By the late eighteenth century, a vast number of books were in circulation in the Viceroyalty of Peru, more printed commodities than ever before. Their transmission from production to consumption took place in colonial market structures that fostered some developments and impeded the progress of others. In 1778, the forty-five-year-old Felipe Quiros went to prison in Lima for having traded books without a licence. The titles were neither heretical nor subversive political texts, but of a genre called cartillas, which were used to teach children how to read. It was only the printing workshop of the Orphanage in Lima, the so-called Imprenta de los Huérfanos, that held the privilege of printing and commercialising the small booklets by decree, but violations were repeated over the following decades. Quiros signed a declaration that he had traded in eight gross of the primers, more than a thousand copies, although he knew it was prohibited to buy, sell or use them for teaching.Footnote 1 Cartillas had become such a bestseller on the colonial Peruvian market that trading them was a very profitable business. Various printers and salesmen engaged in the trade even without the required licence. Within a framework of regulations and conditions, the book market offered a platform for the distribution of texts, yet barriers on various levels hampered the free unfolding of the trade.

This chapter is concerned with the context in which the book trade took shape in late colonial Peru and shows how it functioned within certain confines. It argues that the circulation of books, though lively, was constrained for social, legal, and material reasons in the colonial setting, on account of contemporary levels of literacy, the legal frameworks regulating the production and commercialisation of books, as well as the material conditions of printing. The primer (cartilla) was one of the genres that by decree could only be printed in Lima, while most books came via import. In the hope of large-scale business, printers and traders such as Felipe Quiros competed for the trade in small booklets, regardless of the restrictions. As the genre of cartillas thus illustrates, this framework of making and trading printed commodities in Peru can be read as a metaphor for colonial politics and the struggles between the imposed system and its subversion. Although there is a large scholarship on the difficulties of establishing the first printing workshop in Lima and the control of the book trade that created conflicts between civil and ecclesiastical authorities,Footnote 2 historians have focused on single aspects rather than taking into account ‘the whole socio-economic conjuncture’ as such.Footnote 3 As there has never been a case of free circulation of books without barriers, the chapter will take into account the trade’s ‘history of restrictive factors’,Footnote 4 analysing it in a colonial setting.

The chapter opens with an evaluation of the illiteracy that excluded many from direct participation in print culture. Educational reforms by the Bourbons permitted some flexibility in the hierarchically organised colonial society, and alternative ways of acquiring reading skills outside of schools led to a moderate increase in readers. By tracing the case of illegally printed primers, the second part of the chapter focuses on the laws for book production and trading derived from Castile, before addressing the dual mechanism of control on the book market. Due to colonial restrictions, there was no free production or trade in print publications; however, actual practices could subvert the system. The chapter closes, in a third section, by examining the material constraints that held back Peruvian print production, looking at the necessity of importing paper, the practices of ink preparation, and the re-use of types. In the viceroyalty, and despite the fact that the market was still subject to these three barriers, things were gradually changing during the Enlightenment era, and the book trade had begun to flourish.

1.1 Illiteracy

The small-format cartilla was one of the most common genres on the book market, playing an essential role in the acquisition of literacy. Contemporary definitions of the genre can be found in sources that describe it as ‘the primers with which the children learn reading’ as well as its usage ‘for primary education’.Footnote 5 It offers a promising tool with which to study instruction in reading at the time, and Víctor Infantes has termed its frequent use a ‘printed education’.Footnote 6 Still a little-understood subject, education in colonial times has been classified as ‘largely elite, male, private, and humanistic’, as Susan E. Ramírez puts it.Footnote 7 Despite this exclusive tendency, learning at the elementary level took place in an increasing number of primary schools that imparted reading skills to boys and also girls, most of whom were Spanish and criollo, with a smaller number of indigenous pupils.Footnote 8 Literacy practices adapted to the contexts of the viceroyalty and the material possibilities. The focus on the cartilla as a tool thus helps us to better understand the process of learning how to read, both inside and outside educational institutions.

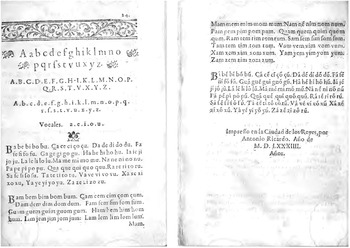

From the early days of printing in Lima, the cartilla was a product of the colonial workshops, and supported the spread of literacy. The first Peruvian cartilla only survived because it was inserted into the Doctrina christiana, y catecismo, printed in Spanish, Quechua, and the Aymara language after the Third Council in Lima in 1584.Footnote 9 It consists of two pages and contains in the first line the twenty-five letters of the alphabet, repeated below in capital letters and lowercase letters, with a separate section for the five vowels, before ending with three blocks that introduce all possible syllable combinations (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Cartilla as part of the catechism titled Doctrina christiana, y catecismo para instruccion de los indios, y de las de mas personas, que han de ser enseñadas en nuestra sancta fé. Con un confessionario, y otras cosas necessarias para los que doctrinan, que se contienen en la pagina siguiente. Compuesto por auctoridad del Concilio Provincial, que se celebro en la Ciudad de los Reyes, el año de 1583. Y por la misma traduzido en las dos lenguas generales, de este reyno, quichua, y aymara. Impresso […] en la Ciudad de los Reyes, por Antonio Ricardo, 1584, 24–24v.

This display of letters and their possible combinations established the starting point for learning how to read, and neither the pedagogical method nor the material presentation or layout changed in the following decades or centuries. The booklets ranged in format from quarto to the very small sextodecimo and in length from two to twenty-four pages.Footnote 10 Of prosaic use and cheap production, cartillas are not preserved in present-day collections of books despite the high number of editions and the many reprints. While bibliographies list only single editions, as in 1735, 1787, and 1803 for Lima,Footnote 11 many archival sources filled with complaints about the illegal trade and requests for printing privileges for primers reveal how extensive and continuous the production must have been, allowing for speculations of today’s historians about a high demand on the book market.

In the colonial period, reading and writing formed two independently taught subjects. At first, a traditional spelling method helped students to learn the rudiments of reading through constant repetition and memorisation, embracing different consecutive steps from the letters of the alphabet to the syllables, and, in the next step, from the formation of words to simple phrases. For this purpose, cartillas served as educational tools, supplemented by syllable books (silabarios), Christian first readers (catones), and catechisms (catecismos), all in line with Christian doctrine. Some titles directly addressed children, while others were composed for teachers, or copies were used for both learning and teaching. Commonly, the process began with the primers and only when the pupil had learned the booklet by heart through repetitive recitation did they proceed to the reading of small sentences and paragraphs, as in the first readers with the basic orations, the Pater Noster, Credo, Ave Maria, and Ten Commandments. For easier reading, syllables were printed separately (Pa-dre nu-es-tro…). Sometimes, in addition to doctrinal prayers and instructions, the catones offered practical life skills including manners and the first rules of arithmetic. After the cartilla and the catón, the catecismo served to teach students about the basic principles of the Catholic faith. These were often organised in a question-and-answer format, as a dialogue between a teacher and a pupil about the basics and mysteries of the faith in the vernacular language.Footnote 12 As recommended in contemporary study plans, the works by Astete and Pouget or the fables of Samaniego helped guide reading classes.Footnote 13 Even in classrooms, the two skills occupied different physical spaces, with the rows of steps for reading separated from the writing desks, as shown in a plan for a primary school in Chachapoyas in Northern Peru (Figure 1.2).Footnote 14

Figure 1.2 Plan of a primary school in San Juan de la Frontera de Chachapoyas in 1782, with a view of the classroom: the letter D indicates the desks for writing with inkwells and seats on both sides, the letter E indicates the rows of steps for reading. [Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañón,] Trujillo del Perú, primer volumen, II, 343, fol. 120r.

