Nobody could think himself injured by the drinking of another man, though he took a good draught, who had a whole river of the same water left him to quench his thirst: and the case of land and water, where there is enough of both, is perfectly the same.

All governments need to provide for their people in order to stay in power. But why do some governments produce a higher level of public goods and services than others? Under what conditions do governments provide a high level of public goods?

Studies have attributed the variation in public goods provision to regime type. Most of these studies show that democratic systems perform better than authoritarian ones in producing public goods. They explain that democracies produce more public goods because democratic political processes aggregate citizen preferences whereas authoritarian governments need only cater to the small group in power. According to Amartya Sen, the nature of political systems determines the incentives and interests of governments in formulating and implementing public policies. He reasons that democratic leaders have stronger incentives than authoritarian rulers to put in place public goods, such as disaster-prevention measures, because democratic leaders have to win elections and deal with public criticisms.Footnote 1 As a result, “It is not surprising that no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy – be it economically rich … or relatively poor …”Footnote 2 Comparing China and India, Sen points out that India has not suffered famine since independence in 1946 while China has undergone periods of massive starvation and deaths since 1949, in particular during the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1961.Footnote 4

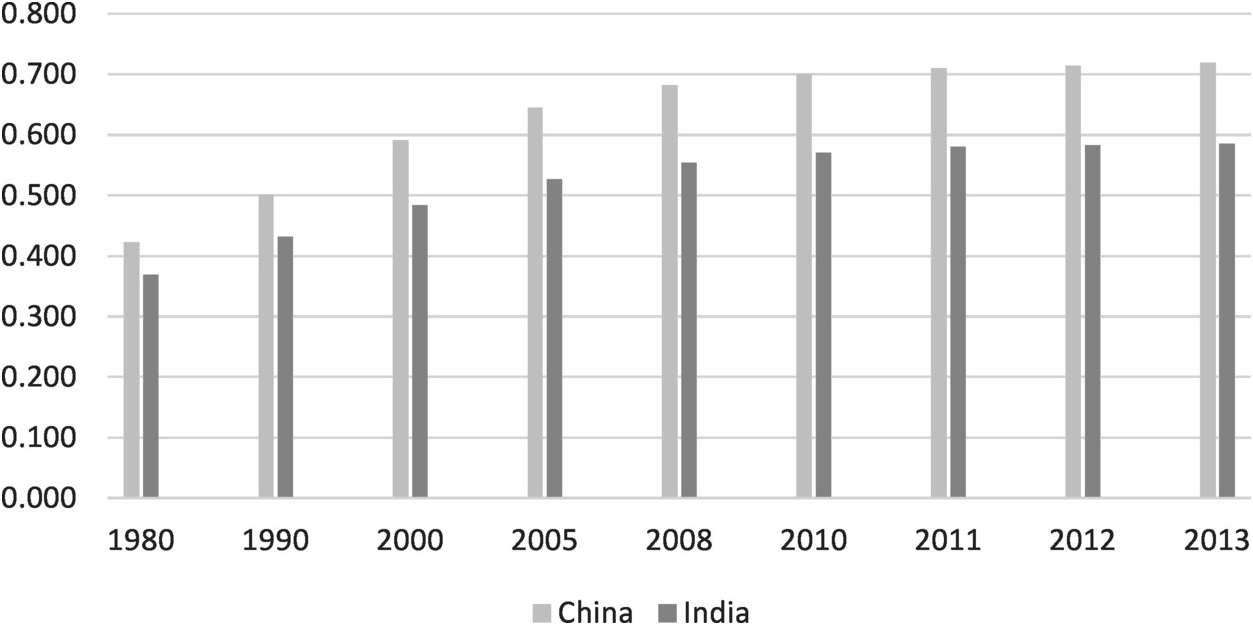

However, contrary to the predictions of theories based on regime type, authoritarian China produces a higher level of public goods than India, the largest democracy in the world. The empirical evidence indicates that Chinese citizens enjoy a significantly higher level of government services than Indian citizens. According to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), China’s Human Development Index (HDI) in 2014 was 0.719 while India’s was 0.586, ranking 91 (categorized as high HDI) and 135 (medium HDI), respectively.Footnote 5 From 1980 to 2013, China’s ranking on the HDI jumped ten places, while India’s only moved up one place. Figure 1.1 traces China’s and India’s HDI from 1980 to 2013. It shows that China’s HDI has been consistently higher than India’s, and the gap between them has grown substantially, even though they were almost at the same level in 1980.

Figure 1.1 China’s and India’s Human Development Index, 1980–2013Footnote 3

Across a series of measures of well-being, such as health and education, China consistently performs better than India.Footnote 6 In terms of the health index, measured as life expectancy at birth, China stands at 75.33 years while India stands at 66.41 years. Total expenditure in health [as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)] steadily increased in China from 4.6 percent in 2000 to 5.2 percent in 2011.Footnote 7 The reverse has happened in India – total expenditure in health (as a percentage of GDP) decreased from 4.3 percent in 2000 to 3.9 percent in 2011.Footnote 8 In terms of the education index, which measures mean years of schooling, China stands at 7.54 years while India stands at 4.43 years. The adult literacy rate in 2012, measured as percentage of the population aged 15 years and older, was 95.1 percent and 62.8 percent in China and India, respectively.Footnote 9

This broad comparison between China and IndiaFootnote 10 does not in any way suggest that China is a redistributive state or a welfare state in the Northern European sense. Inadequate social services and large inequalities continue to be serious challenges for the Chinese state. Rather, the question is why does authoritarian China produce relatively more public goods than democratic India?

The Empirical Puzzle

This study examines one aspect of public goods provision – the supply of drinking water to urban residents. Why do most Chinese urban residents have uninterrupted access to drinking water while only a little more than half of Indian urban residents have access to two to three hours of piped water supply per day?

