Chapters 3–5 provide detailed accounts of the nine in-depth case studies and detailed analyses of the UK, German, and Swiss blame game styles. Each chapter includes an additional test case that is situated in the respective institutional context. As explained in Section 1.4, I examine the UK, German, and Swiss political systems in detail because the relevant institutional differences between them are most pronounced. The cases situated in the US political system will be discussed in Chapter 7.

This chapter starts by examining the cases situated in the UK political system. The UK political system, with ‘the mother of parliaments’ at its heart, is famous for its sharp and adversarial political debates (e.g., Moran, Reference Moran2015). One could expect that an adversarial debate style would be mirrored in heated blame game interactions in response to policy controversies. As the blame games covered in this chapter will demonstrate, however, UK blame games do not often produce much more than hot air.

3.1 The Child Support Agency Operation Controversy (CSA)

The Child Support Agency (CSA) operation controversy is about a malfunctioning child maintenance system. The Labour government, under Tony Blair, could afford to leave this distant-salient policy controversy unaddressed for more than ten years without facing any political consequences.

Policy Struggle

In 1991, the Tory government introduced the Child Support Act to address a new policy problem. The steady increase of children born to lone mothers since the 1970s had produced a paradigmatic case of policy drift (Hacker, Reference Hacker2004). The existing policy solution, a court-based system, responsible for child maintenance payments between lone parents and nonresident parents could not keep up with the rising caseload. The CSA, introduced in 1993, was thus commissioned to calculate and collect maintenance payments from nonresident parents and transfer them to lone parents. The maintenance system operated by the CSA was riddled with problems. The CSA used a far too complex formula to calculate maintenance payments. There were no incentives for lone parents to cooperate with the CSA, as maintenance payments were counted entirely against social-security payments. Moreover, the CSA was also advised to take on the cases that had already been successfully settled in court (see e.g., Barberis, Reference Barberis1998; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Hutchinson, Robertson, Wadsworth and Watson2002; Harlow, Reference Harlow1999; King & Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014). This poorly designed maintenance system led to slow and erroneous child maintenance assessments, which meant that many lone parents and their children were not getting the money that they were entitled to. Despite a revision of the Child Support Act and other half-hearted attempts to improve the child maintenance system, the CSA continued to struggle with the problems outlined, and it slowly but steadily accumulated an ever-growing backlog of untreated cases.

In response to shocking media stories1 about lone mothers and children having to live in poverty due to the CSA’s negligence, and pressure from parliamentarians who were bombarded with complaints from constituents, the Labour Party clearly positioned itself with regard to the flawed child maintenance system. In the run-up to the 1997 general elections, it promised a radical reform of the current scheme. A Labour politician involved in developing the party’s policy plans for the CSA, said: “To me, the whole culture of the thing is flawed. It has certainly got to change dramatically.”2 Having won the elections, the new Labour government presented several ad hoc measures and initiated a reform process. It proposed the use of an easier formula for the calculation of payments and the introduction of incentives for lone parents to seek help from the CSA. The implementation of these reform proposals, however, depended on a new IT system, which was not expected to be introduced before 2001.3 The Labour government sold these reforms as a giant step toward eradicating child poverty. Alistair Darling, the social security secretary, proclaimed that it “doesn’t take a genius to work out that a radical shake-up of the CSA is long overdue and that is exactly what the government is planning.”4 Overall, the reform proposals did not attract much criticism, although, already at the time the Liberal Democrats, the second opposition party next to the Tories, urged the government to replace the existing maintenance system instead of painfully and slowly reforming it.5

Blame Game Interactions

In November 2004, after the implementation of the reforms had already been delayed several times, the government finally admitted that the IT system could not be made to work. Untreated cases and complaints continued to pile up. The Sun turned on the “Child Shambles Agency” with a special report.6 In the following weeks, opposition parties urged the government to take control of the problem. The Liberal Democrats, joined by Frank Field, an influential Labour politician who argued that the CSA was “teetering on total collapse,” repeated their calls to abolish the CSA.7 When the prime minister, Tony Blair, commented on the controversy, he admitted that the agency’s failures were unacceptable. Amid blame from opponents and critical media coverage, the CEO of the CSA had to resign. However, the government resisted abolishing the CSA and deflected the responsibility for its problems onto the company charged with the implementation of the IT system and onto the child maintenance system inherited from the previous Tory government.8

In September 2005, opponents initiated a new blame attack when the CSA’s performance worsened further and rumors about its imminent collapse emerged. They increased pressure on the government to act boldly, instead of patching things up, and used the CSA to blame the Labour government for not delivering on welfare issues.9 In response, the government apologized for the poor situation and announced its intention to initiate another root-and-branch reform. Two months later, the prime minister admitted that the CSA was “not properly suited” to its job, but, again, argued that the nature of the task that the CSA was supposed to perform – and which had been concocted by the previous Tory government – was extremely difficult. Also in line with previous blame management, he resisted immediate action but played for time by expressing his intention to wait for reform recommendations from the new CEO of the CSA.10 During this phase of the blame game, media coverage became increasingly critical of the government, which, in eight years, had proved unable to address this policy problem. In November 2005, The Guardian wrote that there “ought to be some kind of official cut-off point, when a government is no longer allowed to blame its cock-ups on the previous government.”11

When in January 2006, the CEO’s reform proposals proved too costly to be implemented, the minister for work and pensions announced that another review of the problems at the CSA would be completed by summer. The government’s sidestepping once again triggered far-reaching criticism from opponents. The Liberal Democrats repeated their calls to abolish the CSA. In addition, the Tories urged the government to leave its bunker mentality and commit itself to fundamental reform.12 The Tory Philip Hammond said that there is “too much at stake for the families currently stuck on the present CSA system for this issue to be, once again, kicked into the long grass.”13

The review commissioned by the minister, as well as a very critical report published by the National Audit Office14 in the summer, put the last nails in the coffin of the Labour government’s reform efforts. The minister for work and pensions subsequently announced that the CSA was to be dismantled and replaced by a simpler and tougher system. However, even this admission triggered criticism from opponents. They called it another move of “rebranding, further delay and more gimmicks.”15 Indeed, the flawed CSA occasionally haunted the Labour government until it was voted out in the 2010 general elections, as it received continued criticism for protracting reforms and not acting boldly enough.

Consequences of the Blame Game

There were no significant consequences following the blame game that accompanied the slow demise of the CSA. Incumbent politicians were never put under pressure and only public managers were forced to resign. Opponents were also unable to make incumbents act boldly. At no point during the blame game did the government change its decision to play for time, patch things up, and instead boldly address the policy problem.16 It was only in November 2008 that the government replaced the CSA with the Child Maintenance and Enforcement Commission, a new nondepartmental body for the organization of maintenance payments.