Large quantities of the principal textbooks came from Spain, filling the Peruvian market with a massive didactic print offering of religious subjects. The arrival of thousands of such booklets illustrates how large the distribution of educational print publications was in Peru. In 1776 and 1778, for example, two ships from Cádiz came loaded with more than 1,000 dozen: 377 dozen catones and 701 dozen catecismos.Footnote 15 In general, the counting method for these educational booklets was by the dozen. This not only highlights their unique sale value, but also suggests that ecclesiastical institutions were their principal consumers, ordering in bulk at a discount. In Lima, booksellers and merchants had numerous primers in stock, as was the case with Don Juan de Velasquez, who listed seventeen gross cartillas pequeñas and sixty-two dozen catones in his collection in 1770.Footnote 16 Everywhere in the viceroyalty, cartillas were used for learning in the classroom, as exemplified by the priest who asked the Bishop of Huamanga to provide necessary primers for the schools.Footnote 17 If supplies were low, single exemplars were sufficient, of which pupils were to make copies, not on paper as that was often scarce but on blank wood panels.Footnote 18 The large numbers of primers on the market point to an increased customer group who received reading lessons. The learning processes demonstrate that reading skills were by no means equivalent to the ability to sign one’s name, yet only the latter is reflected in most literacy rates.

In the study of the book market, it is the buyer or book possessor who stands at the other end of the trade from the printer, not the reader, though a single person can play both roles. Literacy commonly serves as an analytical tool for analysing the constitution of a potential customer group and functions as the central point of departure for determining the share of active participation in the print world. Highly debated, literacy has been associated with progress and civilisation, and print with being a vehicle for change and revolution, as in the contentious debates about the rise of Protestantism, the Renaissance, or the Scientific Revolution in Western Europe, while the role of reading and the printing press in Spanish America has only been occasionally addressed in this respect.Footnote 19 Historians have generally assumed that the ability to sign one’s name was far more widespread than numeracy and the ability to write, and so most assessments of literacy are based on counting signatures in notarial archive documents, mainly traced through wills and purchasing contracts.Footnote 20 For the signature part, the colonial Peruvian notary files contain standardised expressions. While, for example, a miller signed his last will with the typical clause ‘so he said, conceded, and subscribed in his name […]’, another document has the signature not of the woman who drew up the will but of her substitutes, followed by the explanation ‘so she said, conceded and did not subscribe for being a woman’.Footnote 21 Although in other cases women did sign contracts and wills, in general female literacy rated below that of males.Footnote 22 While they remained low, in the course of the eighteenth century literacy rates for both women and men slowly increased.

Assumptions about general literacy in late colonial Peru are difficult to determine due to the strong gradient between urban and rural areas, as well as to the use of Spanish in contrast to indigenous languages, which are primarily oral. While no statistical study provides data, scattered hypotheses assume a rate of around 20 per cent.Footnote 23 Such a number has to be put into context in relation to factors such as gender and language. Alberto Flores Galindo has estimated that 50 per cent of Lima merchants, thus men, signed their testaments in 1770.Footnote 24 At the end of the colonial period, in the 1820s, barely half of the population, which then measured 1.5 million, used Spanish as their primary language, in contrast to Quechua and Aymara, and only a fifth (20 per cent) of that segment was literate.Footnote 25 At the same time, in the capital alone at least 5 per cent of the male inhabitants could sign their name, as shown by the Declaration of Independence in 1821.Footnote 26 Based on such numbers, literacy rates in colonial Peru lagged behind other areas: in New Spain, for instance, 16 per cent of women and 46 per cent of men were able to sign their names to marriage licence applications.Footnote 27 Data from Spain also shows that rates varied, from more than half of the inhabitants of Madrid (59 per cent) having the ability to sign their name at the end of the eighteenth century to something less than a fifth (20 per cent) of the Spanish population in the same period.Footnote 28 Numbers in the Spanish Empire stood behind many other European places and the much higher literacy rates for British America.Footnote 29

Yet determining such literacy quotients is not easy, and a vast scholarship rightly criticises the binary opposition of ‘illiteracy’ and ‘literacy’, referring to a set of practices, or rather a range of skills. The calculation of literacy rates in the past is a very tricky venture anywhere, and inferences rest mostly on shaky foundations regarding their composition, representativeness, and effects. This must be kept in mind in the analysis of the book market of colonial Peru, especially as there is no correlation between the variables of literacy and participation in print culture. Books could be traded by illiterate cajoneros, who sold out of a stall or a box, or owned and used by illiterate persons too, as will be shown in the following chapters. In addition, increases in literacy did not automatically entail changes in the demand for books. First, literacy numbers as estimated from archival sources reflect a skewed group of people because the sources are not representative of the biased set of persons who have left records, rather than portraying real numbers. Second, rates fail to integrate multiplying factors like the intermediation of writing and reading aloud. Third, even if, for example, an artisan was literate, he perhaps did not have enough disposable income or free time to indulge in non-productive activities such as reading a book.Footnote 30 Therefore, as it is impossible to pinpoint total literacy numbers in the case of colonial Peru, the constant trade in cartillas serves as a pertinent approach to investigate the augmentation of reading skills and invites us to rethink literacy practices in the colonial context.

Another approach to the study of reading skills focuses on schooling and education, both of which expanded in the eighteenth century. Pablo Macera has proposed that about 1,000 (20 per cent) of the 5,000 children living in the capital received primary education at the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 31 Education during colonial times was tripartite: primary education (primeras letras) with the learning of the alphabet and elemental arithmetic; intermediate education (estudios menores) that included grammar, rhetoric, and Latin studies in the so-called colegios; and superior education (estudios mayores) at university level with the possibility of graduation. The Bourbon reform programme concentrated in particular on superior education. After the expulsion of the Jesuits – who had been deeply involved in the education system – in 1767, the Crown reconfigured the university system of the colleges and seminaries with new constitutions.Footnote 32 Unlike the primary education reforms, the vertically organised superior education system in colonial Peru remained an exclusive project primarily for the male elite in urban centres. In addition to sons of Spaniards and criollos, indigenous noble sons attended special schooling institutions in the two main cities, Lima and Cuzco.Footnote 33 For the booksellers, the highly educated graduates constituted a superior clientele, as they read – even in different languages – about diverse subjects and, in addition, had substantial financial means for buying books. Beside this sophisticated customer group of letrados,Footnote 34 other social strata of lower rank increasingly acquired the ability to read, and must not be left out as a possible audience and customer group when studying the colonial book market.

Inspired by the Enlightenment context, public education became a focus of government reform at the time. Against the background of the Bourbon reforms from the mid-eighteenth century on, new programmes spread primary school education into the different layers of society and beyond the capital. This progress in education entailed slow changes in what to date had been hierarchically organised education. In the city there were primary schools, like the Escuela de los Desamparados in Lima, created in 1666 for the ‘poor’ Indians of El Cercardo, where a century after its foundation roughly 300 children attended school for free, learning how to speak, read, and write in the Spanish language. Clergymen taught the alphabet in combination with Christian doctrine, and, in remoter areas, friars directed missionary schools. While education had been very much in the hands of the Church, at the end of the eighteenth century the civil government intervened progressively by conceding licences to lay teachers who met the conditions of good behaviour, pure faith, and ‘blood purity’ (limpieza de sangre).Footnote 35 Following an enlightened ideal of education, an article in the periodical El Investigador in 1813 called for free schooling to include poor children too for the ‘benefit of the enlightenment’.Footnote 36 Especially for children at a younger age, education should be designed to ‘form them into worthy members of society’, as another article on enhanced study plans claimed during the liberal time of the Cortes de Cádiz.Footnote 37

