The Roots of Undying Hatred

Jacques Offenbach’s posthumous opera Les contes d’Hoffmann had its gala Viennese premiere on 7 December 1881, at the Komische Oper, elegantly refurbished and renamed the Ringtheater. The next day a sold-out house expectantly waited for the curtain to rise on what promised to be the hit of the season. Before it did, the curtain caught fire and the audience panicked. A series of gas explosions left the house in darkness and the doors could not be opened. Early reports estimated the dead at nine hundred; eventually, the number was determined to be three hundred and eighty-four, chiefly from the upper galleries where the cheaper seats were located.Footnote 1

When Cosima Wagner read the news to her illustrious husband over the breakfast table, his response was unruffled: “When people are buried in coal-mines, I feel indignation at a community that obtains its heating by such means, but when such-and-such a number of members of this community die while watching an Offenbach operetta, an activity that contains no trace of moral superiority, it leaves me quite indifferent.”Footnote 2 The casual cruelty of the remark would be stupefying, were it not seen as the culmination of two decades of his resentment of the French composer.

Throughout Cosima’s diaries for the years leading up to the Ringtheater conflagration, Offenbach recurs as a sporadic irritant, like a seasonal rash. In 1870, during the Prussian invasion of France, Wagner expresses disappointment that the German public cannot free itself from Verdi and Offenbach; the next year, he assumes that the students in Zurich failed to invite him to a peace celebration owing to his status as a mere opera composer “perhaps a shade ahead of Offenbach.” A walk in a Dresden park in 1873 is spoiled because the military band is playing Offenbach, who is deplored the following year as one of “today’s monarchs.” In 1875 Wagner becomes very cross when a costumier conveys Princess Hohenlohe’s message “inquiring whether Venus’s costume” in Tannhäuser “should be à la Offenbach”(i.e., sexily revealing) and in 1879 he undergoes a sleepless night in Bayreuth because the clucking in the poultry yard reminds him of the laughing chorus in Orphée aux enfers, heard in Mainz twenty years earlier. His pleasure, in 1880, in reading the African travels of the German diamond-hunter Ernst von Weber is marred by the frequent mention of Offenbach quadrilles. Only the fellow composer’s death the following year gives him some surcease.

The animosity to Offenbach and the French culture he represented was slow in coming. When the young Wagner served his apprenticeship in Würzburg, Magdeburg, and Riga between 1833 and 1839, he delighted in the comic operas of Boieldieu and Auber, taking a “childlike pleasure” in “the craft and insolence of their orchestral effects.”Footnote 3 He long regarded Paris as “the well-spring” of opera: “Other cities are only ‘étapes’ [stepping-stones]. Paris is the heart of modern civilization.”Footnote 4 When he returned there in September 1859, leading the most exiguous existence while he promoted the premiere of Tannhäuser, he found that Offenbach was the rage of the city. According to their mutual Paris acquaintance Charles Nuitter, French translator of Tannhäuser, Wagner, “on the advice of my good friends,” worked on operettas that were never accepted. Indeed, he would have liked the income obtained from waltzes and comic operas, and, for that matter, the popularity as a conductor that Offenbach enjoyed.Footnote 5

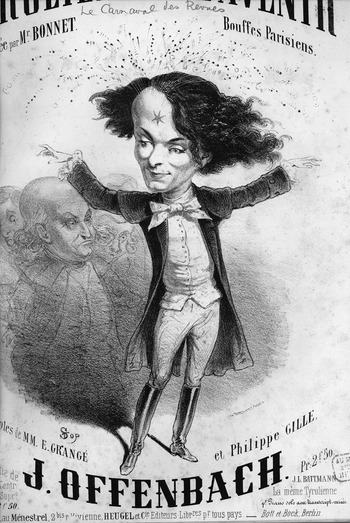

Meanwhile, Orphée aux enfers attained its 228th consecutive performance. At the behest of Napoleon III, a celebratory gala was planned at the Théâtre des Italiens, its centerpiece a musical satire. Le carnaval des revues, which opened on 10 February 1860, featured “The Symphony of the Future,” a farce with words by Eugène Grangé and Philippe Gille and music by Offenbach. After a prologue, the stage discloses Grétry, Mozart, Gluck, and Weber playing dominos in Elysium, awaiting the royalties from their frequent revivals. To while away the time, they interview representatives of new music, including Meyerbeer and the unnamed “composer of the future” (played by the comic actor Hippolyte Bonnet). He promotes a “strange, unheard-of, indefinable, indescribable” music and conducts a deafening “Wedding March,” which parodies the bridal chorus in Lohengrin (interwoven with a banal tune “Les bottes de Bastien”). Its motifs simulate the weeping of the bride and her mother, the wedding banquet, and a donnybrook; Bonnet then sings a “Tyrolienne de l’avenir” (“The Yodel of the Future”), including a sneeze, before the four classical composers kick him offstage.Footnote 6

2.1. Bonnet as Wagner, appalling classical composers, in La symphonie de l’avenir. Caricature by Stop at the head of the sheet music, 1860.

