One afternoon in November 1829 James Duncan crouched in a canoe in the middle of the Mississippi River. Only a few hours before, Duncan’s purported slave, Vincent, had filed suit against Duncan in the St. Louis circuit court. Vincent alleged trespass, assault and battery, and false imprisonment, technical terms that enabled him to seek something much more elementary – his freedom.Footnote 1

This was not the first time Vincent had used the courts in an attempt to free himself. Earlier that spring, Vincent had instituted his first freedom suit – a legal action in which those held as slaves asserted that they were free people unlawfully held in bondage – against another man, a man he claimed had hired his time.Footnote 2 Because the defendant in this matter could not, in fact, legally claim ownership over him, however, it went nowhere. Vincent eventually had the case discontinued.Footnote 3

When James Duncan learned that Vincent had filed a second freedom suit that named him as the defendant, he was no doubt desperate to frustrate the enslaved man’s efforts. First, Duncan cuffed Vincent and found a man with a dirk to guard him. Apparently under the assumption that he was about to be taken into custody, Duncan then paddled out into the river – convinced, it would seem, that the court’s jurisdiction ended at the water’s edge.

Such was the scene, in any case, when St. Louis county deputy sheriff David Cuyler arrived with an order that barred James Duncan from removing Vincent from St. Louis. Cuyler was attempting to assure Duncan that he did not intend to take him in when a fifth man, Isaac Letcher, who had once hired Vincent to labor at his brickwork, emerged from the brush to enquire whether there would be any “danger” if Duncan returned to shore.Footnote 4 With the repetition of Cuyler’s assurances, Duncan finally relented. Once he reached the riverbank, some portion of this motley crew – Duncan and Vincent at the very least – proceeded to the county courthouse, where Duncan presented Vincent to the judge.

James Duncan and Vincent waged their own particular war against one another in the courts, but in many ways they were typical. In countless encounters in the American Confluence – a vast region where the Ohio, the Mississippi, and the Missouri rivers converge – ordinary individuals, those without formal legal training, repeatedly demonstrated the breadth and depth of their legal knowledge of slavery and slaveholding.Footnote 5 Duncan’s efforts to avoid David Cuyler’s writ may have played as broad comedy, a ham-fisted attempt to ensure he did not wind up in a jail cell. His actions, however, as well as those of all the others who had gathered on the shores of the Mississippi River that day, were based on a sophisticated understanding of the law.

Drawing on a collection of 282 freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court between 1814 and 1860, this book explores how ordinary people absorbed the law, and how the law, in turn, shaped the social and cultural histories of slavery and slaveholding in the American Confluence.Footnote 6 To understand the legal culture constructed by the region’s residents is to understand how the law was used, to imagine not only the purposes to which men like James Duncan, Vincent, or any of the other three men who gathered on the banks of the Mississippi that day thought it could be put, but also the way it constrained and made possible a range of actions, how it might be employed or skirted. Despite distinctions of status and race, those who lived in the American Confluence – masters, slaves, and indentured servants, as well as free black people and their white neighbors – shared a common legal culture, one rooted in knowledge of territorial and state statutes as well as the legal mechanisms that defined the institutions of slavery and slaveholding in the region.

