In Europe in the mid-1930s, a selective memory of the imperial past shaped new mass ideologies as well as the ideas of much smaller social groups. Many Europeans, one could say, not only suffered the ‘phantom pains’ of imperial decline. They also tried to reassemble elements of knowledge from the historical past of Europe to build up the faces of future empires. In the final two chapters, I reconstruct how the ideas of the mostly liberal fraction of the European elites, which I discussed earlier in this book, related to both trends.

Chapter 6 focuses on the emergence of a racial memory of empire. Looking at the rise of Nazi ideology through the lens of social history foregrounds the importance of common forms of imperial memory, which facilitated the social recognition of newcomers such as Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg. Rome is introduced as the capital of a transnational neo-imperial sensibility, and Munich is a site where the ideologues of National Socialism first gained prominence. The chapter is concerned with the question of how elements of aristocratic identity, such as the idea of pedigree, became absorbed in Nazi ideology.

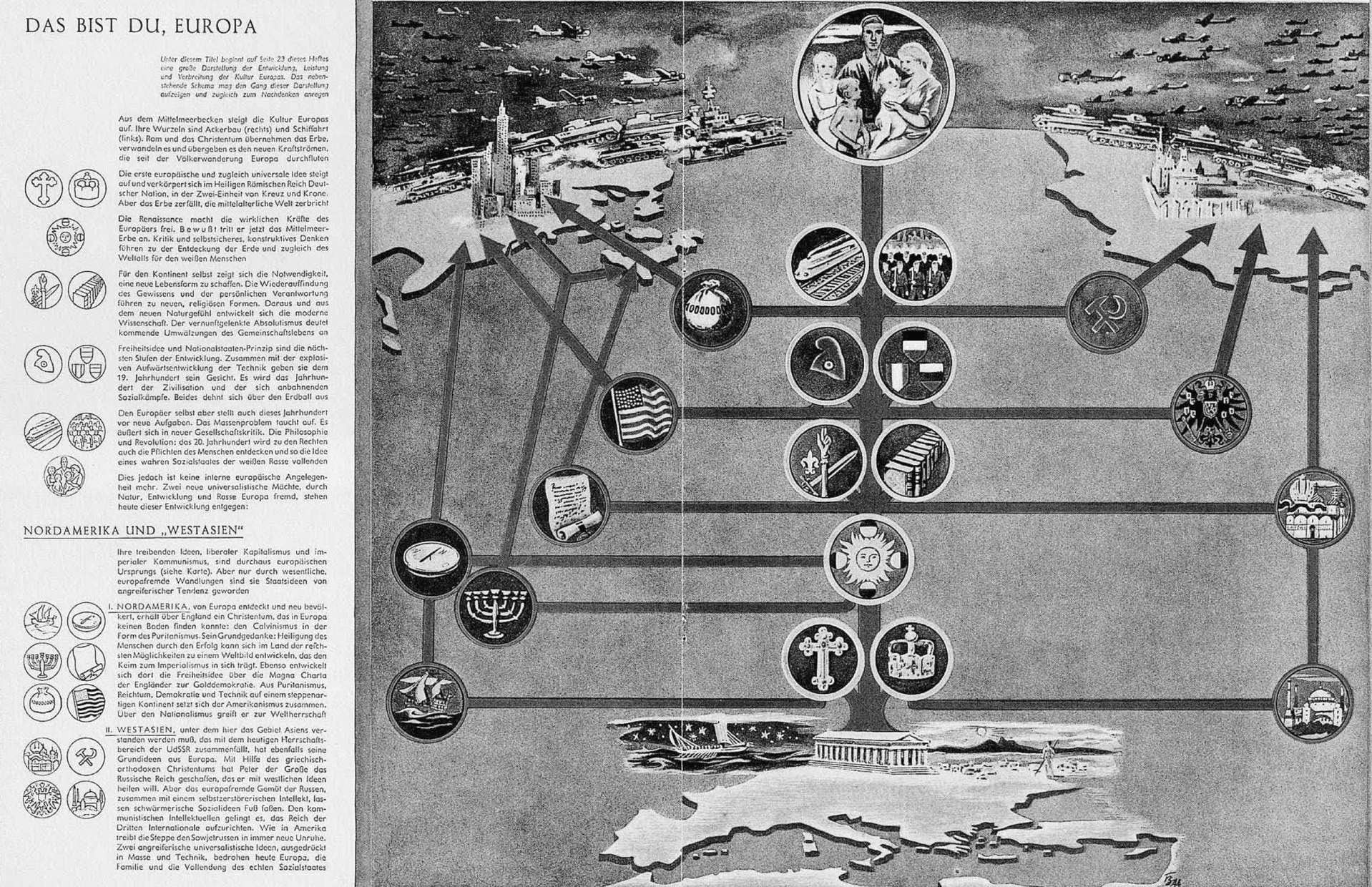

In 1944, the Nazi propaganda journal Signal produced a mental map of Europe [Fig. 24]. On this map, we can see an abstract genealogical tree superimposed over a map of Europe. Its central lineage leads from ancient Greece to a generic Aryan European family in the present. Two side lineages, with notable influences from Jewish culture and Orthodoxy, point to the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively. In reconstructing the social relationships between the Nazis and the representatives of the old Germanic nobility in the 1930s, I want to establish the difference between the racial and the familial use of pedigree in Nazi ideology and in the genealogical practice of Habsburg and Baltic nobility.Footnote 1

Figure 24 ‘Map of Europe’s Cultural and Historical Development’, in M. Clauss (ed.) Signal, 11, 1944. From Facsimile Querschnitte durch Zeitungen und Zeitschriften, 14 (Munich, Bern, Vienna: Scherz, 1969)

Chapter 7 looks at a very different nostalgia for empire, which was characteristic of a small transnational elite community whose cultural centres were Paris and London. At the centre of this configuration was the Bloomsbury group. Its members associated imperial sensibility with a kind of multiculturalism, which they believed was threatened not only by the rise of fascism but also by narrow-minded nationalism elsewhere in Europe. In the chapter, I hope to recover the extent to which some of the German cosmopolitans discussed earlier in the book had influenced the nature of imperial memory in these circles.

When, in November 1918, Alfred Voldemarovich Rosenberg, subject of the Russian Empire, returned to his hometown of Reval after two years in Moscow and in Crimea, the only thing that had remained unchanged was the city’s architecture. The name of the city was now not Reval, but Tallinn; the state it was in was no longer the Russian Empire, but Estonia. Alfred Rosenberg was the subject of a non-existent empire. His plan to join the administration of the German army occupying Livonia, or the land ‘Ober-Ost’, as they called it, was futile: after the collapse of the German Empire, the German army, which had been victorious against the Russian Empire from the start of the war, was beginning to withdraw.Footnote 1 In twenty-two German states, new governments had just proclaimed a republican order, and all questions of citizenship were suspended, so that Rosenberg could not hope to obtain the citizenship of any other country either.

Rosenberg’s political career began at this moment with a public speech hosted by his student fraternity in Reval about the Jewish conspiracy in the Russian revolution. It ended twenty-seven years later, with death by hanging at Nuremberg’s Court for Human Rights. The scale of civilian destruction under the regime to which his ideas provided legitimacy was so unprecedented that he and the core of his fellow party members were tried under an altogether new criminal code: ‘crimes against humanity’. Rosenberg, an engineer by training and historian of Europe by vocation, had contributed to a system of thought, which the international legal community deemed planetary in terms of its scale of destruction to human lives and to existing legal norms of more than one nation.

One of the questions that historians have been asking themselves ever since is this: How was it possible that a political regime accorded to itself such a degree of licence in breaking norms of national and international law? Imperial decline was, if not a cause, certainly the necessary circumstance behind this radicalization, which occurred when the imperial city states lost their special status. In this period, ideas of ‘special’ legislative frameworks, which were opposed to the principles of equality, gained new attraction. During the Great War, the Middle Ages had become fashionable among an entire generation of disoriented Europeans. The special role of cavalry on the eastern front was one of the triggers for this return to the classic ideal of the knight. In the Baltic region, chivalric dreams had particular appeal among the educated middle classes, whose representatives identified with different parties in medieval struggles between Livonian Knights and Lithuanian Dukes, Teutonic Knights and Russian Princes, which went on from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. As we have seen in the chapter on the Baltic Barons, the chivalric model of exclusivity associated with such organizations as the Teutonic Knights still persisted, as the knightly orders continued to exist until the 1930s. At the same time, the cities developed their own cult of identity, with merchant guilds rivalling the exclusivity of old Crusaders’ lineages and competing with them for favours of the current ruling imperial dynasties.

