The changing nature of work and workers is a topic that has excited substantial interest and discussion across academic disciplines, organizations, and the popular press. To the degree that statements and proposals “due to the changing nature of work/workers” are supported and therefore, the nature of work/workers has changed, then the approaches commonly used by organizations for attracting, retaining, and rewarding talent must also change in order to maintain a competitive advantage. Similarly, to the extent that work has changed, workers will need to adapt to a workplace that requires different skills, is differently organized, and where the assumptions of the past may no longer hold. This chapter introduces the topic of the changing nature of work and workers, describes common methods used to analyze change, offers a conceptual model of the changing nature of work, and summarizes the major themes that are covered in this handbook.

Introduction

The changing nature of work has been the subject of considerable discussion among scholars, the popular press, and organizations. A perusal of the popular press reveals frequent discussion of the changing demography of the workforce, generational differences at work, increasing levels of income inequality, and technological changes that some argue will fundamentally change the landscape of work. Likewise, scholars from a variety of disciplines, such as economics, sociology, management, and industrial–organizational (IO) psychology, have sought to understand how work and workers have changed and the implications of the changes for their various disciplines. Finally, organizations, their leaders, and employees have navigated these changes and sought ways to better prepare themselves to meet the demands of the modern world of work.

To be sure, the workplace has undertaken significant changes over the centuries, ranging from shifts from agrarian-focused economies to industrialization and shifts to manufacturing, knowledge and service economies. Indeed, it may be reasonably argued that the nature of work is constantly evolving (Murphy & Tierney, Chapter 3, this volume). Yet, many have observed that recent and potentially upcoming changes differ from evolutionary change commonly associated with the changing nature of work (Clauson, Chapter 26, this volume). Rapid advances in technology and a more connected world in particular have already changed workplaces and are frequently proposed to result in more profound changes in the years to come (White, Behrend, & Siderits, Chapter 4, this volume). Indeed, these changes have led some of the world’s leaders to express concern about the future of work. For instance, Bill Gates has argued that “Twenty years from now, labor demand for lots of skill sets will be substantially lower. I don’t think people have that in their mental model” (Bort, Reference Bort2014). Additionally, in his farewell address as president of the United States, Barrack Obama noted, “The next wave of economic dislocations won’t come from overseas. It will come from the relentless pace of automation that makes a lot of good, middle-class jobs obsolete” (Miller, Reference Miller2017). He further described how changes in work can have a pervasive impact on social values, with the “world upended by economic, cultural and technological change.”

In 1999, the National Academy of Sciences issued a call for interdisciplinary research on the future of work. The scholarly community has responded by seeking to analyze the changing nature of work and its implications. Economists have focused their attention on changes in the occupations, critical skills, and wages (Acemoglu & Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011). Sociologists have focused more heavily on changes in the nature of occupations, shifts in the nature of employment relationships, and the growth of precarious work (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2009; Sakamoto, Kim, & Tamborini, Chapter 6). Finally, management research has focused on the way that organizational structures and processes have changed in response to environment changes (Barley, Bechky, & Milliken, Reference Barley, Bechky and Milliken2017). This handbook seeks to bring together insights from these diverse disciplines to inform I-O psychology research and practice.

Much I-O research, like research and practice in adjacent fields, has used the changing nature of work as rationale to study a variety of phenomena, such as organizational commitment in light of perceived increases in job and organizational hopping, extra-role performance behaviors in light of the perceived increasing fluidity of work roles, and work–life conflict in light of the increasing hours worked per household. In addition, I-O psychology research has focused much attention on demographic and generational changes in workforce composition (Costanza & Finklestein, Reference Costanza and Finkelstein2015). Clearly, I-O psychologists believe that changes in the workplace have key implications for modern employees and organizations.

In fact, in considering the trajectory of I-O psychology as a field, changes in the nature of work and workers are at least partly responsible for the growth of the discipline. For instance, in the 1950s and 1960s the United States was grappling with the Civil Rights Movement. In response, the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which, among other things prohibited employment decisions being made on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, and nation of origin. Over the course of the next decade, I-O psychology saw rapid growth, both in terms of the number of practicing I-O psychologists as well as the number of I-O psychology doctoral programs. In particular, organizations increasingly sought the expertise of I-O psychologists to ensure that the methods used to hire and promote employees were valid and legally defensible.

More recently, I-O psychology has seen another stage of rapid growth. In 2014, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics listed I-O psychology as the fastest-growing profession in the United States, and the Department of Labor has listed I-O psychology as a hot job. Why the growing demand? We believe that a key reason that organizations are increasingly seeking out this expertise is to meet the demands of the changing nature of work. Although organizations have long made the claim that “Our people are our most important resource,” the past few decades have seen this platitude become increasingly true. As the economy has shifted from manufacturing and service to more professional or knowledge-based, employees contribute an increasing portion to a firm’s competitive advantage. In addition, as the workforce demands more educated employees who also have more soft skills, there is now a premium on employee talent. Finally, as employees have become more mobile, organizations are now competing with one another over relatively scarce talent. In short, organizations must increasingly find ways to recruit, select, motivate, and retain talented employees in order to maintain their competitive advantage. In this economic environment, the expertise of I-O psychologists and management researchers is vital.