Contemporary theories on Enlightenment pedagogy promoted the idea of public education, in the hope that universal access to knowledge would foster virtue and morality as central points of society. Formulated in several theoretical treatises by Spanish intellectuals, such enlightened ideas of education could be found in the writings of Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, and Fray Benito Jerónimo Feijóo, among others, who endorsed reason and equality as principles of education.Footnote 38 Indeed, such texts circulated in Peru and shaped discourse on popular education, also forming part of the book collection of the Peruvian Viceroy Agustín de Jáuregui in 1784.Footnote 39 It was his predecessor, Viceroy Manuel de Amat, who, in the 1760s and 1770s, had already begun to restructure education in the viceroyalty, according to the reforms in Spain under Carlos III. Following the Enlightenment pedagogies of the time, children were to be educated in public schools to turn them into useful citizens and, specifically in the Spanish Empire, into good Christians.Footnote 40 Yet the ideas formulated in Spain were very different from the situation in the viceroyalty with its hierarchically organised society. Translating the ideas and programmes of Spanish education reformists who promoted literacy for all into the Spanish American setting implied education also for marginalised subaltern groups, as Cristina Soriano has studied for the case of free Blacks (pardos), who did not attend school in colonial Venezuela until individual projects tried to implement the Spanish reforms on site.Footnote 41 Against the backdrop of colonial society, the education of pupils, whether of children of ‘mixed’ ancestry (castas) or indigenous or poor, became a debated topic in Peru as well. Parallel to the Spanish reformists of Enlightenment pedagogies, but designed specifically for indigenous children, the Protector of Indians Miguel de Eyzaguirre laid out a programme of education in his Ideas acerca de la situación del Indio (1809), while the subdelegate of Huaraz Felipe Antonio Alvarado wrote about the situation of children in Huaylas in Breves Apuntes para la descripción del Partido de Huaraz (n.d.), referring also to the need for schooling.Footnote 42 Both writers put emphasis on the need for a good education, in particular for practical classes, to overcome the state of poverty in which many indigenous children lived, highlighting the benefits for the viceroyalty of having educated subjects.

Despite the enlightened idea of equality in education and corresponding programmes to spread schooling, geographical location and ethnicity still strongly determined access to education and literacy in late colonial Peru. The general scarcity of teachers as well as the lack of funds for salaries thwarted plans for spreading primary education, and rural communities in particular had difficulty in sustaining schools and paying teachers, as complaints about the situation prove.Footnote 43 Contrary to the situation in towns, illiteracy thus remained higher in rural communities where a majority of indigenous people lived. In the eyes of some Spanish authorities, indigenous people did not read or, in their words, ‘the Indians never buy books’, as stated in a discussion about the publication of Inca prints in 1796.Footnote 44 Such a bald statement reveals, above all, contemporary prejudices with respect to print culture and expresses views of ‘colonial difference’ which was based on the argument that the illiterate were intellectually inferior.Footnote 45 Allegedly not frequent book buyers, neither indigenous nor mestizo people were entirely absent from print culture. While hegemonic colonial categories tried to classify groups as ‘Indian’, ‘mestizo’, and so on, especially in the cities, which were great levellers, distinctions between individuals of different ethnical backgrounds gradually diluted to nuances.Footnote 46 Moreover, in some rural schools, if a competent teacher had been found, pupils were allowed to attend class together irrespective of their ethnic background, which was a result of austerity measures rather than of democratic educational endeavours.Footnote 47

From the very early times of colonisation, the Spanish Crown had demanded schooling for indigenous children and had put emphasis on printed cartillas as educational tools. Primary education for indigenous children went hand in hand with evangelisation and was based almost entirely on the Spanish language.Footnote 48 Some educated Indian leaders (caciques) were aware of the significance of literacy and promoted the learning of Spanish as well as writing skills so that indigenous pupils could participate in the ‘lettered city’. In petitions, they demanded admission to Andean schools, among which was also a project for self-run Indian schools.Footnote 49 In Peru as in New Spain, indigenous men and women requested the opening of schools exclusively for the native population, following notions of contemporary Enlightenment discourses and using them for their own pragmatic ends.Footnote 50 In line with the reform efforts of the time, the necessity of more basic education also became a topic at the Lima Provincial Church Council in 1772, with the recommendation for more primary schools in towns – reiterated by decree in 1800 which called for a school in every Indian village (pueblo de indios).Footnote 51 Yet educational ideology did not necessarily coincide with everyday reality, and individual projects filled the gap. For example, during the 1780s Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañon, Bishop of Trujillo, initiated an enlightened reform project with the erection of new schools, colleges for Indians, and primary schools in the town, some only for girls.Footnote 52 Female education was separate from the instruction of boys, as in the colegios for women that existed in Lima and Cuzco. In addition, convents and beaterios – places for women consecrated to a religious life in chastity – not only served for religious education, but also imparted elementary schooling to girls in larger cities such as Arequipa, Trujillo, and Huamanga.Footnote 53 In the various school projects, books did not necessarily play a prominent role, but teachers made use of printed material in class.Footnote 54

Reading could be learned at different places and on various occasions, not only in schools. Taking more than institutional forms into account, such kinds of ‘informal education’ further increased literacy, especially among the marginalised groups of society who did not attend class. As Gabriela Ramos has pointed out for indigenous people, it was likely that for many learning took place outside school and in a haphazard way.Footnote 55 In the eighteenth century, the structure, availability, and access to school-based education had improved compared with earlier times, but the concept of ‘informal education’ nevertheless still holds, offering a broader perspective of literacy acquisition beyond institutionalised terms. Through the family and the guilds, in convents or in the homes of private teachers, reading could be learned informally. Beyond the institutional framework, reading was handed on to the children if the parents were literate, as recollected by Catalina de Jesús Herrara from Guayaquil: ‘My mother kept me busy learning to read, with which I had no difficulty, because of my interest in knowing fables and history […] and they told me that one learned those things in books’.Footnote 56 In addition, individuals offered private classes, as in the case of an announcement in a periodical from 1790 by a ‘lady’ (señora) who taught boys and girls how to read in Lima.Footnote 57 Convents and notaries’ offices, along with private spaces, built centres of learning for young Indians and mestizos who did not attend school but received education at these places.Footnote 58 On an informal level, literacy was driven forward by religion, commerce, and legal demands.

The children of castas – mestizos, zambos, mulatos, and cuarterones – were not allowed at the colegios and the university, where ‘blood purity’ was one of the requirements, and they rarely attended primary school either. In this sense, education has been described as ‘social discrimination’ as well as a ‘privilege of class’ that oscillated between the retention of social hierarchies in colonialism and the integration of dominated groups into colonial society.Footnote 59 Instead, such children acquired the skills they needed for their occupations as tailors, carpenters, or barbers through alternative educational means provided by the guilds of craftsmen or the master.Footnote 60 Slaves, with the exception of unique cases, did not have access to formal education.Footnote 61 While the educational system was not designed to include them, single cases stand out where they participated in the lettered sphere, whether at court or in print culture. Scholarship has emphasised their agency, as in the case of Manuela, a zamba slave in Lima, who in the 1780s went to Court to litigate against separation from her husband and signed the petition herself.Footnote 62 Notable in this sense is also the impressive book collection of Juan José Balcázar, a freed slave (cuarterón libre) who at the beginning of the century had over 194 titles.Footnote 63 Individual undertakings further served to break down social barriers, as was the case with the periodical Diario de Lima, published from 1790 to 1793 by Jaime Bausate y Mesa, who claimed that his periodical addressed slaves and pupils, boys and girls, and taught them how to read.Footnote 64 Although the vast majority of slaves and free people of castas were excluded from formal education and did not read themselves, they were familiar with the written word, at least in the cities.

