the Vallabhan school of nearby Nathdwara that came into its own with depictions of the deity of Śrī Nātha Jī worshiped by his priests and visiting royalty. Those were called manoratha or “vow” as they commemorated the pilgrim’s visit often undertaken in the context of a special vow.Footnote 33 Next to the patron might be portrayed his family, including the ladies (Ambalal Reference Ambalal1987: 80). This is not limited to the Vallabhan sectarian milieus; kings are often shown with their own favorite or state deities, who are sometimes pictured in an anthropomorphic way, making it hard to distinguish between them and human personalities, conflating king and God.Footnote 34 Not much work has been done on non Vallabhan traditions as of yet, but notable is a drawing of Savāī Jai Singh II and the Caitanya Sampradāya image of Govindadeva Jī that he installed in his new capital Jaipur (Tillotson and Venkateswaran Reference Tillotson and Venkateswaran2016: 68). This image also features a woman fanning the deity, perhaps intended to represent a palace lady. However, it might be just as well a mythological figure, as she resembles the Goddess Rādhā and sakhī Lalitā in the painting next to the deity itself. On the basis of this confusing evidence, at least it is fair to say that Rajput paintings routinely show several levels of conflation of divine and royal realms.

Rulers often project themselves into the divine world, conforming to the common devotional technique of participation in dramatized performances of the deities’ lives. Mewar ruler Jagat Singh II (r. 1734–51) famously had himself portrayed assisting in such musical plays (e.g., Tillotson Reference Tillotson1987: 6–7, fig. 4; Khera Reference Khera2020: 90, fig. 3.1). We know that Sāvant Singh took part in Rās-līlās, or Krishna devotional plays (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2017: 91–105). There is evidence from Kishangarh paintings from the time of Sāvant Singh’s father, Rāj Singh, where the royal family is portrayed as attendants participating in celebrating Krishna’s marriage ceremonies (Haidar Reference Haidar, Beach, Fischer and Goswamy2011a: 543–4; Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015: 152–6). Nihālcand goes a significant step further in the identification of the devotee-prince with Krishna himself but it is not unparalleled; other kings also had themselves pictured as God incarnate.Footnote 35 In the case of Sāvant Singh, perhaps the male devotee’s promotion can be understood in the light of his devotional name “Nāgarīdās,” or “Servant of Rādhā.” Isn’t Krishna himself Rādhā’s greatest servant? Still, portraying a concubine as Rādhā? We should be careful not to introduce unwarranted Western art-historical tropes of Madonnas modeled after real women, including mistresses of painters and their patrons.Footnote 36

To sum up, after weighing all the pros and cons, our conclusion has to be nuanced. According to contemporaneous practice, we can reasonably assume that “Lady with Veil” illustrates a description of a heroine according to classical poetic conventions, and such nāyikās would frequently be identified as Rādhā. The interpretation of “Lady with Veil” as Portrait of Radha then seems quite apt. The unofficial title “Banī-ṭhanī” though is more dubitable, and whether the portrait was actually inspired by the beautiful concubine’s features remains up in the air. The identification is not impossible: There are examples of Rajput portraits of performers at court and stylized images may be intended to portray actual court ladies. At the same time, this case is not established as fact, as is sometimes assumed. What we can say with confidence is that the portrait was conceived within a realm of beauty ideals, imagery, and poetics that set Mughal and Rajput, classical Hindavi and Hindi literature into rich dialogue. In literature, as in painting, there is a generic conflation between portrait, depiction of the ideal, and of the divine.

1.3 Colonial Construct? An Aesthete’s Discovery of Portrait of Radha

How has “Lady with Veil” been interpreted subsequently over time? Khetanchi’s “Indian Mona Lisa” painting accomplishes visually the identification of Banī-ṭhanī as Rādhā with that of La Gioconda as Mona Lisa. This is the apotheosis of a development that has been in the making for about eight decades, forged in the crucible of colonial and nationalist discourses since the “discovery” of Kishangarhi art by the international art world. The Kishangarh school of painting was brought to the attention of the Western and Indian art connnoisseurs by Eric Charles Dickinson (1893–1951), a poet and short story writer who had been professor of English at Government College in Lahore since 1928 (Singh Reference Singh1952). In 1943, on an educational delegation to Mayo College in Ajmer, Dickinson’s party made a side trip to Kishangarh, where the young Rājā Sumer Singh (r. 1939–71), himself a student at the college, still reigned under a Council of Regency. Seven years later, Dickinson himself described the incident with dramatical flair in an article published in the prestigious Indian art Journal Mārg:

When on a September afternoon of 1943, a party of visitors entered through the high arched gateway leading into the ancient fort and palace of the Rathor chieftains of Kishangarh towering high above the lake of Gandaloo [sic] and took the salute of the sentry, not one of us had the least premonition that we were on the eve of a remarkable discovery…. The extraordinary… suddenly obtruded when the present writer grown a trifle weary of an over surfeit of wazirs, omrahs, princes, and badshahs inquired if any paintings existed dealing with a Krishnaite theme …. A peon … returned shortly carrying a portfolio which opened to disclose paintings of an unusual magnitude each contained in a tracing linen envelope. The first glimpse was sufficient to assure us that there was something quite unusual if not unique.