We hasten to note that the interplay between I-O psychologists and the changing nature of work is not new. In 1995, Howard published the edited volume The changing nature of work. This highly influential volume summarized major changes in the world or work, with a specific focus on those changes expected to impact I-O psychology. However, 1995 was a long time ago and much has changed in the past quarter century. For instance, in the mid-1990s, only 0.3% of the world’s population had Internet access, compared to nearly 60% today. Indeed, 42% of the US population had never heard of the Internet (Fox & Rainie, Reference Fox and Rainie2014)! Only around 30% of households in the United States owned a cell phone in 1995, compared to 95% of adults in the United States today. While an obvious change, of course, technology is not the only significant change. The way that employees prepare for retirement and the benefits that organizations offer have also changed drastically. In 1998, around 59% of Fortune 500 companies offered newly hired salaried employees some form of pension plan, compared to only 16% today (McFarland, Reference McFarland2018). In addition, a Gallup survey estimated that in the mid-1990s the average US employee retired at age 57 compared to 61 today (Brown, Reference Brown2013). And, although still only 5% of Fortune 500 companies have a female chief executive officer (CEO), before 1995 only three women had ever headed a Fortune 500 company. Since 1995, 57 women have headed a Fortune 500 company, an exponential increase over earlier years (Yost, Reference Yost2018). In light of change in the nature of work over the past quarter century, it is time to update Howard’s impactful work. This handbook seeks to expand and update Howard (Reference Howard1995) by summarizing the changing nature of work for the modern generation of organizational scientists.

Scope of this Handbook

Heraclitus said that “the only thing that is constant is change.” The same can be said for the world of work. Over time, the nature of work has constantly evolved. In order to make this handbook as manageable and relevant as possible, we have constrained the scope in several ways. First, the chapters focus on changes that have occurred over the past 50 years or so, with a primary emphasis on changes that have occurred over the past 30 years. Although it is certainly interesting and informative to consider changes that have occurred over a longer period, more recent changes are more relevant to understanding how knowledge and practices currently used in the management field should also change. That is, the economies of the world’s economic leaders are certainly very different from the agrarian economy that typified past centuries. However, a comparison to the recent past is more relevant to understanding how the organization and management of modern organizations and their employees should and has changed.

Next, we chose to focus on changes that would have implications for topics and processes associated with management and I-O psychology. That is, we were interested in changes in the work environment, workers, and work itself that influence the strategies used to manage employees. Certainly, changes in the legal landscape such as copyright and intellectual property law have influenced the way that organizations do businesses. But such changes are less likely to influence what employees do on a day-to-day basis and the associated management processes and strategies. Accordingly, such changes are not our primary focus. Instead, we chose to focus on changes that are expected to influence the ways (a) that organizations recruit, select, organize, compensate, motivate, and otherwise manage their employees and (b) that employees manage their relationships with their work organization and their careers.

In terms of the coverage and discussion of changes, the chapters tend to focus on average changes. This is an important caveat. Clearly, it is unlikely that any observed change will be felt the same way across all occupations or workers that comprise the economy. That is, just because on average, workers are more diverse or jobs are more complex, this does not mean that these changes will function similarly across all jobs in the economy. Instead, it is likely that key changes have a differential influence on different sectors, occupations, and industries. Nevertheless, a clear understanding of average changes is of value to researchers and practitioners. A clear understanding of the average changes of the broader economy gives a picture of the broader milieu in which work is done. In addition, it alerts management researchers to key features that are more likely to be at play in any given context. Finally, understanding mean changes is useful in directing attention to contexts that require increased research attention, given their prevalence in the workplace.

Next, the majority of the book focuses on data from industrialized countries. This decision was made out of necessity: which is to say that the majority of the available data on changes in the nature of work stems from industrialized countries. In addition, many of the changes that have been examined or discussed in the management literature pertain to the effects of advanced economies (e.g., changes in organizational structures to meet global demands). This is in no way intended to imply that changes in industrializing countries are less important. To the contrary, industrializing countries will provide an excellent lens through which to directly examine changes in work. We hope researchers will take advantage of this opportunity to collect data and develop theory so that we can better understand how changes in the nature of work impact more and less advanced economies.