During the last years of the Great War, Rosenberg had been a student at Riga’s Polytechnic School, which had been evacuated to Moscow while the German army occupied Livonia. He spent the winter of 1916 and 1917 in a suburb of Moscow, reading Chamberlain, Balzac, and Dostoyevsky. Never enlisting in the army, Rosenberg nonetheless witnessed the Russian Civil War in Moscow and also in Crimea. Here, another Baltic German, Baron Wrangel, a general who had distinguished himself on Russia’s Galician front against the Austrians, formed a resistance army against the Bolsheviks, the nucleus of what is now known as the ‘white army’.Footnote 2

In this time of uncertainty, Rosenberg’s most stable affiliation was not with a state organization but with his university fraternity, Rubonia. The fraternities at the universities of Reval, Dorpat, and Riga were now all based in different states, and the communities that made them up aspired to different citizenships, but individual memberships had remained intact. In 1918, Rubonia was to be his first and last point of call before he would begin a new life in Germany. Less than ten years later, Rosenberg became the co-founder of a new Germanic order that would fulfil the dreams of the German crusaders that had been crushed at the battle of Tannenberg of 1214. In 1934, 700 years after the Livonian order had been defeated at Tannenberg and twenty years after the imperial German army under Hindenburg defeated the Russians at the same place, he and fellow members of the National Socialist party gathered at Marienburg near Gdansk to consolidate their commitment to a new German Empire under the leadership of a new Teutonic Order.Footnote 3 In Germany, in 1934, Rosenberg wrote admiringly how in the Middle Ages, ‘knights were departing Germany into the wider world again and again in pursuit of their phantasy of a world empire and the conquest of Jerusalem’.Footnote 4 The motion that began during the Russian Civil War propelled Rosenberg from his intended career as a civic engineer in one of the minor, yet culturally advanced cities of the Russian Empire into the core of a political movement that for a few years would control a territory reaching from the Crimea in the south to the Baltic in the north, from Moscow in the east to Normandy in the west. It was, in other words, a journey from empire to empire.

Twenty years after his departure from Reval, Rosenberg became one of the chief ideologues of the Nazi party, which meant having one of the largest budgets for culture at his disposal available to a government minister of his generation. The Nazi project was a new ‘Order State’, led by a small circle of vanguard representatives devoted to a charismatic leader like the Teutonic Knights were to their grand master. Men like Rosenberg, as well as Heinrich Himmler, Martin Bormann, Josef Goebbels, and others, saw themselves as the new knights, whose shared fidelity to their leader, they believed, could outshine their mutual rivalries. They held smaller conventions in historic locations such as the ruined castle of the Livonian Knights, Marienburg Castle, when it was still in Polish hands, and in Weimar, while its recently deposed princely family was still present. These revived Teutonic Knights had recourse to the highest technologies of modern mediation. Deliberately opposing the idea of a secret order, which they associated with Freemasonry and the Jesuits, their ideas and the meaning they attached to their flag, a swastika, would soon reach the widest possible public thanks to radio and sound film.

The scope of his cultural activities reached from the smallest German town to the newly occupied territories of western, southern, and eastern Europe. The department named after him would be responsible for the collection and public presentation of information on Germanic heritage and that of its enemies. He was one of the organizers of the Degenerate Art and music exhibitions in Munich and Düsseldorf, alongside major historical exhibitions on European history. Under his auspices, the Nazi party sponsored local and folk culture as well. After the occupation of Paris and parts of France, Rosenberg’s team organized the spoliation of artworks and archives, chiefly belonging to Jewish families who were resident or had moved to Paris. A second strand of Rosenberg’s career started with the expansion towards the east, when, in 1943, Rosenberg became Minister for the Eastern Territories. He saw his life project as a restoration of the project began by the Teutonic Knights in the Middle Ages until their crushing defeat by a Polish army of 1415. The period from 1415 to 1914, in his view, was a dark time for Germanic culture, whose true home was in the Nordic Middle Ages. But the German victory against Russia at the Battle of Tannenberg in 1914 – the main victory in a war Germany had lost – began to ‘right’ the historical wrongs that Rosenberg identified with the entire period of European history that was associated with republicanism and the emergence of eastern Europe’s small states.

The new Nazi Order was an attempt to revive a new Middle Ages against what the Nazis considered the subversion of this tradition: the Enlightenment associations they associated with the Freemasons, for instance, with their lofty ideas of human rights.Footnote 5 By 1945, of the inner circle of Nazi ‘knights’, about one-third would be killed by internal agreement for failing to live up to the ideal, and one-third would commit suicide. The closest to Rosenberg’s heritage movement, Baron Kurt von Behr, would die from a mixture of champagne and cyanide at Castle Banz, one of the bastions of looted art. The remaining third – including Rosenberg himself – would die by hanging for a new kind of crime: crimes against humanity. The language in which the new legislation was formulated, in a desperate attempt to match the scale of human destruction masterminded by the Nazi movement, hearkened back to the French Revolution and those ideals of humanity which Rosenberg himself most deeply despised.

In some ways Rosenberg’s ideas were not extraordinary but typical of his time, and particularly, his place of origin. In his memoirs, Rosenberg outlines the path of a middling sort of person, thrown out of his orbit by radical social and geopolitical changes of his time.Footnote 6 This should not be interpreted as saying that the sort of ‘evil’ to which his regime contributed was necessarily banal, as Hannah Arendt said of the lower functionaries of the Holocaust machine. Rather, what was common was the ideological make-up that these actions received. Given the fact that life in interwar eastern Europe is largely familiar to us today through the pens of Holocaust survivors or émigrés from the Baltic region occupied by the Soviet Union, it is almost shocking to see the extent to which Rosenberg’s impressions of life in a Baltic city in the 1900s and 1910s echo the way these other representatives of the urban middle classes, not only of German but also of Russian, Jewish as well as of Lithuanian heritage, saw their cities.Footnote 7

Beyond the confines of this region of eastern Europe, the new interest in ‘barbarism’, imagined as the opposite of feeble, civilizing spirit of the French and the Norman, was attractive to a whole generation of new Europeans. The Russian fascination with its Scythian past, the British fascination with Celtic heritage, and the emergence of neo-masculine movements such as the Boy Scouts all form part of the same tradition. Moreover, the Baltic rediscovery of its medieval heritage was closely entangled with the neo-medievalism of British and Russian intellectuals. Lithuania had one of the earliest chapters of the World Scouting organization started in Britain by Baden-Powell, and also founded on a chivalric ideal.Footnote 8 In 1932, Baden-Powell even travelled there to receive the Order of the Grand Duke Gediminas of Lithuania for his 75th birthday from the president of the short-lived republic. The honour codes of neo-chivalric youth associations like the Scouts were the predecessors not only of the SS, or Schutzstaffel, but also of the Soviet Comsomol, as well as some dissident organizations fighting against the Nazi and the Soviet regimes and maintaining identities in exile.Footnote 9

Nearly a decade before the infamous Stalinist purges reached their apogee in 1937, it was Feliks Dzerzhinsky, a native of this region, who set in motion that machinery of purging the revolution from its internal enemies that had guaranteed him lasting fame in Soviet commemoration and the nickname ‘Knight of the Revolution’ from his successors.Footnote 10 Dzerzhinsky’s brainchild was an organization called the ‘VChK’, or ‘All-Russian Emergency Committee’, a unit that combined intelligence and military work in identifying counter-revolutionary elements from within the ranks of the Bolshevik party as well as across Soviet society. Its symbol was an emblem: a sword crossed on a shield, covered by another emblem, the newly established hammer and sickle, as symbols of the worker and peasant. This double emblem was minted and given for the first time as a decoration of honours in 1922, the fifth anniversary of the VChK.Footnote 11

People of their circle had grown up reading Walter Scott’s adventures in the Scottish highlands. In the Russian Empire, the first translations had appeared as early as 1828 and were a common presence in a classical eighteenth-century estate library.Footnote 12 They later also became supplements to the popular journal Vokrug sveta [Around the World, an imitation of the Parisian Revue du Monde]. Closer to home, an important narrative was the story of the despicable behaviour of Russian imperialists during the uprisings of the mid-nineteenth century, chiefly embodied by Count ‘Muraviov, the hangman’. This illegitimate form of hegemony was personified by the Russian governor general of Vilna, Nikolai Muraviev, who hanged over a hundred people and deported nearly a thousand to Siberia during the so-called Polish Uprising of 1863. An album, published in Polish in the Habsburg-controlled city of Lemberg on the eve of the First World War, commemorated the event in pictures.Footnote 13