Both writing and reading could be delegated and transferred. Literacy in this respect is understood less as a taught and learned skill, acquired or not, than as a set of cultural practices. Despite their subaltern position in colonial society, individuals in Peru partook in the lettered sphere on a regular basis by delegating their writing, for example to professional notaries.Footnote 65 Public writing thus formed part of cities’ open spaces, where anybody could encounter it. Even for the many who did not receive any form of alphabetic education, various modes of reception and popular practices enabled access to the written word in daily business. Consequently, the simple calculus of one book corresponding to one reader does not hold. Especially in the case of a past society and one as fragmented as in the Viceroyalty of Peru, the apprehension of texts could change between loud and visual, intensive and extensive, as well as solitary and collective reading, with all its nuances and gradations, as the discussion of reading practices in Chapter 5 will show. Therefore, contact with the written word did not imply holding text on paper in one’s hand, or necessarily possessing a book, as print pervaded colonial society in many ways, especially in the urban areas, to a growing degree. Although illiteracy constituted a restriction on the market for books, the increasing quantity of print publications reached an unprecedented number of persons both literate and illiterate.

1.2 Legal Barriers

During the period of Spanish colonial rule, a framework of licences and privileges regulated printing, while a dual control mechanism served to oversee trading at the various sites of the Empire. As stipulated in the laws enacted in the metropole in Castile, the regulations were a product of the interplay of political and religious influences and curtailed a free unfolding of print culture. Major concerns in Spain about the dissemination of unorthodox ideas after the Protestant Reformation in Europe, together with commercial intentions aimed primarily at protecting the business on the peninsula, led to a set of restrictions that, between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, had grown into a body of legislation comprising over seventy laws.Footnote 66 Regulations concerned virtually every aspect of the market, treating the printing of books and the trade in them as one subject. This judicial apparatus was extended to and to a certain degree tightened in the viceroyalties to guarantee surveillance, as compiled in the Recopilación de las Leyes de Indias.Footnote 67 Being reinforced by royal decree on occasion, the compilation maintained its validity until the end of the viceroyalty, interrupted only by the different regulations during the Cortes de Cádiz.Footnote 68 While the laws on printing and trading books for Peru were no different from those in Castile, the legislation for the viceroyalty was amended with further prescriptions over time. José Toribio Medina has spoken in this respect of a ‘multitude of obstacles’ in the Spanish colonies,Footnote 69 but little is known about the implications and effects that laws and control measures had for the development of the colonial book market.

In the capital of Lima, where licences, privileges, and prohibitions of the trade launched debates, the printing of primers developed into a fiercely contested matter, with many parties competing to take advantage of the revenues of the book market. Questions of colonial conjunctures and legal sanctions on book circulation in Peru can be illustrated by the relatively well-documented example of the cartillas. The king’s concession of printing privilege to the workshop of the Orphanage in Lima, called Imprenta de los Huérfanos or Casa de los Niños Expósitos, first in 1619 and repeated in 1733, was an act of beneficence that had profound effects on the printing trade in the capital.Footnote 70 In line with the philanthropic spirit of the Enlightenment, the care of orphans and foundlings continued to form part of eighteenth-century royal charity work, helping to fight social problems in the colonial city. This constituted a necessary task, as the strictly hierarchical casta system excluded many people, and religious and moral beliefs caused the abandonment of illegitimate children in front of church portals. Bourbon social policies included the orphans as young imperial subjects and therefore the Orphanage received the privilege of the primer trade, in turn providing Christian education for the increasing number of orphans.Footnote 71 As in Lima, printing as a source of income for charity institutions was the case in other parts of Spanish America too, as in New Spain, where the Hospital Real de Indios in Mexico had held the privilege of trading primers since 1553, and extended also to newer printing sites such as Buenos Aires in 1781, where the Orphanage’s workshop equally produced thousands of primers.Footnote 72 As a much-required genre used to learn the alphabet, cartillas represented one of the most popular publications for the colonial workshops.

Equipped with the king’s exclusive monopoly on producing these bestsellers, the press of the Orphanage in Lima became the leading printing workshop. While at the beginning the Orphanage had rented out the privilege to individual printers, production took place in the newly established workshop in the same building from 1748 on, and the administrators insisted on safeguarding the ‘pious decree’.Footnote 73 Against contraventions of the printing privilege, the Orphanage in Lima had to renew its royal decree several times. In 1758, the administrator discerned that although other printers in the city might have the types, the press, and even the skills to print the primers, they did not have the right to print them.Footnote 74 Every now and then, the administrators therefore urged a proclamation (bando) of the single printing privilege.Footnote 75 Irrespective of the privilege, other printers tried to take advantage as well by producing the bestselling cartillas, and the illegal trade in primers flourished.Footnote 76 Through extended litigation in the archival files, it becomes clear how, for generations, printers and traders contested the privilege. In the market, the making and trading of primers had developed into a highly competitive business. Guaranteed to a single institution, such exclusive printing rights formed part of the comprehensive colonial jurisdiction, fostering the development of certain workshops, but to the detriment of a free and competitive development of the printing trade.

In addition to the printing monopoly, the regulations on imports hampered the business. Books from Spain satisfied large parts of the demand in Peru, favouring Spanish printers and traders as well as the Crown, which collected taxes on the book trade.Footnote 77 Commercial interests competed for the revenues of the book trade and rights had to be defended and renewed. The case of the profitable cartillas illustrates this again: from the very early times of colonisation, primers were sent in big quantities to Spanish America regardless of the early printing privileges for American institutions. In the eighteenth century, the Cathedral of Valladolid in Spain as a production centre of primers fought for the extension of its privilege in view of the big sales market overseas. To the benefit of American print production, the Council of the Indies rejected the request of the cathedral in 1780.Footnote 78 Yet, despite this protective right, imported cartillas continued to concern the administrators of the Orphanage in Lima, which complained about the large quantities that arrived from Cádiz at the harbour in Callao, asking for their confiscation directly at the custom house.Footnote 79 For most of the time, the total number of cartillas that entered via import was unknown, yet the ongoing concerns of privilege holders provide evidence for how big the – illegal – commerce must have been. In the words of the administrator Don Juan José Cavero, who had to insist on the Orphanage’s privilege several times, the uncontrollable book trade was ‘contraband commerce’.Footnote 80 From his point of view, both the imported cartillas and those from other printing workshops in Lima curtailed the value of the privilege, severely hampering the business.

It was a general phenomenon of the colonial book market that local printing and imports supplied the market. Thus, primers from two sources, the Limeño workshops and Spain, satisfied the demand in Peru. Once a book was printed and on the market, users probably did not even discern the different origins of a book. In 1814, the merchant Don Francisco Iglesias Franco, who traded regularly in imported wares, had one and a half boxes of first readers (catones) printed in Lima in his shop.Footnote 81 In addition, stall sellers (cajoneros) in Lima and pedlars who left the city (comerciantes transeúntes) sold the cartillas – according to complaints often illegally without a licence – in and beyond the capital.Footnote 82 Through the harbour of Callao, the booklets went across the entire viceroyalty, to Chile and the intermediate ports.Footnote 83 The case of the trade in primers serves to illustrate the colonial book market as a whole, as it shows, first, the composite structure of the Peruvian market, fed by Limeño production and imports; second, the legal barriers and the different rules regarding the trade in the viceroyalty; and, third, the continuous violation of regulations due to ignorance or profit motives. Against these and other sorts of contraventions, an intricate system of surveillance confined the free circulation of books in colonial Peru from the outset.

