The mayor is having a party. A retired bureaucrat, his cohort’s amicale, or social club, is holding its quarterly meeting and it is his turn to host. The mayor’s guests are among the West African state of Senegal’s first generation of postcolonial civil servants and, now retired, they have scattered, some remaining in the country’s urban centers while others, like the mayor, have returned to their natal villages. They pass the day recounting old tales and praising their host on a squeaky PA system, pausing only to share copious plates of rice and mutton. The mayor’s compound also teems with extended family members, neighbors, local government councilors, village chiefs, and one visiting researcher, me. Looming large among the local guests is the village chief of the local government’s chef-lieu, or capital village, a few kilometers to the south. Circulating in a grand white boubou, the chief plays the role of a second host, welcoming guests in between long, reciprocal exchanges of compliments with the mayor. Anyone with a passing familiarity of the local political terrain knows that the two are allies. If the chief can be credited with helping the mayor win the 2014 local elections, then the mayor is currently repaying him by bolstering the former’s claim to his village’s chieftaincy in the face of a challenger. Though not without criticism, theirs is no doubt a mutually lucrative alliance.

Herein lies the crux of the two political conflicts animating the local government in early 2017: the mayor narrowly won a first term in 2014, but his predecessor remains in the local council’s opposition, either playing the role of gadfly or opposition party leader depending on one’s perspective. Meanwhile, in the local government’s capital village, the village chief’s politically prominent extended family is beset by internal divisions over which branch of the family can rightfully claim the chieftaincy. Neither conflict is hidden for those who are in the know, but if one is not, the mayor’s party – and the community more broadly – appears peaceful and harmonious. On all fronts, one local government councilor concludes that things proceed “like normal.”Footnote 1 Indeed, there has never been – nor will there likely be in the near future – a grand political explosion. Rather, these conflicts simmer under the surface, beneath cordial greetings, and carefully protected reputations, kept in check by social norms that prioritize consensus and community stability.

This presents a puzzle to dominant theories of redistributive politics. After all, why would one of the most outspoken members of the opposition party vehemently argue that it was his duty to support the current mayor, for “without our support, it will be hard for the mayor to do any good in the community. So, we support him because we know this is the only way the community will go forward”?Footnote 2 I argue that such statements are not puzzling once we take into account the fact that the mayor’s party is taking place in the heart of the Cayor. This chapter deploys two case studies to refine our understanding of how and why communities reach different redistributive solutions under decentralization, comparing the mayor’s historically centralized local government – “Kebemer” – with an otherwise similar but historically acephalous local government – “Koungheul” – located a few hundred kilometers to the southeast. These model-testing case studies allow me to probe the theory’s mechanisms with more precision than is afforded in the survey data or quantitative analysis presented thus far. At the same time, by spending an extended amount of time in each community, I was able to collect a more complete inventory of local government projects than that examined in Chapter 5, facilitating additional tests on the theory’s observable implications.

Following a discussion of the case selection strategy and methodological overview, I introduce the cases of Kebemer and Koungheul, detailing how the mechanisms of shared local identities and dense social network ties among elites are present in Kebemer, but absent in Koungheul. The consequence is that shared social institutions net almost all of Kebemer’s elites into reciprocal, cross-village webs of obligation that alter the behavior of politicians by encouraging them to adapt more prosocial attitudes toward the group. In contrast, politicians in Koungheul report being far less constrained in their behavior, rendering local government redistribution targeted and representation uneven.

I then introduce an “off-the-line” case of “Koumpentoum,” which has a mixed history of precolonial centralization. Despite falling within the territory of the kingdom of Niani, the political fortunes of which declined dramatically at the start of the nineteenth century, Koumpentoum illustrates that institutional congruence is dependent on the social reproduction of social institutions over time. Because current residents descend from lineages that arrived after the onset of colonial rule, Koumpentoum’s current population was never exposed to the state of Niani. As a result, the local government lacks cross-village social institutions, rendering it more similar to acephalous Koungheul than centralized Kebemer. The chapter concludes with a short discussion of alternative explanations.

Case Selection and Methodology

I employ a paired case analysis to develop insight into the theory’s mechanisms. To do so requires selecting cases that are similar in as many respects as possible apart from their exposure to a precolonial polity. I follow a “typical” or on-lier case selection strategy from the analysis of the village-level infrastructure investments made in the 2000s presented in the previous chapter.Footnote 3 Following Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2005), I sought two well-predicted cases to help refine my understanding of the mechanisms animating my theory, ideally ones that displayed extreme scores on the independent variable, which can be a useful method for discovering potential confounders.Footnote 4 I further sought an “off-the-line case” where I would expect congruence yet where exposure to a precolonial state does not appear to impact local governance today. To do so, I zoom in on the experience of precolonial states that had collapsed prior to French colonization.

To arrive at my final selection, I deliberately winnowed the pool in four ways. I first eliminated all cases I had already visited for the survey conducted in 2013. The choice was secondly constrained by my desire to visit a third local government, one that fell in the territory of a precolonial state that did not persist into the late 1880s. Together, these first two criteria left a relatively limited pool. Because we might hypothesize that different ethnic groups possess distinct norms that could influence local governance, I prioritized ethnic match as a third criterion. Lastly, I sought cases that were comparable on other factors likely to be influential, such as geographic zone, economic activity, and the level of social service access at the onset of the 1996 decentralization reforms.