Shortly before Le carnaval opened, Offenbach had been naturalized, so that it was his first produced work as a French citizen. Wagner consequently saw him as a renegade who had sold his birthright for a mess of potage. For his part, Offenbach, despite his working relationship with the translator Alfred von Wolzogen, an opponent of Music of the Future, had no particular animus against Wagner. Nor were the French literati hostile to Germans during this period; they popularly characterized them as phlegmatic beer-drinkers and dreamy metaphysicians. Revues typically parodied current fads and fashions. This sort of teasing was common in Parisian artistic circles. Offenbach, as a foreigner and a Jew, had had to acclimatize himself to it early. His own spirit of mischief, perhaps steeped in Rhineland traditions of Roman holiday and commedia dell’arte, reveled in it. Meyerbeer never took offense at Offenbach’s frequent pokes at “grand opera.”Footnote 7 Wagner, less secure in his career, was thin-skinned, however. The three concerts he had managed to conduct in Paris had been attacked in print by Berlioz just prior to Le carnaval, which made its ridicule all the more stinging. The debacle of Tannhäuser at the Paris Opéra on 13 March 1861 (with Offenbach, Berlioz, and Gounod in the audience),Footnote 8 and the ensuing bad reviews, mockery in the press, and a deficit that threatened debtor’s prison, convinced Wagner that Offenbach was his enemy, first, because he actively propagandized against him, and then, because Offenbach’s own success spoiled the taste of the age for Wagnerian music. The French, he would decide, preferred dance tunes to harmonics, virtuosity to true worth.

As a result, Wagner temporarily channeled his ambition to be a pan-European genius to the narrower goal of writing music to express the German spirit. He allied himself more closely with the chauvinistic ideals of the aging Vormärz movement which held both the French and the Jews in contempt and promoted a nebulous Germanic freedom. At the very time when its sympathizers were campaigning for a purified Teutonic culture to be secured by national unity, Offenbach’s operas were packing German theatres. This raised the hackles of the radical patriots even as it scandalized the artistic conservatives. The eminent tragic actor Eduard Devrient read the libretto of La chanson de Fortunio and parsed its moral as follows: “I’m wanton [liederlich], you’re wanton, he was wanton, we will be wanton.” “What a situation for taste nowadays!”Footnote 9

Across the Rhine

In view of later political events, it is ironic that Berlin, capital of Prussia, still a small garrison town of half a million inhabitants, offered Offenbach his first German successes. After his one-acts had appeared at the Kroll Theater, F. W. Deichmann, manager of the Friedrich-Wilhelm Theater, sensing a winner, offered him a contract even for the operas he had not yet written. Between 1860 and 1872, fourteen of his works appeared there in German translation, the innuendo pointedly projected across the footlights by sultry Marie Geistinger.Footnote 10 During this run of Offenbachian hits, Wagner, after fifteen years of non-performance, enjoyed only two premieres (Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger), both in the Bavarian capital of Munich. Munich, conservative and Catholic, had inveighed against Offenbach. When La belle Hélène and Barbe-bleue appeared there, the newspapers waxed indignant. The Volkstheater production of the former was condemned as

The most hideous monster of our time, made 99 per cent of muck and one percent of wit … A play which endeavors to stimulate the grossest sensuality … which finds its audience only thanks to the smuttiness and indecency of its contents … It is a curse laid upon the French literature of adultery, that it must perforce produce a Belle Hélène, in which adultery is depicted ad oculos on stage.Footnote 11

A police report explained that “owing to the primitive and brutal sensuality of the Munich public, the indecent innuendo produces a greater and more dangerous impression that it would among blasé people, such as the Parisians and the Viennese.”Footnote 12

In Vienna, a more sophisticated center of German-speaking art, Offenbach’s pieces were all but naturalized, thanks to the brilliant adaptations of Johann Nestroy and the saucy renditions of Josefine Gallmeyer.Footnote 13 For Wagner, however, the Austrian capital, where his music-dramas were reputed to be unplayable, was beneath contempt: home of his harshest critic, Eduard Hanslick, it so swarmed with Jews that Wagner dubbed the city “half Asian.” In an essay of 1863 he rebuked the Wiener Hofoper for wasting cultured German musicians on vapid operas. The following year Matteo Salvi, the Hofoper’s manager, postponed the Austrian premiere of Tristan und Isolde to bring forward that of Offenbach’s new German fairy opera Die Rheinnixen. Wagner was infuriated, not only because of the delay, but because he had a draft of his own treatment of Rhine maidens in his desk drawer.Footnote 14 Nothing in Offenbach’s piece takes place under water, but there is a last-act flooding of the Rhine engineered by elves and naiads to distract the pursuing soldiery from the fugitive lovers. A finale in which the Rhine overflows its banks? Did Wagner feel pre-empted or was he influenced despite himself? In the face of these affronts, like Dickens’s Mr Podsnap, he dismissed the Austro-Hungarian capital with a wave of his arm, and wrote to his eight-year-old son, in a regally Victorian tone, “Wir sind gar nicht zufrieden mit Wien, and gedenken sehr bald abzureisen [We are in no way pleased with Vienna and intend to leave it very soon].”Footnote 15