For imports, the harbours on both sides of the sea functioned as control points, meticulously registering the movement of books. Since 1717, practically all the books that were sent across the sea to the different Spanish realms departed from Cádiz, where in a process of laborious work around the House of Trade (Casa de la Contratación) the transshipment took place. As the principal Spanish port for the transatlantic trade, Cádiz was a bottleneck, with its bustling activity of tradespeople. The population in the harbour city increased to 77,500 inhabitants in 1790, even more than the Peruvian capital Lima, which only after the turn of the century would achieve a comparable number of inhabitants. Cádiz itself offered an active print culture with more than fifty people working as printers or booksellers at the end of the century.Footnote 84 Every book that began its journey destined for Spanish America had to pass the port’s control institutions; altogether, the loaders had to accomplish inspections in the warehouses, customs clearances, the treasury as well as the House of Trade, and, of special importance when sending books, the Holy Tribunal of the Inquisition.Footnote 85 A book thus had to pass through many steps and travel on various routes before someone on the other shore could hold it in his or her hands and leaf through the pages of the object that had come from such a distant place as Europe.

Despite the reforms and the opening-up through free trade regulations in the second half of the eighteenth century, the major ports still dominated. Their position, however, was no longer unique and protected by monopoly. After the successive introduction of free trade (libre comercio) in 1765 and especially in 1778, new harbours opened to the transoceanic trade.Footnote 86 Now books could also be shipped via minor ports. For instance, from Santander, one of the new Spanish harbours participating in the transoceanic trade, ten boxes of books were sent in 1803 to Callao by the merchant Don Antonio Pérez de Cortiguera, father of one of the leading book trading merchants in Lima.Footnote 87 Despite the opening of new ports, still more than 70 per cent of exports departed from Cádiz, and Callao maintained its position as the most important harbour in the Pacific, receiving more than 20 per cent of export goods from Spain. Through its central location on the Pacific coast of the southern continent, Callao remained crucial.Footnote 88 Closely connected, the Peruvian capital Lima, located six miles to the interior, constituted a big warehouse and platform for the distribution of resources and products disembarked at the port. Among the commercial consignments, book imports arrived that were destined for the capital and for the whole region.

The overland trade routes, by contrast, from New Spain to the South or the Río de la Plata region to the West, seem to have been a less frequent option for books. These were used especially for private consignments, such as by the friar from Quito who on a long pilgrimage brought 116 boxes with books from Cádiz via Buenos Aires to his monastery, selling off parts of the load along the way to be able to pay his travel debts.Footnote 89 Places in Upper Peru that before had been connected to Callao as the single storage and distribution centre now also received their products via Buenos Aires, capital of the new viceroyalty since 1776, where imported products could be bought at cheaper prices due to the reduced distance and safer route from Spain. Potosí, for example, established a connection to Buenos Aires via a direct route between the mountains and the Atlantic without the detour via Callao. Not only metals and correspondence but also books moved through the overland route, as proven by a large consignment of 317 different titles. The overland route, however, also took some time, almost a year from departure from La Plata on 22 August 1776, until arrival in Potosí on 13 August 1777.Footnote 90 Though Callao’s primary role was contested through the profound trade reforms and the opening of more ports for transoceanic commerce, the harbour continued to be one of the most important for the reception of book cargoes.

As with other goods, books had to pass customs and traders had to pay taxes at the harbour. It remains unclear whether these customs duties hampered the increase in the volume of books traded between Spain and Peru because commercial legislation brought several changes, which were not always implemented or complied with. Taxes were charged per cargo box and, from 1765, duty was levied on the value. For a box of books merchants had to pay far more taxes than on other items: 5 pesos on Spanish print publications and 20 pesos for those of foreign origin – meaning not of Spanish production – compared with, for example, a box of drugs, which was charged at 1 peso. In the course of the implementation of free trade as part of the Bourbon reforms, the duty calculated on the pack size (derecho de palmeo) was substantially reformed into a duty on the worth of the goods (ad valorem), although still clearly favouring products from Spanish presses in comparison with those of foreign origin: goods from Spain paid 3 per cent, while those of foreign origin paid 7 per cent on their shipment to Spanish America.Footnote 91 Large consignments of titles arrived at Callao, where they passed the controls before being redistributed.

The changing legislation on imports and the different related regulations created over the course of time required interpretation and explicit declarations by users in harbours and at customs. In 1788, for instance, the new legislation had raised doubts concerning the distinct treatment of books by origin, from either Spanish or foreign workshops. In addition, the purpose of the trade created discrepancies due to the tax system on imported goods and on resale, while private persons were exempt from taxes.Footnote 92 It was stipulated that books that were introduced by merchants for trade into the viceroyalty had to pay fees, while books for private possession – called in the regulations for ‘lettered persons’ (literatos) – were free of charges.Footnote 93 Due to repeated disagreements, ‘major uncertainty’, and the generally ‘dark and complicated jurisprudence’, the decrees were reiterated in 1791 and sent from Lima to Huancavelica with pertinent explanations.Footnote 94 When two Spanish merchants imported eighteen boxes of books, they first had to present a list of titles to the Holy Tribunal, then, on the same afternoon, they went to customs for the receipt of the books where, in a second step, they received a pass to extract the boxes. However, they refused to pay the duties in Callao and a debate arose about the legitimacy of the claim.Footnote 95 To transport books implied the necessity of obeying the commercial regulations on both shores, and, if worst came to worst, paying fees twice. Despite such uncertainties, the taxes, the long trade routes, and the many administrative steps, books were a frequent cargo on the ships that sailed to the viceroyalty.

For most of the colonial period, a dual mechanism of censorship – before as well as after publication – controlled all print publications, including books, on the market. Split into preventive and punitive censorship, this system made the legal situation of books in Spain and the viceroyalties unique. Prior to publication there was the censorship of the Royal Print Court (Juzgado de Imprenta), which through the king and viceroys granted licences to print with the support of the Council of Castile and the Council of the Indies; and after publication the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition exerted censorship on printed books to guarantee orthodox content.Footnote 96 While a privilege was an exclusive right for the printing of a specific genre, as in the case of the primers, printing licences became obligatory for all sorts of texts, even for the university after a scandal in 1781.Footnote 97 Once a book was on the market, it remained under the surveillance of the Inquisition, established in Lima in 1570, which effectively controlled many aspects of social life. Like the Inquisition’s responsibilities in Spain but proceeding and censoring books on its own initiative, the Tribunal in Lima acted against heresy to promote the pure faith and the unanimity of religion in the viceroyalty. As part of its duty, all books that met one of the following criteria had to be banned: those that were contrary to the Catholic faith, themes that fostered superstition or were considered obscene, attacks against honour, and, lastly, publications without a printing licence or reference to the author, printer, place, and year of printing. For this purpose, the Tribunal in Lima acquired broad judicial authority, financial resources, and a bureaucratic system.Footnote 98

Books, in contrast to other shipped merchandise, required two additional documents in Spain: a record of the book title as well as a licence from the Inquisition to transport them. The commissioner of the Inquisition therefore issued a list of all the book titles in every box on the ship for the consigner – be it a merchant or a private person – to show that the books had been reviewed and did ‘belong to the common ones and not to the prohibited’.Footnote 99 Individuals, especially those who often dealt with clandestine shipments, knew well how to circumvent the controls, and did so. When in 1780 Manuel Salas, a young Chilean who studied law in Lima, was loading five boxes of books that he had bought in Madrid for the transatlantic journey, numerous prohibited books were discovered in his shipment that he was not allowed to carry with him.Footnote 100 Infringements like this continued over time. More than thirty years later, after having arrived at Callao, the lawyer Juan Freyre presented a list of titles he had imported for his private use, yet the register list included suspicious titles that had been removed from his three boxes, and he got into trouble.Footnote 101 Prohibited titles that came to Peru formed part of the private luggage of, in the majority, professional, male travellers, who often knew exactly which titles could cause inconvenience and also how to bypass the controls.