Context-Sensitive Analysis of Blame Game Interactions

It is quite puzzling that the Labour government could leave one of the most severe and long-lasting policy controversies of the modern British welfare state largely unaddressed without facing any political consequences. Verdicts by opponents and experts suggest that the government had a real choice to address this policy problem. As early as 1999, experts asked for a complete redesign of the system and argued that the CSA could never be made to work properly (Harlow, Reference Harlow1999). To understand the government’s decision to leave the problem unaddressed, one must keep in mind that the problems at the CSA were very difficult to fix and public credit for fixing them would have been rather low because only weak constituencies had a stake in the controversy. When confronted with difficult-to-fix and electorally unattractive policy problems, governments often “choose to rely as far as possible on following whatever they have inherited, so that blame attaches as much to their predecessors in office as to themselves” (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011, p. 20). However, governments only follow this strategy as long as the political costs attached to leaving the policy problem unaddressed do not exceed the costs of boldly addressing it. The consideration of contextual factors explains why these costs remained low for so long and, therefore, tell us why the government could afford to leave this policy problem unaddressed.

Issue Characteristics

Both quality outlets and tabloids intensively covered the CSA controversy. During the blame game, coverage constantly increased. The media reported on the controversy in a scandalizing and emotional way and used shocking examples of CSA mistreatment to illustrate the severity of the policy problem. Additionally, quality outlets occasionally covered the controversy in a problem-centered way, focusing on the intricacies of the child maintenance system. The strong public feedback that can be gleaned from the intensity and tone of media coverage is very much in line with what I expect in distant-salient controversies. The CSA controversy violated several of the public’s core values. Progressives took umbrage at the fact that children and lone mothers, weak and positively viewed target populations (Schneider & Ingram, Reference Schneider and Ingram1993), suffered from the government’s ineptitude. For conservatives, it was problematic that the government left nonresident parents, an epitome of the destruction of traditional family values, and a reason for rising social-security payments, off the hook.17 Although there was a significant amount of affected individuals, which increased over time due to changing demographic trends, only a small portion of society was in contact with the CSA. Since new policies need time to create their own vocal constituencies (Mettler & SoRelle, Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Sabatier and Weible2014), there was no policy experience among the majority of the public. This implies that the design features of the child maintenance system, namely its tremendous technical and logistic implementation effort, slipped from the public’s view. For the ordinary citizen, the CSA controversy was simply about a government that did not succeed in making fathers pay their due share for their children.

During the blame game, opponents repeatedly urged incumbents to boldly address the controversy and criticized them for only announcing gimmicks and reviews. In order to bring the public on their side, opponents concentrated on the salience of the controversy, frequently accusing the government of failing to protect children.18 Incumbents, on the other hand, admitted the existence of a serious problem right from the beginning. They never downplayed the seriousness of the controversy and only cautiously emphasized (modest) performance improvements brought about by reforms. Throughout the blame game, incumbents engaged in patch-up activism and played for time by announcing ever-new reviews into the CSA. To signal their commitment and dedication, they garnished their reform proposals with grand rhetorical announcements. Simultaneously, incumbents amply deflected responsibility and blame onto various entities, namely onto the previous government, onto the IT company, onto the CSA, and onto errant fathers who were unwilling to pay maintenance for their children.19 Overall, public feedback to the CSA controversy was strong and opponents clearly exploited the salience of the policy problem. While the distance of the controversy should have allowed incumbents to cover up the inadequacy of their reform efforts for a while, distance was not the full story behind the government’s inertia toward the controversy. The latter strongly profited from an institutional configuration that protected politicians from blame by diverging it to the administrative level.

Institutional Factors

As outlined in the previous chapter, ministers in the UK political system only resign in a case of personal wrongdoing (Woodhouse, Reference Woodhouse2004). In the present case, it is obvious that the minister for work and pensions was far removed from the problems of one of the department’s several agencies. Restrictive conventions of resignation decreased blame pressure for ministers, as opponents never tried to hold them personally responsible for the flawed child maintenance system. The case further reveals that UK ministers not only profited from restrictive conventions of resignation but also from frequent job rotations at political and agency levels. During the protracted blame game, several politicians held the post as minister for work and pensions. In 2005 alone, a year that covered important blame game interactions, four politicians held the post. Ministers clearly benefited from these frequent job rotations.20 While departing ministers simply disappeared from the blame game, incoming ministers enjoyed a honeymoon period (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011), during which they could ask opponents and the public for time to acquaint themselves with the controversy. Moreover, ministers profited from job rotations at the agency. The resignations of public managers not only helped to signal the government’s indignation but they also allowed it to request a settling-in period for the new public manager, during which the latter could analyze the problem and submit adequate reform proposals. This protracted the blame game and allowed the government to play for time.

During the blame game, the government also profited from low direct involvement in this policy area. Despite the supervisory role of the Department for Work and Pensions, the CSA held significant operational responsibility (Harlow, Reference Harlow1999). Opponents predominantly focused their attacks on the agency, calling the controversy a public administration scandal, instead of a policy failure for which the government should be held responsible.21 Tabloids also framed the controversy as an implementation failure, and they held public managers responsible while only imploring that incumbent ministers address the problems at the CSA.22 The focus on the agency, by both opponents and the media, injected an administration bias into the blame game, making it easier for incumbents to deflect responsibility and to frame the controversy as an implementation failure.

Finally, incumbents also profited from the fragmentation of opponents. While the Liberal Democrats and some interest groups urged the government to abolish the CSA early on, the Tories only attacked the government later in the blame game. Lone mothers were not one of their primary target groups and blame attacks in the early stages of the reform efforts would have rung hollow given the Tories’ responsibility for the Child Support Act. Moreover, Tories were less clear in their concrete policy demands than Liberal Democrats.23 Only in the later phase of the blame game did they join Liberal Democrats and interest groups in asking for the agency’s abolishment. Disagreement among opponents about the right way forward allowed the government to maintain the impression that its reform proposals were an adequate response to the problem because there was no uncontroversial policy alternative on the table. Imprecisions about what constituted a viable alternative to Labour’s reform proposals should have been important for the government during this blame game, especially since there were also audible calls from Labour politicians to abolish the CSA. In sum, an institutional configuration that dispersed attacks from opponents and kept political incumbents out of the firing line explains why the government could afford to neglect calls for boldly addressing the controversy, even in the face of strong public feedback (see Table 2 for a schematic assessment of the theoretical expectations).