Data from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (WHO) show that total improved drinking water sources in urban areas are similar for both China and India: access of population to improved drinking water sources in urban areas is 98 percent and 97 percent in 2012 for China and India, respectively.Footnote 11 However, there is a marked difference in terms of access to improved piped water. In China, the proportion of the urban population with access to improved piped water was 95 percent, while in India, only 51 percent of the urban population had access to improved piped water.Footnote 12

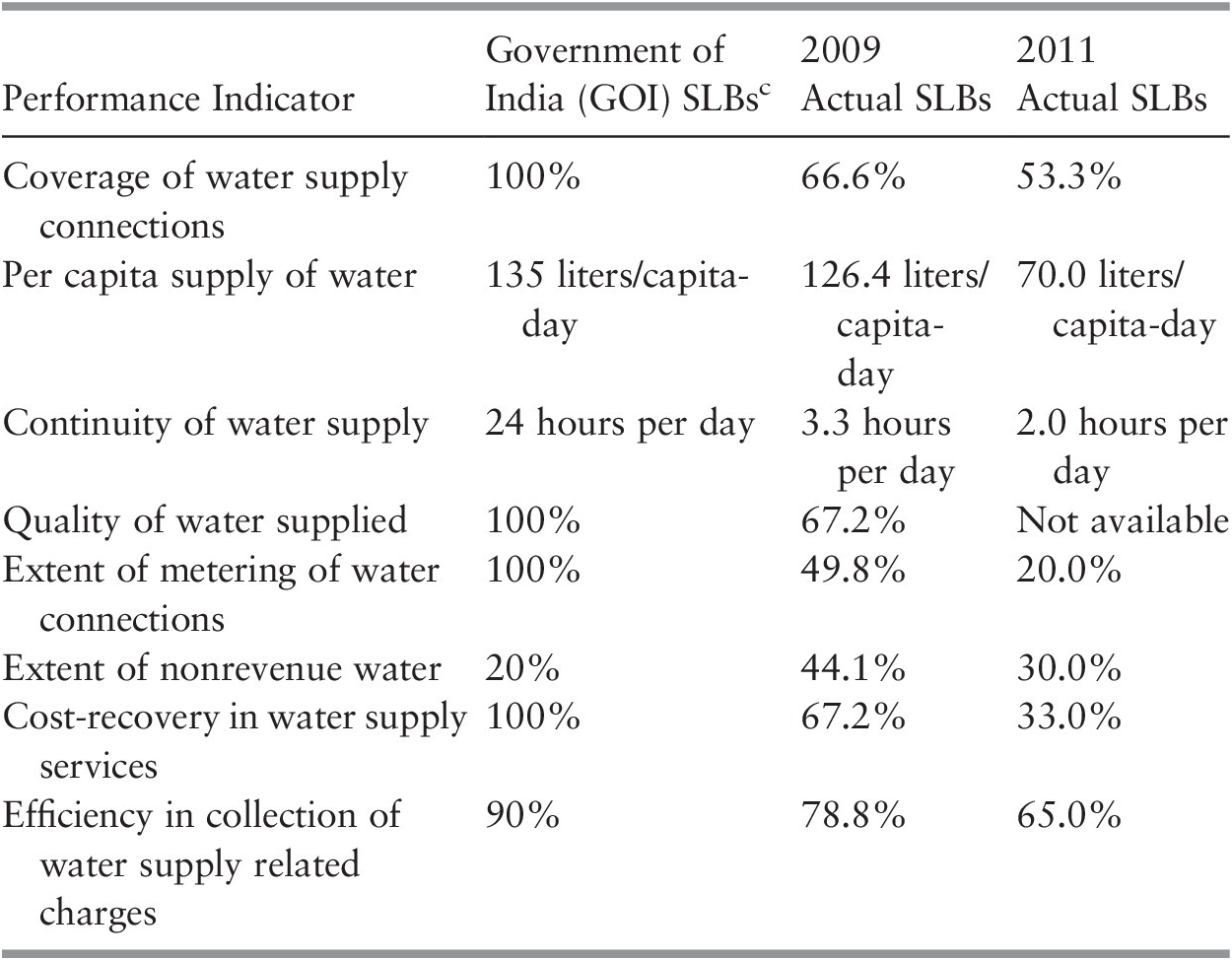

India’s urban population does not have continuous access to piped water (Table 1.1). In 2011, urban residents in India had access to piped water for only two hours per day. Coverage of water supply connections is only 66.6 percent and 53.5 percent in 2009 and 2011, respectively. According to the World Bank, “No Indian piped water supply serving either megacities or smaller towns distributes water more than a few hours per day; this occurs regardless of the quantity of water available for distribution.”Footnote 13 As a result of these deficiencies, Indian urban residents resort to private solutions to their water problems, such as installing water storage units at home, buying water from water tankers, and drilling borewells.

| Performance Indicator | Government of India (GOI) SLBsc | 2009 Actual SLBs | 2011 Actual SLBs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage of water supply connections | 100% | 66.6% | 53.3% |

| Per capita supply of water | 135 liters/capita-day | 126.4 liters/capita-day | 70.0 liters/capita-day |

| Continuity of water supply | 24 hours per day | 3.3 hours per day | 2.0 hours per day |

| Quality of water supplied | 100% | 67.2% | Not available |

| Extent of metering of water connections | 100% | 49.8% | 20.0% |

| Extent of nonrevenue water | 20% | 44.1% | 30.0% |

| Cost-recovery in water supply services | 100% | 67.2% | 33.0% |

| Efficiency in collection of water supply related charges | 90% | 78.8% | 65.0% |

a Survey of service benchmarks conducted by the Ministry of Urban Development in 2009 from 28 cities, spread across 14 states and different city sizes. Arslan Aziz and Saloni Ketan Shah, Public Private Partnerships in Urban Water Supply: Potential and Strategies (Athena Infonomics, May 2012), available from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/186992/PublicPrivatePartnershipsUrbanWaterSupply.pdf (accessed May 16, 2016), p. 13.

b Data reported in March 2011 by 1,493 cities across 14 states. The World Bank, India: Improving Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Services – Lessons from Business Plans for Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Haryana and International Good Practices (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2012), p. 51; The World Bank, Running Water in India’s Cities: A Review of Five Recent Public-Private Partnership Initiatives (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2014), pp. 6–7.

c These SLBs were introduced in 2008 by the Ministry of Urban Development followed by a mandatory requirement by the 13th Finance Commission that current performance levels and annual improvement targets were to be reported by different categories of cities in order to access performance grants from the Finance Commission.