Finally, we attempted, as much as possible, to start with a foundation of empirically supported changes. That is, there has been much written about how modern work and workers are different from years gone by. However, much of this lacks empirical support. For instance, it has been alternatively argued among popular press commentators that that millennial employees desire more explicit direction from their supervisors (Reshwan, Reference Reshwan2015) and that this same group of employees primarily desire more autonomy (Notter, Reference Notter2018). Likewise, it has been argued that modern workers are both disengaged (Mann & Harter, Reference Mann and Harter2016) and overengaged (Seppala & Moeller, Reference Seppala and Moeller2018). As with answering any complex question, answers to these do not come easily. But when possible, chapter authors attempted to leverage empirical data to support the changes we describe. However, in some cases this simply is not possible given existing research, particularly when discussing implications of changes. For instance, although we may well find evidence that, on average, jobs are more complex, or the workforce is more diverse, it is often necessary to extrapolate what the implications might be of this increasing complexity and diversity in terms of the recommended best practices and management strategies. Thus, although a primary value of this handbook will be to summarize available empirical literature in terms of changes, an equally important contribution will be to focus attention on needed areas of research.

Methods of Analyzing Change

As the reader may infer from the preceding discussion on challenges accompanying empirical analysis of the changing nature of work and workers, providing empirical analysis of change over time can be a challenging endeavor. There are a few reasons for this difficulty. Foremost is the availability of data. Specifically, in order to examine how work and workers have changed, data dating back a number of years must be obtained. That is, if we want to know whether levels of job satisfaction have increased, on average, relative to the 1970s, then we must have year-over-year job satisfaction data using a measure of satisfaction consistently since the 1970s. In addition, we must have a sample that we can use to compare the version from the 1970s to the present measure that is reasonably similar in order to ensure that sample differences are not the cause of any observed differences in satisfaction. Clearly, it would not even be possible to examine more recently defined constructs, such as engagement.

One approach to providing such comparisons is sample matching. In this method, a historic sample is identified in which a construct of interest is measured during a timeframe of interest. For comparison, a modern-day sample is taken matching the historic sample characteristics (e.g., industry, tenure, demographics, location) and using the same measure, items, and scaling. Matching the sample characteristics is an attempt to ensure that any observed differences are attributable to differences in the focal constructs over time and not differences in characteristics of the sample. Once both samples are collected, a simple mean comparison is conducted to determine whether the mean level of the focal variable has changed over time. Smola & Sutton (Reference Smola and Sutton2002) used this approach to compare generational differences in work values between a sample from a study published in 1974 and the sample they collected in 1999. The primary criticisms of this method concern the potential for a lack of representativeness. Consequently, researchers must be deliberate in collecting the new sample, as observed differences could be due to differences in the samples, rather than differences in the constructs of interest. In addition, a comparison based on two individual samples will typically lack the statistical power to develop strong, generalizable inferences of changes.

Next, researchers have used repeated cross-sectional data to examine changes. In a repeated cross-sectional design, different samples of respondents respond to the same items over multiple years. While this can be accomplished when researchers use their own samples that they have collected over time, more commonly researchers leverage existing large-scale databases such as the General Social Survey (GSS) and the Monitoring the Future survey. The key weaknesses with this approach are that it is contingent on the availability of a sample that dates back an extended period of time and measures the variables of interest with the same items. That is, many of the variables that might be of interest simply are not available in a repeated cross-sectional database. Thus, the researcher is limited by what was measured decades ago and, just as important, how it was measured decades ago. For instance, many of the large national databases such as the GSS use a single item to measure focal constructs. Consequently, researchers must often sacrifice the analysis of scale reliability and (grudgingly) accept the use of single item scales. Although this practice is often resisted by management and I-O psychology researchers, unfortunately it is not possible to leverage these databases unless one is willing to conduct analyses on single item scales. In addition, with large and nationally representative samples, other fields such as sociology and political science have a long history of forming inferences based on single item scales, leading to somewhat of a limit to what we think we know. Despite these limitations, we believe that repeated cross-sectional designs are arguably the best available method to examine time-based changes, as the researcher has access to the primary data, the sample sizes are usually quite large, and in many cases the samples from existing databases such as the GSS are nationally representative. In addition, one can conduct more advanced analyses than with afforded sample matching and cross-temporal meta-analysis.

Specifically, the repeated cross-sectional data allow for the use of the hierarchical Age–Period–Cohort (APC) model (Yang & Land, Reference Yang and Land2006). This model partitions variance into effects associated with respondents’ age, effects associated with respondents’ birth cohort, and effects associated with the time period. This partitioning of variance allows for much clearer interpretation of the nature and source of any observed changes (Yang & Land, Reference Yang and Land2006). Age effects are physiological or developmental changes that occur due to the physiological aging process and are evident in cross-sections of people who are of a certain age, regardless of the time period or generation. For instance, as workers get older, the type of rewards they value may shift away from extrinsic rewards and toward more altruistic rewards. In contrast, cohort effects (or generational effects) reflect common experiences of individuals who undergo similar macrosocial influences throughout their early lives that have a formative impact on their personality, values, beliefs, or other stable characteristics. For instance, individuals who grew up during the Great Depression might be more frugal with their money or have less trust of financial institutions throughout the rest of their lives. Finally, period effects occur when specific events or broad social and historical differences impact people living at a given time, regardless of the person’s age or their generation. For example, as women have increasingly taken more professional work roles and the hours worked per household have increased, it is possible that the mean level of work–life balance has dropped across all age groups and generations. A key limitation of the APC model is that data are often not available that would provide the ability to run this model. For instance, one needs data in which the same question is asked over multiple years over a relatively long period of time and in which the intervals are equally spaced (the same time period between each measurement occasion). Clearly, this limits the ability to use the APC model.