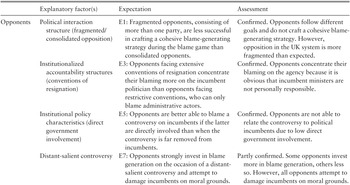

Table 2 Assessment of theoretical expectations in the CSA case

| Explanatory factor(s) | Expectation | Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opponents | Political interaction structure (fragmented/consolidated opposition) | E1: Fragmented opponents, consisting of more than one party, are less successful in crafting a cohesive blame-generating strategy during the blame game than consolidated opponents. | Confirmed. Opponents follow different goals and do not craft a cohesive blame-generating strategy. However, opposition in the UK system is more fragmented than expected. |

| Institutionalized accountability structures (conventions of resignation) | E3: Opponents facing extensive conventions of resignation concentrate their blaming more on the incumbent politician than opponents facing restrictive conventions, who can only blame administrative actors. | Confirmed. Opponents concentrate their blaming on the agency because it is obvious that incumbent ministers are not personally responsible. | |

| Institutional policy characteristics (direct government involvement) | E5: Opponents are better able to blame a controversy on incumbents if the latter are directly involved than when the controversy is far removed from incumbents. | Confirmed. Opponents are not able to relate the controversy to political incumbents due to low direct government involvement. | |

| Distant-salient controversy | E7: Opponents strongly invest in blame generation on the occasion of a distant-salient controversy and attempt to damage incumbents on moral grounds. | Partly confirmed. Some opponents invest more in blame generation, others less so. However, all opponents attempt to damage incumbents on moral grounds. | |

| Incumbents | Political interaction structure (loyal/critical governing majority) | E2: Incumbents that receive support from their party(ies) are more successful in reframing a controversy than incumbents that confront criticism from their own ranks. | Not relevant. Incumbents receive occasional criticism from their party, but this is offset by incoherent attacks from opponents. |

| Institutionalized accountability structures (conventions of resignation) | E4: Incumbent politicians that must comply with extensive conventions of resignation have greater difficulty defending themselves during a blame game than politicians that must comply with restricted conventions. | Confirmed. Opponents never attack incumbent ministers in person because it is obvious to everyone that they are not personally responsible. | |

| Institutional policy characteristics (direct government involvement) | E6: Incumbents are better able to deflect blame for a controversy onto administrative actors if they are not directly involved in the controversy rather than if they are involved. | Confirmed. Low direct involvement allows incumbents to deflect blame onto administrative actors. | |

| Distant-salient controversy | E8: Incumbents take a distant-salient controversy very seriously and confront it by engaging in blame deflection and symbolic activism. | Confirmed. Incumbents take the controversy very seriously and address it by engaging in blame deflection and symbolic activism. |

3.2 The London Underground Renovation Controversy (METRONET)

The London Underground renovation controversy refers to the 2007 bankruptcy of a public–private partnership (PPP) charged with renovating large parts of the London Underground. The ensuing blame game about this proximate-nonsalient controversy did not force Gordon Brown’s Labour government to veer off its course to prominently involve the private sector in public service delivery.

Policy Struggle

After having won the general election in 1997, the Labour government needed to deliver on its promise to end the underfunding of infrastructure. This particularly applied to the London Underground, whose overall condition was the result of years of underinvestment (Jupe, Reference Jupe2009). The government chose to renovate the underground through a so called public finance initiative (PFI). A PFI is a special type of PPP in which the government tenders a public service or project to a private actor, who finances, builds, and often even operates the service or project in return for an annual fee (Flinders, Reference Flinders2005). PFIs are a very controversial public policy tool. Critics emphasize that PFIs frequently fail to transfer risk to the private sector, cannot be properly subjected to parliamentary control, and lock governments into inflexible long-term commitments (Flinders, Reference Flinders2005; Jupe, Reference Jupe2009). Supporters, on the contrary, claim that PFIs promise faster procurement, efficiency savings through private-sector management expertise, risk transfer to the private sector, and the possibility of keeping public debt off-balance. The latter was an especially compelling reason for the Labour government to make PFIs “a cornerstone of [its] modernization programme,”24 as it had previously committed to keep public spending in check.25

In 2001, the government finally tendered the renovation project to two consortia that each founded a special purpose vehicle to carry out the renovation works. Metronet and Tube Lines, as the special purpose vehicles were called, received a monthly service charge for infrastructure improvements and refurbishments from the government and the City of London. The Labour government estimated that the amount of service charges would be approximately £17 billion over fifteen years, and expected that efficiency savings would be around £4 billion from the PPP scheme over the same time.26 Critics of the deals quickly pointed out that the government had made several mistakes when tendering the renovation works. First, the deals were based on overly complex contracts that provided the special purpose vehicles with several loopholes. Second, there was an insufficient risk transfer to the private sector because the government had simultaneously given large loan guarantees to the consortia behind the special purpose vehicles. And third, Metronet only distributed work to consortium members instead of tendering them in a competitive process (Jupe, Reference Jupe2009).

From its inception in 2003 until the collapse of Metronet in 2007, the special purpose vehicles received constant criticism from various sides. In particular, the mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, who had always opposed a PFI solution, and transport unions, criticized the special purpose vehicles for compromising safety in order to hold down costs. From 2005 on, the situation with Metronet became ever more problematic. The Transport Committee27 concluded in an inquiry report that the improvements accomplished thus far were “not in proportion to the huge sums of money flowing through the PPP.”28 In November 2006, rumors emerged about a £750 million cost overrun of Metronet’s budget for the first 7.5 years of the contract. Also the arbiter, a neutral actor in charge of monitoring the PFI arrangement and mediating during conflicts, criticized the management performance of Metronet.

Blame Game Interactions

In June 2007, Metronet went bankrupt when it announced that it expected cost overruns of up to £2 billion.29 The Tories quickly took up the issue by calling for a National Audit Office investigation into Metronet’s collapse and by connecting the failure to Brown, then treasury secretary, and widely considered as the architect behind the PPP scheme.30 However, they did not use the controversy to attack the Labour government for using PFIs. The shadow transport secretary of the Tories said that she did not “believe that taking this contract back in-house will necessarily solve the problems of the [PPP].”31 The other main opponent in the blame game, Mayor Livingstone, did not blame the government after the collapse but quickly signaled his intention to renationalize Metronet by taking over its operations.32 The government sent Ruth Kelly, the transport minister, to explain the collapse of Metronet. During the blame game, Gordon Brown, who had become the new prime minister one month before Metronet’s collapse, remained almost completely out of the blame game and only commented on the controversy once. The transport minister admitted that Metronet’s incentives had not been sharp enough and assured that there were “lessons to be learnt here.”33 However, she defended the PPP policy solution and assured the public that the contracts could be sold back to the private sector. Moreover, she denied any responsibility for Metronet’s collapse and downplayed the taxpayer losses caused by it: “I do not accept that characterization as to the cost to the taxpayer,” which, besides, “is nothing like the figure you are quoting.”34 In his only statement, Brown also reassured the public that another private company would be found to take over Metronet’s contracts.35 Overall, the government clearly stayed on its policy path. It opposed a major investigation into the controversy36 and signaled its intention to keep the private sector involved.