For Wagner, the new German spirit, permeated as it was by Prussian militarism, was to be “Spartan,” a culture of stalwart ephebes and sagacious elders, chaste, idealistic, and Apollonian. As Joachim Köhler has pointed out, this rose-colored, rather pederastic vision has a long tradition in Germany, stretching from Winckelmann to Platen; in the 1860s, many besides Wagner and Nietzsche subscribed to it. “Whereas the love between man and woman is by its nature self-centered and hedonistic,” Wagner wrote, “that between men represents an affection of a far higher order.”Footnote 16 The epitome of heterosexual sensuality, animalistic, licentious, and materialistic, was the Jew, the antithesis to the New Man.

Jews in Music

In his essay of 1865, “What Is German?,” Wagner attributed the decline of German culture to the Jews and sought salvation in the values of the “characteristic German psyche.”Footnote 17 In line with his political stance, he reissued his obscure 1850 pamphlet “Jewishness in music” in an expanded form in 1869, the year that Die Meistersinger and Offenbach’s Les brigands both had their premieres. Whereas the earlier version had attacked chiefly the “serious musicians” Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn, the new recension put forth Offenbach and the popularity of his frivolous operas as prime example. Even his well-known mispronunciation of French is implied. The Jews may well master the language of a country in which they

lived from one generation to another, but they will always speak it like a foreigner, like a language they have acquired, not been born with … The Jews are capable only of confused and empty imitation … never of true poetic language or true works of art.Footnote 18

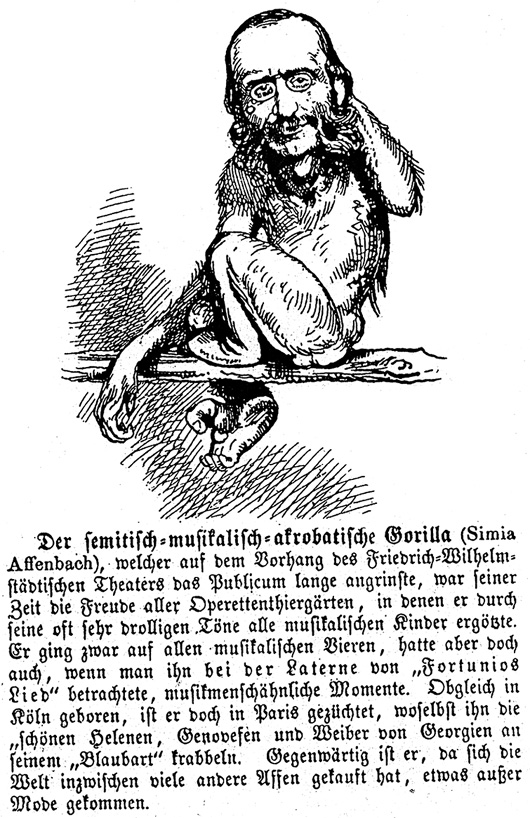

Offenbach had already suffered a few anti-Semitic slurs in his adopted country. The music critic Paul Scudo, an equal-opportunity castigator, mounted attacks on Berlioz, Wagner, Verdi, Liszt, and Gounod; but in dismissing Offenbach he invoked the “fatal brand” of the Semitic race which debarred the composer from beauty and feeling. However, the many French caricatures, without sparing Offenbach’s nutcracker profile and lanky physique, invariably show him triumphant, crowned, bemedaled, applauded by disembodied hands (“l’opinion publique enthousiasmé”). German caricatures emphasize his “Semitic features” and make no reference to his talent. A typical cartoon in the Leipzig Puck (1876) shows him as “Der semitisch-musikalisch-akrobatische Gorilla (Simia Affenbach?)” [a pun on the German “Affe,” ape], grinning through the bars of the Friedrich-Wilhelm Theater.Footnote 19

2.2. “The semitical-musical-acrobatical gorilla (Simia Affenbach),” Leipzig Puck (1876).