Emigrés and victims of the Cheka highlighted his ruthlessness.Footnote 14 There was, they all agreed, a logical necessity to figures such as Dzerzhinsky: people like him were radical negators of Russian imperial oppression. But resistance to Russian hegemony alone was not enough: young radicals like Dzerzhinsky were searching for an alternative community, and not all in his generation identified with national causes, which in any case were very difficult to formulate given the region’s multi-ethnic and multiconfessional make-up. Originally destined for a career as a Catholic priest, Dzerzhinsky came to utilize methods of the Inquisition against the party whose catechesis he preached. Only ten years later, after his death in 1926, Dzerzhinsky would symbolize to hundreds of Russians and other peoples of the Soviet Union who had fallen out of favour with the new Bolshevik regime what Count Muraviev had symbolized to the Lithuania of his childhood: a brutal hangman. Unsurprisingly, the dismantling of a Dzerzhinsky monument on one of Moscow’s prominent squares (and still the location of Federal Security headquarters) marked the symbol of Russia’s de-Sovietization in the 1990s. Yet Dzerzhinsky’s apologists, in the 1920s as now, emphasized the importance of the chivalric ideal for his work. Indeed, to some, the secret services agency that he helped found – the Cheka – was comparable to a secret order in which certain ideals of virtue were cultivated in the name of a higher good. The ideational arsenal for rebuilding an alternative sense of chivalry was evidently convertible into a number of different projects in the post-imperial era.

Dzerzhinsky and Rosenberg shared a desire not only to find new post-imperial orders but also to re-enchant modernity through a new look at Europe’s medieval past. As a resident of Reval, Rosenberg was aware of being a citizen endowed with the privileges of the Russian Empire’s most modern, Western face. Here were some of its highly capitalized and most modern factories. Coming from a moderately wealthy, middle-class background of German merchants himself, he took up the opportunity of acquiring a solid education in a promising field, civil engineering. Moreover, gruesome as it seems in hindsight, he embarked on what seemed to be a growing sphere of work in this field. His diploma project, which he finished while his university was evacuated to Moscow, was the design of a new crematorium for the city of Riga. It was a modern, even a radical project, for the Russian Empire, because the Orthodox custom did not allow it, but it was a technology of the future that had already been well developed by this point in western Europe. Rosenberg’s project was never built, but Soviet Russia eventually turned cremation into a general practice from the mid-1920s onwards. The Nazi regime took the technology to a different level altogether, using it for the most unimaginable act of destruction, the mass incineration of millions of civilians murdered by the Nazis. It was only in his mature years that the contrast between medievalism and modernity reached new heights. Rosenberg and many of his social circle desired simultaneously a new age of chivalry and a new modernity, the honour code of an exclusive order and the extraordinary killing of innocents on a mass scale.

Rosenberg was a modernist whose modernism came from negating previous practice. Rosenberg’s initial choice of engineering as a profession reflected the status of this profession in Riga, one of the Russian Empire’s most modern and most ‘European’ cities. Its most representative buildings expressed all the stylistic stages of European urban history, from Romance to Renaissance to art deco. The most recent buildings were designed by a regional star architect, Petersburg-educated Mikhail Eisenstein. But the most iconic architectural landmarks of the Baltic were the medieval spires of the city’s medieval silhouettes and, in the countryside, the ruined castles of the Teutonic Orders.

Likewise, the middle-class student fraternities like Rubonia looked as much forward as back to a mythical past. They had their devises modelled after the old Crusaders. Rubonia’s was ‘With Word and Deed for Honour and Right’. Urban representative buildings such as the House of the Blackheads, a Renaissance building dating back to the sixteenth century, had coats of arms attached to them, which were modelled after the coats of arms of aristocratic families. In the form of reliefs attached on their fronts and painted on wooden doors, they displayed ties between the Hanseatic cities of Novgorod, Bergen, Bruges, and London. Other symbols included images of a moor and St. George’s cross, which demonstrated the historic origins of the association in the chivalric circle of the Knights of St. George in England, who celebrated their union with feasts in honour of King Arthur since the fourteenth century.

There were ties between student fraternities which were restricted to middle-class students only and the medieval guilds. The most famous of them, the Brotherhood of Blackheads, was an association of unmarried merchants whose chivalric and monastic ideals excluded nobles from membership. It was a tradition, however, to welcome members of high nobility, and particularly dynastic rulers, incognito, and the walls of the brotherhood’s congregation halls were adorned with portraits of monarchs. Among such incognito visitors had been three Russian tsars, Peter the Great, Paul, and Alexander I, as well as German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Their festivities were called Artus courts. Their original patron saint was St Maurice, the Theban Moor who in the third century AD fought for the Christian faith and died a martyr’s death. The organization’s ties to the Dominican order went back to a period in the fourteenth century, when a group of foreign merchants helped the Dominicans establish themselves in the Baltic littoral in their defence against an uprising by the local pagan population. The first merchant associations of this kind had formed in England and then expanded to the German lands, and especially to the Hanseatic cities. From a chivalric organization for high nobility, which was modelled on the mythical memory of King Arthur, it had been transformed in the cities of the Hanseatic league into a Christian association of merchants who combined the ideals of chivalric virtue with the understanding of virtue associated with monastic life. Older members of Rubonia who were active in suppressing the 1905 uprisings against the Tsarist Empire included Max Erwin Ludwig Richter, who later ennobled himself by marriage to become Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, and who joined the Cossacks during the Civil War; and Otto von Kursell, an architect and caricature painter.Footnote 15

After 1905, but even more so, after 1919, many more Germans, especially those of noble background, fled the Baltic littoral and were now settled in the successor states of the German Empire, mostly in Bavaria. In the Baltic lands, they were seen as ‘Germans’. In Germany, they now defined themselves as ‘Balts’, die Balten. In the latter half of the twentieth century, the role that intellectuals of Baltic background played in the forging of Nazi ideology, particularly when it comes to the ideas of German expansion in eastern Europe, has come more into focus of historians’ attention. Some scholars even speak of a streak of ‘Baltic eugenics’ in Nazi ideology, mentioning the role of biologists like Jakob von Uexkuell and Lothar Stengel von Lutkowski alongside Alfred Rosenberg’s and that of the non-Baltic race theorist Hans Günther.Footnote 16 To understand more precisely how these ‘Baltic’ ideas became so central to Nazi ideology, however, we need to delve more into the cultural history of post-First World War Munich.

The aristocratic ideal in Munich: rereading Politics as a Vocation in its social context

It was Alfred Rosenberg’s wife Hilda, a dancer from Reval who had trained in Paris, who wanted to move to Munich in 1918 because of the city’s reputation as one of the centres of modern dance. One of the Munich-based dance teachers was Edith von Schrenck, whom Rosenberg’s wife knew from her studies at the Dalcroze Institute in St Petersburg, an institute of modern dance and eurythmics run by Prince Volkonsky, who had been educated at Hellerau near Dresden. Also in Munich, the choreographer Rudolf von Laban formulated his first ideas about dance, which laid the foundation for his work as a prominent figure in Goebbels’s culture industry, before he moved to England.

Intellectuals and politicians who had passed through Munich between the 1900s and the 1920s had different social, geographic, and political trajectories. This mixture produced new political visions that reached far beyond the borders of the German Empire. A year before the revolution of 1905 in Russia, for instance, Leon Trotsky settled there to edit his revolutionary newspaper Iskra (Spark). Helphand, alias Parvus, an entrepreneur from Odessa who ended up organizing Lenin’s passage to Russia, lived there around the same time. But most people who arrived in Munich did not choose the city for political reasons; in fact, they were all attracted by the city’s promise of alternative lifestyles, particularly, in the visual arts, in theatre, and in modern dance.