The orientalist trope of the thrill of discovery has been a mainstay in popularizing Kishangarhi painting ever since. In his insistence on seeing the Rajput artworks, which he preferred above the “tedious” Mughal ones, Dickinson undoubtedly was inspired by the influential art historian Anand Kent Coomaraswamy (1877–1947), who in his path-breaking book Rajput Painting published in 1916, had raved about the Rajput paintings’ exceptional emotional depth in comparison to Mughal ones:

If Rajput art at first sight appears to lack the material charm of Persian pastorals, or the historic significance of Mughal portraiture, it more than compensates in tenderness and depth of feeling, in gravity and reverence. Rajput art creates a magic world where all men are heroic, all women are beautiful, passionate and shy, beasts both wild and tame are the friends of man, and trees and flowers are conscious of the footsteps of the Bridegroom as he passes by. This magic world is not unreal or fanciful, but a world of imagination and eternity, visible to all who do not refuse to see with the transfiguring eyes of love.

Dickinson felt the discovery of his own “magic world” was cemented through establishing a connection between the images and the texts that were written on the reverse:

It was not long before I was convinced that so lyrical a content, as our paintings revealed, could be justified by only one factor: a text. Once this was determined upon, the implementation of discovery became long and arduous. One clue and only one was concrete. Upon the reverse of one of the miniatures it was noticed were several lines of writing in Hindi script.

He returned to Kishangarh with the express purpose to explore further the link of the paintings with texts, and found out about the collaboration of Sāvant Singh, alias Nāgarīdās, the poet-patron, and the painter Nihālcand.Footnote 37 He describes his reaction in rhapsodic terms:

And then suddenly on to the enchanted air down the forest aisles is wafted fragments of whispered colloquies of love, the words ever seeming to evade the strained ear of the devotee, since if he won the secret he would go mad with joy.

In stressing the interface between paintings and vernacular literature, Dickinson again took his cue from Coomaraswamy. As Keeper of Indian Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the latter would frequently assess newly acquired Rajput paintings:

This is anything but a primitive art: it is an art of saturated experience, and its simplicity is only apparent. In these respects it closely parallels the language of the contemporary vernaculars, such as the Hindi of the text, where by loss of the inflections characteristic of the older Prakrits, words have been reduced to their bare roots, and the meaning of a sentence must be grasped intuitively more than by logical analysis. The longer one studies this literature and painting, the deeper and fuller one finds its content.

For Coomaraswamy, the link between painting and literature was directly related to the idealism and spirituality of Indian art.Footnote 38 Similarly, Dickinson was prone to see Rajput art at its finest as religiously inspired “Hindu art.” Granting that the paintings were stylistically aware “of Moghul technical innovation and linear purity they yet, in inspiration, remain faithful to the Rajput ethos.” He even spoke of a “Hindu art renaissance flourishing … following the decline of the Moghul pre-eminence” (1950: 37). Coomaraswamy had devoted a full chapter of his landmark study, Rājput Painting, to Krishna Līlā, with a special appendix on the cult of Śrī Nātha Jī (1916: 2:26–41). Dickinson learned about the Kishangarh court’s view that the religious significance of Nāgarīdās’ poetry was connected with this same influential Krishna devotional movement, whose main temple was that of Śrī Nātha Jī. The Vallabha Sampradāya, named after the sixteenth-century philosopher Vallabhācārya, had a non-ascetic approach to the divine that made it attractive for wealthy householders, including rich Gujarati merchants as well as Rajput rulers. This system became known as Puṣṭi-mārga or “The Path of (God’s) Sustaining Grace,” which Dickinson seems to have understood as “The Way of Pleasure,” the title he gave to his 1950 article. Hence, he felt there was a religious justification behind the “frankly hedonistic appeal of the paintings” (1950: 34).

Dickinson provided the caption Portrait of Radha for the painting that later would become the basis for the Radha–Kishangarh stamp, and eventually Khetanchi’s fusion canvas (1950: 35). He was the first to cast it as the archetype for the Kishangarhi facial traits and attribute it to Nihālcand. He reckoned it was:

the assured masterpiece of his inventive formula for the lady with the tilted eye. In this eye and eyebrow sharply thrusting upwards Nihal Chand in one clear moment of divination has achieved a stylistic distinction for the Kishangarh ateliers over the rival school of Jaipur. An enigmatic quality is imparted to that splendid gash of the half closed eye sweep conveying the maximum of eroticism to the emotional moment of the time when Radha is at last confronted by the Divine Bridegroom.