The envy of Offenbach that fueled Wagner’s Judophobia in his notorious essay is even more to the fore in a Posse or farce he wrote in November 1870 while victory in the Franco-Prussian War was still being contested.Footnote 20 The first draft was entitled The Capitulation. A Comedy by Aristo. Phanes: in it the Prussians surrender to Offenbach, the “international negotiator.” Wagner tried to persuade his protégé Hans Richter to write music for it in the style of Offenbach, insisting that this “uncommonly appealing” skit “belongs to the real folk theatre.” Wagner’s stooping from high culture to popular burlesque implies a desire to vie with Offenbach on his own terms, in Thomas Grey’s words, “‘consuming’ him, cannibalizing an alien musical-theatrical genre in a gesture of covert cultural imperialism.”Footnote 21 After sketching a handful of numbers, Richter declined to follow through.Footnote 22 When the singer Hans Betz begged off submitting it to a suburban Berlin theatre (too expensive to produce, he claimed), Wagner retitled it A Capitulation. A Comedy in the Manner of Antiquity. Once the French had surrendered at Sedan in January 1871 and Ludwig II of Bavaria asked the King of Prussia to accept the imperial crown, Wagner laid the playlet aside, but included it in his collected works two years later. His preface justified this as an attempt to reform German popular taste away from French models.

Although the preface characterizes the skit as “harmless and jolly,” Wagner’s attribution of it to a dead Greek and then to “E. Schlossenbach,” along with his own reluctance to write its music, indicates a tacit awareness that it may go too far. Set during the Siege of Paris, it caricatures the leading French statesmen, along with Victor Hugo, who emerges from the prompter’s box and brags that he has navigated the sewers à la Jean Valjean to secure provisions. France is to be saved by finding suitable ballerinas for a newly opened Opéra. While Gambetta flies off in a balloon in search of them, the National Guard repels an infestation of rats that turns into a corps de ballet (a pun on rat de l’opéra, slang for a ballet girl – Wagner may have been avenging the Parisian imperative that he provide a ballet for Tannhäuser). An invasion of German impresarios needs to be repelled, so Offenbach is invited to lead a quadrille. The prologue declares, sarcastically, “everything requires true genius and a natural gift, both of which we gladly conceded to Herr Offenbach in his departure.” In the play’s finale, he is introduced, cornet in hand, as “the most international individual in the world, who ensures us the intervention of all Europe! Whoever has him within his walls goes eternally undefeated and has the whole world for a friend! – Do you know him, the miracle man, Orpheus emerged from the Underworld, the venerated pied piper of Hamelin?” (The reference to Offenbach’s “internationalism” foreshadows the anti-Semitic charge of “rootless cosmopolitanism” during the Dreyfus affair, in Nazi propaganda, and in Stalin’s “doctors’ plot.”) The chorus then intones,

This lampoon glanced off its target and boomeranged, severely harming Wagner in French musical circles for some years. So did his reminiscences of Auber, written at this time, in which the French composer was ironically praised for “the pseudo-classical polish through whose glamour none but the sympathetic Parisian initiate can penetrate to the substratum that alone interests him in the long run,” i.e., obscenity. It was for Auber’s heir Offenbach to glorify “the warmth of the dunghill wherein wallow all the swine in Europe.”Footnote 24 “Filth” (Schmutz) became Wagner’s shorthand for Offenbach. Just as the expanded essay “Jewishness in music” of 1869 had shocked Hans von Bülow, Franz Liszt, and music-lovers in Paris and Vienna, so now devoted French Wagnerians washed their hands of their idol. An organized demonstration followed an 1876 performance of the music from Götterdämmerung in one of Jules Pasdeloup’s Concerts populaires and Pasdeloup swore off Wagner for a couple of years.

The Matter of Internationalism

Offenbach’s alleged “internationalism” did him no good either. For the duration of the war there had been a boycott of his music in the major cities of Germany, where rumors ran that he was maligning his homeland. In August 1870, he had to write to the Berlin publisher Albert Hofmann “It is a lie that I wrote a song against Germany … I would take it as an infamy to write a mere note against my first fatherland, the land where I was born, the land where I have so many close relatives and very good friends.”Footnote 25

Yet in Paris, he was considered a turncoat. Four years before the Franco-Prussian war, his immensely popular La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein had been co-opted by Bismarck in his campaign to unite Germany under Prussia. After the victory over the Austrians at Sadová, when the Prussians were annexing or mediatizing petty German states, the jubilant Iron Chancellor had crowed (from Paris, no less) “We are getting rid of the Gérolsteins, there will soon be none left. I am indebted to your Parisian artistes for showing the world how ridiculous they were.”Footnote 26 This sardonic acknowledgement that La Grande-Duchesse had abetted the establishment of the new German Empire appalled Offenbach. A letter of March 1871 protests “I hope that this Wilhelm Krupp and his dreadful Bismarck will pay for it all. Ah! – awful people, these Prussians! … I will never visit that damned country again.”Footnote 27 The Prussians returned the compliment. The Friedrich-Wilhelm Theater, for over a decade the home of Offenbach’s operas in Berlin, produced nothing from his hand in the 1870s and 1880s.Footnote 28 When a hit Viennese production of La belle Hélène visited the German capital in 1875, the Preußische Zeitung condemned it as “this Jewish speculation on the spirit of modern society [which] caricatures whatever is regarded as sublime and sacred in family life.”Footnote 29 As the Prussian actor Friedrich Haase put it, in the postwar period a Chinese Wall of mutual hostility was erected between French and German culture.Footnote 30