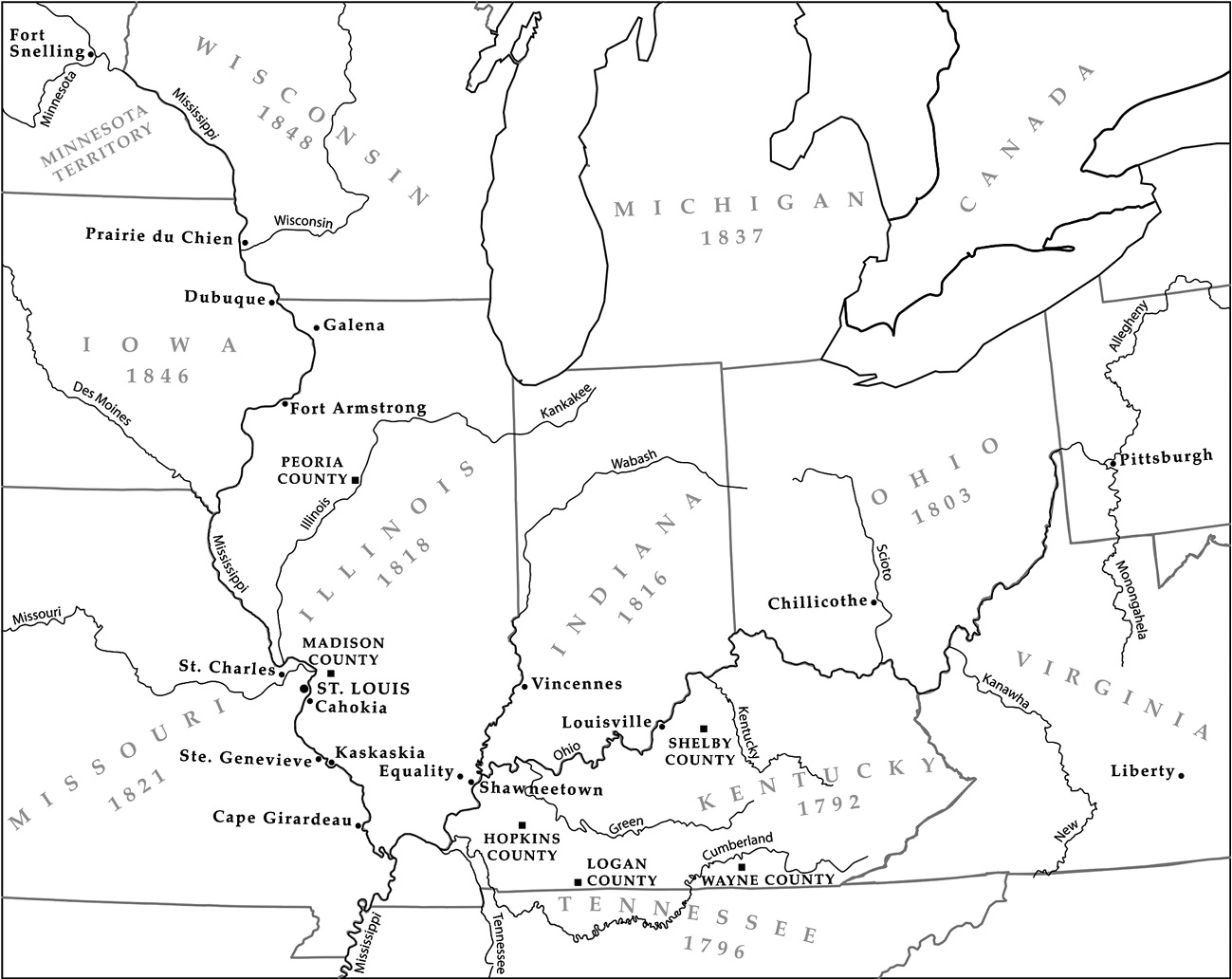

Encompassing portions of present-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri, the American Confluence was part free and part slave. The Northwest Ordinance, adopted in 1787, ensured that the states carved out of the Northwest Territory – the first three of which, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, were admitted in 1803, 1816, and 1818 – prohibited slavery. Kentucky and Missouri, meanwhile, entered the Union as slave states in 1792 and 1821.

While these two competing normative orders met in the American Confluence, the region was nevertheless defined by its fluidity. Although the rivers that traversed it, especially the Ohio River, have often been imagined as borders, the waterways that defined the American Confluence functioned more like corridors. The region may have been carved into slave territories and states and free territories and states, but the border between slavery and freedom was regularly traversed by masters, slaves, and indentured servants, as well as all those they came into contact with.

Map 1. The American Confluence, 1787–1857.

What emerged in the American Confluence, as a result, was a peculiar mixture of slavery and freedom, one that rendered the region part free and part slave in an altogether different sense. Slavery and indentured servitude, after all, were salient features of not only the region’s slave territories and states, but also its free territories and states. Long before the passage of the Northwest Ordinance, many French settlers held slaves in Vincennes, Kaskaskia, and Cahokia; long after the passage of the Ordinance, residents of what would become Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, the latter especially, fought to protect the institution or settled, instead, for a form of indentured servitude that closely resembled slavery. At the same time, opposition to the institution was not only voiced in the region’s free territories and states, but also its slave territories and states. Slaveholders in Kentucky and Missouri occasionally raised concerns about the morality of the institution while their nonslaveholding neighbors, who generally resented the concentration of land and wealth that slaveholding encouraged, often espoused a kind of popular antislavery.Footnote 7

Both slavery and freedom in the region, moreover, were more ambiguous than elsewhere in the United States. There were fewer slaves and slaveholders in the region than there were further south and east, and the advantages slaveholders in other parts of the country enjoyed over their slaves – by virtue of law, custom, or force – frequently broke down. Some masters in the region, in fact, lost perpetual rights of ownership over their slaves when they indentured them. Even when slaveholders held fast to them, however, the American Confluence was a place where slaves might attain an ever-greater degree of autonomy. Many, especially enslaved men but occasionally enslaved women as well, were engaged in occupations that took them out of their masters’ households. Indeed, many slaves in the American Confluence had relatively little contact with their masters since slaveholders commonly rented their slaves’ labor for weeks, months, or even years at a time. Hired out to the region’s lead mines, salines, farms, households, or steamboats, moreover, these men and women sometimes worked alongside free black and white laborers and had the opportunity to earn their own money. Other slaves, those who were not hired out, often lived on intimate terms with their masters. Bound to their slaves by dependence or lust, masters in such circumstances might come to view such slaves more like children and slaves might come to look on masters more like lovers. In such a world, where the boundary between slavery and freedom could be so ambiguous, slaves might be transformed into indentured servants or eventually claim their freedom, but they might just as easily see their privileges stripped away when the whims of a master or the exigencies of the market intervened.