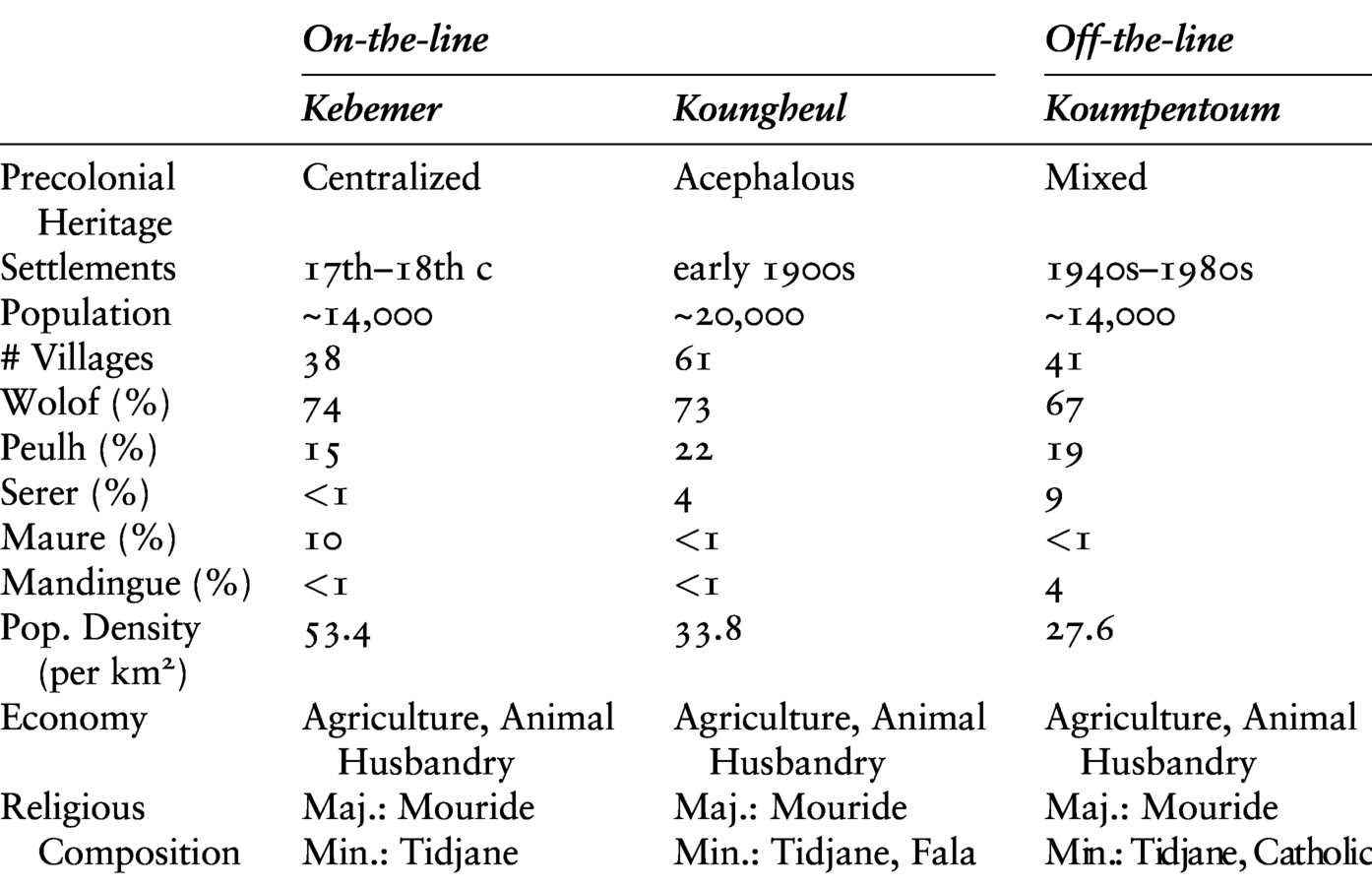

Combined, this means that the three chosen cases were the most comparable cases within these parameters. The selected cases are similar on key political dimensions as well: their partisan alignment with the central state has been in lockstep since 1996, they are all home to numerous villages with strong ties to the Mouride and Tidjane Sufi Brotherhoods that dominate Senegal’s Islamic practice, and the ethnic majority in each is Wolof. Of course, this is never a perfect exercise; centralized Kebemer’s population is both lower and more densely inhabited, though it still falls far below the national average for historically centralized areas of 102 residents per square kilometer. Further differences were found once I arrived on the ground. Koungheul had fifty-one villages listed in the official village repertoire that I had obtained in Dakar, but I soon learned that ten new villages had been created by the previous mayor (though, as I will detail below, this itself proves to be valuable data for my argument).

Descriptive information on the selected communities can be found in Table 6.1, where I also offer a comparison with the third case of Koumpentoum introduced in the chapter’s second half.

Table 6.1 Description of case selection

| On-the-line | Off-the-line | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kebemer | Koungheul | Koumpentoum | |

| Precolonial Heritage | Centralized | Acephalous | Mixed |

| Settlements | 17th–18th c | early 1900s | 1940s–1980s |

| Population | ~14,000 | ~20,000 | ~14,000 |

| # Villages | 38 | 61 | 41 |

| Wolof (%) | 74 | 73 | 67 |

| Peulh (%) | 15 | 22 | 19 |

| Serer (%) | <1 | 4 | 9 |

| Maure (%) | 10 | <1 | <1 |

| Mandingue (%) | <1 | <1 | 4 |

| Pop. Density (per km2) | 53.4 | 33.8 | 27.6 |

| Economy | Agriculture, Animal Husbandry | Agriculture, Animal Husbandry | Agriculture, Animal Husbandry |

| Religious Composition | Maj.: Mouride | Maj.: Mouride | Maj.: Mouride |

| Min.: Tidjane | Min.: Tidjane, Fala | Min.: Tidjane, Catholic | |

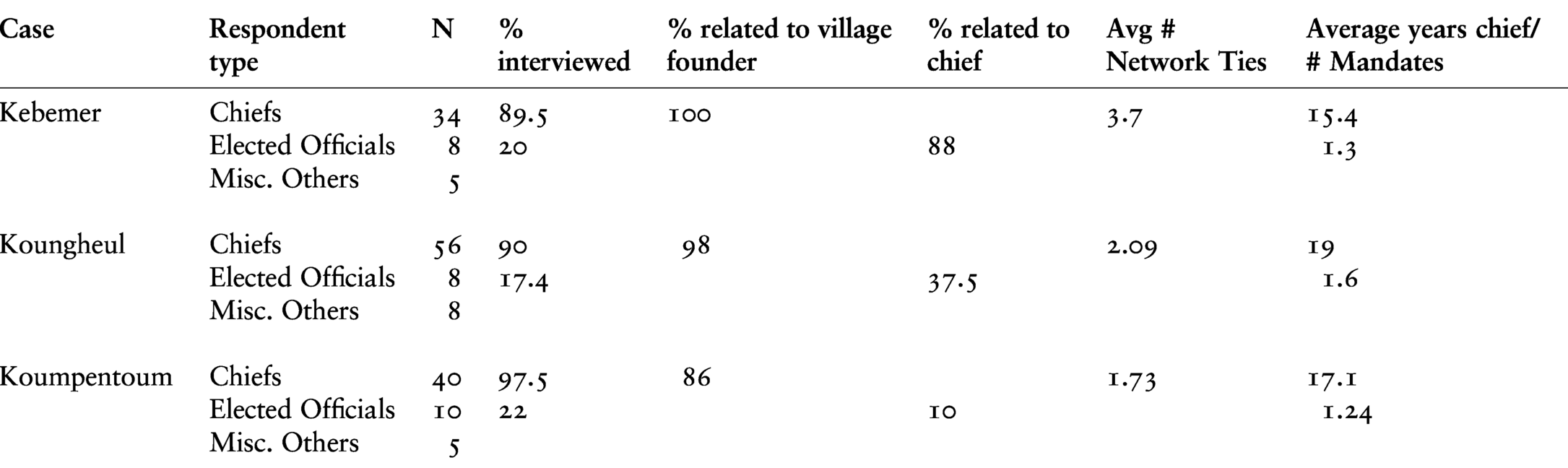

The research was conducted with the help of two Senegalese research assistants during an approximately two-week stay in each local government. Open-ended interviews were conducted with a large swath of local elites, during which we posed a series of questions about the history and demographics of their villages as well as what they had received from the local state and when. We discussed local political life, including the most recent local elections (held in 2014) at length, asking politicans about their entrance into politics and political campaigns while village chiefs were asked about their experience with local state politics. The only standardized part of the interviews came at the end when we collected social network data for each respondent, inventorying their social ties to other elected officials and village chiefs in their communities, categorized as acquaintances, friends, extended family members, or immediate family members (e.g. a daughter-in-law or brother).

Table 6.2 presents descriptive statistics on the entire sample of interviewees. Though the objective was to speak with as complete a list of village chiefs as possible, this was not achieved in any local government, primarily due to chiefs traveling or being too ill or old to be interviewed. Nonetheless, nearly 90 percent of chiefs were interviewed in each case. Repeated interviews were conducted with the mayor of each local government in addition to one if not both of the mayor’s adjoints. Beyond this, we sought to speak to five to six local councilors, with priority given to local opposition party leaders. Because I was interested in local governance since 1996, I additionally interviewed former mayors and councilors who had served multiple mandates on the local council. A number of village chiefs in all three communities noted that they had previously served as councilors as well. When possible, I also met with other state agents, including the subprefect and local development agent in each arrondissement, griots (traditional praise singers) who recounted the community’s history and the secretary posted by the central state to each local government.

Table 6.2 Descriptive statistics for case study interviewees

| Case | Respondent type | N | % interviewed | % related to village founder | % related to chief | Avg # Network Ties | Average years chief/ # Mandates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kebemer | Chiefs | 34 | 89.5 | 100 | 3.7 | 15.4 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 20 | 88 | 1.3 | |||

| Misc. Others | 5 | ||||||

| Koungheul | Chiefs | 56 | 90 | 98 | 2.09 | 19 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 17.4 | 37.5 | 1.6 | |||

| Misc. Others | 8 | ||||||

| Koumpentoum | Chiefs | 40 | 97.5 | 86 | 1.73 | 17.1 | |

| Elected Officials | 10 | 22 | 10 | 1.24 | |||

| Misc. Others | 5 |

These more formal interviews were paired with the informal interactions that arise when one stays in a small community, conversations with neighbors who stop by to introduce themselves, with state agents who pass through the local government, or with the horse cart and motorcycle drivers we hired to transport us to different villages. Consequently, while the stay in each local government was too short to be considered ethnographic, each case offers a snapshot of the political debates and evaluations taking place within each community at the time of research. To preserve the anonymity of respondents, I have changed the names of respondents and identified each local government by the department – a higher-level administrative unit – that it falls within. Because Senegal’s administrative units are named after their capital city, I identify the capital village (or chef-lieu) of each local government as, for example, “Kebemer-Village.”