To support his point, he cited a lush poem in English, presumably a translation of a Hindi work by Nāgarīdās, but he did not indicate the original source.Footnote 39

Dickinson’s was an aesthete’s perspective,Footnote 40 and he classified the image according to Indian aesthetics:

What an astonishing feast is here before us in this seductive study of a Rajput maiden …. Those well versed in the sringa rasa [sic] will have no hesitation in judging the rasa of the painting to be that of the vasakasaya nayika, or the tender maiden who has made ready for the long awaited arrival of the beloved.

This analysis employed the terminology of Indian aesthetics. Again following Coomaraswamy (Reference Coomaraswamy1916: 2:42–54), he classified according to theories of Śr̥ṅgāra rasa or the “erotic sentiment” and the typology of heroines (nāyikā). This is sophisticated, even if one might quibble with his choice of the particular type of the vāsaka-sajjā “all dressed up and awaiting her lover on the bed” (as discussed in Section 1.2).

Dickinson spoke of the Rādhā in the portrait as a “tender maiden,” a coy virgin on her wedding night.Footnote 41 These musings evoke bridal mysticism, which made sense in the context of the preoccupations in contemporaneous art-historical writing about India. Again one can compare with Coomaraswamy’s views that glorified the purity of the Indian bride in “rhetorical pamphlets on The Oriental View of Woman (1910) and Sati: A Vindication of the Hindu Woman (1913), where the act of Sati (also spelled suttee) was glorified as ‘Eternal Love,’ representing the most sacrosanct image of Indian womanhood” (Chattopadhyay and Thakurta Reference Chattopadhyay, Thakurta and Bagchi1995: 164). The famous art historians, Mohinder Singh and Doris Schreier Randhawa, writing in 1980, deemed Dickinson’s evaluation of Kishangarhi art as subscribing to “the romantic cult of innocent womanhood” (1980: ix). There was a palpable tension in his attempt at framing the image within Indian aesthetic categories that presumed a sexually experienced heroine, and at the same time the urge to represent the essence of Rajput art as pure spiritual love, foregrounding an innocent one.

Was Dickinson the one who came up with the Mona Lisa trope? Certainly, comparison with European art was typical for the art-historical discourse of the time. It made sense in a context where scholars of non-Western art felt the need to advocate for their subject in terms familiar and appealing to a largely Western audience. This had become even more pertinent against the background of political assertion of the struggle for independence, when the need arose of “acknowledging South Asia’s arts as fine arts, worthy to rival the European canon” (Aitken Reference Aitken2016: 10). Dickinson, too, invoked Western parallels in his writings. He did not mention da Vinci, though he compared “Lady with Veil” with the celebrated profile portraits by fifteenth-century Italian masters (1950: 35).Footnote 42 He also brought up other profile-oriented painting styles, such as the Minoan cupbearers of Knossos and the art revolution under the 14th-century BCE Egyptian pharaoh, Akhetaton. Perhaps the latter betrays that Dickinson saw himself as tracing the footsteps of Egyptian archeologists, such as the German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt, who in 1912 discovered in Amarna the bust of Akhetaton’s Queen Nefertiti. Akhetaton’s love for art, the “realism” of the bust modeled after the queen’s features, and the pair’s shared religious inspiration would parallel the Kishangarhi case. It must be said though that Dickinson did not mention Nefertiti at all in his published writings on Rādhā’s Kishangarhi portrait.

In his efforts to promote Kishangarh to the top of world art, Dickinson kept racking his brain for Western parallels. Here he parted company with Coomaraswamy who, in his enthusiasm for the religious aspect of Rajput painting drew mainly parallels with medieval European art (Mitter Reference Mitter1977: 279). Instead, Dickinson eventually settled on Jean-Antoine Watteau’s roughly contemporaneous (1717) Embarkation for Cythera (the island where Venus was born) (L’Embarquement pour Cythère) (Dickinson Reference Dhavan and Pauwels1950: 33).Footnote 43 This painting, submitted to the Académie Royale in Painting and Sculpture had inaugurated a new genre, that of the Fête galante or “arcadic revelry.” While he did not elaborate, Dickinson here brought up an interesting comparison. The nostalgia for the pastoral innocence of mythic Arcadia during this post-Louis XIV Régence period of decadence had a lot in common with that for the Krishnaite pastoral of Sāvant Singh’s time. The late Indologist Alan Entwistle identified several parallels between French arcadian and Kishangarh’s Vaishnava paintings, at the heart of which was the celebration of unencumbered love in bucolic scenes through dramatic staging. Addressing interpretations of such fantasies as escapism, Entwistle perceptively pointed out the tensions at work when sophisticated courtiers fetishize the countryside’s charms, sometimes as idealized childhood experiences (1991). While Dickinson did not spell it out as elaborately, he too was on to something more profound than the shared theme of savvy courtiers frolicking in the countryside.