By every performance indicator in Table 1.1, it is clear that India has been performing below the service benchmark set by the Indian Ministry of Urban Development. The high proportion of nonrevenue water, 44.1 percent and 30 percent in 2009 and 2011, respectively, is the result of physical losses, commercial/apparent losses, unbilled consumption, and unauthorized consumption.Footnote 14 What is even more significant is that the performance of India’s urban water sector has deteriorated from 2009 to 2011; of the eight indicators in Table 1.1, India’s performance has slid across seven categories.

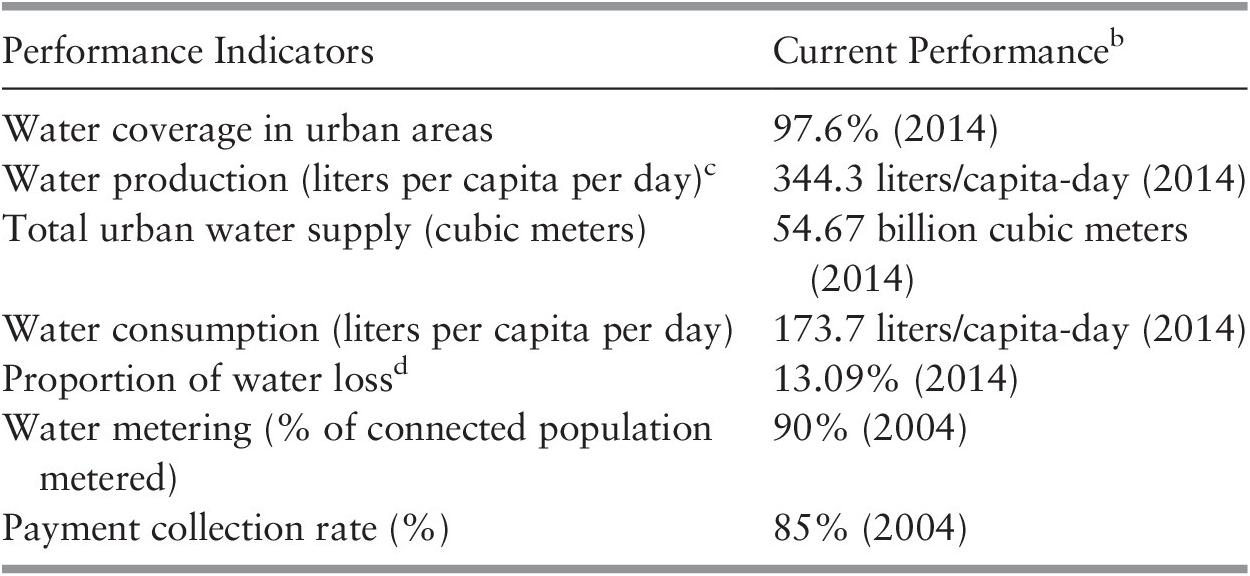

China performs better than India in the urban water sector. Water coverage in urban areas is nearly 98 percent while the national average of proportion of water loss is relatively low at 13.09 percent (Table 1.2). Water production, water metering, and payment collection rate are relatively high. According to a citizen satisfaction survey, the satisfaction of Chinese citizens is highest with the provision of physical infrastructures among all categories of public goods.Footnote 15 Such physical infrastructures include water and drainage systems, roads, railways, electricity, and gas. While public–private partnerships (PPPs) have had difficulty catching on in India, there has been a remarkable increase in PPPs in China. From 2001 to 2012, there were 237 PPPs in water and sanitation in China, accounting for 40 percent of the total number of PPP projects globally; the Chinese population served by private water companies increased from only 8 percent in 1989 to 38 percent in 2008.Footnote 16

Table 1.2 Performance of China’s Urban Water Sectora

| Performance Indicators | Current Performanceb |

|---|---|

| Water coverage in urban areas | 97.6% (2014) |

| Water production (liters per capita per day)c | 344.3 liters/capita-day (2014) |

| Total urban water supply (cubic meters) | 54.67 billion cubic meters (2014) |

| Water consumption (liters per capita per day) | 173.7 liters/capita-day (2014) |

| Proportion of water lossd | 13.09% (2014) |

| Water metering (% of connected population metered) | 90% (2004) |

| Payment collection rate (%) | 85% (2004) |

a Data from PRC Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, China Urban-Rural Construction Statistical Yearbook 2014 (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2015); Greg J. Browder, Shiqing Xie, Yoonhee Kim, Lixin Gu, Mingyuan Fan, and David Ehrhardt, Stepping Up: Improving the Performance of China’s Urban Water Utilities (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2007), p. 12.

b Wherever possible, 2014 data are used. Some data, namely water metering and payment collection rate, are based on 2004 data derived from Browder et al., Stepping Up, p. 12, as 2014 data are not available.

c Water production (per capita per day) is calculated from dividing total urban water supply by urban population of 435 million and 365 days, and converted to liters. Data from China Urban-Rural Construction Statistical Yearbook 2014.

d Percentage of water loss is calculated from total water loss divided by total quantity of water supply. Data from China Urban-Rural Construction Statistical Yearbook 2014.

China’s urban water management framework is not problem-free: water scarcity and pollution remain serious problems. However, China’s performance in delivering drinking water to its urban population is relatively better than India’s and it is at least ahead of India in solving some of its water problems. Why is this the case?