A third approach that involves relying on past research to develop inferences is cross-temporal meta-analysis (CTMA; Twenge & Campbell, Reference Twenge and Campbell2001). Whereas traditional meta-analysis focuses on aggregating effect sizes in order to obtain a summary of the magnitude of association between two variables, CTMA instead focuses on mean levels of the variables of interest. By collecting the means for a focal variable and examining the association between the study-level means and the year the data were collected, it is possible to estimate the degree of change in the focal variable over time. For instance, if the means reported in primary studies have gotten larger in recent years, this would suggest that the prevalence of the focal variable has increased. Recently, Wegman, Hoffman, Carter, Twenge, & Guenole (Reference Wegman, Hoffman, Carter, Twenge and Guenole2018) used CTMA to investigate changes in the core job characteristics and showed that autonomy and skill variety had increased (see also Eisenberger, Rockstuhl, Shoss, Wen, & Dulebohn, Reference Eisenberger, Rockstuhl, Shoss, Wen and Dulebohn2019, for a CTMA examining changes in the employee–organization relationship). CTMA is a valuable tool to examine change, as it does not require the availability of primary data going back a number of years as do repeated cross-sectional designs. In addition, as a meta-analytic procedure, CTMA is a more powerful approach than sample matching, because it summarizes mean levels of a variable across the available literature. On the other hand, like other meta-analysis, CTMA is limited by the available literature. For instance, if a given variable has become less commonly examined in recent years, it would be difficult to conduct a meaningful CTMA on the variable. Similarly, if the commonly used measurement scales to measure a focal construct have changed substantially over the years, it is difficult to determine if changes reflect changes in the construct or changes in the measurement. Finally, CTMA does not allow for a clear determination of whether any observed changes are a function of generation or period effects.

Until now, the methods reviewed have emphasized average changes in the characteristics of work and workers. In other words, typically studies using single sample comparisons, CTMA, and repeated cross-sectional designs focus on the mean level of some characteristic of interest, such as worker values or the core job characteristics. However, another way to view changes in work and workers and a critical next step for researchers is the analysis of changes in the nature of relationships between substantive variables over time (Johns, Reference Johns2006). In this type of analysis, time becomes a surrogate for associated changes in the context. For instance, if work characteristics have become more interdependent over time, then it might be reasonable to hypothesize that interpersonal skills will, on average, be more important determinants of effective performance in recent years. Knowledge of whether commonly studied variables have grown more (or less) important based on their association with key outcomes can provide critical information regarding where organizations should focus scarce resources. Unfortunately, in many cases it will not be possible to directly examine year as a moderator of substantive relationships, such as when existing data are insufficient to support moderated meta-analysis. In such instances, it might be possible to focus on key contextual characteristics that have been previously isolated as increasingly prevalent in the modern workplace instead of year. For instance, meta-analysis might focus on analyzing the influence of interdependence, occupational diversity, or knowledge work on substantive relationships.

In summary, there are multiple analytic tools, data structures, and data sources to facilitate the analysis of the changing nature of work. However, it is also true that providing firm empirical analysis of the changing nature of work poses many challenges to the researcher. Probably the biggest challenge is the availability of data. Although there are datasets available, many of these operationalize key constructs using a single item. Similarly, although cross-temporal meta-analysis provides useful information on construct-level change, there are also important limitations in terms of the ability to make inferences regarding the source of effects. Together, given the challenges in finding data coupled with the importance of understanding how changes can impact organizational functioning, it is important that the research community be receptive to studies that attempt to understand the changing nature of work. In other words, if we want to study and better understand the way the world of work has changed and the implications of these changes, we must also be prepared to accept certain limitations inherent to research in this area (e.g., single item scales or difficulty isolating the source of effects). It is our view that some information on how work has changed, even if it is imperfect, is better than no information at all.