As with the survey data presented in Chapter 4, I was cautious about priming respondents to discuss the precolonial past. Accordingly, I instructed my research assistants to not explicitly raise questions about this period until a respondent did, asking more generic questions about their village’s foundation instead. Across interviews, we heard largely consistent narratives within each local government. Indeed, in many cases, respondents inadvertently cross-validated each other. For example, villages founded in new territories such as Koungheul often engaged in chained patterns of migration; arriving in a new zone, individuals would seek a “host” in an existing village before founding their own settlement nearby in the following years, once a well had been dug and fields plowed. These entwined histories of settlement were always told on both sides: in the village that first hosted newcomers and in the villages that the newcomers went on to settle.

Of course, the risk that these stories were inflated remains, but the shared nature of their telling remains important even if the facts stray into local mythologies. In this way, the stories I heard reflect a localized process of meaning-making as much, if not more, than an accurate retelling of history. We could, however, imagine that in an age of autochthony debates, individuals may claim to an outsider, such as myself, that their village is older or that it played a particularly weighty role in local history. Yet I saw no such opportunism. Indeed, recently founded villages were often headed by the founder himself or, at times, a son, both of whom would detail with pride their village’s founding story. Though many of the stories recounted below are likely inflated and partially reimagined, therefore, I have little reason to think that they are invented de novo.

At the time of research, all three local governments were facing a common set of structural challenges. First, local councils struggled with the realities of President Sall’s Acte III of decentralization, introduced in Chapter 2. Though this had earned them the titles of commune and mayor, many were disappointed with the reforms, which had done little to alleviate the most central concern of local elected officials: finances. Yearly fiscal transfers had only barely increased, officials noted, yet they were being asked to take on more responsibilities at the same time that local populations had come to expect more activity at the local level.

This was further complicated by President Sall’s second major initiative, Le Plan Senegal Émergent (PSE), a medium-term plan designed to transform the country’s economy. For local officials, the felt consequence of the PSE was the elimination of a number of state programs that had previously provided fiscal transfers for local governments that, though earmarked by sector, granted the local council full autonomy over their use. While yearly transfers of the FDD, the financial lifeline for local governments, remained constant, Sall introduced instead the United Nations Development Program co-sponsored Programme d’Urgence de Développement Communitaire (PUDC), effectively removing local control over program funding to centralize it in the prime minister’s office. This is not without benefit for rural livelihoods. The PUDC is focused on large-scale investments such as roads and boreholes that are far beyond the means or competency of the local state. But local officials elected in 2014 found themselves with a significantly reduced set of fiscal assets than their predecessors. This was widely recognized; across all three cases, local councilors, village chiefs, and other stakeholders observed a sharp decline in local government activity.

At the same time, Senegal’s rural mayors were working within a weak and fragmented local party structure. Echoing a common story of the 2014 local elections, the communities were animated by political jockeying within the relatively weak Presidential majority coalition, Benno Bokk Yakkar (BBY) or, alternatively, within Sall’s own party, the Alliance pour le République (APR). The consequence was the splintering of lists within the party itself, meaning that some voters saw multiple lists from the same political camp on their ballots. In many cases, for example, the APR ran lists against their own coalition, BBY. This reflects, in part, a long-standing tendency toward intraparty factionalism in the country, but it speaks more immediately to the weak structure of the relatively young APR at the grassroots.Footnote 5 While the previous ruling parties, the long-ruling Parti socialiste (PS) and the Parti démocratique sénégalais (PDS), maintained robust local party apparatuses, few rural areas had a meaningful APR presence until Sall’s election in 2012, which prompted significant bandwagoning to the majority party by elected officials and village chiefs. As detailed below, this meant the outcome of the 2014 elections was not a given for any candidate in the cases under study.

Each case under study had seen a new mayor elected in 2014, and together the three factors detailed above meant they all found themselves facing unforeseen top-down constraints on the resources at their disposal and bottom-up constraints imposed by weak local party structures. Despite these similarities, however, I document below three very different outcomes for local governance.

Assessing the Theory in Kebemer and Koungheul

I introduce the cases of Kebemer and Koungheul by focusing on the three component parts of my theory: the (a) identity and (b) network mechanisms that sustain (c) cross-village social institutions when both are present. The section “Representation and Redistribution across Social Networks” goes on to compare why the presence of social institutions that encompass the majority of villages enables local officials in Kebemer to better overcome the social dilemmas they face in the local council.

The Identity Mechanism

Kebemer is the home of the mayor at whose party this chapter opened. Despite being erected as a local government in 1976, few local elites discuss Kebemer’s history as if it was a mere forty-years-old, placing local history firmly within a legacy of the Cayor Empire, a major precolonial state in the Senegambian region.Footnote 6 During the era of the Cayor, most villages in the kingdom were highly stable social units, linked together through clientelist ties, shared histories, and mythology.Footnote 7 Evidence collected during my stay suggests that these patterns have persisted and residents widely expressed great pride in the shared heritage they believed their community represented. Indeed, the mayor, Alou Gueye, welcomed me first and foremost to the “heart of the Cayor.”Footnote 8

The community’s uncontested founding narrative was that the zone had been settled over 400 years earlier by five families who had departed the Djoloff Empire, under which the Cayor had long been a vassal.Footnote 9 Together, each family had founded their own village, with their descendants expanding to establish new settlements over time.Footnote 10 As a result, most villages in the community traced their descent from one of the five founding lineages and 85 percent of community’s villages were settled before the onset of colonial rule. Of the handful created after 1880, only three were established by in-migrants with no ties to the zone. Because of this shared descent, the local government is dominated by the Wolof ethnic group, the ethnicity of four of the five founding families, though one of the Wolof families was casted. The remaining founding lineage was ethnically Maure. These families had been joined during the precolonial era by Peulh pastoralists, whose settlement in the zone created friendships and reciprocal ties between “new” and “old” villages, reflecting a broader pattern in the kingdom which was home to Mandingue, Maure, Peulh, and Serer minorities.Footnote 11 Now, one Wolof chief said of his Peulh neighbors “we are the same family.”Footnote 12

The identity of a shared descent from the Cayor generated a commonsense framework that individuals drew on when describing their community. Most residents shared a deep respect for their history and were extremely hesitant to betray this common identification.Footnote 13 In particular, a prominent role was played by the shared claim to the final resistance thrown up by the Cayor as the French advanced into Senegal’s interior; “this is a historic zone,” one village chief explained, “we always resisted the whites with Lat Dior [the last king of Cayor]. We are not cowards.”Footnote 14 As the local development agent explained that “this history is still very powerful here … everyone’s ancestors were involved.” As articulated by the former mayor in no unclear terms: “these century old relations gave [Kebemer] a historical consciousness and identity.” The history may have been bloody, he continued, but the impact today is only positive.Footnote 15 The current mayor, one chief noted, won in the 2014 local elections explicitly because he had successfully “played the card of unity,” highlighting his descent from a prominent, aristocratic family rather than seeding partisan competition.Footnote 16

The second case, Koungheul, is located to Kebemer’s southeast in Kaffrine Region which falls in the eastern stretches of Senegal’s peanut basin, the epicenter of the country’s cash crop production. Prior to French colonization, Koungheul was acephalous, home to a sparse population living independently outside the control of a centralized polity. In an 1896 report, an early colonial administrator described the region by what it was not rather than what it was: “For the commodity of language, I designate under the generic name of ‘Coungheul’ the group of heterogeneous cantons … bordered to the west by the Saloum, to the north by Djoloff …”Footnote 17 Densely forested and primarily inhabited by nomadic Peulh pastoralists in the precolonial era, no existing village in the local government was founded prior to 1900. The first wave of modern implantation occurred in the early years of French colonization and many chiefs recounted how their grandparents had spent years clearing the land, digging wells, and, in many cases, fighting off wild animals that inhabited the forest. These settlers searched for new land for their families and herds, seeking to escape overcrowded villages and the social upheaval generated by the early stages of colonial occupation.Footnote 18 In other cases, marabouts (Islamic religious guides) moved to the area to found Dahiras, or Koranic schools, away from French interference. More recent waves of implantation came as Peulh herders settled in the area, in particular following the droughts of the 1970s and 1980s.