The Argument

I argue that the different types of social contracts (independent variable) that exist in China and India explain the different levels of public goods provision (dependent variable) in the two countries. A social contract encapsulates a certain set of ideas, principles, and precepts that guide and inform the actions of state actors and ordinary citizens of a country, helping to explain the different outcomes in public goods provision. The types of goods that a government prioritizes and provides depend on which set of principles and precepts the government – whether authoritarian or democratic – bases its legitimacy, and whether they accord with the expectations of its citizens. A social contract is therefore based on reciprocity; it is not merely about the basis of legitimacy of a state, which is top-down, but also consists of a corresponding bottom-up set of expectations from the people. Unlike formal institutions, which are explicit and legally constituted, a social contract is an informal institution as it is often implicit and unwritten. It is nevertheless binding because it acts as a constraint on governments. There are consequences, sanctions, or punishments if a government deviates from the terms of the contract. Although the contract is unwritten, it is possible to infer its presence from a country’s constitution, laws, and policies, government statements, political discourses and debates, as well as the narratives that governments create.

Based on the types of social contracts, governments create, design, and establish a corresponding set of formal institutions to help them govern and run the country with the goal of fulfilling their obligations to their people and hence ensuring their legitimacy and survival. They build the requisite formal institutions based on the priorities that are spelled out in their social contracts. Adapting Weberian definitions of an ideal bureaucracy,Footnote 17 I argue that both high capacity and autonomy are critical to the effectiveness of formal institutions in delivering public goods. Social contracts affect institutional capacity by determining how governments allocate resources across different institutions and priority areas. They affect institutional autonomy by circumscribing the space between state institutions, and societal and political interests.

In China, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) ability to deliver fast-paced economic growth, improve living standards, ensure that basic necessities are met, and maintain social stability accords with the expectations of the Chinese people, thus bolstering its legitimacy and enabling it to stay in power. China’s performance-based social contract is, however, not merely about economic performance. There is a moral element in the Chinese social contract that can be traced to the traditional concept of the “mandate of heaven” that is rooted in Chinese history. The presence of a unitary state, albeit with brief periods of fragmentation, has allowed the Chinese concept of performance based on the “mandate of heaven” to perpetuate from the imperial period till today. In this concept of performance, the moral behavior of Chinese officials underpins the delivery of public goods. Chinese officials are deemed to have performed morally when they are benevolent and bring about benefits to the people. Hence, performance in the Chinese context has both material and normative dimensions.

Unlike China’s social contract, which can be traced to the dynastic period, India’s social contract was formed only when a unitary state was established after independence. Two key tenets underpin the Indian social contract. The first tenet is socialism, with emphasis on state ownership and a welfare state. Even though China and India regard themselves as socialist states, “socialism with Chinese characteristics” connotes a flexible and pragmatic approach, suggesting that China’s social contract is better described as based on a concept of performance that has its roots in Chinese history and tradition. India’s brand of socialism does not have the kind of flexibility that China’s has: it has not been able to carry out large-scale reforms of state-owned enterprises as China has done to promote economic growth. Socialist principles bind the hands of political leaders who are not able to deviate from the principle of state ownership by introducing private sector participation. This points to the “stickiness” of socialism as a key tenet of the Indian social contract.

The second tenet is populism, which grew from how democratic participation evolved in India. Building a democratic system on top of a largely rural society led to the growth of populism. Universal franchise was granted in India before an industrial revolution has occurred; as a result, competitive politics led to traditional patronage networks (previously confined to the local rural areas) rising to the state and national levels of government.Footnote 18 More often than not, Indian politicians who wish to win elections and stay in power need to implement populist policies that are at odds with genuine economic reforms. They rely on personal power and charisma to rule.

Intuitively, a social contract that is based on socialism and democratic principles should result in higher levels of public goods provision. After all, governments run the risk of getting voted out of power if they do not mobilize resources, both financial and manpower, to ensure basic standards of living and the well-being of their people. However, India’s experience shows that socialism and populism, by reducing institutional autonomy and capacity, could be hindrances to public goods provision. India has been more successful in implementing the principle of state ownership than in becoming a welfare state. This is where the contradictions between socialism and populism within the Indian social contract become apparent. In order to create a welfare state and implement redistributive polices, strong and autonomous institutions are needed. However, populist leaders, in amassing power for themselves and their personal network, bypass and weaken institutions.

With the Indian state unable to keep its socialist promises of delivering a welfare state, populist policies become useful stopgap measures to stave off popular discontent, acting as substitutes for the welfare aspects of the social contract. These populist measures have a profoundly negative impact on long-term economic development and the delivery of public goods: “… populism limits long-term economic growth … leads to repeated crises and market gyrations, which in turn reduce spending on infrastructure, education, and health care – the building blocks of prosperity.”Footnote 19 Specifically in this study, the New Delhi and Hyderabad state governments were constrained by the populist mandate to give in to demands and protests from a coalition of vested interests that prevented the water utilities in both cities from carrying out unpopular but critical reforms that would help strengthen capacity and autonomy. In addition, socialism, with its emphasis on state ownership, prevents government leaders from tapping into private investments and expertise in reforming public utilities.Footnote 20

By contrast, the emphasis on performance in China’s social contract demands that the government creates the necessary institutions, and carries out policies and reforms that ensure a strong capacity for delivering public goods. Chinese institutions also have autonomy from societal influence and operational autonomy. To help fulfill the mandate of performance in the social contract, Deng Xiaoping began a process of administrative and financial decentralization when he came into power. Decentralization has substantially empowered city governments, which are responsible for the delivery of public goods and services. Unlike the difficulties that the local governments in New Delhi and Hyderabad face in carrying out reforms to their respective water utilities, the case studies on Beijing and Shenzhen demonstrate the capacity and autonomy that both the Beijing and Shenzhen municipal governments have in creating dedicated agencies for managing and coordinating their urban water systems, which helped improve the performance of public utilities. In fact, the Shenzhen Water Affairs Bureau, created in 1993 and the first such body in China, was praised by the Asian Development Bank as a model of reform for urban water management.Footnote 21 Shenzhen was also able to draw on private investments in order to boost the capacity of its existing water supply network. The social contract that the Chinese state established with Chinese society enabled the Shenzhen government and gave it a free hand to deal with Shenzhen’s water issues.