Structure of this Book

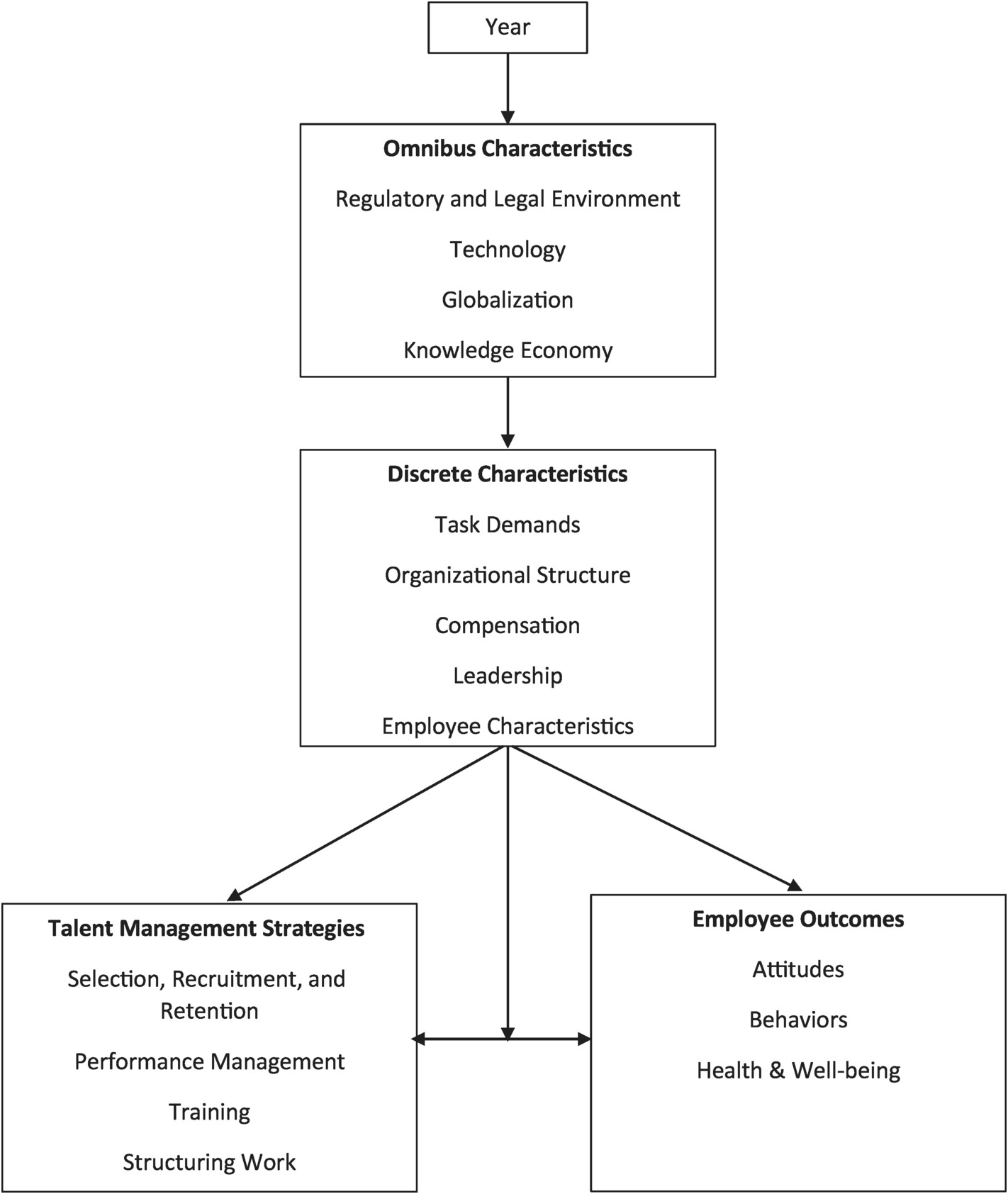

Figure 1.1 depicts a conceptual model of the changing nature of work that serves as the overarching structure for this handbook. In the first section of the book, we lay the foundation for these discussions. Following these introductory chapters, the next two parts discuss the primary features of the conceptual model. In our conceptual model, time is viewed as the focal antecedent of the changing nature of work. The central assumption is that as time has progressed, the world has changed in important ways. In essence, time is treated as a surrogate for a variety of environmental characteristics that form the context of the world of work during a given time period. As time has progressed, broad macroeconomic environmental characteristics have also changed. These broad features are referred to as the omnibus context (Johns, Reference Johns2006). For instance, globalization, changes in the legal landscape, and shifts in the occupational make-up of the economy are all omnibus characteristics that are thought to have changed over the years. Then, these omnibus characteristics are proposed to influence the characteristics of the more immediate work environment, labeled discrete context (Johns, Reference Johns2006). Discrete context includes aspects of a workers’ immediate work environment such as financial incentives, the type of tasks completed, and the nature of the social interactions. As an important note, we include employee characteristics as an element of discrete context. We do so in the spirit of Schneider’s (Reference Schneider1987) Attraction–Selection–Attrition model which proposes that the context of a given work environment is heavily influenced by the characteristics of the employees. In this way, we view changes in the demographics, personality, or values of employees as a potentially salient feature of the work environment.