It was no coincidence, in other words, that hundreds of plaintiffs – including Dred Scott, whose case would result in the nation’s most infamous US Supreme Court decision – ultimately petitioned for their freedom in its unofficial capitol, St. Louis. As a bustling frontier town on the very border of a border state, and later, a commercial hub of the West, St. Louis was an obvious site for these battles to take place.Footnote 8 The city’s size and growing importance, after all, drew thousands of new inhabitants every year while its location ensured that a number of slaves who were drawn into its orbit had already spent time on the nominally free soil of the Northwest Territory, an experience that would enable them to prosecute a freedom suit. Its circuit court, moreover, was subject to a variety of emancipatory precedents established by the Missouri Supreme Court over the course of the early national and antebellum eras, and the city itself boasted a large population of attorneys who proved more than willing to represent those who sued for their freedom. The widespread practice of hiring out, meanwhile, common in the American Confluence as a whole but even more prevalent in a city like St. Louis, meant that slaves in the city, like urban slaves elsewhere, had greater autonomy from their masters than their counterparts in the countryside and, therefore, better access to both the judicial system and legal representation.

The proliferation of freedom suits in the St. Louis circuit court, however, was also the result of the legal literacy acquired by the region’s slaves and indentured servants. To some extent, the legal knowledge displayed by such individuals was a product of their status as such. Slaves and indentured servants in the American Confluence, for instance, like others held in bondage throughout the United States, were intimately familiar with the role law played in shaping their lives because, as property, they could be sold, mortgaged, collateralized, or put in trust, any one of which might upend their lives.Footnote 9 But those in the region, far more than unfree laborers in much of the rest of the nation, enjoyed greater opportunities to manipulate the law for their own benefit. They discovered – and employed – statutes that could effect their freedom, obtained competent counsel, and tracked down sympathetic witnesses. They endeavored to keep out of the clutches of their masters’ creditors and, cognizant of the emancipatory power of residence on supposedly free soil, they sought opportunities to travel to or remain in free territories or states, an action that might lay the groundwork for a freedom suit.

Like slaves and indentured servants, the region’s masters as well as its free black and nonslaveholding white residents learned about the law through a combination of their own experiences with unfreedom and the distinctive characteristics of the American Confluence. Masters, after all, were fully cognizant of the economic and social value of their slaves and indentured servants and worked hard to maintain their property in a region where doing so could prove challenging. They learned to buy, sell, bequeath, mortgage, and occasionally indenture their slaves according to legal form. They discovered how long and under what circumstances they could take their slaves to free territories and states without forfeiting ownership. And they became skilled at sheltering their slaves – almost always their most valuable possessions – from seizure by creditors by executing trusts and moving from jurisdiction to jurisdiction to prevent process from being served. Others in the region who regularly interacted with slaves, indentured servants, and their masters, absorbed the laws and precedents that governed both. Such individuals learned the finer points of sojourning, the legally sanctioned practice of taking a slave to a free territory or state, and the significance the courts placed on intent when determining whether a slaveholder had illegally introduced slavery to supposedly free soil by establishing a residence with his slaves. They also dispensed legal advice about how to indenture slaves and occasionally acted as witnesses and deponants when freedom suits arose.Footnote 10

For the last three decades, legal historians, particularly those who have studied the early national and antebellum United States, have increasingly focused their attention on “legalities” rather than “law.” Instead of examining statues, precedents, and formal legal proceedings, in other words, they have concentrated, as one such scholar has noted, on “the symbols, signs, and instantiations of formal law’s classificatory impulse, the outcomes of its specialized practices, the products of its institutions” as well as any “repetitive practice of wide acceptance within a specific locale.”Footnote 11 In doing so, these scholars have made at least two important contributions. First, they have enabled us to answer questions that had previously been opaque or invisible. Without a broader understanding of what constituted law, for instance, historians would not have been able to explain how the people of nineteenth-century New York City famously established a right to keep pigs simply by doing so or how American slaves, who were defined as property could nevertheless own property.Footnote 12 Second, they have dramatically expanded the cast of characters who populate legal history. The field is no longer the sole domain of lawyers and judges. Ordinary people – those who lacked any formal education about the law – have been afforded a primary place in legal history as well.