In sum, the British teacher at Lahore college, Eric Dickinson, was instrumental in bringing Kishangarh paintings to the attention of the Western (and Indian) art world. He enthusiastically described them in the style of contemporaneous art-historical treatment of Indian art, for which Coomaraswamy had set the tone.Footnote 44 This discourse partook in colonial practices of comparisons with European art and orientalist tropes, including fascination with the timeless spirituality of the Orient. Following Coomaraswamy’s spiritualization of the feminine in Rajput paintings, Dickinson characterized “Lady with Veil” as Portrait of Radha, and attributed the Kishangarhi “Hindu renaissance” to sectarian religious inspiration. In relating Kishangarh’s art to the best of the West, Dickinson went beyond Coomaraswamy’s parallels with classical or medieval art, comparing with the “arcadic revelry” paintings of Watteau for the Versailles nobility. Departing from “Coomaraswamian anonymity” (Ehnbohm Reference Ehnbohm and Barnett2002: 181), Dickinson attributed the prototype of the Kishangarhi facial type to the master painter Nihālcand who worked with the patron-poet Nāgarīdās. Introducing historical concerns, he ascribed the development of this distinctive style to rivalry with nearby ateliers of Jaipur and Jodhpur.Footnote 45 This concern with historicity too differed from Coomaraswamy’s orientalist notions that tended to be essentialist and idealist (as evaluated by Mitter Reference Mitter1977: 279–86; see also Singh Reference Singh2013: 257–60). If Dickinson’s surmise is right, it is ironic that what started as a symbol of regional pride of Kishangarh over Jaipur, became in the twenty-first century a symbol of national Indian pride asserting superiority over Western ideals of beauty, art, and womanhood in the hands of the Jaipur painter Khetanchi. Nowhere in his single-authored articles though, does Dickinson make explicitly a parallel with the Mona Lisa, thus he was not the originator of that “colonial construct.”

1.4 The Search for the Model behind “Lady with Veil”

If the “Indian Mona Lisa” trope did not strictly speaking come from the pen of the colonial discoverer of the art, whence came the now common association apotheosized in Khetanchi’s contemporary double-portrait? Two further steps were taken: first, the identification of Banī-ṭhanī’s features as the basis for the Kishangarh type, and second, the comparison of this Kishangarhi model, concubine of Sāvant Singh who was the patron of the painting, with La Gioconda, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo who commisssioned da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Dickinson’s probing questions about the possibility of a real-life model for the striking features of the Kishangarhi face functioned as a catalyst for the crystallization of the identification, but there were other agents who played a definitive role in creating the myth. First comes to mind the man who saw Dickinson’s work posthumously through to publication and added his own insights, the lawyer and art connoisseur, Karl Jamshed Khandalavala, about whom more below. But there were other important players who paved the way. Several early Indian contributors to the construction of this trope have been neglected while attention was focused on Dickinson’s discovery.

Dickinson himself ignored an article on Nāgarīdās that was published as early as 1897 in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.Footnote 46 The author was Pandit Mohanlāl Vishnulāl Pandia, formerly the minister of the state of Pratapgarh in Rajasthan. He had already mentioned Banī-ṭhanī in connection with Nāgarīdās (1897: 66–7). He even provided a sample of her poetry under the pen name Rasikbihārī, correcting the common perception at that time that the poet by that name was a man. Few commentators mention this article, even though it appeared in English in a prestigious journal. Even fewer mention Pandia’s acknowledged source: the Hindi work of Bābū Rādhākrishnadās, the first director of the organization for the promotion of the Devanāgarī script or Nāgarī Pracāriṇī Sabhā of Varanasi (NPS, established in 1893).Footnote 47 He had given a presentation on Nāgarīdās in 1894, which was published by the Khaḍag Vilās Press, but subsequently rewritten with input of the Kishangarh court’s chronicler Kavi Jaylāl for the foreword of the first lithograph edition of Nāgarīdās’s works published in 1898 (Gauḍ Reference Gauḍ1898: 1–30; see Section 5.4). These publications focused on Kishangarhi literature and perhaps that is the reason they did not make it onto the art historians’ radar. While the focus here is on the paintings, we will have occasion to return to the work of the Hindi scholars (especially in Chapter 5).

The giant on whose shoulders Dickinson was standing (and all of us writing on Kishangarh are indebted to), was another savant-courtier, this one at Kishangarh itself, by the name of Faiyāz ‘Alī Khān (1911–2001). By virtue of his position at court, Khān had been studying its archives and collecting materials on the topic of Kishangarhi paintings and the patron Sāvant Singh. When Dickinson visited, he was in the process of writing a dissertation in Hindi on Nāgarīdās at the University of Rajasthan, Jaipur.Footnote 48 Later he penned another dissertation at the same University, but this time for the English Department, on “The Kishangarh School of Painting” (1986).Footnote 49 The unassuming yet erudite Khān was close to the Kishangarh ruler Sumer Singh and, while a Muslim, served in many ways as the court’s spokesperson for its Vallabhan sectarian interpretation.