To control the circulation of books, the Inquisition relied on two methods: the list of prohibited titles (Index librorum prohibitorum) and visitations (visitas). While there is much scholarship on the Inquisition, little is known about its confining effects on the book market through usage of the Index or the inspections.Footnote 102 First, catalogues, called the Index, listed all the prohibited titles of heretical texts and those considered to be theologically dangerous.Footnote 103 Most booksellers must have conducted their daily work by carefully avoiding having such dangerous titles in stock. Probably for this purpose, in 1801 the merchant Don Josef Arrizabalaga had a copy of the Index of prohibited titles in his shop in Lima.Footnote 104 The fact that the Index figured in the inventory of his stock shows, at the least, his acquaintance with the catalogue, which also served for the Inquisition’s visitations of shops. Second, the inspection (visitas) of ships, bookshops, and individual collections served as another enforcement branch of the Inquisition and involved calling in experts on demand, mostly ecclesiastical scholars.Footnote 105 Printers in Lima could not publish what they expected would find a ready market and booksellers were not allowed to supply and offer what they thought would boost their sales, as – in theory – the whole trade was tightly regulated by restrictive laws, licences, regulations, and prohibitions.

Through the course of the eighteenth century, the control of the book trade became more severe. The intervention of the Council in Spain grew considerably from 1760 onwards with a much higher denial of licences compared with the first half of the century.Footnote 106 Although the power of the Inquisition gradually decreased, of the 2,000 titles in the Index 90 per cent were published between 1740 and 1820.Footnote 107 This change also manifested in the different attitudes to the superiority of the viceroyalty: while in 1767, the Viceroy Manuel de Amat himself counted prohibited titles within his possession and showed reluctance to cede them to the Inquisition, in 1780 his later successor Viceroy Teodoro de Croix implemented new orders regarding the control of books, with a special preoccupation with the category of prohibited titles.Footnote 108 In times of upheaval, proclamations of prohibited titles increased, for instance after the rebellions in the Andes during the 1780s or events across the globe, such as the American declaration of Independence in British America and the turmoil of the French Revolution in Europe.Footnote 109

The book by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega presents a case study for attempts to exercise control over the late colonial book market. Born in the years of the conquest, the Peruvian chronicler and mestizo author explained, in his authoritative history, pre-Hispanic customs, traditions, and the Spanish overthrow of the Incas; the book was widely read in Europe as in eighteenth-century Peru. Amid the uprisings in the Andes, however, and especially after that by Túpac Amaru II of 1781, Spanish colonial authorities related the increasing ‘nationalist movement’ that aimed to restore the Inca dynasty to the knowledge of pre-conquest traditions which circulated in print publications. In 1782, and again in 1795, a royal decree interdicted the trade and possession of the Comentarios reales by Inca Garcilaso, ‘in which the naturals have learnt many harmful things’.Footnote 110 Different editions of the book had made their way to Peru since its first publication in 1609 and the second volume in 1617, and, especially after a new publication in Madrid in 1723, the distribution of the book further increased.Footnote 111 In the eighteenth century, the indigenous elite spoke the Spanish language, had easy access to the printing press, and orally conveyed the message of the book, as scholars of Andean conspiracies have pointed out.Footnote 112 To fight colonial abuses, the Inca nationalist movement took its prophecies from this textual source, in particular from the prologue to the 1723 edition by Andrés González de Barcia Carballido y Zuñiga, according to the interpretation by John Rowe.Footnote 113 In fact, the book was owned by the rebellious indigenous leader Túpac Amaru II, as his bill of custom proves.Footnote 114 Despite the royal decree against the work of Inca Garcilaso after the uprising, which included the command to impound the book, it figured frequently in collections throughout the viceroyalty.Footnote 115 In fact, all the regulations and restrictions could not prevent the circulation of books; they rather give evidence of their existence and continuing circulation.

Although contraventions did exist, no general measures were adopted to reform the control mechanisms, only single decrees. In practice, the colonial system of book control seemed to have worked to some degree in Spanish America. It is, however, very doubtful that printers and booksellers were always well informed about the complex legal situation. Often, not knowing the exact regulations, they acted in accordance with their predecessors and colleagues, as a consequence provoking the authorities to remind them of the laws and restrictions through edicts.Footnote 116 Nevertheless, such proclamations did not necessarily reach everybody engaged in the trade. According to his defence, the salesman Bartolomé Ponze de León had been in Lima on the day of the edict, 11 November 1778, but he did not receive the news about the prohibition on the trade of illegally printed primers.Footnote 117 In contrast, other laws seemed to have lost their validity over time. Although never repealed, the legislation on prohibiting the import of fabulous and fictive stories (libros fabulosos) to the viceroyalties was not enforced, neither in the sixteenth nor in the eighteenth century.Footnote 118 As in other cases, legislation was one aspect, daily practice another. For two and a half centuries, the system of book control remained essentially the same in the whole Spanish Empire. The only substantial exception was the changing regulations on the Freedom of Print and Expression by the Cortes de Cádiz, a short interregnum that lasted from 1810 to 1814.Footnote 119 And even after 1814, the Inquisition was immediately re-established in Lima to continue in its regulatory force, publishing several edicts,Footnote 120 indicating a renewed preoccupation with the issue of book circulation and control. The continuous concern and strict surveillance on the part of the Spanish Crown and the Inquisition still in place in the late eighteenth century and the first decade of the nineteenth point to the economic and ideological significance of the book trade in the viceroyalty.

Surveillance of the publishing industry was a general phenomenon of the time, shared by various European monarchies. Whereas during the age of manuscripts the Church had acted as the main institution controlling the distribution of texts, in times of printing its influence over the market gradually decreased. In most places, ecclesiastical print control receded during the course of the eighteenth century as the state assumed the role of supervising the publishing business.Footnote 121 A secularisation of censorship could be found in various places: from lay control over the book business in Russia to the power of the Royal Board of Censorship in Portugal, from the state’s direction of the book trade in France, where privileges and pre-publication censorship collapsed after 1789, to a guild’s regulatory force in England with the Stationers’ Company for printers and booksellers.Footnote 122 When comparing censorship regulations in Spanish America with the legal conditions for publication in the British colonies, the latter have been judged as more favourable.Footnote 123 While often the state and publishing were neatly intertwined, in the Spanish Empire it was the state authorities in conjunction with the Inquisition that still controlled book production as well as the transoceanic trade.

Extensive legislation thus curbed the colonial book trade through the dual control of preventive, through licences and privileges, and punitive censorship by the Inquisition via the Index and visitations. The main reasons driving the strict control of the book market lay in the control of the circulation of ideas, the possibility of revenues, and the protection of typographical establishments. To continue circulation without statutory hindrances put in their way, the printers and traders in Peru had to adapt to this legal framework, which in many cases treated Limeño production together with imports as one subject. There were, however, further obstacles that hampered production in the workshops in colonial Lima.

1.3 Material Difficulties

As well as legal restrictions, printers also encountered material difficulties, working under conditions of constant shortage. The colonial context created a particular framework of scarcity and hardship for the craft of printing in Peru. The supply of necessary materials for the manufacturing of books was subject to colonial market relations, with various regulations limiting access to equipment that had to be brought from Spain and was thus scarce. In contrast to the legal situation of the book trade, the material conditions of printing remain largely unexamined.Footnote 124 The making of a book required many intermediate goods: paper of a certain quality, thick fat-based ink, and bookbinding materials to stitch and cover the sheets. In addition to various capital goods such as the printing press, there were metal types in the form of letters and text symbols as well as a case to organise these, along with composing sticks, metal galleys, wooden chases, and balls to distribute the ink. For the majority of these items, the printers in Lima depended on imports. By focusing on the origin and supply of different components of the craft, the limited material conditions for the craft of printing become apparent.