Legal pluralism, however, has its dangers. Like the Foucauldian understanding of power or the conception of republicanism advanced by J. G. A. Pocock, Gordon Wood, and others, its ubiquity can diminish its explanatory potential: if law is everywhere it is also nowhere; by trying to explain everything it explains nothing.Footnote 13 Additionally, while legal pluralism has permitted early national and antebellum scholars to address not only new lines of inquiry but also a much larger swath of the population, it has, at the same time, generally suggested that ordinary people were locked in a largely antagonistic relationship with formal law. As a result, legal historians have seemingly faced a dilemma: either focus on formal law at the expense of ordinary people, or make ordinary people leading protagonists at the expense of formal law. And they have repeatedly chosen the latter over the former. The balance of much American legal history, in other words, has shifted so fully toward a study of alternative legal culture that, notwithstanding the real benefits of that approach, there is often little room for an examination of how ordinary people engaged, learned, and employed formal law.Footnote 14

The reality, however, is that some historical problems – including an analysis of the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court before Dred Scott – simply cannot be understood without considering how formal law was embraced by ordinary people. To be sure, those who petitioned for their freedom clearly did so for reasons that had little to do with a deep or abiding respect for statute and precedent – they did not, in short, file suit to venerate the law. The very practice of slavery and slaveholding in much of the American Confluence, moreover, was in direct violation of formal law. But one can nonetheless only make sense of their actions and their incredible ability to manipulate the law if one reckons with their detailed knowledge of it. Although their motives sprang from many sources, the tactics and techniques they deployed to secure those ends betrayed a remarkable legal know-how.

The right to petition for one’s freedom in the St. Louis circuit court was a right that was centuries in the making. The ability to do so was ostensibly rooted in a fourteenth-century English law that entitled a serf to seek redress in the king’s courts if he or she alleged illegal detainment.Footnote 15 Thereafter, the right to petition for one’s freedom was imported to England’s North American colonies, where those who filed suit were no longer white serfs but black slaves. The first such cases were filed in the Chesapeake during the middle of the seventeenth century, but plaintiffs subsequently petitioned for their freedom in the Middle-Atlantic and New England as well.Footnote 16

In 1807, shortly after the Louisiana Purchase, enslaved people who resided in the territory west of the Mississippi River were explicitly authorized to initiate freedom suits by territorial statute. “An Act to Enable Persons Held in Slavery to Sue for their Freedom,” like similar laws elsewhere, enabled any slave within the Missouri Territory to petition the general court or any court of common pleas as a pauper. This law suggested that freedom suits might take the form of an action for assault and battery as well as false imprisonment, that is, that the plaintiff in such cases would assert that he or she had been injured by the defendant. It required, moreover, that the matter would be tried like other civil proceedings in which there were two white parties. If a judge found a petition to sue sufficient, the law held that he was responsible for assigning counsel and ensuring that the plaintiff could meet with this court-appointed attorney as needed. This statute also made it illegal for the plaintiff to be either removed from the court’s jurisdiction while the case was pending or “subjected to any severity because of his or her application for freedom,” and permitted judges to require defendants to enter into recognizance if they feared that their orders might be violated. In the event that the defendant refused to do so, the judge was authorized to have the plaintiff taken into custody and hired out until the case could be decided. Finally, according to the statute, if the plaintiff was able to demonstrate – to a judge or a jury – that he or she had been wrongfully enslaved, the court had the power to free not only the plaintiff, but, if the plaintiff was female, any of her children as well.Footnote 17 Revisions to this law shortly after Missouri attained statehood were limited, but, on the whole, rendered freedom suits even more attractive. If the 1824 statute authorizing freedom suits required rather than merely suggested that a would-be plaintiff’s suit would allege trespass in addition to assault and battery and false imprisonment, it also permitted those whose suits were successful to claim damages “as in other cases.”Footnote 18 This law remained unchanged for more than two additional decades, until, in 1845, the state legislature adopted a new statute authorizing freedom suits. Although this law made suing for one’s freedom less appealing by rescinding the ability of plaintiffs in such matters to recover compensation and obligating them to provide a bond that would cover costs in the event that they lost, the right to do so nevertheless remained intact.Footnote 19

As comprehensive as these statutes were in specifying the form freedom suits took and the rights and responsibilities of those who petitioned, however, they were silent on the circumstances that might enable a court to decide that a plaintiff had been improperly held. The acts of 1807 and 1824, for instance, offered no criteria for determining whether or not a plaintiff was entitled to his or her freedom. Missouri’s slave code, moreover, which largely mirrored the one that had been imposed on the whole of the District of Louisiana in 1804, was equally useless: it failed to specify who was and who was not a slave.Footnote 20 As a result, judges were left to figure out for themselves how to interpret such statutes. Without guidance, practice and precedent, rather than legislation, came to dictate the possible reasons a petition for freedom could be filed.

Although, broadly speaking, freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court were based on one of three grounds – prior residence in a free territory or state, previous emancipation, or free birth – neither the lived experience of those who sued for their freedom nor the early national and antebellum case files their efforts produced was ever quite so neat as such categories suggest. Some plaintiffs, after all, could readily claim more than one basis for the freedom suits they initiated. Others, in sometimes-longwinded petitions, might lay out a variety of reasons why they felt themselves entitled to freedom, hoping at least one of them would persuade the court to permit their cause to go forward. In such instances, judges never clarified which claims had convinced them to authorize such suits, nor, in bench trials, did they explain the reasoning behind their rulings. Cases that resulted in jury trials provided somewhat more information, because attorneys jockeyed to have their instructions read to the jurors. But in such instances, as in bench trials, judges provided no justification for any decisions they rendered. Why they accepted one jury instruction while they rejected another must remain a matter of conjecture. All of which is to say that determining a single basis upon which a given plaintiff’s freedom suit was based proves impossible in some instances.