In early 2008, two events gave rise to another round of blame game interactions. The Transport Committee published a very critical report that called Metronet a spectacular failure.37 Moreover, the government was finally forced to accept that its attempts to find a private buyer for the Metronet contract had been in vain. Both the Tories and the Liberal Democrats subsequently blamed the government for its handling of the controversy. The shadow transport secretary of the Tories claimed that the “taxpayer is picking up a £2 billion tab for Gordon Brown’s incompetence when he set up the Metronet PPP. But the total cost of this shambles is still unclear.”38 In response, the transport minister adopted a blame management approach that was very similar to the one observed during the first round of the blame game. She downplayed the losses produced by Metronet’s collapse and the subsequent debt takeover by the government and deflected blame onto Metronet.39 Despite obvious contradictions to previous statements (see later), the government mainly ignored criticism and stayed on the policy path. A last round of interactions occurred in June 2009 after the publication of a critical report on Metronet’s failure by the National Audit Office.40 Opposition parties saw this as a further indictment of Brown’s PPP scheme. However, Sadiq Kahn, the new transport minister, reasserted that PPPs are generally good value for the money, framed Metronet as an exception, and expressed optimism that lessons had been learned.41 Even after December 2009, when the Metronet fiasco finally repeated itself – although on a smaller scale – with the collapse of Tube Lines, the other special purpose vehicle, the blame game did not take a different turn.

Consequences of the Blame Game

The blame game that occurred in the wake of Metronet’s collapse did not lead to political or administrative resignations. Despite the prime minister’s significant personal exposure as the architect of the PPP scheme, the blame game did not negatively affect his approval ratings. While the Department for Transport voluntarily implemented some of the recommendations provided by the Transport Committee and the National Audit Office, there was no major policy change as the Labour government did not adapt its policy position. Despite broad agreement that “Metronet’s failure cost taxpayers millions of pounds and that the structure of the PPP left taxpayers to bear a large financial risk,”42 the government continued to promote PFIs for public infrastructure investments.43 The renationalization of Metronet did not contradict this course, since the government openly claimed that it would have continued to adhere to the private solution had it found a bidder.

Context-Sensitive Analysis of Blame Game Interactions

Why was it so easy for the government to shrug off the collapse of one of the world’s biggest PPPs and continue to use PFIs as its preferred infrastructure investment solution? This must have come as a surprise to experts and the media, who had considered the project’s success as decisive for the government’s future stance on PPPs and PFIs. For example, already in 2003, a professor from the London School of Economics predicted that the problems with the two PFIs would lead to policy change: “I think we’ll look back on the tube as the high watermark of PPPs and PFIs. In years to come, it will look like a huge whale beached by the disappearing tide.”44 In addition to an important policy goal being up for grabs, opponents also had the chance to damage Brown’s reputation, given that he had become prime minister shortly before Metronet’s collapse. As I will show in the following, moderate feedback from the public, a fragmented opposition following different goals during the blame game, and low direct government involvement account for this surprising outcome.

Issue Characteristics

Media coverage suggests that there was only moderate public feedback to the Metronet controversy. Quality outlets consistently covered the controversy, but they did so in a very problem-centered way, illuminating the opaque and complex nature of the PPP scheme. Although this coverage clearly identified Gordon Brown as the architect of the scheme,45 polls show that the controversy did not have a negative effect on his approval ratings.46 The sluggish coverage by the tabloids also suggests that the wider public did not care much about the controversy. Over the duration of the blame game (June 2007–June 2010), The Sun only published twelve articles on the Metronet controversy.47 As The Guardian duly remarked, the Metronet fiasco “has not produced the outrage it should have done.”48

If we consider the proximity of the controversy to the wider public, which was affected both as passengers and taxpayers, the weak public feedback is quite surprising. The endurance of bad service – manifest in delays, overcrowding, and Tube closures due to renovations – was directly felt by many. The losses supposedly accruing onto taxpayers must have appeared enormous to ordinary citizens. While widely diverging numbers were circulating, some sources claimed that the losses to taxpayers could be in the billions.49 The proximity of the controversy prompted opponents to make claims of personal relevance. Already before the collapse of Metronet, the mayor, transport unions, and Labour backbenchers mobilized against the PPP by connecting it to an increase in the number of accidents. By turning the special purpose vehicles into a safety issue, they signaled that the problems with Metronet were relevant to every (potential) passenger. Moreover, opponents also emphasized the financial consequences of the controversy to attract the attention of the wider public. They condemned the huge bill that had been ‘forced upon Londoners’50 and promised to do everything in their power to make sure that losses would not be passed on to passengers in the form of price hikes and would not result in job and pension losses.

The weak feedback to opponents’ claims of personal relevance was primarily due to the low salience of the controversy. While Londoners traditionally care about the Tube and its reliability, the concrete form of public-service delivery is not what arouses public emotions. “The passenger is interested in whether the Tube is running reliably, rather than how that reliability is achieved.”51 A related reason for the low salience of the controversy was the opaque and complex nature of the PPP scheme. The intricacies of PFI arrangements and the unclear consequences of Metronet’s bankruptcy – who would foot the bill, who would take over Metronet’s work and contracts – may have blurred ordinary citizens’ picture of the controversy. After the collapse of Tube Lines, Christian Wolmar, a transport journalist, remarked that one of the “great scandals of the decade is about to come to an end, but because of its complexity and arcane nature, it has passed almost unnoticed – even though the man largely responsible for it occupies No 10 Downing Street.”52 Against this background, opponents first had to establish that the collapse of the PPP scheme was an important political event. In a Transport Committee hearing, opponents therefore attempted to force incumbents to publicly admit that the whole issue was a scandal.53

The low salience of the controversy was advantageous to incumbents. Although the government admitted that there was a serious problem, it exhibited a very confident stance during the whole blame game. The transport minister confidently reframed the controversy by defending PPPs in principle and by qualifying the purported losses resulting from Metronet’s collapse. These reframing attempts clearly aimed to dispel opponents’ claims of personal relevance. Furthermore, the minister deflected blame onto Metronet and rejected calls for an inquiry into its collapse. Another fact that illustrates the government’s confident handling of this nonsalient controversy is that it did not shy away from attracting further criticism by awarding the shareholders of Metronet with new PPP contracts, despite its earlier statements to the contrary. Next to weak public feedback, institutional factors explain why the government could so easily shrug off the controversy.

Institutional Factors

An institutional factor that made it easier for the government to continue with its PFI policy was the fragmentation of opponents during the blame game. While the Liberal Democrats generally opposed PFIs, the Tories were not categorically against them and, unlike Liberal Democrats, they argued for complete privatization. The mayor of London, on the other hand, focused instead on the prize of policy and quickly moved to renationalize operations when the right moment arose, instead of overtly blaming the government for its PFI ventures. Like in the CSA case, opponents’ different priorities prevented the formation of a coherent and visible policy alternative to the status quo.

In addition to incoherent attacks from opponents, the government further profited from a low degree of direct involvement in the policy area. PPPs are usually very complex arrangements and are considered to be one of the main reasons for increasingly blurred accountability and fuzzy governance structures (Flinders, Reference Flinders2005). In the present case, an institutional structure that involved actors at the national and at the local level increased the inherent complexity of the PPP scheme even further. Overall, this led to an administration bias within the blame game. Media coverage suggests that the two special purpose vehicles, the arbiter, and the mayor received most of the public’s attention. During the blame game, opponents did not correlate the controversy with the political incumbent, but instead they focused the majority of their blaming on administrative actors.