Figure 1.1 Conceptual model of the changing nature of work.

The third and final section of the book describes how changes in discrete and omnibus context are expected to have a direct effect on both organizational strategies for managing talent and employee attitudes, behaviors, and wellbeing. Conceptually, our assumption here is that, as time has passed and the context has changed, organizational strategies have needed to change with the times in order to most effectively manage talent. As organizations have adapted their strategies to meet changing operational realities, these changes have likely directly influenced employee outcomes, such as their behaviors, health, and well-being. We also expect reverse causality to operate in this model, such that, as employee outcomes have changed along with the context, this has driven organizations to change their talent management strategies. Finally, this model includes a moderating path between discrete environmental characteristics to the relationship between talent management strategies and employee outcomes. This moderating effect is meant to signify that, as time has passed and the context has changed, the effectiveness of various talent management strategies has also changed.

We acknowledge that the boundaries of the organizing framework presented here are semi-permeable. It is likely that a given type of variable, such as leadership, will fall within a multiple of the broader categories. For instance, although leadership is conceptualized in the model as an element of discrete context, leadership can also be viewed as an employee outcome, as we would expect both discrete context and talent management strategies to have a direct effect on the context. In addition, there is likely reverse causation in multiple elements of the model, such that employee outcomes and talent management strategies will shape the discrete context, in addition to being shaped by the discrete context. Thus, our framework offers more of a way of thinking about the changing nature of work than a prescriptive model.

Having outlined the basic structure of this handbook, we now briefly describe each section.

Part I: Introduction. In this chapter, we have sought to set the stage for the discussion of the changing nature of work and workers. We have presented a conceptual model that guides the book and described the methodological approaches and challenges to examining the changing nature of work and workers. The next two chapters of the introduction are intended to help set realistic expectations in terms of what we can and cannot conclude as it pertains to the changing nature of work and workers. In Chapter 2, Costanza, Finkelstein, Imose, and Ravid caution against misattributing sources of changes in worker characteristics to generational differences (as opposed to age-related effects) and especially against the possibility for age-related discrimination that can occur when attempting to apply the findings of generational research. Next, Murphy and Tierney (Chapter 3) argue that changes in the world of work tend to be evolutionary rather than revolutionary and emphasize that changes have not impacted all industries and indeed countries similarly. In doing so, they urge the reader to avoid the temptation to overgeneralize evidence for changes in work.

Part II: What Has Changed? The chapters in this part describe available evidence in terms of what has changed in the world of work. As discussed above, given that there is more easily available evidence for changes in the omnibus context (e.g., social indicators, economic trends), most of the chapters focus on documenting these relatively broad changes. However, where possible, chapters are also devoted to evidence of change in discrete context.

The first three chapters of Part II describe some of the more significant omnibus changes that are referenced when discussing the changing nature of work: technology, globalization, and occupational changes. Technology is arguably the primary driver of a host of the changes that have occurred in the world of work. In Chapter 4, White, Behrend, and Sidertis describe how technology has advanced over time and describe eight characteristics of modern technology. White et al. then offer an insightful strength–weakness–opportunity–threat analysis of technological changes for modern work and workers. The next two chapters describe two key implications of rapidly advancing technology. In Chapter 5, Clott offers an analysis of the impact of changes brought about by globalization. He addresses several issues surrounding the globalized workforce, including global and local talent clusters, labor mobility, access for women, and country-specific efforts to build skilled workforces in technology and financial sectors. In Chapter 6, Sakamoto, Kim, and Tamborini describe how changes in technology have yielded changes in occupational make-up of the economy and skill polarization. As we will see, these changes in occupations have critical implications for the type of jobs available, the skills needed for success, and what workers do on a day-to day-basis.

The next three chapters in Part II describe changes associated with organizations and organizational functioning, including: changes in the legal landscape, changes in income and income inequality, and changes in organizational structure. These chapters are largely focused on the United States. Although we would have liked to include corresponding chapters from different cultures and in different countries, a full accounting of cross-cultural differences in changes in employment laws and income inequality could fill multiple handbooks. We hope that future work can focus on analyzing cross-cultural differences in changes to organizations. In Chapter 7, Hanvey and Sady describe changes in the legal landscape. This chapter expands the field’s traditional emphasis on employment discrimination to include a discussion of modern issues facing society, such as legal challenges associated with employee social media use and the legal implications of a growing number of contract workers. In Chapter 8, Hogler discusses the decline of organized labor in the United States in terms of the legislative and political environment that has precipitated these declines as well as the resulting impact on employee compensation systems and the employee–organization relationship. Next, Jiang summarizes the evidence for a phenomenon that has received much attention in recent years: the growing levels of wage stagnation and income inequality (Chapter 9). She then offers a more micro perspective on this broader social issue by discussing firm-level discrepancies between top management and employee pay. Finally, Sydow and Helfen (Chapter 10) focus on the ways in which organizations structure work has changed over time, from functional approaches to more fluid, matrix-type structures.