Paper, the foremost manufacturing material for printing, always came from Spain and was therefore a valuable commodity. Its significance is illustrated by the following story published in the periodical El Investigador about a case of theft in Lima in 1814. From the Convento de Descalzos, not money but books had been stolen – and not for the first time. During mid-afternoon, an armed burglar had broken through a cell window to steal a friar’s books. The book thief, described as of mixed African and Indian ancestry and slit eyed (zambo achinado), wearing a poncho and armed with a dagger, escaped immediately. The thief took the books to the market stalls by the river – the Cajones de Ribera – where the pages of such stolen books were used to wrap ingredients and other harvested goods.Footnote 125 This anecdote first illustrates the recycling of book sheets in times of high paper prices, and second uncovers the depreciating value of books with the loss of content for the reuse of their material. One of the trafficking locations, the Cajones de Ribera, formed a bustling marketplace where, among other goods, books were sold. The writer of the article, however, does not indicate the reselling of the stolen books but, on the contrary, their destruction and material reuse – a significant part of the ‘cultural biography’ of a thing. With the material determining the object’s lifespan, the itinerary of the stolen books continued to a different destination. Even more drastic is the fact that the stolen books were religious, described as ‘peculiar books and of monastic subject’,Footnote 126 yet, despite this, they were used as simple wrapping paper for groceries.

Throughout colonial times, the Crown held a monopoly of paper production, which was fabricated exclusively on the Spanish peninsula or in Europe, but not in the viceroyalties. A jealously guarded resource, paper built the base for the whole colonial administration, with ‘pen, ink and paper’ as symbols of the colonial system of the Spanish Empire ruling across the Atlantic.Footnote 127 Early attempts to establish paper mills in Spanish America did not succeed, as either no licence was given to make paper in the viceroyalty or enterprises failed.Footnote 128 According to its cargo list, drawn up in Cádiz at the end of 1787 and with the destination of the Peruvian port Callao, the frigate El Paxaro had loaded 4,118 reams of paper and 172 pieces of painted paper (papel pintado) from Catalonia together with 20 reams of golden paper (papel dorado) and 16 reams of white paper from abroad. Contemporaneously, the bigger frigate La Rosa carried 119 pieces of painted paper from Seville, 304 sheets of paper with black margin (láminas de papel con marcos negros), and 85 prints on paper (estampas) from Cádiz, 1,000 reams of kraft paper (papel de estraza) from Granada, and 260 reams of paper from Catalonia.Footnote 129 Paper built the material foundation of correspondences, bills, contracts, powers, receipts, wrapping paper, and was the basis for paintings and the printing of cards and invitations, as well as of books. The trade included a variety of sorts: ordinary paper (papel común, papel de Valencia), blue paper against insects (papel azul), quality paper (papel superior de Cataluña, papel florete), and taxed stamped paper (papel sellado) used for all legal and administrative affairs.Footnote 130 For printing, quality paper – called regular ó comun – with the mark from Catalonia had to be used, in particular the same paper for one book, paying attention to good cutting and aligned edges.Footnote 131 Several orders exemplify this preoccupation with quality, and visitations of workshops surveyed the utilisation of excellent paper (papel fino), as shown by a royal decree in 1751 for the production of cartillas. This minimum standard of quality paper applied to all sorts of printing.Footnote 132

In Europe, the two industries of papermaking and book printing became closely interrelated.Footnote 133 By contrast, Spanish America received paper in high quantities from Spain and did not produce any paper of its own, following a colonial restriction. Even rags collected in Peru had to be sent back to Spain as basic material for papermaking there.Footnote 134 Yet Spain lagged behind in paper production and now and then, when quality paper was scarce, printing continued with ordinary paper.Footnote 135 To foster the manufacture of paper, in 1778 the Crown’s economic ministry ordered the translation into Spanish of a treaty on papermaking by the French author Jérôme Lalande.Footnote 136 With only a few mills, mostly in Valencia and Barcelona, there was not enough paper to satisfy the demand even on the peninsula. Thus, Spanish merchants acquired supplies from producers in Genoa as well as several French and Dutch centres of paper production and sent them to Spanish America. Packed in cloth as bales (balones), the paper was loaded at the harbour of Cádiz or La Coruña to cross the Atlantic.Footnote 137 Paper imported to Spanish America amounted to up to 5.4 per cent of merchant ship freight. The demand grew constantly, as evidenced by calculations for the second half of the eighteenth century in comparison to the first half, which show that the volume of paper imports tripled to a total of 7.5 million Spanish reams.Footnote 138

Due to the dependence on import, the value of paper in Spanish America was consistently high, further increasing in the long run. From New Spain to Peru to Chile, the situation with imported paper was comparable. By the end of the eighteenth century, the price in Mexico had risen from 3 to 9 pesos a ream. This increase led to reutilisation practices like wrapping groceries with obsolete seventeenth-century stamped paper, which was actually for notarial deeds, resembling the story of the book thief in Lima. In other cases, due to the lack of paper printers overprinted the official paper with the stamp of the current year.Footnote 139 During the crisis of paper in 1805, the Mexican Viceroy even ordered a reduction in format and type size for colonial institutions to economise on this valuable material. Due to its scarcity, printing was intermittently suspended and the production of books diminished, while some workshops had to close.Footnote 140 The price of paper rose in Lima, as in New Spain, though less dramatically, while the living cost remained more constant. Whereas paper prices had varied significantly at the beginning of the eighteenth century, in the second half they stabilised at approximately 5 pesos a ream, fluctuating between 3 and 6 pesos. Lima, with the nearby port of Callao, had better access to the material, while in other cities of the viceroyalty the price of paper could be doubled: in the 1770s a ream of paper in Lima was approximately 4 pesos in contrast to Potosí where its price was almost 8 pesos. Around 1800, however, prices went up to a remarkable peak of more than 10 pesos per ream in Lima.Footnote 141 Of course, such high paper prices directly affected the craft of printing.

Paper, as a relatively expensive component, determined the price of the end product. As an intermediate commodity of the printing process and consumed in large quantities, it could have a substantial impact on the price of a colonial book. For printing jobs in early colonial Peru, it was common for authors to have to provide paper for the printing of their manuscripts, and in these cases the printers had to return surplus and scrapped paper to the client.Footnote 142 Only a few billing records for printing in the late colonial period have survived in the archives, and most of them are post-production bills rather than pre-production contracts. The very detailed account for the publication of the prestigious Relación de las reales exequias of 1768 reveals a rate of printing of 10 pesos per sheet and the high prices for engraving (49 per cent) and bookbinding (24 per cent), while paper – at the time 4 pesos per ream – was 8 per cent of the total sum for the 400 copies.Footnote 143 In 1785, Augustín Ramos printed 180 small calendars in Lima for the Church in La Paz. The expenses of this project encompassed a range of items as the detailed account shows: the printing of the 180 cuadernillos billed at 10 pesos per sheet amounted to 57 pesos 4 reales, the paper used in two qualities combined was 8 pesos, the binding was valued at 3 pesos 6 reales, and, finally, the licence to print was an extra 10 pesos. Of the total cost of 80 pesos, paper made up 10 per cent and printing 71 per cent of the product’s end price, but only if not taking the high transportation cost to La Paz into consideration, which additionally increased the price by 30 pesos.Footnote 144 At that time the paper price was quite moderate, at around 3 pesos a ream. Only a few years later, in 1793, the printer Guillermo del Río produced passports, certificates, and licences, 500 of each, for the public administration. The price amounted to approximately 150 pesos, with the paper costs of 40 pesos making up 25 per cent of the total, a much higher cost than in the first example, as a ream of paper had risen to 12 pesos.Footnote 145 Therefore, as shown in these examples from Lima, paper as at times an expensive base material affected the production costs significantly, in some cases up to a quarter.Footnote 146 The colonial context of printing influenced the process, as paper was in general a product of imports, a relatively costly component, and not always abundantly available.