Unlike in the Cayor, stories of settlement in Koungheul are largely specific to each village, though in some cases clusters of villages shared a unifying settlement history. For example, one maraboutic village had been the initial point of arrival in the zone for the families that went on to found a number of surrounding villages. In this way, these villages possessed a group identity – their shared allegiance to the marabout – but it encompassed only a small percentage of villages in the local government. Across the local government as a whole, no narrative about what it meant to be Koungheulese was heard. This is revealed in the comments of a retired school director who explained that the local government capital, Koungheul-Village, had long reclaimed that the mayor be from their village, since they had only held city hall once. Being administered by mayors from other villages is “like a technical administration always coming here to rule us,” he sighed.Footnote 19 Social identities are present in Koungheul, therefore, but they are splintered across villages within the local state.

The cases of Kebemer and Koungheul echo many of those presented in Chapter 4. The availability of a shared history of descent from a precolonial kingdom united Kebemer’s villages into a cohesive local identity that revolved around the glory of the Cayor. Because no comparable touchstone was available in Koungheul, no overarching political identity emerged, with individuals attached to their villages, religious leaders, or their ethnic groups. Koungheul, in other words, is a case of multiple, sub-local government identities.

The Network Mechanism

Local social network ties also differed across the two cases. Again and again, elected officials and traditional authorities in centralized Kebemer claimed that these very family relations and shared histories of cohabitation had generated a “mentality of solidarity,” thus that whenever political disputes arise, everyone moves quickly to protect local social relations.Footnote 20 In contrast, interviewees in Koungheul reported pockets of social connections between villages whose grandparents had migrated together to settle or, as in the case of Peulh pastoralists who had settled in the area, connections built through intermarriage over the past half-century.

Preliminary evidence for the network mechanism was found in the survey data presented in Chapter 4, but the case studies offer a means to test this more robustly. I collected the reported social ties of each village chief and elected official interviewed. Though individuals’ social networks extend far beyond the borders of the local government, I bound the network to villages and councilors within the local government. This meant that I asked each village chief if they personally knew the chief of each village in the local government and, if so, how they would describe their social relationship. I additionally asked each village chief if there was a councilor from their village or if there had been since 1996 as well as their relationship to these individuals. Later, I more generally asked if they were related to any other political actors in the local government to catch any missed connections. Because I only interviewed approximately 20 percent of elected officials in each local government, I primarily rely on reporting by chiefs about their connections with the councilors in their village.Footnote 21 Though respondents at times disagreed over whether or not they were friends, no one identified someone as family without their pair reciprocating that identification.Footnote 22

Figure 6.1 displays the extended family ties between village chiefs in each local government as a baseline for intervillage connectivity. Each node represents a village chief in the network, with ties between nodes indicating a reported relationship between them. Figure 6.1 displays these ties categorically by the nature of reported relationships, either extended (e.g. second cousins) or immediate family (e.g. sibling, uncle, or in-law).Footnote 23 Figure 6.2 displays friendship ties. Nodes are disaggregated by ethnicity in both Figures 6.1 and 6.2. Lastly, Figure 6.3 compares reported relationships between village chiefs and councilors (disaggregated by gender) who were serving at the time of research (meaning those elected in 2014), with nodes color-coded by village of origin.

(a) Kebemer

(b) Koungheul

Figure 6.1 Family network relations between village chiefs.

(a) Kebemer

(b) Koungheul

Figure 6.2 Friendship network relations between village chiefs.

(a) Kebemer

(b) Koungheul

Figure 6.3 Network relations between village chiefs and local elected officials.

The networks look starkly different. In Kebemer, the social network is largely well-connected and centralized, with all but one village reporting multiple family ties to other village chiefs. While there is some indication of ethnic segmentation, there is evidence of intermarriage across villages. In contrast, we see clustering effects in Koungheul where a densely connected subnetwork of small, Peulh villages have heavily intermarried (though three villages of Peulh in-migrants from Guinea report no family ties at all). Wolof and Serer elites remain loosely connected. Friendship ties, seen in Figure 6.2, show slightly more centrality in Koungheul. Nonetheless, a large number of village chiefs report no friends in other villages at all, and across both family and friendship networks, acephalous Koungheul displays a much larger number of isolated or near-isolated nodes. This has no parallel in Kebemer, where all elites report at least one family and friendship ties, and most report multiple ties of each type.

These dynamics are particularly acute when we examine the relationships between village chiefs and elected councilors; here the centrality present in Kebemer across local elites is clear. As displayed in Figure 6.3, one clear network appears in Kebemer. Koungheul likewise has a central cluster, but we see the presence of far more weak connections at the edges. Nearly one-third of villages are not connected to another village at all, though a few report connections to their village’s own councilors. Together, these network plots reflect what comes out in the interviews. Social networks in Kebemer are more coherent and interconnected than those in Koungheul, where network centrality clusters within ethnic groups while a number of villages report weak or nonexistent social ties.

How the Mechanisms Support Cross-Village Social Institutions in Kebemer but Not Koungheul?

Respondents in Kebemer repeatedly invoked shared social expectations for public life. As norms of appropriate behavior in the public sphere demarcated by group boundaries, social institutions rely on dense social networks and strong identities to motivate individuals to adhere to their logic. Actors abide by any given social institution both because they perceive costs to not doing so and because they think to do so is proper or good. Parallel to those identified by survey respondents in Chapter 4, social institutions in Kebemer were most frequently invoked along two axes. The first is around conflict resolution and prevention, most often discussed with reference to the concept of “democratie de palabre,” or democracy by ongoing discussion. The tradition of community leaders sitting together to discuss an issue until they find a mutually agreeable solution echoes the practices described by Schaffer (Reference Schaffer1998, 80). Writing on Senegal’s Wolof heartland, Schaffer argues that Senegalese peasants and rural elite think of democracy not just as electoral practice, but as reflecting “consensus, solidarity and evenhandedness.” This was reported widely in Kebemer. As phrased by one chief in Kebemer, “the tradition of discussion has always been the secret behind our social force.”Footnote 24

The broader manifestations of this norm had direct bearing on local political practice. The declaration of the former mayor of Koungheul that politics is “a confrontation like chess” could not be in sharper contrast to the position of Mar Ndaw, Kebemer’s former mayor, who argued that even someone who is your enemy today could be your ally in the future so it was best to not risk offending them. Explicitly citing the cost to local social relations, local elites in Kebemer all boasted that they would never call in the police or state agents to resolve disputes; “even if there is a complicated problem, we call the mayor. We will do everything to not call the police.”Footnote 25

This “mentality of solidarity” serves to prevent the escalation of conflict and, when it does arise, to protect the reputations of those involved.Footnote 26 Kebemer’s former mayor, Ndaw, reported going to great lengths to resolve potential points of conflict, especially when applying the law may adversely impact family members. “I would prepare the terrain, talking to people and informing them,” he recalled, working through trusted intermediaries, such as village chiefs, notables, or mutual friends, when the situation called for it. He continued, “you cannot just impose things … Especially when you are related, you have to go with humility, know-how and then be willing to work with them” on any given issue. Such practices are not only time-consuming, he acknowledged, but they limited his political choices.Footnote 27 Social networks, in other words, were directly cited as shaping political strategies. “Politics is complex,” one elderly chief in Kebemer recalled, but no matter how complicated, “you should never do things that dirty your family name and you should certainly never damage family ties for the sake of politics.”Footnote 28 Here we see clearly how the theory’s twin mechanisms are activated to reinforce powerful social institutions that constrain political strategies.

Such informal institutions exist everywhere and almost all village chiefs in rural Senegal describe one of their central obligations as “guarding social stability in the village.”Footnote 29 But it is only in communities like Kebemer that they stretch across villages to encompass the vast majority of elites. Consequently, cross-village, extended family ties were sacrosanct in Kebemer, but they were not so in acephalous Koungheul. “In politics, there is no family,” stated Koungheul’s former mayor acerbically.Footnote 30 Indeed, his local government illustrated this well: the current and former mayors were cousins, but they were also engaged in a bitter, ongoing rivalry within the same political party. Some in their large, extended family scolded both men for creating tension in the family and others stayed clearly in one camp or the other, but most prioritized keeping peace with their relatives, noting that “we are family and everyone has problems sometimes.”Footnote 31 Locally understood and institutionalized norms of resolving conflicts are not specific to Kebemer, therefore, but who they apply to – a village, an extended family, or, as in the case of Kebemer, to all descendants of the Cayor – differs.