Cases that alleged prior residence in a free territory or state were based on the notion that slaves became entitled to their freedom as a result of an extended stay on free soil – even if they later returned to a jurisdiction where slavery was permitted. This doctrine, known as “once free, always free,” originated in a late-eighteenth-century English freedom suit known as Somerset v. Stewart (1772). In the decades that followed, jurists in several slaveholding states enshrined the principle in American law.Footnote 21 In Missouri, “once free, always free” was first legitimized by a state Supreme Court ruling in Winny v. Whitesides (1824), a freedom suit on appeal from the St. Louis circuit court that was based on the plaintiff’s residence with her master in Illinois. Subsequent rulings on St. Louis freedom suits for much of the early national and antebellum eras signaled not only the court’s commitment to this doctrine, but also its willingness to define residence broadly, which encouraged the proliferation of freedom suits based on such grounds.Footnote 22 Two other decisions, for instance, in Vincent v. Duncan (1830) and Ralph v. Duncan (1833), established that hiring one’s slaves to labor in the Northwest Territory, or any state carved out of it, likewise effected their emancipation.Footnote 23 In rulings on two more St. Louis freedom suits, meanwhile, Julia v. McKinney (1836) and Wilson v. Melvin (1837), the court asserted that even an unnecessary delay while transporting slaves across free soil would effect their freedom.Footnote 24 Finally, in Rachel v. Walker (1836), yet another St. Louis freedom suit, the court held that a slaveholder’s compulsory service at a military post in the Northwest Territory did not insulate his slave from the emancipatory laws therein.Footnote 25 Such precedents remained intact until the middle of the 1840s, when the court began chipping away at the notion that the Northwest Ordinance had the power to free every slave who resided there, however briefly.Footnote 26

The idea that a slave who had been previously emancipated was entitled to his or her freedom – the second grounds upon which freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court were based – was comparatively straightforward from a legal standpoint. The vast majority of such petitioners claimed that they had been emancipated either by will or by deed, but a number of other circumstances might have led one to claim prior manumission as well. Some argued that they had contracted with their masters to purchase their freedom and had already paid some or all of the agreed-upon price without being liberated. Others asserted that they were entitled to their freedom because they had been sold under the condition that they would be freed at a specified time that had come and gone. Still more argued that, as indentured servants whose terms had ended, they could no longer be legally held to service. Finally, a handful claimed that they had already won a freedom suit in another jurisdiction or that their enslavement had legally ended when they were imported into a slaveholding state that had banned the introduction of additional slaves for the purpose of sale.Footnote 27 In contrast to residence on free soil, prior manumission entitled a plaintiff to his or her freedom on its face. Those who based their cases on such claims, after all, were, by definition, free people. As a result, to the extent that freedom suits that revolved around previous emancipation were appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, the only questions they posed were related to the legitimacy of the various instruments that had supposedly freed them. At issue, in other words, was whether a particular will, contract, or bill of sale had been created according to law. Because such decisions could only be narrowly applied, they did little to expand – or contract – the parameters of prior manumission over the course of the early national and antebellum eras.Footnote 28

The notion that one was entitled to freedom because he or she was born free, which constituted the third basis for St. Louis freedom suits, appeared to be a similarly uncontroversial legal claim. Occasionally these petitioners explicitly asserted that they had lived as free people, whether in free territories and states or slave territories and states, before they were kidnapped or decoyed into slavery. Others merely mentioned that they were born in free states or territories without ever explicitly asserting that, as such, they were born free. Still more acknowledged that they had been held as slaves all their lives, but argued that because their mothers had either become free or been entitled to freedom by the time they were born, they were entitled to freedom as well. In doing so, such plaintiffs relied, implicitly at least, on the legal principle of partus sequitur ventrem, which specified that anyone born to a free woman was also free.Footnote 29 Those who asserted that they were born free, in fact, often filed simultaneously or jointly with their mothers, whose own freedom suits were prosecuted on the basis of residence on free soil or previous emancipation. If proven, the claim that one was born free, like the claim that one was previously emancipated, necessarily demonstrated the illegitimacy of a plaintiff’s enslavement. As a result, the right to petition for one’s freedom on the basis of free birth was never at issue before the Missouri Supreme Court. The question of whether or not the petitioners’ mothers were entitled to freedom by the time the petitioners were born, however, was occasionally raised. Generally speaking, such cases resembled those based on residence in a free territory or state or prior manumission, with one notable exception.Footnote 30 In Marguerite v. Chouteau (1828), a St. Louis freedom suit filed by a woman whose ancestors included a Natchez Indian woman who had resided in Spanish territory where Native American slavery had been banned, the court established that slaves who could demonstrate such descent had a right to their freedom.Footnote 31 Because few slaves in the region were direct descendants of Native Americans, and even fewer could prove it, however, the precedent established in Marguerite v. Chouteau was rarely employed by those who filed suit in St. Louis.Footnote 32