A factor that reinforced this effect was the narrow focus of the inquiry reports produced during the blame game. Although the UK political system reliably and frequently produces inquiry reports that can act as blaming occasions for opponents, they usually do not question policy. Instead, they seek to grapple with the implementation structures created by the government. In this case, the reports from the National Audit Office and the Transport Committee did not question the PPP solution in its own right, nor did they compare it to other hypothetical procurement solutions, but rather they focused on technical implementation problems. For political incumbents, this had the welcome advantage that political responsibility was not a main point of debate during the blame game. Moreover, the government also made use of the ample blame deflection possibilities provided by the complex implementation structure. These factors explain why in this case the limited conventions of resignation, on which the transport minister could have relied on to protect herself from the consequences of personal allegations, were not causally relevant. Also, the fact that criticism from the governing majority was audible during this blame game did not carry much weight against the backdrop of low public feedback, incoherent attacks from opponents, and ample institutional blame protection resulting from low direct government involvement (see Table 3 for a schematic assessment of the theoretical expectations).

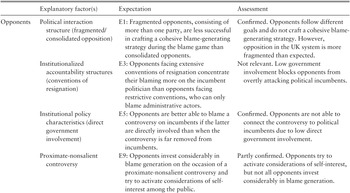

Table 3 Assessment of theoretical expectations in the METRONET case

| Explanatory factor(s) | Expectation | Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opponents | Political interaction structure (fragmented/consolidated opposition) | E1: Fragmented opponents, consisting of more than one party, are less successful in crafting a cohesive blame-generating strategy during the blame game than consolidated opponents. | Confirmed. Opponents follow different goals and do not craft a cohesive blame-generating strategy. However, opposition in the UK system is more fragmented than expected. |

| Institutionalized accountability structures (conventions of resignation) | E3: Opponents facing extensive conventions of resignation concentrate their blaming more on the incumbent politician than opponents facing restrictive conventions, who can only blame administrative actors. | Not relevant. Low government involvement blocks opponents from overtly attacking political incumbents. | |

| Institutional policy characteristics (direct government involvement) | E5: Opponents are better able to blame a controversy on incumbents if the latter are directly involved than when the controversy is far removed from incumbents. | Confirmed. Opponents are not able to connect the controversy to political incumbents due to low direct government involvement. | |

| Proximate-nonsalient controversy | E9: Opponents invest considerably in blame generation on the occasion of a proximate-nonsalient controversy and try to activate considerations of self-interest among the public. | Partly confirmed. Opponents try to activate considerations of self-interest, but not all opponents invest considerably in blame generation. | |

| Incumbents | Political interaction structure (loyal/critical governing majority) | E2: Incumbents that receive support from their party(ies) are more successful in reframing a controversy than incumbents that confront criticism from their own ranks. | Not relevant. Incumbents receive occasional criticism, but the latter does not carry much weight. |

| Institutionalized accountability structures (conventions of resignation) | E4: Incumbent politicians that must comply with extensive conventions of resignation have greater difficulty defending themselves during a blame game than politicians that must comply with restricted conventions. | Not relevant. The minister is never attacked by opponents due to low government involvement. | |

| Institutional policy characteristics (direct government involvement) | E6: Incumbents are better able to deflect blame for a controversy onto administrative actors if they are not directly involved in the controversy rather than if they are involved. | Confirmed. Low direct involvement allows incumbents to deflect blame onto administrative actors. | |

| Proximate-nonsalient controversy | E10: Incumbents take a proximate-nonsalient controversy seriously and address it by mainly adopting reframing strategies and forms of activism. | Partly confirmed. Incumbents take the controversy seriously and address it by mainly adopting reframing and deflection strategies. However, activism is very limited. |

3.3 The Millennium Dome Controversy (DOME)

The distant-nonsalient Millennium Dome controversy involves a national exhibition held in Greenwich, London, during the year 2000 to celebrate the new millennium. The exhibition attracted fewer visitors than expected and cost more than anticipated, resulting in an inconvenient blame game for the Labour government leading up to the 2001 elections.

Policy Struggle

The story of the Dome controversy goes back to 1994, when the Tory government of the time decided to finance public projects celebrating the coming millennium. It was expected that these projects would center around a grand millennium exhibition running throughout the year 2000. To organize and run the exhibition, the Tory government founded the New Millennium Exhibition Company. In June 1997, the incoming Labour government revealed its intention to continue with the project. As became clear later when cabinet memos were leaked,54 the Labour government only made this decision after heavy intra-cabinet disagreement. Some ministers feared that a go-ahead would be too risky and that, once the government endorsed the project, it would not be able to blame the Tories if the exhibition failed. Other cabinet members, among them Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson, his close ally, emphasized the negative consequences of canceling, including a £144 million write-off of investments already made and anticipated blame from the Tories for being cowardly and unreliable. But most importantly, the exhibition was “conceived with a political pay-off in mind.”55 Blair and Mandelson saw a chance to use the exhibition as a symbol for ‘New Labour’, the slogan used by the party to distinguish itself from earlier, less market-friendly versions of the British Labour Party.

After the decision had been made, Mandelson became the minister responsible for the exhibition. He assured the public that the latter would create a lasting legacy and “give an unforgettable thrill” to visitors.56 However, it did not take long for uncertainties regarding the concrete contents of the exhibition to attract negative media coverage. Moreover, the ‘Dome’ (the colloquial name of the exhibition due to the flashy construction hosting it in Greenwich, London) became a symbol for the media when discussing the New Labour phenomenon after eighteen years of Conservative rule. To brace themselves against negative coverage, Blair, Mandelson, and Lord Falconer (Mandelson’s successor as millennium minister in late 1998 after a personal affair forced Mandelson to step down) started a publicity offensive.57 In Tony Blair’s words, the exhibition would be a “triumph of confidence over cynicism, boldness over blandness, excellence over mediocrity.”58 Their statements already foreshadowed the blame-management approach that the government would later adopt during the blame game. They spread optimism by framing the exhibition as a great cultural project on the path to success and asked for unity and support from the public. Despite its timely opening, the exhibition became a heavily mediatized controversy in the run-up to the 2001 elections.

Blame Game Interactions

During 2000, the government was repeatedly blamed for lower-than-expected visitor numbers and for a lack of funding, which had to be plugged with public money to prevent the premature and embarrassing closure of the exhibition. Already in January, revenue losses due to unexpectedly low visitor numbers led to the first additional public cash injection. Amid criticism from the media, the CEO of the New Millennium Exhibition Company resigned.59 Tories and Liberal Democrats quickly criticized this step as a cowardly form of scapegoating, denounced newly introduced measures to increase the exhibition’s attractiveness as quick fixes, and framed the problems at the Dome as emblematic of the Labour government’s overall performance. The Tory leader William Hague asserted that the Dome epitomized “the Labour Government that built it – massive hype, huge amounts of money wasted, long queues and a great disappointment.”60

Another cash injection of £30 million in May triggered a second major blame attack and sparked a public discussion about prematurely closing the Dome. Tories and Liberal Democrats criticized the government for throwing good money after bad and called the exposition a “monument to the vanity and emptiness of New Labour.”61 Labour backbenchers also began to press for a financial inquiry. The government retorted that the cash injection was tied to harsh financial and operational conditions imposed on the management of the New Millennium Exhibition Company. The Guardian duly observed that there were no signs that the government was “prepared to offer any olive branches” to the Dome’s critics.62 In the following months, the Dome was never able to throw off negative coverage for very long. Below-target visitor numbers and rumors about cash shortfalls were duly reported in the media.