The polarity that Wagner attempted to establish between himself and Offenbach – the principled standard-bearer of a modern, purified ideal of Tonkunst versus the cynical, opportunistic purveyor of meretricious melodies – did not convince the best-informed onlookers. To begin with, there was the striking discrepancy between the nature of their compositions and their domestic arrangements. Eduard Hanslick, who visited Offenbach in 1868, was impressed that his household was staid and middle-class, and the man himself quiet and industrious.Footnote 31 In contrast, Karl Marx, who had shared Wagner’s political ideas in his youth, now wrote to his daughter that the private life of “this New-German-Prussian Imperial musician” seemed apt for comic-opera treatment.

He together with a wife (who had separated from von Bülow), with the cuckold von Bülow, with their common father-in-law Liszt keep house all four together in Bayreuth, hug, kiss and adore each other and let them enjoy each other. Keep in mind as well that Liszt is a Catholic monk and Madame Wagner (Cosima her Christian name) is his “natural” daughter acquired from Madame d’Agoult (Daniel Stern) – one can hardly come up with a better opera libretto for Offenbach than the family group with their patriarchal relations.Footnote 32

Some conservatives preferred to call down “a plague on both your houses.” An anonymous pamphlet that appeared in 1871, Richard Wagner und Jacob Offenbach. Ein Wort im Harnisch [A Word in Wrath], declared that when it comes to harmonic principles they are alike as two eggs. Wagner’s “hatred for musical Jewry is an idle affectation,” an aping of Schumann’s hostility to Mendelssohn; in fact Wagner and Offenbach are “true co-religionists” in their disregard for and mockery of harmony and the rules of taste. If anything, Offenbach goes farther than Wagner in innovative instrumentation, using the bass viol, oboe, and cello to introduce a diabolical element; his are operas for the demi-monde, churning up the scum and filth from the cloacae of Parisian life. The music is composed to express immorality and sensuality. So far the anonymous author echoes Wagner’s diatribes. But if the German public is so debased that it welcomes such vulgarity, it cannot turn to Wagner for a remedy. He is his own Beckmesser, his “unending melodies” bogged down in the elementary lessons of composition manuals.

But in the glorious splendor of a newly risen German empire we want a pure and rational conception at least to prepare a music of the future and opera of the future other than this gross self-over-estimation and the obsolete, unsavoury deviations of the ponderous Wagnerian music of the future!Footnote 33

If Wagner was aware of this attack (and Cosima did assiduously track bad reviews), it must have galled him to be yoked with his bête noire and classified as the greater of the two evils. The anonymous pamphleteer had seen beyond superficial differences to a more elemental similarity: both composers undermined the musical establishment by their innovations. Had he known of the characterization of Offenbach as a “minor Mozart,” Wagner might have baulked at being cast as the little Salieri.

In the face of all this abuse, how had Offenbach responded? He was not a polemicist by nature and, although the occasional private remark has been recorded as hearsay – “Wagner is Berlioz, minus the melody”Footnote 34 – he saved his aggression for rehearsals and litigation over copyright. His ripostes tend to be imbedded in his comedy. As Max Nordau pointed out, Offenbach can be credited with introducing “polemics into the field of music. He is the creator of satirical music … in a struggle against authority and tradition.”Footnote 35 When he was working on La belle Hélène in 1864, he intended to incorporate a parody of the song-contest from Tannhäuser in the second act, but his librettists talked him out of it, replacing it with a game of snakes-and-ladders.Footnote 36

A Pin to Puncture a Balloon

A subtler form of satire is imbedded in Offenbach’s treatment of mythology. The Venusberg setting of Wagner’s first act is meant to display a kind of love that would be later contrasted, to its discredit, with a more spiritual love; the text of 1844/45 refers to Venus’s “sinful desires” and “hellish lust.” His Venus is demonic, a Circean sorceress exploiting voluptuous pleasures to insulate his hero from human feeling and divine salvation. In her grotto (which Wagner originally called “The Mount of Venus,” until he was warned that it would provoke the ribaldry of medical studentsFootnote 37) Tannhäuser is literally enthralled, as if drugged, and, later, when he attempts to describe this sybaritic sojourn, Wolfram retorts “Disgusting fellow! Profane not my ears!” Wagner had been willing to amplify the first-act ballet to offer the Paris audience a simulation of vice in action, but was told that he had to remove it to the second act, since many of the Opéra’s regulars were late-comers, for whom the dancers were the chief attraction.Footnote 38 Wagner’s simulation paled in the face of the actual sexual commerce between the stage and the stalls.