The second influential social institution in historically centralized areas is the prioritization of balancing across group members. It was quite rare in Kebemer to hear complaints of favoritism; most village chiefs, for example, thought that the local government recognized each village’s needs without attention to ethnicity or caste and without ignoring smaller villages. This was not explained as a function of democratic ideas, but rather to the idea that the local government’s constituent villages had equal claim to its resources by virtue of their shared history.

While individuals noted equality as an aspirational goal in both communities, it was only in Kebemer that local elites spoke of their government as actually attaining it. In Koungheul, it was quite common for individuals to argue that officials should fight narrowly for the interest of their own village. The description of one chief’s ideal candidate for local government in Kebemer as “a good leader for the municipal council is someone who puts everyone on equal footing and who works hard” is at odds with a common response in Koungheul, “the councilor should help the population of his village and defend them in the council.”Footnote 32 If in Kebemer local elites had all embraced the value of equality among villages, elsewhere elites had either internalized the comparative inequality they lived under or had learned that their villages and clients would never get anywhere if they waited for the local council to bring it.

Social Institutions in Action: Evaluating the 2014 Local Elections

The dynamics of institutional congruence are illustrated with particular clarity in the outcomes of the 2014 local elections. Both local governments saw the defeat of the incumbent mayor by a relative newcomer to the political scene, yet while the consequences of this upset continued to generate political tensions in Koungheul, they had largely been papered over in Kebemer.

In 2014, Kebemer saw Alou Gueye, running with the new Presidential Coalition, BBY, defeat the two-term incumbent, Mar Ndaw. As introduced at the start of the chapter, Gueye was a recently retired bureaucrat who had returned to the local government as a vocal ally of the president. Ndaw had been elected twice with former President Abdoulaye Wade’s PDS and ran again with the PDS in 2014. Both men were educated and came from locally prominent families. Ndaw was considered to have done much for the local government, investing broadly and prolifically, but he faced a difficult contest with Gueye, who was seen by many as a potential asset given his experiences in the bureaucracy. In line with social institutions of balancing, the sentiment prevailed that it was only fair to give someone else a chance; as one chief reasoned about the choice to vote for Gueye over the incumbent Ndaw, “Ndaw already served two mandates and the population thought they should give it to someone new.”Footnote 33

The election was incredibly close. Gueye’s BBY coalition only won with the help of the nearly unanimous support of a large Peulh village, run by an influential marabout. Two details of Senegal’s electoral system are key to understanding the political intrigue that followed. Senegalese political parties run a majority and a proportional list and if a party wins, all of the candidates on its majority list pass as well as the equivalent percentage of their vote share on the proportional list. In Kebemer, the sitting mayor, Ndaw, had made the usual move of placing himself at the top of the proportional list (“I take this as a sign he knew he couldn’t win,” his successor jabbed) and was accordingly elected into the opposition. A second peculiarity of Senegal’s local elections is that local government leadership, the mayor and his two adjoints, are only elected indirectly by members of the new council following the general elections. This means that even though Ndaw’s party lost the majority, he was still eligible to be elected mayor, which, in fact, he tried to accomplish by recruiting votes from three councilors elected under Gueye’s APR lists. Upon learning of this betrayal within the APR, Gueye sensed that his candidacy was imperiled, leading him to go back on a campaign promise that his first adjoint would come from his coalition partners in the Socialist Party, promising it instead to a member of a nonaligned minority party as a means to buy himself the three necessary replacement votes. The move worked, but it continued to raise eyebrows three years later.

Communities like Kebemer are clearly not without political conflict. Politicians want to win, and they will pursue this at length. What is distinct, however, is the degree to which community members bound these interactions. Though heated at the moment, therefore, political memories in Kebemer are uniquely muted. When probed about the three councilors’ betrayal in 2014, for example, Gueye dismissed my questions, stating that he “had forgotten all that and who voted for whom.”Footnote 34 Ndaw concurred, observing that the community had “barriers” to who can become one’s enemy or adversary. “We are here amongst ourselves,” he explained, continuing “the lead-up to elections is the time for politics … afterwards, everyone returns to their work since everyone knows everyone else.”Footnote 35 The outcome is not collective amnesia. Individuals speak with relative openness of past disagreements, but they embed them within social ties. Admitting that he sometimes disagrees with friends and family in the local government, one former councilor and current advisor to the mayor explained that this simply could not take priority. “Other relationships are stronger, more important than the council,” he stressed.Footnote 36

Koungheul also saw a political betrayal in 2014. Like Kebemer, Koungheul had elected the majority Wolof local government’s first Peulh mayor, Mamadou Dia, with the PDS in 2002 and again in 2009. In 2014, Dia’s cousin and a sitting local government councilor, Abdou Balde, challenged him in – and ultimately won – the local elections. Though Dia had been elected to both terms with the PDS, like many mayors he had joined the APR in 2013. This understandably upset his cousin, who had himself been preparing to run with the APR, only to find himself cast aside by departmental APR officials who believed that Dia was a more promising candidate. Angered, Balde quit the party and approached the PDS who, interested in obtaining a well-known and, not inconsequentially, wealthy candidate to their camp, quickly altered their electoral list to accommodate him. In what to many was a surprise victory, Balde beat his cousin by running with the latter’s former party. And within just days of his election under the banner of the PDS, Balde rallied to his former party, the APR, to bring himself and many of the candidates elected with him into the Presidential majority.

In Koungheul, family ties did little to smooth over Dia and Balde’s mutual dislike and both men reported virtually no social contact. In direct contrast to the frequently heard desire to protect social relations in Kebemer, a councilor in Koungheul stated in no unequivocal terms that “family doesn’t play in politics.” What differs is that in Koungheul, no cross-cutting social institutions have emerged to check the political repercussions of both old and new political divisions. “Well,” concluded one of village notable, “politics is like this. A friend today can become your enemy tomorrow.”Footnote 37 This lesson, in turn, had been learned by Mamadou Dia who was still visibly angry over his cousin having ousted him in 2014.

The 2014 elections created a number of lingering political tensions. The residents of Koungheul-Village were anxious to elect a member of their own village as mayor, yet despite having a strong candidate on the PDS list, many Wolof councilors from the village defected at the last minute to support Balde for mayor because their village’s own candidate was a member of a lower social caste. Prominent elites in the village, the mayor explained, could not bring themselves to vote for someone whose grandparents had danced and sung for their grandparents, a reference to the casted councilor’s descent from griots.Footnote 38 As the local government secretary stated early in our first meeting, “the Wolofs here do not get along and the Peulhs profit.”Footnote 39 The heated political campaign in 2014 still actively colored political allegiances in Koungheul in the winter of 2017. Dia remained the local APR party coordinator, protected by his close friendship with the party’s departmental leader, much to the chagrin of Balde, who felt that the position should be his as mayor. Rumors swirled. One councilor, loyal to Dia was skeptical “he [Balde] says he rejoined the APR, but I heard he may be with another party ….”Footnote 40

Though we may be tempted to understand Koungheul’s politics as ethnic, this would be a simplification of the situation. At base, what divides the local government is those who lament the departure of Dia, who was a strong patron to those who supported him, and those who have rallied behind Balde, who struggles to deliver to his supporters. Both men actively report their first political objective as rewarding their core supporters, no matter their ethnicity or caste, reflecting an ability to politicize social network ties opportunistically. This stands in stark contrast to the prevailing rhetoric in Kebemer, which emphasized putting electoral rivalries aside and working for the good of the local government specifically to preserve social relations.

Representation and Redistribution across Social Networks

If social institutions vary in the degree to which they embed local officials across villages, then this should create different solutions to the redistributive dilemmas generated by decentralized governance. I examine this in two issue areas, village representation on local electoral lists and, second, local government public goods delivery over a fifteen-year period between 2002 and 2017.

Representation

The goal of improving representation is central to democratic decentralization. Beyond its value in its own right, facilitating the ability of local citizens to voice their preferences is among the most desired of decentralization’s many claimed benefits. Citizens who feel represented by the state should see the state as more legitimate and hold their governments more accountable to help make governance more efficient.