In late summer, an all-party parliamentary report that criticized the unwarranted political intrusion into the management of the Dome and two further cash injections of £43 million and £47 million triggered the most intensive phase of the blame game. The Tories pressured Falconer to resign as millennium minister because he had allegedly ignored warnings about the exhibition’s solvency. Moreover, they urged the government to close the Dome and launch an inquiry into its financial management.63 The government reacted to these allegations by once again criticizing the New Millennium Exhibition Company and demoting its new CEO. However, Falconer was kept in place as the minister in charge. Both Blair and Falconer expressed their regret about the situation, but also made rallying calls, claiming that providing cash support to keep the Dome open was “the right course to take.”64 Moreover, they stressed that the exhibition was a clear economic development success. During this phase of the blame game, two Labour government ministers distanced themselves from the Dome.65 In addition, criticism from the media increased significantly. Media outlets expressed their indignation at the government’s unchanged blame-management approach and portrayed the Dome as emblematic of New Labour.

Despite ongoing media coverage, occasional skirmishes about the future usage of the Dome, and the publication of a critical report by the National Audit Office,66 which outlined the problems and mistakes that had led to the underperformance of the exhibition, the government stood firm in its decision until the closure of the Dome at the end of the year. The blame game surrounding the Dome proved unable to harm the Labour government, which won the 2001 general elections in a landslide.

Consequences of the Blame Game

Overall, the consequences of this blame game are as negligible as the consequences of the other two blame games studied thus far. Despite strong attacks directed at political incumbents, resignations only occurred at the managerial level. With the Labour government confidently pulling through with the exhibition until the end of the year, there were no noteworthy policy consequences.

Context-Sensitive Analysis of Blame Game Interactions

The interesting question behind this blame game is why the government, despite strong and personalized attacks, could relatively easily weather the blame arising from opponents and avoid negative consequences in the form of political resignations, a popularity slump, or the premature closing of the Dome. The answer to this question, as the following analysis will demonstrate, primarily lies in weak public feedback and institutional blame barriers that allowed political incumbents to ride out personalized blame.

Issue Characteristics

Contrary to what the media coverage of this blame game suggests, there was only weak public feedback to this distant-nonsalient controversy.67 A closer look at the meticulous and agitated coverage in both quality outlets and tabloids suggests that media outlets overestimated public feedback. Quite a big share of this coverage dealt with artistic aspects instead of with the controversy. This can be read from the fact that coverage was already high in the run-up to the exposition when the blame game had not yet started. Moreover, the media treated the Dome as a symbolic issue to discuss the New Labour phenomenon. Like many cultural projects, the Dome only reached a minority of the public. Many citizens indicated that they did not want to visit the exhibition.68 Those who had bought tickets and went to the exhibition were not negatively affected by the controversy, as the high satisfaction rate of visitors confirms.69 In addition, the financial losses that accrued on to the public as a whole were comparatively minor. Overall, the public’s stance toward the Dome was largely uncontroversial.

Opponents clearly had difficulty generating feedback to this distant-nonsalient controversy. They could only blame the government for money waste, using unspecific truisms like when you put “your money on the wrong horse, you stop betting on it.”70 Opponent claims to personal relevance remained similarly vague.71 Due to strong direct government involvement (see later), incumbents could not stay passive with regard to the controversy. Throughout the blame game, incumbents managed blame by reframing the controversy and by occasionally deflecting responsibility and blame onto the New Millennium Exhibition Company. The government confidently admitted mistakes but never apologized, and instead it attacked the media for bashing the Dome. A statement by Mandelson further reveals that the government realized early on that media coverage was overestimating public feedback: “I think we are getting two quite distinct judgments: one from the public and the other from a section of the media who want to see the dome fail.”72 This helps to explain the quite jovial, self-confident stance that especially Blair and Falconer exhibited toward the controversy – a stance the media likened to an aristocratic attitude of ‘never apologize, never resign’.73

Institutional Factors

Incumbents not only benefited from weak public feedback but also from institutional factors that allowed them to ride out personalized blame. In the present case, the government was directly involved in the policy project. Its decision to endorse the exhibition after taking office in 1997 and to offensively portray it as a symbol for the politics of New Labour produced a strong association between the government and the controversy. The fact that Mandelson and Falconer, two well-known ‘Tony Cronies’,74 held the post of millennium minister further strengthened this association. Strong government involvement allowed opponents to involve political incumbents in the blame game from the start. They urged Blair to apologize and acknowledge responsibility by sacrificing Falconer. The government’s substantial involvement also made it trickier for incumbents to deflect blame. In marked difference to the two previous cases, media outlets and opponents criticized occasional blame-deflection attempts onto the New Millennium Exhibition Company as a form of scapegoating.75

During the blame game about the Dome, opponents acted in concert. Both the Tories and the Liberal Democrats were mainly in line with their requests to the government. As a result, personal options (Falconer to resign or not to resign) and policy options (close the exhibition or keep it open) were very obvious during this blame game. It is clear that the government did not just shrug off these specific requests. As the aforementioned statements by two ministers reveal, at least parts of the government were predisposed to prematurely close the exhibition. On the contrary, occasional criticism from the governing majority should have been less relevant for the course of this blame game because this criticism was offset by occasional support for the exposition from Tories, notably by David Heseltine. As the Guardian put it, “Heseltine’s continuing support has provided the government with important political cover in the face of the Tories’ relentless criticism of the Greenwich attraction.”76

An important institutional factor that allowed the government to keep its minister in office amid coherent and personalized attacks from opponents is the restrictive conventions of ministerial resignation to be found in the UK political system. The public statements of opponents suggest that – at least in cases of high direct government involvement or looming elections – restrictive conventions of resignation alone do not make opponents avoid attacking political incumbents. Opponents tried to compel the minister to resign by convicting him of personal wrongdoings. However, restrictive conventions allowed the government to keep the minister in place, even in the face of strong personalized attacks, since opponents could not formulate convincing accusations of personal wrongdoings on the part of the minister. In sum, weak public feedback to a distant-nonsalient controversy and an institutional configuration that allowed political incumbents to withstand personalized blame allowed the government to come through the blame game undamaged and without having to make any concessions (see Table 4 for a schematic assessment of the theoretical expectations).