Thirteen years later, Offenbach created the first version of Orphée aux enfers, whose climactic orgy seems to say to Wagner “You called that a bacchanal? This is what a bacchanal should be!” Wagner’s inhibition in portraying unbridled sensuality was also noted by Charles Baudelaire, who, in a review of Lohengrin, complained that, although Wagner loved feudal pomp, enthusiastic crowds and “human electricity,” he “has not represented here the turbulence that in a case like this would be manifested by a plebeian [roturière] mob. Even the apex of his most violent tumult expresses nothing but the delirium of people who are used to the rules of etiquette … Its liveliest intoxication still maintains the rhythm of decency.”Footnote 39

The taunt is even more patent in La belle Hélène. Venus may remain offstage, but she is the motive force of everything that happens, first by coupling Léda and the swan to produce Hélène, next by promising Pâris the most beautiful woman in the world, and then by stimulating Hélène’s libido. The goddess’s machinations go unchallenged by any equal force, and illicit love, indeed adultery, triumphs. This Venus resembles a fairy godmother, bestowing boons and benisons on lovers who belong together. Wagner’s Venus and what she stands for seem frumpy in comparison. If we turn to Tristan und Isolde, which opened during the same season as La belle Hélène, the protracted Liebestod comes across as perverse in its solemnity when set against Pâris and Hélène sailing off into the Aegean sunset. Similarly, seen as a variant of the idiotic cuckold Ménélas, King Marke loses a good deal of his dignity.

Offenbach’s organic reaction to the “grand style” had always been mockery, whether its exponent was Bellini, Meyerbeer, or Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. For him, it was the big lie whose pretensions had to be exposed. And, as Matthew Smith neatly puts it, “Laughter was always the enemy of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the pin that punctured the over-inflated balloon … Of all the exclusions of the Wagnerian stage, laughter is perhaps the most completely barred, and would be the most corrosive if it were admitted.”Footnote 40 Smith’s remark had been foreshadowed by Debussy who wrote in 1903 that Offenbach’s talent for irony enabled him to “make use of the false, puffed-up quality of the music…to discover the hidden element of farce concealed in it and capitalize on it.”Footnote 41 Anyone whose ears ring to the opening strains of the Mount Olympus scene in Orphée aux enfers, with the Greek gods prostrate with boredom, has a hard time keeping a straight face when Wagner’s Nordic deities strut into Valhalla. However, as Debussy pointed out, since the grand style is accepted as high art, attacks on it are misunderstood as coming from a position of inferiority or envy. Offenbach’s ability to elevate comedy to heights of musical inspiration was thus underappreciated.

Nietzsche Takes Up the Challenge

Except by Friedrich Nietzsche. By the time the first Festival strains were heard in Bayreuth, Nietzsche had abjured his early association with and promotion of Wagner. His acquaintance with Offenbach’s work – a Leipzig performance of La belle Hélène in 1867 – predated his first meeting with Wagner; he had planned an essay on the French composer and quotes lines from the comic operas in his letters.Footnote 42 In his mind, Offenbach was identified with Paris, “the highest school of existence,” which he had hoped to visit “to see the cancan.” “As an artist, one has no home in Europe, except Paris,” he would later write in Ecce Homo; and at the very end of his life he was to assert that “For our bodies and our souls … a little poisoning à la parisienne is a wonderful ‘redemption’ – we become ourselves, we stop being horned Germans.”Footnote 43 So when he describes Offenbach as “so marvelously Parisian” he is tendering the highest praise possible.

This early enthusiasm was eclipsed by his pursuit of the German “genius” that Wagner incarnated for Nietzsche at the time of the Franco-Prussian War. He was even willing to dilute his concept of the Dionysian in The birth of tragedy to align it with the cult of Wagner. No more. The “freier Geist,” “the free spirit,” could no longer be contained by Wagnerian formulations: “he who will be free must seek freedom in himself, for no one receives it as a miraculous gift.”Footnote 44 When he attended the Bayreuth Festival performance of the Ring in 1876, he could not conceal his disgust. Hucksterism had eclipsed idealism. Wagner was an impostor, peddling his musical nostrums to a gullible German public, pandering to their spiritual indolence and cultural smugness. Nietzsche became even more alarmed two years later with what he heard from Wagner of the nascent Parsifal and its etiolated Christianity. The completed text, sent to him by the composer, struck him, in its praise of celibacy, as a denial of the life-force. The disillusionment was traumatic.