In addition, while India’s social contract requires the Indian government to use its limited resources to cater to the demands of a variety of interests in both the rural and urban sectors, China’s social contract is urban-biased. Jeremy Wallace has shown that cities are critical to the survival of the CCP regime, and hence the CCP’s focus on channeling resources to ensure the well-being of urban workers.Footnote 22 Chinese policies that favor urbanites explain why physical infrastructures and access to basic amenities in Chinese cities are relatively well developed. China does not have the squalid slums that dot the city landscape of many developing countries, including India. Under the terms of China’s social contract, the Chinese government guarantees the daily basic needs of the urban population; the majority of urban residents have job security and access to basic amenities.Footnote 23

A social contract explanation of public goods provision is not unique to China and India. Performance-based social contracts exist, for instance, in East Asian developmental states, including Hong Kong and Singapore, where the legitimacy of governments depends on strong economic growth and delivery of public goods. Populist social contracts can be found in a number of Latin American countries. It is possible to identify other types of social contracts, including those that are liberal in the Lockean sense (the United States), elite-based (neopatrimonial African countries), class-based (the Soviet Union in the Brezhnev era), ideology-based (China under Mao Zedong, especially during the Cultural Revolution), and ritual-based (Bali, Indonesia). Each of these social contracts carries different implications for the government’s ability to provide public goods, with some social contracts inhibiting rather than facilitating the provision of public goods. These other types of social contracts are, however, not the focus of this book, although the concluding chapter will point to them as avenues for future research.

Theories of Public Goods Provision

Regime Type

Scholars who contend that democratic governments deliver a higher level of public goods than authoritarian ones have generally followed two broad lines of argument: rational choice and power distribution. Based on large statistical studies of democracies and autocracies, rational choice theorists premise their arguments on the incentives that drive leaders and the contexts that constrain leaders to produce more public goods.

Martin McGuire and Mancur Olson Jr. assume leaders to be self-interested, utility-maximizing, and incentive-driven individuals who are led by the “invisible hand” in the market place of politics to provide or not provide public goods.Footnote 24 In comparing the effects of the “invisible hand,” McGuire and Olson show that a secure self-interested autocrat who has a long-term horizon, unlike an autocrat whose immediate goal is to redistribute rents to himself in the shortest time frame possible, is incentivized to transform himself from a “roving bandit” into a “public-good-providing king.”Footnote 25 However, according to McGuire and Olson, a majority-rule government whose members have a “more encompassing interest than an autocrat” generates better outcomes in providing essential goods and services than an autocracy.Footnote 26

While McGuire and Olson focus on time horizons, the selectorate theory of Bruce Bueno de Mesquita et al. focuses on the size of the elites to explain public goods outcomes.Footnote 27 According to the selectorate theory, the goal of politicians is to remain in power. To do so, leaders must maintain their winning coalitions. They are therefore agents of electors, and policy choices under all forms of governments are made to promote the interests of an elite group. The crux of the argument of de Mesquita et al. is that the distinction between a dictatorship and a democracy is the size of the elite group relative to the general population. They predict that a government that is controlled by a small elite group is likely to underprovide public goods as opposed to a democratic government, which must be more broad-based.Footnote 28

Apart from incentives, rational choice theorists also examine the context that constrains governments. David Lake and Matthew Baum compare states to “firms that produce public services in exchange for revenue,” stating that “producing services that mitigate market failure is the core of their business.”Footnote 29 Unlike McGuire and Olson’s argument, which sees government leaders in democracies and autocracies as having different objectives and interests depending on time horizons and size of their constituencies, Lake and Baum assume state actors in all forms of governments to have the same goal – the maximizing of rents is the “universal motivation of politicians.”Footnote 30 The only difference between a democratic leader and an autocrat is that the autocrat is able to earn greater rents than a democrat.Footnote 31 Instead of looking at differences in incentives, Lake and Baum emphasize the context in which leaders operate; that is, leaders are assumed to be the same utility-maximizing individuals who are only constrained in rent-seeking by their environment. Democracies, unlike autocracies, have institutions in the form of elections that constrain a state’s monopoly power. The essence of their argument can be summarized as follows:

When barriers to exit and costs of participation are low, as in a democracy, the state will produce as a regulated monopoly, provide larger quantities of goods at relatively lower prices, and thereby earn few supernormal profits or monopoly rents. When barriers to exit and costs of political participation are high, as in an autocracy, the state will exercise its monopoly power, provide few public services, and earn greater rents.Footnote 32

There are four key problems with rational choice arguments. First, rational choice theorists do not take into account the possibility that the resources at the disposal of a government can alter its incentives. Monarchies in Gulf countries are able to provide a high level of public goods because abundant oil resources make it possible for them to distribute wealth across a wide spectrum of society. Resources alone, however, do not mean that public goods provision will be high; the “resource curse” argument demonstrates that the elites of a resource-rich country could accumulate wealth for themselves at the expense of economic and social redistribution. The key difference between these exploitative regimes and the resource-rich autocracies that do deliver a high level of public goods is that the latter are often ruled by traditional monarchs who see themselves as providers and caretakers of their subjects, roles that, at the same time, help them retain the support of their subjects. Hence, in addition to resources, the ethos of a government is a key condition for public goods provision. I will explain in Chapter 3 how China’s social contract, which combines traditional ideas of a benevolent government with the resource capacity of local city governments, results in a relatively high level of public goods provided to Chinese urban residents.

Second, rational choice theorists – in particular the selectorate theory of de Mesquita et al. – assume that the size of the winning coalitions must be broader and bigger in democracies than in dictatorships. In democracies, however, politicians may have to face multiple constituencies and therefore cannot be expected to represent all constituencies. Barbara Geddes’s study on Latin American countries amply demonstrates this point.Footnote 33 In other words, contrary to the findings of de Mesquita et al., the size of the winning coalition could be as small in a democracy as it is in an authoritarian system. Conversely, authoritarian governments may also face large constituencies. In this book, I show that the Chinese and Indian governments need the support of large populations in order to stay in power. The Chinese government needs to cater to the welfare of a large working class in the cities, while India’s limited resources are split between urban and rural areas.