This makes allegations of bias and neglect – such as one village chief in acephalous Koungheul’s statement that the local council “has never taken care of us, even though we are part of the municipality too” – all the more troubling. The village had never had a councilor and, according to the chief, every village had been helped but his.Footnote 41 The latter statement was factually untrue, but the perception among villages that they were singled out and treated as lesser community members has profound consequences for state consolidation at the grassroots. When communities feel that “we are only there to elect them and nothing else,” it is not surprising that, over time, some segments of the population disengage from their local government.Footnote 42

The easiest measurement of these dynamics is found in discussions of electoral list construction. “It’s very hard to make party lists,” the former mayor of Koungheul stated. “There are those who can do the work well, but do not have a mass [followers] behind them, and then there are those who do not know how to work, but who have a mass with them,” and in this case, he continued, you have to take the latter.Footnote 43 The practice of seeking candidates with influence – be it in their village, with area women or youth, etc. – is common around the country, but deciding which villages obtain candidates is another question altogether.

In Koungheul, these decisions were recounted as being bitter and deceptive. It was not uncommon for village chiefs to report that party leaders had promised to put someone from the village on their party lists, leading villagers to declare their allegiance for and campaign with the party, only to find on election day that their village’s candidate had never been on the list at all.Footnote 44 Such deception was not easily forgiven. The village chief of Koungheul-Village reported with pride that he had taken his horse cart across the local government to campaign against Dia in 2014, explicitly stating that his endorsement of Balde was to spite Dia, who had promised the chief a spot on the 2009 PDS electoral list, only to omit his name once the official lists were posted.Footnote 45 Though lists are often made during meetings with all local party officials, it was widely agreed upon in Koungheul that “once the leader is alone, they can change the names.”Footnote 46 Smaller villages or those that felt disadvantaged spoke of this process as compounding their inability to get anything from the state. “Party leaders just pick people who will follow them,” stated one disgruntled chief.Footnote 47

Such contention is largely absent in centralized Kebemer, where respondents by and large tell a similar tale of how lists are made: party leaders go to villages looking for influential people, often by consulting with village leaders. Once a list of potential candidates is in hand, the party decides how many councilors to take from each village (largely according to village population) and then consults with the village to help narrow down the list of potential candidates. Invoking the community’s dense networks, Kebemer’s mayor reported that making electoral lists was not very hard at all (“we all know each other after all”), and they simply proceeded by asking each village to put forward names of influential and qualified people. While the mayor admitted to having given the chef-lieu more spots than he would have otherwise – only to face an unexpectedly tight competition there – most villages were assigned as many spots on party lists as their population merited.Footnote 48 Certainly, this does not mean that everyone is content with the number of councilors they receive, but most accepted that this followed local norms of maintaining balance across villages. Importantly, when grievances were voiced, village chiefs engaged in a form of excuse-making prevalent in historically centralized areas. Noting that his village had not had a councilor in years, even though he always asks for one, one chief quickly suggested that this was probably because his village had moved closer to a larger village home to their marabouts a few decades before. “They likely don’t consider us our own village anymore, since we are so close …” he observed, noting that the marabout’s village did have a councilor who he considered to represent his village’s interests.Footnote 49

Redistribution

Perceptions of bias and favoritism are not only more prevalent in historically acephalous areas, they are also sharper, neatly articulated along locally demarcated political cleavages. In contrast to the 6 percent of chiefs who made any allegation of unequal treatment by the local government (for their own village or others) during the course of the interview in Kebemer, 57 percent alleged some form of inequality in Koungheul. Even chiefs who did criticize the local government of Kebemer reflected norms of conflict avoidance by excusing such behavior. For example, one chief whose village had not been among those to receive a solar panel for their mosque was not sure why his village had been left out. Invoking a norm of equality, he argued that if most villages were receiving something, then all villages should do so, though he caveated that the fact that his village mosque already had a solar panel might have something to do with it.Footnote 50 Still, across the board, respondents in Kebemer reported that distributional choices are “not overly political” the way they might be elsewhere.Footnote 51 More often than not, village chiefs and councilors had a clear understanding of why things were placed where they were, revealing how information circulated within their dense social network: to take a few illustrations, “[the recipient village] is a large village, so it is normal that the health hut there was rebuilt”; the council “tries to look for which village is the most needy and the situation of neighboring villages”; “we know each other, we may all have the same needs, but we also know whose needs really are urgent.”Footnote 52 In Kebemer, redistributive choices were widely seen as fair and following a sufficiently transparent logic.

There was also little debate over how things were distributed in acephalous Koungheul: the political allies of the mayor are given priority eight times out of ten, contended one chief, an equation he claimed was true of the current mayor as well as his predecessor.Footnote 53 Some had been favored under one administration, but consequently ignored by the next. For this reason, another chief expressed skepticism that the current council would ever repair his village’s broken water pipeline since he had served as a loyal councilor with the previous mayor for two terms.Footnote 54 Even the most basic interactions with the local government, including the delivery of birth, marriage, and death certificates, were subject to political interference. Koungheul’s former mayor was widely reported to have denied signing any etat-civile paperwork (such as birth or marriage certificates) for villages that did not support him. One councilor, a local health agent, reported that it had been nearly impossible for her to get birth certificates for newborns in her village, “Mohamadou Dia [the previous mayor] didn’t like the village because, even if he had a few followers in the village, most of the village was not with him. He wanted all of the villages … so he blocked our paperwork as punishment.”Footnote 55

Technically, delivering paperwork is not a devolved competence, but it is the most burdensome task that the local state is charged with, requiring extensive hours of copying and recopying paper records of all declared births, deaths, and marriages. The incoming mayor, who had served as a councilor in the previous term, said he had processed thousands of état-civile requests since taking office.Footnote 56 All children who wish to enter primary school must present a birth certificate, and denying birth certificates for children for more than a year after birth requires a more elaborate – and expensive – process later on. The most frequent interaction that most rural Senegalese have with the local state involves état-civile paperwork and for many, it is their only interaction. Despite this, one of Koungheul’s chiefs surmised that the politicization of this most bureaucratic of tasks was not surprising; “Mohamadou Dia was always in campaign mode, when he knew that your village wasn’t with him, he did nothing for you.”Footnote 57

Politicians are acutely aware that they need to deliver “development” to their constituents if they wish to win reelections. Despite the restricted financial resources he had to work with, for example, the mayor of centralized Kebemer proudly recounted the many things he had accomplished in his term, including an ongoing project to digitize the état-civile, rebuilding a health hut, the construction of a new vaccination center for livestock, remodeling an old community building where he planned to put a library as well as the aforementioned solar panels, and the purchase of six millet mills introduced at the start of the book. By and large, Alou Gueye followed the strategy of balancing outlined by his predecessor: the latter explained that he had explicitly targeted villages that had not voted for him when he first took office, recognizing that “I would lose later if I didn’t work with everyone” and that one was “first and foremost a development agent as the PCR [mayor] and a leader should not leave people out or put politics before development.” As a result, Ndaw had spent a little more than $9,000 bringing water to a large village he had lost during his first campaign in 2002. “They are still very happy with me there,” he laughed.Footnote 58

This strategy was not universally shared. In contrast to Kebemer, where the mayor had yet to deliver anything to his own village, politicians in Koungheul frequently made such investments. For his part, Koungheul’s mayor stated that the most pressing need in his local government was to build a new health post in the village immediately neighboring his own, even though they were only 6 kilometers from the post in Koungheul-Village, far closer than the local government average. His first act, he reported, was to bring water to two villages where more than 95 percent of the polling station had voted against him.Footnote 59 But this telling was incomplete. The mayor had in reality brought a pipeline to his own village and, as clarified by one of the chiefs whose village also received a connection from the pipeline, “even he [the mayor] wouldn’t dare not give it to the villages along the way.”Footnote 60 In a now-familiar story, Koungheul’s former mayor, Mohamadou Dia, said his proudest accomplishments after ten years of service were bringing water to his village and those surrounding it, as well as building a health post a few hundred meters from his compound and, in a particularly costly endeavor, grating a new road between the chef-lieu and the village immediately adjacent to his.Footnote 61

I map the projects delivered to each village by the local government over the past fifteen years in Figures 6.4 and 6.5. The same data are calculated per capita in the second panel to account for village size. Together, these network plots validate the themes in the qualitative data – there is more evidence of clustering in Koungheul as opposed to Kebemer where projects are redistributed more evenly across the network. Numerically, slightly over half of Koungheul’s villages report receiving an investment since the passage of Acte II in 1996, in contrast with nearly 90 percent in Kebemer.