Such grounds were not mobilized equally. All told, 241 plaintiffs petitioned in the city.Footnote 33 Of those, at least 137 claimed that they had previously lived on free soil, a testament to the mobility that was endemic to the region. The second most common grounds provided for a freedom suit filed in the city was free birth, which was claimed by no fewer than 71 plaintiffs. Finally, at least 61 plaintiffs filed petitions in the St. Louis circuit court that referenced previous emancipation.Footnote 34

No matter what the basis of one’s suit, success was not assured. Of the 241 plaintiffs who sued for their freedom in the St. Louis circuit court, 97, or 40.2 percent, ultimately won their freedom. Another 112, however, or 46.5 percent were not freed by the St. Louis circuit court. The fate of 32 additional plaintiffs, or 13.3 percent, moreover, is unknown.Footnote 35 That said, there were some circumstances that increased the likelihood that a plaintiff would be successful. Those who claimed that they were born free, for instance, won significantly more often than those whose cases were based on either prior residence on free soil or previous emancipation. Occasionally, moreover, plaintiffs might be willing to appeal the circuit court’s decision or file additional petitions, and their persistence, it seems, bettered their odds, if only slightly. Filing two, three, or, in one instance, four successive freedom suits increased one’s chance of success: 46.6 percent of the 45 plaintiffs who filed on multiple occasions were eventually freed.

In addition to confronting the very real possibility of defeat, those who sued for their freedom also faced a number of hurdles in bringing their cases to trial. First, despite the fact that they were permitted to sue as paupers and provided with representation by the court, evidence suggests that they often sought out their own attorneys and paid for such services with their own money. How much they may have spent prosecuting their suits remains elusive, but these fees no doubt represented a burden.Footnote 36 Second, they exposed themselves – and their families – to a variety of dangers. To prevent the prosecution of a freedom suit, a defendant might sell, or otherwise remove the plaintiff from the court’s jurisdiction, despite being instructed not to so. Others might subject those they claimed to beatings either out of anger or in an effort to intimidate them from pressing their claims any further. Still more defendants might try to prevent plaintiffs from meeting with their attorneys. To prevent these abuses, the court ordered defendants to post bond if they wished to maintain possession of those who filed suit against them. But such measures were not always successful. Because some defendants proved unable or unwilling to provide the security that would enable plaintiffs to remain in their custody, moreover, some plaintiffs were either hired out at the court’s convenience, which occasionally meant working for an abusive master under unpleasant conditions, or kept in the county jail, in an environment that often posed a threat to their health.Footnote 37 These risks were not undertaken by the plaintiffs alone. A freedom suit might also endanger a plaintiff’s loved ones. If a plaintiff was removed from the court’s jurisdiction, for instance, his or her children would be left without a parent. Those who managed to remain in the city to prosecute their cases, meanwhile, potentially exposed family members to a variety of reprisals if the defendant laid claim to them as well.

The importance plaintiffs placed on their family and friends is plain in such cases. Many of those who sued for their freedom in the St. Louis circuit court filed alongside those they knew well. Others did so after someone within their kin network had already obtained a favorable decision. Women, their children, and grandchildren, formed a significant proportion of plaintiffs: nearly 30 percent of those who sued for their freedom in the St. Louis circuit court were part of one of these matrilineal groups. In other instances, siblings filed without their mothers. But there were others who sued with their loved ones as well. In addition to Dred and Harriet Scott, two other enslaved couples, Laban and Tempe and John and Suzette Merry, petitioned together.Footnote 38 On still more occasions, those who shared the same master petitioned for their freedom in concert with one another.Footnote 39

The likelihood that one’s efforts would end in disappointment, or worse, and the challenges and risks they encountered, help explain, in part, another distinctive feature of such cases: those who sued for their freedom often delayed doing so. Although plaintiffs whose cases were based on any of the three grounds often spent months or years in St. Louis before they filed suit, those who alleged residence in a free territory or state are, perhaps, especially illustrative. These plaintiffs waited a significant period of time, often several years, after they reached the city to initiate a case.Footnote 40 Such evidence suggests that the decision to pursue a freedom suit did not represent an irrational devotion to a legal system that otherwise ignored or failed them or a commitment to freedom at any cost. It was, instead, a calculated venture, an assessment rendered after carefully weighing all the potential costs.