In the final group of chapters in Part II, the authors describe changes associated with workers. In Chapter 11, Cheng, Corrington, King, and Ng describe demographic shifts in the workforce, emphasizing the clear trends of a workforce that is quickly diversifying. Next, Lumbreras and Campbell (Chapter 12) discuss generational shifts in worker personality and values. This chapter summarizes the growing literature on generational differences and emphasizes the ways in which changes in employee characteristics have important implications for the climate of modern organizations. In Chapter 13, Perry, David, and Johnson describe changes in work behavior patterns. As technology has advanced and the economy has shifted to a bifurcated economy comprised of service jobs on one end and more complex knowledge work on the other, the way that employees enact the process of work has changed. Ranging from workforce participation to the number of hours spent at work, changes in worker behavior patterns are pivotal to understanding the milieu of modern work.

Part III: Implications for Talent Management and Impact on Employees. In concert, these shifts in the macroeconomic context, organizational structure and operational realities, and employee characteristics and behaviors have yielded a growing recognition that organizations must change the way they do business in order to compete for talent and maintain a competitive advantage. Moreover, they suggest meaningful implications for employees’ day-to-day work experiences and how they react to these experiences. The chapters included in the third and final part describe the implications of the previously discussed changes in omnibus and discrete context for organizations’ talent management strategies and employee attitudes, behaviors, and well-being. Where relevant, the authors summarize evidence for changes in context and then go on to describe how changes in context have necessitated that organizations change their strategies in order to more effectively manage their talent.

The first group of chapters in Part III describes ongoing and recommended changes to several key talent management functions based on changes in the nature of work and workers. In Chapter 14, Lyons, Alonzo, Moorman, and Miller describe the implications for personnel selection, focusing on how changes in context have changed critical knowledge, skills, and abilities, required for effective performance, the types of constructs assessed, and in some cases the approach and methods used in personnel selection settings. As organizations find themselves competing over scarce talent and along with evidence that a handful of elite performers tend to provide a disproportionate contribution to organizational effectiveness (O’Boyle & Aguinis, Reference O’Boyle and Aguinis2012), it is increasingly apparent that an organization’s ability to recruit and retain talent will distinguish successful organizations. In Chapter 15, Cascio describes how approaches to recruit and retain talent differ in the modern world of work. The next two chapters focus on getting the most out of employees once an organization has recruited and selected its workforce. In Chapter 16, Schleicher and Baumann discuss the emergence of the concept of performance management as a contrast to traditional performance appraisal. This chapter presents a meso-level model of the performance management process and describes why the shift to performance management is necessary in the modern world of work. Then, Bisbey, Traylor, and Salas (Chapter 17) discuss how the world of work has impacted training. This chapter focuses on differences in the content of training as well as differences in the model of presentation of formal training programs. Then, Chapter 18 by Michel and Yukl applies the classic contingency theories of leadership in a novel way: to understand how changes in context might necessitate changes in commonly prescribed leader behaviors relative to what was expected in earlier research. Finally, in Chapter 19, Jones, Mohan, Trainer, and Carter describe changes associated with the ways that organizations structure modern work. Their chapter describes the increasing use of teams, with a focus on recent increases in multiteam systems, multifunctional teams, and teams composed of geographically dispersed individuals. There is currently substantial variation in terms of the age of the workforce in the United States. Given evidence for the impact of age on work values and attitudes, simultaneously managing employees of such diverse age range poses unique challenges for organizations. In Chapter 20, Rudolph and Zacher discuss these challenges and outline strategies that organizations can use to manage an age-diverse workforce.

The next set of chapters in Part III revolve around what might be considered employee outcome variables. These are variables that are thought to be impacted by both the discrete context and firm talent management strategies. The central assumption here is that as time has progressed and the world of work has changed, both changes in context and talent management strategies have impacted the experiences, attitudes, and behaviors of employees. In our view, understanding the psychological experience of modern work is critical in directing the attention of researchers and organizations to the needs of modern employees. Further, if employees are increasingly viewed as a source of competitive advantage in the modern economy, then understanding how the typical employee experience has changed is essential to maximize organizational functioning.