(a) New public goods

(b) Percentage of new public goods as percentage of pop share

Figure 6.4 Kebemer public goods delivery.

(a) New public goods.

(b) Percentage of new public goods as percentage of pop share.

(c) New village creation.

Figure 6.5 Koungheul public goods delivery.

Figure 6.5c also shows a unique form of “redistribution” in Koungheul, where the former mayor, Dia, had created nine new villages for his extended family members over the course of the term. Obtaining the status of an official village is highly desirable since being an official village both entitles one to certain central government deliveries, such as seed and fertilizer before the growing season, as well as better positioning a community to make claims on the local state.Footnote 62 This is not uncontroversial. Allowing part of a village to effectively “secede” or recognizing a preexisting hamlet as an official entity in its own right often violates local social standards over who is the rightful claimant to both symbolic goods, such as standing in the community, as well as material ones, notably land. In a political strategy that created loyal allies to the present, Dia’s solution to family feuds was simply to create new villages, but it was also a means by which he could punish his political opponents by reducing the population under a rival chief’s authority. Many mocked these new villages – “it’s a village of three houses,” one chief joked when we told him we were headed there next, before sighing “politicians, they create enormous difficulties for us.”Footnote 63 Though Balde, the current mayor, had publicly decried Dia’s strategy, he himself had created one new village in a move that many saw as a comparable reward to his supporters.

Evaluating a complete inventory of projects delivered in Kebemer and Koungheul since the onset of decentralization corroborates the findings presented in Chapter 5. The politics of institutional congruence generates incentives for politicians to deliver broadly across space and, in line with these expectations, we see Kebemer’s elected officials distributing projects across the community irrespective of ethnic or political affiliation. In sharp contrast, redistribution is more targeted in Koungheul, with some villages favored at the expense of others according to explicitly political criteria.

States without Legacies: The Example of Koumpentoum

The paired case studies of centralized Kebemer and acephalous Koungheul demonstrate how the legacy of precolonial statehood in the former generated social institutions around balance and social harmony that stretch across villages, carrying them into contemporary politics following decentralization. To further illustrate that it is these mechanisms and not some other, unobserved feature of regions that were able to support precolonial polities that generated these differences in contemporary political performance, I include an “off-the-line” case, one that is not well-predicted by the model, but which is ostensibly similar to Kebemer and Koungheul on most dimensions (see Table 6.1) apart from its precolonial history.

The local government of Koumpentoum falls in the territory of the Mandingue-dominated precolonial state of Niani, which rose by consolidating power as an intermediary in the Atlantic slave trade, controlling slave routes from the Upper Senegal Basin and Guinean highlands to the coast. Unlike other states that more adeptly pivoted their economic orientation following the abolition of the Atlantic trade in 1807, the Niani saw a sharp decline in fortunes.Footnote 64 As the state lost dominance of its territory, the region of present-day Koumpentoum saw near complete out-migration of residents of the Niani. New settlers arriving in the early twentieth century claim abandoned wells as they established new villages in the Niani’s ruins. In contrast to the long histories of centralized Kebemer, the majority of Koumpentoum’s villages were founded following independence. As a consequence, neither the identity nor network mechanism from the Niani has reproduced social institutions for the local government’s residents.Footnote 65

Like Kebemer and Koungheul, the 2014 elections saw the victory of the APR and the defeat of two terms of PDS rule, though in this case the incumbent mayor had stepped down. The winner, Daouda Diallo, was a state agent who, though not originally from the region, had long worked in the arrondissement. Diallo made much of the fact that he was educated – which neither his predecessor nor his immediate competition was – a strategy that was quite persuasive to the population who thought that a literate mayor would improve their livelihoods. But “now people feel fooled.”Footnote 66 Diallo had repeatedly and quite openly admitted to “eating” the local government’s meager tax revenue and was accused across the board of a “nebulous” management of the commune’s resources. Halfway through the council’s term, the local government was at an effective standstill. Factionalism in the ruling APR was rampant, leading one opposition councilor to observe that “there is almost no party.”Footnote 67 Particular evidence of the mayor’s political weakness was seen in the fact that he had lost his own village, the local government capital, in the country’s 2016 constitutional referendum, widely interpreted as a barometer of support for his party.

Koumpentoum as a Case of Institutional Incongruence

Why is such political dysfunction present in Koumpentoum despite falling in the territory of a precolonial state? I argue that Koumpentoum is a case of institutional incongruence because it lacks both mechanisms necessary to carry cross-village social institutions from the past into the present. Because the zone saw significant out-migration in the nineteenth century as residents on the Niani left the territory, the village-based social hierarchies that I identify as the mechanism of persistence for social institutions were abruptly displaced. Although in-migrants established new status hierarchies in their villages, these do not trace their legitimacy or claim to territory to the era of the Niani, meaning that there is neither a shared sense of identification nor sufficiently dense social network ties among elites to embed the majority in cross-village social institutions capable of constraining elite behavior.

This is illustrated clearly in the pervasive corruption allegations made against the mayor. When asked about missing funds during the annual budget meeting, the mayor attempted to defend himself by claiming “I will not tell anyone the details of why the process is delayed, I am not going to run away, we live here together!”Footnote 68 In Kebemer, such narratives of cohabitation are potent, pulling local political crises back from the brink to preserve family ties and reputations. But in Koumpentoum, councilors merely laughed and doubled down on their critiques. The perception among local elites was that they could not effectively sanction the mayor because he had weak social ties to the zone. “Really, it’s the commune’s fault for electing someone who is not from here,” began one chief, “why would he care if the commune advances or not? He has no family here … so he can do whatever he wants because his family does not suffer, and they do not know.”Footnote 69

The splintered nature of social ties had ramifications beyond Diallo alone. The community was defined by its distinct waves of settlement which generated village-based identities, meaning that Koumpentoum lacked all but the weakest of cross-village identities. The head nurse of Koumpentoum’s health post surmised this neatly, “people are not proud to be from Koumpentoum … people have to be proud to live here for things to get better. But, up until now, no leader has done this, has tried to make ‘Koumpentoum’ a meaningful entity.”Footnote 70 Disengagement became the standard response. “The mayor doesn’t work, there is nothing to say to or about him,” dismissed one councilor, an attitude reflected in the fact that the local council was reported to be regularly below the required quorum as councilors lost interest.Footnote 71

Critically, the lack of cross-village social institutions meant that no unified effort to counter Diallo’s rapacious behavior emerged. In contrast, the ensuing political debate was over who could best succeed him, a question that reignited the local government’s long-standing rivalry between its three largest villages. Babacar Diouf, a dynamic, educated young councilor from the largest village had surprisingly won five seats for his small party in the 2014 elections and was one oft-mentioned contender. As the son of his village’s first candidate for mayor in 1984, residents of the Koumpentoum-Village did not mince words in expressing their distaste for Diouf, even though he had gained substantial popularity among the small villages in the local government’s neglected southeast. “[Koumpentoum-Village] thinks I am looking for revenge,” he noted, “they think I am out to trick them as payback” for my father’s loss in 1984.Footnote 72

Figure 6.6 replicates the family and friendship networks between village chiefs in the local government and between chiefs and councilors. As is immediately obvious, family ties are much weaker between elites; social networks here are more tree-like, relying on single connections between elites rather than the multiple and reinforcing connection seen in centralized Kebemer and within subsets of Koungheul’s population. While there is more centrality in friendship ties, nearly half of chiefs report two or fewer friendships with other chiefs in the local government.

(a) Family network relations between village chiefs.

(b) Friendship network relations between village chiefs.

(c) Network relations between village chiefs and local elected officials.

Figure 6.6 Elite networks in Koumpentoum.