The scope and breadth of the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court varies tremendously. There were no trial transcripts taken in such cases, but a handful of the case files span more than a hundred pages, complete with perhaps a dozen detailed statements from various witnesses in the form of depositions or affidavits. Others include no more than a single page, often just a plaintiff’s petition, which provided legal justification for a suit and occasionally a rudimentary biography, or perhaps a declaration, a pro forma document filed by the plaintiff’s attorney that spelled out the charges he or she was leveling at the defendant. In addition to the occasional deposition or affidavit and the ubiquitous petitions and declarations, case files might contain evidence offered to the court in the form of bills of sale or baptismal records, as well as lists of potential jurors, jury instructions, appeals, and bills of exceptions, which detailed a judge’s decisions for the purpose of bringing them under the review of a superior court. Much of the documentation, however, consists of far more mundane legal records: pleas and replications, which resembled declarations in their numbing similitude, dedimuses, which compelled far-flung justices of the peace to take depositions, and, most of all, summonses, which called potential witnesses to appear in court.

Such documents present unique challenges. First, they often provide a maddeningly spotty narrative. Clerks, whose legal training and literacy varied wildly, often recorded information only as they saw fit or took down depositions only after they had been completed. While a brief account of a witness’s testimony might be included in an appeal, moreover, transcriptions were unheard of in civil suits. As a result, in the vast majority of cases, one might know who testified, but not what his or her testimony contained. Complicating matters even further, many cases describe episodes that had taken place months – if not years – before, long after memories had been altered, not only by the passage of time but also by subsequent events. Finally, these inconsistencies are compounded by the explicit biases built into legal documents. Attorneys filed petitions that included partial – and often partisan – information. The adversarial process, the hallmark of western law, ensured that there were almost always two plausible versions of events.

Because they were geared for the legal process, case files can be notoriously difficult to interpret. As one might expect, the material left by the lawyers, judges, and witnesses in these freedom suits tell a distinctly legal story. They provide a valuable – and unique – glipse of those who populated these cases from the diverse vantage points of the proceedings’ many participants, but they also provide information that was shaped for the legal process, designed to protect the interests of those who filed suits and those who defended them. Additionally, such documents were never unmediated. Even those that bear a plaintiff’s mark or supposedly contain the sworn statement of a witness were prepared by a third party. They provide, at best, an imperfect window into the consciousness of those under examination. And what they do not tell is often essential: focused as they are on evidentiary claims, they often provide little insight into participants’ thoughts or feelings. Finally, case files tend to obscure and omit the very information necessary to explain how the law operated. As one scholar has suggested, even well-documented cases relied on a “universe of unstated assumptions, the kind of everyday knowledge that was so deeply embedded in people’s lives that it no longer needed to be articulated.”Footnote 41 In short, the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court, much like legal documents elsewhere, do not always yield their insights willingly.

In order to overcome these challenges, I have read the case files of the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court judiciously. Although I have not followed one scholar’s admonition to “read the docket record as if it contains only lies,” neither have I presumed that such documents provide access to some kind of unvarnished truth.Footnote 42 While any historical narrative requires the historian to make choices about whose words and which interpretations he or she will privilege, moreover, I have endeavored to signal to readers where sources disagree and explain the range of possible meanings one could assign to any given source. Finally, where possible, I have attempted to corroborate the information presented in case files using wills, census rolls, newspapers, local and genealogical histories, court cases from other jurisdictions, and probate records.

Additionally, instead of offering a comprehensive overview of the St. Louis freedom suits, I have attempted, where possible, to reconstruct the full human experiences and logics case files otherwise embody. Doing so has meant focusing in depth on a series of cases, reconstructing entire stories with an eye towards glimpsing the deeper truths a case can reveal. An aggregate treatment has its virtues, but it cannot fully grasp the calculations that brought those who sued for their freedom and their defendants to court. Nor, more broadly, can it plumb the deeper moral depths of slavery. I have, thus, adopted a microhistorical approach in the belief that only such granular treatments of individual cases can reveal the broader significance and meaning of the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court.

To be sure, neither the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court nor the plaintiffs who filed them were representative in the traditional sense of the word. Because there were few circumstances in which slaves could directly participate in the law and slaves were excluded from the vast majority of formal legal proceedings, freedom suits do not resemble any other area of slave law. The number of plaintiffs who prosecuted freedom suits in the city, moreover, as large as it is, constituted only a fraction of the slave population in the American Confluence as a whole. Acknowledging as much makes plain the obvious: most slaves in the region did not sue for their freedom.

Such cases, however, stand in for a silent body of freedom suits that remains just offstage – cases that have not survived or were not filed in the first place. Some cases, after all, have been destroyed or lost.Footnote 43 Others were never formally instituted. The individuals who might have initiated such suits may have been prevented or deterred from doing so for a variety of reasons. Some were denied access to an attorney or the courts by their masters, who either removed them from a particular jurisdiction, sold them, or simply kept them from the region’s towns and cities, like St. Louis, where sympathetic lawyers, witnesses, and others might be found. Others were freed, either de facto or de jure, before they filed suit – perhaps, in some instances, as a result of their threats to do so. Regardless, the extant freedom suits, though few in number when compared to the region’s enslaved population, reflect the experiences of a much larger portion of the population.