The crowd that flocked to Munich in the last months of the First World War and the early years of the republic was still inspired by a search for alternative life forms, as those earlier generations had been. Munich’s Suresnes Palace, an eighteenth-century residence for the Wittelsbachs, became available for rent as an artists’ space, where Paul Klee had a studio in 1918, and where expressionist poet Ernst Toller was hiding after the failure of the Eisner government in 1919. During the war, another Wittelsbach palace, the Prince Georg Palais, had become the site of charitable activities sponsored by the Bruckmanns, publishers with wide-reaching connections, who organized a series of much-attended lectures in the series ‘War relief for intellectual professions’. Lectures on poetry and on antiquity were particularly prominent. Renting an apartment at Villa Alberti, poet Rainer Maria Rilke was among those both attending and giving talks on Roman antiquity to Munich’s elites, before he left the city in 1919. As Munich became of Europe’s first socialist republics, along with Hungary, it attracted particularly intellectuals of the radical left, who came here from Vienna. Anarchists, revolutionaries, counter-revolutionaries, they all gathered at places such as the Café Stefanie to discuss the crisis of modern life.

Like Laban, whose family name, De la Banne, denoted a French familial origin, many of the Bohemians in Munich were men and women of high nobility who sought an escape from traditional society. A significant number of them came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Munich’s official institutions, such as the Academy of Art and the University, were the first point of entry for many who flocked to the city for its art, but these soon found smaller and more informal circles. Munich’s Fine Arts Academy around 1900 was more progressive than both Vienna’s Academy and that of Berlin. But in addition to Munich’s traditionalists like Franz von Lenbach, it also had a group of more radical painters whose association, the Secession, mirrored an eponymous organization in Vienna and promoted internationalism in art since the turn of the century. This tension attracted independent artists like the Slovenian painter Anton Ažbe, who would in turn draw affluent students from across Europe to the city. Thus by the beginning of the twentieth century, the city had established a charisma of its own, which distinguished it from other German cities. It was more remote from government affairs than Berlin but also less provincial than cities like Weimar or Darmstadt. The city provided something for artists and intellectuals of high society as well as lower- and middle-class representatives. In his memoirs, written shortly before his execution at Nuremberg, Rosenberg recalled arriving in Munich with a sketchbook of watercolours drafted in Reval and in Skhodnya near Moscow, which he was trying to turn into sellable pieces of work on Munich’s art market,

With the end of the First World War, the period of cultural radicalism in Munich was followed by ten years of radicalism, in which the conflict of forces struggling for Germany’s future was particularly palpable. On 7 November 1918, the Wittelsbach King Ludwig III, who had only reigned since 1913, fled to the Austrian castle of Anif near Salzburg, where on 13 November he typed a declaration releasing all civil and military servants of his state from their duties, without formally resigning himself. The Bavarian king was one in a small group of five German heads of state who, like the Habsburg Emperor Karl I, had refused to abdicate; the majority, seventeen monarchs and princes, resigned on behalf of themselves and their families. Like all of them, Ludwig too feared for his life; he moved between castles in Hungary and Austria before returning to Bavaria, where he died in 1921.Footnote 17 The socialist leader Kurt Eisner had already declared Bavaria a Republic on 7 November, two days before Scheidemann and Ebert would do so in Berlin. Eisner interpreted Ludwig’s declaration as a form of resignation. In this period of upheaval, another intellectual to move to Munich was the Viennese philosopher of science and economist Otto Neurath, who was appointed head of the Central Planning Office of the Munich Council Republic. In May 1919, some 600 people were shot during clashes on Munich’s streets, and others were imprisoned.

Among the moderate intellectuals who also settled in Munich in the years of revolution was the sociologist Max Weber. Having recently recovered from a nervous breakdown, he favoured the Bavarian capital over offers of professorial positions at universities in Vienna, Bonn, Berlin, and Frankfurt. His choice of Munich as the place to revive his academic career after a break of twenty years was informed by personal and professional connections, some of which established ties to the heart of the republican socialist government. In the winter of 1918/19, Weber published a series of programmatic works in a set of special pamphlets published by the nationally renowned Frankfurter Zeitung under the series title ‘On the German Revolution’, through which he wanted to establish the theoretical foundations for a republican order in Germany from a liberal standpoint.Footnote 18 Not only would the foreign powers not allow Germany to be restored in her previous, dynastic order, Weber argued; this was not in Germany’s interests either. Instead, Weber advocated a solution for Greater Germany, whereby Prussian sovereignty would be crushed in favour of a federal system of nearly equal states.

Only a year after the revolution had begun, Eisner was assassinated, and Neurath, the economist Edgar Jaffé, as well as other leading members of Eisner’s socialist government were put on trial for treason. Max Weber, who did not share their radicalism, nonetheless appeared as a defendant in court: although a more outspoken critic of the left, in his actions he was far more sympathetic to the socialists and anarchists than he admitted in print. He did not live to see this, having died in 1920, but it quickly became apparent that the threat of violence was at least as great, if not greater, from the right as it had been from the now declining communist left. In March 1920, Wolfgang Kapp, a leading member of the All-German Union, and General Walter von Lüttwitz, then used one of the disbanded military corps, the Marine brigade Ehrhardt, in an attempt to seize power. The putsch was thwarted by a general strike of the trade unions and a form of passive resistance by the military bureaucracy. In 1923, Adolf Hitler, who chose to settle in Bavaria having been released from the Bavarian infantry, which he had joined as a volunteer, undertook a putsch in Munich’s Beer Hall, during which he proclaimed himself Reich chancellor, again with support from former generals such as Ludendorff. After it failed, one of his leading supporters, Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, was shot at the scene, while Hitler was taken prisoner for one year. This period of imprisonment not only gave him time to write his main ideological treatise, Mein Kampf, but it also provided him with the right status for becoming a celebrity in Munich. While in the short term unsuccessful, these Munich-based attempts at destabilizing the republican regime paved the way for the foundation of the Third Reich merely ten years later in Berlin.

Much political action in Munich occurred not only on the streets but in the private circles and salons, as well as in artistic associations that ranged from public to exclusive. While men clearly dominated radical street politics, behind the front doors, but still very much in public, women were very influential. Once again, among Munich’s high-society ladies, members of high nobility were particularly prominent: salonière Elsa Bruckmann, née Princess Cantacuzène, emerged as a hostess of a series of lectures in support of the German war effort during the war and continued to bring together representatives of different political and social groups at her home in Nymphenburger Str. Other ladies of high nobility included the Prussians Else Jaffé, née von Richthofen, and Franziska ‘Fanny’ von Reventlow, who was a celebrity of experimental life. She lived in a prominent cooperative Wohngemeinschaft with the art connoisseur Bohdan von Suchocki and Franz Hessel, a novelist, in Munich’s Kaulbachstrasse. Subsequently celebrated as one of the lead protagonists of the film Jules et Jim, based on Hessel’s memoirs, her aura, just as the city’s, was the birthplace of a new type of human being: the ‘homme curieux’.Footnote 19 Members of these circles made the practice of experimental life forms into the content of their political message. Experimental communities with prominent Munich connections included the society of the Eranos circle, a loose group of intellectuals of high society interested in psychoanalysis, social cooperative movements, and alternative forms of spirituality, which gathered for regular conferences at Ascona’s Monte Verita, a Swiss commune, between the 1900s and the 1930s. Two other circles of intellectuals, philosophers, and poets, who sought to establish a secret society or even a state within German society in transition between states, which had a base in Munich, were the Cosmics around writer Ludwig Klages and Bachofen, and the circle of young men around poet Stefan George. Though overwhelmingly masculine, these circles included some of the more radical attempts to revisit the sources of antiquity in search of new conceptions of masculinity and sexuality; they also shared with their more left-leaning fellow residents an interest in challenging bourgeois conceptions of marriage and such like.