Dr. Faiyāz ‘Alī Khān also advised the scholar Kiśorīlāl Gupta, who edited the works of Nāgarīdās for the prestigious Nāgarī Pracāriṇī Sabhā of Varanasi, which came out in two volumes in 1965. Gupta reports he had been working on Nāgarīdās for over a decade, mainly based on the 1898 lithograph published by the Kishangarh court.Footnote 50 He had remained unaware that its Vallabhan discourse had been challenged by a rival Nimbārkan claim on Nāgarīdās till his book was already in press; still he made a hurried trip to Kishangarh to seek clarity about Nāgarīdās’ sectarian allegiance. Unable to make it to the Nimbārkan monastery in nearby Salemabad, he visited the temple in the Kishangarh fort and met briefly with Dr. Khān, who confirmed the Vallabhan claim. Khān himself had already finished the manuscript of his own edition, but it was not yet typed up (Gupta Reference Gupta1965: 1.1–4). Consequently, Gupta did not modify the Vallabhan interpretation of his own edition, which was immediately challenged by the scholar Vrajvallabh Śaraṇ of Vrindaban’s Śrī Sarveśvar Press, who had been publishing articles propagating his own Nimbārkan sectarian viewpoint. Śaraṇ’s rival edition was published the following year, in 1966. In turn, Khān responded with a defense of the court’s Vallabhan stance in his own long delayed edition published from New Delhi by Kendrīya Hindī Nideśālay in 1974.Footnote 51 All this careful work on the Hindi literature has been neglected to a large extent in the art-historical publications in English, which ended up foregrounding Dickinson’s pioneering role and largely ignored the challenge to the court’s Vallabhan stance.Footnote 52

Given his academic degree in English, it is not surprising that Khān made comparisons with Western art movements, just as Dickinson had done. He too characterized Indian art as essentially spiritual, foregrounding Rajput art’s “mysticism” (rahasyavād) based on bhakti literature (2015: 288–93). Khān described Nāgarīdās’ literary output and the matching paintings as part of an Indian version of Romanticism (2015: 310). He worked hard in his Hindi thesis to connect Nāgarīdās’ nature descriptions with the “subjectivity” of the Romantic movement, all the while taking care to distinguish them from the stylistic Rīti-like nature descriptions that he deemed more “classicist” (especially 2015: 334–5). Instead of Coomraswamy, he preferred to quote the British Principal of the Government School of Arts in Calcutta E.B. Havell. In a 1975 article, Khān brought up the Mona Lisa comparison that had been left unarticulated by Dickinson. Khān reminisced that back in 1943. Dickinson would send him queries regarding the real model for the Kishangarhi school’s distinctive facial features. One of the English teacher’s suggestions was that she might have been the dancing girl portrayed in a painting Moonlit Music Concert of Sardar Singh by Amarcand (see Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015: plate 2) but it became clear that the painting was too late to have been formative in the school’s development. Khān commented, “The idea of tracing the original of Radha, however, obsessed Professor Dickinson” (1975: 84). In July 1944, Dickinson sent Khān a questionnaire that was further probing as to the model for the Rādhā portrait, so Khān stated, “It is just possible that he [Dickinson] wished to establish a Mona Lisa parallel in the field of Rajput painting” (1975: 84).Footnote 53

Dickinson did not live to publish his findings in book format. It was left to the new director of the Lalit Kalā Akademi (established in 1954), the prolific Parsi art connoisseur Karl Jamshed Khandalavala, to publish and elaborate on Dickinson’s draft. In his capacity as editor of the prestigious Lalit Kalā Series, he edited and expanded Dickinson’s work and published it as a posthumously, coauthored volume on Kishangarh paintings in 1959.Footnote 54 Khandalavala went further than Dickinson had in the earlier paper of 1950. He reverently put the God Krishna down as Sāvant Singh’s first love but posited also a more mundane love in the prince’s life (Reference Dickinson and Khandalavala1959: 8).

Khandalavala was the one who identified the model for the Kishangarhi Rādhā as one of Sāvant Singh’s concubines, known as Bani-ṭhani. He believed she was the woman shown in a painting published in the 1959 volume as The Poet-Prince and Bani-Thani (plate 2, p. 23).Footnote 55 Khandalavala actually attributed this identification to a suggestion by Khān, though the latter would later change his position.Footnote 56 Connecting the identification of the lady in the painting as Banī-ṭhanī with Dickinson’s theory of the real-life model for the Kishangarh type, Khandalavala speculated, “If Nāgarīdās was the creator of this type, then who was the model who inspired him? Surely, it would not require much imagination to conclude that it was Bani Thani” (1959: 9). He was careful to qualify in a footnote, “The truth in all probability is that the Kishangarh type is an inspired idealization, based on a living model, skillfully employed to alter the existing female types already in vogue” (9–10). In the writeup of the “Lady with Veil” (published as plate 4 in the volume), adding to Dickinson’s comparison with the quatro-cento artists, Khandalavala brings in the comparison with the Mona Lisa, “What a triumph of profile treatment is here! In European art surely one would have to go to the achievements of the quatro-cento for any parallel to equal it, or to the great Leonardo himself and his famous Mona Lisa” (26).