In another bill from 1803 between the same contract partners, the printing of 1,000 catones cost 100 pesos, plus 10 pesos extra for an inkpot (olla de tinta).Footnote 147 While paper had to be imported, printers prepared the ink in their workshops and used local leather and parchment for binding. These intermediate goods generated some additional costs in the process of printing and bookbinding, but were less expensive than the paper as they could be mixed on site or bought on site. As in Lima, printers in Philadelphia in North America acquired ink from local manufacturers or bought imported ink from England.Footnote 148 Spanish American ink production most probably followed the recipes for ink known at the time. In a detailed study, Marina Garone has traced a Mexican manuscript on the printing art, El Arte de ymprenta (1819), translated from a French dictionary, Dictionnaire raisonné universel des arts et métiers by Abbé Jauber from 1773, which also contains a description of ink and varnish production. Traditionally, the oil-based printing ink was made by cooking linseed or nut oil, adding resins like sandarac and turpentine to increase the viscosity of the varnish.Footnote 149 For this cooking procedure, inventories of printing workshops in Lima listed utensils, such as the already mentioned inkpot or, in another case, ‘a copper kettle in which the ink is made’.Footnote 150

Material restrictions were overcome by the invention of new methods for the manufacturing process and the employment of Peruvian natural ingredients. The topic of ink and typographic varnishes in Spanish America remains largely unstudied, but reveals more about the attempt to substitute for imports via the use of local materials instead. In 1791, an industrial announcement in the periodical Mercurio Peruano, which regularly promoted enlightened ideas for the progress of Peru, reported the invention of the engraver Don Joseph Vázquez to replace Chinese ink, which was used commonly for drawing but had to be imported from Asia. Samples proved that the ink was no different from the best one from China and prospecters, hoping to overcome the effort and expense of supply, announced the usefulness and considerable benefits of the discovery for Peru and for Europe. For all interested clients, the engraver provided the ink at his home in Lima.Footnote 151 In this case, ink production was based on the discovery of the ‘secret’ of the ink, without further disclosing the substances involved. By contrast, a manuscript recipe of three methods to cook ink reveals the use of native botanical products, such as Peruvian mint (yerba buena) and the bark of the native Peruvian tree called tara. For the making of ink, one had to take some Peruvian mint, together with pomegranate peel and half a pound of tara, cook these in six pounds of water until it was reduced by half, filter it, mix it with vitriol, and store it for use.Footnote 152 Yet such archival evidence is rare and, besides the announcement in the Mercurio Peruano and this handwritten eighteenth-century ink recipe, sources about workshops do not expose more about the preparation of printing ink in Lima.

As for the production of ink, printers and binders employed local materials for the book-binding process (encuadernación). They covered print publications with book cloth if they were not to be sold simply folded and stitched, as was the case for many cheap and short-run printing products. Binding served primarily to protect and preserve the printed sheets, but also affected the appearance. Whether a book had a simple trade binding or a luxury cover reveals much about its use, traditions, and possessors, as well as its status as an art object.Footnote 153 The material of the binding offered another feature of classification to distinguish sets of books. Two materials were frequently used for binding, a simple version called en pasta or a la rústica and a more elaborate one in vellum, called en pergamino, made traditionally with parchment of calf, sheep, or goat skin. The quality of the craft varied, and the Spanish Crown explicitly requested items with ‘good binding […] in Morocco leather’ for the return consignment of copies of the Guía de forasteros, the yearly guides published in the capital Lima.Footnote 154 The outer appearance was emphasised when the highest-quality fabrics like velvet and silk with impressed designs decorated the cover and book boards, following the trends of the European capitals Paris and London.Footnote 155 However, such costly materials as a blue velvet binding were reserved for exquisite publications.

Again, apart from contemporary binding as a physical object that tells us about materials and techniques – if the book was not rebound, as happened frequently in the late nineteenth century – only a few written references to this craft exist. Binding figured only occasionally as a distinct asset in the itemisation of printing costs or as a separate bill, revealing some information about the profession. For a printed object for daily use, binding must often have been carried out directly in the printing workshop, as in the case of calendars when it made up less than 5 per cent of the total cost.Footnote 156 Printers as well as booksellers engaged in the business, as shown in early printing contracts that included stipulations on binding from the beginning of the seventeenth century on.Footnote 157 In other cases a trained person was employed for the task of binding, such as the slave who worked in the bookshop of Salvador López the century before.Footnote 158 Over time, the occupation of bookbinding apparently developed into an increasingly independent job from printing. Binding was not always connected to a printing workshop, as was true for Francisco Bejarano de Loayza, who identified himself as a bookseller (librero) with a stock of 2,000 books on all subjects. In 1725 he had done the binding for various books, billed at 20 pesos, for the polymath Don Pedro de Peralta y Barnuevo, rector of the University of San Marcos, famous for his enlightened discourses and writings about the city of Lima.Footnote 159 For luxury books, a professional bookseller took on the task, as was the case when Juan Nabas bound the Relación de reales exequias in 1768. This expensive job cost 291 pesos, using blue velvet cloth (terciopelo azul) and silver clasps for three luxury copies, and white paper and – apparently Peruvian – parchment for the rest.Footnote 160 As in those two cases, a specialised bookseller or bookbinder embraced the practice, yet there is little information about such a profession in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

For binding the products of Lima presses only, bookbinding in colonial Peru did not develop as a sophisticated craft. In general, imported books arrived ready bound on the colonial market even though binding implied more weight, especially in the early times of wooden boards and metal clasps. In Europe, by contrast, it was common practice to send unbound book sheets in barrels from one town to another to prevent increased transportation costs, and buyers could decide independently on their binding style and expense.Footnote 161 In order to protect the domestic binding craft in Spain and allow for its development, books from neighbouring European countries were to be imported without binding. Different prohibitions between 1778 and 1802 addressed this issue, ensuring extra income for the Spanish craftsmen. By stipulating Spain as the place for binding, the task was converted into a locally executed craft on the peninsula. Regulations, however, did not alter transnational transportation practices and customs officials often destroyed the binding at the Spanish borders to obey the laws.Footnote 162 Transatlantic shipments to the viceroyalties, by contrast, contained mainly ready-bound books, as was already the practice in the trade of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 163 Such procedures for import regulations and local binding crafts reveal the policies of the book market in a colonial context that was the same for Spanish America as for British America.Footnote 164 The extent to which imported books with Spanish binding curtailed colonial manufacture eludes us, as only single names and contracts for bookbinding are known. While there are few references to binding activities and ink making, the scarcity of printing utensils is frequently manifest in the sources.

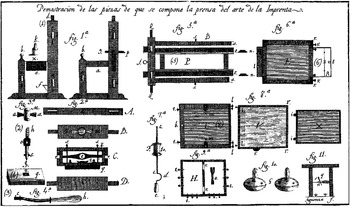

In colonial Lima, missing equipment was a daily affair and printers must have been used to material shortages. Each workshop needed several professional tools for the art of printing (Figure 1.3). The dependence of Peruvian printing workshops becomes clear when studying the provision of metal letters, of which several hundred were necessary to compose a text, and which had to be imported – by law – to Spanish America. Due to the frequent and continuous use of the same types in Peruvian workshops, they became worn and frayed, which affected the clean typeface of the books being printed. Access to new workshop material therefore meant prestige and increasing production, but was far from easy. While the craft of smiths was well established, enterprises to cast letters did not get the permission of the authorities. When the Mexican clockmaker José Francisco Dimas Rangel had cast type himself to open a new printing workshop in the City of Mexico in 1784, the Consejo de Indias – the Council on all things concerning overseas territories – rejected his request, stating that all types and printing tools had to come from Spain.Footnote 165 In the colonial context, importing new workshop equipment was exceptional and required contacts and means.

Figure 1.3 Equipment necessary for the art of printing, depicted in a Spanish printing manual. Juan Josef Sigüenza y Vera, Mecanismo del arte de la imprenta para facilidad de los operarios que le exerzan, Madrid: Imprenta de la Compañía, 1822 [1st ed.1811], 153.