In Chapter 21, Wegman and Hoffman describe changes in employee attitudes and engagement and the implications of these changes for maintaining a motivated and satisfied workforce. As the number of dual income families has increased and women have increasingly taken full-time work and professional jobs, managing the demands of work and non-work domains has become a fixture when discussing challenges facing modern employees. Greenhaus and Callanan (Chapter 22) discuss the modern challenge of striking a balance between work and non-work. Expanding some of these issues, Chapter 23 by Sinclair, Morgan, and Johnson describes the toll that modern work can take on employee health and how organizations can respond to reinforce a healthy workplace. In Chapter 24, Howard and Spector consider how employees may use technology to enact dysfunctional organizational and interpersonal behaviors, especially when experiencing stressful workplace conditions. On a related note, some have argued that increased employee mobility and the decline of labor unions and pension plans have yielded a fundamental shift in the relationship between employees and their organization. Shoss, Eisenberger, and colleagues (Chapter 25) evaluate the reasons behind these claims and the implications of the proposed shift in the nature of the employment relationship.

The final set of chapters take a broader view on the changing nature of work. Having outlined existing evidence for changes and the implications of changes, Clauson (Chapter 26) next describes how work might look in the future. Finally, in Chapter 27, Foster and Viale discuss an ongoing shift in the perspective of many organizations that many commentators expect to increasingly define the future: the shift toward social responsibility and sustainability. They describe the potential benefits of this shift in mentality for addressing several societal challenges described by the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The Importance of Understanding Change

In closing, we would like to offer a brief commentary on why it is critical to understand changes in work and workers. The hallmarks of psychological research are to describe, predict, understand, and apply/intervene. We believe that the analysis of the changing nature of work is in line with these goals of psychological research and essential to our mission to enhance organizational and individual well-being.

In terms of description, it is first necessary to describe how the workplace and workers have changed over time. And in fact, the vast majority of management research on the changing nature of work has focused on the overarching goal of description. For instance, studies on changes in worker values, workforce demography, the occupational makeup of the economy, and levels of compensation over time have all sought to better describe the milieu of modern work. This research is a critical first step to understanding the ways that the context in which organizations operate has changed. In doing so, this could reveal critical factors that require research from scholars and intervention from organizations and government.

The next commonly stated goal of psychology is to predict human behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. Here again, a better understanding of the changing nature of work can be instrumental to more accurately predicting employee behaviors at, attitudes toward, and reactions to their work. In other words, to the extent that the micro and macro context surrounding employees has changed, then it seems likely that employee behaviors as well as employee reactions to their work will have changed. For instance, if, on average, work has become more team-based, then greater coordination and interpersonally oriented behaviors will be an increasingly important aspect of success. A recognition of changes in the environment and the influence they have on employees can help organizational leaders more actively anticipate demands on employee behavior or employee reactions to their work environment. Similarly, educational institutions and policy makers can use this information to develop curriculum to ensure that the workforce is ready to meet economic challenges.

Next, the goal of understanding is relevant to the changing nature of work so that organizations and policy makers can implement the most effective response to changes. First, clearly documenting the boundary conditions to changes in work and workers can help determine when a certain strategy is likely to be particularly important. For example, if increases in hours worked per week are only being seen in certain segments of the economy, then occupational health and related public policy interventions can be better targeted to where they are needed. Similarly, understanding the explanatory mechanisms underlying change is critical to implementing effective interventions. For instance, whether observed changes in employee characteristics and perceptions are due to age, period, or cohort effects has critical implications for the appropriate response to changes. If changes in employee values are due to worker age then organizations should emphasize different types of incentives to younger and older employees in the recruitment process. On the other hand, if changes in employee values are due to generations, then the strategies used to incentivize and recruit younger employees in the 1970s would be less effective for younger employees today. Thus, the best-practice recommendations found in management textbooks should change, as should employee recruitment strategies. Finally, if changes in values are due to time periods, then this would suggest that some change has affected the average employee, regardless of their generation and regardless of their age. Accordingly, this would suggest that organizations should change the types of incentives they offer to all employees, not just employees from a certain generation. Although merely one example, it is clear that understanding the source of changes is critical to understanding the appropriate response to observed changes.

Finally, by marshaling research that seeks to describe changes in the nature of work, predict the impact of changes on employee behaviors and attitudes, and understand the locus and boundary conditions of changes, it will be possible to design interventions to help organizations more effectively respond to changes. A key theme in the chapters that follow is that various aspects of work and workers have changed. These changes are wide reaching and include factors such as changes in: the occupations that make up the economy, the demographic makeup of the workforce, the skills required for employees and organizations to be effective, and the impact of work on employee health and well-being. As described in Part III of this handbook, these changes have critical implications for many aspects of how organizations manage their talent. Consequently, rigorous research that seeks to describe, predict, and understand the changing nature of work and workers is critical to informing needed changes in talent management strategies and practices.

In sum, we believe that a clearer understanding of changes in work and workers is critical to I-O psychology research and practice, organizations, and more generally, society. This belief rests on the central idea that as the world changes, individuals and organizations must adapt to effectively meet current challenges. Accordingly, it is our sincere hope that this handbook will help employees and organizations alike to better navigate an ever changing world of work. Furthermore, we hope this work will serve as a springboard for future research on the important topic of the changing nature of work and its implications for work and workers.