As such, the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court provide a new opportunity to hear the voices of those held in bondage, but they must be read with care. Those voices make plain that such individuals, when given the opportunity, made savvy use of the law. But they also reveal that they did so, to the extent possible, to serve their own purposes. While the legal proceedings they initiated may be referred to as “freedom suits,” the term itself is perhaps misleading. What exactly plaintiffs sought when they filed suit, in many instances, is difficult to piece together, but their actions make plain that, at best, freedom was only one of the goals they pursued by doing so. The notion that they necessarily “turned to the courts for justice” or that, in suing for their freedom they “put their faith” in the legal system or “sought an objective that is universal and transcendently human” is not borne out by the available evidence.Footnote 44 Historians in many other subfields long ago discarded such transhistorical sublime motives or rationales in favor of a “thick description” of the fine-grained contexts in which those motives or rationales were deployed.Footnote 45 Because of the presentist moral shadow cast over the study of slavery, however, all too often the motives and rationales of the enslaved are assumed to conform with modern norms. The attempt to “return” agency to slaves has paradoxically led some scholars to assume, in the absence of evidence, that slaves were modern, liberal individuals, with motives and rationales identical to our own. But substituting our own worldview for theirs is much less “empowering” than reconstructing their unfamiliar motives and rationales on their own terms.Footnote 46

The freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court also reveal a coherent region in the heart of the continent that has been rendered largely invisible by the assumption that the borders between slavery and freedom were always as meaningful and explicit as they became on the eve of the Civil War. They likewise demonstrate the detailed knowledge of often-contradictory statutes the region’s residents developed as they moved from territory to territory and state to state. Together, mobility and political geography made the American Confluence a natural site for the proliferation and dissemination of information about the law, especially perhaps, the law of slavery and slaveholding. Bonded laborers, in turn, who learned about the law through their own journeys across the region and the experiences of all those they came into contact with, subsequently used the legal literacy they acquired to sue for their freedom.

Finally, in addition to shedding light on the region and its peculiarities, these cases can also capture foundational social practices in early national and antebellum America more broadly. The stories revealed in the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court, after all, never only pertained to that court, that city, or the region of which it was a part. These cases, in fact, often featured participants who had come from far beyond the American Confluence itself. In a sense, because many freedom suits feature average Americans chasing one another from the east coast to the Mississippi River, they literally took place all over the country. Even more crucially, the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court reveal how foundational social practices that include mobility and debt converged. In the decades between the adoption of the Northwest Ordinance and the US Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott, the worlds of slavery and freedom, law and society, west and east, north and south, were inextricably intertwined in a single lived experience, an experience these cases show, quite unlike any other sources from the period.

This book is divided into two parts. Part I provides the context for and explores the lessons from the freedom suits filed in the St. Louis circuit court. Chapter 1 examines how the region’s ambivalent relationship to slavery and freedom rendered the status of the black workers in the American Confluence ambiguous. The second chapter explores how slaves and indentured servants educated themselves about the law, with particular emphasis on the construction of legal knowledge within a dense, tangled network of those who inhabited the region, whether they were free, enslaved, or indentured. Chapter 3 examines the attorneys who agreed to represent those who sued for their freedom in the St. Louis circuit court, the quality of representation they provided, and the ideological commitments that motivated their work on behalf of freedom suit plaintiffs. Part II draws on the tools of legal anthropology to provide literal case studies that reveal the personal – as well as the legal – consequences of slavery and slaveholding in the American Confluence. The fourth chapter reconstructs one plaintiff’s journey across much of the American Confluence to show how the law shaped the lives of small slaveholders and their interactions with their slaves and how slavery fostered the development of a sophisticated understanding of property and debt among ordinary people. Chapter 5 traces another plaintiff’s efforts to establish de facto and de jure freedom, by both calling his masters’ performance of mastery into question and exploiting the precarious nature of slavery and slaveholding in the American Confluence. The sixth chapter explores how one slaveholder deftly manipulated the region’s multiple jurisdictions in an attempt to evade and frustrate the creditors who laid claim to his slaves. Chapter 7, the final case study, explores what Lucy Delaney’s slave narrative and her mother’s case file can reveal about how residents of the American Confluence made sense of their own experiences with slavery and freedom in the region and explores the subjectivity of their memories. Finally, the conclusion shows how Scott v. Sandford (1857) signaled the demise of the region’s distinctive legal culture, a legal culture that produced one of the largest collections of freedom suits in the United States.

Situated on the border of slavery and freedom, ordinary people in the American Confluence – masters, slaves, indentured servants, free blacks, and their white neighbors – became expert at navigating the law. Essential to the formation and maintenance of slavery and slaveholding in a liminal region, legal knowledge became common currency. Although ordinary people routinely brought informal and extra-legal concerns to bear as they prosecuted, defended, and participated in the proliferation of freedom suits, this book reveals that the region’s early national and antebellum legal culture was based on a sophisticated understanding of formal law and the ways it might be pragmatically employed to advance individual, and often divergent, interests.