It was in these circles that sociologist Max Weber observed the social types which he described as ‘charismatic’: a form of social power which individuals exercise, and which transcends the apparently significant differences between premodern and modern societies.Footnote 20 The themes of their gatherings were often very broad: to define European identity and to broaden cultural connections; to pursue interests in various kinds of Orientalisms; to discuss the potential threats posed to Europe by the non-European world and the Soviet Union; to discuss the differences between the ‘Latin’ and the ‘Germanic’ peoples of Europe, of Catholics and Protestants, and the place of non-Christians in Europe; to discuss the character and, in some cases, the danger of National Socialism and fascism.Footnote 21 French historians describe the activities of these social circles as ‘européisme’, a meta-ideology in which many otherwise conflicting parties met and mingled. What connected these societies was their shared admiration of sacred and secular medieval orders associated with chivalry and monastic knighthood. Somewhat related to these associations, albeit less socially exclusive, was the neo-medieval Thule society, which met at Hotel Vierjahreszeiten. Thule was the ancient Greek word for the northernmost known corner of Europe. Its membership was mixed; alongside some members of nobility, such as Prince Gustav von Thurn und Taxis and Rudolf von Sebottendorf, most members came from lower middle-class backgrounds. One of the authors connected to the circle was the playwright Dietrich Eckart, a Frankonian, who had moved to Munich from Berlin to become the editor of an anti-republican journal, Auf gut Deutsch. In 1921, he introduced Rosenberg to another outsider to Bavaria, Adolf Hitler, who, despite being a subject of the Austro-Hungarian army, volunteered to join the Bavarian army during the First World War and thereafter returned to Munich, rather than Vienna, in the hopes of resuming a more successful career than his failed attempts at art and architecture in Vienna had intimated. Both ended up working for Eckart’s journal. Eckart, a failed lawyer and a somewhat more successful playwright, returned to Bavaria after a brief stint in Berlin, where he was befriended by a member of Wilhelm II entourage, Georg von Hülsen-Haeseler; his theatrical experience subsequently was used to coach Adolf Hitler in public speaking. Other members included Rudolf Hess, Heinrich Himmler, and Alfred Rosenberg. The ideological orientation of this society was not only anti-republican, but in general directed against the ideals associated with the Enlightenment.

The New Order State that Rosenberg began projecting first on paper and in public speeches during the Russian Civil War was a pastiche from the medieval history of the Baltic region, the Italian city states, and the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. This broad ideological structure, for which Alfred Rosenberg was one of the chief contributors, was then further supplemented by other, more modern ideas: the association of a modern, unified press, as well as the creation of one, streamlined workers’ organization and the commitment to modernization and technological progress.

By studying the ideas of individuals whose actions eventually shaped an entire generation, we can turn individual biographies into group biographies, a way of seeing the past in the shape and the scope of human lives. But to understand more how their ideas intersected, and how exactly the ideas of some individuals gained more traction, we also need to investigate settings in which their speech acts are being received. One such setting is official congresses and conferences. Other settings are private dinner parties and reunions, insofar as they have been rendered into textual forms in diaries and memoirs. The case study in this chapter focuses on an international congress on the future of Europe, which the fascist government convened in 1932. It united representatives of a wide range of views on Europe’s future in Rome.

Vanguards for a noble race? Nazi ideology in transnational context

The neo-medieval ideal as a factor in the formation of Nazi ideology has been a recurrent theme of some of the genealogies and intellectual biographies of leading Nazis: from the esoteric readings of Hitler and some of his followers from their early days in Vienna and Munich to the foundation of their own new orders such as the SS.Footnote 22 Historians have recently highlighted the seriousness with which the Nazis thought of their project not only in terms of nationalist and socialist paradigms, but also in terms of empire building.Footnote 23 In the choice of orientation between traditional and modern, between restoration, reform, and revolution, the idea of chivalry appealed as a timeless alternative: like charisma, it promised to infuse the best of the traditional against the worst of the modern.

Munich in the period from the November Revolution until 1923 provides a microhistory of a milieu in which National Socialism became socially acceptable. They were also settings in which the combinations of chivalric and modern were tried and tested, often in a way that confronted old elites like Prince Rohan with the newcomers and outsiders like Rosenberg. Mixed couples of high nobility and bourgeoisie, like the Bruckmanns, were as important in creating new connections between recent migrants to the city, as were lower middle-class figures like Dietrich Eckart, who had come to Munich from not quite so far; intellectuals like the circle of Stefan George played as important a role as the anti-intellectual Russian monarchists who had come here after the collapse of the White Army in the Russian civil war.Footnote 24 One of the things that united these people was a shared myth of a lost historical past, which many associated with an aristocratic ideal: the image of the chivalric past in eastern Europe and Russia, where organizations such as the Teutonic Order, elite merchant unions, and German colonists, all believed to raise levels of civilization in what they thought of as a backward part of Europe. While Munich was not the birthplace of Nazi ideology, it was certainly the place where its leading ideologues and supporters met and where, based on their mutual attachment, its different strands became amalgamated.

Many in the circle surrounding the publisher Hugo Bruckmann and his wife Elsa perceived the abdication of figures like the Wittelsbach King Ludwig III as a tragic event. Hugo Bruckmann, the publisher who since the beginning of the First World War began actively to promote literature of pan-Germanic ideology by H.S. Chamberlain and others, endorsed a cult of chivalry and aristocracy, as did many in their circle, such as Stefan George and his circle of followers. Elsa Bruckmann was believed to be the direct descendant of Byzantine Emperor John VI Cantacuzenus; her nephew, Norbert von Hellingrath, was a member of Stefan George’s circle and an editor of the first complete works of Hölderlin, whose romantic poeticization of Germany tied it to the ancient world of the pre-Socratics. All Wagnerians, this circle also cultivated their ties to Wagner’s neo-medieval estate at Bayreuth. One of the commonly seen figures in their salon was Karl Alexander Müller, the historian who became the editor of Süddeutsche Monatshefte, an increasingly völkisch magazine. From 1930 to 1936, he served as director of the Institute for the Study of the German People in the South and the South East (Institut zur Erforschung des Deutschen Volkstums im Süden und Südosten), whose aim was to establish a comprehensive analysis of the impact of German culture on European civilization. It continued the ethnographic work of Baron August von Haxthausen, paving the ground for historically founded claims of legitimacy for Nazi expansion in the East. By the time Hitler had begun composing Mein Kampf, in 1923, his recent acquaintance Rosenberg had already developed in a nutshell his idea about the importance of the medieval nobility in creating the ideal type of the Aryan. Both interacted at Elsa Bruckmann’s salon with its emphasis on the need for the rejuvenation on the old nobility.

Their joint project, the Nationalsozialistische Monatshefte [the National Socialist Monthly] was the main platform for debating the cornerstones of a new ideology. At the beginning, one of the unifying themes was a critique of the old national bourgeoisie, a point of connection for rising social groups of which Rosenberg and Hitler were representative, with old elites. In the first issue from 1930, one of the paper’s ‘pedigreed’ contributors, Count Ernst von Reventlow, spoke of the ‘nemesis’ of the bourgeoisie.Footnote 25 Goebbels echoed in the same issue, speaking of the anaemic and subservient psychology of Germany’s bourgeoisie.Footnote 26 By 1933, Goebbels was ready to declare that the Nazi seizure of power, and not the end of its monarchy, was Germany’s real revolution, which pointed to a third way beyond Right and Left.Footnote 27

In this process, nobles of old lineage, as well as people of lower social backgrounds and those who aspired towards nobility by adopting a noble surname – such as the ideologue Josef Lanz von Liebenfels – all played slightly different roles. Visibility, which, as social theorist Georg Simmel insisted, was one of the key sources of aristocratic privilege, was not only given through symbolic markers such as having the right particle. Nobility was traditionally also performed socially, one had to ‘pass’ in order to be accepted as noble.

Paying attention to the intellectual genealogy of this ideal does not provide an explanation for all the aspects of the Nazis’ appeal, such as why certain groups or residents of certain regions were more likely to vote for the Nazis. But what it can explain is how the Nazis succeeded in ultimately reaching such a diverse population. In explaining Nazi appeal, scholars pay particular attention to the years from 1928, when the Nazi party only had a support base of 800,000 voters, to the Reichstag elections of 1930, when six million voted for the party.Footnote 28 Another focus of interest is the growth of the Nazi propaganda machine following the seizure of power in 1933, with its powerful synaesthetic impact through radio, film, and public exhibitions. But by this point, its influence already had a snowball effect. Far more open-ended, and therefore more interesting, is the question how the Nazis became the Nazis as the world got to know them in the first place, and for this, we need to look in more detail at the intellectual atmosphere and social circles in which the chief ideologues – Adolf Hitler, Alfred Rosenberg, Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler – mingled.

Political ideals have not only an intellectual genealogy such as the ‘palingenetic myth’ which underpins the idea of racial superiority in Nazi ideology. They also have a social one. The social milieus of cities in transition, like Vienna, as described by Brigitte Hamann, and Munich, described by Richard Evans, and more recently, Wolfgang Martynkewicz, provided the material that forged these disparate images together.Footnote 29 The image of declining dynasties and the ideals of a rejuvenated nobility was a dominant paradigm of discourse in these circles, one that was promoted not only by poets of bourgeois origin like Rilke but also by nobles themselves, particularly hostesses and Bohemians such as Elsa Bruckmann, Fanny von Reventlow, and the von Richthofen sisters.