The third shortcoming of rational choice arguments is related to McGuire and Olson’s assumption about time horizons. Both authors assume that majority-rule governments, that is, democracies, have a longer time horizon than autocrats who want to accumulate rents for themselves. This is erroneous as all leaders or political parties would want to remain in power for as long as possible, whether autocratic or democratic. At times, in a democracy, political parties may have a short time horizon when they know that they can be voted out of power in the next election. While Chinese leaders may fit into McGuire and Olson’s description of autocrats with long time horizons, that is, the “public-good-providing king,” their conclusion that a majority-rule government or a democracy will provide higher level of services does not fit into the realities of Indian politics. Indian politicians are often motivated by short time horizons to seek reelection. As a result, the implementation of public policy – which requires a longer time horizon to bear fruit – often falls by the wayside.

Fourth, Lake and Baum assume that elections are the only form of institutions that constrain governments. Institutions that constrain governments are in reality varied and can be formal or informal. For instance, Lily Tsai has shown that informal rules and norms created by solidary groups of high moral standing in rural China are able to constrain government officials into producing public goods.Footnote 34 In my study, I will show that a country’s social contract is a powerful informal institutional constraint on formal institutions and the behavior of political and government leaders.

The second approach to explain the better performance of democracies is to examine the power distribution among political players. According to Robert Deacon, the more even distribution of power among groups in a democracy results in spending on broad-based public goods, while the concentration of power in the hands of a few in a dictatorship favors the transfer of resources to powerful groups.Footnote 35 It makes sense in a democracy to provide broad-based public goods because there are economies of scale to be gained from supplying to a larger population in a system where the government needs to satisfy a large portion of the population.Footnote 36 Deacon’s findings show that democracies exceed dictatorships in public goods provision by about 100 percent for environmental protection, more than 100 percent for roads, and approximately 25–50 percent for safe water, sanitation, and education.Footnote 37

The tendency to provide less public goods when power is concentrated in the hands of a few or a single political party certainly makes sense. However, the assumption that only democracies cater to a large population is flawed because certain types of authoritarian systems, like democracies, depend on a large base for political support and legitimacy. This is particularly true of socialist and communist systems; socialist and communist parties often come into power with working class support and rely on a large working population for legitimacy. China and the former Soviet Union are examples of these authoritarian systems.

There are thus considerable flaws to the arguments that link regime types with government performance in the provision of public goods. Large statistical studies paint broad strokes of regimes and tend to be reductionist. Democratic political systems are not all the same, as extensive studies on democracies have shown.Footnote 38 Likewise, not all autocracies or authoritarian states are the same; their ability to penetrate society and their levers of control vary. It therefore behooves us to unpack the black box of the state. As Joel Migdal succinctly puts it:

… actual states show amazing diversity, straining the idea of a unitary image and making comparison of them a messy business. They vary tremendously in the way they interact with the societies they purport to govern and represent – and in the degree to which they actually do govern and represent. Although state institutions – their executives, bureaus, legislatures, judiciaries, schools, prisons, armies, and the like – may, at first blush, look astonishingly similar…on closer examination these institutions act in myriad different ways. Comparison may privilege form over function.Footnote 39

Contrary to claims that democracies perform better than autocracies, Geddes has shown that democracies do not “routinize the provision of public goods … instead, the achievements of these goods will depend on the specific incentives that face political leaders in different political systems.”Footnote 40 She argues:

In order to maintain their electoral machines, politicians need to be able to “pay” their local party leaders, ward heelers, precinct workers, and campaign contributors with jobs, contracts, licenses, and other favors … politicians’ interest in reelection gives them an interest in responding to the demands of this limited clientele even when it means undermining the goals of the aggregate principal, the citizenry … although a democratic political system should ideally provide politicians with good reasons for supplying public goods desired by citizens whose votes they need to stay in office, in reality the combination of the information asymmetry and the influence of asymmetry between members of internal and external constituencies gives politicians an incentive to respond to the particular interests of some politically useful citizens rather than to the general interests of the public as a whole.Footnote 41

Indeed, there are studies that show that autocracies can do a better job in certain types of redistributive policies. One study by Michael Albertus on land reform in Latin America demonstrates that dictatorships are more effective in land redistribution than democracies.Footnote 42

Hence, the focus on regime type has yielded many anomalies, including the cases of China and India. While regime type may influence performance outcomes, it is not deterministic. Focusing solely on formal constraints loses sight of the informal variables that impact government performance. The conditions for governments to provide greater amounts of goods and services have to go beyond political structures and formal institutions to look at the criticality of agency and the role of informal institutions. Informal constraints are important because even when formal institutions are unstable and weak, informal norms and rules can still act as constraints on government officials to provide public goods.Footnote 43

There is an important and expanding field of literature that examines how informal constraints and institutions such as markets, businesses, social groups, grassroots affiliates, nongovernmental organizations, collective identity, norms, and rituals affect the provision of public goods regardless of the type of regime. Prerna Singh, for instance, demonstrates that the emergence of subnational solidarity or subnationalism in some Indian states, such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu, is more likely to lead to the implementation of a more progressive social policy in education and health with better developmental outcomes.Footnote 44 An increasing number of scholars are also looking at the role of markets in promoting development. Ang Yuen Yuen’s work on how China escaped the poverty trap uses a coevolutionary approach based on the interactions between markets and weak institutions to explain China’s economic development.Footnote 45 In essence, she argues that China first builds markets with weak institutions and then crafts environments that facilitate improvisation among local agents. Kellee Tsai also underscores the role private entrepreneurs play in collaboration with local government officials in employing adaptive informal institutions that helped shape the formal political and regulatory institutions governing China’s political economy.Footnote 46