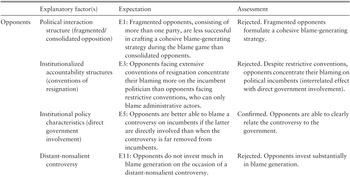

Table 4 Assessment of theoretical expectations in the DOME case

| Explanatory factor(s) | Expectation | Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opponents | Political interaction structure (fragmented/consolidated opposition) | E1: Fragmented opponents, consisting of more than one party, are less successful in crafting a cohesive blame-generating strategy during the blame game than consolidated opponents. | Rejected. Fragmented opponents formulate a cohesive blame-generating strategy. |

| Institutionalized accountability structures (conventions of resignation) | E3: Opponents facing extensive conventions of resignation concentrate their blaming more on the incumbent politician than opponents facing restrictive conventions, who can only blame administrative actors. | Rejected. Despite restrictive conventions, opponents concentrate their blaming on political incumbents (interrelated effect with direct government involvement). | |

| Institutional policy characteristics (direct government involvement) | E5: Opponents are better able to blame a controversy on incumbents if the latter are directly involved than when the controversy is far removed from incumbents. | Confirmed. Opponents are able to clearly relate the controversy to the government. | |

| Distant-nonsalient controversy | E11: Opponents do not invest much in blame generation on the occasion of a distant-nonsalient controversy. | Rejected. Opponents invest substantially in blame generation. | |

| Incumbents | Political interaction structure (loyal/critical governing majority) | E2: Incumbents that receive support from their party(ies) are more successful in reframing a controversy than incumbents that confront criticism from their own ranks. | Not relevant. Criticism from governing majority is offset by occasional support from the opposition. |

| Institutionalized accountability structures (conventions of resignation) | E4: Incumbent politicians that must comply with extensive conventions of resignation have greater difficulty defending themselves during a blame game than politicians that must comply with restricted conventions. | Confirmed. The minister clearly benefits from restricted conventions. | |

| Institutional policy characteristics (direct government involvement) | E6: Incumbents are better able to deflect blame for a controversy onto administrative actors if they are not directly involved in the controversy rather than if they are involved. | Confirmed. Incumbents have difficulty deflecting blame. | |

| Distant-nonsalient controversy | E12: Incumbents do not take a distant-nonsalient controversy very seriously and only scarcely engage in blame management. | Partly confirmed. Incumbents must engage in blame management from the outset, but they exhibit a confident and uncompromising stance. |

3.4 The UK Blame Game Style

In this section, I compare the CSA, METRONET, and DOME cases and subsequently examine a test case to verify and refine the conclusions obtained from the comparison of these three in-depth case studies. These two steps allow me to gain robust and generalizable insights into the UK blame game style.

Political Interaction Structure

In the UK political system, governments are on their own during blame games. In all three cases, the governing majority adopted a rather passive, and at times critical, role, as suggested by the occasional criticism from backbenchers or influential policy entrepreneurs. This is an interesting aspect of UK blame games, especially when considering the strong party discipline for which the UK system is known (Beyme, Reference Beyme2013, p. 187). In Chapter 2, I formed the expectation that incumbents would be interested in a loyal governing majority because bipartisan criticism would signal that a controversy is not just exaggerated but is indeed problematic. The fact that strong party discipline does not translate into cohesive support for the government during a blame game is an important aspect that distinguishes blame games from more routine forms of political interaction. However, the cases also suggest that political incumbents can usually relinquish support from the governing majority because they are in a very comfortable position during blame games.

A first aspect that works in incumbents’ favor is the frequently incoherent attacks by opponents. In the CSA and METRONET cases, the much smaller Liberal Democrats significantly diverged from the Tories in their concrete blaming strategy and in the goals they pursued. This points to another interesting difference between routine political interaction and political conflict during blame games. Due to the media’s interest in poignant statements about a controversy, smaller parties manage to punch above their weight and increase their influence on the framing of an issue during a blame game. For incumbents, this has the welcome effect of clouding the issue, given that policy alternatives to the status quo are not as clear as they could be if they had only come from one opposition party. Incoherence between opponents can create room for the government to stick to its policy goals during a blame game.

Institutionalized Accountability Structures

Another advantageous institutional factor for incumbents is the restrictive conventions of ministerial resignation. In the UK, ministers only resign in cases of personal fault – a constellation of events that is very unlikely in most policy controversies. Moreover, incumbent ministers benefit from the frequent ministerial reshufflings for which the UK system is known (King & Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014). Ministerial reshufflings allow a minister to be taken out of the firing line and the incumbents to buy time since incoming ministers usually enjoy a honeymoon period during which criticism is more muted. Even in cases where personal attacks occur, like in the DOME case, ministers have a good probability of enduring them until the end of the blame game, or until they move to another post in the government machinery. These characteristics of the UK political system make incumbent ministers unpromising targets for individualized blame attacks from opponents. Conventions thus not only influence whether or not an incumbent has to resign but also how much blame the incumbent receives in the first place, as opponents take the attractiveness of incumbents into account.

Institutional Policy Characteristics

The UK’s strong endorsement of agencification reforms has long been discussed under the rubric of accountability deficits, fuzzy governance structures, and depoliticization (Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders and Marsden2015; Flinders & Buller, Reference Flinders and Buller2006; Mortensen, Reference Mortensen2016). The blame games analyzed add important insights to this literature. They show that the low direct government involvement resulting from agencification reforms injects an administration bias into a blame game. In both the CSA and METRONET cases, opponents and the media focused their attention on what was going on at the administrative level, while political incumbents largely remained in the background. The work of parliamentary committees and the reports that they produce reinforce the visibility of the administrative level during blame games. In all three cases, parliamentary committees mainly scrutinized administrative, technical, and managerial problems, while disregarding the question of whether the policy at the root of these problems was flawed. As the media uses these reports as information sources, and opponents use them as blaming opportunities, attention and blame automatically shift to administrative actors and entities. An administration bias results in two advantages for incumbents. First, it allows them to more credibly frame a controversy as an administrative problem, and second, it helps them to avoid a debate about the policy problem(s) behind the controversy. Taken together, restrictive conventions of resignation and low direct government involvement increase the incentives for political incumbents to ride out a policy controversy instead of addressing it.

Test Case: Health Care Targeting Controversy (HCT)

In the following, I test the findings derived from the three in-depth case studies against a fourth case situated in the UK political system, in order to refine and consolidate our understanding of the UK blame game style. The Health Care Targeting Controversy (HCT) is about a performance targeting system that emitted adverse incentives in the health care system and thereby contributed to appalling care standards at an English hospital. The proximate-salient controversy developed into a blame game for the Cameron–Clegg government of the Tories and the Liberal Democrats. During the blame game, opponents urged the government to implement far-reaching reforms and to hold top-level health managers accountable. After briefly outlining the policy struggle and providing a chronology of the blame game, I test whether the influence of institutional factors is in line with the previous findings.