One of the last issues of Nationalsozialistische Monatshefte before the Nazis took power in Germany was devoted to the Crisis of Europe.Footnote 30 At the heart of the paper was coverage of Alfred Rosenberg’s recent visit to Rome, where he was one among many venerable speakers from different European countries. In his editorial to this issue, Adolf Hitler noted that the congress organizers had refrained from inviting leading politicians of their time, opting instead for the most noteworthy ‘intellectuals’, writers, and politicians who had once occupied an important role and felt a vocation to do so again in the future. This explains the combination of ‘outstanding historians’ with ‘renowned politicians’ such as Count Apponyi, Rennell Rodd, former British ambassador to Italy, and others. The aim was not to turn this into a discussion of ‘diluted internationalism’ of a League of Nations but to create instead a firm ‘sentiment of national socialism’. In this spirit, the paper noted four attempts to create a united Europe: in the Middle Ages, through the Holy Roman Empire; in the modern era, under Napoleon; after the Great War, through the League of Nations; and in the same period, in the form of the Bolshevik revolution. All four attempts failed for different reasons, and it was the task of the gathering at the renowned Renaissance villa Farnesina to find the resources for Europe’s true regeneration. It was particularly important for this endeavour, Hitler emphasized, to stay away both from Bolshevism and from the Paneuropean utopianism of a Coudenhove-Kalergi.

Ten years prior to the Nazi monthly, Count Ernst von Reventlow founded the Reichswart [Imperial Herald], a party-independent magazine, which favoured Austro-German unity, demanded a revision of the Versailles treaty and a new colonial policy for Germany. Reventlow himself was a member of the German National People’s Party (DNVP) until 1927, when he joined the Nazi party.Footnote 31 The paper retained a curious combination of being committed to a systematic and institutional anti-Semitism in Germany, whilst regularly picking up on reports of anti-Semitic purges in the Soviet Union, as early as in 1930.Footnote 32 Ernst’s younger sister, Fanny von Reventlow, was, by contrast, at the heart of the Schwabing Bohemians, which included a different kind of fascination with the aristocratic and an internationalist anti-bourgeois community: the circle around artists such as the exiles of minor Russian gentry, Marianne von Werefkin and Alexej von Jawlensky, the Cosmic circle and the community that would travel regularly to Ascona’s Monte Verita gatherings. This small network of associations shows the ambivalence of neo-aristocratic anti-bourgeois sentiment in post-war Munich and simultaneously the personal interconnectedness between intellectuals of quite opposing political views.

The chivalric ideal acted as an ideational glue for a very disparate community in interwar Munich. Above all, it gave general recognition to newcomers from the periphery, such as Alfred Rosenberg and Adolf Hitler, who came out of the Great War with a great sense of disorientation. Their radicalization was shared by an entire generation, but not all of its representatives felt the need to form actual alternative social and ideological networks for the rebuilding of a future empire. To the detriment of European society, of many neo-aristocratic dream projects born in Munich in the 1920s, it was their project of a Third Reich and their idea of a neo-medieval order – the SS – that succeeded in the subsequent decade. Later, Rosenberg’s appointment as a special Commissioner for the Eastern Territories in 1941 gave him further opportunities to put his mythology of a reformed eastern European colony governed by a Teutonic Order into practice. Alongside mass deportations of the Jews, Rosenberg was in charge of resettling the population of Baltic nobility in the formerly Polish area of the Wartheland.

As soon as 1935, Germany, unlike most other central European states with the exception of Hungary, revived the old status of nobility, even though the Nuremberg laws of 1935 required nobles of known old lineage to provide proof of racial purity until 1800. At the same time, leading members of the Nazi party sought to regain the cooperation of nobles in their project of national renewal, which was done both at the level of reintroducing new forms of rank to the army and at the level of co-opting nobles who had held possessions in what was now no longer Germany into projects of re-colonization of these territories under the Nazi aegis. As recent historians have argued, such attempts were partially successful, particularly when it came to establishing partnerships between the Nazi party and those associations of noblemen that had already moved to the political right before the Weimar Republic had been conceived. The primary organization to cooperate with the attempts by the Nazi party to reinstitute the nobility was the Deutsche Adelsgenossenschaft.Footnote 33 Indeed, throughout its time in power, the Nazi government in Germany redefined both its concept of nobility based on race and its policies towards organized nobles’ organizations such as the DAG.Footnote 34

The authority in the party who oversaw the reform of the existing nobility in Germany was Hans Guenther, minister of health. In some sense, Guenther sought to reverse the radicalism of Weimar constitutional attempts to remove the institution altogether.Footnote 35 Already in his time as a constitutional lawyer in the Weimar Republic, the jurist Carl Schmitt had called the movement to abolish the nobility a form of ‘Jacobinism’.Footnote 36 In Austria and Germany, the first constitutional assemblies of the new republics implemented decrees abolishing all forms of noble status in 1919. The nobility was abolished, along with ‘its external privileges and titles awarded as a sign of distinction associated with civil service, profession, or a scientific or artistic capacity’. Nobles were to become ‘German Austrian citizens’, equal before the law in all respects.Footnote 37 In republican Germany, nobles were allowed to continue using their titles as part of their name, without the right to inherit them.Footnote 38 Nazi law partially reversed these changes.

Nobility of Blood and Soil

Another author to be inspired by Rosenberg, albeit already during the period of Nazi rule, was Walther Darré. His Neuadel aus Blut und Boden [New Nobility from Blood and Soil] cast the peasant as a bearer of Germanic customs in the centre of attention. Frequently referring back to the architecture and history of the Ostsee provinces, Rosenberg continuously emphasized the achievement of the Teutonic Order as a civilizing force in eastern Europe. Visiting Westphalia, Rosenberg was reminded not only of the connections between the old families of the Teutonic Orders that had moved from here to East Prussia and the Baltic but also of the entourage of Widukind, the ancient Saxon knight, whose descendants still honoured him in the form of the Seppelmeier Hof, a traditional residence of ten families or so in Westphalia and Lower Saxony who were thought of as Widukind’s descendants.

The aristocratic ideals of exclusivity, military prowess, and cultural patronage were eventually divided among different offices. Alfred Rosenberg became the chief of an eponymous cultural department, which collected artworks from across Europe and established a network of museums of racial culture as well as exhibitions on the history and future of Europe across Nazi-occupied territories and the new empire’s German heartlands. In the meantime, another newcomer, Heinrich Himmler, founded the neo-chivalric Schutzstaffel SS, where, likewise, ideas of ‘fidelity’ and ‘honour’ were applied to the Fuehrer.Footnote 39

Government correspondence from the Nazi period reveals an internal debate about whether or not to acknowledge that some families had a ‘higher significance for the state than other families’, – the internal definition of nobility depending on other than racial purity – implying also ‘higher tasks and duties’ for nobles in return. ‘In this connection’, one minister argued, ‘we will also have to determine whether we should grant such a special status exclusively to families of former nobility, or also consider admitting new families’. One means of helping to make this determination was to work with anti-Semitic groups within aristocratic organizations, resulting in a follow-up to the Gotha Almanach of nobility and listing all ennobled Jews in a separate edition called the Semi-Gotha. In its occupied territories, the Nazi government even commissioned book-length studies on how to distinguish, for instance, Polish nobility of Slavic origin from those of Jewish origin by looking at surnames.Footnote 40 The idea of the nobility as a superior group within the general population contradicted Nazi ideas about the racial superiority of the Aryan race, all members of which were supposed to be mutually equal.