Khandalavala’s “inspired idealization” represented a compromise between the eternal ideal type and the realistic influence of a particular individual woman. The characterization of the artistic intervention is tied up with the idealized interpretation of the love relation between the prince and his concubine, as described in rhapsodic words:

Theirs was a love like that of which the bards had sung in tales of long ago. And in the consummation of this love, Nagari Das merged into Krishna and Bani-Thani into Radha. It was a consummation that had no hint of heresy for their way of pleasure was in truth the way of the grace of God – the Pushtimarga of the Vallabhacharya sect. It is not always easy to understand this erotic-cum-spiritual complex, and in fact it is often misunderstood.

Dickinson’s aesthetic preoccupations come through underneath the somewhat apologetical reworking by Khandalavala. He sets straight Dickinson’s misunderstanding of “the way of pleasure” There is a defensiveness about the erotic aspect of spiritual love. Later in the book, Khandalavala asserted:

Thus the great period of his [Nihal Chand’s] finest work under the influence of Nagari Das appears to be between 1735 to 1757… it was during this span of time that masterpieces … were produced. It is not surprising that this very period synchronizes with the passionate attachment of Savant Singh for Bani Thani …. It is fairly evident that neither the patron nor the artist was content with the prevailing pictorial treatment of the Krishna theme. They both sought to transcend the norm for such paintings and achieve what was beyond the pale of mere competence …. In this endeavor the high-souled, exquisite Bani-Thani became their greatest inspiration. In her image they fashioned the divine Radha and everything beautiful in womanhood. It seemed as if the distilled essence of all that the sringara poets had sung lay in this lovely creation. Thus, not only was a new female type created, which became characteristic of all Kishangarh painting even during the 19th century, but a new approach to composition and colouring was also envisaged by Savant Singh and his atelier.

In this formulation, art and appreciation for real-life beauty are intrinsically intertwined. What is remarkable is how little room was made for Banī-ṭhanī’s agency, notwithstanding Khandalavala being aware of her own authorship. While she was acknowledged as an inspiration, it was the patron and the painter who “fashioned the divine Radha and everything beautiful in womanhood.” No sooner had the role of Banī-ṭhanī been identified that she was rendered passive, inspiring, yes, but ultimately merely because she embodied the image of beauty in womanhood.

To support his thesis, Khandalavala was keen on finding textual evidence. Again with the acknowledged help of Khān, he located a passage were Nāgarīdās would describe the traits of Rādhā in terms of Banī-ṭhanī’s distinctive features (Dickinson and Khandalavala Reference Dickinson and Khandalavala1959: 4). As he put it in the brochure accompanying the folio album of Kishangarh painting published in 1971, “In [Nāgarīdās’] poetic description of the milkmaiden who became the adored of the Blue God he has in truth described the loveliness of his own mistress” (1971: 1). Navina Haidar, in her insightful discussion of the theory about Banī-ṭhanī as model, has rightfully pointed out a flaw in this logic: Many poems by Nāgarīdās express formulaic traits of the Goddess, the earliest ones composed long before Banī-ṭhanī came to Kishangarh (2004: 128, fn. 16). This weakens Khandalavala’s argument. The references to curved brows over drooping lotus-like eyelids, and elegantly curling hair locks are indeed standard fare, not just in Nāgarīdās’ poetry, but Krishna bhakti more generally. Yet the poem Khandalavala cites adds a more specific reference, namely to the long nose, compared to a cypress. That comparison is not formulaic, yet it is one of the further characteristics of the Kishangarhi facial type. Khandalavala translates:

What was the original poem underlying Khandalavala’s translation? The cypress-like nose is referenced only twice in Nāgarīdās’ collected works. One is from Braj-sār:Footnote 57

Like Khandalavala’s English version, this poem progresses from the eyes and brows compared to lilies and bees, to the distinctive nose likened to the cypress, ending with smiling flowerbed-like lips. The “dove” might be a free translation for khañjana or “wagtails” in the last line of the Hindi poem. Strikingly, in his translation, Khandalavala left out the first line of the poem with its reference to the veil, which actually would strengthen his argument as it fits the image of “Lady with Veil” so well.