Policy Struggle

Before the turn of the millennium, the first Labour government under Blair introduced a wide-spanning performance targeting system within the National Health Service (NHS). The performance of NHS organizations, such as hospitals or ambulances, was rated, and, based on these ratings, NHS organizations and their managers were either rewarded or penalized (e.g., through bonuses, renewed tenure, budgetary allocations, or public naming and shaming). It soon became clear that this system emitted perverse incentives that led to gaming by NHS organizations and their managers (Bevan & Hood, Reference Bevan and Hood2006). In order to ‘get the numbers right’, some health managers adopted practices that led to the deterioration of care standards. At Stafford Hospital, a culture of gaming led to appalling care standards between 2005 and 2009. Patients were sent home too early, remained untreated for too long, and basic services such as washing, feeding, or pain relief were not properly provided.77

From 2007 on, unusually high death rates at the hospital caught the attention of the oversight system and led the Healthcare Commission to investigate the hospital for the first time. Affected individuals who had lost a relative in the hospital due to poor care began to mobilize. They founded the ‘Cure the NHS’ campaign, which asked for a thorough public inquiry into the controversy and for measures to hold responsible actors accountable. The Labour government under Brown promptly acknowledged the severity of the scandal, apologized to patients and their relatives, and commissioned a first, although limited, inquiry into the controversy.78 The publication of the inquiry report in early 2010 prompted the incoming Cameron–Clegg government to address the controversy again. The new government adopted an approach that was very much in line with that of the previous Labour government. It signaled its determination to address the issue and commissioned a second, but this time more comprehensive, inquiry into the controversy.

Blame Game Interactions

In February 2013, the publication of the second inquiry report triggered the main round of blame game interactions. In response to the report, the Cameron–Clegg government displayed an active and determinate stance. It announced substantial changes to eradicate the “culture of complacency” in the NHS.79 Labour and patient groups, backed by a vociferous media campaign, criticized the government’s response to the report.80 They voiced their doubts in the government’s determination to implement the far-reaching recommendations made in the report and attacked the government for deflecting blame onto practitioners while letting top-level executives at the NHS off the hook. Most importantly, they wanted David Nicholson, the ‘shameless’ man heading the NHS, to resign.81 Nicholson was a particularly blame-attracting figure during the blame game as he had previously served as the regional NHS official charged with overseeing the Stafford Hospital when care standards at the hospital had been at their worst. A considerable number of Tory politicians also urged the government to fire Nicholson.82 Despite these attacks, David Cameron and his health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, backed Nicholson, whom they needed to carry through important – although unrelated – reforms within the NHS. Instead of ceding to the demands for Nicholson’s head, they accused the previous government of fostering “a culture of targets at any cost.”83 After the hot phase of the blame game, patient groups and the media continued to pressure the government for a while so that it would implement the recommendations made in the inquiry report.

Consequences of the Blame Game

Despite the government’s detailed plans of how it wanted to respond to the recommendations in the inquiry report, it fell significantly short of implementing the report’s recommendations. Although the government invoked a raft of smaller changes intended to increase and better monitor quality care at NHS facilities, it opposed important recommendations such as the introduction of minimum staffing levels.84 The reforms adopted by the government did not lead to fundamental change in the targeting system.85 In addition, the personal consequences of the blame game were negligible. Neither politicians nor top-level bureaucrats could be forced to resign.

Test of Preliminary Findings and Summary

In the following, I test whether the political interaction structure, institutionalized accountability structures and institutional policy characteristics influenced this blame game in a way that is congruent with the previous findings.

Political Interaction Structure

Like in the other three cases, the government could not count on unmitigated support from the governing majority during the blame game. Members of the governing majority openly voiced their criticism of the government’s handling of the controversy. Several Tory politicians signed a motion asking for Nicholson’s resignation, despite their prime minister advocating for the exact opposite. In the HCT case, blame generation from opponents was quite coherent and consistently focused on two goals: a comprehensive inquiry into the scandal and personal accountability, not only by practitioners, but also further up the hierarchy within the NHS. This case does not allow for the assessment of whether opponent parties followed different blame-generation strategies and goals because the main phase of this blame game occurred during a time when there was only one opposition party.

Institutionalized Accountability Structures

Restrictive conventions of resignation spared the health secretary from personalized attacks. Since the controversy had occurred prior to his time in office, the health secretary could only be held accountable for his actions in response to the second inquiry report. The latter strongly focused on concrete implementation problems (see later), while not directly addressing the question of political accountability. Holding the head of the NHS to account was thus never politically required. Therefore, the refusal to do so did not lead to fervent attacks on the minister. The behavior of Labour’s shadow secretary for health further confirms that politicians can confidently rebuff demands to step down in the absence of personal wrongdoings. The shadow secretary had been health secretary during the time when the controversy had occurred. During the blame game, when Labour urged the Cameron–Clegg government to fire Nicholson, the government retorted that if someone had to resign, it would be the shadow health secretary, due to his prior political responsibility for the performance of the NHS. In response, the shadow health secretary confidently claimed that he was “fed up” with calls for his resignation.86 This very confident response to a serious controversy indicates the strong blame-insulating effects of restrictive conventions of responsibility.

Institutional Policy Characteristics

Like in the CSA and METRONET cases, low direct government involvement injected an administration bias into the blame game. The head of the NHS quickly became the most prominent figure during the blame game, with media attention and opponent attacks focusing on him. The concrete wrongdoings of practitioners, and, to a lesser degree, oversight neglect on the part of regulatory bodies, took center stage in the public debate. Political actors and their responsibility for the controversy were mostly neglected. The only exceptions to this pattern were occasional hints by the government that the Labour target system lay at the root of the problem. In the HCT case, one can also observe the effect that reports had on reinforcing the administration bias in the blame game. Like in the other three cases, reports played an important role in bringing the controversy to light, and they provided opponents with blame occasions while simultaneously exonerating incumbents from a heated discussion about the design flaws of the targeting system and their eventual correction. As a Labour source confidently put it in response to the Tories’ blame deflection attempts, this “seems to be a pretty shabby and cheap attempt to politicise the [inquiry] report. It made clear that no ministers were to blame.”87 The inquiry report thus served as a depoliticization instrument, allowing politicians to deny responsibility for a policy scheme for which they were ultimately responsible. Overall, the HCT case confirms the finding that low government involvement and restrictive conventions of resignation create a comfortable situation for political incumbents in the UK system; a situation that allows them to tolerate criticism from their own ranks, brace themselves against coherent blame generation from opponents, and resist opponents’ calls for resignation and policy changes.

Summary

Institutional factors in the UK political system make it difficult for opponents to reach their reputational and policy goals during a blame game. Ministers who are usually only in office briefly and who are not personally responsible for a controversy constitute very strong blame shields for the government of the day. The administration bias injected by forms of agencification and reinforced by the work of parliamentary committees and their reports ensures that the ministerial blame shield is often not even checked for its resilience during a blame game. For opponents, low government involvement thus represents a problem amplifier, which makes it even more difficult to get a hold of political incumbents. The latter, in turn, develop strong incentives to ride out or to protract a controversy and leave the underlying policy problem(s) unaddressed. In the cases examined, strong institutional blame protection allowed political incumbents to adopt a consistent blame-management approach instead of hastily changing blame-management strategies throughout the blame game.