As he cast round for an antidote to grandiose ideals and messianic aspirations, Nietzsche recovered his taste for “simple foods,” musically embodied by Mozart’s Requiem. His new touchstones were clarity and psychological analysis, qualities he found more readily in French than in German thought. At the same time, he became cognizant of the undeniable popularity of comic opera all over Europe. Throughout the late 1870s and early 1880s, the French opéra comique and Viennese operetta were gaining ground internationally; Gilbert and Sullivan were being pirated throughout the English-speaking world; the Spanish zarzuela flourished. “What is the dominant melody in Europe today, the musical obsession?” Nietzsche asked, and answered himself thus: “An operetta tune (except of course for the deaf and Wagner).”Footnote 45 After promoting Bizet’s Carmen, as part of his call to “méditerraniser la musique,” he nominated his old favorite Offenbach, the puncturer of mendacious megalomania, as the salutary anti-Wagner. His praise of Bizet’s music as light, graceful, stylish, and, above all, loveable, is just as applicable to Offenbach.

To sharpen the contrast, he praised Offenbach as a Jew, since Jews “have touched on the highest form of spirituality in modern Europe: this is brilliant buffoonery.”Footnote 46 Nietzsche’s own anti-Semitism had always been half-hearted, a tribute to Wagner’s influence; it was shed as soon as he had observed its blatant display in Bayreuth. In his notebooks of the 1880s Nietzsche proposed an exemplum of Jewish genius, epitomized in Heine and Offenbach, meant to attack Wagner on his own ground. Offenbach’s “witty and exuberant satire” “is a real redemption from the sentimental and basically degenerate musicians of German Romanticism.”Footnote 47 “Degenerate” or “decadent” [entartete] had been Nietzsche’s catch-all pejorative for weakness and mediocrity; now he used it to mean excess sophistication, the over-refinement of modern life, “hypertrophy of values and subtlety.”Footnote 48 Rebutting those who characterized Offenbach’s music as depraved and meretricious, Nietzsche lauded him as “ingenuous to the point of banality (– he does not wear makeup –),” unlike the cosmetically sensual Viennese school or the crypto-homosexual Wagner.Footnote 49

If one understands genius in an artist to be the highest freedom under the law, divine lightness, frivolity in the most serious things, then Offenbach has far more right to the name “Genius” than Wagner. Wagner is difficult, ponderous; nothing is more alien to him than those moments of high-spirited perfection such as this Harlequin Offenbach achieves five, six times in each of his buffooneries.Footnote 50

Nietzsche’s suspicion that “Musikdrama” discounted Dionysian lyricism for dramatic illustration led him to the conclusion that Wagner’s equalizing of music and drama was wrong-headed: one or the other had to dominate. In Wagner, drama came first, the music composed to fit it; whereas in Offenbach the words were inhabited and heightened by the music. This conviction was affirmed two years later when Nietzsche attended revivals of La Périchole, La fille du tambour-major, and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein.They confirmed his enthusiasm for Offenbach’s classical taste and shrewd choice of librettists. “Offenbach’s libretti have something enchanting about them and are truly the only ones in opera so far that have worked to the benefit of poetry.”Footnote 51 This is another backhanded slap at Wagner, always his own Dichter. Wagner’s self-sufficiency works against him.

Earnest Intensity vs. the Pleasure Principle

Eduard Hanslick had already pointed out that Wagner was the only composer who could be compared to Offenbach as an homme de théâtre, “an eminent theatrical intelligence and brilliant director”; however, unchallenged at his own privately subsidized playhouse, Wagner had lost his sense of proportion and insisted on the immutability of his creations. Offenbach, with a keener sense of theatre and the incalculable benefit of working in collaboration, continually refined his work throughout rehearsals in dialogue with his librettists.Footnote 52 Wagner’s music, errors and all, was graven in stone like the tablets of Mt Sinai; Offenbach’s was fluid, mutable, and open to refinement, sensitive to the responses of the audience. This led Arthur Kahane, Max Reinhardt’s dramaturge, to turn the tables when he declared, in 1922, “‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ is the preferred term in a profoundly programmatic Germany. It has been achieved only [in Offenbach’s compositions].”Footnote 53

For Nietzsche, Wagner was not so much an all-round man of the theatre as a Schauspieler, a ham actor and, indeed, “a mimomaniac.”Footnote 54 In 1888 Nietzsche published The case of Wagner (Der Fall Wagner), a full-throated polemic that again pitted the pleasure principle of Offenbach against Wagner’s earnest intensity. The charge of decadence is deflected from French opéra bouffe to the German composer’s morbid aestheticism, obsessed with the problems of a hysteric and galvanized by the stimulant of mindless brutality. He ventriloquizes Wagner:

Sursoum! Boumboum! […] Virtue is always right, even against counter-point […] We will never allow that music should “serve as relaxation,” that it should “amuse” us, “give us pleasure.” Never do we take pleasure in anything! – we are lost if we start to think of art the way hedonists do […]

Drink up, my friends. Drink the potions of this art! Nowhere will you find a more agreeable way to enervate your spirit, to lose your manhood beneath a rose bush … Oh, this old magician! This Klingsor of Klingsors! How he wars on us free spirits this way! How he to speaks to all the cowardice of the modern psyche, in his siren’s accent! […]