This is a passage from Nāgarīdās’ technical Rīti style work from his 1742, Braj-sār. This textbook of poetics has definitions in Dohā and examples in Kavitta meter. It illustrates all types of nāyikās, but this one comes under the heading bīrī daināntara priya badana ika ṭaka rījha citaibo barnanã (description of unblinkingly staring enchantedly at the beloved’s face, right after providing betel). It seems to be an example of the hero, rather than the heroine. Still, the poem matches the “Lady with Veil” painting with its references to the veil at the outset, the curved brows and eyes, the lock of hair, and especially to her particular style of earring (also omitted in Khandalavala’s translation). In addition, the lotus imagery of the poem is made manifest in the painting through the lotuses in the heroine’s hand. Only the hero staring at her is absent, but possibly this was only the right wing of a diptych that included a portrait of Krishna on the left wing, similar to the later matching set in the National Museum (Mathur Reference Mathur2000: 114–17, figs. 30–40, acc. no. 63.813–4). It seems highly likely then that this is the poem Khandalavala had in mind. And one wonders whether it was inscribed on the back. Nāgarīdās’ Rīti work lends itself well to illustration; in fact, another of its verses (the preceding Kavitta 31) is actually inscribed on the back of a painting by Nihālcand on the theme of lovers exchanging betel, similarly showing the exaggerated profile associated with Banī-ṭhanī (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015: 165–7). To clinch the argument, the poem actually refers to Rādhā; it is remarkable that Khandalavala missed that too in his translation.

The other reference to the cypress-like nose is from a poem in Nāgarīdās’ collection of Festival Poems, or Utsav-mālā. Like the Braj-sār poem, this poem also uses the extended metaphor of the garden for the woman’s body:

Crucial to understanding the initial intent of this poem is the ritual context of the Sāñjhī festival, the autumnal flower festival celebrated by young girls, “tweens,” in between child and young woman. There is a painting attributed to Nihālcand on the theme of Sañjhī that illustrates the features mentioned in the poem (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2015: 181–3). Like the previous poem, it fits Khandalavala’s English version, in its description of the face from forehead to lips, so this is another candidate for what he translated, though he does not mention the autumnal fesival.Footnote 60 In any case, Khandalavala was definitely onto something as he singled out the unusual reference to the cypress-like nose to make his point of the facial characteristics of Kishangarhi Rādhā being celebrated in Nāgarīdās’ work.

Whatever one might think of its worth, Khandalavala’s argument that Bani-ṭhani’s distinctive profile was the model for the paintings convinced many in the art world. The conjecture took on a life of its own and became hardened into “common wisdom.” The review of the Lalit Kalā Akademī book by noted art historian Stella Kramrisch for Artibus Asiae, lyrically summarized, “Nagaridas saw Bani Thani with the transforming eye of mystic; in ecstasy and, feeling one with her, his features echo hers …. He sees Bani Thani, as the essence of herself, aetherialized as Rādhā” (1961: 69). The connection with the Kishangarhi facial type was reiterated in subsequent influential generalizing works, each one contributing a bit more certainty to the original postulation. The keepers of Islamic and Oriental Antiquities at British Museum respectively, Douglas Barret and Basil Gray,Footnote 61 went a step further than “inspiration,” as they wrote about the “small court” of Kishangarh that “produced by a minor miracle the most important school of eighteenth-century Rajasthan painting.” They asserted that “There seems little doubt that Savant Singh’s identification of the two passions of his life [Krishna and Bani-ṭhani] was responsible for the small but magnificent group of pictures painted at Kishangadh between the early years of his love affair and his abdication,” speculating that Nihālcand’s “new and very beautiful type for the divine lovers” was “perhaps based on the features of Bani-Thani herself; though idealized it has the feel of an individual experience” (1963: 155–9). Similarly, curator and art historian Philip Rawson in his popularizing volume on Indian art succinctly proclaimed, “There can be little doubt that the reality of the royal love-affair was a special stimulus to the artist to ‘realize’ in his work the divine prototype.” He is slightly more circumspect in the caption for the “Lady with Veil” image in declaring it, “perhaps an idealized image of Bani Thani” (Rawson Reference Rawson1972: 148; my italics). Thus, Khandalavala’s theories were enthusiastically promoted in subsequent secondary literature.

All this was much to the dismay of the Kishangarh court, whose spokesperson Khān himself authored a rebuttal in 1975 in the journal Roopa-Lekha. While credited by Khandalavala for the identification of the lady in the painting of “Nāgarīdās doing pūjā” as Banī-ṭhanī, he professed having promptly discouraged the theory of Banī-ṭhanī as model for Rādhā. These reservations were taken seriously, among others, in the influential book on Kishangarh Painting by Mohinder Singh and Doris Schreier Randhawa. They were circumspect about the Banī-ṭhanī theory:

Bani Thani … was a beautiful girl who also professed interest in Hindi poetry. She became Sawant Singh’s mistress. It is conjectured that the bloom of her youth and beauty not only roused unholy thoughts in the hearts of men who saw her, but also provided inspiration to the Kishangarh artists, to whom credit is given for the invention of the Kishangarh facial formula …. Khandalavala was of the view that the Radha of the Kishangarh School was modelled after Bani Thani …. Bani Thani provided inspiration to artists by her beauty, but she was not the model for the figure of Radha.