Other Explanations for Variations in Public Goods Provision

Apart from theories that focus on regime type, scholars have pointed to higher levels of economic development, state capacity, and ethnicity to explain variations in public goods provision. The level of prosperity or economic development is often cited by scholars to account for why some countries produce more public goods than others. Such theories provide an economic rationale to redistribution policies, unlike those that emphasize political systems. Dorothy J. Solinger and Hu Yiyang argue that officials in wealthier cities in China are incentivized differently from those in poorer cities when making decisions to disburse the minimum livelihood guarantee (MLG) funds (dibao), which are social assistance funds aimed at subsidizing households whose average per capita income falls below what is necessary for purchasing basic necessities.Footnote 47 In studies comparing China and India, scholars have argued that China’s higher level of economic development and the fact that China had started liberalizing its economy more than a decade before India have contributed to China being able to produce a higher level of public goods. The argument is that the faster growth of China’s capital stock and the freer flow of labor from the agricultural to the industrial sector in China have enabled China to outpace India,Footnote 48 and thus the concomitant effect on public goods. Some scholars have also attributed the differences in development between China and India to India’s colonial legacy, which has led to India suffering from a lower resource base.Footnote 49

The wealth of a country has an impact on whether its government is able to deliver public goods – a high level of GDP facilitates a government’s efforts to increase spending on public goods. However, there is no direct causal relationship between economic wealth and redistribution policies; greater wealth does not necessarily lead to redistribution policies, as redistribution may not be the priority of governments even if they have the resources. Greater wealth could lead to higher inequalities if the wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few instead of being redistributed to society. The elites of a country may accumulate resources for themselves while the rest of the population remains in poverty. In a system like China’s, in which Chinese officials are not constrained by elections to produce more public goods, why should higher levels of economic development translate into higher levels of public goods? Significantly, scholars have pointed out that in the pre-reform period, the Chinese government had provided a wide range and quantity of urban welfare services that were unusual for a country as poor as China; the achievements in redistribution during this period were made in spite of sluggish economic growth.Footnote 50 China’s provision of public goods is thus not necessarily dependent on high growth rates. Whether public goods are provided goes beyond an economic rationale, as there are political and social ethos, as well as ideational and normative principles involved when governments formulate and implement redistribution policies. Moreover, wealth alone is not sufficient for the successful implementation of redistribution policies. Bruce J. Dickson et al. point out that while higher levels of prosperity have provided resources for local governments in China to tap into, it is their state capacity or how effective local governments are in extracting tax revenues that determines the level of spending on pubic goods.Footnote 51

Some scholars have in fact argued that state capacity is essential for providing public goods. In their study on the implementation of the New Deal in the United States in the 1930s, Theda Skocpol and Kenneth Finegold found that state capacity to carry through interventionist policies explains why redistribution policies can be effectively implemented.Footnote 52 Scholars have also focused particularly on the capacity of local governments. Daniel Ziblatt argues that instead of the demand side or social preferences shaping public goods provision, it is the capacity or the “infrastructural power” of German city governments to supply public goods that determines the level of public goods provided.Footnote 53 In the case of China and India, a common argument for China’s higher level of public goods is that not only does China have greater resources to spend because it is economically more prosperous, but also that it has greater state capacity to do so.

There are two problems with arguments that focus on state capacity. First, there is no guarantee that states with high capacity will provide more public goods; predatory states, for instance, have high extractive capacity.Footnote 54 Second, states with high capacity may not necessarily prioritize the production of public goods. In cultures that traditionally rely on family support or promote self-help, governments may allocate resources and capacity to other priorities while placing less emphasis on the development of a social safety net. My book argues that what determines the prioritization and production of public goods is the terms of the social contract between the ruler and the ruled. States with higher capacity will channel its capacity and resources to producing more public goods if it adheres to the tenets and principles of the social contract.

Arguments based on ethnicity suggest that governments produce more public goods in areas where there is greater ethnic uniformity compared to ethnically heterogeneous areas. For instance, Alberto Alesina et al. found that politicians in cities with an ethnically diverse population spend less on public goods.Footnote 55 This is because voters choose lower public goods when a significant portion of taxes collected from one particular ethnic group is used to provide public goods shared with other ethnic groups. Such an explanation seems plausible in the case of China and India since China is majority Han with a very small ethnic minority, while India is ethnically, linguistically, and religiously diverse. Prerna Singh’s work on subnational solidarity in India certainly falls in line with the ethnic argument. In her study of Kerala, she shows, historically, how the dominance of the Malayali people led to the emergence of Malayali identity and subnationalism, which in turn triggered public support for the state to prioritize social welfare.Footnote 56

There are, however, flaws in theories based on ethnicity. In Andhra Pradesh, the Telugu people is the dominant ethnic group, comprising approximately 83.9 percent (2001 census) of the population.Footnote 57 It is of comparable proportion to the 96.7 percent of Malayali that make up the Kerala population.Footnote 58 However, a cohesive Telugu subnationalism in Andhra Pradesh did not emerge to push the state to prioritize social welfare. In terms of percentage of government capital outlay in education, and health and family welfare from 2000 to 2008, the average in Andhra Pradesh is 11.51 percent and 3.76 percent, respectively, compared to 17.55 percent and 4.86 percent, respectively, in Kerala.Footnote 59 This begs the question: what is the threshold or tipping point in terms of ethnic composition that would likely lead to the emergence of a subnational solidarity, which would, in turn, push the state to devote more resources to public goods? Also, why is subnational identity cohesive in some instances but divisive in others?

Contributions to the Literature

This study makes four contributions to the extant literature. First, it seeks to address the gaps in the existing theories of public goods provision – in particular the deficiencies in regime type theories – by examining a more fundamental layer of state–society relations in the form of a social contract. Even though the book’s argument focuses on incentives and constraints, these incentives and constraints are not seen from the perspective of political systems but rather from the perspective of an informal institution. In addition, as shown in the previous section, levels of wealth, state capacity, and ethnicity do not provide adequate explanations as to why some governments produce more public goods than others. The social contract theory I propose takes into account the political, social, institutional, economic, and normative aspects of public goods provision, thus providing a holistic explanation for variations in the delivery of public goods.