Representation and Redistribution in Koumpentoum

As predicted by my theory, Koumpentoum as a case of institutional incongruence displays representational and redistributive patterns more akin to acephalous Koungheul than centralized Kebemer. Allegations of unequal treatment were made by three-quarters of the local government’s village chiefs and coalesced most clearly around local government work. The majority of villages reported confusion, concern, or outright ignorance on why they received nothing while others, in their view, were favored by the local government. The most common comment was a variant of “the mayor distributes things by affinity and appreciation, there is nothing clear in how he runs things.”Footnote 73 On this issue, the numerous villages along the local government’s southeast border were indisputably neglected; “us, the small villages, we are not considered by the commune. We fulfill our obligations to the council [e.g. pay taxes], but they have never done anything for us even though we have over 250 residents,” argued one chief.Footnote 74 Here the effects of not having a councilor were perceived as compounding the ability of the council to ignore certain villages. “Villages like [name], [name], [name] which have a lot of councilors are the ones with influence here … they have people to defend them in the council.”Footnote 75

As was introduced for Kebemer and Koungheul in the introduction to this book, Koumpentoum also purchased and delivered three millet mills in 2016.Footnote 76 The first mill went to a small village of approximately eighty residents, the second was delivered to a village that had a mill run by a private operator, and the third went to the mayor’s own village, already home to three functioning mills. Recalling the council meeting where the choice of villages had been announced and forced through to a vote, a village chief laughed with dismay, “there was a lot of conflict that day … that meeting did not follow any standards.”Footnote 77 For his part, the mayor justified the choice as one of ethnic balancing: an ethnically Wolof, Peulh, and Serer village had each received a mill. Even if we accept this as a legitimate criterion, the mayor himself explained that he had carefully chosen from among all possible Wolof, Peulh, and Serer villages those that had most actively supported him in 2014.Footnote 78 As one councilor aligned with Diallo laid bare, the party’s approach was to take need into account, “but if the village is not with the mayor, we will not do anything.”Footnote 79

As in Koungheul, this favoritism impacted even the most basic of local government duties. One opposition councilor in Koumpentoum noted he had more than fifty requests for new identity cards in his briefcase, the result of Senegal’s adoption of biometric identity cards for the approaching legislative elections a few months later, but the mayor had been delaying signing them for weeks, requiring the councilor to travel back and forth to the chef-lieu. “They say he is sick,” the councilor confided, “but I know he is signing paper for others.”Footnote 80 Critically, there is little evidence that such patterns were specific to Diallo’s administration. As Diallo’s predecessor stated, given three projects, a politician should give two to those who are with you and one to those who are not.Footnote 81

Figure 6.7 illustrates the delivery of new public goods since 2002 in absolute and per capita numbers, respectively. While the largest village had seen four projects, far above the average of 0.8, looking at these numbers per capita reveals the favoritism of the two mayors in power during this period to their mutual home village (and capital) as well as a small number of politically loyal villages.

(a) New public goods.

(b) Percentage of new public goods as percentage of pop share.

Figure 6.7 Koumpentoum public goods delivery.

The case of Koumpentoum offers two critical insights for my argument. First, because the territory was capable of sustaining a precolonial state for nearly 200 years, it indicates that there is not some unobserved variable that both fostered state formation in the past and enables broad redistribution in the present. In contrast, it illustrates the necessity of a mechanism of persistence to carry social institutions from precolonial states into the decision calculi of politicians following decentralization. Because the population of the Niani out-migrated, the local government’s contemporary residents lack robust cross-village social networks to circulate reputations and ensure social sanction for poorly performing behavior. They also hold disparate and competing social identities. The social institutions that prevent political opportunism and conflict in centralized Kebemer thus fail to emerge between villages and local elites because they never existed for the population in question in the first place.

Second, though many village chiefs correctly identified the territory as having been ruled under the Niani prior to their arrival, there was not a single attempt – veiled or otherwise – to claim this history. Rural elites appear to be either uninterested or unable to latch onto a mythology of precolonial glory when they have no credible claim to doing so. In stark contrast, elites in Koumpentoum proudly recount how and why their grandparents settled the zone, revealing divided and atomized village identities, cumulating in disjointed and competing historical narratives. Put otherwise, absent the mechanism of persistence, we do not see opportunistic claim-making to an alternative history.

Assessing Alternative Explanations

A priori, there is no reason to assume that politicians in centralized Kebemer are inherently more benevolent than in acephalous Koungheul or in the off-the-line case of Koumpentoum. Rather, my argument is that politicians in Kebemer inhabit distinct social worlds that reward prosocial behavior while also raising the costs of predatory behavior. Could Kebemer’s broadly redistributive behavior be driven by something else?

Perhaps, for example, the fact that the local government has been dominated by Wolof elected officials has unrecognized properties. Gennaioli and Rainer (Reference Gennaioli and Rainer2007), for example, argue that centralized ethnic groups facilitate greater accountability between chiefs and local populations, relations that have persisted over time. Anthropological evidence abounds that ethnic categories and identities were radically transformed by the colonial encounter, and most precolonial states, in particular those in West Africa, were multiethnic.Footnote 82 But if there are ethnic legacies – say in this case among the Wolof – that facilitate collective action, we may very well expect that any local government run by a Wolof majority would perform better.

This begs the question of why Wolofs – the majority ethnic group in all three cases – were able to politically unite in centralized Kebemer, while in acephalous Koungheul they are described as “lacking a common heart” in contrast to their Peulh neighbors.Footnote 83 The back-to-back mandates of Peulh mayors in Koungheul were explained (with no lack of judgment) by Wolofs as the result of the willingness of Peulhs to “get out their money” to buy votes.Footnote 84 But during Kebemer’s 2014 local elections, both the Wolof incumbent and his Wolof challengers were widely reported to (and indeed admitted to) giving “small gifts” to influential local actors.

Ethnic stereotypes abound in all three cases, but ethnicity is only occasionally how local actors understand the boundaries of their social solidarity. While Wolofs in Koungheul or Koumpentoum were said to “easily divide” along lines of caste or settlement waves, inter- and intra-ethnic relations in Kebemer were described as broadly harmonious.Footnote 85 Listening to local elites reveals more variable understandings of what group boundaries are salient. The Wolofs in centralized Kebemer report feeling tied together through dense family relations and their shared identification with the precolonial past, but critically this category and network encompass most local minorities. I find no evidence that Wolofs have different cultural characteristics than Peulhs or Serers, or that Wolofs are somehow culturally different in Kebemer than elsewhere. Rather, political leaders in Kebemer are constrained in their ability to play with local social relations to win office and, crucially, these constraints cross ethnic and caste lines.

A second alternative explanation is that the varying nature of representation and redistribution reflect patterns of electoral targeting – say of core or swing voters – and nothing more. Certainly, electoral dynamics in historically acephalous Koungheul reflected a clear bias toward a core constituency for each candidate, with larger Wolof villages serving as swing votes. As one nonaligned village chief explained, it was to be expected that the mayor favors certain villages “because some villages supported him and its only normal he would favor them as repayment.”Footnote 86 Little agreement on this strategy emerged, however. Koungheul’s former mayor observed that he preferred to more aggressively pursue votes in swing villages, since “your base is already won,”Footnote 87 but a minority party councilor explained that a politician ought to constantly deliver to their base.Footnote 88

In contrast, core voters were harder to assess in the off-the-line case of Koumpentoum, where politicians’ self-described electoral strategies can be more accurately summarized as reflecting a logic of minimum winning coalition formation. Here, the mayor had established an uneasy alliance to win the 2014 local elections by carefully including candidates from the long-neglected southeast of the local government and by promising key spots to members of each of the local government’s major ethnic groups to ensure that they would get the necessary votes to win.Footnote 89 In the end, he had won with just fewer than 50 percent of the votes, with minority parties splitting the remainder. Since then, villages that had not been in the mayor’s coalition had received nothing from the local state.

Neither dynamic explains the case of Kebemer, where politicians describe their political coalitions broadly and report a relative inability to alienate community members regardless of ethnicity, partisanship, or caste. In contrast, Kebemer’s current mayor’s electoral strategy is easily summed up as a classic turnout strategy. The mayor reported visiting each village to help residents get on the electoral rolls, quickly adding here that it was every citizen’s right to vote and that possessing an identity card was important for rural citizens beyond just elections.Footnote 90 This was largely confirmed by village chiefs. This was eminently political, but it was a distinctly less divisive strategy in comparison to his colleagues in Koungheul and Koumpentoum. As one notable described the mayor, “his party is the locality.”Footnote 91