Banī-ṭhanī is somewhat grudgingly acknowledged as an inspiration, but an unholy one, and her influence on the Rādhā portrait is strongly denied. Her authorship is reduced; she simply has “professed an interest in Hindi poetry.” The Randhawas also signaled some distance from the Mona Lisa comparison, stating “the portrait of Radha by Nihal Chand … represents the Rajput ideal of feminine beauty at its best. Those who delight in parallels with western art call her the Indian Mona Lisa” (Randhawa and Randhawa Reference Randhawa and Randhawa1980: 9). Thus, the Randhawas qualified their statements, likely influenced by the stance of the Kishangarh Court.Footnote 62

The matter remained contested. About a decade later, the Jaipur-based painter Sumahendra tried to reconcile the court’s denial of the romance by acknowledging the relationship between the prince and the performer, while simultaneously rendering it more chaste: “we can leave aside the so-called fabricated stories but can not deny their nearness. They loved each other may be like intellectual friends or having sentiments other than lovers. Their love could have been respectable rather than illegal. Pious rather than erotic” (1995: 38). Many less careful secondary sources followed suit sanitizing the romance by turning Banī-ṭhanī into a queen. Only a few noted the court’s and Khān’s reservations to the model theory.

In conclusion, the concept of Banī-ṭhanī as the La Gioconda-like model for Radha–Kishangarh appears to be a hybrid construct, resulting from a complex engagement of colonial and Indian scholars, just like the idea of the “bhakti movement” itself (Hawley Reference Hawley2015). It came about through multiple dialogical interactions between Western and non-Western agents, through mediations, collaborations, confirmations, and contestations. Dickinson’s curiosity may have been a catalyst, but the influential director of Lalit Kalā Akademī, Khandalavala, was the first to formulate the theory that Banī-ṭhanī was the model for the Kishangarhi Rādhā. While Dickinson had compared it with among others Italian art, Khandalavala was the one who first brought up Mona Lisa. Faiyāz ‘Alī Khān may have been instrumental in setting these scholars on her track, but later did his best to refute their theories. Mostly, the relationship between the prince and his concubine continued being characterized as a love affair or passionate attachment, even as Khān issued a sharp denial of a romantic engagement as well as of Banī-ṭhanī’s role as model. While discomfort with the equation of erotic and spiritual love remained, the consensus stressed how Sāvant Singh and Nihālcand together designed the new Kishangarhi type, inspired by, but with minimal agency of Banī-ṭhanī. Throughout all of this, very little attention was paid to the actual poetry of the prince or his concubine. The interpreters of Khetanchi’s canvas discussed in Section 1.1 were following a well-trodden path.

1.5 From India’s Spiritual Face to Cyber-Orientalist Love Story

However one evaluates Dickinson’s contribution to the Indian Mona Lisa trope, he surely put Kishangarh on the art history map. He also bequeathed India a more material legacy; this took the form of a donation from his own collection. The new National Museum’s permanent collection was based on what had been displayed during the grand “Masterpieces of Indian Art” exhibition held in 1948 in Government House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan) in Delhi to celebrate independence. This in turn had grown out of the assemblage of artefacts on their way back to diverse Indian institutions and collections from an exhibition at Burlington House in London that had been organized by the Royal Academy of Arts (November 1947–February 1948; Guha-Thakurta Reference Guha-Thakurta2004: 176–7). The London show had included artefacts on loan from British museam and private collectors that did not travel to India (Codrington et al. Reference Codrington, Irwin and Gray1949: 35–44). To fill the gaps, new loans were acquired for the Delhi occasion, among others a total of 241 items from Dickinson’s personal collection, second only to the Treasurywala collection (and later the Sarola collection; see Banerjee Reference Banerjee1992: 29). A substantial part of Dickinson’s loans was made up of Gandharan sculptures from the North-West,Footnote 63 though his main contribution to the museum collection consisted of paintings, mostly Krishna devotional scenes. While he contributed samples from practically all Rajput schools, the catalogue did not specify, simply classifying as “Rajasthani.” Only the first of the Rajasthani paintings in the catalogue, an illustration of a manuscript of Keśavdās’ Rasik-priyā, is explicitly said to have been acquired from Kishangarh (Agrawala Reference Agrawala1948: 45, no. 386). Further included were illustrations of Bihārī’s famous Satsaī, as well as of the Rajasthani epic Ḍholā-Mārū, and a Rāga-mālā series. One painting is marked as Vāsaka-sajjā, but the dimensions do not match the Kishangarhi “Lady with Veil” (Agrawala Reference Agrawala1948: 48, no. 414). These generous contributions by Dickinson bolstered the new nation’s pride, complicating further his perceived role as the promotor of orientalist tropes about Kishangarhi painting.