Second, I add to the expanding literature that emphasizes the importance of informal institutions. One can think of a social contract as a large category of informal rules. It provides an overarching framework that binds and undergirds the relationship between state and society. The idea of a social contract has been defined and theorized by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. My book makes a novel distinction from these classic works by defining a social contract as an informal institution, thereby bringing together the fields of comparative politics and political theory. By applying the concept of social contract to public goods, my study is also relevant to the field of political economy and public policy. Politicians and scholars have often referred to a contract between state and society, but such references are general, and the concept of a social contract has been undertheorized. For instance, Linda Cook’s book on the Soviet social contract references the social policies of the Brezhnev and Gorbachev eras.Footnote 60 However, Cook’s book does not place the social contract thesis in a larger theoretical framework or flesh out its components. My book fills an important gap in the literature on what social contracts are and their impact on public goods provision.

Third, my study theorizes the impact of informal institutions on the design of formal institutions that are involved in the delivery of public goods. It examines how the ideational in the form of a social contract shapes and modifies formal structures, leading to different outcomes in the provision of public goods. Formal institutions do not appear or exist on their own; a social contract is the antecedent to formal institutions. Focusing either on formal institutions or informal institutions alone does not provide a holistic and adequate explanation for a complex and difficult issue like public goods provision. My study thus seeks to combine the effects of informal and formal institutions in explaining public goods provision, as opposed to the literature that looks solely at either formal or informal institutions to explain redistribution policies. The causal mechanisms that lead to higher delivery of public goods are demonstrated using rich empirical case studies.

Finally, my study contributes to the growing literature that compares China and India. Studies in this area have focused on the two countries’ developmental models, economic growth, market liberalization reforms, financing, labor, education, environmental, agricultural and industrial policies, growing inequalities, and demographic and migration issues.Footnote 61 Differences in their HDI and economic performance have most often been attributed to differences in their political systems, and higher investment and savings rates in China compared to India, rural–urban migration laws, and investments in education and health. Some scholars have also focused on the development of civil society in China and India to explain differences in levels of prosperity between the two countries, for instance, arguing that the CCP has greater control over civil society and a more compliant labor force than India.Footnote 62 Still others have attributed the differences between them to India’s colonial history and the exploitation of its resources that went with it, as well as the existence of a wealthy diaspora in China’s case.Footnote 63

While these studies are important and illuminating, they often do not go beyond a structural and formal institutional account of the differences and similarities between the two countries, and, as a result, are not completely satisfying explanations. In the area of public goods, for example, studies on urbanization in China and India, and the differing outcomes in urban infrastructure and public goods attribute these differences to the role of local financing and governance structures.Footnote 64 My study addresses a more fundamental and deeper issue: what accounts for the differences in their governance structures and formal institutions? It gives a fresh and holistic account of how the differences in their formal institutions come about and offers a theoretical framework for understanding state–society relations and how they relate to public goods provision in the two countries. For instance, the differences in their social contracts explain why decentralization policies work in China but not in India, and why local government institutions in China have more autonomy and capacity to produce public goods compared to similar institutions in India. In addition, by focusing on cities in the two countries, I offer insights into an aspect of development in the two countries that is less often discussed in the comparative literatureFootnote 65 but which has significant implications for the development of their economies.

Plan of the Book

The book is organized into two parts. Following the introductory chapter, Part I develops the conceptual framework of my argument. Chapter 2 defines key concepts, and details how and why social contracts are an informal institution. It then examines the impact of social contracts on the design of formal institutions, which in turn affects the government’s ability to produce public goods. It also explains my case selection and methodology for testing my theory.

Chapters 3 and 4 apply the conceptual framework to China and India. Chapter 3 fleshes out the key characteristics of the Chinese social contract by examining the basis of legitimacy for the Chinese state and how it is congruent with popular expectations of the role of the government. It then demonstrates how the Chinese social contract leads to institutions with strong capacity and autonomy, particularly at the local government level, to ensure that urbanites have access to essential public services. Chapter 4 applies the framework to India, and traces how socialism and populism became the basis of legitimacy and popular expectations. The chapter shows how the Indian social contract constrains the ability of institutions and actors to deliver a high level of basic urban infrastructure.

Part II provides the empirical evidence that supports my argument. Chapter 5 examines the complex water institutional frameworks in China and India to provide the background to the case studies as well as to demonstrate to readers the difficulties and problems that both the Chinese and Indian governments face in delivering water to urban residents. It compares and contrasts the water institutional frameworks in China and India in terms of bureaucratic structures, laws, policies, and regulations that govern the urban water sectors. The impact of their respective social contracts on their water institutional frameworks is discernible, particularly in the extent of the power and autonomy that is granted to lower levels of government to manage the urban water supply.

Chapter 6 examines how the Chinese social contract enabled institutional capacity and autonomy in Shenzhen and Beijing, which led to the reform of their urban water management frameworks and the restructuring of their urban water industries. As a result of these reforms, Shenzhen and Beijing are able to increase water production, cut down on water losses, achieve better coordination, reduce fragmentation of authority, strengthen regulation of the urban water sector, and improve the performance of their water companies.

Chapter 7 examines how the Indian social contract constrains politicians in New Delhi and Hyderabad from being able to pursue reforms of their water utilities. Institutions have little protection from societal and political pressures. They also do not have sufficient financial and human resource capacity to push through reforms. Such constraints led to state leaders of both cities to backtrack on reforms that could have improved basic goods and services in the longer term. In order to stay in power, state leaders retreated to populist promises of free water and electricity.

The concluding chapter relates the social contract argument to recent world events and summarizes the key arguments of the book. It also examines the applicability of the Chinese and Indian social contracts to other countries, and lists a tentative typology of social contracts. The chapter also argues that while social contracts are persistent and enduring, there are conditions under which they could evolve over time. Lastly, the chapter looks at how the Chinese and Indian social contracts can change in the future.