The Nazi government had particular difficulties in addressing the issue of aristocratic privilege. On the one hand, the ideal of the Teutonic conqueror of eastern Europe was important for the ideology of recolonizing the East. Hitler and Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg had discussed both the Teutonic Knights in East Prussia and the Baltic as a model for the Nazi takeover of eastern Europe. In Mein Kampf, the nobility remained a more ambivalent concept than in Rosenberg’s work, in which the nobility appears first as an example of racial degeneration, based on examples of dynastic incest among families such as the Habsburgs. Hitler’s distaste for the Habsburg dynasty was balanced by his acceptance of Franz Josef’s authority when he was emperor, as well as an outright admiration of the Hohenzollerns. Likewise, Hitler’s emphasis on the nobility’s history of degeneration and racial mixture with Jews was counterweighed by his idealization of the medieval chivalric orders. Further, nobles are condemned for introducing Jews to European high society.Footnote 41 Only the Teutonic Order, which had colonized the Baltic littoral and some parts of eastern Europe beginning in the thirteenth century, receives a positive treatment from Hitler. In his so-called Second Book, though not published in his lifetime, Hitler was concerned with the National Socialist concept of a new empire in which an Aryan nobility plays a leading role.Footnote 42

Following this logic, the Nazi government partially reinstated some noble privileges after 1935, and indeed managed to create attractive positions of power for nobles such as Gottfried von Bismarck and the von Hessen family, while also maintaining its image as a revolutionary and socialist party.Footnote 43 Thus, in keeping with republican legislation, noble titles under the Nazis continued to be seen as part of the family name. Nobles were mere ‘members of families with a noble name’, although the regime itself provided more exclusive opportunities for nobles than the Weimar Republic.Footnote 44 Nobles were recruited for active collaboration with the regime in connection with the conquest of eastern Europe. Following the Hitler–Stalin pact of 1939, as Hitler’s chief ideologue for Eastern colonization, Rosenberg invited nobles from the Baltic region to lead the colonization of parts of Poland and Ukraine and to employ their knowledge of agricultural organization since feudal times for a new development of the region, using Polish forced labourers. For this purpose, the Nazis even briefly reinstated the Teutonic Knights. On the other hand, the ideology of the Aryan race had no room for an exclusive group within the community of Aryans.

Subsequently, western European and North American historians of modernity have constructed ‘special paths’ in establishing separate genealogies of Nazi and later, Soviet totalitarianism, which were quite different from the idea of a more normal, more humane modernity that led from empires to modern nation states. With greater distance and more documentary evidence at their disposal, it is only since the end of the Cold War that historians have gradually become aware how many of these representatives of different national and political regimes had come from a shared ideational and social background. Totalitarian and democratic states had the same genealogy, even though historical accounts like Hannah Arendt’s Origins used this genealogy to draw out contrasting lineages. The phrase ‘Iron Curtain’, which many attributed to Winston Churchill, we now know, had been traced back to a speech by Joseph Goebbels and perhaps even further back.Footnote 45 The image of a Europe containing separate genealogies, with one leading from ancient Greece via Rome to modern Europe, and two rogue branches leading to Bolshevik Russia and the capitalist United States, was first printed in a Nazi propaganda brochure distributed in Vichy France in the 1940s.Footnote 46 Not only the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, which signed a pact of non-aggression in 1939, but also informal representatives of western European and American societies and the Soviet Union were much more connected than the public discourses of these states conveyed. In fact, these Europeans who contributed to mass civilian destruction had a common past in the system of imperial rule, which the Habsburg, Hohenzollern, and Romanoff dynasties had overseen for many generations.

Rome as a shared capital of imperial nostalgia

‘Duce, Eccelenze, Signore, Signori!’ With these words, the venerable Italian inventor of the radio, Guglielmo Marconi, opened the Congress on Europe at Rome’s Capitol in November 1932. In what would be his last public role, Marconi now served as honourable president of the Royal Academy, which had recently been reconstituted under Mussolini’s tightening control.Footnote 47 A resurrected institution of the Enlightenment in a resurrected city, the Academia had invited a wide range of leading intellectuals and politicians to debate the future of Europe. Mussolini himself, a new Cesare Borgia or perhaps a new Caesar himself, was present at the opening, as was the king, Vittorio Emmanuele III, and other royalty. Among the list of Excellencies, only one was markedly absent: Pope Pius XI. Relations between the rising Mussolini entourage and that of the papacy had reached their lowest point around that year.

The ideal of debating Europe in its oldest capitals was at the heart of a new internationalism that struggled to find its own voice against the Catholic internationalism of the Vatican, on one side, and the Protestant internationalism of Wilson’s Geneva-based League of Nations, on the other. In this project, the congress fulfilled the function of consolidating a transnational group of politicians, academics, industrialists, and writers. It combined archaic and modern, a fascination with the past and the search for modernity that was so characteristic of the political generation that formed this period. The congresses were also exclusively masculine; no women were invited, and those who attended were the wives, secretaries, and daughters of delegates.

The beginning of the Volta Congresses went back to the year 1925, when a group of intellectuals under Mussolini began working on a new philosophy of Europe.Footnote 48 One of them, Francesco Orestano, a Kant and Nietzsche scholar and a lawyer, had studied in Germany and belonged to the first generation of Nietzsche followers. Their plan was to use an international congress across nations and disciplines in order to discuss what the identity of Europe would be: its unity; its unique concept of civilization; the nature and causes of its current crises; the relationship between Europe and the non-European world, and particularly, the colonial question. The latter was the subject of an additional congress on Africa. The congress attracted an illustrious crowd of academics, journalists, and former diplomats. The organizers worked under the auspices of the Mussolini-controlled Roman Senate. Even the conference programme was printed at the Senate’s own publishing house. The financial backing came from the Volta foundation associated with Edison Electric corporations.

The most obvious beneficiaries were the newcomers on the political scene, and those who travelled to Rome for the first time. On a group level, it was of far greater significance to representatives of those nations which either did not exist prior to the First World War or had significantly changed their constitution, such as Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the host country itself. This was also reflected in the disproportionately declining number of participants from other countries that survived the Great War more or less intact, such as Britain. It was particularly noteworthy that one new state was conspicuously absent because it had not received an invitation: the Soviet Union.Footnote 49

The meeting also brought together what could be called the Captains of Industry with the Captains of Science, eminent diplomats working for former empires such as Austria-Hungary, such as Count Albert Apponyi, as well as former diplomats working for still-existent empires, like the retired British ambassador to Italy, Baron Rennell Rodd. Events like these were not only a validation for Italy as the host country, and the Duce personally as leader of a neo-Roman Empire; it was also a validation for some of its participants.Footnote 50

Many of the more affluent representatives of the generation that gathered here in 1932 had witnessed the first major excavations of antiquity in their childhood. From the 1880s to the 1890s, hidden ruins of the Forum in Rome and the patrician houses in Pompeii were dug up. By the mid-1920s, archaeologists also discovered residential multistorey houses in Ostia. Now, in the 1920s, a new building boom in Rome underlined the classical heritage of the city with new representative buildings in neo-classical style.Footnote 51 Rome was to be a capital of the twentieth century. Excursions to the city were an integral part of the congress on Europe. A further congress on the future and colonial administration of Africa, held in Rome in 1939, after the Italian conquest of Lybia, included a special treat: a scheduled flight for delegates to the ruins of antiquity at Tripoli.

Events like the Volta Congress on Europe, and a follow-up congress on Africa, highlighted the international connections between what seemed rather different models of imperial attachment. Of 120 participants in the Europe congress, an overwhelming majority had served in leading diplomatic or military posts by the time the Great War broke out. These included military leaders like the Duke of Abruzzi, an ex-Hungarian minister of Austria-Hungary, the president of the French diplomatic academy, former diplomatic staff of the British Empire, and members of the League of Nations staff. Among the cultural figures were established intellectuals in their fields and nations, such as the archaeologist Charles Petrie, the sociologist Alfred Weber (brother of Max), the writer and diplomat Salvador de Madariaga. But a smaller group of men were the rising stars of a new generation of politicians and intellectuals. Chief among them were new political leaders and ideologues, like Mussolini and Alfred Rosenberg.

Among the scholars and writers invited to the congresses on Europe and Africa, there were also other authors whose fame had crystallized in the 1920s out of a similar mood of European decline and quest for a new political vision: Stefan Zweig, who sent his paper but did not attend in person; the historian Christopher Dawson; Tomasi Marinetti, who attended the Africa congress; Bronislaw Malinowski, the anthropologist, who at the Africa congress represented the British Anthropological Association; Prince Karl Anton Rohan, editor of Europäische Revue.