Ah, this old robber. He robs us of our youths, he even robs our women and drags them into his den – Ah, this old Minotaur! The price we have had to pay for him! Every year trains of the most beautiful maidens and youths are led into his labyrinth, so that he may devour them – every year all of Europe intones the words, “off to Crete! off to Crete!”Footnote 55

These passages are craftily interwoven with Offenbachian allusion. Wagner’s anti-hedonist stance is heralded by the braggart General Boum from La Grande-Duchesse and, after a bypath into Klingsor’s garden, we are despatched with the first-act finale of La belle Hélène, not sailing to Cythaera, but to Crete, envisaged as the soul-destroying bull-pen of Bayreuth reached by special excursion trains. Nietzsche was so proud of his pastiche that, boasting of it in a letter, he referred to this exercise in philippic parody as “Operettenmusik.”Footnote 56

Devoted Wagnerians have tried to explain away Nietzsche’s intemperate diatribe by attributing it to the philosopher’s growing dementia. Naming it “that lamentable squib,” Wagner’s Victorian translator William Ashton Ellis stated outright that its author must have been insane.Footnote 57 This belief that Nietzsche’s predilection for light opera was a pathological symptom has been dismissed by Frederick R. Love as a “crude oversimplification,” given Nietzsche’s youthful enthusiasm for the genre and his long-held belief in the spontaneous and voluntary aspect of music.Footnote 58

Nietzsche’s newfound faith in the holiness of laughter and parody as an ideal type of literature would naturally embrace Mozartian virtuosity as a kindred form. When he declares in a letter that “the most strict structural principles and gaiety in music belong together,”Footnote 59 what is more natural than to praise Offenbach as the epitome of this union? Arthur Kahane went so far as to suggest that “Offenbach is a wish-fulfillment dream of Nietzsche’s. Offenbach is Nietzsche set to the fiddle and laughter, or the birth of impudence from the spirit of music.”Footnote 60

Mistaking Sunrise for High Noon

When Nietzsche’s attacks on Wagner appeared, Offenbach was no longer alive; but, had he been, it is unlikely that he would have commented. During his lifetime, Offenbach refrained from public statements about his contemporaries.Footnote 61 His only extended remarks on Wagner appear in an out-of-the-way journal in 1879, the single issue Paris-Murcie, sold to aid those who had lost their homes in the floods of the river Murcie. He began with a disclaimer that, since most musicians have delicate nerves, harsh criticism should be avoided. Still, he wondered if the younger generation might display more talent, were it not

paralyzed by that Medusa’s head that serves as their objective: Richard Wagner. They take this powerful individual as the leader of a school. The methods born with him will die with him. He proceeds from no one, no one will be born of him. A marvelous example of spontaneous generation … An aurora borealis mistaken for the sun.Footnote 62

Where are the progeny spawned by Wagner’s operas which offer influence but not inspiration (a nice distinction)? Musicians have to please their contemporaries, not posterity, Offenbach opines, hence “music of the future” is an oxymoron.

2.3. L’Anti-Wagner, “a Protest against the German Performance [of Lohengrin] at the Eden Theatre,” Paris, 1887. The conductor Lamoureux is shown presenting Wagner with French money.

When Offenbach wrote this, not long before his death, his own fame and popularity were on the wane. In the Third Republic, the unprincipled exuberance of the Second Empire was mistrusted as a prelude to defeat; Garnier’s unfinished Opéra house was so identified with the sins of the past that funding for its completion raised questions in the Chamber of Deputies.Footnote 63 Chastened, sedate audiences required more sentiment, more sententiousness, more spectacle.

Offenbach obliged, his opéras bouffes diversifying into opéras comiques, operettes, féeries, pièces à grand spectacle, even as he was beginning to be eclipsed by younger French composers as well as by the Viennese school of Strauss and von Suppé. Even in his adopted country, his German antagonist was gaining ground. Stéphane Mallarmé worshipped at the altar of “the god Richard Wagner,” dismissing the recent French school as a wilderness overgrown with weeds of Meyerbeerian opera and “decadent” operetta. In Proust’s À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleur (1918), Robert de Saint-Loup despises his father for having “yawned at Wagner and gone crazy over Offenbach.”Footnote 64 Wagner, comfortably ensconced in Bayreuth, secure in wealth and fame, could observe his influence spreading far and wide. Yet, as Cosima’s diary attests, the specter of Offenbach haunted him. When his great rival died in 1880, Wagner could not help but moderate his prejudices. On the principle of de mortuis nil nisi bonum, he repeated his earliest estimation: “Look at Offenbach. He writes like the divine Mozart. It is a fact that the French possess the secret of these things.”Footnote 65 Germans, however, must perforce move in another direction, pursuing their Sonderweg to a different kind of divinity.