Moments like this congress can provide us with some insights on how different ideology-drafters mutually perceived each other’s ideas of the past in the light of the future. It is significant to see these men of different social standing, a different relationship to the former empires, and varying age be located on the same page of a congress staged with such symbolic panache. Rome was everybody’s capital, but many of the people who had arrived there had their own post-imperial projects on their mind. Prince Rohan attempted to recover the place of Vienna as Europe’s cultural capital. Count Apponyi and other representatives of the more disenchanted elites of the Habsburg era had been seeking to widen audiences by appealing to European expatriates in the United States. The British intellectuals saw London as a new Rome. For the representatives of the Soviet Union, who were not invited to the Volta congresses on Europe and Africa but were welcome at a special congress on theatre and the arts, the Fourth Rome was Moscow.Footnote 52 The German representative, legal internationalist Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, was a proponent of a new Germany based on the neo-classical foundations in Weimar, while others favoured Munich, capital of the secessionist Bohème. Finally, and most crucially for Europe, for the Nazis, represented by Alfred Rosenberg, the real capital of a new Third Reich was Nuremberg. Instead of Berlin, Vienna, or Weimar, the Nazi party chose this city, the former seat of the imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire, as a symbol of its power. Architect Albert Speer soon had it redesigned for the purpose of mass public rallies, and it was here where, three years after the congress in Rome, the party would pass its most significant piece of legislation, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935.Footnote 53

For the old elites, the congress made clear that their sense of self was still tied to the old empires. This was particularly true of the Habsburg nobility. The contrast between old and new elites became most marked in a clash over the historical roots of European identity that emerged in the speeches between Prince Rohan and Alfred Rosenberg. Rohan, who chose to publish his works in Berlin rather than in Vienna, pointing out that in Vienna ‘there is no Prince Rohan any more, only Karl Anton Rohan’, thought that the old ‘nobility’ now had the task ‘to transform the old values in a conservative way, according to its tradition, using the new impulses of the revolution’.Footnote 54 He wanted to create ‘unified Europe’ instead of an ‘ideological brotherhood of mankind’.Footnote 55 The new Europe, saved from Spenglerian decline, as well as the threats of Bolshevism and fascism, would be a fusion of aristocratic leadership and collective action by workers who, as he put it, were not mere ‘prols’ but conscious of belonging to a collective. The bourgeoisie, by contrast, ‘today already rare, will probably slowly disappear altogether’.Footnote 56

The Nazis’ effectively Prussianized account of European history was at odds with Rohan’s own continued espousal of the Habsburg Empire as a model of Catholic universalism, which was in a sense ironic, as the Rohan family itself had a glorious prehistory in the Protestant struggle of the Duc Henri de Rohan during the Reformation in France. In light of subsequent events, the rise of the Nazi party, another World War, and a much more significant collaboration between international parties in its aftermath, the congresses of the 1930s in Rome might seem peripheral to world politics. Yet for anyone who wants to understand the language in which an entire generation exchanged ideas about Europe before this exchange escalated in unprecedented levels of destruction, they are a rich field of study. What the congresses highlighted was the extraordinary degree of commonality that these different men shared, and the fact that those lines which divided them did not run along the political borders of Europe in their day. Instead, they were rooted in classical texts of the past, above all, Tacitus’s Germania. The contrast between them was between multiple ideas of Europe: a Latin and a German model of Europe’s greatness, modelled either after the great patrician aristocracy of the Roman past or after the ‘barbarian’; and a Nordic racial ideal. This was a generation of secularized Christians in which the conflict between Protestant and Catholic Europe had been transformed into the believed opposition between races: Nordic, Latin, and Slavic. Another commonality was their shared rejection of the Soviet experiment and the Bolshevik party. In this climate, it turned out that their conversation revolved around the question what kind of aristocratic past, what kind of patrician or chivalric, Romance or Latin, Nordic or Southern, was going to win.Footnote 57

This Volta Congress on Europe of 1932 served the purpose not only of identifying the crisis of Europe but also of giving legitimacy to a new, imperial vision of Italy that Mussolini and his circle were trying to establish. It was a moment of glory for Mussolini but also for the National Socialists, whose internal political triumph was yet to come. One of the key figures of the future, it turns out, was Alfred Rosenberg, by the beginning of the congress still a marginal figure.

Most speakers were forgers of new ideologies, of a new outlook on European identity and future, and most began their intervention with references to the crisis of the League of Nations, and the dangers of economic and political instability. One notable feature was the emphasis on an ecumenical and international project of rebuilding empire, which featured Protestant, Catholic, and, though to a much less prominent extent, Jewish intellectuals, but noticeably excluded Muslim and Russian Orthodox representatives. There were no representatives of Europe’s political Left. Likewise, there was not a single female delegate; women were only welcome as secretaries, wives, or daughters of delegates. In fact in the correspondence, a special point was made in emphasizing the distinction between wives and partners. A special translation service, the office of Dr Giuseppe Milandri, was drawn upon to help during the congress, although many of the delegates spoke at least two languages.

The press reports ranged from dispassionate accounts of how Europe’s dignitaries had gathered on the Tiber to angry voices arguing that ‘Europe had been robbed by fascists dressed in academic uniforms’.Footnote 58 The Journal de Genève reported that the atmosphere in Rome that year was one of euphoria over the new regime, which celebrated its first ten-year anniversary that year.Footnote 59 ‘Nothing could be less aristocratic, less conservative, than the fascist regime’, the journalist signed W.M. concluded, listing the new aqueducts, railways, and other innovations introduced under Mussolini’s rule. And yet, it was a noticeable feature of the Europe congress, as part of this year of festivities, that it included a noticeable number of delegates of old European nobility who had been public figures of Europe’s defunct continental empires. These individuals included especially families loyal to the Habsburg Empire, such as the Rohans, the Apponyis, and also Spanish and Swiss Catholic nobility. What they had in common was a particular espousal of Catholicism – the universalist, but not the socialist message – with an imperial form of internationalism. These residents of cities, no longer imperial subjects, and not yet national citizens, were now above all burghers: patricians in Rome, dandies in London, and consumers of culture in Paris.Footnote 60 They looked at these cultural capitals for guidance of the future. And yet it turned out that the most influential politicians of the twentieth century were not Romans, Parisians, or Londoners. They were men who had grown up in Europe’s lesser cities, places like Reval, Linz, and Tbilisi. Here, the aristocratic and chivalric ideals and neo-imperialist aspirations had a particular, more colonial inflection.

In the European cities suspended in the 1930s between old and new empires and new nation states, such as Munich, Rome, Reval, Königsberg, Geneva, and the Vatican, ideals of chivalry were quickly turned into programmes for new types of post-imperial orders. Here, new charismatic personalities saw politics as their vocation. They presented themselves to their public in the international language of a new aristocracy of the future. Liberals like Weber had high hopes in the capacity of cities to regenerate the European bourgeoisie through the production of democratic forms of charismatic empowerment.Footnote 61 But these less established former imperial subjects were not citizens of a democratic republic. Many of these transient burghers were looking at the old elites of continental Europe for guidance on how to revive empires.

A visitor to the National Gallery in London easily overlooks, as I have done many times, that the floor is also a space of visual display. Close to the main entrance, between the busy shops on the ground floor and the first floor’s galleries, two large mosaics show allegories of the British character and allegories of modern life. One of them, labelled Courage, has Winston Churchill taming a wild monster, probably of Nazism, arising from the sea.

The artist behind the mosaic, Boris von Anrep, was a Baltic aristocrat who had escaped the Russian Revolution.Footnote 1 Between 1933 and 1952, Anrep designed two floor mosaics for the National Gallery. The latest sequence dates from 1952 and is called Modern Virtues. Like Anrep’s earlier work, The Awakening of the Muses of 1928–33 [Fig. 25], it uses recognizable figures from public life, including Virginia Woolf, in place of abstract figures.

Figure 25 Boris von Anrep, Clio, from his National Gallery mosaic (1928–32). ©

Not far from a segment titled Humour, which shows Britannia herself, along with a Union Jack, is a small segment featuring an unknown man with the line ‘Here I lie’ [Fig. 26]. The statement is likely an expression of English humour, linguistic pun in the style of a John Donne or Shakespeare. One of the ways in which the mosaic offers the viewer open ‘lies’ in displaying images of British national identity is the association of each virtue or abstraction with real historical personalities. The poets Anna Akhmatova, with whom Anrep had a love affair before the First World War, and T.S. Eliot are there, alongside the German scientist exiled in the United States, Albert Einstein.

Figure 26 Boris von Anrep, ‘Here I lie’. Fragment from his National Gallery mosaic (1952).

As a group, these people never shared a pint in the same British pub. But as nodes of an imagined network of memory, they were nonetheless very influential. Like Anrep’s mosaics, the creation of trans-imperial memory in interwar Europe was one of the by-products of intellectual exchange in European society of this period. This transnational mosaic of memory was significant not only because of what it contains but also because of what it left out.

Anrep’s mosaic, figures of German, French, and most cultures which are not classical Greece or modern Britain and the United States, are conspicuous by their absence. The only German to be absorbed in British national memory of Europe’s common past was Albert Einstein, then already an American citizen. The place of German culture in this British version of Europe has been visibly called into question, while France and other European countries as well as the United States are altogether absent.